Abstract

First-order radiomic features, such as metabolic tumor volume (MTV) and total lesion glycolysis (TLG), are associated with disease progression in early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). We hypothesized that a model incorporating first- and second-order radiomic features would more accurately predict outcome than MTV or TLG alone. We assessed whether radiomic features extracted from baseline PET scans predicted relapsed or refractory disease status in a cohort of 251 patients with stage I-II HL who were managed at a tertiary cancer center. Models were developed and tested using a machine-learning algorithm. Features extracted from mediastinal sites were highly predictive of primary refractory disease. A model incorporating 5 of the most predictive features had an area under the curve (AUC) of 95.2% and total error rate of 1.8%. By comparison, the AUC was 78% for both MTV and TLG and was 65% for maximum standardize uptake value (SUVmax). Furthermore, among the patients with refractory mediastinal disease, our model distinguished those who were successfully salvaged from those who ultimately died of HL. We conclude that our PET radiomic model may improve upfront stratification of early-stage HL patients with mediastinal disease and thus contribute to risk-adapted, individualized management.

Introduction

In early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), individualized, risk-adapted therapy is desirable to maintain high cure rates while minimizing treatment-related toxicity. For most patients, prognosis is excellent, so de-intensification of therapy is advised to reduce the risk of late treatment-related toxicity1,2. However, a small minority of patients develop relapsed or refractory disease, which may be fatal. Primary refractory disease is associated with particularly poor outcomes3,4. For patients with refractory disease, therapy should not be minimized5. Thus, upfront identification of patients at high risk for refractory disease would be extremely valuable.

The intensity of frontline therapy is dictated by the presence of risk factors at the time of diagnosis. In today’s practice, these risk factors are defined using historic methods. In particular, tumor bulk has long been recognized as an important poor prognostic factor6. Historically, bulk was defined based on the width of the mediastinum on an upright chest x-ray7,8. Subsequently, in the era of computed tomography (CT) scanning, various retrospective studies defined CT criteria for bulky disease, with proposed cut-off values ranging from 5 to 10 cm9–12. Most recently, measurements that reflect both the 3-dimensional disease volume and metabolic activity, such as metabolic tumor volume (MTV) and total lesion glycolysis (TLG), have been associated with patient outcomes in HL13–15. These functional measurements of tumor volume provide additional prognostic information beyond the classical risk factors that include a unidimensional measurement of tumor bulk13. While these metabolic tumor volume metrics may improve risk stratification, further study and validation are needed before they can be incorporated into current daily practice and risk stratification systems.

As a next step, additional data beyond MTV and TLG may be derived from 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Radiomics involves the extraction of a large number of quantitative features from digital images, which can be mined for hypothesis generation16,17. When extracted from PET scans, these features signify aspects of radiotracer intensity (concentration), heterogeneity, and shape within the tumor, reflecting biological characteristics, such as cellular density, proliferation rate, hypoxia, necrosis, and angiogenesis18. “First-order” features are global measurements that do not convey spatial information, such as standardized uptake value (SUV), MTV, and TLG. Second-order features reflect spatial relationships between ≥2 voxels due to variability in the distribution of radiotracer uptake. These data can be derived from gray-level co-occurrence matrices (GLCM). Examples of second-order features include contrast, energy, entropy, and homogeneity19. In multiple other malignancies, first- and second-order features of baseline PET scans have been associated with patient outcomes20–31. Furthermore, textural and shape parameters evaluated on baseline PET scans predicted early metabolic response in a cohort of patients with bulky Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma32. We hypothesized that a model incorporating first- and second-order radiomic features would more accurately predict refractory or relapsed disease status, when compared to MTV, TLG, or maximum SUV (SUVmax) alone, in a cohort of early-stage HL patients.

Materials and Methods

We obtained approval from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board. All work was done in accordance with institutional guidelines and regulations. The status of this study as a HIPAA-compliant, retrospective project waived the prerequisite for informed consent.

Study cohort

Records were reviewed retrospectively for all patients treated at a single tertiary cancer center for classical HL from 2003 through 2013. Inclusion criteria included Ann Arbor stage I or II disease, age of ≥18 years at the time of diagnosis, and availability of an analyzable pre-chemotherapy PET-CT scan. Patients with a disease volume measuring <5 cc were excluded.

PET-CT scans

PET-CT scans were acquired on 1 of 4 scanners: a DST machine, 2 DRX machines, or a DSTE machine (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). The corresponding CT scanners were 8-slice (DST model), 16-slice or 64-slice (DRX model), or 64-slice machines (DSTE model). All PET-CT scanners used the same DISCOVERY platform by General Electric.

Patients fasted for at least 6 hours and were confirmed to have a blood glucose level of <150 mg/dL prior to the FDG injection. An intravenous FDG injection of 555–629 MBq (15–17 mCi) or of 333–407 MBq (9–11 mCi) was administered for 2-dimensional (2D) and 3-dimensional (3D) imaging, respectively, and emission scans were acquired at 3 minutes per field of view. The injection-to-scan time of all patients had a median of 70 minutes (standard deviation 17 minutes). PET images were reconstructed with vendor-provided algorithms. Diagnostic quality CT images were acquired in helical mode with a 3.75-mm slice thickness (pitch of 1.35, rotation speed of 0.5 sec, kVp of 120, and noise index of 30).

All PET-CT scanners at our institution are subject to a rigorous quality assurance/quality control program on a daily, quarterly, and annual basis. Additionally, reconstruction parameters are optimized to ensure harmonization of SUV measurements between scanners. PET data were acquired in 2D mode before January 2008 and in 3D mode after that date. The equivalence between the 2D and 3D reconstruction data have been confirmed using phantom data.

Disease volume definition

PET-CT images were transferred to MIM software (version 6.4.9, MIM Software Inc., Cleveland, OH) and co-registered for further analysis. All sites of nodal disease were contoured manually on the CT scan. Disease was contoured separately by anatomic region, as defined by the Ann Arbor staging method (i.e. mediastinum, left neck, right neck, left axilla, right axilla, etc). Then, an auto-thresholding technique was used to delineate all tumor on the PET scans that was present within the manually contoured volumes and had a body weight SUV ≥2.533.

MTV and TLG were defined using the fixed SUV threshold of 2.5, with all voxels containing SUVs above this cut-off contributing to the MTV. MTV2.5 was calculated in cubic centimeters (cc) by summation of these voxels. For cases in which SUVmax of the primary lesion was lower than that of the threshold, MTV2.5 was considered to be 0. TLG2.5 was computed by multiplying the MTV2.5 by its SUVmean.

Radiomics analysis

Thirty-three quantitative radiomic features, listed in Table 1, were extracted from the MTV2.5 using the in-house imaging software “Imaging Biomarker Explorer” (IBEX)34. This software was designed based on the MATLAB (v8.1.0, MathWorks, Natick, MA) and is available at http://bit.ly/IBEX.MDAnderson. Any disease volume <5 cc was excluded, because quantitative features extracted from small lesions yield less reproducible results than those from larger tumors35. Clean MaskEdge was applied before feature extraction to specify how much of the edge voxel to include in the calculations. IBEX can extract features from discontinuous regions of interest, so all involved nodes within the site of interest were included. Texture features were derived from the GLCM in 2.5D (i.e. first computed on each 2D image and then combined into 2.5D features by averaging of 2D features across the 3D volume).

Table 1.

Radiomic features.

| Category | Features | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity histogram | Global Entropy Global Uniformity |

Global Max Inter quartile Range |

Global Mean Kurtosis |

Global standard deviation Skewness |

| GLCM2.5D* | Auto Correlation Contrast Energy Information Measure 1 Inverse Variance Sum Variance |

Cluster Prominence Correlation Entropy Information Measure 2 Max probability Variance |

Cluster Shade Difference Entropy Homogeneity Inverse Diff. Norm Sum Average |

Cluster Tendency Dissimilarity Homogeneity 2 Inverse Diff. Moment Norm Sum Entropy |

| Shape | Max 3D Diameter | Volume | Roundness | |

*Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix, computed in 2.5D fashion.

Clinical outcomes

The primary clinical outcome was refractory or relapsed disease, with the clinical rationale that patients who suffer refractory or relapsed disease outcomes are at higher risk for mortality, need for salvage chemotherapy, and need for stem cell transplantation3,4,36,37. Primary refractory disease was defined as persistent HL during or within 90 days of completion of upfront therapy (i.e. the final cycle of chemotherapy in patients treated with chemotherapy alone, or the final day of RT in patients treated with combined modality therapy). Relapsed disease was defined as progression more than 3 months after upfront therapy. As a secondary outcome, we assessed death from HL.

Statistical analysis

We aimed to build an imaging biomarker-based model predictive of relapsed or refractory HL. We hypothesized that this model would more accurately predict patient outcomes than MTV, TLG, or SUVmax. Training-validation subsets were used to identify prognostic radiomic features. To investigate the association of primary refractory disease with mediastinal radiomic features specifically, patients with mediastinal involvement (167 patients, 12 refractory cases) were separated randomly into 12 groups, with 1 refractory case per group. Ten training groups established a support vector machine-based AdaBoost iterating algorithm enhanced classifier38, and the remaining 2 groups tested the model.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to test the predictive performance of this model, compared to single variable MTV-, TLG-, and SUVmax-based prediction. Classifier and statistical analyses were built and performed using R3.2.2. The clustering analysis was conducted based on the unsupervised hierarchical clustering via pheatmap R package with default parameters.

Results

The cohort comprised 251 patients with stage I-II HL. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The radiomic features listed in Table 1 were extracted from the baseline PET scans. We assessed for an association of these features with the presence of relapsed or refractory disease.

Table 2.

Patient, treatment, and disease characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total Cohort (n = 251) | Subset with Mediastinal Disease (n = 169) | Subset with Refractory Mediastinal Disease (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 31 years (18–88) | 30 years (18–60) | 29 years (20–57) |

| Female | 144 (57%) | 113 (67%) | 7 (58%) |

| Median Karnofsky performance status at diagnosis (range) | 90% (70–100%) | 90% (70–100%) | 90% (80–100%) |

| Stage I/Stage II | 37 (15%)/214 (85%) | 8 (5%)/161 (95%) | 0 (0%)/12 (100%) |

| B symptoms | 57 (23%) | 40 (24%) | 4 (33%) |

| Bulk (>10 cm) | 76 (30%) | 55 (33%) | 7 (58%) |

| Extranodal disease | 11 (4%) | 6 (4%) | 1 (8%) |

| ABVD or ABVD-like chemotherapy | 246 (98%) | 166 (98%) | 11 (92%) |

| Median number of chemotherapy cycles (range) | 5 (2–6) | 6 (2–6) | 6 (2–6) |

| Consolidative radiation therapy as part of frontline therapy | 175 (70%) | 116 (69%) | 1 (8%) |

| Primary refractory cases | 19 (8%) | 12 (7%) | 12 (100%) |

| Relapsed cases | 9 (4%) | 7 (4%) |

ABVD = doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine.

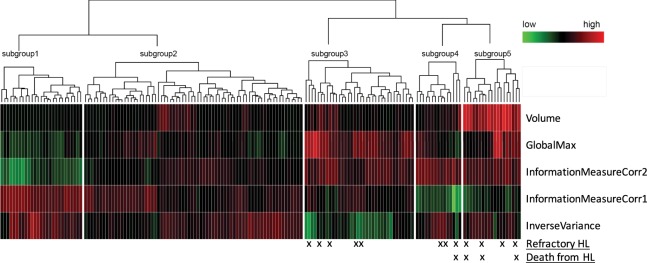

Radiomic features extracted from mediastinal sites on the pre-treatment scans were highly predictive of primary refractory status. Of the 169 patients with mediastinal involvement, 12 had refractory disease. In each case, the primary refractory site included the mediastinum; in 2 patients, refractory disease was present within the neck, as well. When considering mediastinal sites only (n = 169), the baseline radiomic features that were most predictive of primary refractory disease included the first-order features GlobalMax (i.e. SUVmax) and Volume, and the second-order features InformationMeasureCorr1, InformationMeasureCorr2, and InverseVariance derived from the GLCM2.5. Background information regarding these features is summarized in Table 3. These 5 features were included in a model that predicted the risk of primary refractory HL with an area under the curve (AUC) of 95.2% (95% CI: 87.0–100.0%) and total error rate of 1.8%. By comparison, the AUC was 78% (95% CI: 66.6–90.3%) for both MTV and TLG and was 65% (95% CI: 48.1–83.4%) for SUVmax alone (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

PET radiomic features that were most predictive of refractory mediastinal disease.

| Feature | Definition | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity Global Max | The intensity maximum among all the voxels (SUVmax). | 53 | |

| Volume | The physical volume. For positron emission tomography, volume is equivalent to the metabolically active tumor volume (MTV). | 54 | |

| Inverse variance | Random variables are aggregated to minimize the variance of the weighted average where each random variable is weighted in inverse proportion to its variance. | 42 | |

| InformationMeasureCorr1* | First measure of information theoretic correlation, where HXY is the entropy for joint probability. | 55 | |

| InformationMeasureCorr2* | Second measure of information theoretic correlation, a grey level co-occurrence textural feature. | 55 |

*Information theoretic correlation is a grey level co-occurrence textural feature and an index of tumor heterogeneity. It is estimated using 2 different measures that incorporate entropy chiefly in the computation process56.

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Curves for the model incorporating 5 radiomic features (red), metabolic tumor volume (blue), total lesion glycolysis (black), and GlobalMax (SUVmax, green) in the subset of patients with mediastinal disease.

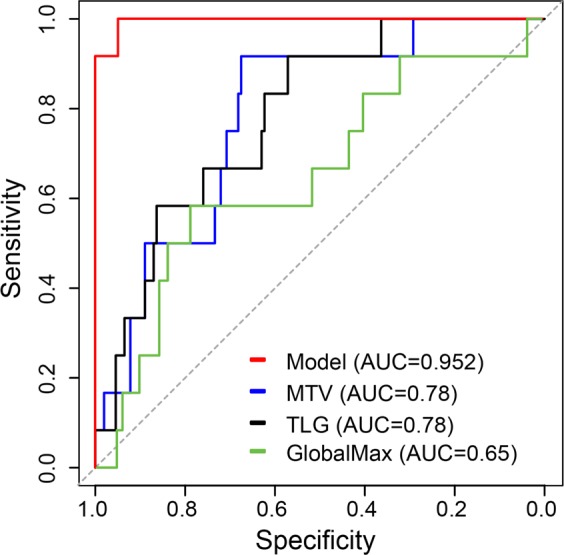

Based on these 5 features, the expression profiles were subject to unsupervised hierarchical clustering, and the patients were divided into 5 subgroups (Fig. 2 and Table 4). No patient in Group 1 (n = 27) or 2 (n = 72) had primary refractory disease. The other 3 groups included all 12 patients with refractory disease. Furthermore, these groups distinguished patients with highly refractory disease who died of HL from those with initially refractory disease who were salvaged successfully. Group 3 (n = 36) included 5 patients (14%) with refractory disease, none of whom died of HL; Group 4 (n = 15) included 3 patients (20%) with refractory disease, 1 (33%) of whom died of HL; and Group 5 (n = 19) included 4 patients (21%) with refractory disease, 3 (75%) of whom died of HL (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Heatmap demonstrating the prognostic subgroups based on the 5 most predictive mediastinal radiomic features.

Table 4.

Prognostic groups based on radiomic feature analysis.

| Group | n | Refractory Cases (n = 12) | Deaths from Refractory HL (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 72 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 36 | 5 (14%) | 0 |

| 4 | 15 | 3 (20%) | 1 (33%) |

| 5 | 19 | 4 (21%) | 3 (75%) |

In contrast, features extracted from the total disease volume, inclusive of all anatomic sites, did not predict the risk of refractory disease (49.5% error rate). Additionally, radiomic features did not predict the risk of relapsed disease (51% error rate for the largest volume and 49% for the highest SUV volume).

Conclusion

We have identified a model for imaging biomarker-based risk stratification in early-stage HL patients with mediastinal disease. Our model incorporated 5 of the most highly predictive PET radiomic features. Two of these features, GlobalMax (SUVmax) and Volume (MTV) are known prognostic markers in HL13–15. With the addition of 3 other features, all measures of texture, our model more accurately predicted the risk of primary refractory disease than MTV, TLG, or SUVmax. This model not only identified the risk of primary refractory disease, but also distinguished a high-risk refractory subgroup that could not be salvaged. Thus, advanced imaging biomarkers may identify patients who would benefit from escalation vs. de-intensification of therapy. Such individualization of treatment could improve the therapeutic ratio, contributing to superior patient outcomes.

The management of early-stage HL patients is guided by the presence of known clinical and radiographic risk factors5. The radiographic finding included in current risk stratification schemas is tumor bulk. The definition of bulk varies among investigators and is typically defined by a single measurement of tumor diameter8,39–41. However, such unidimensional measurements do not fully represent disease burden. Several groups have shown that 3-dimensional assessments of disease volume, such as MTV, enable superior prediction of clinical outcomes when compared to standard risk factors, including unidimensional measurements of tumor bulk13–15. As the next step, our findings suggest that additional PET radiomic features may enhance the predictive capability of MTV. Consistent with our findings, Bouallègue et al. published a report of 57 patients with bulky lymphoma (14 HL and 43 non-Hodgkin lymphoma). In this cohort, a model incorporating baseline PET textural and shape parameters more accurately predicted disease response on interim PET scans than other factors, including MTV and histology32.

This work adds to a growing body of literature demonstrating an association between radiomic features and clinical outcome. Advanced radiomic features have been shown to predict treatment response in multiple other malignancies, such as sarcoma, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, head-and-neck cancer, esophageal cancer, and cervical cancer22–31,42,43. In other malignancies, some of the optimal models have incorporated both PET and CT features25 or pre- and post-therapy imaging findings28, suggesting possible future directions for our work.

In this analysis, we found that baseline PET radiomic features predicted the risk of refractory disease, but, in contrast, did not predict for relapsed disease. This distinction may reflect underlying biological differences in the pathways toward relapsed versus refractory disease, and further, could have clinical implications. In contrast with refractory disease, relapsed disease occurs later in follow-up, after a disease-free interval. With a longer latency before disease failure, it is possible that early data from the initial PET is less predictive of the relapse outcome. Future studies exploring associations between radiomic biomarkers and relapse may benefit from analyses of interim or post-treatment imaging results. Clinical data also suggest that relapsed and refractory disease may be distinct processes. For example, the long-term survival for patients with relapsed disease tends to be more favorable. It ranged from 27% to 83% in the German Hodgkin Study Group trials, depending on clinical risk factors36,37. In contrast, for patients with refractory disease, long-term survival ranges between 8% and 50%3,4. Therefore, the imaging biomarker features on initial staging PET scans may provide an early clue as to fundamentally differing biological behaviors of relapsed versus refractory disease and response to current systemic agents.

The optimal method for tumor volume segmentation is debated. We used a fixed threshold for tumor delineation. This method yields reproducible volumes; however, a disadvantage of the fixed threshold approach is that tumor with low FDG-uptake is excluded, which may bias heterogeneity assessments. Additionally, this approach does not take background uptake into consideration44. In future work, segmentation methods may be compared to identify the preferred approach in this patient population.

Our hypothesis-generating study is not without limitations. For example, PET technology evolved over the course of the study period, so some scans were obtained in 2D mode and others in 3D mode. Significant care was taken to minimize differences between scans obtained in 2D versus 3D mode; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that PET acquisition mode influenced the radiomic features and, thus, affected our findings.

A second critical limitation is that our findings are based on a single institutional dataset with a small number of events and have not been validated using an external cohort. Radiomic features may be influenced by PET acquisition and reconstruction parameters45–48. Therefore, models based on data from one scanner or institution may not be directly applicable to data from another scanner or institution. Methods to standardize PET scanning have been proposed49,50; nonetheless, variability across institutions exists. External validation of our model is an important next step. Its robustness and reproducibility must be confirmed, before it can be applied in clinical practice. One PET acquisition factor that warrants particular attention in mediastinal lymphoma texture feature analysis is respiratory motion, which may result in blurring across the tumor volume51,52.

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between advanced PET radiomic features and refractory disease status in early-stage HL patients. We suggest that our model be tested in future studies. We used an open-source platform for feature extraction, so researchers at other institutions can explore our findings. Development and validation of an imaging biomarker-based prognostic schema could aid a risk-adapted, individualized therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Center for Radiation Oncology Research at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Dr. Smith receives research effort support from NIH/NCI (K07 CA211804). In addition, this research is supported by the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation; Dr. Fuller is a Sabin Family Foundation Fellow. Dr. Fuller receives funding and effort support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including: the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research Award (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248-01); a National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Mathematical Sciences, Joint NIH/NSF Initiative on Quantitative Approaches to Biomedical Big Data (QuBBD) Grant (NSF 1557679); the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Early Stage Development of Technologies in Biomedical Computing, Informatics, and Big Data Science Award (1R01CA214825-01); NCI Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148-01); an NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Pilot Research Program Award from the UT MD Anderson CCSG Radiation Oncology and Cancer Imaging Program (P30CA016672); NIH/NCI Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Developmental Research Program Award (P50 CA097007-10); and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) Research Education Program for Residents and Clinical Fellows (R25EB025787).

Author Contributions

S.A.M. and H.E. wrote the manuscript. J.L. performed radiomic analyses. Q.W. performed statistical analyses. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sarah A. Milgrom and Hesham Elhalawani contributed equally.

References

- 1.Engert A, et al. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:640–652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eich HT, et al. Intensified chemotherapy and dose-reduced involved-field radiotherapy in patients with early unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD11 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4199–4206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonfante V, et al. Outcome of patients with Hodgkin’s disease failing after primary MOPP-ABVD. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:528–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moskowitz CH, et al. Effectiveness of high dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with biopsy-proven primary refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:645–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2003.04828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen PB, Gordon LI. Frontline Therapy for Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma by Stage and Prognostic Factors. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2017;11:1179554917731072. doi: 10.1177/1179554917731072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mauch P, Goodman R, Hellman S. The significance of mediastinal involvement in early stage Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1978;42:1039–1045. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197809)42:3<1039::AID-CNCR2820420302>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duhmke E, et al. Low-dose radiation is sufficient for the noninvolved extended-field treatment in favorable early-stage Hodgkin’s disease: long-term results of a randomized trial of radiotherapy alone. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2905–2914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eghbali, H., Raemaekers, J., Carde, P. & Group, E. L. The EORTC strategy in the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur J Haematol Suppl, 135–140 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Mendenhall NP, Cantor AB, Barre DM, Lynch JW, Jr, Million RR. The role of prognostic factors in treatment selection for early-stage Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Clin Oncol. 1994;17:189–195. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North LB, et al. Importance of initial mediastinal adenopathy in Hodgkin disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138:229–235. doi: 10.2214/ajr.138.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley AJ, Carrington BM, Lawrance JA, Ryder WD, Radford JA. Assessment and significance of mediastinal bulk in Hodgkin’s disease: comparison between computed tomography and chest radiography. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, et al. Definition of bulky disease in early stage Hodgkin lymphoma in computed tomography era: prognostic significance of measurements in the coronal and transverse planes. Haematologica. 2016;101:1237–1243. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.141846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhtari, M. et al. Re-classifying patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma based on functional radiographic markers at presentation. Blood, 10.1182/blood-2017-04-773838 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Song MK, et al. Metabolic tumor volume by positron emission tomography/computed tomography as a clinical parameter to determine therapeutic modality for early stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1656–1661. doi: 10.1111/cas.12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanoun S, et al. Baseline metabolic tumour volume is an independent prognostic factor in Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1735–1743. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2783-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016;278:563–577. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambin P, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:749–762. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook GJR, et al. Radiomics in PET: principles and applications. Clinical and Translational Imaging. 2014;2:269–276. doi: 10.1007/s40336-014-0064-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook, G. J. R., Azad, G., Owczarczyk, K., Siddique, M. & Goh, V. Challenges and Promises of PET Radiomics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.12.268 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Eary JF, O’Sullivan F, O’Sullivan J, Conrad EU. Spatial heterogeneity in sarcoma 18F-FDG uptake as a predictor of patient outcome. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1973–1979. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha S, Park S, Bang JI, Kim EK, Lee HY. Metabolic Radiomics for Pretreatment (18)F-FDG PET/CT to Characterize Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Histopathologic Characteristics, Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, and Prognosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1556. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01524-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tixier F, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity characterized by textural features on baseline 18F-FDG PET images predicts response to concomitant radiochemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:369–378. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook GJ, et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Erlotinib: Heterogeneity of (18)F-FDG Uptake at PET-Association with Treatment Response and Prognosis. Radiology. 2015;276:883–893. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook GJ, et al. Are pretreatment 18F-FDG PET tumor textural features in non-small cell lung cancer associated with response and survival after chemoradiotherapy? J Nucl Med. 2013;54:19–26. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaidya M, et al. Combined PET/CT image characteristics for radiotherapy tumor response in lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2012;102:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda K, et al. Clinical utility of texture analysis of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with Stage I lung cancer treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. J Radiat Res. 2017;58:862–869. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrx050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovinfosse P, et al. FDG PET/CT texture analysis for predicting the outcome of lung cancer treated by stereotactic body radiation therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1453–1460. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan S, et al. Predicting pathologic tumor response to chemoradiotherapy with histogram distances characterizing longitudinal changes in 18F-FDG uptake patterns. Med Phys. 2013;40:101707. doi: 10.1118/1.4820445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, et al. Modeling pathologic response of esophageal cancer to chemoradiation therapy using spatial-temporal 18F-FDG PET features, clinical parameters, and demographics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beukinga RJ, et al. Predicting Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Esophageal Cancer with Textural Features Derived from Pretreatment (18)F-FDG PET/CT Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:723–729. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.180299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucia, F. et al. Prediction of outcome using pretreatment (18)F-FDG PET/CT and MRI radiomics in locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 10.1007/s00259-017-3898-7 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ben Bouallegue F, et al. Association between textural and morphological tumor indices on baseline PET-CT and early metabolic response on interim PET-CT in bulky malignant lymphomas. Med Phys. 2017;44:4608–4619. doi: 10.1002/mp.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freudenberg LS, et al. FDG-PET/CT in re-staging of patients with lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:325–329. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L, et al. IBEX: an open infrastructure software platform to facilitate collaborative work in radiomics. Med Phys. 2015;42:1341–1353. doi: 10.1118/1.4908210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fried DV, et al. Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Prognostic Value of FDG PET Quantitative Imaging Features Combined with Clinical Prognostic Factors. Radiology. 2016;278:214–222. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sieniawski M, et al. Outcome of patients experiencing progression or relapse after primary treatment with two cycles of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for early-stage favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2000–2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boll B, et al. Relapsed hodgkin lymphoma in older patients: a comprehensive analysis from the German hodgkin study group. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4431–4437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.https://www.mathworks.com/discovery/adaboost.html.

- 39.Engert A, et al. Involved-field radiotherapy is equally effective and less toxic compared with extended-field radiotherapy after four cycles of chemotherapy in patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the HD8 trial of the German Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3601–3608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer RM, et al. Randomized comparison of ABVD chemotherapy with a strategy that includes radiation therapy in patients with limited-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4634–4642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoppe RT, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma, version 2.2012 featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:589–597. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aerts HJ, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Oikonomou A, Wong A, Haider MA, Khalvati F. Radiomics-based Prognosis Analysis for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46349. doi: 10.1038/srep46349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostakoglu L, Chauvie S. Metabolic Tumor Volume Metrics in Lymphoma. Semin Nucl Med. 2018;48:50–66. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galavis PE, Hollensen C, Jallow N, Paliwal B, Jeraj R. Variability of textural features in FDG PET images due to different acquisition modes and reconstruction parameters. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:1012–1016. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.498437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lovat E, et al. The effect of post-injection (18)F-FDG PET scanning time on texture analysis of peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis-1. EJNMMI Res. 2017;7:35. doi: 10.1186/s13550-017-0282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leijenaar RT, et al. The effect of SUV discretization in quantitative FDG-PET Radiomics: the need for standardized methodology in tumor texture analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11075. doi: 10.1038/srep11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doumou G, Siddique M, Tsoumpas C, Goh V, Cook GJ. The precision of textural analysis in (18)F-FDG-PET scans of oesophageal cancer. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2805–2812. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3681-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shankar LK, et al. Consensus recommendations for the use of 18F-FDG PET as an indicator of therapeutic response in patients in National Cancer Institute Trials. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1059–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boellaard R, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:328–354. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yip S, et al. Comparison of texture features derived from static and respiratory-gated PET images in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliver JA, et al. Variability of Image Features Computed from Conventional and Respiratory-Gated PET/CT Images of Lung Cancer. Transl Oncol. 2015;8:524–534. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haralick, R. M. & Shapiro, L. G. Computer and Robot Vision. (Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., 1992).

- 54.Legland, D., Kiêu, K. & Devaux, M.-F. Computation Of Minkowski Measures On 2d And 3d Binary Images. 2011 26, 10, 10.5566/ias.v26.p83-92 (2011).

- 55.Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. 1973;SMC-3:610–621. doi: 10.1109/TSMC.1973.4309314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zwanenburg, A. L. S. & Vallieres, M. Image biomarker standardisation initiative, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1612.07003.pdf. Last accessed 12/7/2018 (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.