Abstract

Axially chiral arylpyrroles are key components of pharmaceuticals and natural products as well as chiral catalysts and ligands for asymmetric transformations. However, the catalytic enantioselective construction of optically active arylpyrroles remains a formidable challenge. Here we disclose a highly efficient strategy to access enantioenriched axially chiral arylpyrroles by means of organocatalytic atroposelective desymmetrization and kinetic resolution. Depending on the remote control of chiral catalyst, the arylpyrroles were obtained in high yields and excellent enantioselectivities under mild reaction conditions. This strategy tolerates a wide range of functional groups, providing a facile avenue to approach axially chiral arylpyrroles from simple and readily available starting materials. Selected arylpyrrole products proved to be efficient chiral ligands in asymmetric catalysis and also important precursors for further synthetic transformations into highly functionalized pyrroles with potential bioactivity, especially the axially chiral fully substituted arylpyrroles.

Subject terms: Asymmetric catalysis, Homogeneous catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Axially chiral arylpyrroles are structural motifs often found in natural and medicinal products. Here, the authors report the atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral arylpyrrole derivatives, which proved to be efficient chiral ligands for asymmetric catalysis, through desymmetrization and kinetic resolution.

Introduction

Axially chiral arylpyrroles constitute the core skeletons of a wide range of natural products1–3 and pharmaceutical agents4–6. Owing to their intrinsic structure characteristics, they proved to possess widespread applications in organic synthesis7–15. For example, arylpyrroles scaffolds occur in plenty of chiral phosphine ligands applied in numerous transition metal-mediated reactions (Fig. 1)7–9. More importantly, the optically pure arylpyrrole derivatives have been extensively used in current asymmetric reactions10–14 as chiral resolving agents10,11, chiral ligands12,13 as well as chiral catalysts14. Nonetheless, over the past decade, conventional approaches to access these optically active arylpyrroles were by optical resolution of the racemates using chiral resolution agents or chiral column chromatography, which not only required the stoichiometric amounts of chiral reagent, but also were limited by the substrate scope10,15,16. While the first catalytic asymmetric Paal–Knorr reaction was established to access highly enantioenriched axially chiral arylpyrroles by our group recently17, complicated catalytic system and narrow substrate range restricted its application. Therefore, the atroposelective construction of axially chiral arylpyrroles remains comparatively unexplored and the development of facile and direct route is highly appealing.

Fig. 1.

Representative molecules containing axially chiral arylpyrrole frameworks. a Bioactive natural products. b Resolving agent. c Chiral ligands and catalysts

Recently, Bencivenni’s group reported a pioneering study on the remote control of the axial chirality of atropisomeric succinimides through vinylogous Michael addition reaction via aminocatalytic desymmetrization of arylmaleimides (Fig. 2a)18–20. The key feature of this method relies on the recognition of the catalyst with regards to the maleimide’s symmetry plane. The hydrogen bonding between the oxygen of the carbonyl group of the substrate and the protonated quinuclidine moiety of the catalyst is crucial for the excellent stereoselectivity. Inspired by this elegant work involving the remote control of the axial chirality, as well as our ongoing interest in chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) catalytic atroposelective synthesis of enantioenriched axially chiral structures21,22, we envisage that the readily available 2,5-disubstituted arylpyrroles should be suitable prochiral substrates to afford the expected axially chiral structures by enantioselective desymmetrization23–26 or kinetic resolution27–32 under the strategy of remote stereocontrol by organocatalysts (Fig. 2b)33–36. However, the major challenges in this scenario would be: (1) the choice of appropriate electrophilic reagents could react efficiently with the arylpyrroles. Meanwhile, the electrophiles would interact with the organocatalyst in a reasonable spatial configuration to enhance the reactivity and offer an ideal chiral environment for the control of the atroposelectivity; (2) the careful selection of compatible chiral organocatalyst to effectively induce the axial chirality since the distance between the chiral axis and the catalyst activation site is relatively long; (3) lacking an available proton donor group on the arylpyrroles for hydrogen bonding effect, the interaction between arylpyrrole substrates and the chiral catalyst could not occur effectively37–44. Herein, we present our strategy to overcome the abovementioned challenges and successfully construct the highly enantioenriched axially chiral arylpyrroles by means of the remote control of the axial chirality. Two complementary approaches, namely desymmetrization/kinetic resolution, are devised with CPA as the catalyst to give the axially chiral arylpyrroles with highly structural diversity and excellent enantiocontrol. These optical active axially chiral arylpyrroles are able to sever as chiral building blocks for rapid transformations to functionalized pyrroles with potential bioactivity and ligands for asymmetric catalytic reactions.

Fig. 2.

Background and project synopsis. a Aminocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of atropisomeric succinimides via remote control strategy (Bencivenni’s work). b Our strategy for the remote enantiocontrol of axially chiral arylpyrroles. Black circle, sterically bulky substituent

Results

Reaction condition optimization

To validate the feasibility of the hypothesis, the reaction of 1-(2-(tert-butyl)phenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole 1a and diethyl ketomalonate 2a were conducted with 10 mol% SPINOL-derived CPA (S)-C1 in toluene at room temperature. Encouragingly, the reaction proceeded smoothly to give the desired axially chiral arylpyrrole 3a in 74% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Despite only 22% ee, this result clearly demonstrated that the organocatalytic remote control of the chiral axis of arylpyrroles by desymmetrization strategy was feasible. To improve reaction outcomes, we turned our attention to explore the effect of the catalysts. As shown in Table 1, all the tested CPAs were capable of catalyzing this reaction to give 3a in reasonable to excellent yields (Table 1, entries 2–8). These results also evidenced that CPAs containing bulky substituents could significantly enhance the stereocontrol of the reaction and H8-BINOL-derived (S)-C8 with 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl group on the 3,3′-position was superior to other catalysts to give the desired product 3a in 93% yield with 90% ee. After that, various solvents were evaluated to prove the cyclohexane as the optimal reaction solvent (Table 1, entries 8–12). Lower reaction temperature resulted in negligible effect in enantioselectivity, accompanied by the loss of chemical yield (Table 1, entry 13). Further optimization revealed that 5 mol% catalyst loading could uphold the enantioselectivity effectively with slight increase of chemical yield when the reaction time was extended to 36 h (Table 1, entries 14 and 15). Based on the above results (See Supplementary Tables 1–4), the optimized conditions were concluded as follows: treatment of 2a with 1.5 equivalent of 1a in cyclohexane at room temperature in the presence of 5 mol% of (S)-C8 and the reaction could give the desired axially chiral arylpyrrole 3a in 96% isolated yield with 95% ee (Table 1, entry 15).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | T (°C) | yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

| 1 | (S)-C1 | toluene | rt | 74 | −22 |

| 2 | (S)-C2 | toluene | rt | 85 | −42 |

| 3 | (S)-C3 | toluene | rt | 38 | −47 |

| 4 | (S)-C4 | toluene | rt | 43 | −71 |

| 5 | (S)-C5 | toluene | rt | 59 | −72 |

| 6 | (S)-C6 | toluene | rt | 75 | −86 |

| 7 | (R)-C7 | toluene | rt | 91 | −89 |

| 8 | (S)-C8 | toluene | rt | 93 | 90 |

| 9 | (S)-C8 | CH2Cl2 | rt | 91 | 77 |

| 10 | (S)-C8 | EtOAc | rt | 60 | 86 |

| 11 | (S)-C8 | CH3CN | rt | 92 | 62 |

| 12 | (S)-C8 | c-hexane | rt | 92 | 96 |

| 13 | (S)-C8 | c-hexane | 10 | 45 | 97 |

| 14d | (S)-C8 | c-hexane | rt | 83 | 95 |

| 15d,e | (S)-C8 | c-hexane | rt | 96 | 95 |

aUnless otherwise stated, all reactions were carried out with 1a (0.15 mmol), 2a (0.10 mmol), CPA (10 mol%) in 1.5 mL solvent at room temperature for 24 h

bIsolated yield

cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis

d(S)-C8 (5 mol%) was used

eReaction was allowed to stir at room temperature for 36 h

Substrate scope

After establishing the optimal reaction conditions, we set out to explore the substrate generality of this transformation. Firstly, the substrate scope with respect to the symmetrical arylpyrroles was investigated (1a–1r). Most reactions could be completed within 64 h to give the desired axially chiral arylpyrroles (Table 2, 3a–3r) in high yields (82–99%) with excellent enantioselectivities (83–97% ee). It is noteworthy to point out that the ortho group on the phenyl ring is not only restricted to tbutyl group, iodo, isopropyl, trifluoromethyl, diphenyl phosphine, 2-isopropenyl, styrene as well as cyclohexene groups were also applicable to give the expected products with good to excellent enantiocontrol (3g–3q). Subsequently, symmetrical arylpyrroles 1r bearing diethyl group could afford 3r in excellent yield and good enantioselectivity. Moreover, varying the ester moiety of ketomalonate could also result in excellent enantioselectivities (3s–3u). Notably, 1o with a diphenyl phosphine substituent was converted to the corresponding product 3o and 3u as potential chiral phosphine ligands. Besides, the halide substituents in the obtained arylpyrroles provided opportunities for the downstream coupling reactions to set up a compound library by routine transition metal-catalyzed reactions. Furthermore, the absolute configurations of the axially chiral products were assigned to be (aR) by X-ray crystallographic analysis of 3s and those of the other products were assigned by analogy (see Supplementary Figure 1). To verify the practicality of such method, a gram-scale reaction was carried out for the synthesis of 3a under the optimal reaction conditions. As displayed in Table 2, no significant variation was detected in terms of the chemical yield and stereoselectivity as compared to the small scale reaction.

Table 2.

Substrate scope with respect to symmetric prochiral arylpyrroles.a

|

aUnless otherwise stated, all reactions were carried out with 1 (0.30 mmol), 2 (0.20 mmol), (S)-C8 (5 mol%) in 3.0 mL c-hexane at room temperature

bGram-scale reactions with 1a (8.7 mmol) and 2a (5.8 mmol)

cConducted with 1 (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.60 mmol), (S)-C8 (10 mol%) in c-hexane/methylcyclohexane (1.5 mL/1.5 mL) at −30 °C

d1 (0.24 mmol) was used

eConducted at 30 °C

fConducted at 50 °C. Styryl, phenyl vinyl

Encouraged by the above results about the construction of axially chiral arylpyrroles via atroposelective desymmetrization of symmetric substrates, we continued to explore the feasibility of this reaction with asymmetric racemic arylpyrroles by using kinetic resolution to further expand the substrate scope. Plenty of asymmetric arylpyrrole racemates with aromatic substituents on the pyrrole ring were then prepared and subjected to the standard conditions. The results were summarized in Table 3 and all the reactions underwent smoothly to give good to high selectivity factor (S = 32–69, 5a–5l). The corresponding products were obtained in 87–94% ee with 42–47% isolated yields regardless of the steric and electronic properties of the substituents. Notably, substrates possessing a naphthyl or thienyl group (5j–5l) also worked efficiently to afford high selectivity, respectively. Moreover, replacement of aromatic substitutions with alkyl group gave rise to unobvious effect on the reaction outcomes (5m–5n). Our method thus represents one of the most straightforward syntheses of axially chiral arylpyrrole and its analogs. The absolute configuration of 5a was attributed to be (aS) by X-ray crystallographic analysis and those of the other products were assigned by analogy (see Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 3.

Substrate scope with respect to asymmetric racemic arylpyrroles.a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | t (d) | Yield of 4 (%)b | ee of 4 (%)c | Yield of 5 (%)b | ee of 5 (%)c | Conv. (%) | S d |

| 1 | 4.0 | 52 (4a) | 72 | 43 (5a) | 91 | 44 | 46 |

| 2 | 3.0 | 51 (4b) | 80 | 45 (5b) | 89 | 47 | 42 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 52 (4c) | 76 | 44 (5c) | 90 | 46 | 44 |

| 4 | 4.0 | 49 (4d) | 89 | 46 (5d) | 91 | 49 | 63 |

| 5 | 3.5 | 51 (4e) | 73 | 44 (5e) | 91 | 45 | 46 |

| 6 | 3.5 | 52 (4f) | 76 | 45 (5f) | 88 | 46 | 36 |

| 7 | 6.0 | 50 (4g) | 77 | 45 (5g) | 92 | 46 | 56 |

| 8 | 3.5 | 48 (4h) | 81 | 47 (5h) | 89 | 48 | 43 |

| 9 | 3.5 | 52 (4i) | 72 | 43 (5i) | 90 | 44 | 41 |

| 10 | 3.5 | 51 (4j) | 81 | 46 (5j) | 91 | 47 | 53 |

| 11 | 3.5 | 51 (4k) | 75 | 45 (5k) | 87 | 46 | 32 |

| 12 | 4.0 | 54 (4l) | 71 | 42 (5l) | 94 | 43 | 69 |

| 13 | 3.5 | 50 (4m) | 82 | 45 (5m) | 91 | 47 | 54 |

| 14 | 3.5 | 46 (4n) | 85 | 47 (5n) | 90 | 49 | 51 |

aAll reactions were carried out with (rac)-4 (0.40 mmol), 2a (0.20 mmol), (S)-C8 (10 mol%) in cyclohexane (4.8 mL) at 30 °C

bIsolated yield

cDetermined by chiral stationary phase HPLC analysis

dThe selectivity factor was calculated as S = ln[(1 − C)(1 − ee(4))]/ln[(1 − C)(1 + ee(4))], C = ee(4)/(ee(5) + ee(4))

Versatile synthetic transformations

To demonstrate the synthetic utility of the obtained axially chiral arylpyrroles, a series of chemical transformations were then conducted (Fig. 3a). Firstly, the free OH group of the axially chiral arylpyrrole 3a could be easily protected by a benzyl group to yield compound 6. Next, the treatment of compound 3a with thiourea or methylamine gave the corresponding diamide 7 or thiobarbituric structure 8 in almost quantitative yield without any erosion of enantioselectivity45,46. While highly functionalized pyrroles show a wide spectrum of bioactivities, very few methods are available to access these frameworks47, particularly penta-substituted axially chiral arylpyrroles. Gratifying, the fully substituted axially chiral pyrroles 9, 10, 11, and 12 could be generated from 3a by classic Mannich and Vilsmeier–Haack reaction, respectively in moderate yields with highly preserved chiral integrity48. Subsequently, bromination of 3a with NBS gave axially chiral arylpyrrole 13 in 80% yield, which could be employed as a precursor to prepare fully substituted axially chiral pyrroles by the following coupling reactions. Furthermore, the treatment of 3a with 4-methyl-benzenesulfonylisocyanate provided compound 14 without loss of stereochemical integrity. Noteworthy, arylpyrrole (R)-3a could be readily oxidized to dialdehyde 15 with cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate as the oxidative reagent49. Moreover, the obtained product 3h possessing an iodo substituent was an applicable reactant for classic transition metal-mediated coupling reactions (Fig. 3b). For instance, the Sonogashira reaction proceeded smoothly to furnish the desired product 16 with a synthetic useful alkynyl group in 82% yield, while compound 17 was produced efficiently by Suzuki coupling with organoboronic acid in the presence of palladium catalyst. Apart from that, the verified axially chiral phosphine ligand 3o could also be synthesized from 3h via rapid C–P bond formation in 66% yield. Notably, no ee erosion was detected for all these reactions.

Fig. 3.

Versatile synthetic transformations. a Synthetic transformations of compound 3a. Ts, p-toluenesulfonyl. b Synthetic transformations of compound 3h

Configurational stability test and catalytic applications

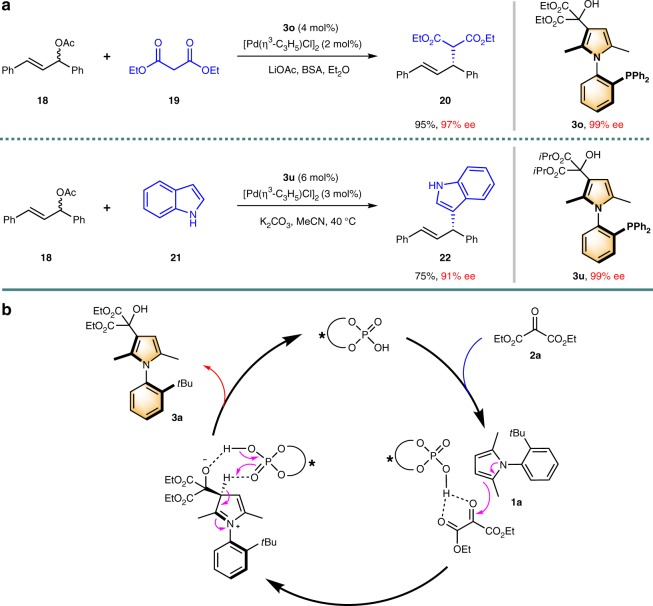

The investigation for the configurational stability of the product was conducted by heating a solution of 3a in different solvent (iPrOH, DCE, and toluene) at up to 150 °C for 24 h. Deteriorations of stereochemical integrity were negligible even under the conditions which the substrate began to decompose. Similar experimental results were obtained with 3o and 5c as the test objects (see Supplementary Table S6–S8). Therefore, this kind of axially chiral compounds displayed a high-rotation energy and may have potential applications as organocatalysts/ligands. Finally, we evaluated the applicability of the resulted axially chiral arylpyrrole in asymmetric catalysis. Compound 3o (99% ee, after semipreparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) enantioseparation) was then selected as the ligand for the palladium catalyzed allylic alkylation50. Gratifyingly, the reaction of racemic 18 and malonate 19 proceeded effectively with 2 mol% of palladium catalyst and 4 mol% of 3o to give the desired product 20 in 95% yield with 97% ee. Aside from 3o, compound 3u (99% ee, recrystallization with Et2O/hexane) could also work well in this type of reaction with indole as the nucleophile, indicating that the resulted highly enantioenriched axially chiral arylpyrrole is capable of inducing the chirality in asymmetric synthesis (Fig. 4a). Further studies with regard to the application of axially chiral arylpyrroles as catalysts or ligands for asymmetric reactions are currently under active investigations.

Fig. 4.

Applications in asymmetric catalysis and plausible mechanism. a Asymmetric catalysis applications. b Proposed reaction mechanism

Plausible mechanism

A monofunctional activation mode was proposed in Fig. 4b for this asymmetric transformation based on the experimental results and the reports from Terada51 and Rueping52. The hydrogen bonding between ketomalonate and CPA was the pivotal interaction to form the chiral pocket37 for the induction of chirality. The second carbonyl of the ketomalonate is essential to fix the whole system in a rigid configuration. Besides, such a pathway basically coincides with the plausible mechanism provided by List and Liu et al. for the addition of indolizines and N-methylpyrroles to enones and imines38–40.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a highly efficient and practical approach for the atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral arylpyrrole derivatives through two complementary asymmetric transformations (desymmetrization/kinetic resolution). Excellent yields and enantioselectivities were obtained with CPA as the chiral catalyst. The key feature of this approach is the achievement of axial chirality via remote control manner, allowing the chiral catalyst to transfer its stereochemical properties along the C–N axis of arylpyrrole. Moreover, highly enantioenriched arylpyrroles proved to be efficient chiral ligands in asymmetric catalysis and versatile building blocks to access other useful axially chiral molecules. Diversified synthetic transformations demonstrated the utilities of this approach, yielding a variety of functionalized axially chiral arylpyrroles, especially the axially chiral penta-substituted arylpyrroles.

Methods

General information

Chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. CPA was purchased from Daicel Chiral Technologies (China). Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated silica gel 60 GF254 plates. Flash column chromatography was performed using Tsingdao silica gel (60, particle size 0.040–0.063 mm). Visualization on TLC was achieved by use of UV light (254 nm) or iodine. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker DPX 400 spectrometer at 400/500 MHz for 1H NMR, 100/125 MHz for 13C NMR and 376 MHz for 19F NMR in CDCl3, DMSO-d6 with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard. The chemical shifts are expressed in ppm and coupling constants are given in Hz. Data for 1H NMR are recorded as follows: chemical shift (δ, ppm), multiplicity (s = singlet; d = doublet; t = triplet; q = quartet; p = pentet; m = multiplet; br = broad), coupling constant (Hz), integration. Data for 13C NMR are reported in terms of chemical shift (δ, ppm). Mass spectrometric data were obtained using Bruker Apex IV RTMS. The enantiomeric excess values were determined by chiral HPLC with an Agilent 1200 LC instrument and CHIRALPAK and CHIRALCEL columns. High resolution mass spectroscopy analyses were performed at a Bruker Daltonics. Inc mass instrument (electrospray ionization (ESI)), Thermo Scientific. Q-Exactive (heated ESI (HESI)), and Thermo Scientific. Orbitrap Fusion (HESI).

General procedure for the synthesis of racemic 3

An oven-dried 10 mL of Schlenk tube was charged with arylpyrroles 1 (0.15 mmol), 1 mL of CH2Cl2 and diphenyl phosphate (0.01 mmol) at ambient temperature. Then, ketomalonate 2 (0.10 mmol) was added to the above solution and the mixture was stirred until the starting material was completely consumed. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash column chromatography (ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to afford the corresponding racemic product 3.

General procedure for the synthesis of (R)-3

An oven-dried 10 mL of Schlenk tube was charged with arylpyrroles 1 (0.30 mmol), (S)-C8 (0.01 mmol), 2.0 mL of dry cyclohexane, and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 10 min. A solution of ketomalonate 2a (0.20 mmol) in dry cyclohexane (1.0 mL) was added dropwise to the above solution and the mixture was stirred until the starting material was completely consumed. Then the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash chromatography eluted with PE/EA (10/1 to 5/1) to afford the corresponding axially chiral arylpyrrole products (R)-3.

For 3g–3i, m, 3r, the reaction conditions are as follows: an oven-dried 10 mL of Schlenk tube was charged with arylpyrroles 1 (0.30 mmol), (S)-C8 (0.02 mmol) and 1.5 mL of mixed solvent (cyclohexane/methylcyclohexane = 1/1). After the mixture was stirred at −30 °C for 30 min, a solution of ketomalonate 2a (0.20 mmol) in 1.5 mL of mixed solvent (0.75 mL cyclohexane/0.75 mL methylcyclohexane) was added dropwise to the above solution and the mixture was stirred until the starting material was completely consumed. Then the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash chromatography eluted with PE/EA (10/1 to 5/1) to afford the corresponding axially chiral arylpyrrole products.

General procedure for the synthesis of racemic 5

An oven-dried 10 mL of Schlenk tube was charged with arylpyrrole 4 (0.20 mmol), 1 mL cyclohexane and rac-C8 (0.01 mmol) at ambient temperature. Then, ketomalonate 2a (0.10 mmol) was added to the above solution and the mixture was stirred until the starting material was completely consumed. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash column chromatography (ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to afford the corresponding racemic product 5. Notably, there was also by-product 5′ was obtained, which is the isomer of 5.

General procedure for the kinetic resolution of 4

Under nitrogen atmosphere, an oven-dried 10 mL of Schlenk tube was charged with asymmetric arylpyrroles rac-4 (0.40 mmol), (S)-C8 (0.02 mmol), 2.4 mL of dry cyclohexane, and the mixture was stirred at 30 °C for 10 min. Then, a solution of ketomalonate 2a (0.20 mmol) in dry cyclohexane (2.4 mL) was added dropwise to the above solution and the mixture was stirred until the starting material was completely consumed, then the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash chromatography eluted with PE/EA (10/1 to 5/1) to afford the corresponding axially chiral arylpyrroles product 5 and recovered substrates (R)-4.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21772081 and 21825105), Shenzhen Nobel Prize Scientists Laboratory Project (C17213101), Shenzhen Special Funds for the Development of Biomedicine, Internet, New Energy, and New Material Industries (JCYJ20170412151701379 and KQJSCX20170328153203) is greatly appreciated.

Author contributions

L.Z. performed experiments and prepared the supplementary information. S.-H.X. helped with characterizing some new compounds. B.T., J.W., J.-Q.W., and J.X. conceived and directed the project and L.Z., S.-H.X., J.W., and B.T. wrote the paper.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 1868124 and CCDC 1868125. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ data_request/cif. Supplementary information and chemical compound information are available in the online version of the paper. For NMR analysis and HPLC traces of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figures. Reprints and permissions information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to B.T. and J.W.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

4/26/2019

The original PDF version of this Article contained an error in Table 3, in which all chemical structures were omitted and only the numerical data was shown. This has been corrected in the PDF version of the Article. The HTML version was correct from the time of publication.

Contributor Information

Jun (Joelle) Wang, Email: wang.j@sustc.edu.cn.

Bin Tan, Email: tanb@sustc.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-08447-z.

References

- 1.Bringmann G, et al. Murrastifoline-F: first total synthesis, atropo-enantiomer resolution, and stereoanalysis of an axially chiral N,C-coupled biaryl alkaloid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2703–2711. doi: 10.1021/ja003488c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes CC, Prieto-Davo A, Jensen PR, Fenical W. The Marinopyrroles, antibiotics of an unprecedented structure class from a marine streptomyces sp. Org. Lett. 2008;10:629–631. doi: 10.1021/ol702952n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito C, Thoyama Y, Omura M, Kajiura I, Furukawa H. Alkaloidal constituents of murraya koenigii. isolation and structural elucidation of novel binary carbazolequinones and carbazole alkaloids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993;41:2096–2100. doi: 10.1248/cpb.41.2096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho H, et al. Effect of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and pharmacodynamics of a new proton pump inhibitor, Ilaprazole. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012;52:976–984. doi: 10.1177/0091270011408611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbarino M, et al. Possible repurposing of pyrvinium pamoate for the treatment of mesothelioma: a pre-clinical assessment. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018;233:7391–7401. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esumi H, Lu J, Kurashima Y, Hanaoka T. Antitumor activity of pyrvinium pamoate, 6-(dimethylamino)-2-[2-(2,5-dimethyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)ethenyl]-1-methyl-quinolinium pamoate salt, showing preferential cytotoxicity during glucose starvation. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aspin S, Goutierre AS, Larini P, Jazzar R, Baudoin O. Synthesis of aromatic α-aminoesters: palladium-catalyzed long-range arylation of primary CSP3–H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:10808–10811. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, et al. Selective palladium-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of olefins to branched amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:13544–13548. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millet A, Dailler D, Larini P, Baudoin O. Ligand-controlled α- and β-arylation of acyclic N-Boc amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:2678–2682. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faigl F, Mátravölgyi B, Holczbauer T, Czugler M, Madarász J. Resolution of 1-[2-carboxy-6-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid with methyl (R)-2-phenylglycinate, reciprocal resolution and second order asymmetric transformation. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2011;22:1879–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2011.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faigl F, Thurner A, Tárkányi G, Kovári J, Mordini A. Resolution and enantioselective rearrangements of amino group-containing oxiranyl ethers. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2002;13:59–68. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(02)00051-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deák S, et al. Steric and electronic tuning of atropisomeric amino alcohol type ligands with a 1-arylpyrrole backbone. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2015;26:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2015.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faigl F, et al. Synthesis of atropisomeric 1-phenylpyrrole-derived amino alcohols: new chiral ligands. Chirality. 2012;24:532–542. doi: 10.1002/chir.22049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faigl, F., Erdélyi, Z., Holczbauer, T. & Mátravölgyi, B. Highly efficient stereoconservative syntheses of new, bifunctional atropisomeric organocatalysts. Arkivoc (iii) 242–261 (2016).

- 15.Bock L, Adams R. The stereochemistry of N-Phenylpyrroles. The preparation and resolution of N-2-carboxyphenyl-2,5-dimethyl-3-carboxypyrrole. XIII. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1931;53:374–376. doi: 10.1021/ja01352a055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bock L, Adams R. Stereochemistry of phenyl pyrroles. XIX. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1931;53:3519–3522. doi: 10.1021/ja01360a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Zhang J, Ma J, Cheng DJ, Tan B. Highly atroposelective synthesis of arylpyrroles by catalytic asymmetric Paal–Knorr reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1714–1717. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Iorio N, et al. Remote control of axial chirality: aminocatalytic desymmetrization of N-arylmaleimides via vinylogous Michael addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10250–10253. doi: 10.1021/ja505610k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eudier F, Righi P, Mazzanti A, Ciogli A, Bencivenni G. Organocatalytic atroposelective formal Diels-Alder desymmetrization of N-arylmaleimides. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1728–1731. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Iorio N, et al. Targeting remote axial chirality control of N-(2-tert-butylphenyl)succinimides by means of Michael addition type reactions. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:5191–5201. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2016.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen YH, et al. Atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral biaryldiols via organocatalytic arylation of 2-naphthols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:15062–15065. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi LW, Mao JH, Zhang J, Tan B. Organocatalytic asymmetric arylation of indoles enabled by azo groups. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:58–64. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong RJ, Smith MD. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of atropisomeric biaryls: a cation-directed nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:12822–12826. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi T, Niizuma S, Kamikawa T, Suzuki N, Uozumi Y. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of axially chiral biaryls by palladium-catalyzed enantioposition-selective cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9101–9102. doi: 10.1021/ja00140a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori K, et al. Enantioselective synthesis of multisubstituted biaryl skeleton by chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed desymmetrization/kinetic resolution sequence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3964–3970. doi: 10.1021/ja311902f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang JW, et al. Discovery and enantiocontrol of axially chiral urazoles via organocatalytic tyrosine click reaction. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10677. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng DJ, et al. Highly enantioselective kinetic resolution of axially chiral BINAM derivatives catalyzed by a Brønsted acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3684–3687. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafson JL, Lim D, Miller SJ. Dynamic kinetic resolution of biaryl atropisomers via peptide-catalyzed asymmetric bromination. Science. 2010;328:1251–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1188403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu S, Poh SB, Zhao Y. Kinetic resolution of 1,1′-biaryl-2,2′-diols and amino alcohols through NHC-catalyzed atroposelective acylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:11041–11045. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma G, Deng J, Sibi MP. Fluxionally chiral DMAP catalysts: kinetic resolution of axially chiral biaryl compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:11818–11821. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma G, Sibi MP. Catalytic kinetic resolution of biaryl compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 2015;21:11644–11657. doi: 10.1002/chem.201500869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirakawa S, Wu X, Maruoka K. Kinetic resolution of axially chiral 2-amino-1,1′-biaryls by phase-transfer-catalyzed N-allylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:14200–14203. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernardi L, Lopez-Cantarero J, Niess B, Jørgensen KA. Organocatalytic asymmetric 1,6-additions of β-ketoesters and glycine imine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5772–5778. doi: 10.1021/ja0707097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chauhan P, Kaya U, Enders D. Advances in organocatalytic 1,6-addition reactions: enantioselective construction of remote stereogenic centers. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017;359:888–912. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201601342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Csaky AG, de la Herran G, Murcia MC. Conjugate addition reactions of carbon nucleophiles to electron-deficient dienes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:4080–4102. doi: 10.1039/b924486g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcos V, Alemán J. Old tricks, new dogs: organocatalytic dienamine activation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:6812–6832. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00438E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terada M, Yokoyama S, Sorimachi K, Uraguchi D. Chiral phosphoric acid-catalyzed enantioselective aza-Friedel–Crafts reaction of indoles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:1863–1867. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200700151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correia JTM, List B, Coelho F. Catalytic asymmetric conjugate addition of indolizines to α,β-unsaturated ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:7967–7970. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li G, Rowland GB, Rowland EB, Antilla JC. Organocatalytic enantioselective Friedel–Crafts reaction of pyrrole derivatives with imines. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4065–4068. doi: 10.1021/ol701881j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu C, Han P, Wu X, Tang M. The mechanism investigation of chiral phosphoric acid-catalyzed Friedel-Crafts reactions-how the chiral phosphoric acid regains the proton. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014;1050:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng J, et al. The highly enantioselective addition of indoles and pyrroles to isatins-derived N-Boc ketimines catalyzed by chiral phosphoric acids. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:8003–8005. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33200k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Y, et al. Direct synthesis of chiral 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazines via a catalytic asymmetric intramolecular aza-Friedel–Crafts reaction. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4490–4493. doi: 10.1021/ol2018328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowland GB, Rowland EB, Liang Y, Perman JA, Antilla JC. The highly enantioselective addition of indoles to N-acyl imines with use of a chiral phosphoric acid catalyst. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2609–2611. doi: 10.1021/ol0703579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rueping M, Nachtsheim BJ, Moreth SA, Bolte M. Asymmetric Brønsted acid catalysis: enantioselective nucleophilic substitutions and 1,4-additions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:593–596. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loosley BC, Andersen RJ, Dake GR. Total synthesis of Cladoniamide G. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1152–1154. doi: 10.1021/ol400055v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouhlel A, Curti C, Vanelle P. New methodology for the synthesis of thiobarbiturates mediated by manganese(III) acetate. Molecules. 2012;17:4313–4325. doi: 10.3390/molecules17044313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Estévez V, Villacampa M, Menéndez JC. Recent advances in the synthesis of pyrroles by multicomponent reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:4633–4657. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60015G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan XM, et al. La(OTf)3 catalyzed synthesis of α-aryl tetrasubstituted pyrroles through [4 + 1] annulation under microwave irradiation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.11.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiao L, Hao E, Vicente MGH, Smith KM. Improved synthesis of functionalized 2,2′-bipyrroles. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8119–8122. doi: 10.1021/jo701310k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yao L, et al. Chiral ferrocenyl N,N Ligands with intramolecular hydrogen bonds for highly enantioselective allylic alkylations. ChemCatChem. 2018;10:804–809. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201701461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gridnev ID, Kouchi M, Sorimachi K, Terada M. On the mechanism of stereoselection in direct Mannich reaction catalyzed by BINOL-derived phosphoric acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rueping M, Nachtsheim BJ, Ieawsuwan W, Atodiresei I. Modulating the acidity: highly acidic Brønsted acids in asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6706–6720. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 1868124 and CCDC 1868125. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ data_request/cif. Supplementary information and chemical compound information are available in the online version of the paper. For NMR analysis and HPLC traces of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figures. Reprints and permissions information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to B.T. and J.W.