Abstract

Stress is associated with poorer physical and mental health. To improve our understanding of this link, we performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of depressive symptoms and genome-wide by environment interaction studies (GWEIS) of depressive symptoms and stressful life events (SLE) in two UK population-based cohorts (Generation Scotland and UK Biobank). No SNP was individually significant in either GWAS, but gene-based tests identified six genes associated with depressive symptoms in UK Biobank (DCC, ACSS3, DRD2, STAG1, FOXP2 and KYNU; p < 2.77 × 10−6). Two SNPs with genome-wide significant GxE effects were identified by GWEIS in Generation Scotland: rs12789145 (53-kb downstream PIWIL4; p = 4.95 × 10−9; total SLE) and rs17070072 (intronic to ZCCHC2; p = 1.46 × 10−8; dependent SLE). A third locus upstream CYLC2 (rs12000047 and rs12005200, p < 2.00 × 10−8; dependent SLE) when the joint effect of the SNP main and GxE effects was considered. GWEIS gene-based tests identified: MTNR1B with GxE effect with dependent SLE in Generation Scotland; and PHF2 with the joint effect in UK Biobank (p < 2.77 × 10−6). Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) analyses incorporating GxE effects improved the prediction of depressive symptom scores, when using weights derived from either the UK Biobank GWAS of depressive symptoms (p = 0.01) or the PGC GWAS of major depressive disorder (p = 5.91 × 10−3). Using an independent sample, PRS derived using GWEIS GxE effects provided evidence of shared aetiologies between depressive symptoms and schizotypal personality, heart disease and COPD. Further such studies are required and may result in improved treatments for depression and other stress-related conditions.

Introduction

Mental illness results from the interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental risk factors1,2. Previous studies have shown that the effects of environmental factors on traits may be partially heritable3 and moderated by genetics4,5. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common psychiatric disorder with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 14% globally6 and with a heritability of approximately 37%7. There is strong evidence for the role of stressful life events (SLEs) as risk factor and trigger for depression8–12. Genetic control of sensitivity to stress may vary between individuals, resulting in individual differences in the depressogenic effects of SLE, i.e., genotype-by-environment interaction (GxE)4,13–16. Significant evidence of GxE has been reported for common respiratory diseases and some forms of cancer17–22, and GxE studies have identified genetic risk variants not found by genome-wide association studies (GWAS)23–27.

Interaction between polygenic risk of MDD and recent SLE are reported to increase liability to depressive symptoms4,16; validating the implementation of genome-wide approaches to study GxE in depression. Most GxE studies for MDD have been conducted on candidate genes, or using polygenic approaches to a wide range of environmental risk factors, with some contradictory findings28–32. Incorporating knowledge about recent SLE into GWAS may improve our ability to detect risk variants in depression otherwise missed in GWAS33. To date, three studies have performed genome-wide by environment interaction studies (GWEIS) of MDD and SLE34–36, but this is the first study to perform GWEIS of depressive symptoms using adult SLE in cohorts of relatively homogeneous European ancestry.

Interpretation of GxE effects may be hindered by gene–environment correlation. Gene–environment correlation denotes a genetic mediation of associations through genetic influences on exposure to, or reporting of, environments2,37. Genetic factors predisposing to MDD may contribute to exposure and/or reporting of SLE38. To tackle this limitation, measures of SLE can be broken down into SLE likely to be independent of a respondent’s own behaviour and symptoms, or into dependent SLE, in which participants may play an active role exposure to SLE39,40. Different genetic influences, including a higher heritability, are reported for dependent SLE compared to independent SLE38,41–44, suggesting that whereas GxE driven by independent SLE is likely to reflect a genetic moderation of associations between SLE and depression, GxE driven by dependent SLE may result from a genetic mediation of the association through genetically driven personality or behavioural traits. To test this, we analysed dependent and independent SLE scores separately in Generation Scotland (GS).

Stress contributes to many human conditions, with evidence of genetic vulnerability to the effect of SLE45. Therefore, genetic stress-response factors in MDD may also underlie the aetiology of other stress-linked disorders with which MDD is often comorbid46,47 (e.g., cardiovascular diseases48, diabetes49, chronic pain50 and inflammation51). We tested the hypothesis that pleiotropy and shared aetiology between mental and physical health conditions may be due in part to genetic variants underlying SLE effects in depression.

In this study, we conduct GWEIS of depressive symptoms incorporating data on SLE in two independent UK-based cohorts. We aimed to: (i) identify loci associated with depressive symptoms through genetic response to SLE; (ii) study dependent and independent SLE to support a contribution of genetically mediated exposure to stress; (iii) assess whether GxE effects improve the proportion of phenotypic variance in depressive symptoms explained by genetic additive main effects alone; and (iv) test for a significant overlap in the genetic aetiology of the response to SLE and mental and physical stress-related phenotypes.

Materials and methods

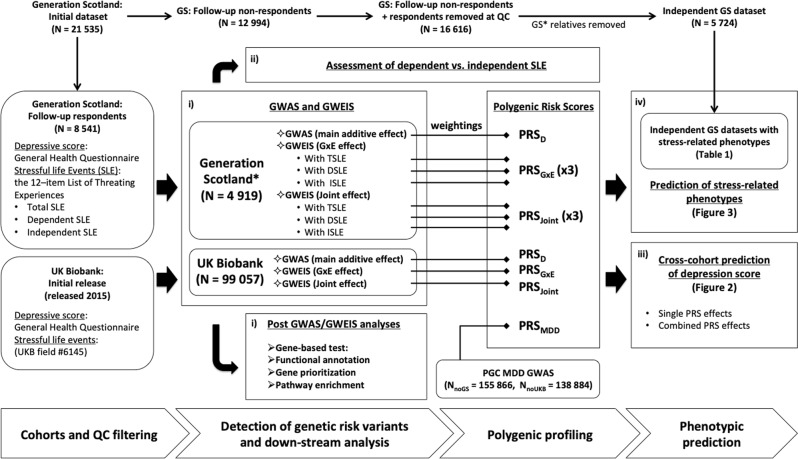

The core workflow of this study is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Study flowchart.

Overview of the analyses conducted in this study: (i) identify loci associated with depressive symptoms through genetic response to SLE; (ii) test whether results of studying dependent and independent SLE support a contribution of genetically mediated exposure to stress; (iii) assess whether GxE effects improve the proportion of phenotypic variance in depressive symptoms explained by genetic additive main effects alone and (iv) test whether there is significant overlap in the genetic aetiology of the response to SLE and mental and physical stress-related phenotypes. Two core cohorts are used, Generation Scotland (GS) and UK Biobank (UKB). Summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and genome-wide by environment interaction studies (GWEIS) are used to generate polygenic risk scores (PRSs). Summary statistics from Psychiatric Genetic Consortium (PGC) Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) GWAS are also used to generate PRS (PRSMDD). PRS weighted by: additive effects (PRSD and PRSMDD), GxE effects (PRSGxE) and joint effects (the combined additive and GxE effect; PRSJoint), are used for phenotypic prediction. TSLE stands for total number of SLE reported. DSLE stands for SLE dependent on an individual’s own behaviour. Conversely, ISLE stands for independent SLE. N stands for sample size. NnoGS stands for sample size with GS individuals removed. NnoUKB stands for sample size with UKB individuals removed

Cohort descriptions

GS

GS is a family-based population cohort representative of the Scottish population52. At baseline, blood and salivary DNA samples were collected, stored and genotyped at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Edinburgh. Genome-wide genotype data were generated using the Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome-8 v1.0 DNA Analysis BeadChip (San Diego, CA, USA) and Infinium chemistry53. The procedures and details for DNA extraction and genotyping have been extensively described elsewhere54,55. In total, 21,525 participants were re-contacted to participate in a follow-up mental health study (Stratifying Resilience and Depression Longitudinally, STRADL), of which 8541 participants responded providing updated measures in psychiatric symptoms and SLE through self-reported mental health questionnaires56. Samples were excluded if: they were duplicate samples, had diagnoses of bipolar disorder, no SLE data (non-respondents), were population outliers (mainly non-Caucasians and Italian ancestry subgroup), had sex mismatches or were missing >2% of genotypes. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were excluded if: missing >2% of genotypes, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test p < 1 × 10−6, or minor allele frequency <1%. Further details of the GS and STRADL cohort are available elsewhere52,56–58. All components of GS and STRADL obtained ethical approval from the Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics on behalf of the NHS (reference 05/s1401/89). After quality control, individuals were filtered by degree of relatedness (pi-hat < 0.05), maximising retention of those individuals reporting a higher number of SLE. The final dataset comprised data on 4919 unrelated individuals (1929 men; 2990 women) and 560,351 SNPs.

Independent GS datasets

Additional datasets for a range of stress-linked medical conditions and personality traits were created from GS (N = 21,525) excluding respondents and their relatives (N = 5724). Following the same quality control criteria detailed above, we maximised unrelated non-respondents for retention of cases, or proxy cases (see below), to maximise the information available for each phenotype. This resulted in independent datasets with unrelated individuals for each trait. Differences between respondents and non-respondents are noted in the figure legend of Table 1.

Table 1.

GS samples with stress-related phenotypes

| Trait | N | Males/females | N SNPs | N Cases | N Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer (R) | 3377 | 1475/1903 | 560,622 | 655 | 2722 |

| Asthma | 3390 | 1500/1890 | 560,569 | 555 | 2835 |

| Asthma (R) | 3375 | 1470/1905 | 560,432 | 910 | 2465 |

| Bowel cancer (R) | 3386 | 1495/1891 | 560,630 | 672 | 2714 |

| Breast cancer | 3388 | 1486/1902 | 560,611 | 83 | 3305 |

| Breast cancer (R) | 3386 | 1482/1904 | 560,579 | 564 | 2822 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3387 | 1496/1891 | 560,591 | 73 | 3314 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (R) | 3387 | 1474/1913 | 560,620 | 553 | 2834 |

| Depression | 3385 | 1495/1890 | 560,584 | 483 | 2902 |

| Depression (R) | 3382 | 1506/1876 | 560,514 | 731 | 2651 |

| Diabetes | 3388 | 1497/1891 | 560,469 | 185 | 3203 |

| Diabetes (R) | 3389 | 1481/1908 | 560,584 | 1144 | 2245 |

| Heart disease | 3392 | 1504/1888 | 560,526 | 212 | 3180 |

| Heart disease (R) | 3377 | 1483/1894 | 560,479 | 2254 | 1123 |

| High blood pressure | 3402 | 1501/1901 | 560,508 | 729 | 2673 |

| High blood pressure (R) | 3372 | 1464/1908 | 560,569 | 1901 | 1471 |

| Hip fracture (R) | 3388 | 1489/1899 | 560,572 | 421 | 2967 |

| Lung cancer (R) | 3379 | 1492/1887 | 560,600 | 798 | 2581 |

| Osteoarthritis | 3395 | 1486/1909 | 560,640 | 411 | 2984 |

| Osteoarthritis (R) | 3383 | 1466/1917 | 560,516 | 961 | 2422 |

| Parkinson (R) | 3388 | 1488/1900 | 560,590 | 236 | 3152 |

| Prostate cancer (R) | 3381 | 1495/1886 | 560,570 | 329 | 3052 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3387 | 1490/1897 | 560,618 | 93 | 3294 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (R) | 3380 | 1487/1893 | 560,543 | 765 | 2615 |

| Stroke | 3387 | 1492/1895 | 560,613 | 81 | 3306 |

| Stroke (R) | 3385 | 1463/1922 | 560,478 | 1506 | 1879 |

| Neuroticisma | 3421 | 1521/1900 | 560,484 | – | – |

| Extraversiona | 3420 | 1520/1900 | 560,476 | – | – |

| Schizotypal personalitya | 2386 | 1065/1321 | 560,369 | – | – |

| Mood disordera | 2307 | 1040/1267 | 560,318 | – | – |

Samples were maximised for retention of cases to maximise the information available for each trait. There was no preferential selection of relatives in pairs for quantitative phenotypes, in order to retain the underlying distribution. All individuals involved in the datasets listed above were non-respondents to the GS follow-up study. Compared with individuals included at GS GWEIS (respondents in GS follow-up), non-respondents were significantly: younger, from more socioeconomically deprived areas, generally less healthier and wealthier. Non-respondents were more likely to smoke, and less likely to drink alcohol, although they consumed more units per week, compared with respondents. At GS baseline, non-respondents experienced more psychological distress and reported higher scores in symptoms of GHQ-depression and GHQ-anxiety than respondents56

The total target sample size (N), number of males and females in N, number of SNPs (N SNPs) in target sample size N: the number of SNPs used as predictors after clumping step range between 90,650 and 91,000. The number of cases and controls in the independent target sample is indicated for binary phenotypes only. Samples were mapping by proxy approach was used (i.e., where first-degree relatives of individuals with the disease were considered proxy cases and included into the group of cases) are indicated by (R)

GS Generation Scotland, GWEIS genome-wide by environment interaction studies, GHQ General Health Questionnaire

aAssessed through self-reported questionnaires

UK Biobank (UKB)

This study used data from 99,057 unrelated individuals (47,558 men; 51,499 women) from the initial release of UKB genotyped data (released 2015; under UKB project 4844). Briefly, participants were removed based on UKB genomic analysis exclusion, non-white British ancestry, high missingness, genetic relatedness (kinship coefficient > 0.0442), QC failure in UK BiLEVE study and gender mismatch. GS participants and their relatives were excluded and GS SNPs imputed to a reference set combining the UK10K haplotype and 1000 Genomes Phase 3 reference panels59. After quality control, 1,009,208 SNPs remained. UKB received ethical approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service North West (reference: 11/NW/0382). Further details on UKB cohort description, genotyping, imputation and quality control are available elsewhere60–62.

All participants provided informed consent.

Phenotype assessment

SLEs

GS participants reported SLE experienced over the preceding 6 months through a self-reported brief life events questionnaire based on the 12-item list of threatening experiences39,63,64 (Supplementary Table 1a). The total number of SLE reported (TSLE) consisted of the number of ‘yes’ responses. TSLE were subdivided into SLE potentially dependent or secondary to an individual’s own behaviour (DSLE, questions 6–11 in Supplementary Table 1a), and independent SLE (ISLE, questions 1–5 in Supplementary Table 1a; pregnancy item removed) following Brugha et al.39,40. Thus, three SLE measures (TSLE, DSLE and ISLE) were constructed for GS. UKB participants were screened for ‘illness, injury, bereavement and stress’’ (Supplementary Table 1b) over the previous 2 years using six items included in the UKB Touchscreen questionnaire. A score reflecting SLE reported in UKB (TSLEUKB) was constructed by summing the number of ‘yes’ responses.

Psychological assessment

GS participants reported whether their current mental state over the preceding 2 weeks differed from their typical state using a self-administered 28-item scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)65–67. Participants rated the degree and severity of their current symptoms with a four-point Likert scale (following Goldberg et al.67). A final log-transformed GHQ was used to detect altered psychopathology and thus, assess depressive symptoms as results of SLE. In UKB participants, current depressive symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks were evaluated using four psychometric screening items (Supplementary Table 2), including two validated and reliable questions for screening depression68, from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) validated to screen mental illness69,70. Each question was rated in a four-point Likert scale to assess impairment/severity of symptoms. Due to its skewed distribution, a four-point PHQ score was formed from PHQ (0 = 0; 1 = 1–2; 2 = 3–5; 3 = 6 or more) to create a more normal distribution.

Stress-related traits

Targeted GS stress-related phenotypes and sample sizes are shown in Table 1 and detailed elsewhere52. These conditions were selected from literature review based on previous evidence of a link with stress45 (see also Supplementary Material: third section). Furthermore, we created additional independent samples using mapping by proxy, where individuals with a self-reported first-degree relative with a selected phenotype were included as proxy cases. This approach provides greater power to detect susceptibility variants in traits with low prevalence71.

Statistical analyses

SNP-heritability and genetic correlation

A restricted maximum likelihood approach was applied to estimate SNP-heritability (h2SNP) of depressive symptoms and self-reported SLE measures, and within samples bivariate genetic correlation between depressive symptoms and SLE measures using GCTA72.

GWAS analyses

GWAS were conducted in PLINK73. In GS, age, sex and 20 principal components (PCs) were fitted as covariates. In UKB, age, sex and 15 PCs recommended by UKB were fitted as covariates. The genome-wide significance threshold was p = 5 × 10–8.

GWEIS analyses

GWEIS were conducted on GHQ (the dependent variable) for TSLE, DSLE and ISLE in GS and on PHQ for TSLEUKB in UKB fitting the same covariates detailed above to reduce error variance. GWEIS were conducted using an R plugin for PLINK73 developed by Almli et al.74 (https://epstein-software.github.io/robust-joint-interaction). This method implements a robust test that jointly considers SNP and SNP–environment interaction effects from a full model (Y ~ β0 + βSNP + βSLE + βSNPxSLE + βCovariates) against a null model where both the SNP and SNP×SLE effects equal 0, to assess the joint effect (the combined additive main and GxE genetic effect at a SNP) using a nonlinear statistical approach that applies Huber–White estimates of variance to correct possible inflation due to heteroscedasticity (unequal variances across exposure levels). This robust test should reduce confounding due to differences in variance induced by covariate interaction effects if present75. Additional code was added (courtesy of Prof. Michael Epstein;74 Supplementary Material) to generate beta-coefficients and the p-value of the GxE term alone. In UKB, correcting for 1,009,208 SNPs and one exposure, we established a Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance at p = 2.47 × 10–8 for both joint and GxE effects. In GS, correcting for 560,351 SNPs and three measures of SLE we established a genome-wide significance threshold of p = 2.97 × 10–8.

Post-GWAS/GWEIS analyses

GWAS and GWEIS summary statistics were analysed using FUMA76 including: gene-based tests, functional annotation, gene prioritisation and pathway enrichment (Supplementary Material).

Polygenic profiling and prediction

Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) weighting by GxE effects (PRSGxE) were generated using PRSice-277 (Supplementary Material) in GS using GxE effects from UKB-GWEIS. In UKB, PRSGxE were constructed using GxE effects from all three GS-GWEIS (TSLE, DSLE and ISLE as exposures) independently. PRS were also weighted in both samples using either UKB-GWAS or GS-GWAS statistics (PRSD), and summary statistics from Psychiatric Genetic Consortium (PGC) MDD-GWAS (released 2016; PRSMDD) that excluded GS and UKB individuals when required (NnoGS = 155,866; NnoUKB = 138,884). Furthermore, we calculated PRS weighted by the joint effects (the combined additive main and GxE genetic effects; PRSJoint) from either the UKB-GWEIS or GS-GWEIS. PRS predictions of depressive symptoms were permuted 10,000 times. Multiple regression models fitting PRSGxE and PRSMDD, and both PRSGxE and PRSD were tested. All models were adjusted by same covariates used in GWAS/GWEIS. Null models were estimated from the direct effects of covariates alone. The predictive improvement of combining PRSGxE and PRSMDD/PRSD effects over PRSMDD/PRSD effects alone was tested for significance using the likelihood ratio test (LRT).

Prediction of PRSD, PRSGxE and PRSJoint of stress-linked traits were adjusted by age, sex and 20 PCs; and permuted 10,000 times. Empirical-p-values after permutations were further adjusted by false discovery rate (FDR, conservative threshold at Empirical-p = 6.16 × 10–3). The predictive improvement of fitting PRSGxE combined with PRSD and covariates over prediction of a phenotype using the PRSD effect alone with covariates was assessed using LRT, and LRT-p-values adjusted by FDR (conservative threshold at LRT-p = 8.35 × 10–4).

Results

Phenotypic and genetic correlations

Depressive symptom scores and SLE measures were positively correlated in both UKB (r2 = 0.22, p < 2.2 × 10–16) and GS (TSLE-r2 = 0.21, p = 1.69 × 10−52; DSLE-r2 = 0.21, p = 8.59 × 10−51; ISLE-r2 = 0.17, p = 2.33 × 10−33). Significant bivariate genetic correlation between depression and SLE scores was identified in UKB (rG = 0.72; p < 1 × 10−5, N = 50,000), but not in GS (rG = 1, p = 0.056, N = 4919; Supplementary Table 3a).

SNP-heritability (h2SNP)

In UKB, a significant h2SNP of PHQ was identified (h2SNP = 0.090; p < 0.001; N = 99,057). This estimate remained significant after adjusting by TSLEUKB effect (h2SNP = 0.079; p < 0.001), suggesting a genetic contribution unique to depressive symptoms. The h2SNP of TSLEUKB was also significant (h2SNP = 0.040, p < 0.001; Supplementary Table 3b). In GS, h2SNP was not significant for GHQ (h2SNP = 0.071, p = 0.165; N = 4919). However, in an ad hoc estimation from the baseline sample of 6751 unrelated GS participants (details in Supplementary Table 3b) we detected a significant h2SNP for GHQ (h2SNP = 0.135; p < 5.15 × 10−3), suggesting that the power to estimate h2SNP in GS may be limited by sample size. Estimates were not significant for either TSLE (h2SNP = 0.061, p = 0.189; Supplementary Table 3b) or ISLE (h2SNP = 0.000, p = 0.5), but h2SNP was significant for DSLE (h2SNP = 0.131, p = 0.029), supporting a potential genetic mediation and gene–environment correlation.

GWAS of depressive symptoms

No genome-wide significant SNPs were detected by GWAS in either cohort. Top findings (p < 1 × 10−5) are summarised in Supplementary Table 4. Manhattan and QQ plots are shown in Supplementary Figures 1-4. There was no evidence of genomic inflation (all λ1000 < 1.01).

Post-GWAS analyses

Gene-based test identified six genes associated with PHQ using the UKB-GWAS statistics at genome-wide significance (Bonferroni-corrected p = 2.77 × 10−6; DCC, p = 7.53 × 10−8; ACSS3, p = 6.51 × 10−7; DRD2, p = 6.55 × 10−7; STAG1, p = 1.63 × 10−6; FOXP2, p = 2.09 × 10−6; KYNU, p = 2.24 × 10−6; Supplementary Figure 8). Prioritised genes based on position, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) and chromatin interaction mapping are detailed in Supplementary Table 5. No genes were detected in GS-GWAS gene-based test (Supplementary Figures 9). No tissue-specific enrichment was detected from GWAS in either cohort. Significant gene-sets and GWAS catalogue associations for UKB-GWAS are reported in Supplementary Table 6. These included the biological process: positive regulation of long-term synaptic potentiation, and GWAS catalogue associations: brain structure, schizophrenia, response to amphetamines, age-related cataracts (age at onset), fibrinogen, acne (severe), fibrinogen levels and educational attainment; all adjusted-p < 0.01. There was no significant gene-set enrichment from GS-GWAS.

GWEIS of depressive symptoms

Manhattan and QQ plots are shown in Supplementary Figures 1-4. There was no evidence of GWEIS inflation for either UKB or GS (all λ1000 < 1.01). No genome-wide significant GWEIS associations were detected for SLE in UKB. GS-GWEIS using TSLE identified a significant GxE effect (p < 2.97 × 10−8) at an intragenic SNP on chromosome 11 (rs12789145, p = 4.95 × 10−9, β = 0.06, closest gene: PIWIL4; Supplementary Figure 5), and using DSLE at an intronic SNP in ZCCHC2 on chromosome 18 (rs17070072, p = 1.46 × 10−8, β = −0.08; Supplementary Figure 6). In their corresponding joint effect tests, both rs12789145 (p = 2.77 × 10−8) and rs17070072 p = 1.96 × 10−8) were significant. GWEIS for joint effect using DSLE identified two further significant SNPs on chromosome 9 (rs12000047, p = 2.00 × 10−8, β = −0.23; rs12005200, p = 2.09 × 10−8, β = −0.23, LD r2 > 0.8, closest gene: CYLC2; Supplementary Figure 7). None of these associations replicated in UKB (p > 0.05), although the effect direction was consistent between cohorts for the SNP close to PIWL1 and SNPs at CYLC2. No SNP achieved genome-wide significant association in the GS-GWEIS using ISLE as exposure. Top GWEIS results (p < 1 × 10−5) are summarised in Supplementary Tables 7-10.

Post-GWEIS analyses: gene-based tests

All results are shown in Supplementary Figures 10-17. Two genes were associated with PHQ using the joint effect from the UKB-GWEIS (ACSS3 p = 1.61 × 10−6; PHF2, p = 2.28 × 10−6; Supplementary Figure 11). ACSS3 was previously identified using the additive main effects, whereas PHF2 was only significantly associated using the joint effects. Gene-based tests identified MTNR1B as significantly associated with GHQ on the GS-GWEIS using DSLE in both GxE (p = 1.53 × 10−6) and joint effects (p = 2.38 × 10−6; Supplementary Figures 14-15).

Post-GWEIS analyses: tissue enrichment

We prioritised genes based on position, eQTL and chromatin interaction mapping in brain tissues and regions. In UKB, prioritised genes using GxE effects were enriched for upregulated differentially expressed genes from adrenal gland (adjusted-p = 3.58 × 10−2). Using joint effects, prioritised genes were enriched on upregulated differentially expressed genes from artery tibial (adjusted-p = 4.34 × 10−2). In GS, prioritised genes were enriched: in upregulated differentially expressed genes from artery coronary (adjusted-p = 4.55 × 10−2) using GxE effects with DSLE; in downregulated differentially expressed genes from artery aorta tissue (adjusted-p = 4.71 × 10−2) using GxE effects with ISLE; in upregulated differentially expressed genes from artery coronary (adjusted-p = 5.97 × 10−3, adjusted-p = 9.57 × 10−3) and artery tibial (adjusted-p = 1.05 × 10−2, adjusted-p = 1.55 × 10−2) tissues using joint effects with both TSLE and DSLE; and in downregulated differentially expressed genes from lung tissue (adjusted-p = 3.98 × 10−2) and in up- and downregulated differentially expressed genes from the spleen (adjusted-p = 4.71 × 10−2) using joint effects with ISLE. There was no enrichment using GxE effect with TSLE.

Post-GWEIS analyses: gene-sets enrichment

Significant gene-sets and GWAS catalogue hits from GWEIS are detailed in Supplementary Tables 11-14, including for UKB Biocarta: GPCR pathway; Reactome: opioid signalling, neurotransmitter receptor binding and downstream transmission in the postsynaptic cell, transmission across chemical synapses, gastrin CREB signalling pathway via PKC and MAPK; GWAS catalogue: post bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio, migraine and body mass index. In GS, enrichment was seen using TSLE and DLSE for GWAS catalogue: age-related macular degeneration, myopia, urate levels and Heschl’s gyrus morphology; and using ISLE for biological process: regulation of transporter activity. All adjusted-p < 0.01.

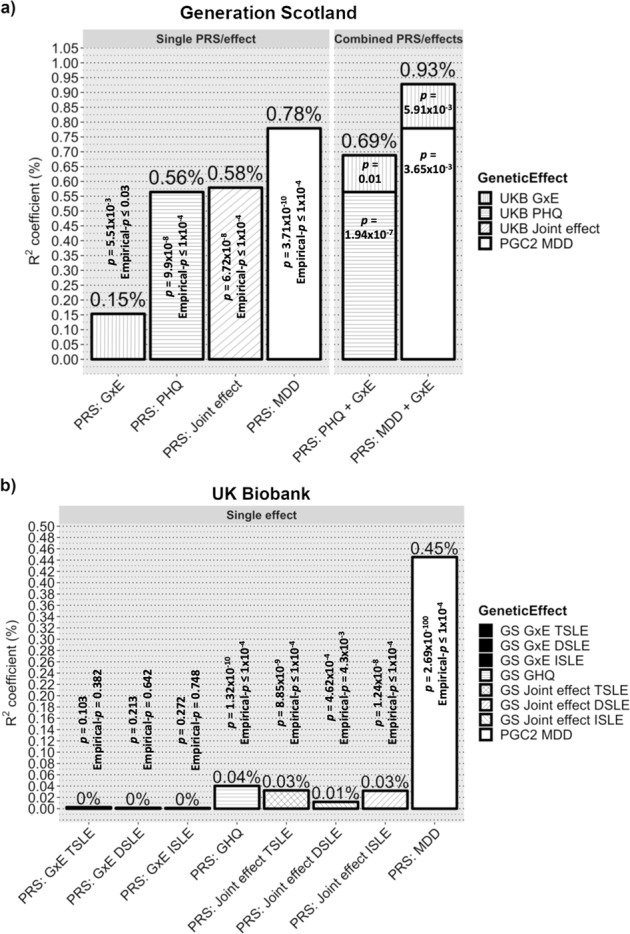

Cross-cohort prediction

In GS, PRSD weighted by the UKB-GWAS of PHQ significantly explained 0.56% of GHQ variance (Empirical-p < 1.10−4), similar to PRSMDD weighted by PGC MDD-GWAS (R2 = 0.78%, Empirical-p < 1.10−4). PRSGxE weighted by the UKB-GWEIS GxE effects explained 0.15% of GHQ variance (Empirical-p = 0.03, Supplementary Table 15). PRSGxE fitted jointly with PRSMDD significantly improved prediction of GHQ (R2 = 0.93%, model p = 6.12 × 10−11; predictive improvement of 19%, LRT-p = 5.91 × 10−3) compared with PRSMDD alone. Similar to PRSGxE with PRSD (R2 = 0.69%, model p = 2.72 × 10−8; predictive improvement of 23%, LRT-p = 0.01). PRSJoint weighted by the UKB-GWEIS also predicted GHQ (R2 = 0.58%, Empirical-p < 1.10−4), although the variance explained was significantly reduced compared with the model fitting PRSGxE and PRSD together (LRT-p = 4.69 × 10−7), suggesting that additive and GxE effects should be modelled independently for polygenic approaches (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Prediction of depression scores by PRSGxE, PRSD, PRSMDD and PRSJoint.

Variance of depression score explained by PRSGxE PRSD, PRSMDD and PRSJoint as single effect; and combining both PRSD and PRSMDD with PRSGxE in single models. Prediction was conducted using a Generation Scotland (GS) and b UK Biobank (UKB) as target sample. PRSGxE were weighted by cross- sample genome-wide by environment interaction studies (GWEIS) using GxE effect. PRSD were weighted by cross-sample genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of depressive symptoms effect. PRSMDD was weighted by Psychiatric Genetic Consortium (PGC) Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)-GWAS summary statistics. PRSJoint were weighted by cross-sample GWEIS using joint effect. A nominally significant gain in variance explained of General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) of about 23% was seen in GS when PRSGxE was incorporated into a multiple regression model along with PRSD; and of about 19% when PRSGxE was incorporated into a multiple regression model along with PRSMDD. Such a gain was not seen in UKB, but it must be noted that both PRSD and PRSMDD also explains much less variance of PHQ in UKB than of GHQ in GS. Also note, a noticeably reduction of variance explained by PRSJoint compared with combined polygenic risk scores (PRS)/effects

In UKB (Fig. 2b), both PRSD weighted by the GS-GWAS of GHQ and PRSMDD significantly explained 0.04 and 0.45% of PHQ variance, respectively (both Empirical-p < 1.10−4; Supplementary Table 15). PRSGxE derived from the GS-GWEIS GxE effect did not significantly predicted PHQ (TSLE-PRSGxE Empirical-p = 0.382; DSLE-PRSGxE Empirical-p = 0.642; ISLE-PRSGxE Empirical-p = 0.748). Predictive improvements using the PRSGxE effect fitted jointly with PRSMDD or PRSD were not significant (all LRT-p > 0.08). PRSJoint significantly predicted PHQ (TSLE-PRSJoint: R2 = 0.032%, Empirical-p < 1.10−4; DSLE-PRSJoint: R2 = 0.012%, Empirical-p = 4.3 × 10−3; ISLE-PRSJoint: R2 = 0.032%, Empirical-p < 1.10−4), although the variance explained was significantly reduced compared with the models fitting PRSGxE and PRSD together (all LRT-p < 1.48 × 10−3).

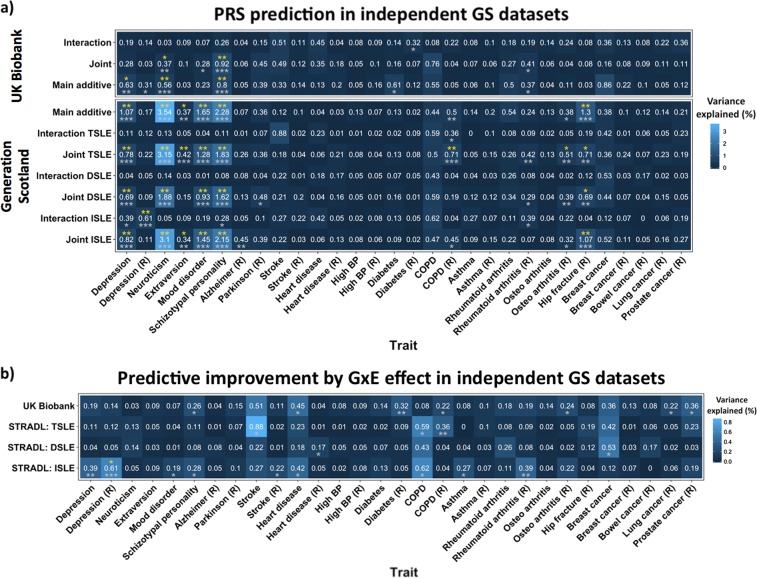

Prediction of stress-related traits

Prediction of stress-related traits in independent samples using PRSD, PRSGxE and PRSJoint are summarised in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 16. Significant trait prediction after FDR adjustment (Empirical-p < 6.16 × 10−3, FDR-adjusted Empirical-p < 0.05) using both UKB and GS PRSD was seen for: depression status, neuroticism and schizotypal personality. PRSGxE weighted by the GS-GWEIS GxE effect using ISLE significantly predicted depression status mapped by proxy (Empirical-p = 7.00 × 10−4, FDR-adjusted Empirical-p = 9.54 × 10−3).

Fig. 3. Polygenic risk score (PRS) prediction in independent Generation Scotland (GS) datasets.

a Heatmap illustrating PRS prediction of a wide range of traits from GS listed in the x axis (Table 1). (R) refers to traits using mapping by proxy approach (i.e., where first-degree relatives of individuals with the disease are considered proxy cases and included into the group of cases). Y axis shows the discovery sample and the effect used to weight PRS. Numbers in cells indicate the % of variance explained, also represented by colour scale. Significance is represented by asterixes according to the following significance codes: **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; in grey Empirical-p-values after permutation (10,000 times) and in yellow FDR-adjusted Empirical-p-values. b Predictive improvement by GxE effect in independent GS datasets. Heatmap illustrating the predictive improvement as a result of incorporating PRSGxE into a multiple model along with PRSD and covariates (full model), over a model fitting PRSD alone with covariates (null model); predicting a wide range of traits from GS listed in the x axis (Table 1). Covariates: age, sex and 20 PCs. (R) refers to traits using mapping by proxy approach (i.e., where first-degree relatives of individuals with the disease are consider proxy cases and included into the group of cases). PRSGxE are weighted by genome-wide by environment interaction studies (GWEIS) using GxE effects. PRSD were weighted by the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of depressive symptoms additive main effects. The y axis shows the discovery sample used to weight PRS. Numbers in cells indicate the % of variance explained by the PRSGxE, also represented by colour scale. Notice that those correspond to the PRSGxE predictions in Fig. 3a when PRSGxE are weighted by GxE effects. Significance was tested by likelihood ratio tests (LRT): full model including PRSD + PRSGxE vs. null model with PRSD alone (covariates adjusted). Significance is represented by asterixes according to the following significance codes: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; in grey LRT-p-values and in yellow FDR-adjusted LRT-p-values

Nominally significant predictive improvements (LRT-p < 0.05) of fitting PRSGxE, over the PRSD effect alone, using summary statistics generated from both UKB and GS were detected for schizotypal personality, heart diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by proxy (Fig. 3b). PRSGxE weighted by GS-GWEIS GxE effect using ISLE significantly improved prediction over PRSD effect alone of depression status mapped by proxy after FDR adjustment (LRT-p = 1.96 × 10−4, FDR-adjusted LRT-p = 2.35 × 10−2).

Discussion

This study performs GWAS and incorporates data on recent adult SLEs into GWEIS of depressive symptoms, identifies new loci and candidate genes for the modulation of genetic response to SLE; and provides insights to help disentangle the underlying aetiological mechanisms increasing the genetic liability through SLE to both depressive symptoms and stress-related traits.

SNP-heritability of depressive symptoms (h2SNP = 9–13%), were slightly higher than previous estimates from African-American populations34, and over a third larger than estimates in MDD from European samples78. h2SNP for PHQ in UKB (9.0%) remained significant after adjusting for SLE (7.9%). Thus, although some genetic contributions may be partially shared between depressive symptoms and reporting of SLE, there is still a relatively large genetic contribution unique to depressive symptoms. Significant h2SNP of DSLE in GS (13%) and TSLEUKB in UKB (4%), which is mainly composed of dependent SLE items, were detected similar to previous studies (8 and 29%)34,42. Conversely, there was no evidence for heritability of independent SLE. A significant bivariate genetic correlation between depressive symptoms and SLE (rG = 0.72) was detected in UKB after adjusting for covariates, suggesting that there are shared common variants underlying self-reported depressive symptoms and SLE. This bivariate genetic correlation was smaller than that estimated from African-American populations (rG = 0.97; p = 0.04; N = 7179)34. Genetic correlations between SLE measures and GHQ were not significant in GS (N = 4919; rG = 1; all p > 0.056), perhaps due to a lack of power in this smaller sample.

Post-GWAS gene-based tests detected six genes significantly associated with PHQ (DCC, ACSS3, DRD2, STAG1, FOXP2 and KYNU). Previous studies have implicated these genes in liability to depression (see Supplementary Table 17), and three of them are genome-wide significant in gene-based tests from the latest meta-analysis of major depression that includes UKB (DCC, p = 2.57 × 10−14; DRD2, p = 5.35 × 10−14; and KYNU, p = 2.38 × 10−6; N = 807,553)79. This supports the implementation of quantitative measures such as PHQ to detect genes underlying lifetime depression status80. For example, significant gene ontology analysis of the UKB-GWAS identified enrichment for positive regulation of long-term synaptic potentiation, and for previous GWAS findings of brain structure81, schizophrenia82 and response to amphetamines83.

The key element of this study was to conduct GWEIS of depressive symptoms and recent SLE. We identified two loci with significant GxE effect in GS. However, none of these associations replicated in UKB (p > 0.05). The strongest association was using TSLE at 53-kb downstream of PIWIL4 (rs12789145). PIWIL4 is brain expressed and involved in chromatin modification84, suggesting it may moderate the effects of stress on depression. It encodes HIWI2, a protein thought to regulate OTX2, that is critical for the development of forebrain and for coordinating critical periods of plasticity disrupting the integration of cortical circuits85,86. Indeed, an intronic SNP in PIWIL4 was identified as the strongest GxE signal in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder using mother’s warmth as environmental exposure87. The other significant GxE identified in our study was in ZCCHC2 using DSLE. This zinc-finger protein is expressed in blood CD4+ T cells and is downregulated in individuals with MDD88 and in those resistant to treatment with citalopram89. No GxE effect was seen using ISLE as exposure.

No significant locus or gene with GxE effect was detected in the UKB-GWEIS. Nevertheless, joint effects (the combined additive main and GxE genetic effects) identified two genes significantly associated with PHQ (ACSS3 and PHF2; see Supplementary Table 17). PHF2 was recently detected as genome-wide significant at the latest meta-analysis of depression79. Notably, PHF2 paralogs have previously been linked with MDD through stress-response in three other studies90–92. Joint effects analyses in GS also detected an additional significant association upstream CYLC2, a gene nominally associated (p < 1 × 10−5) with obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette’s syndrome93. Gene-based test from the GS-GWEIS identified a significant association with MTNR1B, a melatonin receptor gene, using DSLE (both GxE and joint effect; Supplementary Table 17). Genes prioritised using GxE effects were enriched in differentially expressed genes from several tissues including the adrenal gland, which releases cortisol into the blood-stream in response to stress, thus playing a key role in the stress-response system, reinforcing a potential role of GxE in stress-related conditions.

The different instruments and sample sizes available make it hard to compare results between cohorts. Whereas GS contains deeper phenotyping measurements of stress and depressive symptoms than UKB, the sample size is much smaller, which may be reflected in the statistical power required to reliably detect GxE effects. Furthermore, the presence and size of GxE effects are dependent on their parameterisation (i.e., the measurement, scale and distribution of the instruments used to test such interaction)94. Thus, GxE may be incomparable across GWEIS due to differences in both phenotype assessment and stressors tested. Although our results suggest that both depressive symptom measures are correlated with lifetime depression status, different influences on depressive symptoms from the SLE covered across studies may contribute to lack of stronger replication. Instruments in GS cover a wider range of SLE and are more likely to capture changes in depressive symptoms as consequence of their short-term effects. Conversely, UKB could capture more marked long-term effects, as SLE were captured over 2 years compared with the 6 months in GS. New mental health questionnaires covering a wide range of psychiatric symptoms and SLE in the latest release of UKB data provides the opportunity to create similar measures to GS in the near future. Further replication in independent studies with equivalent instruments is required to validate our GWEIS findings. Despite these limitations and a lack of overlap in the individual genes prioritised from the two GWEIS, replication was seen in the predictive improvement of using PRSGxE derived from the GWEIS GxE effects to predict stress-related phenotypes.

The third aim of this study was to test whether modelling GxE effects could improve predictive genetic models, and thus help to explain deviation from additive models and missing heritability for MDD95. Multiple regression models suggested that inclusion of PRSGxE weighted by GxE effects could improve prediction of an individual’s depressive symptoms over use of PRSMDD or PRSD weighted by additive effects alone. In GS, we detected a predictive gain of 19% over PRSMDD weighted by PGC MDD-GWAS, and a gain of 23% over PRSD weighted by UKB-GWAS (Fig. 2a). However, these findings did not surpass stringent Bonferroni correction and could not be validated in UKB. This may reflect in the poor predictive power of the PRS generated from the much smaller GS discovery sample. The results show a noticeably reduced prediction using PRSJoint weighted by joint effects, which suggests that the genetic architecture of stress-response is at least partially independent and differs from genetic additive main effects. Overall, our results from multiple regression models suggest that for polygenic approaches main and GxE effects should be modelled independently.

SLE effects are not limited to mental illness45. Our final aim was to investigate shared aetiology between GxE for depressive symptoms and stress-related traits. Despite the differences between the respondents and non-respondents (Table 1 legend), a significant improvement was seen in predicting depressive status when mapping by proxy cases using GxE effect from GS-GWEIS with independent SLE (FDR-adjusted LRT-p = 0.013), but not with dependent SLE. GxE effects using statistics generated from both discovery samples, despite the differences in measures, nominally improved the phenotypic prediction of schizotypal personality, heart disease and the proxy of COPD (LRT-p < 0.05). Other studies have also found evidence supporting a link between stress and depression in these phenotypes (see Supplementary Material for extended review) and suggest, for instance, potential pleiotropy between schizotypal personality and stress-response. Our findings point to a potential genetic component underlying a stress-response-depression-comorbidities link due, at least in part, to shared stress-response mechanisms. A relationship between SLE, depression and coping strategies such as smoking suggests that genetic stress-response may modulate adaptive behaviours such as smoking, fatty diet intake, alcohol consumption and substance abuse. This is discussed further in the Supplementary Material.

In this study, evidence for SNPs with significant GxE effects came primarily from the analyses of dependent SLE and not from independent SLE. This supports a genetic effect on probability of exposure to, or reporting of SLE, endorsing a gene–environment correlation. Chronic stress may influence cognition, decision making and behaviour eventually leading to higher risk taking96. These conditions may also increase sensitivity to stress among vulnerable individuals, including those with depression, who also have a higher propensity to report SLE, particularly dependent SLE38. A potential reporting bias in dependent SLE may be mediated as well by heritable behavioural, anxiety or psychological traits such as risk taking42,97. Furthermore, individuals vulnerable to MDD may behave in a manner that exposes them more frequently to high risk and stressful environments14. This complex interplay, reflected in the form of a gene–environment correlation effect, would hinder the interpretation of GxE effects from GWEIS as pure interactions. A mediation of associations between SLE and depressive symptoms, through genetically driven sensitivity to stress, personality or behavioural traits would support the possibility of subtle genotype-by-genotype (GxG) interactions, or genotype-by-genotype-by-environment (GxGxE) interactions, contributing to depression98,99. In contrast, PRS prediction of the stress-related traits: schizotypal personality, heart disease and COPD, was primarily from derived weights using independent SLE, suggesting that a common set of variants moderate the effects of SLE across stress-related traits and that larger sample sizes will be required to detect the individual SNPs contributing to this. Thus, our findings support the inclusion of environmental information into GWAS to enhance the detection of relevant genes. The results of studying dependent and independent SLE support a contribution of genetically mediated exposure to and/or reporting of SLE, perhaps through sensitivity to stress as mediator.

This study emphasises the relevance of GxE in depression and human health in general and provides the basis for future lines of research.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

See Supplementary Material: acknowledgements.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

For a full list of MDD working group of the PGC investigators, see the Supplementary Material.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Generation Scotland is a collaboration between the University Medical School and NHS in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow, Scotland, UK

Contributor Information

Aleix Arnau-Soler, Email: aleix.arnau.soler@igmm.ed.ac.uk.

Pippa A. Thomson, Email: Pippa.Thomson@ed.ac.uk

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-018-0360-y).

References

- 1.Plomin R, Owen M, McGuffin P. The genetic basis of complex human behaviors. Science. 1994;264:1733–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.8209254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendler KS, Eaves LJ. Models for the joint effect of genotype and environment on liability to psychiatric illness. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1986;143:279–289. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2007;37:615–626. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colodro-Conde L, et al. A direct test of the diathesis-stress model for depression. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;23:1590–1596. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luciano M, et al. Shared genetic aetiology between cognitive ability and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Generation Scotland’s Scottish family health study. Intelligence. 2010;38:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2010.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2013;34:119–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroud CB, Davila J, Moyer A. The relationship between stress and depression in first onsets versus recurrences: a meta-analytic review. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008;117:206–213. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1998;186:661–669. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silberg J, Rutter M, Neale M, Eaves L. Genetic moderation of environmental risk for depression and anxiety in adolescent girls. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2001;179:116–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendler KS, et al. Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152:833–842. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnau-Soler A, Adams M, Hayward C, Thomson P. Genome-wide interaction study of a proxy for stress-sensitivity and its prediction of major depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnau-Soler, A. et al. A validation of the diathesis-stress model for depression in Generation Scotland. Transl. Psychiatry (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Garantziotis S, Schwartz DA. Ecogenomics of respiratory diseases of public health significance. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2010;31:37–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aschard H, et al. Evidence for large-scale gene-by-smoking interaction effects on pulmonary function. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017;46:894–904. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molfino NA, Coyle AJ. Gene-environment interactions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2008;3:491–497. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polonikov AV, Ivanov VP, Solodilova MA. Genetic variation of genes for xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and risk of bronchial asthma: the importance of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions for disease susceptibility. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;54:440–449. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haiman CA, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han J, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ. Genetic variation in XRCC1, sun exposure, and risk of skin cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;91:1604–1609. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning AK, et al. A genome-wide approach accounting for body mass index identifies genetic variants influencing fasting glycemic traits and insulin resistance. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:659–669. doi: 10.1038/ng.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Murk W, DeWan AT. Genome-wide gene by environment interaction analysis identifies common SNPs at 17q21.2 that are associated with increased body mass index only among asthmatics. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegert S, et al. Genome-wide investigation of gene-environment interactions in colorectal cancer. Hum. Genet. 2013;132:219–231. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong J, et al. Genome-wide interaction analyses between genetic variants and alcohol consumption and smoking for risk of colorectal cancer. PLoS. Genet. 2016;12:e1006296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polfus LM, et al. Genome-wide association study of gene by smoking interactions in coronary artery calcification. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:1041–1049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Risch N, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:444–454. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bleys D, Luyten P, Soenens B, Claes S. Gene-environment interactions between stress and 5-HTTLPR in depression: a meta-analytic update. J. Affect Disord. 2018;226:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peyrot WJ, et al. Does childhood trauma moderate polygenic risk for depression? A meta-analysis of 5765 subjects from the psychiatric genomics consortium. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraft P, Yen YC, Stram DO, Morrison J, Gauderman WJ. Exploiting gene-environment interaction to detect genetic associations. Hum. Hered. 2007;63:111–119. doi: 10.1159/000099183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn EC, et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) and genome-wide by environment interaction study (GWEIS) of depressive symptoms in African American and Hispanic/Latina women. Depress. Anxiety. 2016;33:265–280. doi: 10.1002/da.22484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otowa T, et al. The first pilot genome-wide gene-environment study of depression in the Japanese population. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikeda M, et al. Genome-wide environment interaction between depressive state and stressful life events. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2016;77:e29–e30. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15l10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plomin R, DeFries JC, Loehlin JC. Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1977;84:309–322. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.84.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke, T. et al. Genetic and environmental determinants of stressful life events and their overlap with depression and neuroticism [version 1; referees: 3 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Brugha T, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J. The list of threatening experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychol. Med. 1985;15:189–194. doi: 10.1017/S003329170002105X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. The assessment of dependence in the study of stressful life events: validation using a twin design. Psychol. Med. 1999;29:1455–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798008198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plomin R, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL, McClearn GE, Nesselroade JR. Genetic influence on life events during the last half of the life span. Psychol. Aging. 1990;5:25–30. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.5.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Power RA, et al. Estimating the heritability of reporting stressful life events captured by common genetic variants. Psychol. Med. 2013;43:1965–1971. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bemmels HR, Burt SA, Legrand LN, Iacono WG, McGue M. The heritability of life events: an adolescent twin and adoption study. Twin. Res. Hum. Genet. 2008;11:257–265. doi: 10.1375/twin.11.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boardman JD, Alexander KB, Stallings MC. Stressful life events and depression among adolescent twin pairs. Biodemography Soc. Biol. 2011;57:53–66. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2011.574565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salleh MR. Life event, stress and illness. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2008;15:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thaipisuttikul P, Ittasakul P, Waleeprakhon P, Wisajun P, Jullagate S. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014;10:2097–2103. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S72026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moussavi S, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Topic R, et al. Somatic comorbidity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular risk, and CRP in patients with recurrent depressive disorders. Croat. Med. J. 2013;54:453–459. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2013.54.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lloyd CE, Roy T, Nouwen A, Chauhan AM. Epidemiology of depression in diabetes: international and cross-cultural issues. J. Affect Disord. 2012;142(Suppl):S22–S29. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF. Using chronic pain to predict depressive morbidity in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:39–47. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull. 2014;140:774–815. doi: 10.1037/a0035302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith BH, et al. Cohort profile: Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS). The study, its participants and their potential for genetic research on health and illness. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:689–700. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gunderson, K. L. Whole-genome genotyping on bead arrays. in DNA Microarrays for Biomedical Research: Methods and Protocols (ed. Dufva, M.) 197-213 (Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Kerr SM, et al. Pedigree and genotyping quality analyses of over 10,000 DNA samples from the Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study. Bmc. Med. Genet. 2013;14:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagy R, et al. Exploration of haplotype research consortium imputation for genome-wide association studies in 20,032 Generation Scotland participants. Genome Med. 2017;9:23. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0414-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navrady, L. B. et al. Cohort profile: stratifying resilience and depression longitudinally (STRADL): a questionnaire follow-up of Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 47,13-14g (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Smith BH, et al. Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. Bmc. Med. Genet. 2006;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernandez-Pujals AM, et al. Epidemiology and heritability of major depressive disorder, stratified by age of onset, sex, and illness course in Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang J, et al. Improved imputation of low-frequency and rare variants using the UK10K haplotype reference panel. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8111. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sudlow C, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS. Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Protocol for a large-scale prospective epidemiological resource. UK Biobank (2006)www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/resources/.www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/UK-Biobank-Protocol.pdf.

- 62.UK Biobank Ethics and Governance Framework, Version 3.0. UK Biobank (2007). Ethics and Governance Framework. www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/resources/. www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/EGF20082.pdf

- 63.Brugha TS, Cragg D. The list of threatening experiences: the reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1990;82:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Motrico E, et al. Psychometric properties of the list of threatening experiences--LTE and its association with psychosocial factors and mental disorders according to different scoring methods. J. Affect Disord. 2013;150:931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychol. Med. 1979;9:139–145. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sterling M. General health questionnaire − 28 (GHQ-28) J. Physiother. 2011;57:259. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldberg DP, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol. Med. 1997;27:191–197. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang L, et al. [Value of patient health questionnaires (PHQ)−9 and PHQ-2 for screening depression disorders in cardiovascular outpatients] Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing. Za Zhi. 2015;43:428–−431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith DJ, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of probable major depression and bipolar disorder within UK biobank: cross-sectional study of 172,751 participants. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu JZ, Erlich Y, Pickrell JK. Case-control association mapping by proxy using family history of disease. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:325–331. doi: 10.1038/ng.3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Almli LM, et al. Correcting systematic inflation in genetic association tests that consider interaction effects: application to a genome-wide association study of posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1392–1399. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keller MC. Gene x environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: the problem and the (simple) solution. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;75:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. FUMA: functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Euesden J, Lewis CM, O’Reilly PF. PRSice: polygenic risk score software. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1466–1468. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics et al. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat. Genet. 45, 984–994 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Commun. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Altman DG, Royston P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ. 2006;332:1080. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stein JL, et al. Voxelwise genome-wide association study (vGWAS) Neuroimage. 2010;53:1160–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li Z, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 30 new susceptibility loci for schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1576–1583. doi: 10.1038/ng.3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hart AB, et al. Genome-wide association study of d-amphetamine response in healthy volunteers identifies putative associations, including cadherin 13 (CDH13) PLoS One. 2012;7:e42646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sugimoto K, et al. The induction of H3K9 methylation by PIWIL4 at the p16Ink4a locus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;359:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sivagurunathan S, Arunachalam JP, Chidambaram S. PIWI-like protein, HIWI2 is aberrantly expressed in retinoblastoma cells and affects cell-cycle potentially through OTX2. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2017;22:17. doi: 10.1186/s11658-017-0048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee HHC, et al. Genetic Otx2 mis-localization delays critical period plasticity across brain regions. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:680–688. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sonuga-Barke EJ, et al. Does parental expressed emotion moderate genetic effects in ADHD? An exploration using a genome wide association scan. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008;147B:1359–1368. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Belzeaux R, et al. Responder and nonresponder patients exhibit different peripheral transcriptional signatures during major depressive episode. Transl. Psychiatry. 2012;2:e185. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mamdani F, Berlim MT, Beaulieu MM, Turecki G. Pharmacogenomic predictors of citalopram treatment outcome in major depressive disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;15:135–144. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.766762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wong ML, et al. The PHF21B gene is associated with major depression and modulates the stress response. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:1015–1025. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Walsh RM, et al. Phf8 loss confers resistance to depression-like and anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15142. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shi G, et al. PHD finger protein 2 (PHF2) represses ribosomal RNA gene transcription by antagonizing PHF finger protein 8 (PHF8) and recruiting methyltransferase SUV39H1. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:29691–29700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.571653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yu D, et al. Cross-disorder genome-wide analyses suggest a complex genetic relationship between Tourette’s syndrome and OCD. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2015;172:82–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eaves LJ, Last K, Martin NG, Jinks JL. A progressive approach to non-additivity and genotype-environmental covariance in the analysis of human differences. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1977;30:1–42. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1977.tb00722.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Polderman TJ, et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:702–709. doi: 10.1038/ng.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ceccato S, Kudielka BM, Schwieren C. Increased risk taking in relation to chronic stress in adults. Front. Psychol. 2015;6:2036. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kandler C, Bleidorn W, Riemann R, Angleitner A, Spinath FM. Life events as environmental states and genetic traits and the role of personality: a longitudinal twin study. Behav. Genet. 2012;42:57–72. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9491-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Conway CC, Hammen C, Brennan PA, Lind PA, Najman JM. Interaction of chronic stress with serotonin transporter and catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms in predicting youth depression. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:737–745. doi: 10.1002/da.20715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Genetic moderation of child maltreatment effects on depression and internalizing symptoms by serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1) genes in African American children. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014;26:1219–1239. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.