Abstract

Natural methane emissions are noticeably influenced by warming of cold arctic ecosystems and permafrost. An evaluation specifically of Arctic natural methane emissions in relation to our ability to mitigate anthropogenic methane emissions is needed. Here we use empirical scenarios of increases in natural emissions together with maximum technically feasible reductions in anthropogenic emissions to evaluate their potential influence on future atmospheric methane concentrations and associated radiative forcing (RF). The largest amplification of natural emissions yields up to 42% higher atmospheric methane concentrations by the year 2100 compared with no change in natural emissions. The most likely scenarios are lower than this, while anthropogenic emission reductions may have a much greater yielding effect, with the potential of halving atmospheric methane concentrations by 2100 compared to when anthropogenic emissions continue to increase as in a business-as-usual case. In a broader perspective, it is shown that man-made emissions can be reduced sufficiently to limit methane-caused climate warming by 2100 even in the case of an uncontrolled natural Arctic methane emission feedback, but this requires a committed, global effort towards maximum feasible reductions.

Introduction

Future concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere will determine the degree of warming the Earth will experience. Atmospheric methane, a powerful GHG, is controlled primarily by its anthropogenic and natural emissions and its destruction in the atmosphere. Methane is released into the atmosphere through a number of natural sources including wetlands, rivers and lakes, permafrost, wild animals, wildfires, termites, geological sources, and marine sources1. While significant uncertainty exists in the estimates of emissions from each of these sources, the relative order of magnitude of total global natural emissions has remained robust. This is despite discrepancies between top-down (atmospheric) and bottom-up measurement-based estimates – derived by adding estimates of individual natural methane-generating processes2. The rapid warming of the Arctic makes it plausible that natural emissions will increase in this area2,3 but the question remains whether these increases will be so large that they cannot be offset by reductions in anthropogenic emissions. To estimate the impact of future potential increases in natural methane emissions in the context of maximum technically feasible reductions in anthropogenic emissions, a modeling exercise was undertaken for this study, using an estimate of 202 Tg (±28 Tg) CH4/year1 for current global natural methane emissions. While on the lower side, this estimate lies within the range of estimates of total natural emissions (194–296 Tg CH4/yr) constrained by top-down approaches1 that take into account changes in atmospheric methane burden and methane’s lifetime in the atmosphere.

As for the Arctic itself, different assessments have recently summarized the current understanding concerning the processes that generate, consume, store and release methane in high latitude terrestrial and marine systems2,4, based on flux measurements, process studies, model simulations, and estimates of carbon stores. These show that both the terrestrial and marine Arctic regions are sources of methane5, although their current estimated magnitudes and future projections vary strongly.

For Arctic terrestrial systems, it is clear that the tundra region, inclusive of wetland areas, represents the major natural source of methane. Current estimates of natural methane emissions from Arctic tundra fall in the range of 11–39 Tg CH4 per year5. Our ability to constrain this estimate is limited by key uncertainties, primarily the limited measurements in time (few long-term records, and very limited measurements during the winter season) and in spatial coverage (very few measurement sites and most are located at “practical” rather than representative locations). Other limitations relate to gaps in understanding the biological and physical processes that control a release of methane from these ecosystems to the atmosphere. In addition to the terrestrial wetland emissions, the freshwaters of the Arctic are estimated to contribute as much as 13–16 Tg CH4/year6, yielding total terrestrial emissions in the range of 24–55 Tg CH4 per year i.e. about 10–25% of global natural emissions. Table 1 provides a summary of estimates for current Arctic natural methane emission sources.

Table 1.

| Tg CH4/yr | Range | Best estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arctic Terrestrial | Tundra | 11 to 39 | 25 |

| Lakes | 13 to 16 | 15 | |

| Arctic Marine | Sub-sea permafrost | 1 to 17 | 5 |

| Sea ice leads | Not quantified | ||

| Total Arctic | 25 to 72 | Ca 45 | |

| Total global natural emissions | 202 |

Future methane releases from Arctic tundra depend on how changes in Arctic temperatures and precipitation affect these controlling processes (leading to a change in methane production or consumption), physical changes (permafrost thaw, thermokarst) as well as the extent/magnitude of available carbon pools in Arctic soils. It is estimated that 1400–1850 Pg of carbon is frozen in Arctic soils7–9. Since there is significant uncertainty in these estimates10, the potential release of this permafrost carbon to the atmosphere is also uncertain. The quantification of this uncertainty is further exacerbated due to the limited (or non-existent) representation of carbon and other biogeochemical cycle processes unique to the Arctic region and methane in Earth system models11. Nevertheless, it is well recognized that significant stocks of frozen carbon exist in permafrost with the potential to thaw and decay, thus releasing methane and/or carbon dioxide as the Arctic continues to warm12.

For Arctic marine systems, gas hydrates represent the largest potential source of marine methane release to the atmosphere due to the large amounts of methane contained within these deposits11. Even so, many other source types (e.g. geological) contribute to a potential release of methane from the ocean. Current emissions from the Arctic Ocean into the atmosphere are estimated to range from 1 to as high as 17 Tg CH4/year13–15. These emissions emanate primarily from shallow waters of the Arctic Ocean, since methane released from the deeper seabed is subject to significant oxidation during its ascent through the water column1. Future methane release from the ocean depends on the methane stocks in marine reservoirs but also on the impact of changing temperatures and sea ice coverage on the controlling biological and physical processes2.

A recent estimate put the quantity of carbon frozen in gas hydrates at 116 Pg11. This is the basis for estimating a potential increase by 1.9 Tg per year in the release of methane into the Arctic Ocean over the next 100 years1, which translates into an even smaller release to the atmosphere due to oxidative loss while methane rises through the water column. Overall, this is a relatively small additional contribution. However, this conclusion is tempered by significant uncertainty in the magnitude of marine hydrate carbon that is potentially vulnerable, and how much methane may pass the water column to the atmosphere, while observations that can act as a benchmark are severely lacking.

Regardless of the limitations and uncertainties in characterizing Arctic natural (terrestrial and marine) methane emissions, their impact on global and Arctic climate has the potential to be significant and needs to be quantified. The future emission values presented in Fig. 1 represent four scenarios judged to characterize the range of possible future outcomes for changes in Arctic natural methane emissions (and their different combinations). The four scenarios used to estimate the climate response to changes in natural methane emissions are described as no change (+0 Tg CH4/year), a low (+50 Tg CH4/year), a high (+100 Tg CH4/year), and an extreme (+150 Tg CH4/year) increase by 2100 above the 202 Tg CH4/year global natural emissions baseline16. We use a one box model of atmospheric methane and radiative forcing calculations to calculate impacts of future changes in methane emissions, both from anthropogenic and from natural sources, on concentrations of atmospheric methane and global climate forcing (Fig. 1, Table 2). This one box model describes the change in burden of atmospheric methane as a balance of natural and anthropogenic emissions, and the atmospheric and surface sinks (see Methods). It also models methane’s lifetime in the atmosphere as a function of its atmospheric concentration.

Figure 1.

Arctic methane generator. Generic scenarios of change in natural arctic methane emissions. Scenarios I–IV are used in the box-model calculations of atmospheric concentration change pathways.

Table 2.

Global radiative forcing (with respect to pre-industrial) and atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases with the baseline and scenarios for methane change described in this paper.

| CLE | MFR | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1750 | 2011 | 2100 | ||||||||

| Scenario | I | II | III | IV | I | II | III | IV | |||

| CH4 | RF W/m2 | — | 0.61 | 1.00 | 1.07 | 1.15 | 1.21 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.70 |

| ppb | 722 | 1803 | 2842 | 3060 | 3284 | 3511 | 1423 | 1616 | 1816 | 2021 | |

| CO2 | RF W/m2 | — | 1.83 | 4.87 | 4.87 | 4.87 | 4.87 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 |

| ppm | 278 | 391 | 670 | 670 | 670 | 670 | 421 | 421 | 421 | 421 | |

| Changed CH4 forcing with respect to CLE/scenario I | % | 7 | 14 | 21 | −58 | −48 | −39 | −30 | |||

All RF values (also the ones for 2011) were calculated with the equations of Etminan et al.29.

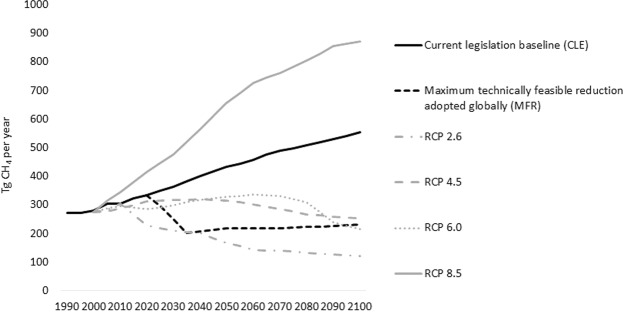

The anthropogenic methane emissions used here are updated versions of global GAINS model scenarios17–19 describing a current legislation (CLE) and a maximum technically feasible reduction (MFR) scenario2. The CLE scenario assumes no further abatement of emissions than prescribed in already adopted legislation, while the MFR scenario assumes maximum feasible implementation of existing abatement technology without considering effects of future technological development. Both scenarios fall within the ranges of the Representative Concentration Pathways20 (RCPs) of IPCC’s fifth assessment report21. For the period from 2005 to 2050 for which the GAINS model is defined, the updated CLE and MFR scenarios use macroeconomic and energy system drivers consistent with the IEA World Energy Outlook New Policy Scenario 201722. For the period from 2050 to 2100, growth in activity levels for the CLE and MFR scenarios, respectively, are consistent with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways scenarios SSP3 6.0 and SSP3 2.623. For further details, see the Methods section. Figure 2 shows global anthropogenic methane emissions (excluding emissions from forest and grassland fires) over the 1990–2100 period in the CLE and MFR scenarios and in comparison with emissions for the RCP scenarios.

Figure 2.

Global anthropogenic methane emissions 1990–2100 in GAINS and in the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs)20,37.

Within the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP, amap.no), which is one of the permanent scientific Working Groups under the Arctic Council, a multi-model study was conducted to isolate the effects of maximum feasible technical reductions in anthropogenic methane emissions on Arctic climate24. Three state-of-the-art Earth System Models were used, namely the Canadian Earth System Model CanESM225, the Norwegian Earth System Model26 (NorESM), and the Community Earth System Model CESM1-CAM5 developed at NCAR, USA27, based on CLE and MFR emission scenarios from the GAINS model extending to 2050. The model results indicated that global implementation of maximum technically feasible reductions in anthropogenic methane is able to reduce the future average global climate warming by around 0.1–0.2 °C for the 2036–2050 period (including corresponding contributions from ozone and stratospheric water vapor), relative to a case with continuously increasing emissions according to the CLE scenario2. These results from Gauss et al.24 also showed that a reduction in anthropogenic methane emissions can provide a significant contribution to achieve the target of the Paris agreement, which aims to keep global warming toward the end of this century well below 2.0 °C, preferably 1.5 °C, compared to the pre-industrial level. For the Arctic region, these Earth system model results showed even larger magnitudes of reduced warming related to maximum feasible reduction in anthropogenic methane emissions (due to Arctic amplification), but also larger variability28. The results reported in that earlier study were based on atmospheric methane concentration changes obtained from the same one-box model of atmospheric methane that is used here. However, the Earth system model calculations in Gauss et al.24 did not consider changes in natural methane emissions and the results were analyzed only up to year 2050. Here, we use the one box model of atmospheric methane, extended to 2100, and based on the updated anthropogenic emissions for the MFR and CLE scenarios.

Arctic warming driven by all climate forcers, primarily carbon dioxide, can potentially increase natural emissions from terrestrial and marine ecosystems. In contrast, the maximum technically feasible (MFR) emission reduction from the eight Arctic Council member states alone reduces anthropogenic emissions by 142 Tg CH4/year by 2100 in the MFR scenario (Fig. 2), which is considerably higher than the magnitude of the potential increase by 50 Tg CH4/year in natural emissions due to climate warming in the low scenario but comparable in size to the increase by 150 Tg CH4/yr in our extreme natural emission change scenario IV.

Figure 3 shows the resulting changes in atmospheric methane concentration obtained from the one box model for the MFR and CLE scenarios together with the corresponding four scenarios for changes in natural methane emissions. As Earth system models progressively include methane-related biogeochemical processes it will be possible to gain a better understanding of the effect of climate warming on methane-related feedbacks and quantify the effect of mitigation of anthropogenic methane emissions in a consistent framework. Here we use the changes in atmospheric methane concentration from Fig. 3 to calculate global-mean radiative forcing (RF) for the year 2100 for the eight different combinations of changes in anthropogenic and natural emissions, using formulae from Etminan et al.29. The results for RF, along with the concentrations used, are listed in Table 2. All CH4 RFs in the MFR case (0.42 to 0.70 W/m2) are smaller than the lowest CH4 RF in the CLE case (1.00 W/m2), since the maximum feasible reduction in global anthropogenic emissions overwhelms the natural emissions increase even in the extreme Scenario IV. The maximum increase in naturally-induced CH4 RF in the CLE case is 0.21 W/m2 (“CLE + natural emissions scenario IV” minus “CLE + natural emissions scenario I”), while in the MFR case it is 0.28 W/m2. The slightly higher value in the MFR case is due to lower CH4 concentrations (less saturation in the CH4 absorption bands) and lower N2O concentrations in the MFR case.

Figure 3.

Box model results. Current legislation emission (CLE) and maximum feasible reduction (MFR) scenarios for anthropogenic impact on atmospheric methane concentrations towards 2100. The natural emission scenarios are from Fig. 1(I–IV). Each additional 50 Tg CH4/yr increase in natural emissions over the 2006–2100 period increase CH4 concentration in 2100 by about 200 ppb. But CH4 concentration in 2100 is reduced by about 1400–1500 ppb in response to going from CLE to MFR.

None of the naturally-induced CH4 RF increases are as large in magnitude as the decrease in CH4 RF range that is due to a reduction in anthropogenic emissions, represented by the differences between the CLE and MFR cases. The smallest decrease in CH4 RF attributable to a reduction in anthropogenic emissions is 0.51 W/m2 (‘CLE/Scenario IV’ minus ‘MFR/Scenario IV’) while the largest decrease is 0.58 W/m2 (‘CLE/Scenario I’ minus ‘MFR/Scenario I’). Also, it has to be said that in the MFR case (featuring reductions in GHG global mean concentrations), methane-caused warming in the Arctic will be lower compared to the CLE, which would make the extreme scenario IV relatively less likely than in the CLE case.

In conclusion, although sizeable for the impact on methane forcing alone, and approaching the scale of for example the cooling effect of sulphate aerosols in the atmosphere30, the feedback from natural methane emission changes in the Arctic remains minor compared to the effect of (global) anthropogenic emission cuts that could occur in a MFR-type scenario.

The scenarios used in this study cover a wide range of future emissions, up to an extreme scenario where the Arctic would emit an additional 150 Tg CH4/yr by 2100. Considering that this number is roughly equal to ~75% of current global natural emissions, such an increase appears unlikely. One of the few possible causes for such a large increase would be the widespread destabilization of gas hydrates, but recent model studies and observations indicate that this source is lower and more stable than previously thought11,31, and the geological record shows little evidence of large releases of methane from gas hydrates in the past2,32. However, terrestrial sources may increase strongly with continued warming, and Arctic climate feedbacks are not limited to methane alone. The combined release of methane and CO2 from the northern permafrost region represents a sustained source that can accelerate climate change33, while sea ice decline, snow cover loss and shrub expansion further amplify warming through a lowering of surface albedo13. The cumulative effect of climate change on the terrestrial and marine Arctic, and the potential for positive feedbacks that affect the rest of the world, remains a topic of high concern. Methane, however, is too often portrayed as solely being able to cause runaway climate change. Despite large uncertainties associated with future projections of Arctic natural methane emissions, our current best estimates of potential increases in natural emissions remain lower than anthropogenic emissions. In other words, claims of an apocalypse associated solely with Arctic natural methane emission feedbacks are misleading, since they guide attention away from the fact that the direction of atmospheric methane concentrations, and their effect on climate, largely remain the responsibility of anthropogenic GHG emissions.

A rise in natural methane emissions may make it more challenging to reach the goals set by the Paris agreement, but they should not be a cause for indifference. On the contrary, the possibility for natural climate feedbacks emphasizes the need for a committed and strong reduction in anthropogenic GHG emissions starting sooner rather than later to avoid dangerous climate change.

Methods

Box model calculations: One-box model of atmospheric CH4

A one-box model of atmospheric CH4 is used to obtain globally-averaged CH4 concentrations, [CH4], corresponding to global emissions for the CLE and the MFR scenarios. The model describes the change in burden of atmospheric CH4 (H) as a balance of surface emissions (E = EN + EA, consisting of natural EN and anthropogenic emissions EA) and the atmospheric and surface sinks (S).

| 1 |

The sink S is calculated as a first-order loss process from methane’s atmospheric lifetime in the atmosphere () as . is calculated as

| 2 |

where τOH (present day value of 11.17 years), τstrat (120 years), τtrop−Cl (200 years) and τsoil (150 years) are the lifetimes associated with the destruction of CH4 by tropospheric OH radicals, loss in the stratosphere, reaction with tropospheric chlorine and uptake by soils, respectively, following Prather et al.16 which yields a present day value of as 9.1 ± 0.9 years in equation (2). For the pre-industrial period, Prather et al.16 estimate as 9.5 ± 1.3 years assuming τOH to be equal to 11.76 years (based on Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP) results34 and lifetimes associated with other processes to stay the same. In our study, the value of for the future period is calculated by changing τOH based on changes in [CH4] but τstrat, τtrop−Cl and τsoil are assumed to stay the same. For τOH we follow the approach used in the MAGICC IAM (http://wiki.magicc.org/index.php?title=Non-CO2_Concentrations) and by Prather et al.16 which results in a decrease in loss frequency by 0.32%, and hence an increase in methane’s lifetime, for every 1% increase in [CH4]. This is implemented as shown in equation (3)

| 3 |

which is used to determine methane life time associated with the destruction of CH4 by tropospheric OH radicals for the next time step, τOH(t + 1), given atmospheric methane concentrations for the current and next time steps, [CH4](t) and [CH4](t + 1), and methane life time associated with OH for the current time step, τOH(t). For the present day the value is 11.17 years and a 1% increase in [CH4] implies increases to about 11.21 years. This approach takes into account the positive feedback where [CH4] affects its own lifetime but the effects of changes in NOx emissions or tropospheric water vapour are not taken into account.

The one-box model of atmospheric methane is first evaluated over the historical period to investigate if it reproduces the observation-based estimates of anthropogenic emissions given the historical rate of increase of atmospheric methane burden, and Prather et al.’s16 estimates of natural emissions and methane lifetime based on various processes associated with equation (2). After successful evaluation of the one-box model of atmospheric methane over the historical period, the model is then applied in a forward mode where given the emissions from the CLE and MFR scenarios, and the empirical scenarios of increase in natural emissions, it finds future concentrations of atmospheric methane. These results are shown and discussed in detail in the Supplementary Information.

The following scenarios I–IV described in the text are used to estimate increases in natural emissions:

0 Tg CH4/yr increase over 2006–2100 period (scenario I)

50 Tg CH4/yr increase over 2006–2100 period (scenario II)

100 Tg CH4/yr increase over 2006–2100 period (scenario III)

150 Tg CH4/yr increase over 2006–2100 period (scenario IV).

Anthropogenic emission scenarios

The anthropogenic methane emissions used here are updated versions of previously published global GAINS model scenarios17,35 and include recent revisions to emission estimates and abatement potentials in the oil and gas sectors18 and the waste and wastewater sectors36. The scenarios of the GAINS model describe a current legislation (CLE) and a maximum technically feasible reduction (MFR) scenario, with the scope for future abatement with existing technology forming the difference in emissions between the two scenarios. For the period 2005–2050, the updated CLE and MFR scenarios use macroeconomic and energy system drivers consistent with the IEA World Energy Outlook New Policy Scenario 201722. These take account of effects on activity levels from existing as well as announced policies, including effects of the National Determined Contributions (NDCs) made by countries for the Paris Agreement. For the period 2050 to 2100, the growth in activity drivers has been taken from the database on Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs)23. We find that the SSP3 “Regional rivalry” scenario corresponds the closest to the macroeconomic and population assumptions of IEA-WEO 2017 for the period leading up to 2050. The SSP3 is therefore chosen as starting point for an extension of activity levels to 2100. The drivers of the CLE scenario for 2050 to 2100 are consistent with the growth in activity levels of the SSP3 6.0, while the MFR scenario uses drivers consistent with the SSP3 2.6, which assumes lower consumption of fossil fuels. In addition to activity data changes, the MFR scenario assumes full implementation of maximum technically feasible reduction in methane emissions in the long-run. The CLE and MFR scenarios fall within the ranges of the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) of IPCC’s fifth assessment report20. Methane emissions in the CLE scenario are lower than in the RCP 8.5, primarily because of more optimistic assumptions about transformations of the energy sector embedded in the IEA energy scenario used here for the period pre-2050. In contrast to the RCP scenarios, which include effects of technological development, the MFR scenario only considers abatement potentials from existing technology. This constrains the maximum abatement potential in the MFR scenario in the long-term.

Radiative forcing

Values of radiative forcing (RF) for CH4 and CO2 were calculated with equations from Etminan et al.29 (their Table 1). Due to overlapping absorption, the RFs of CH4 and CO2 depend on their own concentrations but also on that of N2O. The RF equations require as input the reference (e.g. year 1750) and perturbed (e.g. year 2100) concentrations of CH4, CO2 and N2O. Concentrations of CO2 and N2O were taken from those RCP scenarios that are consistent with our GAINS anthropogenic emission scenarios, i.e. RCP 2.6 for MFR and RCP 6.0 for CLE20. CH4 concentrations are calculated using our one-box model of atmospheric CH4, which incorporates the whole range of maximum feasible reduction in methane emissions and also takes into account our estimates of natural emission changes.

It is important to note that in this study we have only calculated the direct RF of CH4 concentration change. We did not consider the indirect effects of ozone and stratospheric water vapor that would result from an increase in methane emissions. Myhre et al.30 accounted for the ozone and stratospheric water vapour contributions by multiplying the effect of CH4 by 1.50 and 1.15, respectively, but these scaling factors strictly apply to the pre-industrial to present-day period only. Calculating indirect effects for our future scenarios would require more advanced modelling tools but their consideration would not change the conclusions of the study, as they would increase the anthropogenic and natural contributions to methane RF by similar percentage amounts.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the support of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment (AMAP) programme for the assessment processes that initiated the work leading to the analyses presented. TRC was supported by the Danish Ministry of Energy, Utilities and Climate. FJWP was supported by the Norwegian Research Council under grant agreement 274711, and the Swedish Research Council under registration nr. 2017-05268.

Author Contributions

T.R.C. and F.J.W.P. developed the natural emission scenarios and wrote the manuscript. V.K.A. did the box model work, M.G. the radiative forcing calculations and L.H.I. the updated anthropogenic emission scenarios. All authors contributed to the writing.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-37719-9.

References

- 1.Saunois M, et al. The global methane budget 2000–2012. Earth System Science Data. 2016;8:697–751. doi: 10.5194/essd-8-697-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AMAP. AMAP Assessment2015: Methane as an Arctic climate forcer. Report No. 978-82-7971-091-2, vii–139 pp. (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme(AMAP), Oslo, Norway, 2015).

- 3.McGuire AD, et al. An assessment of the carbon balance of Arctic tundra: comparisons among observations, process models, and atmospheric inversions. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:3185–3204. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-3185-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stocker, T. F. et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- 5.Parmentier F-JW, et al. A synthesis of the arctic terrestrial and marine carbon cycles under pressure from a dwindling cryosphere. Ambio. 2017;46:53–69. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wik M, Thornton BF, Bastviken D, Uhlbäck J, Crill PM. Biased sampling of methane release from northern lakes: A problem for extrapolation. Geophysical Research Letters. 2016;43:1256–1262. doi: 10.1002/2015GL066501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuur EAG, et al. Vulnerability of permafrost carbon to climate change: Implications for the global carbon cycle. Bioscience. 2008;58:701–714. doi: 10.1641/B580807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire AD, et al. Sensitivity of the carbon cycle in the Arctic to climate change. Ecological Monographs. 2009;79:523–555. doi: 10.1890/08-2025.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hugelius G, et al. Estimated stocks of circumpolar permafrost carbon with quantified uncertainty ranges and identified data gaps. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:6573–6593. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-6573-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen, T. et al. In Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA) (ed. AMAP) (AMAP, 2017).

- 11.Kretschmer K, Biastoch A, Rüpke L, Burwicz E. Modeling the fate of methane hydrates under global warming. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2015;29:610–625. doi: 10.1002/2014GB005011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knoblauch, C., Beer, C., Liebner, S., Grigoriev, M. N. & Pfeiffer, E.-M. Methane production as key to the greenhouse gas budget of thawing permafrost. Nature Climate Change, 1, 10.1038/s41558-018-0095-z (2018).

- 13.Kort EA, et al. Atmospheric observations of Arctic Ocean methane emissions up to 82 degrees north. Nature Geoscience. 2012;5:318–321. doi: 10.1038/NGEO1452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shakhova N, et al. Ebullition and storm-induced methane release from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Nature Geoscience. 2014;7:64–70. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vancoppenolle M, et al. Role of sea ice in global biogeochemical cycles: emerging views and challenges. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2013;79:207–230. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prather MJ, Holmes CD, Hsu J. Reactive greenhouse gas scenarios: Systematic exploration of uncertainties and the role of atmospheric chemistry. Geophysical Research Letters. 2012;39:L09803–n/a. doi: 10.1029/2012GL051440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoglund-Isaksson L. Global anthropogenic methane emissions 2005-2030: technical mitigation potentials and costs. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2012;12:9079–9096. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-9079-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoglund-Isaksson, L. Bottom-up simulations of methane and ethane emissions from global oil and gas systems 1980 to 2012. Environmental Research Letters 12, 10.1088/1748-9326/aa583e (2017).

- 19.Stohl A, et al. Evaluating the climate and air quality impacts of short-lived pollutants. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2015;15:10529–10566. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-10529-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meinshausen M, et al. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Climatic Change. 2011;109:213–241. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0156-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IPCC. Climate Change2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- 22.OECD. & International Energy Agency. World energy outlook. (OECD).

- 23.van Vuuren DP, et al. The Shared Socio-economicPathways: Trajectories for human development and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change. 2017;42:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauss, M. et al. Modeling the Climate Response to methane. In: Methane as an Arctic Climate Forcer (ed. AMAP) (2015).

- 25.Arora, V. K. et al. Carbon emission limits required to satisfy future representative concentration pathways of greenhouse gases. Geophysical Research Letters38, 10.1029/2010gl046270 (2011).

- 26.Bentsen M, et al. The Norwegian Earth System Model, NorESM1-M - Part 1: Description and basic evaluation of the physical climate. Geoscientific Model Development. 2013;6:687–720. doi: 10.5194/gmd-6-687-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR community atmosphere model (CAM5.0). (2012).

- 28.AMAP. Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in theArctic (SWIPA) 2017. Report No. 978-82-7971-101-8, xiv–269 pp. (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway, 2017).

- 29.Etminan M, Myhre G, Highwood EJ, Shine KP. Radiative forcing of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide: A significant revision of the methane radiative forcing. Geophysical Research Letters. 2016;43:12614–12623. doi: 10.1002/2016gl071930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myhre, G., et al. Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In: Stocker, T.F., et al., Eds., Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2013).

- 31.Berchet A, et al. Atmospheric constraints on the methane emissions from the East Siberian Shelf. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2016;16:4147–4157. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-4147-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sowers T. Late Quaternary Atmospheric CH4 Isotope Record Suggests Marine Clathrates Are Stable. Science. 2006;311:838–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1121235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuur EAG, et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature. 2015;520:171–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voulgarakis A, et al. Analysis of present day and future OH and methane lifetime in the ACCMIP simulations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2013;13:2563–2587. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-2563-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosetti V, Carraro C, Tavoni M. Climate change mitigation strategies in fast-growing countries: The benefits of early action. Energ Econ. 2009;31:S144–S151. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2009.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomez-Sanabria A, Höglund-Isaksson L, Rafaj P, Schöpp W. Carbon in global waste and wastewater flows –its potential as energy source under alternative future waste management regimes. Advances in Geosciences. 2018;45:105–113. doi: 10.5194/adgeo-45-105-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.RCP database version 2.0.5, (ed. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis), (http://tntcat.iiasa.ac.at/RcpDb/dsd?Action=htmlpage&page=download, 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.