Abstract

This study aimed at characterizing herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) epidemiology in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). HSV-1 records were systematically reviewed. Findings were reported following the PRISMA guidelines. Random-effects meta-analyses were implemented to estimate pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence. Random-effects meta-regressions were conducted to identify predictors of higher seroprevalence. Thirty-nine overall seroprevalence measures yielding 85 stratified measures were identified and included in the analyses. Pooled mean seroprevalence was 65.2% (95% CI: 53.6–76.1%) in children, and 91.5% (95% CI: 89.4–93.5%) in adults. By age group, seroprevalence was lowest at 60.5% (95% CI: 48.1–72.3%) in <10 years old, followed by 85.6% (95% CI: 80.5–90.1%) in 10–19 years old, 90.7% (95% CI: 84.7–95.5%) in 20–29 years old, and 94.3% (95% CI: 89.5–97.9%) in ≥30 years old. Age was the strongest predictor of seroprevalence explaining 44.3% of the variation. Assay type, sex, population type, year of data collection, year of publication, sample size, and sampling method were not significantly associated with seroprevalence. The a priori considered factors explained 48.6% of the variation in seroprevalence. HSV-1 seroprevalence persists at high levels in MENA with most infections acquired in childhood. There is no evidence for declines in seroprevalence despite improving socio-economic conditions.

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a widespread and incurable infection1,2. Although this infection is usually asymptomatic3, the virus is shed frequently and subclinically4,5. Clinically-apparent HSV-1 infection most often manifests as orolabial herpes lesions6,7, but the virus causes a diverse spectrum of diseases including neonatal herpes, corneal blindness, herpetic whitlow, meningitis, encephalitis, and genital herpes7,8. The infection’s clinical manifestations depend on the virus’ initial acquisition portal6,7—oral-to-oral transmission leads to an oral infection6,7, and oral-to-genital transmission (through oral sex) leads to a genital infection6,9,10.

HSV-1 is endemic globally as indicated by the high HSV-1 antibody prevalence (seroprevalence) across regions2,11,12. Although HSV-1 is typically acquired in childhood8, changes in hygiene and socio-economic conditions appear to have reduced exposure during childhood in Western11,13–20 and Asian countries21. A large fraction of youth in these countries reach sexual debut with no protective antibodies against HSV-1 infection, and thus at risk of acquiring the infection genitally6,22. A growing evidence indicates that HSV-1 is overtaking HSV-2 as the leading cause of first episode genital herpes in Western6,22–26 and (apparently) Asian countries21. The extent to which such a transition in HSV-1 epidemiology is occurring in other global regions remains unknown.

In this context, we aspired to determine HSV-1 seroprevalence levels in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and to characterize the extent to which HSV-1 is the etiological cause of clinically-diagnosed genital ulcer disease (GUD) and clinically-diagnosed genital herpes. These aims were addressed by: (1) systematically reviewing and synthesizing available data on HSV-1 seroprevalence and HSV-1 viral detection in GUD and genital herpes, (2) estimating the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence in different populations and across ages, and (3) assessing the associations and predictors of higher seroprevalence and sources of between-study heterogeneity.

This study is part of a series of ongoing investigations meant to inform efforts by the World Health Organization (WHO) and global partners to characterize the regional and global infection and disease burden of HSV infections, accelerate HSV vaccine development27,28, and explore optimal strategies for HSV-1 control.

Methods

The methodology used in this study follows and adapts that used in a systematic review of HSV-1 seroprevalence and HSV-1 viral detection in GUD and genital herpes in Asia21.

Data sources and search strategy

The present systematic review was informed by the Cochrane Collaboration handbook29, and was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines30. The PRISMA checklist can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

A systematic literature search was conducted up to October 8, 2017, in PubMed and Embase. The search criteria included exploded MeSH/Emtree terms to cover all subheadings, with no language or time restrictions. Another search was conducted up to December 1, 2017 in national and regional databases including: Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Iraqi Academic Scientific Journals Database, Scientific Information Database of Iran, and PakMediNet of Pakistan. Search strategies can be found in Supplementary Box S1.

The MENA region definition included 23 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen.

Study selection and inclusion and exclusion criteria

Search results were imported into Endnote, where duplicate records were removed. Titles and abstracts of remaining records were screened independently by SC, MH, and HC, for relevance. Full texts of records deemed relevant or potentially relevant were retrieved for further screening. Bibliographies of relevant records and reviews were also screened for possible missing publications.

The inclusion criteria included any record reporting an HSV-1 seroprevalence measure, based on primary data and type-specific diagnostic assay such as glycoprotein-G-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA).

The inclusion criteria also included any record reporting a proportion of HSV-1 viral detection in clinically-diagnosed GUD or in clinically-diagnosed genital herpes. The minimum sample size of included studies was 10, regardless of the outcome measure.

The exclusion criteria included case reports, case series, reviews, editorials, letters to editors, commentaries, qualitative studies, and animal studies. HSV-1 seroprevalence measures reported in <3 months-old infants were excluded since they may reflect maternal antibodies.

In this work, a “record” refers to a document (a publication) reporting an outcome measure of interest, while a “study” refers to the details pertaining to a specific outcome measure. Accordingly, one record may contribute multiple studies, and multiple records of the same study are considered as duplicates and only included once.

Data extraction and data synthesis

The extracted information included: author(s), publication title, year(s) of data collection, publication year, country of origin, country of survey, city, study site, study design, study sampling procedure, study population and its characteristics (e.g., sex and age), sample size, HSV-1 outcome measures, and diagnostic assay. Data were double extracted from relevant records by SC, MH, and HC.

Extracted outcome measures were based on their stratification in the original record. Stratifications of seroprevalence measures were considered using a pre-defined sequential order that prioritizes first population type, followed by age bracket, and then age group. Age bracket included children (<15 years of age) and adults (≥15 years of age). Age groups included <10, 10–19, 20–29, and ≥30 years of age—a stratification informed by the actual available data of age-strata.

The extracted seroprevalence data were synthesized by population type according to the following definitions:

Healthy general populations encompassing groups of presumably healthy persons (for example, pregnant women or blood donors) and outpatients attending a healthcare facility for an inconsequential health condition.

Clinical populations encompassing any population with a serious clinical condition, or with a condition potentially related to a clinical manifestation of HSV-1 infection.

Other populations encompassing populations not fitting the above definitions, or populations with an unclear risk of having acquired HSV-1, such as sex workers and mixed health-status populations.

Meta-analyses

Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted to estimate the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence in MENA by population type, age bracket, and age group. Pooled means were calculated using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects models31 whenever ≥3 measures were available. The variance of the seroprevalence measures was stabilized using the Freeman-Tukey type arcsine square-root transformation32.

Cochran’s Q statistic was calculated to test for heterogeneity in the pooled seroprevalence measures33,34. I2 measure was calculated to assess the magnitude of between-study variation that is due to true variation in seroprevalence across studies rather than chance33. Prediction interval was estimated to characterize the heterogeneity in the seroprevalence measures33.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using generalized linear mixed models (GLMM)35. The results were used to confirm the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence estimates generated based on the Freeman-Tukey type arcsine square-root transformation, given a recently-identified potential pathology in this transformation35.

Meta-analyses were performed in R version 3.4.136 using the meta package37.

Meta-regressions

Univariable and multivariable random-effects meta-regression analyses, using log-transformed proportions, were conducted to identify associations and predictors of higher HSV-1 seroprevalence and sources of between-study heterogeneity. Associations were described using relative risks (RRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values.

Potential predictors were specified a priori and included: age bracket, age group, assay type, country’s income, population type, sample size (<100 versus ≥100), sampling method (probability-based sampling versus non-probability-based sampling), year of data collection, and year of publication. Factors with p-value < 0.1 in univariable analysis were eligible for inclusion in the multivariable model. Factors with p-value < 0.05 in the multivariable analysis were considered as statistically significant predictors.

Assay type consisted of five assay types for which data were available: ELISA, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), immunofluorescence assay (IFA), neutralizing antibody assay (Nab), and western blot. Of note, different assays used different cut-off points. For example, for HerpeSelect® 1 ELISA, sera with optical density index values ≥ 1.10 were considered seropositive and <0.90 seronegative, with the rest deemed equivocal38,39. Meanwhile, for Euroimmun Anti-HSV-1 ELISA, sera with optical density index values ≥ 1.10 were considered seropositive and <0.80 seronegative, with the rest deemed equivocal39,40.

Country’s income was determined based on the World Bank classification41 for the countries for which HSV-1 seroprevalence data were available: lower-middle-income countries (Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen), upper-middle-income countries (Algeria, Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon), high-income countries (Qatar and Saudi Arabia), and mixed for samples including specimens from different countries.

Missing values in the year of data collection variable were imputed using the median of the values generated (for studies with data) for the difference between the year of data collection and the year of publication.

Meta-regressions were conducted in Stata/SE version 1342 using the package metareg43.

Quality assessment

There are documented issues with the sensitivity and specificity of HSV-1 diagnostic methods44,45. Therefore, an expert advisor, Professor Rhoda Ashley Morrow from the University of Washington, was consulted and assessed the quality of each diagnostic method in each identified relevant study. Only studies with sufficiently reliable and valid assays were included. Further quality assessment of included studies was conducted as informed by the Cochrane approach for risk of bias (ROB)29 and precision assessment.

Studies’ assessment into low versus high ROB was based on two quality domains: sampling methodology (probability-based versus non-probability-based sampling), and response rate (≥80% versus <80%). For instance, if probability-based sampling was used in a given study, the study was classified with a low ROB for that domain. Studies with missing information for any of the domains were classified as having unclear ROB for that specific domain.

Studies were considered as having high (versus low) precision if the number of HSV-1 tested individuals was at least 100 participants. For an HSV-1 seroprevalence of 80% and a sample size of 100, the 95% CI is 70.8–87.3%—a reasonable 95% CI estimate for an HSV-1 seroprevalence measure.

Results

Search results and scope of evidence

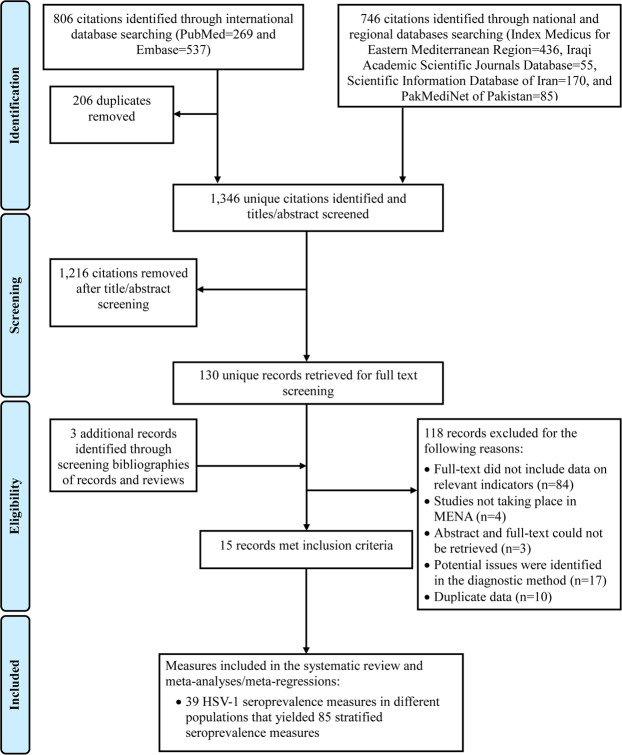

Figure 1 shows the process of study selection based on the PRISMA guidelines30. A total of 1,552 citations were retrieved (269 through PubMed, 537 through Embase, and 746 through national and regional databases). After duplicates’ removal and titles’ and abstracts’ screening, 130 records were identified as relevant or potentially relevant. Three additional records were identified through screening the bibliography of a previously published review for Iran46.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of article selection for the systematic review of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) in the Middle East and North Africa, as adapted from the PRISMA 2009 guidelines30. Abbreviations: HSV-1 = Herpes simplex virus type 1, MENA = Middle East and North Africa.

After full text screening, 15 records reporting an HSV-1 seroprevalence in 14 out of the 23 MENA countries were deemed relevant. Thirty-nine HSV-1 seroprevalence measures were extracted yielding 85 stratified measures. No HSV-1 seroprevalence measures (fulfilling the inclusion criteria) were identified among clinical children populations.

Although we searched for records that reported the proportion of GUD or genital herpes attributable to HSV-1, no such records were identified.

HSV-1 seroprevalence overview

Table 1 summarizes the included HSV-1 seroprevalence measures. Studies included were published starting the year 1986, with the majority being cross-sectional in design and based on convenience sampling methods.

Table 1.

Studies reporting herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) seroprevalence in the Middle East and North Africa.

| Author, year | Year(s) of data collection | Country | Study site | Study design | Sampling method | Population | HSV-1 serological assay | Sample size | HSV-1 seroprevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy children populations (n = 21) | |||||||||

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 1–4 years old children | ELISA | 159b | 55.2 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 5–9 years old children | ELISA | 159b | 80.5 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 10–14 years old children | ELISA | 160b | 86.4 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 1–5 years old males | ELISA | 55 | 60.0 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 6–10 years old males | ELISA | 59 | 74.5 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 1–5 years old females | ELISA | 46 | 50.0 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 6–10 years old females | ELISA | 58 | 81.1 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 6 months-2 years old infants | Nab | 34 | 23.5 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 3–5 years old children | Nab | 33 | 39.4 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 6–10 years old children | Nab | 36 | 69.4 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 11–15 years old children | Nab | 32 | 81.3 |

| Healthy adult populations (n = 60) | |||||||||

| Ahmed, 199556 | — | Pakistan | Outpatient clinic | CSa | Conv | Healthy controls | EIA | 56 | 73.2 |

| Hossain, 198657 | — | KSA | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | IFA | 1,186 | 92.0 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 21–30 years old males | ELISA | 48 | 85.4 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | >30 years old males | ELISA | 86 | 94.1 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 21–30 years old females | ELISA | 68 | 88.2 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | >30 years old females | ELISA | 43 | 95.3 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | ELISA | 55 | 100 |

| Jafarzadeh, 201158 | 2007–08 | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | >40 years old blood donors | ELISA | 60 | 33.3 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 16–20 years old adults | Nab | 32 | 87.5 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 21–30 years old adults | Nab | 32 | 96.9 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | 31–40 years old adults | Nab | 30 | 100 |

| Meguenni, 198955 | — | Algeria | Community | CS | Conv | >40 years old adults | Nab | 35 | 100 |

| Memish, 201559 | 2012–13 | KSA | Outpatient clinic | CS | RS | Healthy females | ELISA | 2,157 | 90.9 |

| Memish, 201559 | 2012–13 | KSA | Outpatient clinic | CS | RS | Healthy males | ELISA | 2,828 | 87.1 |

| Nabipour, 200660 | 2004-04 | Iran | Community | CS | Cluster RS | Healthy males | ELISA | 881 | 83.8 |

| Nabipour, 200660 | 2003–04 | Iran | Community | CS | Cluster RS | Healthy female | ELISA | 910 | 88.6 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Mixed | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Female blood donors | ELISA | 88 | 84.1 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Pakistan | Outpatient clinic | CS | RS | Blood donor Pakistani males | ELISA | 200 | 77.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Iran | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Iranian males | ELISA | 113 | 81.4 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Sudan | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Sudanese males | ELISA | 129 | 90.7 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Yemen | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Yemeni males | ELISA | 148 | 92.6 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | ≤24 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 50 | 92.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 25–29 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 50 | 100 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 30–34 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 50 | 98.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 35–39 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 50 | 98.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 40–44 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 50 | 98.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 45–49 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 50 | 100 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 50–54 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 39 | 94.9 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | ≥55 years old blood donor Egyptians males | ELISA | 19 | 100 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | ≤24 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 70.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 25–29 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 62.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 30–34 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 80.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 35–39 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 82.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 40–44 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 84.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 45–49 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 96.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 50–54 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 92.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Qatar | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | ≥55 years old blood donor Qatari males | ELISA | 50 | 92.0 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Jordan | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Jordanian males | ELISA | 200 | 86.5 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Palestine | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Palestinians males | ELISA | 200 | 80.5 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Syrian males | ELISA | 200 | 88.5 |

| Nasrallah, 201847 | 2013–16 | Lebanon | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Blood donor Lebanese males | ELISA | 118 | 81.4 |

| Obeid, 200761 | 2004–04 | KSA | Hospital | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | ELISA | 459 | 84.1 |

| Patnaik, 200762 | — | Morocco | Hospital | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | WB | 169 | 98.8 |

| Pourmand, 200963 | — | Iran | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | ELISA | 65 | 55.4 |

| Ziyaeyan, 200764 | — | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | 16–20 years old pregnant women | Nab | 104 | 83.6 |

| Ziyaeyan, 200764 | — | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | 21–25 years old pregnant women | Nab | 125 | 94.4 |

| Ziyaeyan, 200764 | — | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | 26–30 years old pregnant women | Nab | 113 | 90.3 |

| Ziyaeyan, 200764 | — | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | 31–35 years old pregnant women | Nab | 44 | 95.4 |

| Ziyaeyan, 200764 | — | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | 36–40 years old pregnant women | Nab | 14 | 100 |

| Healthy age-mixed populations (n = 5) | |||||||||

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 11–20 years old males | ELISA | 57 | 77.1 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 11–20 years old females | ELISA | 134 | 83.6 |

| RezaeiC, 201265 | 2010–11 | Iran | Outpatient clinic | CS | Cluster RS | Healthy population | ELISA | 800 | 58.4 |

| RezaeiC, 201266 | 2010–11 | Iran | Outpatient clinic | CS | Cluster RS | <85 years old patients | ELISA | 200 | 65.5 |

| Clinical adult populations (n = 20) | |||||||||

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with labials herpes | ELISA | 36 | 100 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with atherosclerosis | ELISA | 60 | 100 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Kidney transplant patients | ELISA | 32 | 96.9 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with herpetic keratitis | ELISA | 14 | 85.7 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with STDs | ELISA | 21 | 90.5 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with cervical cancer | ELISA | 51 | 100 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | HIV positive patients | ELISA | 25 | 96.0 |

| Jafarzadeh, 201158 | 2007–08 | Iran | Hospital | CS | Conv | Patients with myocardial infarction | ELISA | 120 | 60.8 |

| Janier, 199967 | 1994–94 | Mixed | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with STDs | EIA | 99 | 98.9 |

| Clinical age-mixed population (n = 4) | |||||||||

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with encephalitis | ELISA | 51 | 58.8 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | Patients with meningitis | ELISA | 21 | 85.7 |

| Other populations (n = 10) | |||||||||

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 15–19 years old healthy and HIV infected adults | ELISA | 494b | 92.2 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 20–29 years old healthy and HIV infected adults | ELISA | 494b | 92.1 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 30–34 years old healthy and HIV infected adults | ELISA | 494b | 95.0 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 35–39 years old healthy and HIV infected adults | ELISA | 494b | 98.8 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | 40–45 years old healthy and HIV infected adults | ELISA | 494b | 100 |

| Cowan, 200353 | 1998–00 | Morocco | Outpatient clinic | CS | Conv | >45 years old healthy and HIV infected adults | ELISA | 493b | 100 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–98 | Syria | Community | CS | Conv | Female sex workers | ELISA | 54 | 100 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–99 | Syria | Community | CS | Conv | Female sex workers | ELISA | 47 | 100 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–100 | Syria | Community | CS | Conv | Arab bar-girls | ELISA | 50 | 98.0 |

| Ibrahim, 200054 | 1995–101 | Syria | Community | CS | Conv | Foreign bar-girls | ELISA | 75 | 92.0 |

aActual study design was cohort but the extracted seroprevalence measure was for the baseline measurement.

bStudy included overall sample size, but no individual strata sample sizes. Each stratum sample size was assumed equal to overall sample size divided by the number of strata in the study.

Abbreviations: Conv = Convenience, CS = Cross-sectional, EIA = Enzyme immunoassay, ELISA = Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus, HSV-1 = Herpes simplex virus type 1, IFA = Indirect fluorescent assay, KSA = Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Nab = Neutralization test with neutralizing antibody, RS = Random sampling, STD = Sexually transmitted disease, TORCH = Toxoplasmosis, other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes infections, WB = Western blot.

Stratified HSV-1 seroprevalence measures (number of studies (n) = 85) varied across studies and ranged between 23.5–100% with a median of 90.3% (Table 2). The 11 seroprevalence measures in healthy children populations ranged between 23.5–86.4% with a median of 69.4%. The 49 seroprevalence measures in healthy adult populations ranged between 33.3–100% with a median of 90.7%. The 9 seroprevalence measures in clinical adult populations ranged between 60.8–100% with a median of 96.9%.

Table 2.

Pooled mean estimates for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) seroprevalence in different populations in the Middle East and North Africa.

| Population type | Studies | Samples | HSV-1 seroprevalence | Pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence | Heterogeneity measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Total n | Range | Median | Mean (95% CI) | Qa (p-value) | I²b (%) (95% CI) | Prediction Intervalc (%) | |

| Healthy general populations | ||||||||

| Children | 11 | 831 | 23.5–86.4 | 69.4 | 65.2 (53.6–76.1) | 109.2 (p < 0.0001) | 90.8 (85.6–94.2) | 22.3–97.1 |

| Adults | 49 | 11,754 | 33.3–100 | 90.7 | 89.4 (87.3–91.4) | 429.6 (p < 0.0001) | 88.8 (86.1–91.0) | 74.3–98.6 |

| Age-mixed | 4 | 1,191 | 58.4–83.6 | 71.3 | 71.1 (58.5–82.3) | 42.1 (p < 0.0001) | 92.9 (85.0–96.6) | 13.7–100 |

| All healthy general populations | 64 | 13,776 | 23.5–100 | 86.5 | 85.3 (82.3–87.9) | 1,107.9 (p < 0.0001) | 94.3 (93.2–95.1) | 59.4–99.4 |

| Clinical populations | ||||||||

| Children | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Adults | 9 | 458 | 60.8–100 | 96.9 | 95.3 (83.9–100) | 114.4 (p < 0.0001) | 93.0 (88.9–95.6) | 38.1–100 |

| Age-mixed | 2 | 72 | 58.8–85.7 | 72.2 | 66.7 (54.6–77.3) | — | — | — |

| All clinical populations | 11 | 530 | 58.8–100 | 96.0 | 92.3 (80.3–99.4) | 147.1 (p < 0.0001) | 93.2 (89.7–95.5) | 33.7–100 |

| Other populations | ||||||||

| Female sex workers | 4 | 226 | 92.0–100 | 99.0 | 95.2 (75.4–100) | 57.8 (p < 0.0001) | 94.8 (89.7–97.4) | 0.0–100 |

| Healthy/clinical adult populations | 6 | 2,963 | 92.1–100 | 96.9 | 97.5 (93.5–99.7) | 151.4 (p < 0.0001) | 96.7 (94.7–97.9) | 74.8–100 |

| Age group | ||||||||

| <10 years | 9 | 639 | 23.5–81.1 | 60.0 | 60.5 (48.1–72.3) | 73.6 (p < 0.0001) | 89.1 (81.6–93.6) | 18.4–95.0 |

| 10–19 years | 7 | 1,013 | 77.1–92.2 | 83.6 | 85.6 (80.5–90.1) | 20.5 (p = 0.0023) | 70.7 (36.0–86.6) | 68.5–96.9 |

| 20–29 years | 8 | 980 | 62.0–100 | 91.2 | 90.7 (84.7–95.5) | 43.8 (p < 0.0001) | 84.0 (70.2–91.4) | 66.2–100 |

| ≥30 years | 24 | 2,965 | 33.3–100 | 95.7 | 94.3 (89.5–97.9) | 433.2 (p < 0.001) | 94.7 (93.2–95.9) | 60.9–100 |

| All children | 11 | 831 | 23.5–86.4 | 69.4 | 65.2 (53.6–76.1) | 109.2 (p < 0.0001) | 90.8 (85.6–94.2) | 22.3–97.1 |

| All adults | 68 | 15,401 | 33.3–100 | 92.0 | 91.8 (89.6–93.7) | 1,087 (p < 0.0001) | 93.8 (92.8–94.7) | 71.0–100 |

| All age-mixed | 6 | 1,263 | 58.4–85.7 | 71.3 | 71.1 (60.7–80.6) | 47.5 (p < 0.0001) | 89.5 (79.7–94.5) | 34.2–96.8 |

| All studies | 85 | 17,495 | 23.5–100 | 90.3 | 88.0 (85.3–90.5) | 1,973.8 (p < 0.0001) | 95.7 (95.2–96.2) | 58.4–100 |

aQ: The Cochran’s Q statistic is a measure used here to assess the existence of heterogeneity in seroprevalence measures across studies.

bI2: A measure used here to assess the magnitude of between-study variation that is due to actual differences in seroprevalence across studies rather than chance.

cPrediction interval: A measure used here to estimate the distribution (the 95% interval) of true seroprevalence around the estimated pooled mean.

Abbreviations: CI = Confidence interval, HSV-1 = Herpes simplex virus type 1.

Pooled mean seroprevalence estimates

Table 2 summarizes the results of the meta-analyses. In healthy general populations, the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence was 65.2% (95% CI: 53.6–76.1%) for children, and 89.4% (95% CI: 87.3–91.4%) for adults. In adult clinical populations, the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence was 95.3% (95% CI: 83.9–100%). Among other populations, the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence was 95.2% (95% CI: 75.4–100%) in female sex workers, and 97.5% (95% CI: 93.5–99.7%) in mixed health-status populations.

By age group, the pooled mean HSV-1 seroprevalence was lowest at 60.5% (95% CI: 48.1–72.3%) in those aged <10 years, followed by 85.6% (95% CI: 80.5–90.1%) in those aged 10–19 years, 90.7% (95% CI: 84.7–95.5%) in those aged 20–29 years, and 94.3% (95% CI: 89.5–97.9%) in those aged ≥30 years. The sensitivity analyses using GLMM methods produced similar results (Supplementary Table S2).

Evidence of heterogeneity in seroprevalence was present in nearly all meta-analyses (p < 0.0001; Table 2). The I² measure indicated that most variation was attributed to true variability in seroprevalence across studies. The prediction intervals confirmed the considerable variation in seroprevalence across studies.

Forest plots of meta-analyses can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Predictors of seroprevalence and sources of between-study heterogeneity

Table 3 summarizes the results of the univariable and multivariable meta-regression models. In the univariable analyses, age bracket, age group, country’s income, population type, and sampling method had a p-value < 0.1 and were included in the multivariable analyses. Age bracket alone explained 44.3% of the variation in seroprevalence, followed by age group at 28.7%. Each of assay type, sample size, sex, year of data collection, and year of publication was not significantly associated with HSV-1 seroprevalence.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable meta-regression analyses for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) seroprevalence in the Middle East and North Africa.

| Studies | Samples | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Total n | RR (95% CI) | p-value | Variance explained adjusted R2 (%) | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

| ARR (95% CI) | p-value | ARR (95% CI) | p-value | |||||||

| Age bracket | Children | 11 | 831 | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | — | — | |

| Adults | 68 | 15,401 | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 0.000 | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 0.000 | — | — | ||

| Age-mixed | 6 | 1,263 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.806 | 44.3 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.580 | — | — | |

| Age group | <10 | 9 | 639 | 1.0 | — | — | — | 1.0 | — | |

| 10–19 | 7 | 1,013 | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.003 | — | — | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.002 | ||

| 20–29 | 8 | 980 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.000 | — | — | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 0.000 | ||

| ≥30 | 24 | 2,965 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.000 | — | — | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 0.000 | ||

| Mixed | 37 | 11,898 | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 0.000 | 28.7 | — | — | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.000 | |

| Assay type | ELISA | 68 | 15,321 | 1.0 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| EIA | 2 | 155 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.915 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Nab | 13 | 664 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.826 | — | — | — | — | ||

| IFA | 1 | 1,186 | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.687 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Western blot | 1 | 169 | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 0.434 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Country’s income | LMIC | 49 | 6,347 | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | |

| UMIC | 22 | 3,931 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.016 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.044 | 0.8 (0.8–1.0) | 0.044 | ||

| HIC | 12 | 7,030 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.440 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.076 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.101 | ||

| Mixed | 2 | 187 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.822 | 3.3 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.847 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.848 | |

| Population type | Healthy general populations | 64 | 13,776 | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | |

| Clinical populations | 11 | 530 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.355 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.967 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.987 | ||

| Other populations | 10 | 3,189 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.064 | 4.6 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.839 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.706 | |

| Sample sizec | <100 | 14 | 679 | 1.0 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| ≥100 | 71 | 16,816 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.712 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Sampling method | Non-probability-based | 81 | 14,704 | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | |

| Probability based | 4 | 2,791 | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.070 | 9.3 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.621 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.251 | |

| Sex | Female | 23 | 6,115 | 1.0 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Male | 31 | 6,080 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.713 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Mixed | 31 | 5,300 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.210 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Year of data collection | 85 | 17,495 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.993 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Year of publication | 85 | 17,495 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.911 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | — |

aVariance explained by the final multivariable model 1 (adjusted R2) = 48.6%.

bVariance explained by the final multivariable model 2 (adjusted R2) = 40.2%.

cSample size denotes the sample size of the study population found in the original publication.

Abbreviations: ARR = Adjusted relative risk, CI = Confidence interval, EIA = Enzyme immunoassay, ELISA = Enzyme-linked immunosorbent type-specific assay, HIC = High-income country, IFA = Immunofluorescence assay, LMIC = Lower-middle-income country, Nab = Neutralizing antibody assay, RR = Relative risk, UMIC = Upper-middle-income country.

To account for the fact that age bracket and age group both measure age, two final multivariable models were conducted. The first model included age bracket, country’s income, population type, and sampling method. This model explained 48.6% of seroprevalence variation. HSV-1 seroprevalence in adults was 1.3-fold (95% CI: 1.2–1.5) higher than in children. Seroprevalence in upper-middle-income countries and high-income countries was, in both, 0.9-fold (95% CI: 0.8–1.0) lower than in lower-middle-income countries. No association with population type and sampling method was found.

The second model included age group, assay type, country’s income, population type, and sampling method. The model explained 40.2% of seroprevalence variation, with similar results for country’s income, population type, and sampling method as in the first model. Compared to HSV-1 seroprevalence in those <10 years old, seroprevalence was 1.3-fold (95% CI: 1.1–1.6) higher in those 10–19 years old, 1.4-fold (95% CI: 1.2–1.7) higher in those 20–29 years old, and 1.5-fold (95% CI: 1.3–1.7) higher in those ≥30 years old.

Quality assessment

Out of 32 records that included seroprevalence measures, only 15 were included in the systematic review with the remaining 17 being excluded due to potential issues in the validity of the diagnostic method, such as potential cross-reactivity with HSV-2 antibodies (Fig. 1). Of the studies included, 64.1% had high precision, 7.7% had low ROB for the sampling methodology domain, and 48.7% had low ROB for the response rate domain. These results, in context of the meta-regression models results, with different factors including sample size, sampling method, and assay type not being predictors of HSV-1 seroprevalence, suggest that overall the studies had reasonable quality.

The detailed quality assessment of included studies can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

Discussion

HSV-1 epidemiology in MENA was investigated through a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analytics of existing evidence. HSV-1 seroprevalence was found at high level, suggesting considerable HSV-1-related morbidity that is yet to be quantified and tackled. Sixty-five percent of children and 90% of adults were found seropositive—seroprevalence increased rapidly with age at younger ages, and was consistent with most infections being acquired in childhood.

Remarkably, about half of the observed variation in seroprevalence was explained by factors set a priori and examined in this study. Age alone explained 44.3% of the variation. Despite improvements in socio-economic conditions and earlier speculation that seroprevalence levels may have been declining in MENA47, we did not find evidence for a declining trend over the last two decades. We also did not find evidence for variation in seroprevalence by sex, population type (healthy versus clinical), or study characteristics including assay type, sampling method, and sample size.

Though there was no evidence for recent declines in seroprevalence, youth had considerably lower HSV-1 seroprevalence than older subjects. As much as one-third of youth in MENA may be reaching sexual debut uninfected and thus potentially at risk of sexual acquisition, in context of recent evidence from Western countries and Asia reporting an increase in incidence of genital herpes attributed to HSV-1 rather than HSV-26,21–26. We did not, nonetheless, identify any evidence for a potential role for HSV-1 sexual transmission in MENA. Despite the extensive search in multiple international, regional, and national databases, we failed to identify a single study that assessed the etiological role of HSV-1 in GUD or genital herpes in this region.

A comparison of the findings of the present study with that of a recent systematic review of HSV-1 in Asia21 demonstrates key insights about what may be general (or somewhat general) patterns in the global epidemiology of HSV-1 infection. Age in both systematic reviews was by far the strongest predictor of HSV-1 seroprevalence. Remarkably, in both MENA and Asia, seroprevalence in children was assessed at about 60%, and seroprevalence among adults was about 30% higher than that in children. Country’s income was also a predictor of seroprevalence with higher income associated with lower seroprevalence, attesting to an apparently global association between HSV-1 infection and socio-economic status11,48. However, the association of HSV-1 and socio-economic status differed between the two regions. In MENA, lower-middle-income countries had the highest seroprevalence, whereas in Asia, upper-middle-income countries had the highest seroprevalence. Possibly, the rapid modernization of Asia compared to MENA may contribute to explaining this difference.

In both MENA and Asia, sex, population type, assay type, sample size, and sampling method were not associated with HSV-1 seroprevalence. This suggests that HSV-1 is a truly general population infection that permeates all strata of society—there is no difficulty in sampling a representative sample provided the age distribution is representative. In both regions also, no evidence for a temporal trend in seroprevalence was identified despite the evidence for temporal declines in seroprevalence in Western countries11,13–20. Notably in MENA, half of the variation in seroprevalence (49%) was explained by the a priori considered factors, but only 26% of the variation was explained in Asia by the same considered factors21. The latter finding may relate to a higher population heterogeneity across countries in Asia than in MENA.

Our review and meta-analytics are limited by the quantity, quality, and representativeness of included studies. No data were identified for nine (mostly non-populous) of the 23 MENA countries, thereby potentially affecting the generalizability of the analyses to all of MENA. The number of seroprevalence measures varied from each study to another—only one (large) study, for example, contributed 29% of all stratified seroprevalence measures47. The majority of studies used convenience sampling (as opposed to probability-based sampling) of opportunistic populations such as blood donors or outpatients (Table 1). The latter, though, may not have been a limitation in context of the findings of the meta-regression analyses (Table 3).

Studies used different diagnostic methods, and such methods may differ in sensitivity and specificity44,45. Presence of HSV-2 antibodies may also affect diagnostic methods differentially, particularly the classic “relative-reactivity” methods such as IFA and Nab49–51. This limitation, however, may not have affected our results, as HSV-2 infection has a low seroprevalence in MENA52, and earlier work suggests minimal impact of this limitation on specifically HSV-1 seroprevalence (as opposed to HSV-2 seroprevalence)49–51. The meta-regression analyses found no variations in HSV-1 seroprevalence across assay types (Table 3).

There was extensive heterogeneity in HSV-1 seroprevalence measures, but half of this heterogeneity was subsequently explained by only two factors, age and country’s income (Table 3). Lastly, no study of HSV-1 viral detection in GUD or in genital herpes in MENA was identified, thus limiting our ability to assess the epidemiological role of HSV-1 sexual transmission. In spite of these limitations, our study is the first to draw a comprehensive synthesis and analytics of HSV-1 seroprevalence for the MENA region, and to highlight opportunities for related research and public health response.

Conclusions

HSV-1 seroprevalence in MENA indicated that 65% of children and 90% of adults had been exposed to this infection, by inference, most often during childhood. Age and country’s income were the strongest predictors of HSV-1 seroprevalence and explained half of seroprevalence variation. No evidence was found for a temporal trend in seroprevalence over the last two decades despite improvements in socio-economic conditions. With no identified study of HSV-1 viral detection in GUD or in genital herpes, the role of HSV-1 sexual transmission in MENA remains unknown. This lack of data calls for at least basic or opportunistic GUD/genital herpes etiological surveillance. The totality of the findings highlights the timeliness of accelerating HSV-1 vaccine development to control one of the most endemic infections worldwide.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Emeritus Rhoda Ashley Morrow from the University of Washington, for her support in assessing the quality of study diagnostic methods and for critically reviewing the manuscript. The authors are also grateful for the administrative support of Ms. Adona Canlas. This publication was made possible by NPRP grant number 9-040-3-008 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The findings achieved herein are solely the responsibility of the authors. The authors are also grateful for pilot funding provided by the Biomedical Research Program and infrastructure support provided by the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core, both at Weill Cornell Medicine in Qatar.

Author Contributions

S.C. and M.H. conducted the systematic search, screening, data extraction, and data analysis. H.C. provided support in study design and data extraction. G.S. provided methodological contributions in data analysis. L.J.A. conceived the study and supervised study conduct and analyses. S.C. and M.H. with L.J.A. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sonia Chaabane and Manale Harfouche contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-37833-8.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Herpes simplex virus (Available at, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs400/en/#hsv1, accessed in August, 2017) (2017).

- 2.Looker KJ, et al. Global and Regional Estimates of Prevalent and Incident Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infections in 2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald, A. & Corey, L. Persistence in the population: epidemiology, transmission (2007). [PubMed]

- 4.Ramchandani M, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 shedding in tears and nasal and oral mucosa of healthy adults. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43:756–760. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark KE, et al. Rapidly cleared episodes of herpes simplex virus reactivation in immunocompetent adults. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;198:1141–1149. doi: 10.1086/591913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein DI, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;56:344–351. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady RC, Bernstein DI. Treatment of herpes simplex virus infections. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fatahzadeh, M. & Schwartz, R. A. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol57, 737–763, quiz 764–736, 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.027 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gnann JW, Jr., Whitley RJ. Genital Herpes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375:666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1603178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryder N, Jin F, McNulty AM, Grulich AE, Donovan B. Increasing role of herpes simplex virus type 1 in first-episode anogenital herpes in heterosexual women and younger men who have sex with men, 1992–2006. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:416–419. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith J, Robinson N. Age-SPecific Prevalence of Infection with Herpes Simplex Virus Types 2 and 1: A Global Review. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;186:S3–S28. doi: 10.1086/343739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nahmias AJ, Lee FK, Beckman-Nahmias S. Sero-epidemiological and -sociological patterns of herpes simplex virus infection in the world. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1990;69:19–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:964–973. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer, M. A. et al. Ethnic differences in HSV1 and HSV2 seroprevalence in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Euro Surveill13 (2008). [PubMed]

- 15.Xu F, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 in children in the United States. J Pediatr. 2007;151:374–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wutzler P, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in selected German populations-relevance for the incidence of genital herpes. J Med Virol. 2000;61:201–207. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(200006)61:2<201::AID-JMV5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sauerbrei, A. et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in Thuringia, Germany, 1999 to 2006. Euro Surveill16 (2011). [PubMed]

- 18.Pebody RG, et al. The seroepidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 in Europe. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:185–191. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.005850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aarnisalo J, et al. Development of antibodies against cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in Finland during the first eight years of life: a prospective study. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:750–753. doi: 10.1080/00365540310015881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vyse AJ, et al. The burden of infection with HSV-1 and HSV-2 in England and Wales: implications for the changing epidemiology of genital herpes. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:183–187. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khadr L, et al. The epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 in Asia: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts CM, Pfister JR, Spear SJ. Increasing proportion of herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes infection in college students. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:797–800. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000092387.58746.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowhagen GB, Tunback P, Andersson K, Bergstrom T, Johannisson G. First episodes of genital herpes in a Swedish STD population: a study of epidemiology and transmission by the use of herpes simplex virus (HSV) typing and specific serology. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:179–182. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.3.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsen A, Myrmel H. Changing trends in genital herpes simplex virus infection in Bergen, Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:693–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samra Z, Scherf E, Dan M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 is the prevailing cause of genital herpes in the Tel Aviv area, Israel. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:794–796. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000079517.04451.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert M, et al. Using centralized laboratory data to monitor trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infection in British Columbia and the changing etiology of genital herpes. Can J Public Health. 2011;102:225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF03404902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottlieb, S. L. et al. Modelling efforts needed to advance herpes simplex virus (HSV) vaccine development: Key findings from the World Health Organization Consultation on HSV Vaccine Impact Modelling. Vaccine, 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.074 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Gottlieb SL, et al. The global roadmap for advancing development of vaccines against sexually transmitted infections: Update and next steps. Vaccine. 2016;34:2939–2947. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins, J. & Green, S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Vol. 4 (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. & Rothstein, H. R. Front Matter, in Introduction to Meta-Analysis. (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009).

- 32.Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Ann Math Statist. 1950;21:607–611. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177729756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borenstein, M. Introduction to meta-analysis. (John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

- 34.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwarzer, G., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Chemaitelly, H. & Rucker, G. Seriously misleading result using inverse of Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions (under review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, http://www.rstudio.com/ (2015).

- 37.Schwarzer G. Meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News. 2007;7:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Focus Diagnostics. HerpeSelect 1 ELISA IgG (English) (2011).

- 39.Aldisi RS, et al. Performance evaluation of four type-specific commercial assays for detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 antibodies in a Middle East and North Africa population. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2018;103:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Euroimmun. Anti-HSV-1 (gC1) ELISA (IgG) (2016).

- 41.World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups (Available at, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed in June 2017), 2017).

- 42.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP (2015).

- 43.Harbord RM, Higgins JPT. Meta-regression in Stata. Stata Journal. 2008;8:493–519. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0800800403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashley-Morrow R, Nollkamper J, Robinson NJ, Bishop N, Smith J. Performance of focus ELISA tests for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 antibodies among women in ten diverse geographical locations. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:530–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashley RL. Performance and use of HSV type-specific serology test kits. Herpes. 2002;9:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malary M, Abedi G, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Afshari M, Moosazadeh M. The prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infection in Iran: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine. 2016;14:615–624. doi: 10.29252/ijrm.14.10.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasrallah GK, Dargham SR, Mohammed LI, Abu‐Raddad LJ. Estimating seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 among different Middle East and North African male populations residing in Qatar. Journal of medical virology. 2018;90:184–190. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2–United States, 1999-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325–333. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashley R, Cent A, Maggs V, Nahmias A, Corey L. Inability of enzyme immunoassays to discriminate between infections with herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Annals of internal medicine. 1991;115:520–526. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ashley RL, et al. Underestimation of HSV-2 seroprevalence in a high-risk population by microneutralization assay. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1993;20:230–235. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherlock C, Ashley R, Shurtleff M, Mack K, Corey L. Type specificity of complement-fixing antibody against herpes simplex virus type 2 AG-4 early antigen in patients with asymptomatic infection. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1986;24:1093–1097. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.6.1093-1097.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. HSV-2 serology can be predictive of HIV epidemic potential and hidden sexual risk behavior in the Middle East and NorthAfrica. Epidemics. 2010;2:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cowan FM, et al. Seroepidemiological study of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Brazil, Estonia, India, Morocco, and Sri Lanka. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:286–290. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ibrahim AI, Kouwatli KM, Obeid MT. Frequency of herpes simplex virus in Syria based on type-specific serological assay. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meguenni S, et al. Herpes simplex virus infections in Algiers. Arch Inst Pasteur Alger. 1989;57:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahmed S, Jafarey NA. Association of herpes simplex virus type-I and human papilloma virus with carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Journal of environmental pathology, toxicology and oncology: official organ of the International Society for Environmental Toxicology and Cancer. 1995;14:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hossain A, Bakir TM, Ramia S. Immune status to congenital infections by TORCH agents in pregnant Saudi women. J Trop Pediatr. 1986;32:83–86. doi: 10.1093/tropej/32.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jafarzadeh A, et al. The association between infection burden in Iranian patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Acta Med Indones. 2011;43:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Memish ZA, et al. Seroprevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Type 2 and Coinfection With HIV and Syphilis: The First National Seroprevalence Survey in Saudi Arabia. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:526–532. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000336.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nabipour I, Vahdat K, Jafari SM, Pazoki R, Sanjdideh Z. The association of metabolic syndrome and Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 1: the Persian Gulf Healthy Heart Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Obeid OE. Prevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and associated sociodemographic variables in pregnant women attending king fahd hospital of the university. J Family Community Med. 2007;14:3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patnaik P, et al. Type-specific seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 and associated risk factors in middle-aged women from 6 countries: the IARC multicentric study. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:1019–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pourmand D, Janbakhash A. Seroepidemiology of herpes simplex virus type one in pregnant women referring to health care centers of Kermanshah (2004) Behboob. 2009;14:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ziyaeyan M, Japoni A, Roostaee MH, Salehi S, Soleimanjahi H. A serological survey of Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 and 2 immunity in pregnant women at labor stage in Tehran, Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10:148–151. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.148.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rezaei-Chaparpordi, S. et al. Seroepidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 in northern iran. Iran J Public Health41, 75–79. Epub 2012 Aug 2031 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Rezaei-Chaparpordi S, et al. Seroepidemiology of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and 2 in Anzali city 2010–2011. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2012;14:67–69. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Janier M, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 antibodies in an STD clinic in Paris. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10:522–526. doi: 10.1177/095646249901000805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.