Abstract

Testis‐expressed X‐linked genes typically evolve rapidly. Here, we report on a testis‐expressed X‐linked microRNA (miRNA) cluster that despite rapid alterations in sequence has retained its position in the Fragile‐X region of the X chromosome in placental mammals. Surprisingly, the miRNAs encoded by this cluster (Fx‐mir) have a predilection for targeting the immediately adjacent gene, Fmr1, an unexpected finding given that miRNAs usually act in trans, not in cis. Robust repression of Fmr1 is conferred by combinations of Fx‐mir miRNAs induced in Sertoli cells (SCs) during postnatal development when they terminate proliferation. Physiological significance is suggested by the finding that FMRP, the protein product of Fmr1, is downregulated when Fx‐mir miRNAs are induced, and that FMRP loss causes SC hyperproliferation and spermatogenic defects. Fx‐mir miRNAs not only regulate the expression of FMRP, but also regulate the expression of eIF4E and CYFIP1, which together with FMRP form a translational regulatory complex. Our results support a model in which Fx‐mir family members act cooperatively to regulate the translation of batteries of mRNAs in a developmentally regulated manner in SCs.

Keywords: evolution, FMR1, microRNA, testis, translation

Subject Categories: Development & Differentiation, Molecular Biology of Disease, RNA Biology

Introduction

Conventional wisdom holds that conserved genes are critical for biological processes. However, an emerging area of interest is rapidly diverging genes, as these have the potential to confer species‐specific traits while simultaneously retaining ancient functions 1, 2. Testes‐expressed genes are a particularly rich source of genes undergoing rapid evolution 3, 4. While the underlying mechanism is not known, evidence suggests that strong selection pressures—including post‐copulatory sexual selection mechanisms (e.g., sperm competition)—drive the rapid sequence alterations in testes‐expressed genes 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Particularly enriched for rapidly evolving genes is the mammalian X chromosome, in part, because it is single copy in males and thus can allow for rapid fixation of sequence alterations that confer a selective advantage in spermatogenesis and other male‐associated functions 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

In this communication, we investigate the evolution, expression, and function of an X‐linked microRNA (miRNA) cluster. miRNAs are small (~22 nt) RNAs that regulate gene expression through translational repression or destabilization of their target transcripts 15, 16, 17. Mammalian genomes encode hundreds of miRNAs, many of which are spatially and temporally regulated 18. In turn, each miRNA can potentially target hundreds of mRNAs 19. miRNAs have important functions in many aspects of cellular differentiation and homeostasis, and consequently have roles in many pathologies, including cancer, neural disease, and infertility 20, 21, 22. About 40% of microRNAs are estimated to form clusters whose physiological importance is largely unknown 23. In contrast, the roles of individual miRNAs have been defined in a variety of physiological and pathological states 24, 25.

In this report, we report the discovery of a miRNA cluster in the Fragile‐X region of the X chromosome with unusual functional qualities that has undergone rapid evolution in placental mammals. The miRNAs encoded by this cluster are primarily expressed in the testis, thereby providing an explanation for their rapid evolution. Given that miRNAs act in trans, not in cis, we were surprised to find that a large number of the miRNAs in this Fragile‐X cluster target the immediately adjacent gene: FMR1. Indeed, the position of this miRNA cluster next to FMR1 is evolutionarily conserved in placental mammals. Given that FMR1 encodes a translational regulator 26, we examined the role of members of this Fragile‐X miRNA cluster in regulating translation, as well as the biological contexts in which it acts. Our findings have implications for evolution, spermatogenesis, and the diagnosis and treatment of male infertility.

Results

Fx‐mir—a rapidly evolving miRNA cluster directly adjacent to Fmr1

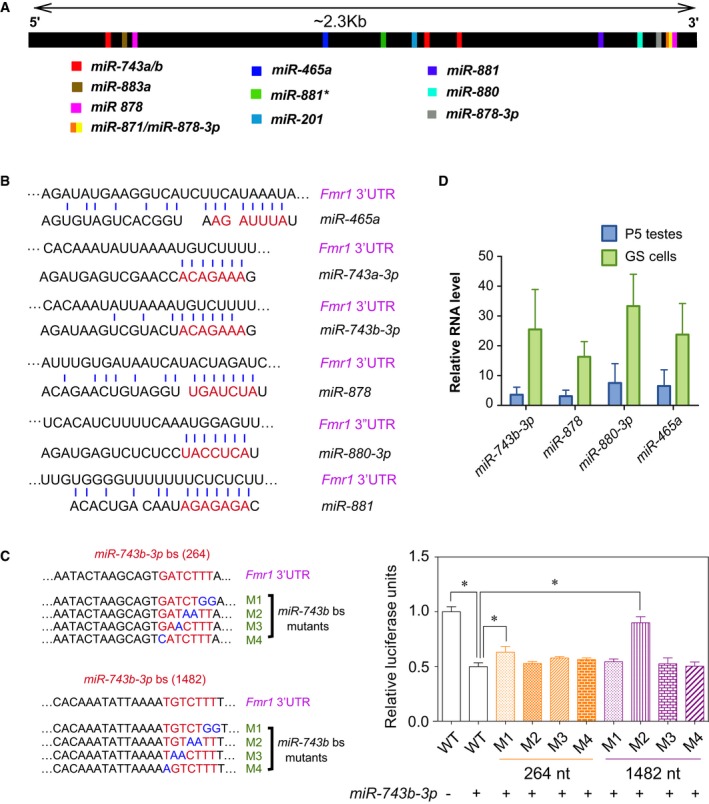

Our long‐term interest in miRNAs, X‐linked gene clusters, and intellectual disability 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 led us to note the existence of a large group of miRNAs in the Fragile‐X region of the mouse X chromosome (Fig 1A). The Fragile‐X region is best known for housing the FMR1 gene, which when mutated, causes Fragile‐X Syndrome (FXS), the most common form of inherited intellectual disability in humans 32, 33, 34. The Fragile‐X region also harbors several other protein‐coding genes that have been given the “Fragile X” designation (Appendix Fig S1A). Thus, we elected to name the miRNA cluster in this region the “Fragile‐X miRNA (Fx‐mir)” cluster. There are no annotated protein‐coding genes interrupting the miRNA genes in the mouse Fx‐mir cluster. All 22 miRNAs in this cluster are oriented in the same direction, raising the possibility that these miRNAs could all be derived from a single transcription unit.

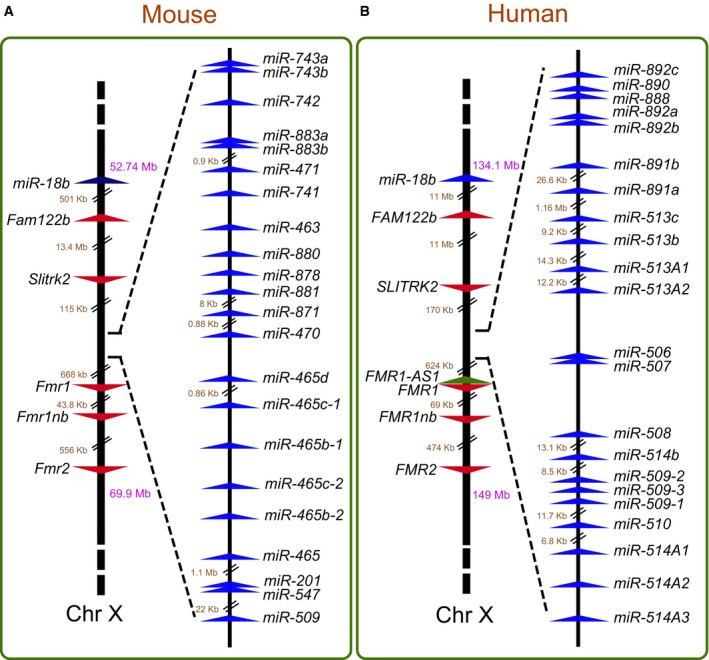

Figure 1. The mouse and human Fx‐mir (FX‐MIR) cluster.

-

A, BFor each panel, left shows the location of Fx‐mir cluster (A) or FX‐MIR cluster (B) on the X chromosome relative to neighboring genes. The numbers in purple represent the chromosomal position of the genes while the numbers in brown indicate intergenic distances. Right shows the relative position of Fx‐mir/FX‐MIR family members, drawn to scale, except when indicated. The arrowheads indicate the transcriptional direction of the genes.

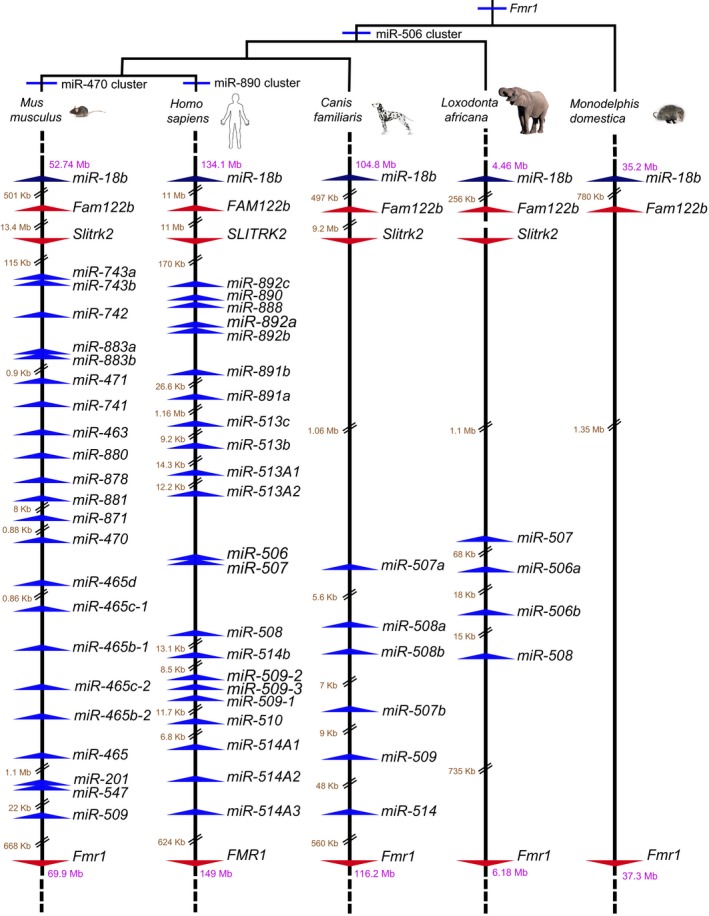

To gain insight into the evolutionary origins of this cluster, we mapped the Fx‐mir cluster in multiple species, based on available Ensembl assemblies. We examined three placental mammals [human (Homo sapien), dog (Canis familiaris), and elephant (Loxodonta africana)] in addition to mice and observed that all four of these mammalian species have a miRNA cluster between the Fmr1 and Slitrk2 protein‐coding genes (Fig EV1). In contrast, no observable miRNA cluster is present in the non‐placental mammal opossum (Monodelphis domestica) (Fig EV1). Although the Slitrk2 gene appears to be specific to placental mammals, a broader syntenic analysis shows that the linear relationship between Fmr1 and two upstream markers, Fam122b and the miR‐18b miRNA cluster, is retained in all five species we examined, including opossum, thereby allowing us to unambiguously conclude that opossum lacks the Fx‐mir cluster, at least at its chromosomal location in placental mammals. Together, our results indicate that the Fx‐mir cluster is present at a conserved location in the Fragile‐X region of placental mammals.

Figure EV1. Evolution of the Fx‐mir cluster.

The location of Fx‐mir miRNAs relative to each other and nearby protein‐coding genes. Drawn to scale unless indicated. miRNAs deposited in miRBase are indicated for mouse, human, and all but miR‐509 for dog. For dog miR‐509 and all elephant Fx‐mir family members, we assigned names to the genes indicated in the Ensembl database based on phylogenetic similarity to the mouse and human entries. Note that the paucity of Fx‐mir family members for both dog and elephant is likely artifactual due to poorer miRNA characterization in these two taxa relative to mouse and human.

Because the human and mouse genomes are well annotated, we focused our subsequent analysis on the Fx‐mir cluster in these two species. Both the mouse Fx‐mir and human FX‐MIR clusters consist of the same number of miRNAs (Figs 1A and B). Furthermore, all the miRNA genes are oriented in the same transcriptional direction in both the mouse and human clusters. In striking contrast to these conserved features, only one miRNA encoded by these clusters has retained sufficient sequence similarity in mice and humans to be clearly defined as an ortholog (Fig 1). This miRNA, miR‐509, displayed considerable sequence identity between both mouse and humans throughout the length of its precursor (Appendix Fig S1B). Furthermore, most of the seed sequence in mature miR‐509 is identical between mice and humans. To screen for other candidate orthologous miRNAs within this cluster, we aligned each of the 22 mouse Fx‐mir miRNA precursor sequence with each of the 22 human FX‐MIR precursor sequences (data not shown). This analysis revealed considerable sequence identity between the precursor sequences of mouse miR‐881 and human miR‐892a, as well as between mouse miR‐880 and both human miR‐888 and miR‐890 (Appendix Fig S1C). However, there is only limited sequence identity in the seed region, precluding defining these miRNAs as being definitive orthologs.

Mouse Fx‐mir cluster family members target Fmr1

Using several miRNA target prediction programs, we noted that a frequent putative direct target of several members of the mouse Fx‐mir cluster is Fmr1, the directly adjacent gene (Fig 1A). To systematically test the possibility that Fx‐mir family members have a predilection for targeting Fmr1, we first performed an in silico screen to identify all miRNAs predicted to regulate Fmr1. We used two target prediction programs—TargetScan and microRNA.org—to increase the probability of identifying bona fide targets. Both conserved and non‐conserved miRNAs were considered using the miRanda target sites and mirSVR scores provided by microRNA.org 35. Appendix Table S1 lists the 15 miRNAs with the highest prediction scores of the 1,915 candidate mouse miRNAs in miRBase that were analyzed. Two of the top 15 miRNAs predicted to target Fmr1 are encoded by Fx‐mir cluster. One of these two miRNAs, miR‐743b‐3p, has the second highest prediction score (Appendix Table S1). We next extended our in silico analysis to screen all miRNAs predicted to target Fmr1 and found that 15 miRNAs in the Fx‐mir cluster are predicted to target Fmr1. Table EV1 provides a list of “high‐confidence” miRNAs that had a mirSVR score of < −0.5 (indicated in blue); a number of these were also predicted by the TargetScan algorithm (Table EV1). Some of these high‐confidence miRNAs target more than one site, bringing the total number of predicted Fx‐mir‐binding sites in the Fmr1 3′UTR to 21.

To address whether the Fx‐mir cluster has more of a propensity to target Fmr1 than other testes‐expressed genes, we compared the number of predicted Fx‐mir‐binding sites in the 3′UTR of Fmr1 to the 3′UTR from other genes expressed in testes (Table EV2). This analysis revealed that the Fmr1 3′UTR had more predicted target sites than did the 3′UTRs of other randomly chosen genes (Table EV2), four of which (Ar, Vegf, Dazl, and Foxi1) we empirically showed through reporter analysis are targeted by at least one Fx‐mir family member. To more systematically address this question, we took advantage of a recent study identifying genes exhibiting enriched expression in Sertoli cells (SCs) 36, the primary testicular cell type that expresses several Fx‐mir family members (see below). These ~500 SC‐enriched genes were identified by RiboTag analysis of testes specifically expressing a tagged ribosomal subunit in SCs 36. We asked which of these ~500 SC‐enriched genes are targeted by Fx‐mir family members by mining target site predictions (microRNA.org), using a mirSVR score of < −0.5. This analysis revealed that Fmr1 had more predicted Fx‐mir target sites than any of the other SC‐enriched genes (Fig 2A [red line] and Appendix Table S2), and supports the hypothesis that the Fx‐mir cluster has a strong predilection for targeting the neighboring gene, Fmr1.

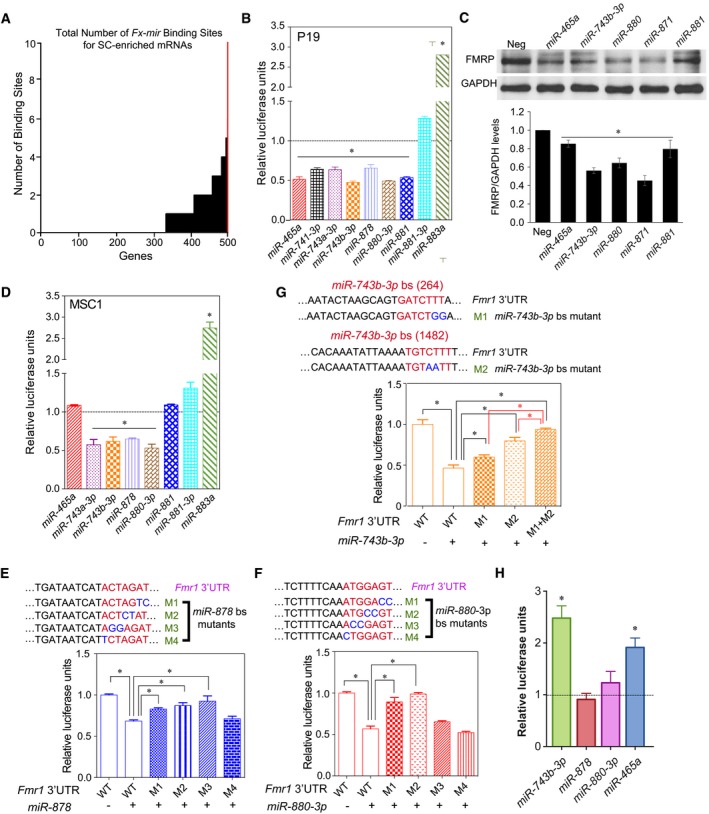

Figure 2. Mouse Fx‐mir family members directly regulate Fmr1 .

-

ANumber of Fx‐mir predicted binding sites in mouse SC‐enriched genes. The Y‐axis shows the number of binding sites predicted from microRNA.org target site predictions, and the X‐axis shows the number of genes targeted with 0–10 sites. The red line is Fmr1.

-

B–DLuciferase analysis of P19 cells (panel B) and MSC1 cells (panel D) co‐transfected with the pMIR‐luciferase reporter harboring the mouse Fmr1 3′UTR and the indicated Fx‐mir miRNA precursors. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency. The luciferase activity of cells transfected with a negative‐control scrambled precursor is set to 1. (C) Western blot analysis of endogenous FMRP protein levels in P19 cells transfected with respective Fx‐mir miRNAs or a negative‐control miRNA precursor. The bottom panel shows mean FMRP levels relative to the internal control (GAPDH).

-

E–GLuciferase analysis of MSC1 cells co‐transfected with (i) a miRNA precursor or a negative‐control scrambled miRNA precursor and (ii) the pMIR‐luciferase reporter with the wild‐type version of the mouse Fmr1 3′UTR or mutant versions with the indicated predicted miRNA‐binding site (bs) mutations. The seed sequences are depicted in red and the mutations are in blue. miR‐878 (panel E) and miR‐880 (panel F) have one major predicted binding sites, while miR‐743b‐3p (panel G) has three predicted binding sites, two of which were mutated, as described in the text. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

-

HLuciferase analysis of GS cells co‐transfected with the pMIR‐luciferase reporter harboring the mouse Fmr1 3′UTR and the indicated Fx‐mir miRNA competitors. The luciferase activity of cells transfected with a negative‐control scrambled competitor is set to 1.

To empirically test whether Fx‐mir family members target Fmr1, we first employed reporter analysis. The full‐length 3′UTR of Fmr1 was cloned into a firefly luciferase reporter vector, and this reporter was co‐transfected into the P19 mouse teratocarcinoma cell line 37 with selected Fx‐mir miRNA precursors. This analysis identified 6 Fx‐mir family members that downregulated Fmr1 3′UTR‐driven reporter expression (Fig 2B; of note, miRNAs without a 5p/3p designation are from the 5p strand). The reduction in reporter expression was consistent with the known action of most miRNAs, which suppress their targets 38, 39. Downregulation of FMRP by Fx‐mir family members was also confirmed at the protein level by Western blot analysis (Figs 2C and EV2A).

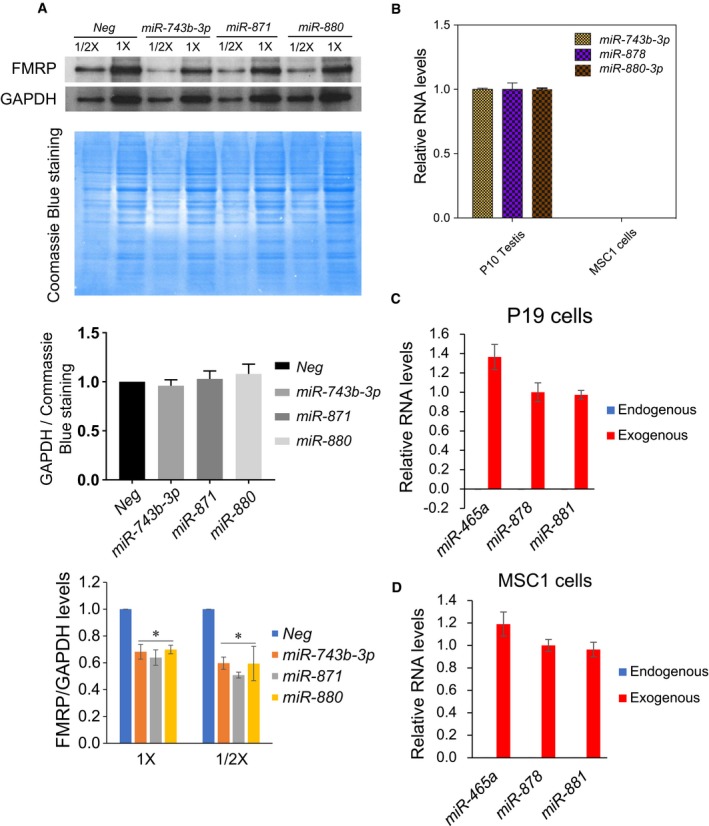

Figure EV2. Fx‐mir family members directly regulate Fmr1 .

-

AFx‐mir miRNAs repress FMRP protein expression. Top: Western blot analysis of endogenous FMRP protein levels in P19 cells transfected with the indicated Fx‐mir miRNA precursors or a negative‐control miRNA precursor (Neg). The loading sample amounts are 15 μg (1 X) and 7.5 μg (1/2 X) total protein, based on the Bradford assay. The Coomassie Blue (CB)‐stained blots are also shown to indicate loading. Middle: quantification of GAPDH/CB‐stained protein ratio, showing that GAPDH protein levels are not statistically altered by expression of the miRNAs. Bottom: quantification of FMRP protein level normalized against GAPDH level.

-

BMSC1 cells lack detectable expression of Fx‐mir miRNAs. The expression levels of miR‐743b‐3p, miR‐878, and miR‐880‐3p in MSC1 cells and postnatal day (P) 10 mouse testes assayed by TaqMan‐qPCR analysis. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

-

C, DTaqMan‐qPCR analysis of miR‐465a, miR‐878, and miR‐881 expression levels in P19 and MSC1 cells transfected with indicated Fx‐mir miRNA precursors. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

Given that several Fx‐mir family members are primarily expressed in SCs (see below), we examined the effect of selected Fx‐mir miRNAs in MSC1, an established Sertoli cell line that has been used extensively in previous studies to analyze gene regulation in SCs 27, 40, 41. MSC1 cells do not express Fx‐mir family members (Fig EV2B), consistent with the fact that several SC‐enriched genes are turned off when SCs are established in culture 42, 43. However, the MSC1 cell line maintains many characteristics of SCs 42, 44, and its low/undetectable expression of Fx‐mir miRNAs allowed us to take a gain‐of‐function approach to analyze the function of Fx‐mir miRNAs in SCs. Transfection analysis in MSC1 cells revealed that several of the miRNAs we tested downregulated Fmr1 3′UTR‐driven reporter expression (Fig 2D). However, two of the miRNAs that repressed Fmr1 reporter expression in P19 cells—miR‐881 and miR‐465a (Fig 2B)—did not have a significant effect when force expressed in MSC1 cells (Fig 2D). This is not because MSC1 cells express endogenous miR‐881 and miR‐465a; indeed, neither MSC1 nor P19 cells express detectable levels of these miRNAs (Fig EV2C and D). Transfection of miR‐881 and miR‐465a precursors generated levels of these miRNAs in MSC1 cells similar to that of a Fx‐mir family member (miR‐878) that does downregulate the Fmr1 reporter (Figs 2D and EV2D), indicating that the lack of effect of miR‐881 and miR‐465a on the reporter in MSC1 cells is not due to low expression. The explanation we favor is that cell type‐specific factors are responsible for the differential activity of these miRNAs in P19 and MSC1 cells. As precedence for this, a recent study identified tissue‐specific miRNA‐silencing complexes 45.

Figure EV3A shows the high‐confidence binding sites for Fx‐mir family members predicted to target the Fmr1 3′UTR. While these predicted binding sites lie throughout the length of the Fmr1 3′UTR, they tend to be clustered in three regions. The specific sequences of some of these predicted binding sites and their complementarity with specific Fx‐mir miRNAs are shown in Fig EV3B. To test their functionality, we mutated the candidate miRNA‐binding sites for three miRNAs in the Fx‐mir cluster that downregulated Fmr1 3′UTR‐mediated reporter expression in both MSC1 and P19 cells (Figs 2B and D). All eight nucleotides complementary with the miRNA seed region and beyond were mutated (two in a given mutant construct) to fully analyze the contribution of the seed complementarity region. Figure 2E and F show the data for miR‐878 and miR‐880‐3p, both of which have only one strong predicted binding site in Fmr1 3′UTR. Gain‐of‐function studies with their respective miRNA precursors showed that 3 of the 4 miR‐878 mutants had a statistically significant reduction in miRNA‐mediated repression of reporter activity. The M3 and M2 mutants exhibited an almost complete loss of repression in response to the miR‐878 and miR‐880‐3p precursors, respectively. Together, this provided strong evidence that miR‐878 and miR‐880‐3p directly target Fmr1. miR‐743b‐3p has three predicted binding sites in the Fmr1 3′UTR (Fig EV3A); we made several mutations in the two predicted binding sites with stronger prediction scores [named “264 nt” and “1,482 nt”, based on their position within the 3′UTR (Table EV1)]. None of these mutants strongly reduced responsiveness to miR‐743b‐3p (Fig EV3C), raising the possibility that these two sites act redundantly. To test this, we generated a 264/1,482 double mutant and found it almost completely lost its ability to respond to miR‐743b‐3p (Fig 2G). This indicated that miR‐743b‐3p acts through two partially redundant binding sites in the Fmr1 3′UTR to repress Fmr1 expression.

Figure EV3. Fx‐mir‐binding sites in the Fmr1 3′UTR.

- Location of Fx‐mir miRNA‐binding sites, as predicted by microRNA.org. Most Fx‐mir miRNAs have only one predicted binding site. miR‐743b‐3p has three predicted binding sites (starting at positions 264, 1,368, and 1,482 nt relative to the beginning of the 3′UTR), while miR‐878 has two predicted binding sites (positions 357 and 2,225).

- Predicted base pairing between the indicated mature Fx‐mir miRNAs with their predicted binding sites in the mouse Fmr1 3′UTR. The seed region of the miRNA is indicated in red. The Fmr1 3′UTR is presented in the 5′ to 3′ orientation while the miRNAs are in the 3′ to 5′ orientation.

- Left: Two predicted binding sites of miR‐743b‐3p in the Fmr1 3′UTR act redundantly. miR‐743b‐3p‐binding site mutants in the 3′UTR of Fmr1 are shown. Right: luciferase analysis of MSC1 cells co‐transfected with (i) a miRNA precursor or a negative‐control scrambled miRNA precursor and (ii) the pMIR luciferase reporter with the wild‐type version of the mouse Fmr1 3′UTR or mutant versions with the indicated predicted miRNA‐binding site mutations. The binding site mutants were generated for miR‐743b‐3p sites at 264 nt and 1,482 nt. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

- Several Fx‐mir miRNAs are expressed in GS cells. TaqMan‐qPCR analysis of the expression of Fx‐mir family members in GS cells. P5 testes are as a control. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

We next took a loss‐of‐function approach to validate that Fx‐mir family members regulate Fmr1. We screened for cell lines that express Fx‐mir family members and found that most cell lines lacked detectable expression (data not shown). The one exception was germline stem (GS) cells (Fig EV3D), a spermatogonial stem cell line that retains stem cell potential 46. Using miRNA competitors, we repressed Fx‐mir family members we found were expressed in GS cells. Reporter analysis revealed that repression of miR‐465a and miR‐743b‐3p elevated the expression of the Fmr1‐driven reporter (Fig 2H), confirming our gain‐of‐function evidence that these miRNAs target Fmr1 (Figs 2B–D). In contrast, Fmr1‐driven reporter expression was not significantly affected by repression of miR‐878 and miR‐880‐3p, perhaps because these miRNAs can act redundantly as suggested by our miRNA mixing experiments shown below. We did not perform further experiments with GS cells as they exhibit inefficient transfection efficiency (data not shown) 47.

Mouse Fx‐mir miRNAs exhibit developmentally regulated expression in SCs

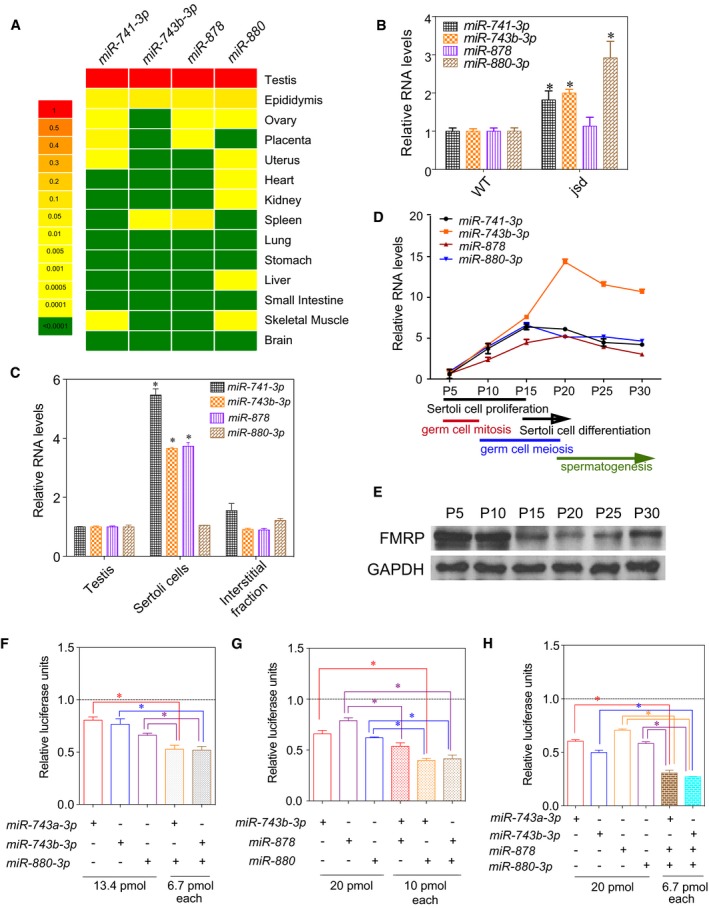

In what biological context does the Fx‐mir cluster function to regulate Fmr1? It has been previously shown that many of the miRNAs in the Fx‐mir cluster exhibit a testis‐preferential or testis‐specific expression pattern 48, 49, 50. To examine their expression pattern in more detail, we chose to focus on four Fx‐mir family members targeting Fmr1. Three of these miRNAs (miR‐743b‐3p, miR‐878, and miR‐880‐3p) have the highest prediction scores for targeting Fmr1 of all Fx‐mir family members (Table EV1) and the fourth miRNA (miR‐741‐3p) exhibited strong down‐regulation of an Fmr1 3′UTR reporter (Fig 2B), despite having a low prediction score (Table EV1). We found that all four of these miRNAs are most highly expressed in the testis (Fig 3A), confirming previous reports 51, 52. These miRNAs were also expressed in the epididymis (the organ where sperm mature and are stored), but at ~10‐fold lower level than in the testis (Fig 3A). We also tested members of the rat Fx‐mir cluster and found they also exhibited testes‐enriched expression (Fig EV4A).

Figure 3. Developmentally regulated expression and additive action of mouse Fx‐mir family members.

-

AThe steady‐state levels of Fx‐mir miRNAs in the indicated adult mouse tissues, as assessed by TaqMan‐qPCR analysis. U6 levels were used to normalize miRNA values.

-

BTaqMan‐qPCR analysis of testes from three jsd mice and three control littermate mice. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

-

CFx‐mir miRNA levels in total mouse testis and different testicular cell fractions assessed by TaqMan‐qPCR analysis. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

-

DTaqMan‐qPCR analysis of testes from the indicated postnatal time points (n = 3 for each time point). U6 levels were used to normalize miRNA values.

-

EWestern blot analysis of mice testes from the indicated postnatal time points.

-

F–HLuciferase analysis of MSC1 cells co‐transfected with the pMIR‐luciferase reporter harboring the mouse Fmr1 3′UTR and the indicated Fx‐mir miRNAs (n = 3). The luciferase activity of cells transfected with a negative‐control scrambled precursor is set to 1. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

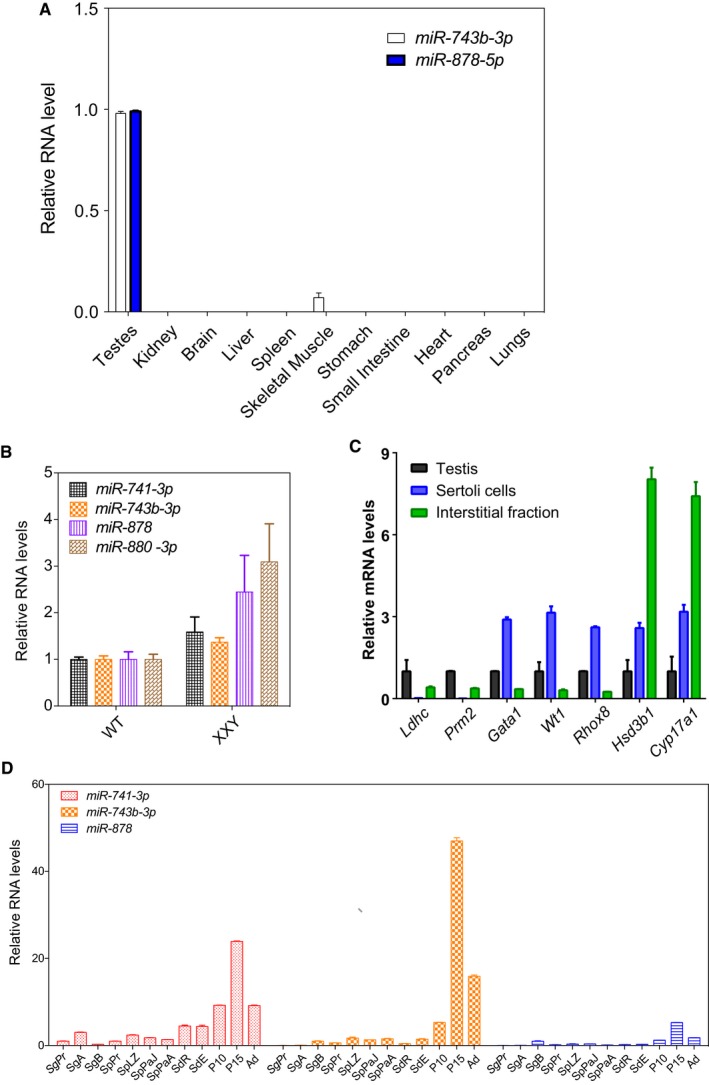

Figure EV4. Expression pattern of selected Fx‐mir family members.

- Fx‐mir miRNA levels in different adult rat tissues assessed by TaqMan‐qPCR analysis. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

- Fx‐mir levels in the testes of germ cell‐deficient Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) mice. TaqMan‐qPCR analysis of three XXY mice and three control littermate mice are presented. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

- qPCR analysis of germ cell, Leydig, and SC marker genes in cell fractions isolated from mouse testis. The mRNA values were normalized to L19, and the expression values from total testis are considered as 1.

- Fx‐mir miRNA levels in total mouse testis and different testicular cell fractions assessed by TaqMan‐qPCR analysis. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization. SgPr, primitive type A spermatogonia; SgA, type A spermatogonia; SgB, type B spermatogonia; SpPr, preleptotene spermatocytes; SpLZ, leptotene and zygotene spermatocytes; SpPaJ, pachytene spermatocytes from juvenile mice at postnatal day 18; SpPaA, pachytene spermatocytes from adult mice; SdR, round spermatids; SdE, elongated spermatids and residual bodies.

The testes‐enriched expression of members of the Fx‐mir cluster raises the possibility it regulates Fmr1 in this organ. Consistent with this possibility, FXS patients lacking FMR1 expression have macroorchidism and defects in spermatogenesis 53, 54. These defects are recapitulated in Fmr1‐null mice 55. While the underlying cellular mechanism for the generation of large testes is not known, a likely possibility is SC over‐expansion, based on finding that Fmr1‐null mice have hyper‐proliferative SCs 56. Also consistent with this possibility is the finding that the protein product of Fmr1—FMRP—is highly expressed in SCs in both mice and humans 57, 58. Thus, in order for Fx‐mir family members to regulate Fmr1 in a physiological context, it is critical that these miRNAs are also expressed in SCs. To assess this, we used two approaches. First, we assayed their expression in germ cell‐deficient mice. If they are primarily expressed in SCs, their testicular expression should be increased in these mice, as somatic cells are enriched in germ cell‐deficient testes. Indeed, 3 of 4 of the Fx‐mir miRNAs we tested exhibited elevated expression in germ cell‐deficient testes relative to control testes (Figs 3B and EV4B). Second, we purified enriched SCs and found that they expressed high levels of Fx‐mir miRNAs (Figs 3C and EV4C). Three of the 4 miRNAs are expressed at higher levels in purified SCs than total testis, indicating that SCs are the primary site of their expression. We note that it has been previously reported that Fx‐mir miRNAs are expressed in germ cell‐enriched fractions 48, 52, 59, a finding we reproduced, but we found that expression in the germ cell fractions was much lower than in the total testis fraction (Fig EV4D). Whether this low signal represents trace Fx‐mir expression in germ cells or contamination of the germ cell fraction with Fx‐mir‐expressing SCs remains to be determined.

SCs are nurse cells in contact with all stages of germ cells and are critical for virtually all phases of spermatogenesis 60, 61. SCs undergo a series of programmed events during the first wave of spermatogenesis; thus, we next examined the expression of Fx‐mir miRNAs during this developmental time window (Fig 3D). We found that all 4 mRNAs we tested are expressed at low level at P5, when both SCs and germ cells are undergoing rapid proliferation. Their expression dramatically elevates at later time points (Fig 3D), coincident with a drop in FMRP protein expression (Fig 3E). miR‐741‐3p and miR‐880‐3p reach their highest expression at P15, a time point that coincides with the cessation of SC proliferation and the initiation of SC terminal maturation 62, 63. Thus, these two miRNAs are candidates to regulate the expression of mRNAs important for this proliferation‐to‐maturation transition phase of SC development. This possibility is particularly enticing given that SCs are known to undergo hyperproliferation in Fmr1‐null mice 56. miR‐743b‐3p and miR‐878 exhibited peak expression slightly later, at P20, when SCs undergo further maturation and germ cells initiate differentiation by forming round spermatids. Given that germ cells are in direct contact with SCs 64, this supports a model in which miR‐743b‐3p and miR‐878 regulate gene expression in SCs to influence germ cell differentiation. In support of the possibility that the Fx‐mir cluster is important for spermatogenesis, a recent study reported that several human FX‐MIR family members—including miR‐891b, miR‐892b, miR‐892a, miR‐888, and miR‐890—are dysregulated in men with asthenozoospermia 65.

Mouse Fx‐mir miRNAs act additively to repress Fmr1 expression

miRNAs typically downregulate their mRNA targets by only ~20–40% 66. To amplify their regulatory effect, several miRNAs must work in conjunction to strongly downregulate a given target mRNA. Our finding that several Fx‐mir family members that target Fmr1 3′UTR (Fig EV3A) are co‐expressed in SCs during the same developmental window (Figs 3C and D) raised the possibility that they work together to strongly regulate Fmr1. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether combinations of Fx‐mir family members have greater effects than do single‐family members. In support, we found that several Fx‐mir miRNAs had additive effects (Figs 3F and G). Of note, an additive effect was observed even though we treated the cells with only a half‐dose (6.7 pmol) of each miRNA when provided in combination, as compared to the full dose (13.4 pmol) when provided singly (Fig 3F). Given that miR‐878, miR‐743b‐3p, and miR‐880 all exhibited additive effects in various combinations (Fig 3G), we also tested a combination of all three of these miRNAs and found that this elicited a very strong repression (~80%) that was much more pronounced than elicited by the individual miRNAs (Fig 3H).

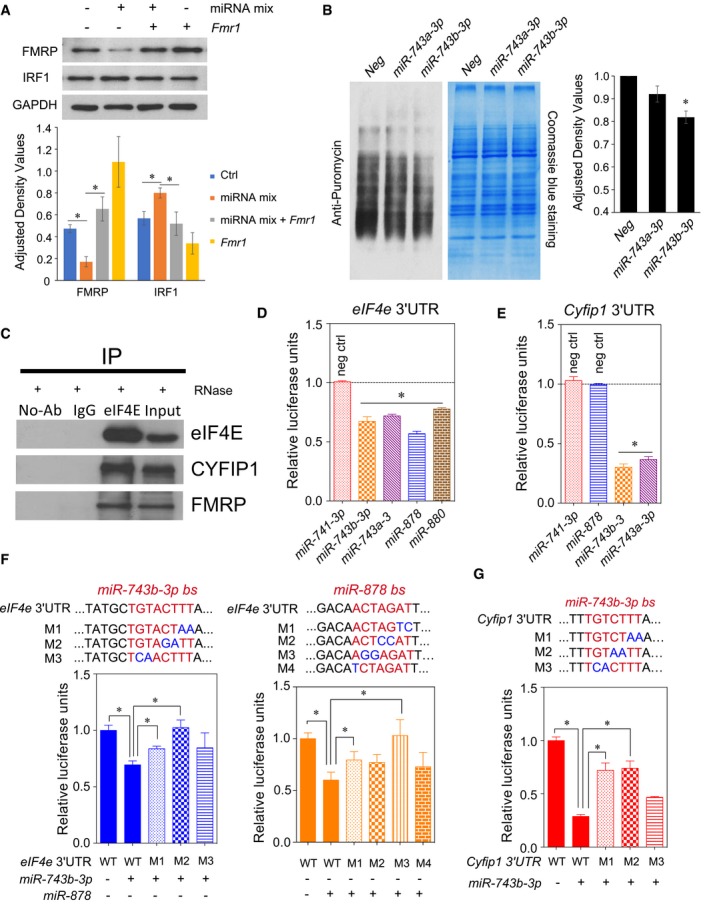

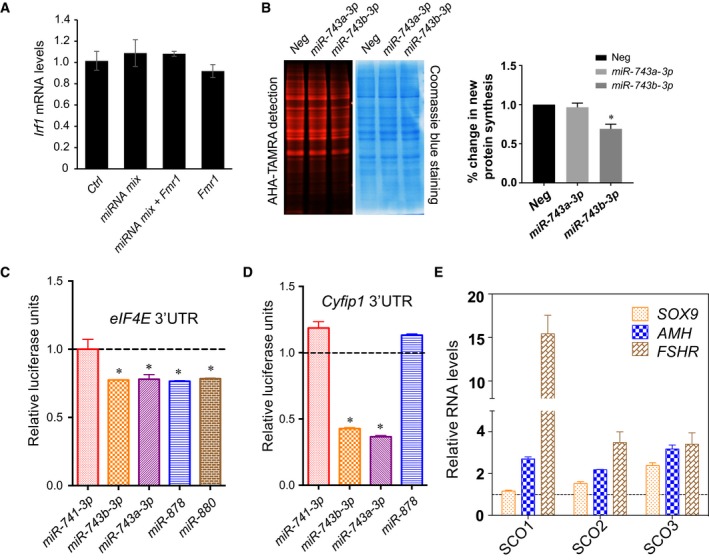

Mouse Fx‐mir miRNAs regulate the FMRP‐eIF4E‐CYFIP1 translational regulatory complex

Having demonstrated that Fx‐mir family members downregulate Fmr1 expression, we next asked whether Fx‐mir family members can affect Fmr1 function. Given that the protein product of Fmr1, FMRP, is a translation repressor, we examined whether Fx‐mir miRNAs affect this function. We chose to examine the FMRP‐regulated gene, interferon regulatory factor 1 (Irf1), as it encodes a protein involved in spermatogenesis: It promotes germ cell survival in vitro and in vivo, and functions as a pro‐mitogenic factor in spermatogonia 67. Transfection analysis showed that forced expression of a pool of three Fx‐mir miRNAs downregulated FMRP protein level and increased IRF1 protein level (Fig 4A). Irf1 mRNA level was not significantly altered by this treatment (Fig EV5A), consistent with FMRP acting as a translational repressor 67. The upregulation of IRF1 was reversed by FMRP overexpression (Fig 4A). Taken together, these data suggest that Fx‐mir family members regulate FMRP levels, which, in turn, allow them to regulate FMRP function.

Figure 4. Fx‐mir miRNAs target translation regulatory factors.

-

AFx‐mir miRNAs repress FMRP function. Top, Western blot analysis of P19 cells transfected with a pool of Fx‐mir miRNAs targeting Fmr1 (miR‐743b‐3p, miR‐878, and miR‐880‐3p) and/or a Fmr1 expression vector. Bottom, quantification of the Western blot.

-

BmiR‐743b‐3p reduces protein synthesis. Left, P19 cells were transfected with negative‐control miRNAs or the indicated Fx‐mir miRNAs 42 h prior to the addition of puromycin in the culture medium. The blot was probed with an antibody to puromycin (which detects newly synthesized proteins) and subsequently stained with Coomassie Blue to control for loading. Right, quantification of puromycin incorporation.

-

CFMRP, eIF4E, and CYFIP1 interact in the testis. Immunoprecipitation of testis lysates with eIF4E or IgG control antibody, followed by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The testis lysate was incubated with RNase A to exclude RNA‐dependent protein–protein interactions. The input sample is the whole testes lysate (5% relative to volume used for immunoprecipitation).

-

D, EFx‐mir miRNAs target the translation factors eIF4E and CYFIP1. Luciferase analysis of MSC1 cells co‐transfected with the pMIR‐luciferase reporter harboring the indicated full‐length 3′UTR and the indicated Fx‐mir miRNAs. miR‐741‐3p was used to demonstrate specificity for regulation of Eif4e, as this miRNA does not have a predicted binding site in Eif4e 3′UTR. Likewise, miR‐741‐3p and miR‐878 were used to demonstrate specificity for Cyfip1, as these miRNAs do not have binding sites in the Cyfip1 3′UTR. The luciferase activity of cells transfected with a negative‐control scrambled precursor is set to 1. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

-

F, GMutagenesis analysis demonstrates that Eif4e and Cyfip1 mRNA are Fx‐mir direct targets. Luciferase analysis of MSC1 cells co‐transfected with (i) a miRNA precursor or a negative‐control scrambled miRNA precursor and (ii) the pMIR‐luciferase reporter harboring the wild‐type version of the mouse Eif4e and Cyfip1 3′UTR or mutant versions with the indicated predicted miRNA‐binding site (bs) mutations. The seed sequences are depicted in red and the mutations are in blue. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

Figure EV5. Fx‐mir miRNAs regulate factors that form a translation regulatory complex.

- qPCR analyses of Irf1 in P19 cells transfected with Fx‐mir miRNA mix and/or Fmr1 overexpression (OE) vector. The mRNA values were normalized to L19. All values are relative to P19 cells co‐transfected with a scrambled miRNA precursor and OE empty vector, which is set to 1.

- miR‐743b‐3p reduces proteins synthesis. Left: P19 cells were transfected with negative‐control miRNAs or the indicated Fx‐mir precursor miRNAs 48 h prior to the addition of Click‐iT AHA in the culture medium. Newly synthesized proteins labeled with Click‐iT AHA were conjugated with the TAMRA and detected using 532 nm excitation. The gel was then stained with Coomassie Blue to assay protein loading. Right: % change in new protein synthesis.

- Fx‐mir miRNAs target Eif4e. Luciferase analysis of P19 cells co‐transfected with pMIR luciferase reporter harboring mouse Eif4e 3′UTR and the indicated Fx‐mir miRNAs or a scrambled miRNA precursor that served as control. miR‐741‐3p was used as a control to demonstrate specificity, as it does not have a predicted binding site in Eif4e 3′UTR. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

- Fx‐mir miRNAs target Cyfip1. Luciferase analysis of P19 cells co‐transfected with pMIR luciferase reporter harboring mouse Cyfip1 3′UTR and the indicated Fx‐mir miRNAs or a scrambled miRNA precursor that served as control. miR‐741‐3p and miR‐878 were to demonstrate specificity, as they do not have binding sites in Cyfip1 3′UTR. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

- SCO patient testes express elevated levels of Sertoli cell marker genes. qPCR analysis of SOX9, AMH, and FSHR (SC marker genes) in SCO patient samples was performed. The mRNA values were normalized to GAPDH, and the expression values from controls are considered as 1.

Given that FMRP translationally regulates hundreds of mRNAs 32, 33, 34, we hypothesized that Fx‐mir family members influence translation globally. To test this hypothesis, we used SUnSET, a nonradioactive puromycin end‐labeling assay that quantifies global protein synthesis 68. Using this approach, we found that forced expression of miR‐743b‐3p significantly decreased protein synthesis (Fig 4B). Two lines of evidence argue against this being the result of cellular toxicity. First, P19 viable cell count and morphology were not significantly affected by forced miR‐743b‐3p expression (data not shown). Second, transfection of neither a related miRNA (miR‐743a‐3p), nor a scramble‐sequence negative‐control miRNA, significantly affected global translation (Fig 4B). As an independent approach to assess the effect of miR‐743b‐3p on translation, we used Click‐iT metabolic labeling, which labels newly synthesized proteins with the methionine analog, L‐azidohomoalanine (AHA). This analysis verified that miR‐743b‐3p significantly represses translation (Fig EV5B). While the effect of miR‐743b‐3p on global translation rate was relatively modest (~20%), it has the potential to be physiologically relevant, as the translation rate of large batteries of mRNAs would presumably be affected. If, instead, miR‐743b‐3p exerted strong translational silencing, this would be expected to instead cause toxicity, as does strong translational silencing during viral infections 69.

In neurons, FMRP regulates translation through forming a translational regulatory complex with two other proteins: eIF4E and CYFIP1 70. eIF4E is a rate‐limiting translation initiation factor essential for translation, while CYFIP1 is an eIF4E‐binding protein that represses translation 70, 71. To test whether this complex exists in the testis, we performed co‐immunoprecipitation experiments. In support, we found both FMRP and CYFIP1 were immunoprecipitated from testes extracts by an eIF4E antibody but not control IgG or no antibody (Fig 4C). We conclude that FMRP, eIF4E, and CYFIP1 interact together in the testes just as they do in neurons.

In silico analysis showed that the 3′UTR regions of Eif4e and Cyfip1 are predicted to be targeted by several Fx‐mir family members (Table EV3), and thus, we next tested whether Fx‐mir miRNAs regulate eIF4E and CYFIP1. After cloning their full‐length 3′UTRs into the pMIR‐luciferase vector, we performed transfection analysis in MSC1 Sertoli cells and found that luciferase activity from the reporter harboring either the Eif4e 3′UTR or Cyfip1 3′UTR was repressed by several Fx‐mir family members (Fig 4D and E). As negative controls, we tested miRNAs not predicted to target these two 3′UTRs and found that, indeed, they had no significant effects (Fig 4D and E). Analogous experiments performed in P19 cells revealed similar effects as in MSC1 cells (Fig EV5C and D), suggesting that these miRNAs have a broad ability to regulate Eif4e and Cyfip1. Mutagenesis of the miR‐743b‐3p and miR‐878 predicted binding sites in the mouse Eif4e 3′UTR relieved miRNA‐mediated repression (Fig 4F). Many mutants exerted statistically significant effects, while others exerted a trend toward relieved repression. The same was observed for the miR‐743b‐3p predicted binding site in the Cyfip1 3′UTR (Fig 4G). We conclude that some Fx‐mir family members directly target not only Fmr1, but also Eif4e and Cyfip1. This finding, coupled with the expression pattern of these miRNAs in SCs, supports a model in which specific Fx‐mir family members modulate the translation rate of batteries of mRNAs that are critical to shift SCs from a proliferative to differentiated cell state.

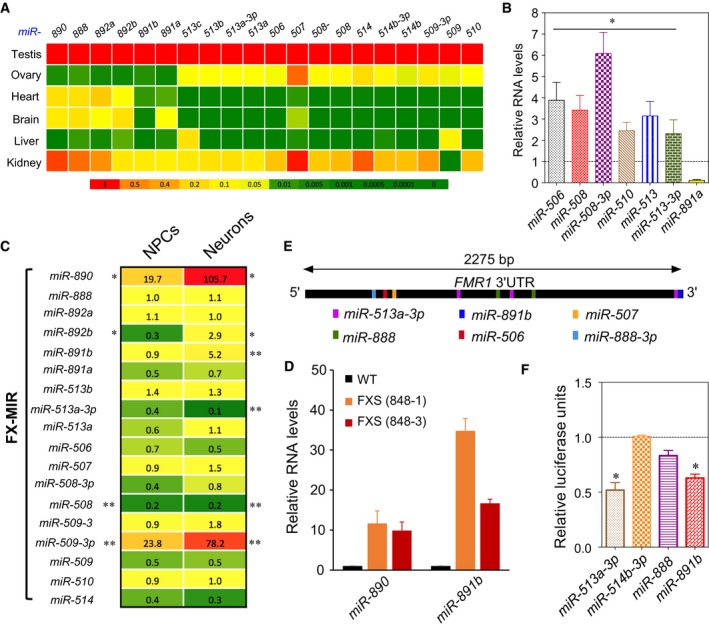

The human FX‐MIR cluster largely shares the expression pattern of the mouse Fx‐mir cluster

We next turned our attention to the human FX‐MIR cluster. To assess its expression characteristics, we examined the levels of 20 mature miRNAs derived from this cluster in human tissues. We found that all 20 of these human FX‐MIR miRNAs are highly expressed in the testis (Fig 5A), just as we showed was the case for mouse and rat Fx‐mir miRNAs (Figs 3A and EV4A). However, the human FX‐MIR cluster differs from the mouse Fx‐mir cluster in being expressed in other adult tissues (Fig 5A). miRNAs expressed from the 5′ region of the FX‐MIR cluster tend to be expressed in ovary, while miRNAs expressed from the 3′ region tend to be expressed in brain and heart. Both 5′ and 3′ miRNAs are expressed in kidney. Together, this indicates that while high testis expression is a conserved feature of the Fx‐mir cluster, the human version of this cluster has diversified its expression, including the brain, where FMR1 is highly expressed 57.

Figure 5. Expression and function of human FX‐MIR miRNAs.

- Heat map depicting the steady‐state levels of FX‐MIR miRNAs in the indicated adult human tissues, as assessed by TaqMan‐qPCR analysis. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

- FX‐MIR miRNAs are enriched in human Sertoli cell‐only (SCO) patient samples. Average values from TaqMan‐qPCR analysis of testes biopsies from three SCO patients and three controls. The control values are set as 1. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

- Heat map depicting the relative expression (fold difference) of FX‐MIR family members in FXS patient versus healthy control iPSC‐derived NPC lines and neurons. *0.05 < P < 0.1; **P < 0.05.

- Expression of selected human FX‐MIR miRNAs in FXS cells. TaqMan‐qPCR analysis of human miR‐890 and miR‐891b in neurons differentiated from iPSC lines generated from FXS patients and control individuals. The expression level in control cells is set at a value of 1. U6 snRNA levels were used for normalization.

- Location of human FX‐MIR‐binding sites along the length of the human FMR1 3′UTR.

- Evidence that human FX‐MIR miRNAs repress human FMR1 expression. Luciferase analysis of HeLa cells co‐transfected with the pMIR‐luciferase reporter harboring the human full‐length FMR1 3′UTR and the indicated FX‐MIR miRNAs (n = 3). The luciferase activity of cells transfected with a negative‐control scrambled precursor is set to 1. A Renilla luciferase vector was co‐transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency.

Given that mouse Fx‐mir miRNAs are expressed in SCs (Fig 3B and C), we assessed whether this might also be the case for human FX‐MIR miRNAs. Toward this end, we obtained RNA from Sertoli cell‐only (SCO) patients, who largely or completely lack germ cells in their seminiferous tubules. If human FX‐MIR family members are expressed in SCs, their expression relative to total testis RNA would be expected to be higher in SCO testes than in normal testes. Consistent with this, we found that 6 of the 7 FX‐MIR family members we tested exhibited elevated (~2‐ to 6‐fold) expression in SCO testes as compared to normal testes (Fig 5B). As a positive control, we tested the expression of SC markers (FSHR, AMH, SOX9) and found they were also upregulated in SCO testes (Fig EV5E). These data strongly suggest that FX‐MIR miRNAs are most prominently expressed in SCs and/or other somatic cells in the human testis.

Given that some human FX‐MIR family members are modestly expressed in brain (Fig 5A), this raised the possibility that the FX‐MIR cluster has a role in FXS. Because the FX‐MIR cluster is directly adjacent to FMR1, the latter of which is methylated and transcriptionally inactivated in neurons in FXS 72, this raised the possibility that the inactive chromatin at the FMR1 locus has spread to the FX‐MIR cluster and thereby repressed the expression of its miRNAs in FXS. To test this hypothesis, we used NanoString Technology to assay the expression of the FX‐MIR miRNAs in neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) and differentiated neurons derived from iPSC lines generated from FXS patients and control individuals. This analysis showed that several FX‐MIR miRNAs had significantly dysregulated expression in FXS NPCs and neurons (Fig 5C and D, and Appendix Table S3). However, the expression of the FX‐MIR cluster was not broadly repressed, strongly suggesting that the inactive chromatin from the FMR1 locus had not spread to the FX‐MIR cluster. Indeed, two FX‐MIR miRNAs (miR‐509‐3p and miR‐890) had significantly elevated expression in FXS NPCs relative to control NPCs. A similar trend of regulation was seen in neurons where FX‐MIR family members were both downregulated and upregulated. As observed in NPCs, neurons upregulated miR‐509‐3p and miR‐890 (by ~78‐fold and ~106‐fold, respectively). The finding that a subset of FX‐MIR miRNAs are dysregulated in FXS raises the interesting possibility that these particular miRNAs have a role in FXS.

The human FX‐MIR cluster targets FMR1

As described above, the sequences of the miRNAs in the human FX‐MIR cluster and mouse Fx‐mir cluster are extremely divergent, such that only one clear miRNA ortholog can be discerned (Appendix Fig S1B). This presented an opportunity to ask a unique question—has the FX‐MIR cluster retained the ability to target translation regulatory factors despite the rapid divergence in the sequence of the miRNAs it encodes? As a first step to assess whether members of the human FX‐MIR cluster target FMR1, we screened the 2,588 candidate human miRNAs available in miRBase for their ability to target FMR1 using the miRNA target prediction programs, microRNA.org and TargetScan. This revealed that 2 of the 15 human miRNAs exhibiting the highest prediction scores for targeting FMR1 are encoded by the human FX‐MIR cluster (Appendix Table S1). In total, FMR1 is predicted to be targeted by 13 human FX‐MIR miRNAs (microRNA.org), six of which are high‐confidence targets with strong prediction scores (both microRNA.org and TargetScan), and multiple predicted binding sites (Fig 5E, Table EV4). The total number of predicted FX‐MIR miRNA‐binding sites in the FMR1 3′UTR is 26.

To experimentally test the validity of this computational analysis, we cloned the full‐length human FMR1 3′UTR into a luciferase reporter vector and tested the activity of three human FX‐MIR family members. We found that two of them—miR‐513a‐3p and miR‐891b—elicited statistically significant repression in luciferase expression from the reporter vector harboring the human FMR1 3′UTR (Fig 5F). The third miRNA, miR‐888, triggered a trend toward reduced expression but was not statistically significant. Together with our computational analysis, the data indicate that the FX‐MIR cluster has retained its ability to regulate FMR1 despite its rapid evolution.

As detailed above, we obtained several lines of evidence that the Fragile‐X gene—Fmr1—is a strongly favored target of miRNAs encoded by the mouse Fx‐mir cluster. To assess whether the same is the case for the human FX‐MIR cluster, we first examined three genes (SOX9, FSHR, and GJA1) known to be highly expressed in human SCs 73, 74, 75, the main cell type that expresses several FX‐MIR family members (Fig 5B). As shown in Table EV5, the mRNA encoded by these three SC‐expressed genes all had fewer predicted binding sites for the 24 known FX‐MIR family members than did FMR1 (Table EV5). We also examined the top 20 genes enriched for expression in human neonatal SCs, as defined by single‐cell RNAseq analysis (Song et al, manuscript in preparation), and found that most of the mRNAs from these genes had far fewer predicted FX‐MIR family member‐binding sites than did FMR1 mRNA (Table EV5). The only exception—CALD1—had 12 predicted FX‐MIR‐binding sites, the same number as for FMR1. Together, these data support the notion that, like the mouse Fx‐mir cluster, the human FX‐MIR cluster has a predilection for targeting FMR1.

Discussion

In this study, we report that the Fragile‐X gene, FMR1, is targeted for repression by a large cohort of miRNAs expressed from a miRNA cluster adjacent to it. This property appears to be conserved, as we found that the Fx‐mir cluster is directly adjacent to Fmr1 across all placental mammals we examined. This predilection for targeting Fmr1 was unexpected given that miRNAs function in trans and thus have the potential to target virtually any gene in the genome.

Why is Fmr1 a frequent target of a miRNA cluster adjacent to it? One possibility is that close proximity allows for common regulatory elements to drive the coordinated expression of Fmr1 and the Fx‐mir cluster, which, in turn, would allow for more efficient regulation. Consistent with this possibility, Fmr1 and Fx‐mir family members have similar expression patterns. Fmr1 is highly expressed in mouse testis, which is also the primary site of Fx‐mir expression 48, 76, 77. Likewise, in humans, both FMRP and FX‐MIR miRNAs are expressed in the brain and the testis 78. Also, consistent with the possibility of common regulatory elements driving their expression, Fmr1 and the Fx‐mir miRNA cluster have a head‐to‐head configuration. Strikingly, all the miRNAs in both the human FX‐MIR and mouse Fx‐mir clusters exhibit the same transcriptional orientation, which is consistent with the possibility that many or all of them are derived from a long primary transcript driven by a single promoter. This architecture allows for a dedicated regulatory domain housing enhancer elements that can act on both Fmr1 and the Fx‐mir cluster. As precedent for the notion of common regulatory elements driving non‐coding and coding RNAs, Hu et al 79 identified bidirectional promoters driving the transcription of mRNAs and lncRNAs in opposite directions in neurons. While co‐expression of the Fx‐mir cluster and Fmr1 allows the former to regulate the latter in the same cell types, we suggest that the Fx‐mir cluster is also likely to be independently regulated from Fmr1. Layering independent regulation on top of coordinate regulation would allow members of the Fx‐mir cluster to modulate Fmr1 expression in response to specific stimuli.

A non‐mutually exclusive explanation for the propensity of the Fx‐mir cluster to target Fmr1 is the Fx‐mir cluster originated from an ancient Fmr1 gene. In support of this possibility, the primordial Fmr1 gene is known to have spawned duplicate copies of itself. Several autosomal paralogs of Fmr1 currently exist in vertebrate genomes 80. We suggest that in addition to dispersing paralogs to other chromosomes, a primordial Fmr1 gene also generated a duplicated copy directly adjacent to itself. Duplicated copies of genes often are generated in tandem arrays through the process of “unequal crossing over”, a type of gene duplication event that occurs at only low frequency during mitosis and meiosis, but once it occurs, it can be selected for over evolutionary time. If Fmr1 was duplicated in this manner, one copy may have degenerated into an expressed pseudogene that lost its ability to generate a protein and acquired an ability to generate miRNAs. In favor of this “miRNA birth” hypothesis, miRNAs have been shown to form relatively easily during short periods of evolutionary time 18. An attractive model is the Fx‐mir cluster was derived from a duplicated copy of the Fmr1 gene transcribed in the antisense direction, as such miRNAs would automatically exhibit a predilection for targeting Fmr1 because they would be complementary to Fmr1 mRNA. Regardless of the mechanism(s) responsible for Fmr1 and Fx‐mir occupying the same genomic neighborhood, once this genomic arrangement was established, it may have been maintained by a mechanism that prevents genomic rearrangements. Such a rearrangement‐suppression mechanism has been postulated to be responsible for Hox‐regulatory miRNAs being retained in Hox gene clusters in multiple species 81. Indeed, there is evidence that miRNAs tend to exhibit conserved gene order relative to protein‐coding genes 82. This conservation may serve to maintain an optimal genomic environment for the expression and function of miRNAs.

Why does the Fx‐mir cluster harbor such a large number of miRNAs? One possibility is this cluster expanded as a result of selection to exert strong regulation on Fmr1 and other key target mRNAs. Single miRNAs typically only downregulate their mRNA targets by ~20–40%, and thus, multiple miRNAs are typically required to confer stronger regulation 66. Indeed, we found that combinations of two Fx‐mir family members more strongly repressed Fmr1 3′UTR‐driven reporter expression than did single‐family members; a combination of 3 Fx‐mir family members conferred particularly strong (~80%) downregulation. Previous studies have shown that more pronounced regulation is conferred when miRNA‐binding sites are in close proximity (< 40 nt) 82, 83. Thus, it is of interest that we observed additive effects of multiple Fx‐mir family members even though their binding sites are relatively far apart in the Fmr1 3′UTR (between 94 and 625 nt apart; see the Results section). The ability of combinations of Fx‐mir miRNAs to strongly regulate Fmr1 expression raises the possibility that these miRNAs may not only serve as “fine tuners”, but also serve as biological switches. In particular, Fmr1 may be a key target that serves in such circuitry, as we found that Fmr1 3′UTR‐mediated reporter expression was repressed by very low doses (0.6 pmol) of some Fx‐mir family members (miR‐878 and miR‐880‐3p; data not shown).

A conserved feature of the Fx‐mir cluster is its high expression in the testis. Intriguingly, we obtained evidence that the primary cell type expressing the Fx‐mir cluster in both humans and mice is the SC, which is a large somatic cell in direct contact with all stages of developing male germ cells. SCs provide factors and an appropriate niche that support all steps of spermatogenesis. We found that two mouse Fx‐mir family members, miR‐741‐3p and miR‐880‐3p, are most highly expressed when rodent SCs cease proliferation and undergo terminal maturation. Thus, these miRNAs are candidates to regulate the expression of key target mRNAs important for this proliferation‐to‐maturation transition phase of Sertoli cell development. Two other miRNAs in the mouse Fx‐mir cluster, miR‐878 and miR‐743b‐3p, display highest expression at a slightly later point of development—P20—when SCs undergo further maturation and the most advanced germ cells are undergoing the transition from meiosis to differentiation 79, 80. Other members of the Fx‐mir cluster, including miR‐743a‐3p and miR‐883a, have been shown to display peak expression during this same ~P15 to ~P20 time window 48, raising the possibility that many miRNAs from the Fx‐mir cluster cooperate to drive or fine‐tune events that occur during this critical somatic and germ cell developmental time period.

While rodents primarily express the Fx‐mir cluster in the testis, we found that humans express FX‐MIR cluster in other tissues, including the brain. It has been often noted that many genes are co‐expressed in the testes and the brain, but the evolutionary forces driving this expression pattern and the functional consequences of it are not known 84, 85. The expression of the FX‐MIR cluster in both brain and testis in humans is of interest given that its major target, FMR1, is particularly highly expressed in these two particular organs, as described above 78, 86. Thus, the FX‐MIR cluster may regulate translation in cells in both of these two organs through its ability to repress FMRP levels.

The rapid sequence divergence of the X‐linked Fx‐mir cluster is consistent with a wide body of work showing that X‐linked and testes‐expressed genes tend to undergo rapid evolution 76, 77, 78, 79, 80. Increasing evidence suggests that the testis is birthplace of many genes and has a permissive environment for gene expression and therefore has a particularly diverse transcriptome 40, 76. This is not restricted to protein‐coding genes, as studies have shown that miRNAs in their rapidly evolving phase also commonly exhibit restricted expression in the testis 81, 82, 83. Indeed, the Fx‐mir cluster appears to be fairly young, which may contribute to its rapid evolution.

The rapid evolution of the Fx‐mir cluster presents an interesting dilemma. While Fx‐mir sequence alterations permit the miRNAs expressed from this cluster to regulate new target mRNAs, how do they retain the ability to regulate previous critical mRNA targets? We suggest that in some cases, miRNAs and their critical targets undergo co‐evolution, such that sequence alterations in the miRNAs select for corresponding sequence alterations in the mRNA target to maintain sequence complementarity. In the case of coordinately regulated miRNA clusters such as the Fx‐mir cluster, a flexible approach may be used to achieve this goal, such as a “division of labor” approach in which “old” and “new” mRNA targets are regulated by different family members. In support, we found that many seemingly unrelated miRNAs in the human and mouse Fx‐mir clusters targeted Fmr1, raising the possibility that selective forces acting on independent miRNAs were responsible for maintaining Fmr1 regulation in the primate and rodent lineages. Thus, in spite of the rapid divergence of sequence, both the mouse and human Fx‐mir clusters are able to efficiently target Fmr1. Thus, the Fx‐mir cluster may be a useful model to study miRNA clusters at an intermediate point of evolution that are rapidly acquiring new mRNA targets (“new friends”) but also maintaining a subset of their old mRNA targets (“old friends”).

Functional conservation in the face of rapid sequence evolution is a growing theme in biology. For example, Ulitsky et al identified lincRNAs that have conserved roles in embryonic development in zebrafish and humans despite the fact they exhibit little sequence conservation between these two species 84. These lincRNAs maintain their location in the genomes of diverse species, just as we showed is the case for the rapidly evolving Fx‐mir cluster. Another example of maintenance of function in the face of sequence diversity is transcription factor cis‐regulatory elements, which have been shown to maintain the ability to regulate specific genes and transcriptional programs despite undergoing rapid changes in sequence 85. Indeed, retention of precise transcription factor binding sites appears to be the exception, rather than the rule, over evolutionary time. For example, the Endo16 promoter, while divergent in sequence in two sea urchin species, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus and Lytechinus variegatus, maintains its transcription pattern during larval development in these two species 86. Similarly, the enhancer elements in the even skipped locus in Drosophila and scavenger flies are highly divergent in sequence, yet they drive identical expression patterns in transgenic Drosophila embryos 87.

In conclusion, we have defined a new miRNA cluster and found that a large cohort of miRNAs expressed from this cluster target Fmr1, the gene directly adjacent to it in all placental mammals we examined. Several members of the Fx‐mir cluster target not only Fmr1, but also mRNAs encoding other proteins that form a regulatory complex with FMRP. This result, coupled with our finding that many members of the FX‐MIR cluster are expressed in human neurons and SCs, raises the possibility that one function of this miRNA cluster is to control the translation of batteries of mRNAs in these seemingly unrelated somatic cells. In the future, it will be important to determine the clinical consequences of dysregulated FX‐MIR expression.

Materials and Methods

Mammalian cell culture, transfections, and luciferase assays

MSC1 and HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% fetal calf serum, and 1× penicillin/streptomycin. P19 cells were grown in MEMα (Invitrogen), 10% fetal calf serum, and 1× penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). All cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. For transfection experiments, the cells were trypsinized and seeded in 24‐well plates at a density of ~50,000 cells per well. The cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. The transfections were carried out with 20 pmol of miRNA precursor, 20 ng of firefly luciferase vector, and 10 ng of the Renilla luciferase vector. Dual luciferase analysis (using a Renilla Luciferase vector for normalization) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Cat. no. E1960) on lysates prepared 24 h post‐transfection. Statistical significance was determined using the paired Student's t‐test.

Testis cell fractionation

Sertoli and interstitial cells were purified from testes as previously described 41. In brief, testes were decapsulated and the seminiferous tubules were allowed to settle in PBS, followed by incubation in collagenase (C2674; Sigma). After another round of settling, the pellet and supernatant were used as the source of SCs and interstitial (mainly Leydig) cells, respectively. To obtain enriched SCs, the pellet was resuspended in a solution containing 0.1% collagenase, 0.2% hyaluronidase (H6254; Sigma), 0.04% DNase I (D5025; Sigma), and 0.03% trypsin inhibitor (T6522; Sigma) in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) at 30°C for 40 min. The SCs were purged of contaminating germ cell by hypotonic shock (incubation in 1:7 diluted PBS for 3 min). To obtain enriched Leydig cells, the supernatant obtained after collagenase treatment was pelleted and subjected to the same hypotonic shock treatment as the SCs.

3′UTR cloning

The full‐length 3′UTR of Fmr1, Eif4e, and Cyfip1 were PCR‐amplified from mouse and/or human testis cDNA, and then cloned into pMIR‐REPORT vector, which lacks a 3′UTR (Ambion, Cat. no. AM5795).

Site‐directed mutagenesis

Site‐specific mutagenesis was performed, as previously described 87, to generate the mutant versions of the 3′UTR reporter vectors. The primers used to generate the mutants are provided in Appendix Table S4.

miRNA quantification

Total cellular RNA was isolated from cells and tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen). TaqMan‐qPCR was performed (in triplicate for each sample) using TaqMan® microRNA assays (Applied Biosystems).

Real‐time PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), as previously described 27. Reverse transcription–PCR analysis was performed by first generating cDNA from 1 μg of total cellular RNA using iSCRIPT (Bio‐Rad), followed by PCR amplification using SYBR Green and the ΔΔCt method (with ribosomal L19 for normalization).

Protein analysis

For Western blot analysis, cells were harvested in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, Cat. no. P8340) and phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF). Following incubation in lysis buffer on ice for 30 min, the samples were centrifuged at 16,050 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the lysates were transferred to new tubes, and protein level was quantified using the DC™ Protein Assay kit (Bio‐Rad, Cat. no. 500‐0112). Twenty micrograms of the protein samples was separated on an 8–12% polyacrylamide gel, and Western blot analysis was performed as previously described 41.

For anti‐puromycin detection of newly synthesized proteins, the image from gel electrophoresis was captured and the membrane was stained with Coomassie Blue to verify equal loading in all lanes. Densitometric measurements were performed by determining the density of each whole lane (incorporating the entire molecular weight range of puromycin‐labeled proteins) using ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Details of the antibodies used are provided in Appendix Table S5.

Protein synthesis was also measured using the L‐azidohomoalanine (AHA) Click‐iT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C10102) metabolic labeling reagents, following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cultured P19 cells were washed twice with warmed PBS and incubated in methionine‐free DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21013024) for 1 h. The medium was replaced with methionine‐free DMEM to which 50 μM of the methionine analog AHA was added. After incubation, the dishes were rinsed twice. Newly synthesized proteins labeled with Click‐iT AHA were conjugated with the tetramethylrhodamine alkyne (TAMRA) using the Click‐iT™ Tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) Protein Analysis Detection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C33370). Protein samples were separated on 10% SDS–PAGE and visualized using 532 nm excitation. The gel was subsequently stained with Coomassie blue for normalization.

Immunoprecipitation analysis

Testis from 1‐month‐old BL6 mice were harvested, decapsulated, and immediately put into 400 μl of ice‐cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA) supplemented with PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Phosphatase Arrest I, G‐Biosciences, Cat. no. 786‐450). The decapsulated testes were crushed with a pestle and incubated, with intermittent inversion, in the lysis buffer for 15 min on ice. NaCl was then added to all the samples at a final concentration of 150 mM, and the indicated samples were treated with 5 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml). The tubes were inverted and subjected to gentle vortex before 10 min of incubation on ice. The lysates were then spun at maximum speed for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used for IP analysis. Protein G sepharose beads (Invitrogen, Inc.) were prepared for IP analysis by washing them twice with NET‐2 buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton‐X 100). 40 μl of a 100 mg/ml bead slurry was incubated with 5 μl of either eIF4E polyclonal antibody or purified rabbit IgG (5 μg) resuspended in NET‐2 buffer supplemented with PMSF, protease inhibitor, and phosphatase arrest and incubated overnight at 4°C. The antibody‐coupled beads were washed three times with NET‐2 buffer with gentle centrifugation inbetween (250 g for 1 min). The washed antibody‐coupled beads were left on ice until the testis lysates were ready to be incubated. Testes lysates (400 μl), prepared as described above, were incubated for 2–4 h on ice. The beads were then washed eight times with NET‐2 buffer with gentle centrifugation inbetween. After the last wash, most of the supernatant was removed, 10 μl of SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) loading buffer was added, the beads were vortexed, boiled for 5 min, vortexed again, centrifuged at maximum speed (13,000 g), and the supernatant was loaded on a 12% polyacrylamide gel for Western blot analysis.

Control and Fragile‐X Syndrome neural progenitor and differentiated neuron preparation

Fibroblasts from a clinically healthy male control (GM08330) or a diagnosed Fragile‐X Syndrome male patient (GM05848) were purchased from Coriell Institute for Medical Research and used to derive induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) clones and subsequent stable, homogeneous neural progenitor cells (NPCs) as described 88. NPCs were expanded in 70% DMEM (Invitrogen), 30% Ham's F‐12 (Mediatech), supplemented with B‐27 (Invitrogen), 20 ng/ml EGF (Sigma), and 20 ng/ml bFGF (R&D Systems) on poly‐ornithine (Sigma)/laminin (Sigma)‐coated culture plates. Neural differentiation was induced by growth factor removal in the same media for 15 days before harvest. Cells were harvested by scraping and pelleting followed by total RNA (including miRNAs) isolation using a miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Biological triplicates were collected from each undifferentiated NPC and differentiated neuron cultures from control 8330‐8 and two clones from the FXS patient: 848‐1 and 848‐3 88.

NanoString nCounter miRNA profile analysis

miRNAs were processed with the NanoString nCounter system (NanoString, Seattle, Washington, USA) per vendor instructions with chipsets of Human miRNA v.1 (664 endogenous miRNAs and five housekeeping transcripts). Data archiving, normalization, analysis, and file export were performed using nSolver software v.2.5 (NanoString). Probe intensity data between samples were normalized using nSolver Software utilizing either the geometric means of five housekeeping genes (ACTB, B2M, GAPDH, RPL19, and RPLP0) or geometric mean normalization of the highest 100 values within each sample. For the purpose of comparison, control samples (n = 3 from each condition) were compared to combined FXS samples from both 848‐1 and 848‐3 (thus n = 6 from each condition).

Author contributions

MR and MFW conceived the project. MR, KT, T‐DMP, and MW designed experiments. MR, KT, T‐DMP, H‐WS, JND, SJ, and EYS performed experiments. SDS and SJH performed the NanoString nCounter miRNA Profile work. MR, KT, T‐DMP, H‐WS, JND, SJ, EYS, KJP, JG, HC‐A, and MFW analyzed the data. MR, KT, T‐DMP, and MFW wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Table EV2

Table EV3

Table EV4

Table EV5

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the HHS | NIH | National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) [R01 GM119128 to MW, T32 HD007203 to TDMP, F32 GM113487 to TDMP, and F30 HD089579 to JD], the Lalor Foundation (to KT), the UCSD Interfaces Scholar program (to SJ), NASA‐Ames (to KJP), the German Research Foundation [GR 1547 to JG], the FRAXA Research Foundation (to SJH), and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (to SJH).

EMBO Reports (2019) 20: e46566

References

- 1. Kutter C, Watt S, Stefflova K, Wilson MD, Goncalves A, Ponting CP, Odom DT, Marques AC (2012) Rapid turnover of long noncoding RNAs and the evolution of gene expression. PLoS Genet 8: e1002841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nasvall J, Sun L, Roth JR, Andersson DI (2012) Real‐time evolution of new genes by innovation, amplification, and divergence. Science 338: 384–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swanson WJ, Vacquier VD (2002) The rapid evolution of reproductive proteins. Nat Rev Genet 3: 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellegren H, Parsch J (2007) The evolution of sex‐biased genes and sex‐biased gene expression. Nat Rev Genet 8: 689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meiklejohn CD, Parsch J, Ranz JM, Hartl DL (2003) Rapid evolution of male‐biased gene expression in Drosophila . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9894–9899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Torgerson DG, Singh RS (2004) Rapid evolution through gene duplication and subfunctionalization of the testes‐specific alpha4 proteasome subunits in Drosophila . Genetics 168: 1421–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haerty W, Jagadeeshan S, Kulathinal RJ, Wong A, Ravi Ram K, Sirot LK, Levesque L, Artieri CG, Wolfner MF, Civetta A et al (2007) Evolution in the fast lane: rapidly evolving sex‐related genes in Drosophila . Genetics 177: 1321–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner LM, Chuong EB, Hoekstra HE (2008) Comparative analysis of testis protein evolution in rodents. Genetics 179: 2075–2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brawand D, Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Julien P, Csardi G, Harrigan P, Weier M, Liechti A, Aximu‐Petri A, Kircher M et al (2011) The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature 478: 343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang X, Zhang J (2004) Rapid evolution of mammalian X‐linked testis‐expressed homeobox genes. Genetics 167: 879–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stevenson BJ, Iseli C, Panji S, Zahn‐Zabal M, Hide W, Old LJ, Simpson AJ, Jongeneel CV (2007) Rapid evolution of cancer/testis genes on the X chromosome. BMC Genom 8: 129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh ND, Petrov DA (2007) Evolution of gene function on the X chromosome versus the autosomes. Genome Dyn 3: 101–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Llopart A (2012) The rapid evolution of X‐linked male‐biased gene expression and the large‐X effect in Drosophila yakuba, D. santomea, and their hybrids. Mol Biol Evol 29: 3873–3886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meisel RP, Malone JH, Clark AG (2012) Faster‐X evolution of gene expression in Drosophila . PLoS Genet 8: e1003013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W (2010) Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 79: 351–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R (2011) A parsimonious model for gene regulation by miRNAs. Science 331: 550–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ha M, Kim VN (2014) Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 509–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meunier J, Lemoine F, Soumillon M, Liechti A, Weier M, Guschanski K, Hu H, Khaitovich P, Kaessmann H (2013) Birth and expression evolution of mammalian microRNA genes. Genome Res 23: 34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vidigal JA, Ventura A (2015) The biological functions of miRNAs: lessons from in vivo studies. Trends Cell Biol 25: 137–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bracken CP, Scott HS, Goodall GJ (2016) A network‐biology perspective of microRNA function and dysfunction in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 17: 719–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenberg DS, Soreq H (2014) MicroRNA therapeutics in neurological disease. Curr Pharm Des 20: 6022–6027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khazaie Y, Nasr Esfahani MH (2014) MicroRNA and male infertility: a potential for diagnosis. Int J Fertil Steril 8: 113–118 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tanzer A, Stadler PF (2004) Molecular evolution of a microRNA cluster. J Mol Biol 339: 327–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reddy KB (2015) MicroRNA (miRNA) in cancer. Cancer Cell Int 15: 38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iwakawa HO, Tomari Y (2015) The functions of MicroRNAs: mRNA decay and translational repression. Trends Cell Biol 25: 651–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown V, Jin P, Ceman S, Darnell JC, O'Donnell WT, Tenenbaum SA, Jin X, Feng Y, Wilkinson KD, Keene JD et al (2001) Microarray identification of FMRP‐associated brain mRNAs and altered mRNA translational profiles in fragile X syndrome. Cell 107: 477–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maclean JA II, Chen MA, Wayne CM, Bruce SR, Rao M, Meistrich ML, Macleod C, Wilkinson MF (2005) Rhox: a new homeobox gene cluster. Cell 120: 369–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruno IG, Karam R, Huang L, Bhardwaj A, Lou CH, Shum EY, Song HW, Corbett MA, Gifford WD, Gecz J et al (2011) Identification of a microRNA that activates gene expression by repressing nonsense‐mediated RNA decay. Mol Cell 42: 500–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lou CH, Shao A, Shum EY, Espinoza JL, Huang L, Karam R, Wilkinson MF (2014) Posttranscriptional control of the stem cell and neurogenic programs by the nonsense‐mediated RNA decay pathway. Cell Rep 6: 748–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shum EY, Jones SH, Shao A, Dumdie J, Krause MD, Chan WK, Lou CH, Espinoza JL, Song HW, Phan MH et al (2016) The antagonistic gene paralogs Upf3a and Upf3b govern nonsense‐mediated RNA decay. Cell 165: 382–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang L, Shum EY, Jones SH, Lou CH, Dumdie J, Kim H, Roberts AJ, Jolly LA, Espinoza JL, Skarbrevik DM et al (2017) A Upf3b‐mutant mouse model with behavioral and neurogenesis defects. Mol Psychiatry 23: 1773–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Z, Zhang Y, Ku L, Wilkinson KD, Warren ST, Feng Y (2001) The fragile X mental retardation protein inhibits translation via interacting with mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 2276–2283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zalfa F, Giorgi M, Primerano B, Moro A, Di Penta A, Reis S, Oostra B, Bagni C (2003) The fragile X syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses. Cell 112: 317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stefani G, Fraser CE, Darnell JC, Darnell RB (2004) Fragile X mental retardation protein is associated with translating polyribosomes in neuronal cells. J Neurosci 24: 7272–7276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Betel D, Koppal A, Agius P, Sander C, Leslie C (2010) Comprehensive modeling of microRNA targets predicts functional non‐conserved and non‐canonical sites. Genome Biol 11: R90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Gendt K, Verhoeven G, Amieux PS, Wilkinson MF (2014) Genome‐wide identification of AR‐regulated genes translated in Sertoli cells in vivo using the RiboTag approach. Mol Endocrinol 28: 575–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van der Heyden MA, Defize LH (2003) Twenty one years of P19 cells: what an embryonal carcinoma cell line taught us about cardiomyocyte differentiation. Cardiovasc Res 58: 292–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bartel DP (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E (2011) Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet 12: 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McGuinness MP, Linder CC, Morales CR, Heckert LL, Pikus J, Griswold MD (1994) Relationship of a mouse Sertoli cell line (MSC‐1) to normal Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod 51: 116–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hu Z, Dandekar D, O'Shaughnessy PJ, De Gendt K, Verhoeven G, Wilkinson MF (2010) Androgen‐induced Rhox homeobox genes modulate the expression of AR‐regulated genes. Mol Endocrinol 24: 60–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Steinberger A, Jakubowiak A (1993) Sertoli cell culture: historical perspective and review of methods In The Sertoli cell, Russell L, Griswold M. (eds), pp 155–180. Clearwater, FL: Cache River Press; [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sutton KA, Maiti S, Tribley WA, Lindsey JS, Meistrich ML, Bucana CD, Sanborn BM, Joseph DR, Griswold MD, Cornwall GA et al (1998) Androgen regulation of the Pem homeodomain gene in mice and rat Sertoli and epididymal cells. J Androl 19: 21–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Russell LD, Steinberger A (1989) Sertoli cells in culture: views from the perspectives of an in vivoist and an in vitroist. Biol Reprod 41: 571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dallaire A, Frederick PM, Simard MJ (2018) Somatic and germline MicroRNAs form distinct silencing complexes to regulate their target mRNAs differently. Dev Cell 47: 239–247.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kanatsu‐Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T (2003) Long‐term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod 69: 612–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maezawa S, Hasegawa K, Yukawa M, Sakashita A, Alavattam KG, Andreassen PR, Vidal M, Koseki H, Barski A, Namekawa SH (2017) Polycomb directs timely activation of germline genes in spermatogenesis. Genes Dev 31: 1693–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Song R, Ro S, Michaels JD, Park C, McCarrey JR, Yan W (2009) Many X‐linked microRNAs escape meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. Nat Genet 41: 488–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]