Abstract

Objective

To evaluate adherence as well as patient preference and satisfaction of once-yearly intravenous zoledronic acid versus other bisphosphonates treatments.

Methods

In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, a systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library and EMBASE databases, over the date range of 2000–2016. Following the PICO (Population, Interventions, Comparator, Outcomes) elements, eligibility criteria included: (1) participants: adults over 18 with osteoporosis and adults who were at high risk of developing low bone density as a result of chronic use of glucocorticoids; (2) intervention: adherence or patient preference/satisfaction of once-yearly zoledronic acid treatment; (3) comparator: other bisphosphonates; (4) outcome: data about adherence, persistence, compliance, preference and satisfaction criteria. Specific exclusion criteria were also applied.

Results

Adherence to zoledronate is only quantified in one study showing that mean proportion of days covered for zoledronic acid was greater than for ibandronate users. Three studies showed 100% of compliance to zoledronate treatment and only one study showed zoledronic acid provided the highest persistence rates. Once-yearly intravenous infusion of zoledronic acid was clearly preferred. Only one article indicated preference for schedules that were once monthly or less frequent and other preference results practically equal between once-yearly intravenous infusion or weekly oral. Although there is little evidence, adherence to osteoporosis treatment is improved with annual intravenous zoledronate regimen. Moreover, patients appear to have preference for less frequent dosing. Switching from oral to intravenous therapy, based on the opportunities offered by an integrated health management area, may allow obtaining better outcomes in adherence to osteoporosis treatment.

Keywords: adherence, preference, satisfaction, osteoporosis, zoledronic acid

Introduction

Adherence is an important issue which is directly linked with the management of chronic diseases. It has been established that the medication non-adherence lowers the treatment effectiveness and raises medication cost.1 Non-adherence is a priority public health issue due to its negative consequences such as therapeutic failures, higher rates of hospitalisation and increased healthcare costs.2 Indeed, low adherence with prescribed treatments is very common.3

According to WHO, medications adherence has been defined as the extent to which a person’s behaviour—taking medication, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider.4 On the other hand, the terms adherence and compliance are often interchanged, although compliance is associated with a passive act without patient involvement. In recent years, the concept of qualitative adherence has been developed including the theoretical intakes and the quality of the same (time administration, frequency of dosage or food restrictions.5 While achieving adequate adherence is important, continuation of the treatment for the prescribed duration, persistence, is equally essential to the success of a medical regimen. Thus, adherence incorporates compliance and persistence with medication intake and describes the extent and the quality of this.6 7

Many studies have been published on the topic of adherence to bisphosphonate medications, which considered poor adherence as a major limiting factor in clinical practice.8 9 Although daily oral dosing is effective, long-term adherence with oral medications for osteoporosis is low—a phenomenon also observed with other chronic asymptomatic disorders.5

It is necessary to improve overall adherence for bisphosphonate treatment in order to reach maximum treatment effects. Several strategies and interventions have been attempted with very modest results.10 11 Extended dosing intervals may be a beneficial strategy to improve treatment adherence. Intravenous zoledronic acid 5 mg once yearly is a convenient and effective treatment option that may have an advantage over other agents in which adherence to treatment regimens is a recognised problem.12 This bisphosphonate is recommended as a first-line agent for osteoporosis treatment by international guidelines.13 14 This regimen has demonstrated to be effective and safe in osteoporosis treatment.15

On the other hand, patient preference and satisfaction are important determinants of adherence to therapies for chronic conditions, including osteoporosis.16 17 It is important to consider patient preference individually when prescribing treatment for osteoporosis to ensure that long-term disease management is effective. Furthermore, a good patient expectations with the regimen of treatment could also determine a higher degree of satisfaction,18 19 which also will result in greater adherence.

There are very few and inconclusive studies evaluating adherence and preference to an annual regimen of bisphosphonate. The purpose of this article is to review the current literature surrounding adherence and patient preference of once-yearly intravenous zoledronate compared with other bisphosphonate options.

Methods

Search strategy and studies selection

A literature search was performed using MeSH terms and keywords in PubMed, Cochrane Library and EMBASE databases between January 2000 and December 2016. Search strategy is described in the box. The outcomes of adherence to therapy and patient preference are evaluated separately; therefore, for the purpose of this review, the studies will be also discussed separately. Moreover, additional articles have been identified by citation tracing, which was carried out at a later date.

Box. Full search strategy used in the search in databases.

MedLine and CochraneLibrary

First search

#1. ((adherence) OR persistence) OR compliance

#2. (bisphosphonate) AND zoledronic) AND osteoporosis

#3. (((((adherence, medication[MeSH Terms)) OR adherence, patient(MeSH Terms)) OR medication persistence[MeSH Terms]) OR persistence, medication(MeSH Terms)) OR compliance, medication(MeSH Terms)) OR compliance, patient(MeSH Terms)

#4. (bisphosphonates(MeSH Terms)) AND zoledronic) AND osteoporosis(MeSH Terms)

#5. #1 AND #2

#6. #3 AND #4

#7. #5 OR #6

#8. limit 10 from Jan 2000 to Dec 2016

Second Search

#1. ((preference) OR satisfaction)

#2. (bisphosphonate) AND zoledronic) AND osteoporosis

#3. ((((patient preference[MeSH Terms]) OR preference, patient[MeSH Terms] OR satisfaction(MeSH Terms]) OR patient satisfaction[MeSH Terms)) OR satisfaction, patient[MeSH Terms])

#4.(bisphosphonates[MeSH Terms]) AND zoledronic) AND osteoporosis(MeSH Terms)

#5.#1 AND #2

#6. #3 AND #4

#7. #5 OR #6

#8. limit 10 from Jan 2000 to Dec 2016

EMBASE

First search

#1. ’adherence'/exp OR ’adherence' OR ’persistence'/exp OR ’persistence' OR ’compliance'/exp OR ’compliance' AND (2000-2016)/py

#2. ’bisphosphonate'/exp OR ’bisphosphonate' AND ’zoledronic' AND (’osteoporosis'/exp OR ’osteoporosis'

#3. #1 AND #2

Second Search

#1. ’preference'/exp OR ’preference' OR ’satisfaction'/exp OR ’satisfaction' OR AND (2000-2016)/py

#2. ’bisphosphonate'/exp OR ’bisphosphonate' AND ’zoledronic' AND (’osteoporosis'/exp OR ’osteoporosis'

#3. #1 AND #2

Article selection and identification in the databases were independently and systematically performed by authors, who carried out initial identification through the title and the abstract. Then, relevance and eligibility criteria were reviewed. Then, a list of potentially relevant full text articles was created and was reviewed for relevance. They were essential to meet provisional, intentionally overly inclusive, eligibility criteria to reduce the risk of inappropriate exclusions by a single reviewer.20 Discrepancies were solved through consensus among authors.

Study eligibility criteria

To identify studies for this review, searches were developed according to the PICO (Population, Interventions, Comparator, Outcomes) principle21: (P) Populations: studies were limited to those recruiting the following individuals: adults over 18 with osteoporosis (not Paget’s disease, cancer or any other disease of bone metabolism) and adults who were at high risk of developing low bone density as a result of chronic use of glucocorticoids (GC) or a condition associated with the chronic use of GC; (I) Intervention: studies were included if they either evaluated adherence or patient preference/satisfaction of once-yearly zoledronic acid treatment (C) Comparator: studies were included if adherence, persistence or compliance as well as preference or satisfaction about zoledronate treatment were compared with other bisphosphonates (O) Outcomes: Data about adherence, persistence, compliance, preference and satisfaction criteria evaluation and analysis were identified.

Studies in languages other than Spanish or English or those whose full text could not be found were excluded.

Results

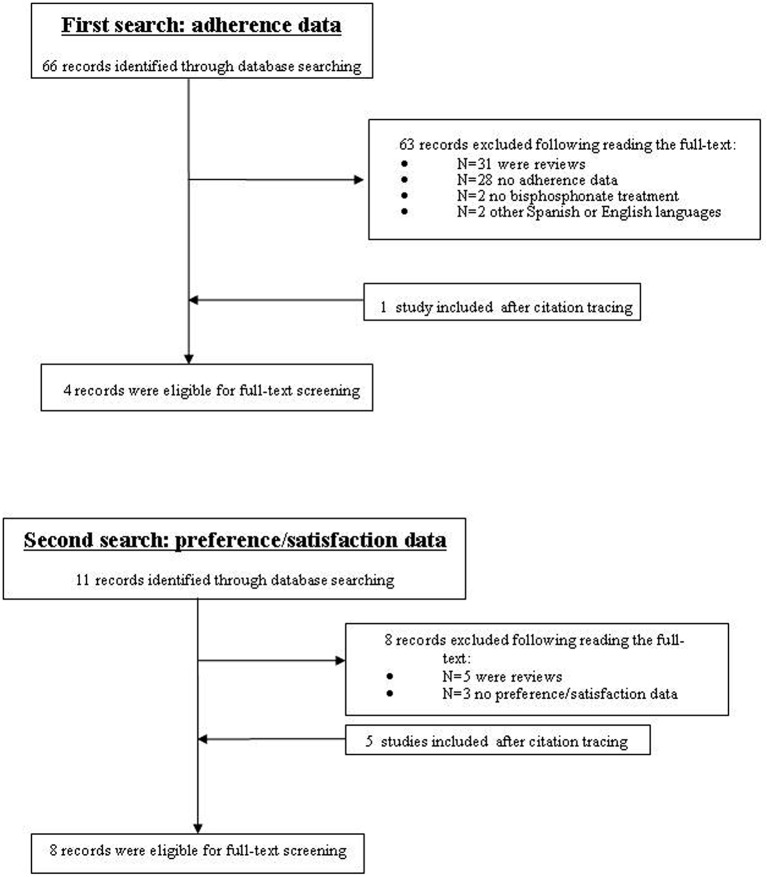

The first search identified 66 studies, of which 31 articles were reviews (figure 1). After reviewing, studies with no adherence data (n=28), studies with no bisphosphonates treatment (n=2) and those in other languages (n=2) were excluded. Thus, three articles were only included in our review,22–24 and one article was added after citation tracing.25

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1 contains details of these included articles. All of them are observational studies. Overall adherence was assessed by Curtis et al,22 who demonstrated that the mean proportion of days covered (PDC) was significantly greater for once-yearly intravenous zoledronic acid (82%, p<0.0001) compared with quarterly intravenous ibandronate (approximately 60%). Approximately 30% of zoledronate users did not receive a second infusion. The other three studies23–25 evaluated the compliance, measured indirectly by means the medication possession ratio (MPR). Adherence, defined as PDC, is similar to a MPR.26 However, as adherence incorporates compliance and persistence data, which can be explained by means different MPR definitions, these are interpreted in table 1. These studies showed the same results, 100% of compliance to zoledronic acid. Finally, persistence was studied only by Ziller et al.25 They observed that in spite of suboptimal persistence with all treatments, zoledronate administration provided the highest persistence rates (65.6%, p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Adherence data among once-yearly intravenous zoledronate and shorter interval bisphosphonates

| Reference | Study design | Duration | Population | Osteoporosis treatment | Methodology | Results |

| Eliasaf et al 24 | Observational prospective study | 6-month period | Postmenopausal women (n=86) | Oral BPS (n=39) Intravenous ZOL annually (n=12) Other therapies (n=35) |

Compliance: MPR, number of doses dispensed in relation to those prescribed over a period and reported as a percentage | 100%±0 (ZOL) p<0.0001 83.5%±28.3 (BPS) |

| Persistence, continuation of treatment without a >30-day gap in prescription refills | 77% (BPS) No data (ZOL) |

|||||

| Chávez-Valencia et al 23 | Observational prospective study | 12-month period | Postmenopausal women (n=104) | Oral ALE weekly (n=52) Intravenous ZOL annually (n=52) +calcium and vit D |

Compliance: MPR, defined by the ratio of supplied-to-required pills in 1 year. (Pill counts and exchange of empty boxes) | Group ALE: 66% for both medications Group ZOL: 100% for ZOL 86% calcium and vit D |

| Ziller et al 25 | Observational retrospective cohort study | 24-month period | Patients with at least one prescription of BP (n=261 289) | Oral: IBA monthly (n=14 426) ALE daily/weekly (n=173 662) ETD daily (n=1002) RIS (daily/weekly) (n=46 542) Intravenous: ZOL annually (n=13 132) IBA quarterly (n=12 525) |

Compliance: MPR, total number of treatment days covered within the 1 year period after index prescription date | 100% (ZOL) p<0.0001 70% (IBA quarterly), 62% (IBA monthly), 57% (ALE weekly), 59% (ETD daily), 58% (RIS daily), 53% (ALE daily), 53% (RIS weekly), 47% (RIS daily), 33% (ALE daily) |

| Persistence, the proportion of patients who remained on their initially prescribed therapy at 1 year | 65.6% (ZOL) p<0.0001 56.6% (IBA, quarterly), 51% (IBA monthly), 44.8% (ALE weekly), 43.4% (ETD daily), 42.3% (RIS daily), 37.8% (ALE daily), 35.2% (RIS weekly), 30.6% (RIS daily), 17.3% (ALE daily) |

|||||

| Curtis et al 22 | Observational prospective study | 18-month period | Individuals receiving IBA or ZOL for osteoporosis | Intravenous ZOL annually (n=775) Intravenous IBA quarterly (n=846) |

Adherence: quantified by the PDC, measured continuously and dichotomously (>=80%) | Group ZOL: 82%, p<0.0001 Group IBA: 58%–62%, depending on time period |

ALE, alendronate; BPS, bisphosphonates; ETD, etidronate; IBA, ibandronate; MPR, medication possession ratio; PDC, proportion of days covered. It is expressed as a proportion, computed by summing the number of days the patient is exposed to the medication, beginning with the first infusion and extending to the end of follow-up and dividing by the amount of follow-up time; RIS, risedronate; ZOL, zoledronate.

The second search for preference/satisfaction identified 11 studies (figure 1). All of them evaluated it by means of different questionnaires. Among them, five review articles and three studies with no satisfaction or preference data on zoledronic acid were excluded. Then, three studies were selected27–29 and five more were included by cross-reference.22 30–33 Table 2 shows the results obtained.

Table 2.

Preference and satisfaction data

| Reference | Study design | Duration | Population | Osteoporosis treatments | Methodology | Results |

| Eliasaf et al 24 | Observational prospective study | 6-month period | Postmenopausal women (n=86) | Oral BPS (n=39) Intravenous ZOL annually (n=12) Other therapies (n=35) |

Question about their preferences regarding the frequency of the dosing regimen | •57% preferred annual treatment •22% preferred monthly treatment over other possibilities such as daily, weekly or every 6 months •5% preferred to receive treatment every 6 months |

| Hadji et al 29 | Randomised controlled trial | 12-month period | Postmenopausal women (n=604) (408 ZOL) (196 ALE) |

Intravenous ZOL annually (n=408) Oral ALE weekly (n=196) |

(1)Remain on same therapy or change?: Remain/change/missing (2) Easy to manage medication: Not at all/somewhat/very/extremely/missing (3) Medication fits with lifestyle: Not at all/somewhat/very/extremely/missing (4) Convenient to take medication: Not at all/somewhat/very/extremely/missing (5) Willing to continue to use medication: Not at all/somewhat/very/extremely/missing (6) Most important reason for preference: Too medicines/not effective/experienced side effects/intake too inconvenient/did not like infusion/forgot to take it/did not like taking pills regularly/other |

ZOL group: •80.9% preferred to continue with intravenous treatment. ALE group: •48.7% preferred to continue with oral administration. •42.9% (82/191) preferred to switch to the alternative treatment of a once-yearly infusion |

| Orwoll et al 32 | Randomised controlled trial | 12-month period | Men with osteoporosis (n=302) |

Intravenous ZOL annually+oral placebo weekly (n=154) Oral ALE weekly+intravenous placebo annually (n=148) |

Which regimen was: (1) More convenient (2) More satisfying (3) More appealing to be taken for a longer period (4) Preferred |

•74.2% preferred once-yearly intravenous infusion. •15.3% preferred weekly oral ALE. •10.5% had no preference |

| Ryzner et al 33 | Prospective telephone survey | 24-month period | Osteoporosis clinic staffed by a rheumatologist and clinical pharmacists | None (n=56) Weekly oral (n=28) Monthly oral (n=2) Injection every 3 months (n=4) Yearly injection (n=0)* |

Set of questions to determinate the route and frequency of BPS administration that the patients: (1) Prefer (2) Is most convenient (3) Is easiest to remember |

•24.4% preferred once-monthly or once-yearly regimens •53.3% indicated preference for schedules that were once-monthly or less frequent •33.3% indicated that once-yearly infusion was the most convenient |

| Reid et al 31 | Randomised controlled trial | 12-month period | Patients with ZOL or RIS for prevention and treatment of GIO (n=833) |

Intravenous ZOL annually+oral placebo daily (n=416) Oral RIS daily+a single infusion of intravenous placebo (n=417) |

Not specified | •81% preferred the intravenous preparation and 9% the oral preparation for convenience •78% preferred the intravenous preparation and 8% the oral preparation for satisfaction •84% were willing to take the intravenous preparation long term and 9% the oral preparation |

| McClung et al 27 | Randomised controlled trial | 12-month period | Postmenopausal women who were receiving oral ALE for at least 1 year immediately prior to randomisation (n=225) |

Intravenous ZOL+oral placebo weekly (n=113) Oral ALE weekly+a single infusion of intravenous placebo (n=112) |

Which treatment regimen they thought: (1) Was more convenient (2) Better fit their lifestyle (3) They would be more willing to take for a long period of time (multiple years) (4) They preferred. |

•78.7% preferred once-yearly intravenous infusion •9% preferred once-a-week capsules •11.8% considered equal both treatments |

| Saag et al 28 | Randomised controlled trial | 24-month period | Postmenopausal women (n=128) |

Intravenous ZOL+oral placebo weekly (n=69) Oral ALE weekly+a single infusion of intravenous placebo (n=59) |

Which treatment: (1) They considered more convenient (2) They considered more satisfying (3) They would be willing to take for a long period of time (4) They preferred |

•66.4% preferred once-yearly intravenous infusion •19.7% preferred weekly oral ALE •13.9% had no preference |

| Fraenkel et al 30 | Observational Prospective study | Non-described | Postmenopausal women and men (n=212) |

Oral BPS weekly Intravenous BPS quarterly Intravenous BPS yearly |

After of an educational session participants completed an ACA questionnaire to determine their treatment preferences for: (1) Oral BPS taken once per week (2) Intravenous BPS given every 3 months (3) Intravenous BPS given once per year |

•44.3% preferred once-yearly intravenous infusion •40.1% preferred weekly oral •2.8% preferred quarterly intravenous infusion •10.4% undecided |

*Yearly injectable bisphosphonate therapy had not yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration at the time of study initiation.

ACA, adaptive conjoint analysis; ALE, alendronate; BPS, bisphosphonates; GIO, glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis; RIS, risedronate; ZOL, zoledronic acid.

All studies were randomised control trials except those by Ryzner et al 33 and Fraenkel et al,30 which are observational prospective. All of them shown that the participants clearly preferred once-yearly intravenous infusion of zoledronic acid 5 mg. Only the study by Ryzner et al 33 indicated preference for schedules that were once monthly or less frequent and Fraenkel et al 30 showed practically equal results between preference by once-yearly intravenous infusion (44.3%) or by weekly oral (40.1%).

Discussion

This is the first review that summarises the available data about adherence to and preference of once-yearly zoledronic acid treatment. The review highlights the insufficient evidence available to comparing newer osteoporosis therapies.

Adherence is an important variable of outcome that is determined by compliance and persistence of medication intake and describes the extent and the quality of this.6 7 Despite little evidence, the results obtained mainly highlight the high potential of annual osteoporosis regimen for improving patient adherence.

Some authors point that although the adherence may be improved with less frequent osteoporosis medication dosing, there are factors that influence adherence to annual zoledronic treatment.34 35 Other authors explain that adherence is affected by age, the fear of rare side-effects such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fractures, not feeling that treatment is working and not believing that they have a disease that needs to be treated.25 36 37

Moreover, the challenge with less frequent dosing of antiosteoporosis medications may be the need for healthcare professionals to take more direct control of parenteral treatment delivery, the need for automated reminders for follow-up, with the direct and indirect costs of delivery and resource implications to achieve optimal outcomes.38 The study by Curtis et al 22 describes that one factor associated with adherence to intravenous annual infusion is receipt of the first infusion in an outpatient hospital-based infusion centre rather a physician’s office. As a practical matter, a key element of promoting adherence on an infrequent dose intravenous therapy requires ensuring that the patient is scheduled to repeat the infusion and remembers to return. Therefore, verifying the reliability of the processes of care to schedule the next infusion and remind patients at the time it is needed is likely to be an important factor in ensuring high adherence with intravenous zoledronic acid treatment.

On the other hand, this review highlights that the results about preference of treatment are more conclusive. All randomised controlled trials pointed that a single annual injection is preferred with respect to other regimens of treatment. These results are consistent with previous studies with oral bisphosphonates preference, which have shown that patients prefer reduced dosing frequency.39 40 Although two studies did not show good data with respect to preference to annual infusion of zoledronate treatment, this can be explained because these studies were surveys to the population which were with different regimen treatments with bisphosphonate but had no randomisation of two different treatments (an annual intravenous injection or daily/weekly oral) as take place in the other studies.

Among them, the main reasons patients receiving zoledronic acid would prefer to continue a once-yearly infusion were to avoid the requirement to take pills regularly, side effects and having too many medicines overall.40

Limitations. This review has some limitations. The main limitation is that there are not enough studies comparing zoledronic acid with other parenteral or oral bisphosphonates with regard to patient therapy adherence. Zoledronic acid infusions ensure 1-year adherence, but further works should address the assumption that longer dosing intervals translate into better adherence in subsequent years.41 Moreover, calculating MPR for products with less frequent regimens can be misleading. Due to the nature of administration, each application leads to 100% compliance within the specified time frame (eg, 1 year in the case of zoledronate 5 mg). Therefore, the differences in compliance are a simple consequence of changing the time of application or persistence.25 Since zoledronic acid treatment is yearly administered, this regimen ensures that adherence in the first year is 100%. Therefore, to assess compliance with these drugs, longer follow-up is needed.

Conclusion

Based on currently available data, there is a possibility for benefit of using once-yearly zoledronic acid to improve adherence. Moreover, patients appear to have a preference for less frequent dosing if agents are perceived to be of equivalent benefit as this is less disruptive to their lifestyle. In this way, since there may be a benefit for adherence and overall patients tend to prefer extended dosing intervals, a discussion between the patient and prescriber should take place to decide on what is best for each patient and it should be reassessed on a regular basis to see if changes are warranted. Anyway, due to the low number of articles included in this review, it needs to emphasise that while it appears that less frequent dosing of bisphosphonates assists with adherence and preference, further studies are needed in order to obtain more conclusive data.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Bernardo Santos Ramos.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McElnay JC, McCallion CR, al-Deagi F, et al. . Self-reported medication non-compliance in the elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1997;53:171–8. 10.1007/s002280050358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Larrea P V, Mir M I. Adherencia al tratamiento en el paciente anciano. Inf Ter Sist Nac Salud 2004;28:113–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3. McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:2868–70. 10.1001/jama.288.22.2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization 2003;194. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medications. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2005;353:487–97. 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Badamgarav E, Fitzpatrick LA. A new look at osteoporosis outcomes: the influence of treatment, compliance, persistence, and adherence. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:1009–12. 10.4065/81.8.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Payer J, Killinger Z, Sulková I, et al. . Therapeutic adherence to bisphosphonates. Biomed Pharmacother 2007;61:191–3. 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lenart BA, Lorich DG, Lane JM. Atypical fractures of the femoral diaphysis in postmenopausal women taking alendronate. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1304–6. 10.1056/NEJMc0707493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kwek EB, Goh SK, Koh JS, et al. . An emerging pattern of subtrochanteric stress fractures: a long-term complication of alendronate therapy? Injury 2008;39:224–31. 10.1016/j.injury.2007.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. . Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;16:CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gleeson T, Iversen MD, Avorn J, et al. . Interventions to improve adherence and persistence with osteoporosis medications: a systematic literature review. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:2127–34. 10.1007/s00198-009-0976-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deeks ED, Perry CM. Zoledronic acid: a review of its use in the treatment of osteoporosis. Drugs Aging 2008;25:963–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al. . American association of clinical endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract 2010;16(Suppl 3):1–37. 10.4158/EP.16.S3.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. . European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:23–57. 10.1007/s00198-012-2074-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Black DM, Reid IR, Cauley JA, et al. . The Effect of 6 versus 9 Years of Zoledronic Acid Treatment in Osteoporosis: A Randomized Second Extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2015;30:934–44. 10.1002/jbmr.2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reginster JY, Rabenda V, Neuprez A. Adherence, patient preference and dosing frequency: understanding the relationship. Bone 2006;38:S2–S6. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.01.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gold DT, Horne R, Coon CD, et al. . Development, reliability, and validity of a new Preference and Satisfaction Questionnaire. Value Health 2011;14:1109–16. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kravitz RL. Patients' expectations for medical care: an expanded formulation based on review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 1996;53:3–27. 10.1177/107755879605300101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weaver M, Patrick DL, Markson LE, et al. . Issues in the measurement of satisfaction with treatment. Am J Manag Care 1997;3:579–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, et al. . Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006544 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boudin F, Nie JY, Bartlett JC, et al. . Combining classifiers for robust PICO element detection. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:29 10.1186/1472-6947-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Curtis JR, Yun H, Matthews R, et al. . Adherence with Intravenous Zoledronate and IV Ibandronate in the U.S. Arthritis Care Res 2012;6:1054–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chávez-Valencia V, Arce-Salinas CA, Espinosa-Ortega F. Cost-minimization study comparing annual infusion of zoledronic acid or weekly oral alendronate in women with low bone mineral density. J Clin Densitom 2014;17:484–9. 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eliasaf A, Amitai A, Maram Edry M, et al. . Compliance, persistence, and preferences regarding osteoporosis Treatment during active therapy or drug holiday. J Clin Pharmacol 2016;56:1416–22. 10.1002/jcph.738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ziller V, Kostev K, Kyvernitakis I, et al. . Persistence and compliance of medications used in the treatment of osteoporosis--analysis using a large scale, representative, longitudinal German database. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;50:315–22. 10.5414/CP201632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. . Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44–7. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McClung M, Recker R, Miller P, et al. . Intravenous zoledronic acid 5 mg in the treatment of postmenopausal women with low bone density previously treated with alendronate. Bone 2007;41:122–8. 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saag K, Lindsay R, Kriegman A, et al. . A single zoledronic acid infusion reduces bone resorption markers more rapidly than weekly oral alendronate in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. Bone 2007;40:1238–43. 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hadji P, Ziller V, Gamerdinger D, et al. . Quality of life and health status with zoledronic acid and generic alendronate--a secondary analysis of the Rapid Onset and Sustained Efficacy (ROSE) study in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:2043–51. 10.1007/s00198-011-1834-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink D. Patient treatment preferences for osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:729–35. 10.1002/art.22229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reid DM, Devogelaer JP, Saag K, et al. . Zoledronic acid and risedronate in the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (HORIZON): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1253–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60250-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Orwoll ES, Miller PD, Adachi JD, et al. . Efficacy and safety of a once-yearly i.v. Infusion of zoledronic acid 5 mg versus a once-weekly 70-mg oral alendronate in the treatment of male osteoporosis: A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, active-controlled study. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:2239–50. 10.1002/jbmr.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryzner KL, Burkiewicz JS, Griffin BL, et al. . Survey of bisphosphonate regimen preferences in an urban community health center. Consult Pharm 2010;25:671–5. 10.4140/TCP.n.2010.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cramer JA, Lynch NO, Gaudin AF, et al. . The effect of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal women: a comparison of studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Clin Ther 2006;28:1686–94. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ. Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 2006;38:922–8. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diab DL, Watts NB. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2013;20:501–9. 10.1097/01.med.0000436194.10599.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reginster JY, Rabenda V. Patient preference in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis with bisphosphonates. Clin Interv Aging 2006;1:415–23. 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.4.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee S, Glendenning P, Inderjeeth CA. Efficacy, side effects and route of administration are more important than frequency of dosing of anti-osteoporosis treatments in determining patient adherence: a critical review of published articles from 1970 to 2009. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:741–53. 10.1007/s00198-010-1335-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Emkey R, Koltun W, Beusterien K, et al. . Patient preference for once-monthly ibandronate versus once-weekly alendronate in a randomized, open-label, cross-over trial: the Boniva Alendronate Trial in Osteoporosis (BALTO). Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1895–903. 10.1185/030079905X74862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hadji P, Minne H, Pfeifer M, et al. . Treatment preference for monthly oral ibandronate and weekly oral alendronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: A randomized, crossover study (BALTO II). Joint Bone Spine 2008;75:303–10. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tadrous M, Wong L, Mamdani MM, et al. . Comparative gastrointestinal safety of bisphosphonates in primary osteoporosis: a network meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1225–35. 10.1007/s00198-013-2576-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]