Abstract

American Indian (AI) adolescents living on reservations report much higher substance use rates compared to other youth yet there are few effective prevention interventions developed for them. This paper presents findings from formative research undertaken to guide adaptation for AI youth of a prevention intervention, Be Under Your Own Influence (BUYOI), previously found to be effective in reducing substance use among middle-school youth. We conducted focus groups with 7th graders, the primary target audience, and photovoice with 11th graders, the role models who would help deliver the campaign, to inform surface and deep structure adaptation. Both age groups noted the pervasiveness of substance use on the reservation and indicated that this posed a major challenge to being drug and alcohol free. Students also described aspects of their community that tied to signs of social disorganization. However, these youth have much in common with other youth, including high future aspirations, involvement in activities and hobbies, and influence from family and friends. At the same time, there were important differences in the experiences, environment, and values of these AI youth, including emphasis on different types of activities, a more collectivist cultural orientation, tribal identity and pride, and the importance of extended families.

Keywords: substance use, prevention, American Indian, media campaign, cultural adaptation, peer mentoring

American Indian (AI) adolescents living on reservations consistently report higher rates of substance use compared to other similarly-aged youth (Swaim & Stanley, 2018). They also initiate use earlier (Stanley & Swaim, 2015), placing them at heightened risk for developing substance use disorders (Dawson, Goldstein, Chou, Ruan, & Grant, 2008) and other substance-related problems (Griffin, Bang, & Botvin, 2010). Despite this, few prevention interventions for AI youth have been developed (Jumper-Reeves, Dustman, Harthun, Kulis, & Brown, 2014).

This paper presents findings from formative research used to adapt, for AI youth, a prevention intervention, Be Under Your Own Influence (BUYOI), that was previously found to be effective in reducing marijuana and alcohol use among middle-school youth in a cluster randomized trial (Slater et al., 2006). Formative research was the first step of a subsequent cluster randomized trial (Swaim, 2017) to test the effectiveness of the adapted intervention in reducing substance use among AI 7th graders attending schools on three reservations (two Northern Plains [NP] and one Southwest [SW]) compared to counterparts on three control reservations. The results presented here contribute to a better understanding of this unique underserved and understudied population, and potentially encourage increased attention to the distinctive issues facing them.

Media-based communications campaigns can be effective in altering substance use behaviors when carefully targeted with proven methodologies and approaches (Anker, Feeley, McCracken, & Lagoe, 2016; Wakefield, Loken, & Hornik, 2010). BUYOI is a media-based substance use prevention campaign developed through extensive formative research and evaluation across diverse adolescent populations (Kelly, Comello, & Slater, 2006). Although behavior change theories such as Theory of Reasoned Action contributed to its development, it broadly relies on Re-framing Theory (Slater, 2006), where campaign messages seek to reinterpret a behavior in terms consistent with personal and/or social identity. BUYOI messages, targeted to middle-school youth, reframe substance use to be inconsistent with personal autonomy and aspirations. It also capitalizes on the prosocial influence of older peers in a key time for middle-school students when they begin making decisions about future goals and substance use (Karcher, 2005).

Cultural Adaptation

Although the campaign has undergone significant testing (Slater, Kelly, Lawrence, Stanley, & Comello, 2011), the targeted youth were not AI nor did they live on reservations. Thus, we sought to adapt the campaign to ensure that its themes, images, messaging, and delivery modes would resonate and reflect the experiences of AI youth. Research has consistently demonstrated that culturally-appropriate health interventions are more effective than “usual care or other control conditions” (Barrera, Castro, Stryker, & Toobert, 2013, p. 202). Cultural adaptation has been defined as “the systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment (EBT) or intervention protocol to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meanings, and values” (Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey, & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009, p.362). Cultural adaptations have been categorized into two broad groups (Resnicow, Baranowski, Ahluwalia, & Braithwaite, 1999; Wilson & Miller, 2003). Surface structure features (or presentation strategies) match intervention materials and messages to observable, superficial characteristics of a target population and serve to increase the receptivity of messages. Deep structure features (or content strategies) increase the salience of messages due to integration of cultural values and other elements into intervention activities and messages. Our formative research was designed to consider both adaptation types to maximize potential for effectiveness and, if effective, to increase adoption by and sustainability within schools.

Cultural Congruence of BUYOI

Before proceeding with adaptation, members of the research team presented the original campaign to staff at several reservation schools and found widespread support for its themes – personal autonomy and aspirations - and content. We then discussed the campaign and its components with each of three community advisory committees (CAC), one from each treatment community. The CACs were comprised of 6–8 community members and school staff who provided input on campaign development and implementation; during the formative research period, we met twice with each CAC. Each CAC expressed enthusiastic support for the campaign while noting that some campaign wording and images were not relevant or culturally congruent (e.g., skiing, rock climbing), indicating a need for surface adaptation. Since younger students often look up to older students, the CAC’s felt strongly that local high school youth should play a prominent role in the images and delivery of campaign messages. By showing that there are local, recognizable high school students making good choices, the CACs believed the campaign would be more impactful with the middle-school youth. This represents a deep structure adaptation as the original BUYOI relied on visual and message uniformity across schools (with only one poster in year two of the campaign including local youth). Each CAC also identified channels for message delivery (e.g., local radio stations and media) and community resources for producing media if needed.

We next conducted two qualitative studies --- focus groups with 7th graders, the intervention’s target audience, (Study 1) and photovoice with selected high school campaign role models (Study 2). Focus groups are an excellent method for obtaining adolescent perspectives on issues of health and wellness and assisting in adaptation of effective health interventions (Peterson-Sweeney, 2005; Vangeepuram, Carmona, Arniella, Horowitz, & Burnet, 2015). They are particularly useful for learning about group norms and processes and obtaining feedback about previous findings (Gill, Stewart, Treasure, & Chadwick, 2008). Photovoice was chosen for the older students because it engages them in the prevention process and acknowledges the importance of their experiences in designing and implementing interventions (Brazg, Bekemeier, Spigner, & Huebner, 2011; Wang, 2006). Photovoice is also useful in cultures like that of American Indian that rely on storytelling, narrative, and images to convey experiences of community life (Castleden, Garvin, & First Nation, 2008).

All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board (IRB) and tribal IRBs and/or councils. Parental consent and student assent were obtained for each study.

Study 1: Focus Groups

The focus groups were designed to gain a better understanding of reservation life for 7th graders and to evaluate existing BUYOI campaign materials.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Two focus groups with 7th graders – one male and one female - were conducted Spring 2015 in each intervention community. These students would not be included in efficacy testing since this was the year prior to campaign launch. Students were recruited by school and local research staff through class announcements and fliers. Researchers requested 8–12 students per group; however, the mean group size was 7 (minimum of 4 in one group and maximum of 11 in another). Focus groups lasted 45 – 55 minutes, and each participant received $10.

Procedures

At the request of the CACs, the sessions were not recorded; instead, a research staff member took extensive notes. Focus groups began with an assurance of confidentiality and specification of ground rules (e.g., no use of community member names). After icebreaker questions (e.g., what do you do for fun?), the moderator began with a scenario of a 7th grader new to the community who asks them “What’s it like to live here?” and “What are the best (worst) things about living here?”. Students were then asked about local substance use (“What kind of drugs do students use?” “What are the challenges to being drug free?”). Students were also asked about their aspirations for the future and what “Be Under Your Own Influence” meant to them.

The moderator then explained that substance use prevention posters and other materials were being created for 7th graders like them, and their input would help determine the look and content of those materials. Students were asked to rank examples of text and visuals. The text came from posters and other media used in the original campaign, with edits to reflect modern jargon (e.g., “weed” instead of “pot”) and AI history and culture (e.g., replacing Martin Luther King with Sitting Bull). Each sample consisted of a two-word headline (e.g., Future Focus, History Makers) followed by text reflective of the headline. Table 1 gives three examples of text. Participants were asked to read each sample, mark how well they liked it (Like ☺, Neutral  , Dislike☹), and write comments about it. After participants completed the ratings, the moderator facilitated a discussion.

, Dislike☹), and write comments about it. After participants completed the ratings, the moderator facilitated a discussion.

Table 1:

Example Focus Group Headlines and Text

| Future Focus | History Maker | Forever Family |

|---|---|---|

| Fast forward | We are products of our own History. | Why ruin a good thing? |

| To the future and see us then | Pieces of people who have paved the way. | I’ve got expectations to uphold. |

| The way we see us now. | Parents, coaches, teachers, ancestors | Family to make proud. |

| We press play every day. | They have led me to today. | I’d rather see their smiles than feel their disappointment. |

| Learning. Living. Laughing. | It’s our turn now to be | |

| Working hard, getting smart. | History Makers, Ground Breakers. | I don’t use drugs or alcohol. |

| Staying focused, eyes on the prize. | Drugs? | I’ve got goals to reach and people looking up to me to do the right things. |

| Drugs aren’t going to move us forward. | Why choose something that would make me history | |

| There’s no Pause or Stop on the future that is ours. | Instead of a History Maker. |

Participants then ranked photos. CAC feedback about the original BUYOI visuals was used to search within image databases for visuals consistent with AI culture and life. For example, CACs recommended using photos of AI youth playing basketball since basketball is popular on these reservations. Other photos included images that reflected AI culture (e.g., dancers at powwows), sports and other activities, scenery, and family life. Examples of images tested are shown in Figure 1. In the first four focus groups conducted, students ranked groups of related photos (e.g., 4 photos of dancers) from 1 (most liked) to 4 (least liked). The most liked were then grouped into sets of four unrelated photos, and the final two groups rated these photos on a six-point scale.

Figure 1:

Example images tested in focus groups

Note: All photos have been reproduced with permission.

Last, participants were asked about best ways to deliver campaign messages to them and their use of technology (e.g., cell phone) and social media (e.g., Snapchat).

Analysis

Focus group notes were typed with all identifiers removed. To assess open-ended questions, inductive data analysis was used because of limited knowledge from which to formulate a priori codes. A member of the research team used a process of open coding, where notes and codes were written directly into the transcripts. The coder then compiled their notes and codes into separate coding sheets for each question and grouped codes under higher-order headings. A second member of the research team then read the transcripts, reviewed the codes and coding sheets, and identified key themes by question. A third member of the research team reviewed the transcripts, coding sheets, and key themes and made further comments. The research team then collectively reviewed and finalized results. Finally, image and text average ratings/rankings were computed by gender.

Results

Qualitative results

Community Life.

In describing life in their community, the theme of social disorganization emerged, with subthemes of “trash” and “drug and alcohol use”. Students in all groups spoke of the pervasiveness of trash in their communities and how this was different from other places. Quotes included “I don’t like the trash blowing around”; “it’s dirty around here - it makes me feel shame”; and “the tribe needs to come together to do trash collection”. Likewise, comments about the use of drugs and alcohol in their communities were frequent. Quotes included: “there’s lots of drugs around this town”; “…the worst things [about this town] are the drugs and alcohol”; and “you see needles laying around”. Students also noted that their communities have vandalism, abandoned/burnt buildings, and high rates of violence (e.g., “fighting is a big thing”; “you see people fighting on the streets – it affects you”). Several students noted that the violence often comes from substance use. When asked about benefits of living in their community, some students commented on the physical environment and activities available to them (e.g., “I feel at home in the mountains where I hunt”; “it [the town] has … a new skate park and a swimming pool”). One female noted “it was a good place to grow up when I didn’t know there were so many drugs”. When asked about popular activities, frequent responses included basketball and other sports, video games, hunting/fishing, and spending time with family and pets.

Substance use.

Drugs most frequently mentioned as being used in school and the community were marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and alcohol. Several students noted seeing evidence of meth use, e.g., “[people on meth] picking at their face…teeth fallen out”. The predominant themes regarding the challenges to being drug free were the pervasiveness of drug use and peer pressure – both direct and indirect. Students said that with so much substance use, there was a pressure to fit in, even being “bullied” into use. In one community, students mentioned the popularity of ‘branding’ of a ‘bull burn’ to denote a user.

Personal autonomy and aspirations.

In response to the question, “What does Be Under Your Own Influence mean to you?”, the theme of autonomy was evident in all responses (e.g. “you’re in charge of yourself”; “don’t let anyone boss you around”), and students liked the phrase. Regarding aspirations, most students, especially females, said they would attend college. Desired careers included veterinarian, engineer, physical therapist, forestry, police officer, oil field worker, and for one-third of males, basketball player. The students were split on whether they wanted to live on the reservation as adults - some expressed a desire to leave and stay away while others wanted to return after college to give back to family, tribe and community.

Message Delivery.

Students felt that role modeling and personal stories would influence them to be drug- and alcohol-free. Several mentioned family members as excellent role models. Other students noted that they were motivated to not be like community members who drank too much. Finally, when asked about social media platforms, most students used Snapchat and Instagram, and most had a cell phone and computer at home with internet access.

Text and images

Text.

The highest ratings for headlines and text (body copy) across gender were for History Maker, Future Focus, and Dream On. All three (out of 17 total) focused on making good choices to reach goals and build a positive future. Interestingly, in all three, the text referred to “we” instead of “I”, though no participant mentioned that this affected their ratings. This contrasts with the least-liked headlines/text that used “I” and focused on the individual as achiever or different from others (Screamin’ Intense, Original Radical, and Independent Individual). There were several differences by gender. Girls rated Forever Family high while boys rated it relatively low. Conversely, boys rated Outrageous Courageous high while girls rated it low.

Images.

Students generally liked photos that reflected positive aspects of reservation life, e.g., playing basketball, horses, and groups of friends. Photos of dancers at powwows were not generally ranked high except for an adolescent fancy shawl dancer that was top ranked by girls. In general, girls ranked photos with females higher, boys ranked photos with males higher, and both ranked photos with identifiable AIs higher. Finally, one photo of three AI dancers in silhouette of a sunset was highly ranked by males and females.

Study 2 Photovoice

Methods

Participants/recruitment

Participants were high school students in the intervention communities who agreed to serve as role models and deliver campaign messages in their upcoming junior year. School staff recruited 16 role models; ten students completed the photovoice assignment.

Procedures

Participants attended a one-week role model training at the research university in the summer prior to campaign implementation. One month prior to this, research staff held a photovoice workshop in each community, instructing the students on the assignment and teaching ethics and techniques of photo taking. Each participant received three disposable cameras, each labeled with a question: 1) What/who in your environment inspires you to live drug- and alcohol-free? 2) What in your environment challenges you to live drug- and alcohol-free? and 3) What makes you your own individual?. Cameras were brought to the training where photos were developed. Students took between 1 and 11 photos per question, with most taking 3 to 5 photos.

During the summer training, project staff members individually discussed photos with students, following a written guide. Beginning with the first question “what inspires you to be drug and alcohol free?”, participants were asked to select the photo that best exemplified their answer. The interviewer then asked a series of questions to elicit the meaning/story behind the photo (e.g., what is this a photo of; why did you take this photo). When the participant had no more to say, the interviewer had them select a new photo and continued with the same procedure. Most participants discussed a maximum of four photos per question, though several participants discussed up to six. Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes. Interviewers took detailed notes, and after the interviews, these notes were transcribed and organized for analysis.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using the inductive procedures described above.

Results

What inspires you to be drug free?

Students took the most photos for this question. Photos commonly featured activities and hobbies that students preferred to do rather than using drugs, in addition to photos featuring family and friends. Themes were organized into three categories: people, achievement and expression, and culture and traditions.

People.

Every student photographed important people in their lives who inspired them to stay drug and alcohol free. These included family members, friends, peer role models, elders, and in one case, people not to be like. Family inspiration was sometimes expressed in terms of behavioral expectations (“they tell me not to do things like that”), but more often expressed as positive role modeling (e.g., “my great-grandma is drug and alcohol free and she took care of me when I was younger”). Some noted that they wanted to positively influence siblings. Role models also included friends and accomplished older peers. One student photographed an elder care center, saying that elders were an inspiration to stay drug free. Another photographed people hanging out in town, explaining “they inspire me … because I don’t want to be like that”.

Achievement and expression.

Students took photos symbolizing that being drug and alcohol free was necessary to achieve goals and express themselves. Goals included being valedictorian, getting an education, being a leader to younger youth, and getting better at sports. Related to achieving goals, many students noted that being involved in activities (e.g., sports, sewing, music, working with children), especially those they were passionate about, inspired them to be drug and alcohol free.

Culture and traditions.

Several students took photos of reservation land and symbols of their tribal culture. For these students, following traditional ways through learning the language and traditions, being part of ceremonies, and honoring the land as sacred were inspiration to be drug and alcohol free.

What challenges you to be drug and alcohol free?

The fewest photos were taken in response to this question, likely because of safety concerns and instructions to not photograph people without permission and photograph only if considered a positive influence. The theme among photos taken was the substance use that occurs on the reservation. One student noted that being asked regularly to use drugs is a big challenge.

What makes you your own individual?

Three themes were identified: passions, hobbies and activities; style; and belonging to the tribe and its land.

Passions, hobbies, and activities.

A wide variety of activities were photographed, including playing Xbox, riding and caring for horses, being an artist, boxing, basketball, music, poetry, and cross-country running.

Style.

Several students took photos of clothing or items they own and noted that the things they wear or use make them their own individual. One student noted that they liked having a different style and showing others that “you don’t have to fit in; you can be your own person.”

Belonging to their tribe and its land.

Two students took photos of land on their reservation and noted that the land is part of who they are (e.g., “it’s my home … where I come from”). Several students took photos of cultural symbols or indicated that they tried to take a photo of something specific to their culture. One noted “I am [name of tribe]” although he said he could not capture that in a photo.

Discussion

This paper presents formative research findings being used to adapt an existing substance use prevention media campaign, Be Under Your Own Influence, for reservation-based AI youth. Both the target audience, 7th graders, and campaign role models, 11th graders, provided input for adaptation through focus groups and photovoice, respectively. Both age groups noted the pervasiveness of substance use on their reservation, among youth and adults, and that this use posed a major challenge to being drug free. In addition, students often noted negative aspects of living on the reservation - aspects that tied closely to markers of social disorganization (Perkins, Meeks, & Taylor, 1992), with substance use, trash, and violence most frequently mentioned.

Though these students live in unique environments that are geographically remote, they have much in common with majority-culture and other minority youth. Study findings indicated that, like other youth (Johnson, Staff, Patrick, & Schulenberg, 2017; Sirin, Diemer, Jackson, Gonsalves, & Howell, 2004), these students have high future aspirations, with most planning to attend college and/or work toward a career goal. They also participate in a wide variety of activities and hobbies, many of which are popular among other U.S. youth (e.g., music, sports, gaming). A desire to excel in these activities inspired the 11th graders to be drug and alcohol free. Further, social influences of family, friends, and other loved ones, both as positive and negative role models, were important in decisions to not use drugs and alcohol, a finding consistent with social models of adolescent drug use (see, for example, Connell, Gilreath, Aklin, and Brex (2010)).

However, there were important differences between the experiences, environment, and values of these AI youth as compared to youth targeted in the original campaign. These differences, categorized into findings related to surface or deep structure adaptation, represent excellent opportunities for adapting the campaign.

Surface structure adaptation findings

Youth activities.

Although many activities noted by youth were the same as those of majority-culture youth, original BUYOI posters used activities not mentioned by the youth and that CAC members noted as not popular on reservations (e.g., skiing). Study participants singled out basketball as being popular among all age groups, and 7th graders rated an image of AIs playing basketball highly. Other sports such as track, football, volleyball and rodeo were also popular among reservation youth.

Images of people.

CAC members disliked the original campaign images because they did not reflect their community’s youth, either in appearance or in subject matter. They requested local youth be featured in the posters, as they believed this would have more impact with younger adolescents. Focus group participants rated images containing AI youth higher than those showing non-AI youth or youth of indeterminate ethnicity. Photos showing dancers in tribal regalia were not rated highly, with the exception of the fancy shawl dancer mentioned previously. According to AI research staff and CAC members, although many youth participate in powwows and similar tribal events, they are more likely to dress in casual clothes and participate in a variety of ways – as singers, drummers, dancers, or spectators. In addition, powwow regalia is both tribe-specific and reflective of personal style; thus, the images of tribal dancers may have meant little to the youth. On the other hand, a highly rated image was of three traditional AI dancers silhouetted in sunset where tribe, geography, and other identifiers could not be ascertained.

Deep structure adaptation findings

Cultural orientation.

Consistent with other research of indigenous peoples (Beckstein, 2014), findings suggest a more collectivist cultural orientation as compared to an individualistic one. Oyserman (2011) called the cultural frameworks of collectivism and individualism the “best-researched, best-understood, and most general simplifying cultural frameworks”. The U.S. is often described as individualistic where individual initiative is seen as central, and personal achievement is prioritized over group relations and goals. Conversely, a collectivist culture prioritizes group relationships, and social structures exist to support group goals. One finding that simply illustrates a collectivist orientation was the higher ratings of campaign text with “we” versus text using “I”. In addition, the headlines/text least liked were those that might construe individualism or calling attention to oneself (e.g., Independent Individual, Screamin’ Intense, Original Radical). Corroborating this interpretation were comments made during the course of focus group and photovoice discussions. Several youth noted that they would return to their reservation after college to help their people, and in response to an icebreaker question asking “What would you do if you were given $10,000?”, answers were uniformly more collectivist (e.g., “give some to my family”, “take half and help the town”). This is consistent with other research that has found that AI youth often feel a strong sense of obligation both to their families and their home communities, and they value making positive contributions to their people (Fann, 2004). Consistent with a collectivist orientation, youth of both age groups spoke of respect for elders and their importance in passing on the tribe’s culture, traditions and values.

Although the themes of aspirations and autonomy were originally used with majority-culture youth where individualism is more salient, the research findings suggest that a collectivist orientation is consistent with autonomy and aspirations. However, they may be operationalized differently to enhance the well-being of the group instead of the individual. In a study of academic achievement and motivation goals, Ali et al. (2014) found that there were more similarities than differences between Navajo and Anglo students in terms of patterns of relationships between motivation and achievement. However, the Navajo students were relatively lower in competition goals but higher in social concern. In a study of Native youth, McInerney and Swisher (1995) found that key variables predicting measures of school performance and attitudes did not include competitiveness and recognition.

Tribal identity.

The importance of culture and tribal affiliation to student identity and aspirations was another key finding from the photovoice study, and several students noted that learning their tribal language and traditions, participating in ceremonies, and honoring the land as sacred inspired them to be drug and alcohol free. This finding is consistent with research showing that Indigenous youth take pride in their Native language and culture, even when they fear being labelled as backward for displaying that pride (McCarty, Romero, & Zepeda, 2006). This finding is also consistent with a collectivist orientation. For example, in a study of caregiving, Willis (2012) found that strong ethnic identity was associated more with a collectivist orientation compared to an individualistic one.

Delivery of the campaign.

The original intervention did not rely on local role models to deliver campaign messages. Our study findings suggested that campaign localization through delivery by local role models and additional localized posters would be beneficial. While 7th grade students observed widespread substance use in their communities, they also felt that role modeling by peers and others and personal stories would influence them to stay drug and alcohol free. Likewise, 11th grade students took photos of friends, family and other community members, including older peers, as inspiring them to stay drug and alcohol free. The CACs were resolute that local high school students be the predominant role models used in the campaign. With the pervasiveness of substance use in their communities, they felt the campaign should provide students with local examples of drug and alcohol-free youth who are succeeding in their lives.

Adaptations

The findings above led to the following surface and deep structure adaptations of the original campaign that are currently being tested in the field. While significant adaptations were made, the original themes of autonomy and aspirations, along with the BUYOI tagline, underlay all campaign messaging, with messages delivered, in part, through the same traditional media channels as the original campaign.

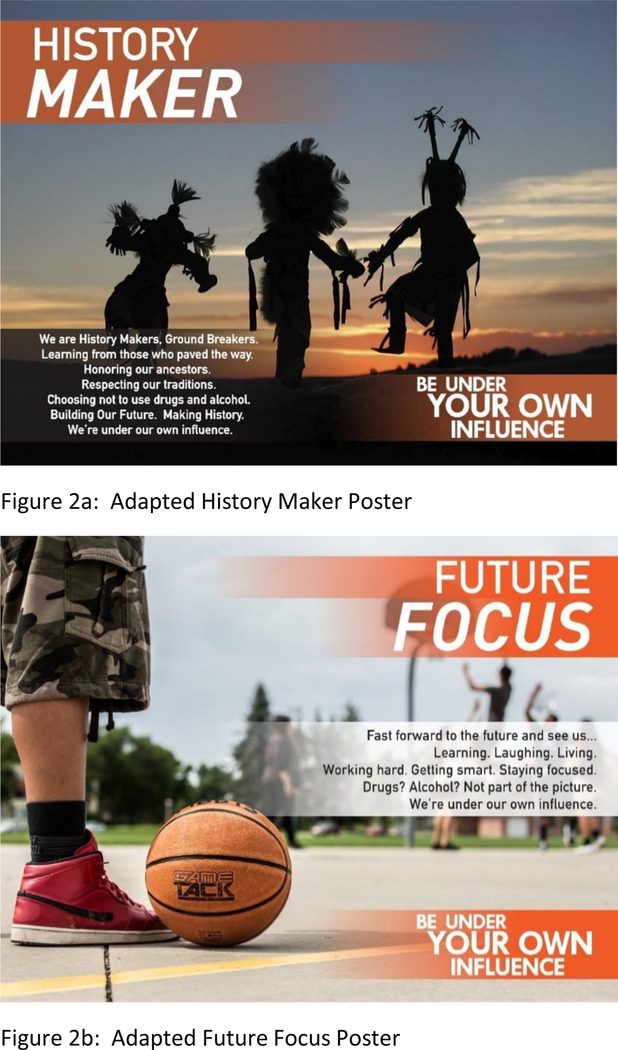

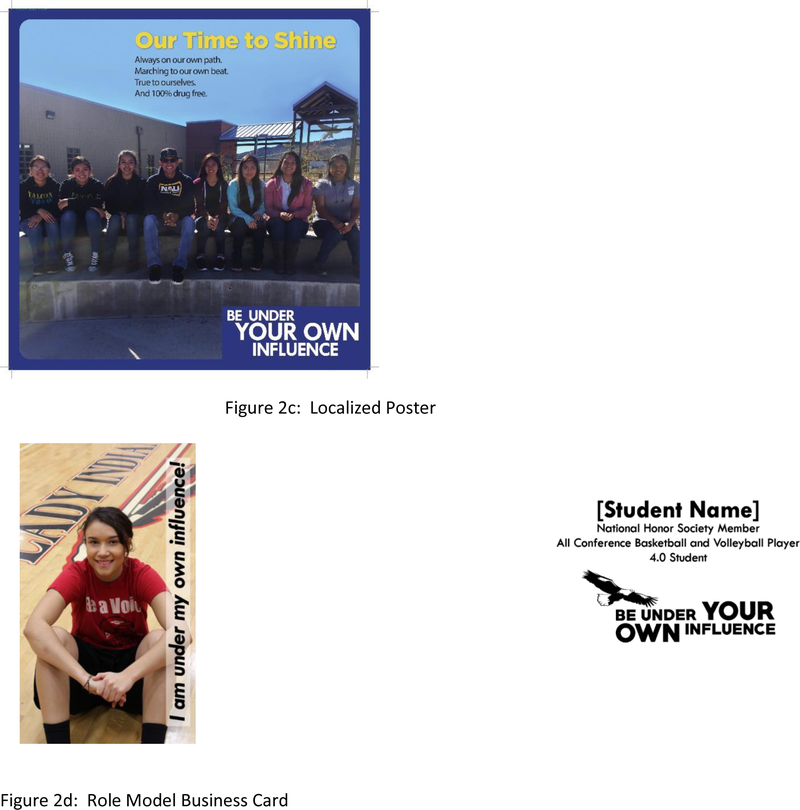

Surface Structure - Images.

All images from the original BUYOI campaign were replaced with images reflective of American Indians and their environment and culture (see Figures 2a and 2b for examples).

Figure 2:

Example adapted posters created for American Indian BUYOI campaign

Note: Figure 2a photo reproduced with permission. Parental and youth consent was obtained for use of photos in Figures 2b, 2c and 2d.

Deep Structure - Messages.

New messaging focusing on finding strength in one’s tribal history, culture, and identity, consistent with a collectivist orientation, were created. Figure 2a is an example of this. Role models also used variations of this text as school announcements, at events, and, in one community, as radio ads on the local station.

Deep Structure - Localization.

It became clear throughout the formative research process that localization would be key to an effective, impactful campaign. Thus, the number of localized posters featuring the 11th grade role models was increased, and most campaign messages were delivered through various channels by these students. Figure 2c shows one localized poster - Our Time to Shine. Other localized posters featured one or more role models, with appropriate headlines (e.g., Fierce Friends) and text. Each role model had a business card with photo, descriptors and campaign tagline (Figure 2d). Campaign delivery is also being adapted so that role models meet with 7th graders at assemblies, class presentations and other events, presenting content focused on BUYOI themes and personalized to their life stories.

Limitations

As with much formative research, the focus group and photovoice participants do not represent random samples of the targeted groups nor are the participating AI reservations necessarily representative of all reservations. However, the reservations are located in the NP and SW cultural regions that encompass the majority of reservation AIs and, within each region, share cultural attributes (Snipp, 2005). Moreover, these reservations are similar in socioeconomic status to other reservations in these regions. For example, 2011–2015 poverty rates were 30%, 37.7%, and 46.0% compared to an average poverty rate of 37% for the 20 largest reservations within these regions (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011–2015). In addition, two focus groups and the photovoice had fewer participants than ideal. However, there were many similarities in results across the three reservations, and findings were consistent with the sparse findings from other research. This suggests that reservation-based AI youth share many similarities across tribes.

Conclusions

The formative research findings guiding adaptation of the BUYOI substance use prevention campaign showed that reservation-based AI youth share many similarities with other U.S. youth. In particular, they are achievement-oriented, with future aspirations similar to other youth, and most see being drug and alcohol-free as necessary to making good decisions and achieving their goals. Thus, the campaign themes of autonomy and aspirations are a good fit for this population. On the other hand, these youth differ in significant ways, for example, through culture and history, environment, and geography. Therefore, both surface and deep structure adaptations of the campaign are needed to make it relevant and inspiring to these youth. The findings of this study highlight the need to consider both types of adaptations to health communications campaigns and other prevention/intervention programs targeted to AI audiences. Our results also suggest that qualitative techniques such as focus groups and photovoice are appropriate within this population for identifying these needed adaptations.

Contributor Information

Linda R. Stanley, Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1879, 970-491-1765.

Kathleen J. Kelly, Department of Marketing, Director of the Center for Marketing & Social Issues, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-970-491-7483.

Randall C. Swaim, Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1879, 970-491-6961.

Danielle Jackman, Aurora Research Institute, Aurora Mental Health Center, 11059 E. Bethany Drive, Aurora CO 80013, 303-923-6560.

References

- Ali J, McInerney DM, Craven RG, Yeung AS, & King RB (2014). Socially oriented motivational goals and academic achievement: Similarities between Native and Anglo Americans. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(2), 123–137. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2013.788988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anker AE, Feeley TH, McCracken B, & Lagoe CA (2016). Measuring the effectiveness of mass-mediated health campaigns through meta-analysis. Journal of Health Communication, 21, 439–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M Jr., Castro FG, Strycker LA, & Toobert DJ (2013). Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(2), 196–205. doi: 10.1037/a0027085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstein A (2014). Native American subjective happiness: An overview. Indigenous Policy Journal, 25(2). [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0016401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brazg T, Bekemeier B, Spigner C, & Huebner CE (2011). Our community in focus: the use of photovoice for youth-driven substance abuse assessment and health promotion. Health Promotion Practice, 12(4), 502–511. doi: 10.1177/1524839909358659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleden H, Garvin T, & First Nation H (2008). Modifying Photovoice for community-based participatory Indigenous research. Social Science and Medicine, 66(6), 1393–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Gilreath TD, Aklin WM, & Brex RA (2010). Social-ecological influences on patterns of substance use among non-metropolitan high school students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(0), 36–48. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9289-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, & Grant BF (2008). Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 2149–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fann A (2004). Forgotten students: American Indian high school students’ narratives on college going (Unpublished document for a Research Colloquium). UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Higher Education, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, & Chadwick B (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6), 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Bang H, & Botvin GJ (2010). Age of alcohol and marijuana use onset predicts weekly substance use and related psychosocial problems during young adulthood. Journal of Substance Use, 15, 174–183. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Staff J, Patrick ME, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Adolescent adaptation before, during and in the aftermath of the Great Recession in the USA. International Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 9–18. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper-Reeves L, Dustman PA, Harthun ML, Kulis S, & Brown EF (2014). American Indian cultures: How CBPR illuminated intertribal cultural elements fundamental to an adaptation effort. Prevention Science, 15(4), 547–556. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0361-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ (2005). The effects of developmental mentoring and high school mentors’ attendance on their younger mentees’ self-esteem, social skills, and connectedness. Psychology in the Schools, 42(1), 65–77. doi: 10.1002/pits.20025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K, Comello MLG, & Slater M (2006). Development of an aspirational campaign to prevent youth substance use: “Be under your own influence.” Social Marketing Quarterly, 12, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty TL, Romero ME, & Zepeda O (2006). Reclaiming the gift: Indigenous youth counter-narratives on Native language loss and revitatlization. The American Indian Quarterly, 30(1&2), 28–48. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2006.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney DM, & Swisher KG (1995). Exploring Navajo Motivation in School Settings. Journal of American Indian Education, 34(3), 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D (2011). Culture as situated cognition: Cultural mindsets, cultural fluency, and meaning making. European Review of Social Psychology, 22(1), 164–214. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2011.627187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DD, Meeks JW, & Taylor RB (1992). The physical environment of street blocks and resident perceptions of crime and disorder: Implications for theory and measurement. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(1), 21–34.doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80294-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson-Sweeney K (2005). The use of focus groups in pediatric and adolescent research. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 19(2), 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2004.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, & Braithwaite RL (1999). Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity & Disease, 9(1),10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR, Diemer MA, Jackson LR, Gonsalves L, & Howell A (2004). Future aspirations of urban adolescents: a person‐in‐context model. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 17(3), 437–456. doi: 10.1080/0951839042000204607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD (2006). Specification and misspecification of theoretical foundations of logic models for health communication campaigns. Health Communication, 20(2), 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Kelly KJ, Edwards RW, Thurman PJ, Plested BA, Keefe TJ, … Henry KL. (2006). Combining in-school and community-based media efforts: reducing marijuana and alcohol uptake among younger adolescents. Health Education Research, 21(1), 157–167. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Kelly KJ, Lawrence FR, Stanley LR, & Comello MLG (2011). Assessing Media Campaigns Linking Marijuana Non-Use with Autonomy and Aspirations: “Be Under Your Own Influence” and ONDCP’s “Above the Influence”. Prevention Science, 12(1), 12–22. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0194-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipp CM (2005). American Indian and Alaska Native Children: Results from the 2000 Census. Population Reference Bureau: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley LR, & Swaim RC (2015). Initiation of alcohol, marijuana, and inhalant use by American-Indian and white youth living on or near reservations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 155, 90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaim RC (2017). Substance Use Prevention Campaign for American Indian Youth. Identification No. NCT03051633. Retrieved from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT03051633.

- Swaim RC, & Stanley LR (2018). Substance use among American Indian youths on reservations compared with a national sample of US adolescents. JAMA Network Open, 1(1), e180382. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2011–2015). Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months: 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. 2011–2015 Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/guided_search.xhtml.

- Vangeepuram N, Carmona J, Arniella G, Horowitz CR, & Burnet D (2015). Use of Focus Groups to Inform a Youth Diabetes Prevention Model. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47(6), 532–539.e531. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield MA, Loken B, & Hornik RC (2010). Use of mass media campaigns to change health behavior. Lancet, 376(9748), 1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC (2006). Youth Participation in Photovoice as a Strategy for Community Change. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1–2), 147–161. doi: 10.1300/J125v14n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis R (2012). Individualism, collectivism and ethnic identity: cultural assumptions in accounting for caregiving behaviour in Britain. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 27(3), 201–216. doi: 10.1007/s10823-012-9175-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, & Miller RL (2003). Examining strategies for culturally grounded HIV prevention: A review. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15(2), 184–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]