Abstract

Objective:

We investigated whether internalized HIV-related stigma predicts adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) longitudinally in women living with HIV in the United States, and whether depression symptoms mediate the relationship between internalized stigma and sub-optimal ART adherence.

Design:

Observational longitudinal study utilizing data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) cohort.

Methods:

A measure of internalized HIV-related stigma was added to the battery of WIHS measures in 2013. For current analyses, participants’ first assessment of internalized HIV-related stigma and assessments of other variables at that time were used as baseline measures (Time 1 or T1, visit occurring in 2013/14), with outcomes measured approximately two years later (T3, 2015/16; n=914). A measure of depression symptoms, assessed approximately 18 months after the baseline (T2, 2014/15), was used in mediation analyses (n=862).

Results:

Higher internalized HIV-related stigma at T1 predicted lower odds of optimal ART adherence at T3 (AOR = 0.61, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.45,0.82]). Results were similar when ART adherence at T1 was added as a control variable. Mediation analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of internalized HIV stigma at T1 on ART adherence at T3 through depression symptoms at T2 (while controlling for depression symptoms and ART adherence at T1; B = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.11,−0.006]).

Conclusions:

These results provide strong longitudinal support for the hypothesis that internalized HIV-related stigma results in sub-optimal ART adherence in a large sample of women living with HIV in the United States, working through the pathway of increased depression symptoms.

Keywords: Adherence, stigma, depression, internalized, women

Introduction:

Despite effective treatments for HIV, treatment adherence and viral suppression remain sub-optimal among many people living with HIV (PLWH), especially for certain subgroups, including Black and Latina women.[1, 2] Identifying and addressing psychosocial barriers to ART adherence—such as internalized stigma, when people living with HIV endorse and accept negative attitudes about people living with HIV[3]—are vital to enhancing rates of ART adherence and viral suppression.

A large body of research—mainly composed of cross-sectional and qualitative studies—suggests that HIV-related stigma is associated with sub-optimal adherence to medication and HIV clinic visits,[4–8] including studies of women living with HIV in the US.[9] Both conceptual frameworks and empirical work suggest internalized HIV stigma has a stronger relationship with ART adherence than other dimensions of HIV-related stigma (anticipated, perceived community, and enacted).[3, 10] Furthermore, cross-sectional research suggests that for women, the association between internalized stigma and ART adherence is mediated by depression symptoms.[10]

A comprehensive systematic review of stigma and ART adherence identified only seven longitudinal studies in the global literature and six of these reported null findings on the relationship between HIV-related stigma and treatment adherence.[4] One of these longitudinal studies found that individuals who reported higher levels of HIV-related stigma were more likely to self-report missed medications.[11] In another article presenting meta-analyses of HIV-related stigma and health outcomes, 9 additional longitudinal studies were identified (out of 120 included studies), but none focused on ART adherence as an outcome.[5] A recent review by Sweeney et al., focusing specifically on HIV-related stigma and ART adherence, identified only 5 additional longitudinal studies (out of 38 in the review), 2 in the US and 3 in Africa or Asia. The two longitudinal studies conducted in the United States did not find significant associations of stigma with non-adherence.[7]

Relatively few studies have a specific focus on internalized HIV-related stigma, and several use lack of disclosure as a proxy for stigma, instead of measuring stigma explicitly. Furthermore, prior studies in this area have been conducted with predominantly male and Caucasian samples,[7, 12] with a few notable exceptions.[13, 14] Thus, additional longitudinal research is needed on the effects of internalized HIV-related stigma on ART adherence as well as on mediating mechanisms, especially in women and in racial/ethnic minority populations, who are disproportionately affected by HIV.

The purpose of the present longitudinal study was to investigate whether internalized HIV-related stigma predicts sub-optimal ART adherence in women living with HIV. Because studies have supported links between internalized HIV-related stigma, depression symptoms, and ART adherence,[15, 16] we also examined the hypothesis that depression symptoms mediate the effect of internalized HIV stigma on ART adherence. To design effective supportive interventions, it is necessary to understand the causal mechanisms linking internalized stigma with sub-optimal ART adherence over time.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected from women living with HIV participating in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS).[17, 18] WIHS is a multi-site prospective study investigating HIV disease progression, co-morbidities, and the behavioral impact of HIV infection among women in the US. Since 1994, data have been collected from participants in six US sites (Bronx, Brooklyn, Washington DC, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco) every 6 months via interviews, physical assessments, and laboratory tests. To further enhance the representativeness of the cohort, new participants were enrolled between 2013–2015 at sites in the US South; including Atlanta, Birmingham, Jackson, Miami, and Chapel Hill. The median age of WIHS participants is 50 years. Around 75% of HIV-positive WIHS participants identify as African-American, 14% as White, and 14% as Hispanic. All participants provided written informed consent, with study activities being approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board.

A measure of internalized HIV-related stigma was added to the battery of WIHS measures in 2013. For current analyses, participants’ first assessment of internalized HIV-related stigma and assessments of other variables at that time were used as baseline measures (Time 1 or T1, visit occurring in 2013/14). The follow-up date was approximately two years later (T3, 2015/16). For most participants, a measure of depression symptoms assessed at approximately 18 months after the baseline (T2, 2014/15) was available and used in mediation analyses. A total of 914 HIV-positive WIHS participants were on ART at baseline and had complete data on these variables at T1 and T3 (as well as relevant covariates) for the longitudinal analyses, and 862 had complete data for the mediation analyses (T1, T2, and T3; see Footnotes to Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Correlations, and Adjusted Relationships of Time 1 (T1) Predictors with ART adherence at Time 3a

| Sample characteristics (n=965) |

Correlation with internalized HIV stigmab | Correlation with depression symptoms at T3b | Without adjustment for ART adherence at T1c (n=914) | With adjustment for ART adherence at T1c (n=914) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Predictors | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | ||

| Internalized HIV stigma | 1.76 (0.62) | - | .33** | 0.61 | 0.45–0.82 | 0.64 | 0.47–0.87 |

| Age (years) | 49.11 (8.51) | −.08* | .01 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.05 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 |

| Time on ART (years) | 11.07 (6.38) | −.18** | −.10** | 0.96 | 0.92–0.99 | 0.96 | 0.93–1.00 |

| Use of illicit drugs | 220 (22.8%) | .06 | .20** | 0.51 | 0.34–0.77 | 0.60 | 0.39–0.93 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 114 (11.8%) | .01 | .05 | 4.13 | 1.73–9.88 | 3.66 | 1.51–8.85 |

| Household Income >$12,000 | 450 (46.6%) | −.05 | −.19** | 0.89 | 0.60–1.32 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.27 |

| More than high school education | 329 (34.1%) | −.02 | −.11** | 0.89 | 0.59–1.34 | 0.92 | 0.60–1.39 |

| Region US Southd | 140 (14.5%) | .21** | .10** | 1.23 | 0.64–2.35 | 1.19 | 0.61–2.32 |

| ART adherence at T1 (optimal) | 831 (86.1%) | −.06 | −.08** | − | - | 4.01 | 2.61–6.30 |

| Depression symptoms at T1 | 12.26 (11.30) | .37** | - | - | - | - | - |

a Of the 965 participants, only one participant did not have data on internalized stigma, and 50 did not have data on ART adherence at T3. Participants with data on ART adherence at T3 who were included in the analysis (n=914) did not differ from 50 participants who did not have data on ART adherence at T3 on internalized stigma or any of the covariates (all p values > .19) and listwise deletion was used in analyses.

b Associations with binary variables are also reported as correlation coefficients instead of t-tests in order to simplify presentation. Note that a t test and a correlation test yield the same p value.

c Estimates adjusted for all other T1 predictors listed in the table, except for depression symptoms, which was entered in the mediation analysis.

d Region: US South/Southeast versus Other US Regions.

* p < .05;

** p < .01

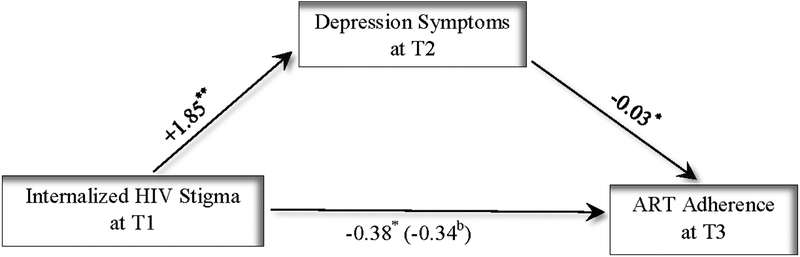

Figure 1.

Depression symptoms at T2a mediate the effect of internalized HIV-related stigma at T1 on ART adherence at T3 (n=862)

Note. Associations are presented as path coefficients (unstandardized). Depression symptoms and ART adherence at T1 (as well as the covariates race, age, time on ART, illicit drug use, income, education, and region) were also entered as control variables.

a Fifty two participants did not have data on depression symptoms at T2 or T1. These 52 participants did not differ from the participants included in the mediation analysis, on internalized stigma or any of the covariates (all p values > .10), and listwise deletion was used.

b When depression at T2 is in the model.

* p < .05; ** p < .01

Measures

Adherence:

Participants self-reported how often they took their ART as prescribed over the past 6 months. Response options were “100% of the time”, “95–99% of the time”, “75–94% of the time”, “<75% of the time”, and “I haven’t taken any of my prescribed medications”. Previous research provides support for the validity of this measure of adherence.[19, 20] As in previous studies, we dichotomized the measure at 95% or higher versus lower than 95%.[20, 21]

Internalized HIV-related Stigma:

This was assessed with the negative self-image subscale of the revised HIV Stigma Scale (range 1–4), which consists of 7 items (e.g., “I feel I’m not as good as others because I have HIV.”), rated on a 4-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree).[22, 23] Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86 in the current sample.

Depression symptoms:

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale[24] is used to assess depression symptoms in the WIHS. In previous studies, depression symptoms, as measured by CES-D, have been shown to predict ART adherence.[25, 26]

Analytical Methods

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the association between internalized HIV stigma at T1 and ART adherence at T3. The following variables (measured at T1), which have been found important when examining ART adherence in previous research,[27–30] were included as covariates: ethno-racial identity, age, time on ART, illicit drug use, income, education, and US region (south vs. other locations). Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) controlling for these covariates are reported. Next, ART adherence at T1 was also added to the model as a control variable. Finally, mediation analysis using bootstrapping (with the program PROCESS, a macro used with SPSS[31]) was conducted to test whether the association between internalized stigma at T1 and ART adherence at T3 is mediated by depression symptoms at T2. This analysis controlled for depression symptoms and ART adherence at T1 (as well as the covariates). A significant indirect effect indicates mediation.

Results

Sample characteristics and associations of covariates with stigma and depression symptoms at T3 are presented in Table 1. Sub-optimal adherence at T3 was reported by 14.1% of the sample. As can be seen in Table 1, higher internalized HIV-related stigma at T1 predicted lower odds of optimal ART adherence at T3 (AOR = 0.61, p = .001, 95%, CI [0.45,0.82]). When ART adherence at T1 was added as a control variable, internalized HIV-related stigma at T1 again predicted lower odds of optimal ART adherence at T3 (AOR = 0.64, p = 0.005, 95%, CI [0.47,0.87]).

Mediation analysis (see Figure 1) revealed a significant indirect effect of internalized HIV stigma at T1 on sub-optimal ART adherence at T3 through depression symptoms at T2 (while controlling for depression symptoms and ART adherence at T1; B = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.11,−0.006]).

Discussion:

These results in a large sample of women living with HIV in multiple locations across the United States provide strong longitudinal support for the hypothesis that internalized HIV-related stigma results in sub-optimal ART adherence. Contrary to some prior longitudinal studies, we found a significant relationship between HIV-related stigma and ART adherence. Our focus on internalized HIV-related stigma was likely a key reason, as internalized stigma tends to have a stronger relationship with ART adherence behaviors than other dimensions of HIV-related stigma, both theoretically and empirically.[3, 10, 32] Furthermore, we found that depression symptoms mediate the effect of internalized HIV stigma on suboptimal ART adherence (again using longitudinal analyses to preserve the temporal sequence among the independent variable, mediator, and outcome variable), providing evidence for the contention that internalized HIV-related stigma affects adherence through depression.

These results add to the evidence from cross-sectional analyses of data from women living with HIV in the US[32] and Canada (which found that depression mediates the pathways from negative self-image to current ART use and ART adherence[14]). These relationships are likely to be relevant for other populations as well. Among gay and bisexual men living with HIV, recent results from an experience sampling method study (in which participants report on their experiences in real-time on repeated occasions) revealed that experiences of internalized HIV-related stigma were concurrently associated with depressed and anxious affect, anger, and emotion dysregulation.[33]

Our results have important implications for interventions to improve ART adherence and HIV-related health for women living with HIV. Addressing HIV-related stigma early in the diagnosis and treatment initiation process may be a key to reducing risk for depressive symptoms and sub-optimal adherence.[3] Acceptance-based approaches may be effective for reducing internalized HIV-related stigma,[34] and can be tailored for brief interventions in HIV care settings. Elucidation of depression as an important intervening mechanism can also provide targets for interventions and supportive services. Depression interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy, have yielded promising results in improving ART adherence.[35–37] Thus, future intervention studies should examine long-term effectiveness of programs specifically tailored for women living with HIV, which address depression and internalized stigma simultaneously.

The current study has limitations. The WIHS is a sample of older women participating in an interval cohort study at urban research centers, and may not be representative of the general population of women living with HIV in the US. The WIHS southern sites were not fully enrolled at T1 for the current study, so fewer of their participants could be included in these analyses. In addition, the outcome measure of ART adherence is based on self-report and may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. However, brief self-report measures of ART adherence have been found to be robust and reliable.[38] In addition, ART adherence and other health behaviors are likely to be influenced by other psychosocial factors (such as self-efficacy, attachment styles, and intersectional and structural stigma and discrimination),[39–42] which are not measured in the national WIHS data collection and therefore are not captured in the current analyses. Future research and programs can extend this work to examine clinical outcomes and utilize these findings to develop, investigate, and evaluate interventions to reduce stigma, address depression, and improve the mental and physical health of women living with HIV.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the assistance of the WIHS program staff and the contributions of the participants who enrolled in this study. This study was funded by Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) sub-study grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, R01MH104114 and R01MH095683. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA), and P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR). This research was also supported by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center for AIDS Research CFAR, an NIH funded program (P30 AI027767) that was made possible by the following institutes: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, and OAR. Trainee support was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number T32HS013852).

References:

- 1.Crepaz N, Tang T, Marks G, Hall HI. Viral suppression patterns among persons in the United States with diagnosed HIV infection in 2014. Ann Intern Med 2017; 167(6):446–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Increased Transmission and Outbreaks of Measles - European Region, 2011 In: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing Mechanisms Linking HIV-Related Stigma, Adherence to Treatment, and Health Outcomes. Am J Public Health 2017; 107(6):863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16(3 Suppl 2):18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016; 6(7):e011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The Association of Stigma with Self-Reported Access to Medical Care and Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24(10):1101–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The Association of HIV-Related Stigma to HIV Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS and Behavior 2016; 20(1):29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice WS, Crockett KB, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Atkins GC, Turan B. Association Between Internalized HIV-Related Stigma and HIV Care Visit Adherence. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2017; 76(5):482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turan B, Rogers AJ, Rice WS, Atkins GC, Cohen MH, Wilson TE, et al. Association between Perceived Discrimination in Healthcare Settings and HIV Medication Adherence: Mediating Psychosocial Mechanisms. AIDS and Behavior 2017; 21(12):3431–3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV Stigma Mechanisms and Well-Being Among PLWH: A Test of the HIV Stigma Framework. AIDS Behav 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dlamini PS, Wantland D, Makoae LN, Chirwa M, Kohi TW, Greeff M, et al. HIV Stigma and Missed Medications in HIV-Positive People in Five African Countries. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 2009; 23(5):377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Simoni JM, Kitahata MM, et al. A Structural Equation Model of HIV-Related Stigma, Depressive Symptoms, and Medication Adherence. AIDS and Behavior 2012; 16(3):711–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logie CH, Wang Y, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wagner AC, Kaida A, Conway T, et al. HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Prev Med 2018; 107:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wang Y, Kaida A, Conway T, Webster K, et al. Pathways From HIV-Related Stigma to Antiretroviral Therapy Measures in the HIV Care Cascade for Women Living With HIV in Canada. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 77(2):144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao D, Feldman B, Fredericksen R, Crane P, JM S. A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS and Behavior 2012; 16:611–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turan B, Smith W, Cohen MH, Wilson TE, Adimora AA, Merenstein D, et al. Mechanisms for the Negative Effects of Internalized HIV-Related Stigma on Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Women: The Mediating Roles of Social Isolation and Depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 72(2):198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005; 12(9):1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, Greenblatt RM, Kempf M-C, Tien PC, et al. Cohort Profile: The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol 2018; 47(2):393–394i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Safren SA, Mugavero MJ, Willig JH, et al. Evaluation of the single-item self-rating adherence scale for use in routine clinical care of people living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2013; 17(1):307–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, Coady W, Hardy H, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav 2008; 12(1):86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dale S, Cohen M, Weber K, Cruise R, Kelso G, Brody L. Abuse and resilience in relation to HAART medication adherence and HIV viral load among women with HIV in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014; 28(3):136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, Forehand R. Measurement of Stigma in People with HIV: A Reexamination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Education and Prevention 2007; 19(3):198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health 2001; 24(6):518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenore Sawyer R The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977; 1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyer-Viola LA, Corless IB, Webel A, Reid P, Sullivan KM, Nichols P. Exploring predictors of medication adherence among HIV positive women in North America. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing : JOGNN / NAACOG 2014; 43(2):168–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitzel LD, Vanable PA, Brown JL, Bostwick RA, Sweeney SM, Carey MP. Depressive Symptoms Mediate the Effect of HIV-Related Stigmatization on Medication Adherence Among HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior 2015; 19(8):1454–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, Shen J, Goggin K, Reynolds NR, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: findings from the MACH14 study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012; 60(5):466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beer L, Skarbinski J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults in the United States. AIDS Educ Prev 2014; 26(6):521–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Wilson TE, Adedimeji A, Merenstein D, Milam J, Cohen J, et al. The Impact of Substance Use on Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Infected Women in the United States. AIDS Behav 2018; 22(3):896–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burch LS, Smith CJ, Phillips AN, Johnson MA, Lampe FC. Socioeconomic status and response to antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a literature review. AIDS 2016; 30(8):1147–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sweeney S, Vanable P. The Association of HIV-Related Stigma to HIV Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS Behav 2016; 20:29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rendina HJ, Millar BM, Parsons JT. The critical role of internalized HIV-related stigma in the daily negative affective experiences of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. J Affect Disord 2018; 227:289–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinta MD, Lezama M, Wells G, Dilley JW. Acceptance and compassion-based group therapy to reduce HIV stigma. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2015; 22(4):481–490. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol 2009; 28(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012; 80(3):404–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spaan P, van Luenen S, Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Psychosocial interventions enhance HIV medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of health psychology 2018:1359105318755545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav 2006; 10(3):227–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African-American men with HIV. Ann Behav Med 2010; 40(2):184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seghatol-Eslami VC, Dark HE, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM, Turan B. Interpersonal and intrapersonal factors as parallel independent mediators in the association between internalized HIV stigma and ART adherence. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2017; 74:e18–e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med 2007; 30(5):359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turan B, Crockett KB, Kempf M-C, Konkle-Parker DJ, Wilson T, Tien P, et al. Internal Working Models of Attachment Relationships and HIV Outcomes among Women Living with HIV. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]