Abstract

The association of BRAF V600E mutation and the presence of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) and microsatellite instability (MSI) often confound analysis of BRAF mutation status and survival in colorectal carcinoma. We evaluated a consecutive series of proximal colonic ad-enocarcinomas for mismatch repair protein abnormalities/MSI, BRAF V600E mutation, and KRAS mutations in an attempt to determine the prognostic significance of these abnormalities and to correlate histopathologic features with molecular alterations. Of the 259 proximal colon adenocarcinomas analyzed for mismatch repair protein abnormalities and/or MSI, 181 proximal colonic adenocarcinomas demonstrated proficient DNA mismatch repair using either MSI PCR (n = 78), mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry (n = 91), or both MSI PCR and mismatch repair immunohistochemistry (n = 12); these were tested for the BRAF V600E mutation and KRAS mutations. Compared with BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas, BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas more frequently demonstrated adverse histologic features such as lymphatic invasion (16/20, 80% vs. 75/161, 47%; P = 0.008), mean number of lymph node metastases (4.5 vs. 2.2; P = 0.01), perineural invasion (8/20, 40% vs. 13/161, 8%; P = 0.0004), and high tumor budding (16/20, 80% vs. 83/161, 52%; P = 0.02). BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas frequently contained areas with mucinous histology (P = 0.0002) and signet ring histology (P = 0.03), compared with KRAS-mutated and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas. Clinical follow-up data were available for 173 proximal colonic adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair. Patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas had a median survival of 12.3 months with a 1-year probability of survival of 54% and a 1-year disease-free survival of 56%. Patients with KRAS-mutated and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas had significantly improved overall survival (unadjusted log-rank P = 0.03 and unadjusted log-rank P = 0.0002, respectively) and disease-free survival (unadjusted log-rank P = 0.02 and unadjusted log-rank P = 0.02, respectively) compared with patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas. When adjusting for tumor stage, survival analysis demonstrated that patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinoma had a significantly poor overall survival and disease-free survival (hazard ratios 6.63, 95% CI, 2.60–16.94; and 6.08, 95% CI, 2.11–17.56, respectively) compared with patients with KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas. No significant difference in overall or disease-free survival was identified between patients with KRAS-mutated and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas. Our results demonstrate that BRAF-mutated proximal colon adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair have a dismal prognosis with an aggressive clinical course and often display mucinous differentiation, focal signet ring histology, and other adverse histologic features such as lymphatic and perineural invasion and high tumor budding.

Keywords: BRAF, KRAS, MSI, mismatch repair, colon, adenocarcinoma, proximal

The predictive power of mutation analysis of the Ras/Raf/MAPK signaling pathway in colorectal carcinoma and response to antiepidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy have been well established.1,10,16,22 Mutations in KRAS are observed in 30% to 40% of colorectal carcinomas and lead to a constitutively activated kinase resulting in EGFR-independent inactivation of the MAPK pathway.5,12,47 Indeed, most studies have shown that activating KRAS mutations predict a lack of response to the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab.1,16,22 BRAF is another component of the Ras/Raf/MAPK signaling pathway that is also frequently mutated in colorectal carcinoma but has a lower prevalence in colorectal carcinoma, seen in approximately 15% to 17% of colorectal carcinomas.30,46 BRAF V600E mutations are frequently observed in colorectal carcinomas demonstrating high levels of promoter methylation of CpG islands (CIMP-high, CIMP-H), with approximately 60% to 80% of CIMP-H tumors harboring mutations in BRAF.3,26,30 These BRAF-mutated CIMP-H colorectal carcinomas are also often characterized by high levels of microsatellite instability (MSI-H) due to the presence of a CpG island in the promoter region of the mismatch repair gene MLH1.8,48 Recent evidence suggests that activating BRAF V600E mutations also predict lack of response to anti-EGFR therapy.10

The prognostic importance of mutations in the EGFR signaling pathway is not entirely clear, with conflicting data reported in the literature. In some studies, the presence of KRAS mutations is associated with shorter survival.2,4,35 However, in these series demonstrating survival differences in KRAS mutated colorectal carcinoma, there are conflicting data on whether codon 122,4 or codon 1335 KRAS mutations confer prognostic significance. Most literature data indicate no survival difference between KRAS wild-type and KRAS-mutated colorectal carcinomas.29,34 Assessing the importance of BRAF mutation status and prognosis is made much more difficult given the close association of BRAF V600E mutations and the presence of CIMP-H and sporadic MSI-H.8,48 MSI-H status is generally associated with improved overall and disease-free survival,31 although not all studies have verified the association of MSI-H and improved overall survival.23 Thus, the presence of MSI-H often confounds analysis of BRAF mutation status and survival in colorectal carcinoma. The studies analyzing both MSI and BRAF mutation status have shown that BRAF V600E mutation is associated with poor survival in microsatellite-stable tumors but has no effect on the improved survival of MSI-H colorectal adenocarcinomas.20,30,36 In contrast, the reports in the literature that did not analyze the prognostic significance of BRAF status independent of MSI status failed to identify an association between BRAF V600E mutation and reduced survival.17,20,33 In addition, most studies lack a rigorous analysis of the histopathologic features of the colorectal carcinomas included, and correlation of the histopathologic findings with mutation status in the EGFR signaling pathway is often not performed.

We analyzed proximal colon adenocarcinomas for mismatch repair protein abnormalities/MSI, BRAF V600E mutation, and KRAS mutations in an attempt (1) to determine the prognostic significance of mutations in the EGFR signaling pathway and (2) to correlate histopathologic features with molecular alterations. We limited our analysis to proximal colonic adenocarcinomas, as the molecular pathway to colorectal carcinoma appears distinct in the proximal and distal colon.30,36 Our results indicate that proximal colon adenocarcinomas with BRAF mutations have distinct morphologic characteristics and that BRAF-mutated proximal colonic adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair are associated with an aggressive clinical course.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Group

The clinicopathologic records of 181 patients with primary invasive adenocarcinoma of the proximal colon, including the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon, accessioned at the Departments of Pathology at Stanford University Hospital for the years 2005 to 2010 and at Cleveland Clinic from 2009 to 2010, were reviewed. Specifically excluded from this study were neuroendocrine tumors and adenocarcinomas of the appendix. Further, 8 subjects did not have adequate information to determine vital status and/or date of last contact. Therefore, the survival analysis was limited to 173 proximal colonic adenocarcinomas. Pathology reports and hospital charts were reviewed, and the following information was obtained: type of initial surgical procedure and the anatomic extent of tumor spread at initial presentation. Intraoperative and clinical follow-up data were obtained from hospital and clinic charts under the guidelines of the Stanford University and Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Boards.

Pathologic Evaluation

A total of 727 (341 Stanford cases, 397 Cleveland Clinic cases) primary colorectal adenocarcinomas were surgically resected for the years 2005 to 2010 at Stanford University and from 2009 to 2010 at Cleveland Clinic. Of these, 259 were primary to the proximal colon, including 137 cases seen at Stanford University and 122 cases seen at Cleveland Clinic Hospital. All available cases of adenocarcinoma of the proximal colon with proficient DNA mismatch repair were histologically reviewed (n = 181), and the following histologic features were recorded for each tumor: grade, extent of invasion, lymph node metastases, status of margin of resection, lymphatic invasion, perineural invasion, venous invasion, tumor budding, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, Crohn-like peritumoral reaction, proportion of tumor with mucinous histology, proportion of tumor with signet ring histology, presence and type of precursor lesion, and synchronous colorectal polyps. The grade of each colonic adenocarcinoma was scored using a 2-tiered scheme: low grade, with >50% gland formation, and high grade, with <50% gland formation. Tumor budding assessment was made using the rapid bud count method49: high budding, in which >50% of areas examined under 200x magnification were positive for budding, and low budding, in which <50% of areas examined under 200x magnification were positive for budding. The presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was defined as >7 lymphocytes per 10 high-power fields.38 Crohn-like peritumoral reaction was scored as absent, mild, or intense, as previously described.13 The presence or absence of precursor polyps and the histologic subtype of the precursor polyp associated with invasive colonic adenocarcinoma were recorded.15,39

Mismatch Repair Protein Immunohistochemical Analysis and MSI Analysis Polymerase Chain Reaction

Mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry was performed on a subset (n = 341, Stanford cases) of study cases using the standard streptavidin biotin peroxidase procedure. Primary monoclonal antibodies against MLH1 (clone G168–728, BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, 1:200), MSH2 (clone FE11, Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA, 1:100), MSH6 (clone 44, BD Transduction, San Jose, CA, 1:200), and PMS2 (clone MRQ-28, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, 1:10) were applied to 4-mm-thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohols to distilled water before undergoing antigen retrieval by heat treatment in either citrate solution pH 6.0 (MLH1, PMS2, and MSH2) or EDTA solution pH 9.0 (MSH6). An automated detection using a Leica Bond Autostainer (Buffalo Groove, IL) was carried out. Normal expression was defined as nuclear staining within tumor cells, using infiltrating lymphocytes as positive internal control. Negative protein expression was defined as complete absence of nuclear staining within tumor cells in the face of concurrent positive labeling in internal non-neoplastic tissues.

All Cleveland Clinic (386) and a subset of Stanford colonic adenocarcinomas were analyzed using the ProMega MSI analysis system using a panel of 5 mononucleotide microsatellite markers (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, and MONO-27) and 2 pentanucleotide repeats (Penta C and Penta D) incorporated into a multiplex fluorescence assay.43 Briefly, the tests were conducted on tumor and normal DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks using either the DNease Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or the DNAIQ Case-work Pro Kit (Promega, Madison, WI); manual microdissection was performed, when required, to exclude overabundance of nonlesional tissue. Paired DNA samples from neoplastic and non-neoplastic samples were genotyped and analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using either an ABI 310 or ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). In accordance with NCI guidelines, MSI at 2 loci or more was defined as MSI-high (MSI-H), instability at a single locus was defined as MSI-low (MSI-L), and no instability at any of the loci tested was defined as microsatellite stable (MSS).

BRAF and KRAS Mutation Analysis

DNA was extracted from paraffin sections, using either the DNease Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) (Stanford cases, n = 103) or the DNAIQ Casework Pro Kit (Promega) (Cleveland Clinic cases, n = 72) after xylene deparaffinization and ethanol wash. For all cases, BRAF mutation analysis at codon 600 (V600E) was performed by a real-time PCR based on an allelic discrimination method described previously.18,50 Briefly, real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using allele-specific primers designed to selectively amplify the wild-type (T1796) and mutant (A1796) BRAF alleles. The primer sequences were as follows: V, 5′-GTGATTTTGGTCTAGCTACtGT; E, 5′-CGCGGCCGGCCGCGGCGGTGATTTTGGTCTAGCTACcGA; and AS, 5′-TAGCCTCAATTCTTACCATCCAC. PCR amplification and melting curve analysis were performed on an iCycler iQ (Biorad, Hercules, CA) or Applied Biosystems 7500. Genomic DNA was amplified in a 25µmL volume containing 1X Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), forward primer V (300 nM), forward primer E (900 nM), and reverse primer AS (300 nM). The cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 2 minutes, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, and 60°C for 60 seconds. After amplification, samples were subjected to a temperature ramp from 60°C to 99°C, increasing by 1°C at each step. For wild-type samples, single peaks were observed at 80°C, whereas samples containing mutant alleles produced single peaks at 85°C.

For KRAS mutational analysis, 3 methods were utilized. For 103 Stanford cases, mutant KRAS was detected using a validated KRAS mutation kit (Entrogen, Tarzana, CA) that identifies the common somatic mutations located in codons 12, 13, and 61 of the KRAS gene. The mutations were detected on an Applied Biosytems 7900 (Applied Biosystems). Evaluation of KRAS assay results was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For 36 Cleveland Clinic cases, identification of point mutations in KRAS codons 12 and 13 was carried out using a Light Cycler 2.0 as described by Nikiforova et al.27 In brief, a PCR amplicon was generated using primers (K-rasF1: 5′AAGGCCTGCTGAAAATGACTG; K-rasR1: 5′ GGTCCTGCACCAGTAATATGCA) that flank the KRAS codon 12/13 mutational hotspot. Using a pair of fluorescently labeled anchor and sensor oligonucleotides (KRASanc1: 5′ CGTCCACAAAATGATTCT GAATTAGCTGTATCGTCAAGGC-AGT-fluorescein; KRASsnsr1: 5′ LC Red640-TGCCTACGCCACCAGCTCCAA-phosphate) that hybridize adjacent to each other, amplification and mutation detection was accomplished through fluorescence resonance energy transfer. The sensor oligonucleotide spans the mutation site, allowing for the detection of a codon 12 or codon 13 mutation based on the distinct melting temperatures (Tm) of wild-type KRAS and mutant KRAS. For the other 36 Cleveland Clinic cases, KRAS mutational analysis was performed by PCR amplification of a 263 base-pair product that included codons 12 and 13, followed by both forward and reverse cycle sequencing using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The following primers (Invitrogen/Gibco BRL) were used: KRAS Exon 1 forward primer = 5′-GGTGAGTTTGTATTAAAAGGTACTGG and reverse primer = 5′-TCCTGCACCAGTAATATGCA.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoints selected for analysis were disease-free survival and overall survival. Disease-free survival was defined as the time (measured in days) from date of initial diagnosis to the date of first evidence of tumor recurrence. Overall survival was defined as the time (measured in days) from the date of initial diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier methods with log-rank tests and with Cox regression methods. Univariate relationships between mutation status and continuous measures were assessed with 1-way ANOVA models, and associations between mutation status and categorical measures were assessed with the Fisher exact test or the Freedman-Halton extension of the Fisher exact test. All statistics were assessed using 2-sided tests with P-values <0.05 considered statistically significant. To help control for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni-adjusted P-values are also reported for the differences between mutation status in the log-rank test (KRAS vs. BRAF, BRAF vs. BRAF/KRAS wild type, and KRAS vs. BRAF/KRAS wild type). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic Features of Proximal Colon Adenocarcinomas Stratified by KRAS and BRAF Mutation Status

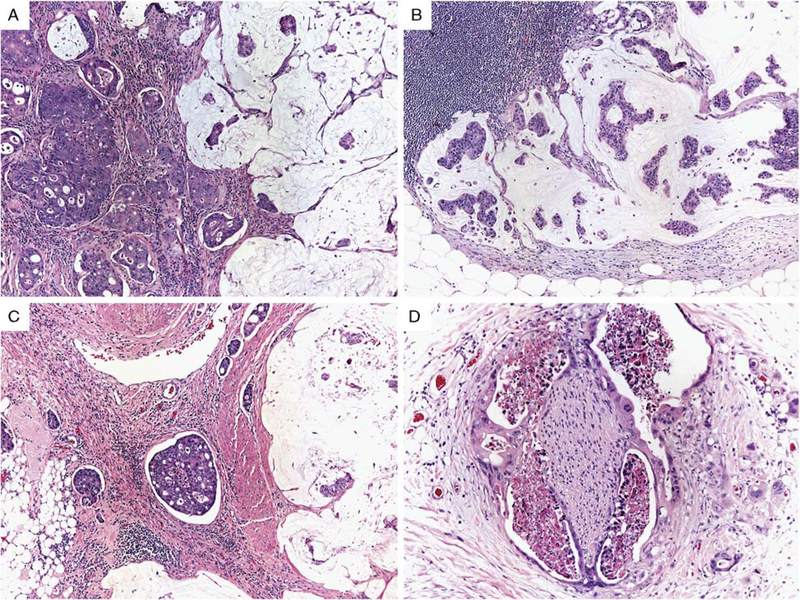

Of the 259 cases of proximal colonic adenocarcinoma analyzed for DNA mismatch repair abnormalities, 181 cases (70%), which constitute our study cases, were identified to be proficient in DNA mismatch repair using either MSI PCR (n = 78), mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry (n = 91), or both MSI PCR and mismatch repair immunohistochemistry (n = 12). The clinicopathologic features of the 181 study cases stratified by KRAS and BRAF mutation status are detailed in Table 1. For all cases, the mean age was 67 years (range, 33 to 98 y) with a similar age distribution between groups stratified by KRAS and BRAF mutation status (P = 0.20). BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas were seen more frequently in women (13/20, 65%) compared with KRAS-mutated adenocarcinomas (34/78, 44%) and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas (39/83, 47%), although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.23). BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas were more frequently stage III or IV (15/20, 75%) compared with KRAS-mutated adenocarcinomas (45/78, 57%) and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas (43/83, 52%); however, the difference in stage between these groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.45). As seen in Table 1 and Figure 1, there are clear differences among the rates of adverse histologic features between BRAF-mutated, KRAS-mutated, and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas, and differences among the three groups were driven by BRAF-mutated colonic adenocarcinoma. Compared with BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas, BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas more frequently demonstrated adverse histologic features such as lymphatic invasion (16/20, 80% vs. 75/161, 47%; P = 0.008), mean number of lymph node metastases (4.5 vs. 2.2; P = 0.01), perineural invasion (8/20, 40% vs. 13/161, 8%; P = 0.0004), and high tumor budding (16/20, 80% vs. 83/161, 52%; P = 0.02). BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas also demonstrated a distinct morphologic appearance compared with KRAS-mutated and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas (Fig. 1). BRAF-mutated adenocarci-nomas frequently contained areas with abundant extracellular mucin, which was either focal (<50% of tumor volume, 9 cases) or prominent (>50% of tumor volume, 6 cases). In addition, BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas frequently demonstrated signet ring histology (4/20, 20%), which was not seen as often in KRAS-mutated or KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas. In 3 of the 4 BRAF-mutated colon adenocarcinomas with a signet ring cell component in our series, the signet ring cells accounted for <10% of the tumor, with 1 case containing 50% of tumor cells with signet ring cell morphology. The associations of BRAF mutation and both mucinous histology and signet ring histol-ogy were statistically significant (P = 0.0002 and 0.03, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Clinical, Pathologic, and Molecular Features of Proximal Colonic Adenocarcinomas With Proficient DNA Mismatch Repair

| Clinical or Molecular Feature | All Cases | KRAS Mutation | BRAF Mutation | KRAS and BRAF Wild-type | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 181 | 78 | 20 | 83 | |

| Sex (%) | |||||

| Male | 96 (53) | 44 (56) | 7 (35) | 44 (53) | 0.23 |

| Female | 85 (47) | 34 (44) | 13 (65) | 39 (47) | |

| Mean age, years (range) | 67 (33–98) | 68 (35–95) | 71 (45–98) | 65 (33–85) | 0.20 |

| Tumor stage (%) | |||||

| I | 28 (15) | 13 (17) | 1 (5) | 14 (17) | 0.45 |

| II | 50 (28) | 20 (26) | 4 (20) | 26 (31) | |

| III | 69 (38) | 30 (38) | 8 (40) | 31 (37) | |

| IV | 34 (19) | 15 (19) | 7 (35) | 12 (15) | |

| Tumor grade (%) | |||||

| Low | 145 (80) | 65 (83) | 12 (60) | 68 (82) | 0.07 |

| High | 36 (20) | 13 (17) | 8 (40) | 15 (18) | |

| Lymphatic invasion (%) | 91 (50) | 41 (53) | 16 (80) | 34 (41) | 0.006 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 98 (54) | 43 (55) | 14 (70) | 41 (49) | 0.02 |

| Mean number of lymph node metastasis | 2.4 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 0.02 |

| Perineural invasion (%) | 21 (12) | 8 (10) | 8 (40) | 5 (6) | 0.0006 |

| Venous invasion (%) | 29 (16) | 12 (15) | 5 (25) | 12 (14) | 0.50 |

| Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (%) | |||||

| Absent | 166 (92) | 74 (95) | 18 (85) | 74 (97) | 0.18 |

| Present | 15 (8) | 4 (5) | 2 (10) | 9 (11) | |

| Crohn-like reaction (%) | |||||

| Absent | 107 (59) | 44 (56) | 9 (45) | 54 (65) | 0.29 |

| Mild | 49 (27) | 25 (32) | 7 (35) | 17 (20) | |

| Intense | 25 (14) | 9 (12) | 4 (20) | 12 (15) | |

| Tumor budding (%) | |||||

| Low | 82 (45) | 34 (44) | 4 (20) | 44 (53) | 0.02 |

| High | 99 (55) | 44 (56) | 16 (80) | 39 (47) | |

| Mucinous histology (%) | |||||

| Absent | 120 (66) | 53 (68) | 5 (25) | 62 (75) | 0.0002 |

| Present | 61 (34) | 25 (32) | 15 (75) | 21 (25) | |

| Focal (<50%) | 42 (23) | 19 (24) | 9 (45) | 14 (17) | |

| Prominent (>50%) | 19 (11) | 6 (8) | 6 (30) | 7 (8) | |

| Signet ring histology (%) | |||||

| Absent | 171 (94) | 75 (96) | 16 (80) | 80 (95) | 0.03 |

| Present | 10 (6) | 3 (4) | 4 (20) | 3 (5) | |

| Focal (<50%) | 8 (5) | 3 (4) | 3 (15) | 2 (4) | |

| Prominent (>50%) | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Precursor lesion (%) | |||||

| Adenomatous | 82 (45) | 39 (50) | 7 (35) | 36 (43) | 0.46 |

| Serrated | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | 0.21 |

| Synchronous polyp(s) (%) | |||||

| Adenomatous | 61 (34) | 29 (37) | 9 (45) | 23 (28) | 0.23 |

| Serrated | 12 (7) | 4 (5) | 4 (20) | 4 (5) | 0.06 |

FIGURE 1.

Microsatellite-stable proximal colonic adenocarcinomas with BRAF V600E mutation frequently demonstrated mucinous histology in both the primary tumor (A, ×100) and lymph node metastases (B, ×200), as well as lymphatic invasion (C, ×100), perineural invasion (D, ×200), and high tumor budding (D).

The histologic subtypes of the precursor polyp and any synchronous colorectal polyps, when identified, were also recorded for each colonic adenocarcinoma. The precursor polyps were most frequently adenomas in BRAF-mutated (3 tubular adenomas, 4 tubulovillous adenomas), KRAS-mutated (21 tubular adenomas, 17 tubulovillous adenomas, and 1 villous adenoma), and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas (23 tubular adenomas, 10 tubulovillous adenomas, and 3 villous adenomas). In contrast, there was an increased frequency of synchronous sessile serrated polyps (4/20, 20%) identified in BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas compared with KRAS-mutated (4/78, 5%) and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinoma (4/83, 5%), although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06).

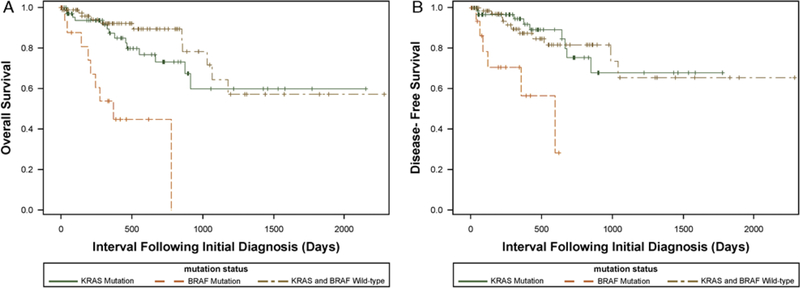

Clinical Outcome Stratified by KRAS and BRAF Mutation Status

Clinical follow-up data were available for 173 patients with a median follow-of 12 months (range, 0 to 76 mo) (Table 2). There was a statistically significant difference in survival between the 3 groups (P<0.0001) (Fig. 2). Although the precision of the survival estimates was limited by the small sample size of 20 BRAF-mutated colonic adenocarcinomas, patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas had a median survival of approximately 12 months, with 54% probability of living for 1 year and a 56% chance of surviving progression-free for 1 year. Interestingly, during the follow-up period of this study, most deaths and disease recurrences in patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas occurred within approximately 1 year of the patient’s initial surgical resection procedure, suggesting that BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas have a particularly aggressive early clinical course. All patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas were either dead or lost to follow-up at 2 years, except 1 patient who died at 25 months. Compared with patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas, patients with KRAS-mutated adenocarcinomas had sig-nificantly improved overall survival probability (1-year, Statistical analysis performed after adjusting for stage by grouping stages 1 to 2 and stages 3 to 4 tumors. 87% and 3-year, 60%; unadjusted log-rank P = 0.03 and Bonferroni-adjusted log-rank P = 0.08) and disease-free survival probability (1-year, 95% and 3-year, 68%; unadjusted log-rank P = 0.02 and Bonferroni-adjusted log-rank P = 0.05). Similarly, compared with patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas, patients with KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas had significantly improved overall survival (1-year, 92% and 3-year, 65%; unadjusted log-rank P = 0.0002 and Bonferroni-adjusted log-rank P = 0.0005) and disease-free survival (1-year, 87% and 3-year, 65%; unadjusted log-rank P = 0.02 and Bonferroni-adjusted log-rank P = 0.06). No significant difference in overall or disease-free survival was identified between patients with KRAS-mutated and KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas.

TABLE 2.

Proximal Colonic Adenocarcinomas With Proficient DNA Mismatch Repair: Long-term Follow-up According to BRAF and KRAS Mutation Status

| Mutation Status | Patients | Median Follow-up in Months (range) | NED | AWD | DOD | Overall Survival (%) |

Disease-free Survival (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 3 y | 1 y | 3 y | ||||||

| BRAF mutation | 19 | 8 (1–26) | 7 | 3 | 9 | 54 | * | 56 | * |

| KRAS mutation | 71 | 12 (1–72) | 52 | 7 | 12 | 87 | 60 | 95 | 68 |

| BRAF and KRAS wild-type | 83 | 12 (1–76) | 67 | 9 | 7 | 92 | 65 | 87 | 65 |

All patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas except 1 patient who died at 25 months were either dead or lost to follow up at 2 years.

AWD indicates alive with disease; DOD, dead of disease; NED, no evidence of disease.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing the overall survival of patients with proximal colon adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair harboring KRAS mutations, BRAF V600E mutation, or KRAS and BRAF wild type. Patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas had a significantly worse overall survival compared with KRAS-mutated (unadjusted log-rank P = 0.03) and KRAS/BRAF wild-type (unadjusted log-rank P = 0.0002) adenocarcinomas. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing the disease-free survival of patients with proximal colon adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair harboring KRAS mutations, BRAF V600E mutation, or KRAS and BRAF wild type. Patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas had a significantly worse disease survival compared with KRAS-mutated (unadjusted log-rank P = 0.02) and KRAS/BRAF wild-type (unadjusted log-rank P = 0.02) adenocarcinomas.

When adjusting for tumor stage (Table 3), survival analysis assessing KRAS and BRAF mutation status demonstrated that patients with BRAF-mutated adenocarcinoma had a significantly poor overall survival and disease-free survival (hazard ratio 6.63, 95% CI, 2.60–16.94; and hazard ratio 6.08, 95% CI, 2.11–17.56, respectively) compared with patients with KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas. In contrast, there was no difference in overall survival or disease-free survival be-tween patients with KRAS-mutated adenocarcinoma and those with KRAS/BRAF wild-type adenocarcinomas (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Stage-adjusted Survival Analysis of Proximal Colonic Adenocarcinomas With Proficient DNA Mismatch Repair Stratified by KRAS and BRAF Mutation Status

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Feature | Total | Overall Survival | Disease-free Survival |

| KRAS and BRAF wild-type | 83 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| KRAS mutation | 71 | 1.27 (0.58–2.81) | 0.88 (0.36–2.12) |

| BRAF mutation | 19 | 6.63 (2.60–16.94) | 6.08 (2.11–17.56) |

Statistical analysis performed after adjusting for stage by grouping stages 1 to 2 and stages 3 to 4 tumors.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that, in the proximal colon, BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair frequently demonstrate mucinous histology and are particularly aggressive with a significantly worse overall survival compared with BRAF wild-type and KRAS-mutated colon adenocarcinomas. The BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair identified in our study also display morphologic features typically associated with adverse behavior, including lymphatic invasion, perineural invasion, high tumor budding, and lymph node metastases.

Mucinous colonic adenocarcinoma is a frequently encountered histologic subtype of colorectal carcinoma, accounting for between 10% and 15% of colorectal cancer cases. There are many conflicting reports in the literature regarding the prognostic significance of mucinous colorectal carcinoma. In one of the earliest studies, Symonds and Viskery44 demonstrated a decreased overall survival for mucinous colorectal carcinoma compared with nonmucinous carcinoma, although the difference in survival was most striking for mucinous carcinomas of the rectum. In subsequent studies, mucinous carcinoma has been shown to be independently associated with decreased overall survival in some7,37,41 but not all stud-ies.6,11,14,21 Many of the studies evaluating the effect of mucinous differentiation on prognosis in colorectal carcinoma have failed to differentiate mucinous from signet ring cell carcinomas37,41; the latter are generally considered to be a more aggressive colorectal carcinoma subtype. In addition, most studies include in their analysis both proximal and distal colon and rectal carcinomas, which likely have distinctly different molecular characteristics. Assessing the importance of mucinous morphology and prognosis is made much more difficult given the close association of mucinous histology and MSI-H.45 MSI-H status is generally associated with improved overall and disease-free survival.31 Thus, the presence of MSI-H often confounds analysis of mucinous histology and survival in colorectal carcinoma. Of the few studies analyzing both MSI status and mucinous histology, MSI-H colorectal carcinomas had an improved survival compared with microsatellite-stable mucinous colorectal carcinomas,19,24 although the survival benefit was not independent of stage. Compared with these previous literature reports, we have taken several steps to eliminate the potential biases in this study that could have affected the outcome results. By restricting our analysis to colon adenocarcinomas demonstrating proficient DNA mismatch repair either by mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry or MSI PCR analysis, we eliminated the potential confounding effect of sporadic MSI-H colorectal carcinomas that frequently harbor BRAF mutations8,48 and that are generally associated with improved overall and disease-free survival.31 We also limited our analysis to proximal colon adenocarcinoma given previous literature reports identifying a higher proportion of BRAF-mutated colorectal adenocarcinomas in the proximal colon30,36 and the distinctly different pathways of carcinogenesis between the left and right colon.9,40 As such, we have removed the potential effects of tumor location and MSI on prognosis. The subset of BRAF-mutated proximal colonic adenocarcinoma with mucinous histology and dismal prognosis identified in our analysis may help to explain the poor survival of mucinous colon adenocarcinomas previously reported in some studies.

A number of studies have previously demonstrated the association of BRAF mutation and poor prognosis in microsatellite-stable colorectal carcinoma. Kakar et al20 analyzed 83 carcinomas from both the right and left co-lons and identified 10 cases that were microsatellite stable and harbored BRAF mutations (5 proximal and 5 distal). BRAF-mutated microsatellite-stable carcinomas had sig-nificantly worse 5-year survival, and BRAF mutation was found to be an independent predictor of poor survival in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer. Detailed morphologic features of BRAF-mutated microsatellitestable colorectal carcinomas were not specifically reported by Kakar et al.20 Samowitz et al36 studied 911 colorectal carcinomas and identified 40 (5%) BRAF-mutated microsatellite-stable colorectal carcinomas that had a significantly worse stage-adjusted overall survival. In addition, Samowitz and colleagues reported that 10/40 (25%) BRAF-mutated microsatellite-stable colorectal carcinomas demonstrated mucinous histology compared with 78/685 (10.2%) BRAF wild-type microsatellite-stable colorectal carcinoma, similar to our results. However, in this large population-based study by Samowitz and colleagues, mucinous histology was not clearly defined, and it appears that not all cases were histologically rereviewed for the study. Futhermore, in this study, other histologic characteristics were not rigorously analyzed, and detailed comparative analysis of BRAF-mutated and BRAF wild-type tumors was not stratified by location. In addition, in the Samowitz and colleagues’ cohort, proximal location was associated with decreased overall survival in their univariate analysis. As BRAF-mutated tumors in the study by Samowitz and colleagues were preferentially located in the proximal colon, location may have potentially biased their results. Finally, Ogino et al30 identified BRAF mutations in 52 of 528 (10%) microsatellite-stable colon carcinomas, many of which were located in the proximal colon. In contrast to Samowitz et al and Kakar et al, Ogino et al did not identify a difference in colon cancer-specific mortality between BRAF-mutated and BRAF wild-type microsatellite-stable colorectal carcinoma. However, in their analysis, Ogino et al found that BRAF mutation status when coupled with CIMP status stratified patients prognostically: BRAF-mutated CIMP-low/negative colon cancers had a significantly worse co-lon cancer-specific mortality compared with BRAF wild-type CIMP-low/negative colon cancers. Combined with our analysis, all these literature reports suggest that presence of BRAF mutation is a predictor of poor survival in colon adenocarcinoma. Our study is complementary to these prior studies and enhances previous data by performing a rigorous analysis of the histopathologic findings of the clinically aggressive BRAF-mutated, microsatellite-stable proximal colon adenocarcinoma.

In general, signet ring carcinoma has been shown to be independently associated with decreased overall survival.21,25,28,32,42 In our analysis, a small subset of BRAF-mutated proximal colon adenocarcinoma also demonstrated focal signet ring cell morphology. Ogino et al analyzed 32 colorectal carcinomas with a signet ring component, with 9 (28%) demonstrating BRAF mutations and 10 (26%) demonstrating KRAS mutations, indicating that mutations in the EGFR signaling pathway are not infrequent in signet ring colorectal carcinoma. However, in contrast to Ogino et al, in our series signet ring cell morphology was more often identified in BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas compared with KRAS-mutated tumors. A number of reasons may explain the discrepancy between our results and that of Ogino et al: (1) Ogino et al included carcinomas from the colon and rectum, whereas our analysis was restricted to proximal colon adenocarcinoma; (2) Ogino et al included tumors with high levels of MSI, whereas we restricted our analysis to microsatellite-stable carcinomas. Kakar et al studied 72 signet ring colorectal carcinomas, of which 39 were right sided, with most (81%) exhibiting MSI-H. Although Kakar et al did not identify a significant survival difference between MSI-H and microsatellite-stable signet ring cell carcinomas, stratification of these tumors based on BRAF mutation analysis and site of disease was not performed. Overall, our results indicate that among microsatellite-stable proximal colon adenocarcinomas, BRAF-mutated adenocarcinomas more often display signet ring morphology compared with KRAS/BRAF wild-type and KRAS-mutated adenocarcinomas.

In summary, BRAF-mutated proximal colon adenocarcinomas with proficient DNA mismatch repair have a dismal prognosis and an aggressive clinical course. In addition, these tumors often display mucinous differentiation, focal signet ring histology, and other adverse histologic features such as lymphatic and perineural invasion and high tumor budding. It is important that this subset of proximal colon adenocarcinoma be recognized clinically, as death and tumor recurrence typically occur early in the clinical course of the disease. Furthermore, as targeted therapies emerge for BRAF-mutated tumors, early recognition of this subset of colonic ad-enocarcinomas may become more essential to institute appropriate treatment.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1626–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. Kirsten ras mutations in patients with colorectal cancer: the “RASCAL II” study. Br J Cancer 2001;85:692–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V, et al. Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res 2008;68:8541–8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belly RT, Rosenblatt JD, Steinmann M, et al. Detection of mutated K12-ras in histologically negative lymph nodes as an indicator of poor prognosis in stage II colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2001;1:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos JL, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Prevalence of ras gene mutations in human colorectal cancers. Nature 1987;327:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connelly JH, Robey-Cafferty SS, Cleary KR. Mucinous carcinomas of the colon and rectum. An analysis of 62 stage B and C lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991;115:1022–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consorti F, Lorenzotti A, Midiri G, et al. Prognostic significance of mucinous carcinoma of colon and rectum: a prospective case-control study. J Surg Oncol 2000;73:70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng G, Bell I, Crawley S, et al. BRAF mutation is frequently present in sporadic colorectal cancer with methylated hMLH1, but not in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng G, Kakar S, Tanaka H, et al. Proximal and distal colorectal cancers show distinct gene-specific methylation profiles and clinical and molecular characteristics. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1290–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5705–5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enriquez JM, Diez M, Tobaruela E, et al. Clinical, histopatho-logical, cytogenetic and prognostic differences between mucinous and nonmucinous colorectal adenocarcinomas. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1998;90:563–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein SD, Sayegh R, Christensen S, et al. Genotypic classification of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Biologic behavior correlates with K-ras-2 mutation type. Cancer 1993;71:3827–3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham DM, Appelman HD. Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction and colorectal carcinoma: a potential histologic prognosticator. Mod Pathol 1990;3:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green JB, Timmcke AE, Mitchell WT, et al. Mucinous carcinoma— just another colon cancer? Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton SR, Bosman FT, Boffetta P, et al. Carcinoma of the Colon and Rectum Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hecht JR, Mitchell E, Chidiac T, et al. A randomized phase IIIB trial of chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and panitumumab compared with chemotherapy and bevacizumab alone for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, et al. Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1261–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jass JR, Baker K, Zlobec I, et al. Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: concept of a “fusion” pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology 2006;49:121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kakar S, Aksoy S, Burgart LJ, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the colon: correlation of loss of mismatch repair enzymes with clinicopathologic features and survival. Mod Pathol 2004;17: 696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakar S, Deng G, Sahai V, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics, CpG island methylator phenotype, and BRAF mutations in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancers without chromosomal insta-bility. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang H, O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, et al. A 10-year outcomes evaluation of mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1161–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1757–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim GP, Colangelo LH, Wieand HS, et al. Prognostic and predictive roles of high-degree microsatellite instability in colon cancer: a National Cancer Institute-National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Collaborative Study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messerini L, Ciantelli M, Baglioni S, et al. Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic mucinous colorectal cancers. Hum Pathol 1999;30:629–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizushima T, Nomura M, Fujii M, et al. Primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features and postoperative survival. Surg Today 2010;40:234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagasaka T, Koi M, Kloor M, et al. Mutations in both KRAS and BRAF may contribute to the methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1950–1960; e1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikiforova MN, Lynch RA, Biddinger PW, et al. RAS point mutations and PAX8-PPAR gamma rearrangement in thyroid tumors: evidence for distinct molecular pathways in thyroid follicular carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2318–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nissan A, Guillem JG, Paty PB, et al. Signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum: a matched control study. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1176–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogino S, Meyerhardt JA, Irahara N, et al. KRAS mutation in stage III colon cancer and clinical outcome following intergroup trial CALGB 89803. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:7322–7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut 2009;58:90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of micro-satellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Psathakis D, Schiedeck TH, Krug F, et al. Ordinary colorectal adenocarcinoma vs. primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: study matched for age, gender, grade, and stage. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1618–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 5931–5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60–00 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Schaffer D, et al. Relationship of Ki-ras mutations in colon cancers to tumor location, stage, and survival: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000;9:1193–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J, et al. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res 2005;65:6063–6069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secco GB, Fardelli R, Campora E, et al. Primary mucinous adenocarcinomas and signet-ring cell carcinomas of colon and rectum. Oncology 1994;51:30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smyrk TC, Watson P, Kaul K, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a marker for microsatellite instability in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2001;91:2417–2422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, et al. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al. , eds. WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:160–165. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugai T, Habano W, Jiao YF, et al. Analysis of molecular alterations in left- and right-sided colorectal carcinomas reveals distinct pathways of carcinogenesis: proposal for new molecular profile of colorectal carcinomas. J Mol Diagn 2006;8:193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suma KS, Nirmala V. Mucinous component in colorectal carcinoma—prognostic significance: a study in a south Indian population. J Surg Oncol 1992;51:60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung CO, Seo JW, Kim KM, et al. Clinical significance of signet-ring cells in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2008;21:1533–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suraweera N, Duval A, Reperant M, et al. Evaluation of tumor microsatellite instability using five quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats and pentaplex PCR. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1804–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Symonds DA, Vickery AL. Mucinous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer 1976;37:1891–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka H, Deng G, Matsuzaki K, et al. BRAF mutation, CpG island methylator phenotype and microsatellite instability occur more frequently and concordantly in mucinous than non-mucinous colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2006;118:2765–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaughn CP, Zobell SD, Furtado LV, et al. Frequency of KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2011;50:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med 1988;319:525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Cunningham JM, Winters JL, et al. BRAF mutations in colon cancer are not likely attributable to defective DNA mismatch repair. Cancer Res 2003;63:5209–5212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang LM, Kevans D, Mulcahy H, et al. Tumor budding is a strong and reproducible prognostic marker in T3N0 colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young J, Barker MA, Simms LA, et al. Evidence for BRAF mutation and variable levels of microsatellite instability in a syndrome of familial colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]