Abstract

The choriocapillaris is a unique vascular plexus located posterior to the retinal pigment epithelium. In recent years, there is an increasing interest in the examination of the interrelationship between the choriocapillaris and eye diseases. We used several techniques to study choroidal perfusion, including laser Doppler flowmetry, laser speckle flowgraphy, and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), but with the latter no standardized algorithm for quantitative analysis has been provided. We analyzed different algorithms to quantify flow voids in non-human primates that can be easily implemented into clinical research. In-vivo, high-resolution images of the non-human primate choriocapillaris were acquired with a swept-source OCTA (SS-OCTA) system with 100kHz A-scan/s rate, over regions of 3 × 3 mm2 and 12 × 12 mm2. The areas of non-perfusion, also called flow voids, were segmented with a structural, intensity adjusted, uneven illuminance-compensated algorithm and the new technique was compared to previously published methods. The new algorithm shows improved reproducibility and may have applications in a wide array of eye diseases including age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

1. Introduction

In recent years, there is an increasing interest to study and image the choroid that provides oxygen supply to the outer retina including the photoreceptors [1,2]. Imaging the choroid using optical imaging modalities is difficult, because of the anatomical location behind the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) that is highly scattering. Laser Doppler flowmetry [3] and laser speckle flowgraphy have been used to quantify microvascular flow [4], but measurements are limited to the fovea because the inner retina is avascular in this region. Laser speckle flowgraphy has also been used to study flow in larger choroidal vessels [5] and color Doppler imaging allows for the measurement of blood velocities in the posterior ciliary arteries that supply the choroid [6], but these approaches provide limited lateral resolution. More recently optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) [7–9] was introduced to image the choroid providing volumetric information on the microvasculature, but quantification is still challenging.

Swept-Source OCTA (SS-OCTA) has been used in a wide variety of recent studies as a non-invasive tool to visualize the choroid in-vivo [8–11]. Compared to spectral-domain OCTA, SS-OCTA offers several advantages including reduced fringe washout, lower sensitivity roll-off, increased imaging range with improved detection efficiency and dual balanced detection [12]. Commercial SS-OCT/OCTA systems for imaging the posterior pole of the eye operate at wavelengths around 1060 nm, which provides improved penetration over commercial spectral domain OCT/OCTA systems that operate at wavelengths around 850 nm [13]. The advantage of using SS-OCT/OCTA to investigate choroidal thickness has been well documented [14–16] and some commercial SS-OCT/OCTA systems have implemented automated choroidal segmentation. Enface choroid circulation analysis still remains challenging given the lack of distinct boundary between the choroidal layers, as well as low signal from choroidal vessels in OCT/OCTA scans, mainly due to the signal loss of the light penetrating through the RPE [17].

The choriocapillaris is the anterior-most choroidal layer underneath the RPE. This is a thin, monolayer vascular network that provides metabolic supply to the photoreceptors, carries out waste from the RPE, and regulates the temperature of the posterior retina [1]. The geometry of the choriocapillaris perfusion map is non-homogenous and several histological studies [18–21] have shown the decrease of vascular perfusion from the posterior pole to the periphery. In OCTA images, unlike choroidal vessels, choriocapillaris is seen as bright pixels, while the non-perfused areas are shown as dark regions, and referred to as flow voids. The sizes and patterns of flow voids can be altered by age-related macular degeneration [22–24], myopia [25], and hypertension [26]. However, the knowledge of how to optimally use OCTA to evaluate choriocapillaris remains very limited. Different algorithms have been developed to quantify the flow voids, but the comparison between these approaches is lacking. There is a disagreement in terms of the density of flow void in normal human eyes from various studies using OCTA [26–29], which may be related to different segmentation methods, different instruments used, the compensation mechanisms for projection artifacts from the superficial blood vessels, and the different thresholding algorithms. In addition, most of the studies focused on a relatively small region centered at the fovea, and have not provided an insight to more peripheral regions of the choriocapillaris.

In the present study, we used SS-OCTA derived choriocapillaris images from non-human primates to evaluate and compare different algorithms. So far, to the best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted to image the choriocapillaris in non-human primates using OCTA. The rationale behind this approach was two-fold. On the one hand, the similarity of ocular vascular network to human, the presence of a macula and cone photoreceptor predominance [30] make the non-human primates an attractive animal model to investigate the role of the choroid in AMD-like pathology. Importantly, many studies have reported signs of AMD in older non-human primates and some studies also observed early onset drusen [31]. On the other hand, the images are less influenced by motion artifacts, which can affect quantification of flow voids. Motion-related artifacts make comparison of different algorithms difficult, because limited reproducibility can either be a result of poor image quality or of poor algorithm performance.

Two different protocols (3 × 3 mm2 and 12 × 12 mm2) were used and a new algorithm was developed to analyze the choriocapillaris plexus. This algorithm accounts for the dark appearance of deeper choroidal vessels and the uneven illuminance that is particularly important when wider fields are used.

2. Methods

2.1 Animal preparation

The experimental study included eight adult cynomolgus macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) with a mean age of 5.5 ± 1.2 years (range 4.5 - 6.8 years) and a mean weight of 4.8 ± 1.1 kg (range 3.8 - 6.0 kg) with ages ranging from 4 to 10 years. All animal procedures conformed to the adherence to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the SingHealth standard for responsible use of animals in research, from whom ethical approval was obtained (approval number 2017/SHS/1331). All the procedures were carried out in the SingHealth Experimental Medicine Centre, which is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC).

All the animals used in this study were socially housed in groups of between 3 and 5. Animals were in cage measuring 1.22m L × 1.83m D × 1.83m HT. Cages were made of stainless steel. The temperature of the housing room was maintained at 25–27°C and the relative humidity was 45~55%. Regular changes of equipment and toys were provided. Foods were provided two times a day and water was available ad libitum. Before recruiting into the experiment, all cynomolgus monkeys were given comprehensive ocular examination, including anterior segment and fundus examination, to exclude any ocular disease. Cynomolgus monkeys were not sacrificed in order to be followed up for a long-term observation.

2.2 System setup and imaging protocols

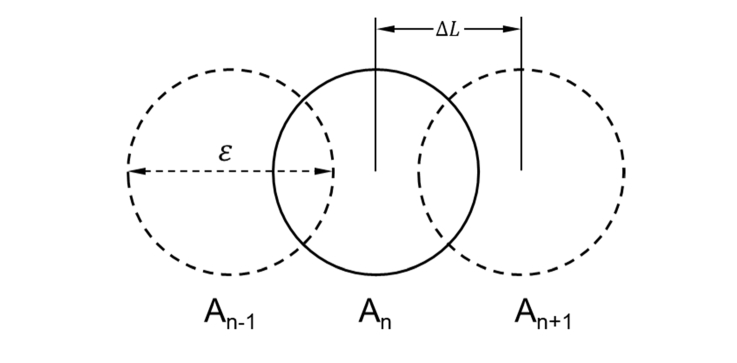

OCTA images were acquired by a commercial SS-OCT system (PLEX Elite, Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, California, USA). Briefly, the system operates at 1040 −1060 nm central wavelength, 100 nm bandwidth, and 100kHz A-scan rate. Axial resolution in tissue is 6.3 μm and lateral resolution is 20 μm. The system is integrated with an eye tracker and a line-scanning ophthalmoscope (λ = 750 nm) to achieve motion compensated wide field images. Each monkey was scanned by two different imaging protocols: 3 × 3 mm2 centered at the fovea and 12 × 12 mm2 wide filed including optic nerve head, macula and peripheral regions. In each image volume, a total number of 300/500 B-scans were sampled in the vertical direction, and each B-scan has 300/500 A-scans, sampled in the horizontal direction, corresponding to a sampling rate of 2 in 3 × 3 mm2 protocol, and a slight under-sampling in the 12 × 12 mm2 protocol. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic of image sampling by point scan mode. An-1, An and An + 1 refer to three adjacent OCT A-scans. If the lateral resolution of the system is ε, and the lateral shift between two adjacent A-scans is ∆L, then the sampling rate is defined as ε/∆L.

Fig. 1.

The schematic of imaging sampling by point scan mode. An-1, An and An + 1 refer to three adjacent A-scans. ε is the lateral resolution of the system. ∆L is the lateral shift between adjacent A-scans. The sampling rate is defined as ε/∆L.

An optical microangiography protocol that utilizes both intensity and phase signal was applied to generate depth-resolved OCTA signal [32,33]. In a subgroup (N = 3) of monkeys, a repeatability test was conducted where each imaging protocol was repeated three times with 3-minute acquisition interval. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated and reported. Repositioning of the monkey eye was performed through live fundus display between volume acquisition cycles to ensure the proper alignment of the imaging beam.

2.3 Image processing

The RPE layer was automatically segmented by a built-in segmentation tool from the review software (PLEX Elite 9000 Angiography Analysis, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA), and manual correction was performed when necessary. The choriocapillaris was then segmented within a thin slab (31-40 µm) below the RPE, and a maximum projection in the axial direction was performed to extract the enface choriocapillaris map. Both angiographic and morphological enface images were exported from the review software and transferred to MATLAB for further analysis (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Indeed, the choriocapillaris was found to be thinner than 10 µm in histology [20], but usually it is more a question whether it is practical to reliably segment such a thin slab from a commercial system. A summary of the thicknesses of choriocapillaris slab segmentations from other groups is shown in Table 1, and 10 µm thin slab segmentation used here is lower than the average.

Table 1. A summary of thicknesses of choriocapillaris segmentations from previous studies.

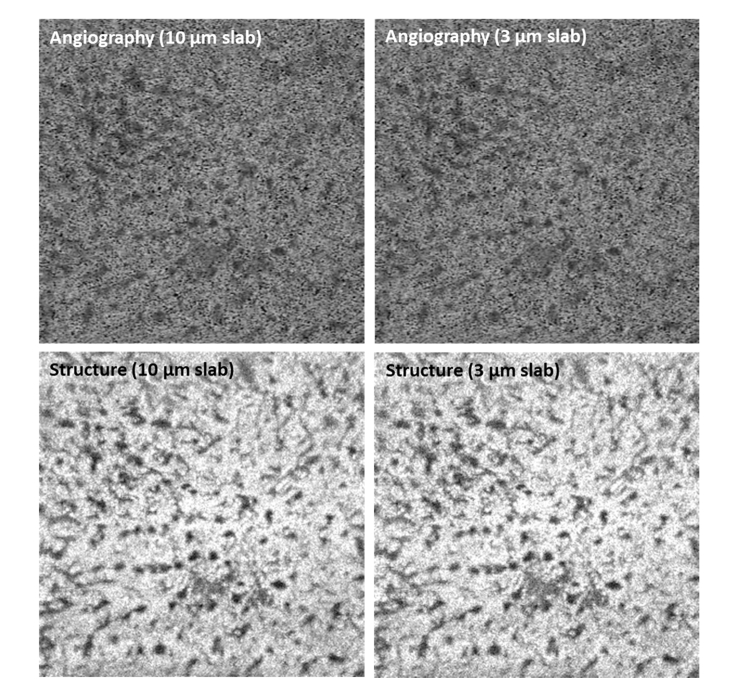

Moreover, the axial resolution of the current system is 6.3 µm in tissue, and the axial digital sampling is 1.95 µm/pixel. Hence taking a thinner slab is only cutting into the interpolated values and will not affect the appearance of large choroidal vessels from deeper layers. Figure 2 shows an example of taking 10 µm and 3 µm thin slabs starting from 31 µm underneath the RPE. It is noted that the angiographic and structural images from two segmentations are similar.

Fig. 2.

Angiographic and structural enface choriocapillaris images max projected from 10 µm slab and 3 µm slab.

The vascular network of choriocapillaris is densely packed and complicated; therefore, the analysis is usually performed based on the non-perfused regions, also known as flow voids. Anatomically there is no clear separation between the choriocapillaris and their feeding arterioles and draining venules. Therefore, the appearance of the choroid in the choriocapillaris slab limits the accurate segmentation of flow voids.

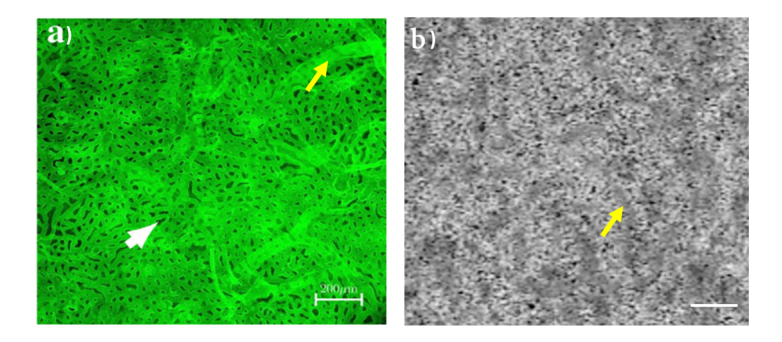

Figure 3(a) shows a previously published choriocapillaris image at the posterior pole of a human donor eye, imaged by high resolution confocal microscopy (using a Zeiss 710 LSM microscope, Zeiss, Germany) [21]. The image was taken from the anterior side. Figure 3(b) shows an image of the choriocapillaris from a non-human primate eye as obtained from a 3 × 3 mm2 area centered at the fovea in our study. For better comparison, the OCTA image was cropped to the same size as Fig. 3(a). The yellow arrows indicate the appearance of larger choroidal vessels using both optical imaging modalities, and the white arrow indicates a flow void.

Fig. 3.

a) an image of choriocapillaris taken from the retina side at the posterior pole of a human donor eye using a high resolution confocal microscopy. The image was modified from [21]. b) an uncompensated image of choriocapillaris taken at the fovea of a non-human primate eye. The image was cropped to the same size as a) from a 3 × 3 mm2 image. Yellow arrows indicate the appearance of deeper choroidal vessels using both methods. White arrow indicates a flow void. Scale bar: 200 µm.

To address the problem of large vessel appearance, we propose a simple approach to identify the flow voids by adjusting the low SNR regions in the image, namely:

| (1) |

Iadjusted, IOCTA and IMorph denote the adjusted, angiographic and morphological images, respectively. The power coefficient n is to adjust the SNR difference between the angiographic and morphological images. Hence, n is computed as to achieve the minimum variance of the adjusted image, namely:

| (2) |

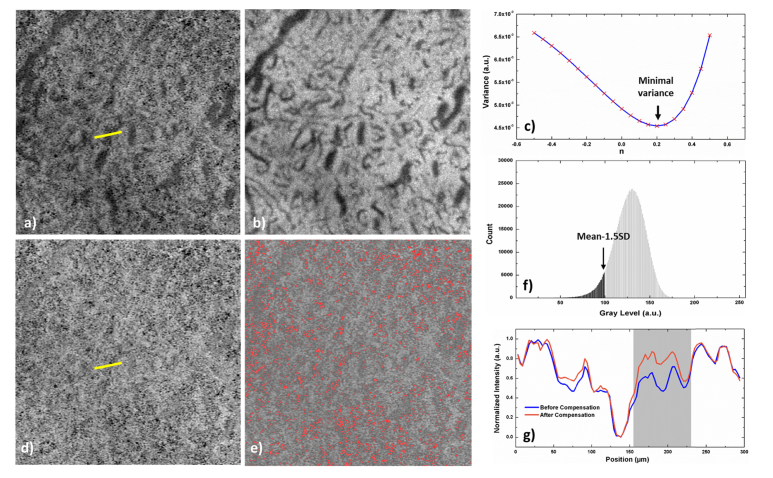

is the mean intensity of the adjusted image, and N represents the total number of pixels in the image (1024 × 1024 pixels). Figure 4(a-b) show the angiographic and morphological images covering a 3 × 3 mm2 macular area. It is obvious that the medium size choroidal vessels appear as low intensity regions on both types of images, yet with different contrast levels. Figure 4(c) shows the relation between the intensity variance of the adjusted image and the power coefficient n, where the global minimum variance is reached when n = 0.2. Figure 4(d-e) show the adjusted choriocapillaris image and the flow void segmentation as marked in red, respectively. Flow voids are thresholded at , where is the standard deviation of the adjusted image. Pixels are considered as flow voids when their values are below the threshold level. Figure 4(f) represents the grayscale histogram of the image presented in Fig. 4(d). Gray and black colors represent the flow voids and choriocapillaris, respectively, and the arrow marks the threshold level. The intensity profiles of the yellow lines in uncompensated and compensated choriocapillaris images are plotted in Fig. 4(g). While the overall contrast is not changed, the low intensity region affected by the deeper choroidal vessels is compensated (gray region in the plot). This proposed flow void segmentation method was compared with other previously published methods, and the flow void densities and ICCs from the repeatability test are reported.

Fig. 4.

Illustration of flow void segmentation method. (a-b) Angiographic and structural enface images of the choriocapillaris. (c) The variance of the adjusted image reaches its minimum when n equal to 0.2 in this particular image. (d) The adjusted choriocapillaris image where the dark region from the deep choroidal vessels is compensated. (e) The choriocapillaris with flow voids labeled in red while the threshold level is set to be from the grayscale histogram of the image (f). The intensity profiles of the yellow lines in uncompensated (a) and compensated (d) choriocapillaris images are plotted in (g). The low intensity region affected by the deep choroidal vessels is compensated (gray region in the plot), while the overall contrast is not changed.

Two imaging protocols (3 × 3 mm2 and 12 × 12 mm2) were used in the present study consisting of 300 and 500 A-scans and B-scans, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. The Choriocapillaris Imaging Protocols.

| Imaging Area | No. of A-scan | No. of B-scan | No. of repeated B-scans | Sampling rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 mm2 | 300 | 300 | 4 | 2 | ||

| 12 × 12 mm2 | 500 | 500 | 2 | 0.8 | ||

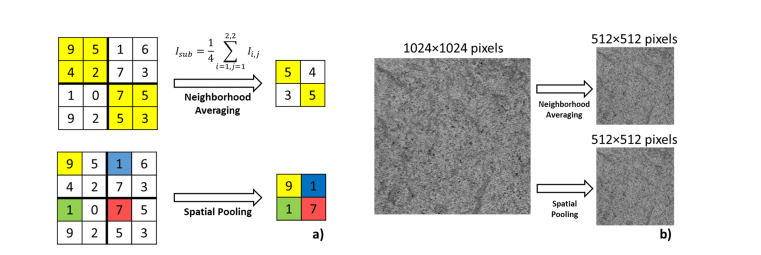

Hence, different sampling rates in two image protocols could potentially affect the segmentation accuracy of flow voids. In order to investigate this issue, we artificially decrease the pixel resolution from 3 µm to 30 µm of the 3 × 3 mm2 through two approaches: 1. Neighborhood averaging and 2. Spatial pooling. At each pixel resolution step, the flow void size and density were computed. The demonstration of these two methods to convert a 4 × 4 grid to a 2 × 2 grid is shown in Fig. 5(a). With neighborhood averaging method, each element of the 2 × 2 grid represents an average of the corresponding 2 × 2 block from the original grid, while with the spatial pooling method, each element of the 2 × 2 grid is always first element of the corresponding 2 × 2 block from the original grid. The sample choriocapillaris images (1024 × 1024 pixels) downsampled to 512 × 512 pixels by both methods are shown in Fig. 5(b).

Fig. 5.

Illustration of two different downsampling methods. (a) The concept demonstration to convert a 4 × 4 grid to a 2 × 2 grid. (b) A sample choriocapillaris image downsampled by a factor of 2 with both methods.

Except from the low pixel resolution, wide field imaging suffers from uneven illuminance. In other words, the illuminance level is higher at the central area than the peripheral area. Therefore, moving window segmentation was applied (window size 3 × 3 mm2, step size 1 mm), while in each window the flow voids were segmented by a threshold level of mean – 1.5 × SD. For demonstrating the flow void distribution on a large scale, eleven eyes were imaged with wide-field imaging protocol, and all the images were aligned based on the location of the fovea and the orientation from the center of the optic disk to the fovea. The optic disk was excluded manually during the procedure and the method to compute its distribution is similar to the retinal vessel density calculation reported previously [39]. All means in this paper are reported with the SD unless otherwise noted.

3. Results and discussions

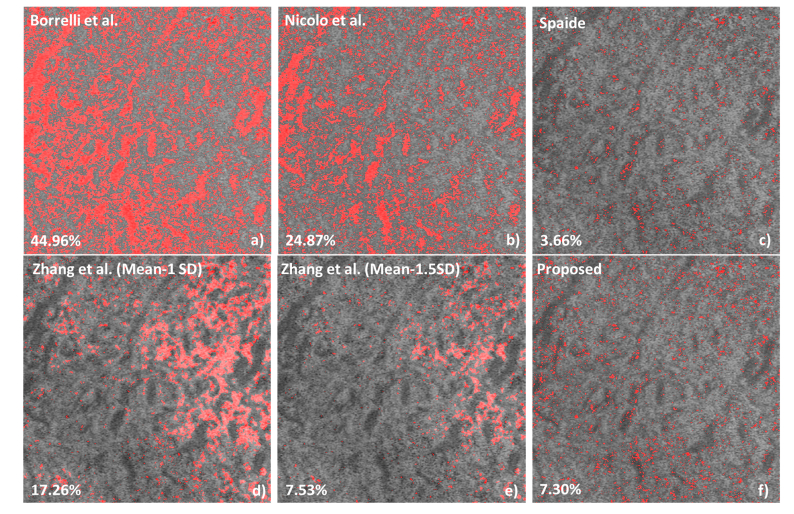

In total of 16 non-human primate eyes were imaged, and images from 11 eyes with sufficient quality were selected for further analysis. Figure 6 shows an example comparing the flow void segmentation results as proposed by other investigators and the technique developed by us. The density results are shown at the bottom left hand side. Figure 6(a) used a static method [34], where the threshold levels were set as the mean values of avascular outer retinal layer. This method was applied on SD-OCT images acquired from an 840 nm central wavelength system. However, this method has the following limitations: 1. this method is sensitive to the accuracy of avascular layer segmentation; 2. the superficial blood vessels project shadows onto this avascular layer resulting in an increase of the mean value. Similar static threshold methods were also applied by other researchers [35,40]. Figure 6(b) used Otsu’s method [41] which automatically decides the threshold level based on image grayscale histogram [23]. Again, Otsu’s method assumes two distinctive peaks in the image histogram to represent the background and foreground, which is not suitable for our choriocapillaris images as the grayscale histograms expressed a single peak. Figure 6(c-e) implemented dynamic methods by considering the local intensity variation. Figure 6(c) used Phansalkar locally adaptive threshold [26], where the circular local window radius was set to 45 μm here. In a more recent study, Zhang et al. [29] compensated the choriocapillaris angiogram based on their morphological images, and then the flow voids were segmented by mean-SD and mean-1.5 × SD, as shown in Fig. 6(d-e), respectively. This method may over-compensate the low intensity regions in the angiogram and miss the flow voids within these areas. The proposed method, on the other hand, compensates the angiographic image from the corresponding structural image, where the low intensity from deeper choroidal vessels is dampened but not over-compensated. These methods were applied to all studied eyes and the statistical results are shown in Table 3. The P values reported here are the probability that you would have found the current result if the correlation coefficient were zero (null hypothesis), and the correlation coefficient is considered statistically significant if P<0.05 [42].

Fig. 6.

The demonstration of applying different flow void segmentation algorithms on a 3 × 3 mm2 choriocapillaris image centered at the fovea. (a) Borrelli et al. [34] used the global threshold method where the threshold level was set to be the mean intensity of the avascular outer retinal layer. (b) Nicolo et al. [24] applied Otsu’s thresholding method. (c) Spaide [26]. used Phansalkar local threshold method. (d-e) Zhang et al. [29] used the structural image to compensate the angiogram, and then used mean-1SD and mean-1.5SD to binaries the compensated images.

Table 3. Statistical results of flow void density on a 3 × 3 mm2 area centered at the fovea using different segment methods. For calculating the flow void density from all studied eyes (N = 11) were analyzed. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated from three repeated measurements in three animals.

| Methods | Flow void density (%) | ICC(95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borrelli et al. [24] | 34.11 ± 18.07 | 0.570 (0.061, 0.914) | 0.018 |

| Nicolo et al. [34] | 45.55 ± 1.77 | 0.904 (0.674, 0.985) | <0.001 |

| Spaide [26] | 6.96 ± 4.18 | 0.850 (0.543, 0.975) | <0.001 |

| Zhang et al. (mean-1SD) [29] | 17.2 ± 0.32 | 0.715 (0.289, 0.947) | 0.001 |

| Zhang et al. (mean-1.5SD) [29] | 7.33 ± 0.71 | 0.622 (0.116, 0.928) | 0.011 |

| Proposed | 8.47 ± 1.37 | 0.950 (0.806, 0.992) | <0.001 |

Figure 6 and Table 3 show that there is a large difference between the different algorithms proposed for flow void segmentation and absolute values vary more than 7-fold. Figure 6 also indicates that the different algorithms show considerable local variation in segmenting flow voids. Obviously, the algorithm provided by Spaide [26] is the one that matches best the technique proposed in this paper. The data in Table 3 also show that there is a wide variety in animal to animal differences between algorithms. Whereas with the algorithm of Nicolo et al. [34] the SD is less than 4% of the mean it is as high as 60% for the algorithm by Spaide [26]. Also, the ICCs vary significantly between the different algorithms. According to the criteria by Koo and Li [43], only two algorithms provide excellent reproducibility (defined > 0.9) with the present algorithm showing the least variability. The algorithm by Spaide [26] provides good reproducibility, whereas the other three algorithms provide moderate reproducibility. Our results clearly indicate that different algorithms for segmenting flow voids have different performance and data are not comparable between different algorithms. Also, the different algorithms may largely differ in discriminating health from disease, but further data are required to better understand the diagnostic performance in different pathologies. It is also noted that because of limited sample size, the improvement of reproducibility using the proposed method is only close to significant compared to Borrelli’s approach (P = 0.07).

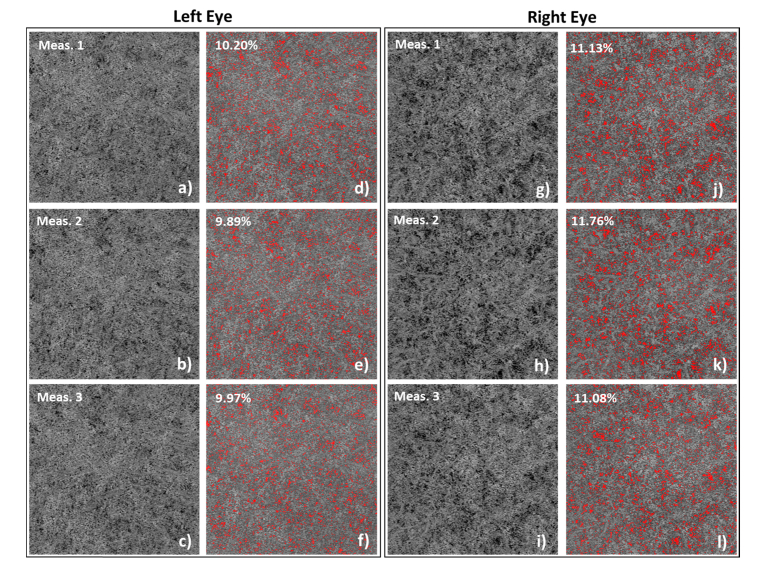

Figure 7 represents an example of three consecutive choriocapillaris recordings from both eyes of one non-human primate, with inter-eye differences due to an unknown reason. The data are evaluated using our newly developed algorithm. Slight misalignment among images was probably caused by the head movement. It is obvious that the distribution and the calculated densities of flow voids in both eyes are consistent. Especially, the inter-eye flow void density difference is on average 1.3%, which is much larger than the SD of the flow void densities from repeated scans of the left eye (0.16%) and right eye (0.37%), respectively.

Fig. 7.

Repeated measurements from both eyes of a non-human primate. Inter-eye differences in choriocapillaris due to an unknown reason are noticed. The adjusted choriocapillaris images are shown in a-c) and g-i), and the images with choriocapillaris with flow voids segmented are shown in d-f) and j-l).

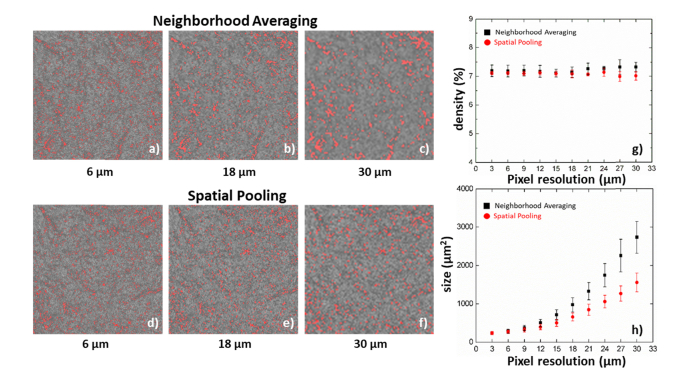

The effect of pixel resolution on the characteristics of flow voids is summarized in Fig. 8. The images exported from the review software have been interpolated from 300 × 300 pixels to 1024 × 1024 pixels, which artificially increased the sampling rate from 2 to 6.8. The exported image was downsampled by factors of 2, 6 and 10 using neighborhood averaging (Fig. 8(a-c)) and spatial pooling (Fig. 8(d-f)) methods, which correspond to pixel resolutions of 7 μm, 18 μm and 30 μm, respectively. The figures were then rescaled to the same size for better visual comparison. Neighborhood averaging is methodologically similar to applying a spatial filter or having lower optical transverse resolution, and reduces the sampling rate from 6.8 to 1.9. It is obvious that reducing the pixel resolution results in merging of adjacent flow voids and loss of small flow void visualization. Conversely, spatial pooling mimics a sparse scanning pattern and progressively reduces the sampling rates from 6.8 to undersampling, similar to a reduced number of A-scans and B-scans over the same imaging area. Figures 8(g-h) summarize the statistical results of flow void density and size with the two downsampling approaches. Spatial pooling can better preserve the flow void distribution and there is no significant alteration in flow void density with a change in pixel resolution. However, both methods artificially increase the size of the flow voids and this change is more pronounced with neighborhood averaging. Therefore, it is important to understand that the direct comparison of flow void sizes between different scanning densities needs to be done with caution. Even if the same 3 × 3 mm2 scanning area is imaged results will depend on the sampling rate as well as the number of A-scans and B-scans.

Fig. 8.

A 3 × 3 mm2 choriocapillaris image centered at the fovea downsampled by factors of 2, 6 and 10 using both neighborhood averaging (a-c) and spatial pooling (d-f) methods, which correspond to the pixel resolutions of 6 μm, 18 μm and 30 μm, respectively. Over an increase of the pixel resolution, the flow void density maintains at a relatively consistent level (g), and flow void sizes increase progressive using both methods.

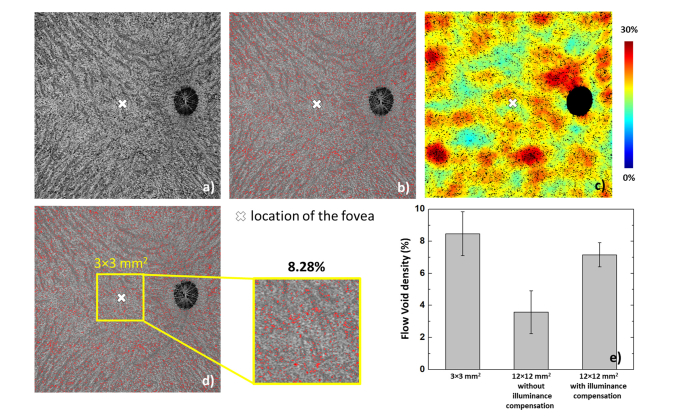

The choriocapillaris flow voids on a 12 × 12 mm2 region are shown in Fig. 9. As stated above, except flow void size, no significant changes of flow void characteristics, including density and distribution, should be expected from the sparse scanning pattern. It is also noted that the time interval between repeated B-scans could potentially affect the decorrelation signal. However, in both protocols, the time intervals are larger than 4 ms indicating that the computed decorrelation signal is close to saturation [44]. Therefore, the difference of variable time intervals can be ignored with the present scanning patterns. Figure 9(a) is an original choriocapillaris image, and 9(b) illustrates the overlaid segmented flow voids (red) on the choriocapillaris angiogram. A flow void distribution map is shown in Fig. 9(c) with jet color scheme, where the segmented flow voids were converted to black for better visualization. In this particular animal, the flow void density at the central cropped 3 × 3 mm2 area is 8.28% (Fig. 9(d), whereas the flow void density from the 3 × 3 mm2 protocol is 7.48% (figure not shown). Figure 9(e) shows the comparison of flow void density in the same 3 × 3 mm2 area, acquired from three different approaches (densely sampled 3 × 3 mm2 protocol; cropped from 12 × 12 mm2 with/without illuminance compensation). If the uneven illuminance is not compensated, the density of the flow voids is significantly underestimated compared to the 3 × 3 mm2 protocol (3.56 ± 1.34% vs. 8.47 ± 1.37%, P < 0.001, paired t-test). Conversely, moving window thresholding scheme can compensate the uneven illuminance and the results show better agreement with those from the densely sampled, 3 × 3 mm2 protocol (7.14 ± 0.65% vs. 8.47 ± 1.37%, P = 0.026, paired t-test).

Fig. 9.

(a) The original choriocapillaris image. (b) the choriocapillaris image overlaid with the segmented flow voids (red). (c) The flow void density distribution map generated from (b), while the flow voids were shown in black color for better visualization. (d) A 3 × 3 mm2 area cropped around the fovea from the wide field image, and the flow void density within is 8.28%, where for the same region, the corresponding flow void density from a densely sampled 3 × 3 mm2 protocol is 7.48%. (e) Statistical comparison of the same 3 × 3 mm2 area acquired from acquired by 3 × 3 mm2 protocol, 12 × 12 mm2 without uneven illuminance and 12 × 12 mm2 with uneven illuminance compensation. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

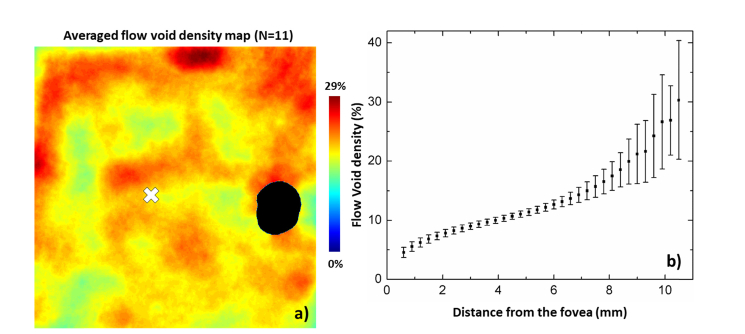

Figure 10 demonstrates the averaged wide field flow void distribution from eleven eyes. Figure 10(a) shows the averaged flow void density map and Fig. 10(b) delineates the change of flow void density with regard to the distance to the fovea. In general, flow void density around the peripapillary region is higher at the superior and inferior quadrants compared to nasal and temporal quadrants. Again, the density is lower around the fovea compared to the peripheral retina, and increases non-linearly towards the periphery. Quantitatively, the flow void density increases monotonically from the fovea to the periphery: the density is ~6-8% near the fovea and reaches ~27% at a distance of ~10 mm from the fovea.

Fig. 10.

Wide field flow void distribution from eleven eyes (N = 11). (a) The averaged flow void density map. (b) Flow void density at different distances to the fovea. ONH was excluded manually in the density calculation.

The increased density of flow voids is in line with several histology studies and findings from fluorescence angiography [18–21]. For instance, McLeod et al. [19] described the choriocapillaris network as a dense honeycomb shape structure at the posterior pole, whereas the periphery network is fanlike with less dense perfusion. This distribution pattern was proposed to provide good metabolic supply to the photoreceptors that reduce in density towards the periphery [45]. More recently, several studies [20,22,24,25] have suggested that alterations in flow void distribution may be linked to ocular pathologies such as AMD. To date, the hypothesis that increased flow void density is associated with progression of AMD remains unproven, although one study showed an association between choriocapillaris non-perfusion and poor visual acuity in eyes with reticular pseudodrusen [22]. The hypothesis is, however, supported by two studies using laser Doppler flowmetry showing that low subfoveal choroidal blood flow is a risk factor for the development of choroidal neovascularization [46,47].

The flow void analysis on wide-field OCTA here may provide an optimal approach that can also be employed in futures clinical studies. The present paper focused on non-human primates and allowed to understand some basic features of flow void segmentation including lateral resolution, sampling rate, thresholding and illuminance. After all, challenges from human data need to be addressed in the future. The current quantification approach didn’t take into consideration other artifacts such as superficial vessel projection and the shadows arising from drusen. However, previous studies have proven that such artifacts can be removed by excluding regions of superficial vessels and compensating the signal from underneath the drusen [29]. Other challenges are related to motion artifacts. Obviously, the artifacts may lead to incorrect segmentation of the flow voids. Such issues may for instance be simulated by artificially introducing motion to the imaged objects, which we plan to do in the near future.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we reported the visualization and quantification of choriocapillaris flow voids in healthy non-human primate eyes, using novel image compensation and flow void segmentation methods. OCTA provides in-vivo, non-invasive platform of studying wide field choriocapillaris characteristics in non-human primates. As compared to previously published algorithms the reproducibility is largely improved. In keeping with histological data, we observed an increased density of flow voids towards the peripheral retina. The current algorithm can be applied to wide-field OCTA images obtained from patients with ocular diseases with choroidal microvasculature abnormalities. Due to the high reproducibility improved diagnostic performance may be expected, but this needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Acknowledgments

The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Funding

National Medical Research Council (NMRC/CG/C010A/2017, OFIRG/0048/2017, NMRC/TA/0026/2014); A*STAR (BMRC-AStar MedTech, 1619077002) Singapore.

Disclosures

Gerd Klose is employed by Carl Zeiss Meditec. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Schmetterer L., Kiel J. W., Ocular Blood Flow (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linsenmeier R. A., Zhang H. F., “Retinal oxygen: from animals to humans,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 58, 115–151 (2017). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riva C. E., Cranstoun S. D., Grunwald J. E., Petrig B. L., “Choroidal blood flow in the foveal region of the human ocular fundus,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35(13), 4273–4281 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugiyama T., Araie M., Riva C. E., Schmetterer L., Orgul S., “Use of laser speckle flowgraphy in ocular blood flow research,” Acta Ophthalmol. 88(7), 723–729 (2010). 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calzetti G., Fondi K., Bata A. M., Luft N., Wozniak P. A., Witkowska K. J., Bolz M., Popa-Cherecheanu A., Werkmeister R. M., Schmidl D., Garhöfer G., Schmetterer L., “Assessment of choroidal blood flow using laser speckle flowgraphy,” Br. J. Ophthalmol. 102(12), 1679–1683 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stalmans I., Vandewalle E., Anderson D. R., Costa V. P., Frenkel R. E. P., Garhofer G., Grunwald J., Gugleta K., Harris A., Hudson C., Januleviciene I., Kagemann L., Kergoat H., Lovasik J. V., Lanzl I., Martinez A., Nguyen Q. D., Plange N., Reitsamer H. A., Sehi M., Siesky B., Zeitz O., Orgül S., Schmetterer L., “Use of colour Doppler imaging in ocular blood flow research,” Acta Ophthalmol. 89(8), e609–e630 (2011). 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitgeb R. A., Werkmeister R. M., Blatter C., Schmetterer L., “Doppler optical coherence tomography,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 41, 26–43 (2014). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C.-L., Wang R. K., “Optical coherence tomography based angiography [Invited],” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(2), 1056–1082 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.001056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashani A. H., Chen C.-L., Gahm J. K., Zheng F., Richter G. M., Rosenfeld P. J., Shi Y., Wang R. K., “Optical coherence tomography angiography: A comprehensive review of current methods and clinical applications,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 60, 66–100 (2017). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan A. C. S., Tan G. S., Denniston A. K., Keane P. A., Ang M., Milea D., Chakravarthy U., Cheung C. M. G., “An overview of the clinical applications of optical coherence tomography angiography,” Eye (Lond.) 32(2), 262–286 (2018). 10.1038/eye.2017.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ang M., Tan A. C. S., Cheung C. M. G., Keane P. A., Dolz-Marco R., Sng C. C. A., Schmetterer L., “Optical coherence tomography angiography: a review of current and future clinical applications,” Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 256(2), 237–245 (2018). 10.1007/s00417-017-3896-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potsaid B., Baumann B., Huang D., Barry S., Cable A. E., Schuman J. S., Duker J. S., Fujimoto J. G., “Ultrahigh speed 1050nm swept source/Fourier domain OCT retinal and anterior segment imaging at 100,000 to 400,000 axial scans per second,” Opt. Express 18(19), 20029–20048 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.020029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y., Burnes D. L., de Bruin M., Mujat M., de Boer J. F., “Three-dimensional pointwise comparison of human retinal optical property at 845 and 1060 nm using optical frequency domain imaging,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(2), 024016 (2009). 10.1117/1.3119103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirata M., Tsujikawa A., Matsumoto A., Hangai M., Ooto S., Yamashiro K., Akiba M., Yoshimura N., “Macular choroidal thickness and volume in normal subjects measured by swept-source optical coherence tomography,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52(8), 4971–4978 (2011). 10.1167/iovs.11-7729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adhi M., Liu J. J., Qavi A. H., Grulkowski I., Lu C. D., Mohler K. J., Ferrara D., Kraus M. F., Baumal C. R., Witkin A. J., Waheed N. K., Hornegger J., Fujimoto J. G., Duker J. S., “Choroidal analysis in healthy eyes using swept-source optical coherence tomography compared to spectral domain optical coherence tomography,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 157(6), 1272–1281 (2014). 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Moreno J. M., Flores-Moreno I., Lugo F., Ruiz-Medrano J., Montero J. A., Akiba M., “Macular choroidal thickness in normal pediatric population measured by swept-source optical coherence tomography,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54(1), 353–359 (2013). 10.1167/iovs.12-10863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby M. A., Li C., Choi W. J., Gregori G., Rosenfeld P., Wang R., “Why choroid vessels appear dark in clinical OCT images,” in Ophthalmic Technologies XXVIII (2018), 10474, pp. 1047425–1047428. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olver J. M., “Functional anatomy of the choroidal circulation: methyl methacrylate casting of human choroid,” Eye (Lond.) 4(Pt 2), 262–272 (1990). 10.1038/eye.1990.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeod D. S., Lutty G. A., “High-resolution histologic analysis of the human choroidal vasculature,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35(11), 3799–3811 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramrattan R. S., van der Schaft T. L., Mooy C. M., de Bruijn W. C., Mulder P. G. H., de Jong P. T. V. M., “Morphometric analysis of Bruch’s membrane, the choriocapillaris, and the choroid in aging,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35(6), 2857–2864 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zouache M. A., Eames I., Klettner C. A., Luthert P. J., “Form, shape and function: segmented blood flow in the choriocapillaris,” Sci. Rep. 6(1), 35754 (2016). 10.1038/srep35754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nesper P. L., Soetikno B. T., Fawzi A. A., “Choriocapillaris nonperfusion is associated with poor visual acuity in eyes with reticular pseudodrusen,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 174, 42–55 (2017). 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrelli E., Uji A., Sarraf D., Sadda S. R., “Alterations in the choriocapillaris in intermediate age-related macular degeneration,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58(11), 4792–4798 (2017). 10.1167/iovs.17-22360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borrelli E., Souied E. H., Freund K. B., Querques G., Miere A., Gal-Or O., Sacconi R., Sadda S. R., Sarraf D., “Reduced choriocapillaris flow in eyes with type 3 neovascularization and age- related macular degeneration,” Retina 38(10), 1968–1976 (2018). 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Sheikh M., Phasukkijwatana N., Dolz-Marco R., Rahimi M., Iafe N. A., Freund K. B., Sadda S. R., Sarraf D., “Quantitative OCT angiography of the retinal microvasculature and the choriocapillaris in myopic eyes,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58(4), 2063–2069 (2017). 10.1167/iovs.16-21289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spaide R. F., “Choriocapillaris flow features follow a power law distribution: implications for characterization and mechanisms of disease progression,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 170, 58–67 (2016). 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uji A., Balasubramanian S., Lei J., Baghdasaryan E., Al-Sheikh M., Sadda S. R., “Choriocapillaris Imaging Using Multiple En Face Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Image Averaging,” JAMA Ophthalmol. 135(11), 1197–1204 (2017). 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.3904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montesano G., Allegrini D., Colombo L., Rossetti L. M., Pece A., “Features of the normal choriocapillaris with OCT-angiography: Density estimation and textural properties,” PLoS One 12(10), e0185256 (2017). 10.1371/journal.pone.0185256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q., Zheng F., Motulsky E. H., Gregori G., Chu Z., Chen C. L., Li C., de Sisternes L., Durbin M., Rosenfeld P. J., Wang R. K., “A novel strategy for quantifying choriocapillaris flow voids using swept-source OCT angiography,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59(1), 203–211 (2018). 10.1167/iovs.17-22953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennesi M. E., Neuringer M., Courtney R. J., “Animal models of age related macular degeneration,” Mol. Aspects Med. 33(4), 487–509 (2012). 10.1016/j.mam.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goverdhan S., Thomson H., Lotery A., “Animal models of age-related macular degeneration,” Drug Discov. Today Dis. Models 10(4), e181–e187 (2013). 10.1016/j.ddmod.2014.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An L., Shen T. T., Wang R. K., “Using ultrahigh sensitive optical microangiography to achieve comprehensive depth resolved microvasculature mapping for human retina,” J. Biomed. Opt. 16(10), 106013 (2011). 10.1117/1.3642638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang R. K., An L., Francis P., Wilson D. J., “Depth-resolved imaging of capillary networks in retina and choroid using ultrahigh sensitive optical microangiography,” Opt. Lett. 35(9), 1467–1469 (2010). 10.1364/OL.35.001467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolò M., Rosa R., Musetti D., Musolino M., Saccheggiani M., Traverso C. E., “Choroidal vascular flow area in central serous chorioretinopathy using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58(4), 2002–2010 (2017). 10.1167/iovs.17-21417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nesper P. L., Roberts P. K., Onishi A. C., Chai H., Liu L., Jampol L. M., Fawzi A. A., “Quantifying microvascular abnormalities with increasing severity of diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58(6), BIO307 (2017). 10.1167/iovs.17-21787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nesper P. L., Soetikno B. T., Fawzi A. A., “Choriocapillaris nonperfusion is associated with poor visual acuity in eyes with reticular pseudodrusen,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 174, 42–55 (2017). 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spaide R. F., “Choriocapillaris signal voids in maternally inherited diabetes and deafness and in pseudoxanthoma elasticum,” Retina 37(11), 2008–2014 (2017). 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurokawa K., Liu Z., Miller D. T., “Adaptive optics optical coherence tomography angiography for morphometric analysis of choriocapillaris [Invited],” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(3), 1803–1822 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.001803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan B., MacLellan B., Mason E., Bizheva K., “Structural, functional and blood perfusion changes in the rat retina associated with elevated intraocular pressure, measured simultaneously with a combined OCT+ERG system,” PLoS One 13(3), e0193592 (2018). 10.1371/journal.pone.0193592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alten F., Heiduschka P., Clemens C. R., Eter N., “Exploring choriocapillaris under reticular pseudodrusen using OCT-Angiography,” Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 254(11), 2165–2173 (2016). 10.1007/s00417-016-3375-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otsu N., “A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms,” IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 9(1), 62–66 (1979). 10.1109/TSMC.1979.4310076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bland J. M., An Introduction to Medical Statistics, 3rd edition, (Oxford Univ. Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo T. K., Li M. Y., “A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research,” J. Chiropr. Med. 15(2), 155–163 (2016). 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi W., Moult E. M., Waheed N. K., Adhi M., Lee B., Lu C. D., de Carlo T. E., Jayaraman V., Rosenfeld P. J., Duker J. S., Fujimoto J. G., “Ultrahigh-speed, swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography in nonexudative age-related macular degeneration with geographic atrophy,” Ophthalmology 122(12), 2532–2544 (2015). 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonas J. B., Schneider U., Naumann G. O. H., “Count and density of human retinal photoreceptors,” Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 230(6), 505–510 (1992). 10.1007/BF00181769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metelitsina T. I., Grunwald J. E., DuPont J. C., Ying G. S., Brucker A. J., Dunaief J. L., “Foveolar choroidal circulation and choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49(1), 358–363 (2008). 10.1167/iovs.07-0526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boltz A., Luksch A., Wimpissinger B., Maar N., Weigert G., Frantal S., Brannath W., Garhöfer G., Ergun E., Stur M., Schmetterer L., “Choroidal blood flow and progression of age-related macular degeneration in the fellow eye in patients with unilateral choroidal neovascularization,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51(8), 4220–4225 (2010). 10.1167/iovs.09-4968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]