Abstract

For biomedical research, successful imaging of calcified microstructures often relies on absorption differences between features, or on employing dies with selective affinity to areas of interest. When texture is concerned, e.g. for crystal orientation studies, polarization induced contrast is of particular interest. This requires sufficient interaction of the incoming radiation with the volume of interest in the sample to produce orientation-based contrast. Here we demonstrate polarization induced contrast at the calcium K-edge using submicron sized monochromatic synchrotron X-ray beams. We exploit the orientation dependent subtle absorption differences of hydroxyl-apatite crystals in teeth, with respect to the polarization field of the beam. Interaction occurs with the fully mineralized samples, such that differences in density do not contribute to the contrast. Our results show how polarization induced contrast X-ray fluorescence mapping at specific energies of the calcium K-edge reveals the micrometer and submicrometer crystal arrangements in human tooth tissues. This facilitates combining both high spatial resolution and large fields of view, achieved in relatively short acquisition times in reflection geometry. In enamel we observe the varying crystal orientations of the micron sized prisms exposed on our prepared surface. We easily reproduce crystal orientation maps, typically observed in polished thin sections. We even reveal maps of submicrometer mineralization fronts in spherulites in intertubular dentine. This Ca K-edge polarization sensitive method (XRF-PIC) does not require thin samples for transmission nor extensive sample preparation. It can be used on both fresh, moist samples as well as fossilized samples where the information of interests lies in the crystal orientations and where the crystalline domains extend several micrometers beneath the exposed surface.

1. Introduction

X-rays, by nature, have 3-5 orders of magnitude shorter wavelengths than visible light such that imaging material microstructures at the micrometer and nanometer length-scale is not diffraction limited. The ubiquity of sources producing sufficiently low energies matching absorption edges of common elements (such as iron or calcium) makes X-ray imaging attractive to measure volumes of interest spanning micrometers to millimeters, where interactions of interest arise at the angstrom or nano-scale. X-rays produced by synchrotron radiation facilities are extremely bright and can induce non-linear interactions such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF). These sources have a specific polarization vector defined by the photon source such as the insertion-device (e.g. undulator) that is positioned in the electron storage ring. Further, the energy can easily be fine-tuned by monochromators situated along the X-ray path and thus the absorption of the X-rays in the sample can be well controlled. The resulting XRF fingerprint originates from the combination of energy used, composition and the relative density of the atom species comprising the sample. By carefully selecting element-specific excitation energies, XRF spectra can provide information about the sample chemical state. For example, in solid natural materials, analysis of the X-ray absorption near-edge spectra (XANES) can be used to reveal both local changes in structure or crystal orientation through quantification of X-ray dichroism or angular absorption dependence [1]. Specifically, angular absorption dependence in combination with X-ray focusing optics and micrometer sample positioning may be used for 2D mapping of calcium containing samples found in many structures in nature. We previously demonstrated how XRF polarization induced contrast (PIC) may be used to image spatially-varying XRF signals of bone nanocrystals. To do so, energies corresponding to specific dipole transitions of calcium atoms were used to map the Ca K-edge XANES in human bone [2]. Natural mineralized samples of many types often have rather homogeneous chemical environments and minimal density variations, and it is precisely in such samples that XRF-PIC has great potential. Here we show how angular absorption dependence may be exploited to reveal micron-sized crystal orientation variations of calcium-containing crystals of apatite, by mapping micro-texture in both enamel and dentine in human teeth.

2. Background

2.1 Experimental setup and parameter

Ca near K-edge XRF mapping was conducted at the scanning X-ray microscopy end station installed at ID21 at the ESRF [3]. Measurements were performed on human teeth, collected from anonymous patients according to the guidelines of the ethics committee of the Charite-Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany. Dry tooth is reasonably stable at room temperature in vacuum and thus the samples were not measured under cryogenic conditions [4], which simplified sample preparation and repositioning. For XANES at the Ca K-edge, the highest flux on ID21 is reached when the two beamline undulators U42 are used in a synchronous manner. The fixed exit double-crystal Si(111) Kohzu monochromator was used in combination with a Ni-coated flat double-mirror. The latter filters out high-energy harmonics while the former allows to select an energy bandwidth of about 0.8 eV resolution near the Ca K-edge (4.1 keV). Downstream of the tunable monochromator, the beam was focused to a spot size of ~0.6 × 0.8 µm2 (vertical × horizontal) using a fixed-curvature Kirkpatrick-Baez mirror system yielding a flux of ~8 × 1010 photons/s (when using 180 mA current in multi-bunch mode in the synchrotron storage ring). A photodiode comprising a thin Si3N4 membrane was inserted in the beam path to continuously monitor the incoming beam intensity. XRF maps and XANES spectra were collected using a photo diode. Indeed, since the XRF spectra of tooth samples are dominated by the Ca signal, a fast photo diode capable of handling high incoming counting rates was preferred to the slower dispersive SDD detectors. A schematic sketch of the setup is given in Fig. 1.

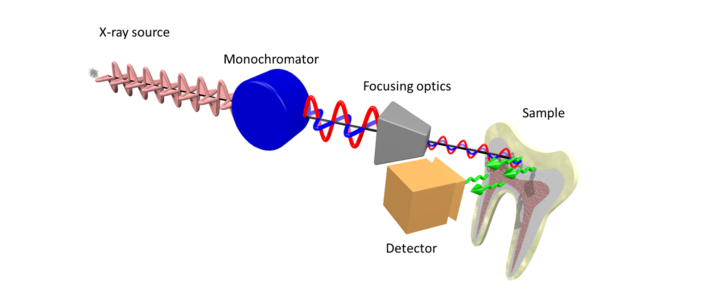

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the main optical components of the setup installed at beamline ID21 for XRF-PIC mapping. Two undulators are used to generate the X-rays that are polarized in the horizontal plane, subsequently monochromatized by a fixed exit double-crystal Si(111) Kohzu-monochromator, then focused using KB optics. The polarization orientation is not affected by any of the components downstream of the source until impinging on the sample. Following interaction with the apatite (in the tooth), non-polarized XRF radiation is generated. The total XRF signal (illustrated by green arrows) is collected by a photodiode detector.

Ca XANES spectra were collected by scanning the energy of the incoming beam from 4.032 to 4.122 keV using increments of 0.25 eV, with acquisition times of 100 ms per energy step. The XANES spectra of different enamel regions containing ordered crystal orientations were used to identify the energies with the highest polarization induced absorption contrast. For Ca in carbonated hydroxyl-apatite (c-HAP), the energies leading to electron transitions from 1s to 4p1/2 and from 1s to 4p3/2 [5] are 4.053 keV and 4.055 keV respectively [2].

2.2 Apatite crystal mapping on human tooth samples

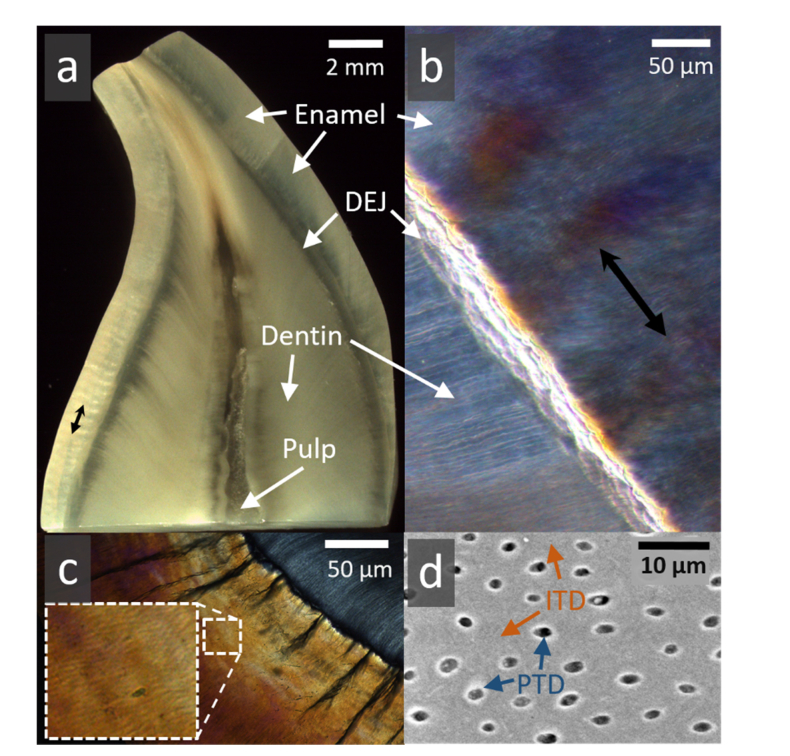

Many organisms use Ca as a readily-available major skeleton-building component, where the Ca ion is either in a carbonate (CaCO3) or in an apatite (~Ca10(PO4)6CO3OH) as is found in c-HAP [6] in bones and teeth of mammals. The apatite crystals are of prime interest for the study of bony tissues, where the nanometer-sized crystals interact with the local atomic environment (amorphous mineral, water, protein) to define the macroscopic properties of the skeletal element. Teeth are excellent examples of mineralized tissues combining several forms of the same carbonated apatite crystal, with distinctly different crystal environments and orientations in the tissues. The outer layer is enamel (Fig. 2(a)) which is highly mineralized (>90% mineral) [7] comprising clusters of elongated crystals, ~5 µm in diameter, forming highly-textured prisms (Fig. 2(c)) that merge into a hard yet brittle outer cap. Enamel prisms exhibit undulating, woven patterns and groups of similarly oriented prisms appear as bright and dark bands known as Hunter Schreger bands [8] (Fig. 2(b)). The bulk of teeth is made of dentine, a bone-like composite of nanoparticles of c-HAP mineral (~50 vol%), collagen fibers (~30 vol%) and water (~20 vol%) [9]. Dentine is highly porous as it contains tubules, approximately 1 µm in diameter, extending outwards from the pulp where they often contain cell extensions. Most tubules in the crown are lined by highly mineralized collagen-free collar of “peritubular dentine” (PTD, Fig. 2(d)). Overall, much of the dentine mass surrounding tubules comprises collagen fibers impregnated with mineral, forming “intertubular dentine” (ITD, Fig. 2(d)). Both large and small crystals of c-HAP in enamel and dentine respectively, demonstrate a measurable interaction with polarized X-rays, and both have well-documented spatial distributions [10,11].

Fig. 2.

Typical human tooth tissues (a). Cross sectional slice in a human canine crown revealing the outer enamel (worn on the upper left edge) encasing a large bulk of dentine. These 2 tissues are attached at the dentine-enamel junction (DEJ). The pulp is partially stained. (b) Higher magnification of a segment of enamel, DEJ and dentine, viewed in polarized light. Groups of alternating prism orientations in enamel (black double headed arrow) exhibit Hunter Schreger optical bands. (c) In cross section, enamel surrounds dentine (upper right) attached at the DEJ where dark tufts of organic material extend outwards (magnified area shows polarization light microscope image of clusters of enamel prisms). (d) Typical backscattered electron microscopy image of dentine containing tubules, perforating the intertubular (ITD) tissue. Tubules lie approximately 10 µm apart and are ~1 µm in diameter. Many tubules are lined by a thin highly-mineralized sheath of peritubular dentine (PTD) within ITD.

2.3 X-ray polarization induced contrast of apatite at the Ca K-edge

The angular dependence of X-ray absorption () has been previously documented [12–14]. Specifically, the underlying theoretical background is described in detail by Brouder in 1990 [15] and can be summarized as:

where is the angle between the c- axis orientation of the c-HAP crystals and the polarization vector, and and are the absorption components parallel to and perpendicular to the polarization axis, respectively.

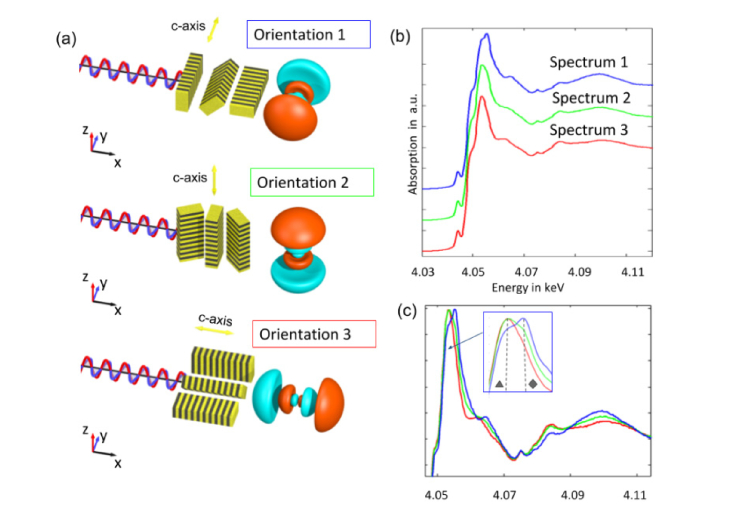

PIC of structural arrangements in Ca containing biominerals has already been reported for X-ray energies at the Ca L-edge [1,16,17]. Metzler and Rez collected Ca L-edge XANES spectra using polarized synchrotron radiation, they determined the energies for which they observed the best contrast for different c-axis orientations and subsequently collected X-ray photoemission electron microscopy (X-PEEM) maps at those energies. Ratios of maps measured near the L-edge of ~350 eV provide c-axis orientation maps of the relatively large CaCO3 crystals. Although elegant, this method is extremely surface sensitive due to the low penetration power of such low photon energies. Specifically, the photoemission electrons originate only from the very surface regions of the crystals, of which orientations may differ from the material bulk. The energies corresponding to Ca K-edge transitions exceed 4 keV and thus allow for a deeper penetration into the sample (typically ~10µm above the Ca K-edge with a CaCO3 matrix). The orientations of the Ca 4p ½ and 4p 3/2 orbitals are perpendicular to each other (Fig. 3). A double peak in the white line of Ca K-edge XANES corresponds to the 1s to 4p ½ and to 1s to 4p 3/2 (dipole-) transitions exhibiting the strongest polarization effects [2].

Fig. 3.

Polarisation effects in XANES spectroscopy at the Ca K-edge of tooth c-HAP: a) Schematic drawing of three orientations of the c-HAP crystals and the 4p3/2 orbital of Ca relative to the polarisation (along y-axis). Depending on crystal orientation with respect to the polarization axis, the interactions vary due to an angular absorption dependence. The 3D crystal orientation can be determined by sample rotation around the illumination axis. b) The XANES spectra corresponding to the three orientations shown in (a) were normalized at the edge and shifted vertically with an offset for clarity. c) Same spectra as (b) normalised to the maximum. The three spectra differ mainly in the main absorption (so called white line) region due to 1s to 4p transitions. The energies of E1 = 4.0533keV and E2 = 4.0553keV correspond to the 1s to 4p1/2 (marked ▲) and 1s to 4p3/2 (marked ♦) dipole transitions, respectively. In orientation 1, polarization is parallel to the c-HAP crystal c-axis and the 4p3/2 orbital where the probability of 1s to 4p3/2 transition is higher. In orientation 2 and 3, polarization is perpendicular to the crystals c-axis, where the probability of 1s to 4p1/2 transitions is higher.

2.4 Sample preparation and pre-characterization

The tooth samples used in this study were obtained in accordance with the Charite ethics committee guidelines, from anonymous donors, extracted during routine dental treatment. Although not essential for the method to work, mapping across reasonably flat surfaces are most practical for easy interpretation of the results. Note however, that unlike other orientation characterization sensitive methods, XRF-PIC does not need highly polished surfaces nor thin sections. In this study, and to allow comparison measurement with XRF, XANES as well as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), a human 3rd molar was dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions and embedded in PMMA. The sample was cut along the tooth axis and the exposed surfaces were ground using a series of SiC grinding papers and emery sheets to expose polished enamel and dentine surfaces. SEM imaging was performed using a HITACHI TM-1000 electron microscope at 15kV acceleration voltage, equipped with a BSE detector. For optical imaging, human incisor crowns were sliced both along and across the tooth axis, ground and polished to 200 µm thick slices and imaged in a Axioplan 2 polarizing light microscope (Zeiss Axioplan 2,Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Germany).

3. Measurements and results

3.1 Ca K-edge XANES of regions with different c-HAP orientations

XRF-PIC maps of human enamel were collected at 4.055 keV to identify regions of highest (regionHigh) and lowest (regionLow) X-ray absorption values, mapped onto the enamel prism main axis. Since the radial c-axis orientation of the prisms is known, these measurements formed the basis for subsequent collection of XANES spectra (Fig. 3). The sample region was aligned such that the dentine-enamel junction (DEJ) was aligned vertically (Fig. 4), i.e. perpendicular to the polarization vector. The absorption at this energy is higher when apatite crystals are aligned parallel with the X-ray polarization vector as compared with other orientations [2].

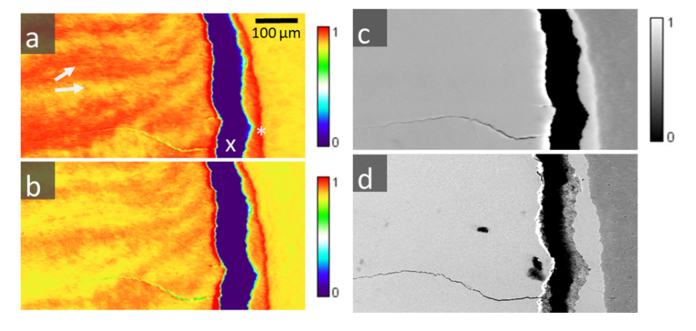

Fig. 4.

Three μXRF maps (a), (b) and (c) collected over the same region (enamel, dentine) at three different energies: a) E1 = 4.0553 keV, b) E2 = 4.0533 keV, and c) E3 = 4.2 keV, respectively. Figure d) is a backscattered SEM image of the same region, where contrast is proportional to the atomic density. The images show enamel (on the left side), a large vertical crack (indicated with an x) due to sample preparation and a small section of dentine (on the right). Enamel and dentine are typically attached at the DEJ (marked as X). At E1 and E2 (a, b) XRF-PIC reveals alternating crystalline texture of the c-HAP crystals with variations observed between adjacent prism groups (e.g. a, white arrows), similar to optically-formed Hunter Schreger bands. These effects are not visible at the higher excitation energy E3, further away from the 1s to 4p electron transition (c), where only electron density differences between enamel and dentine are observable. These are due to different Ca densities, as evidenced also by d) - backscattered electrons (SEM) of the same area as a)-c).

First, two individual XANES spectra were acquired for two different known c-axis orientations with respect to the polarization vector (Fig. 3, Orientation 1 and Orientation 3). Figure 3(b) shows the Ca K-edge XANES spectra of apatite aligned parallel (Spectrum No1 collected in regionHigh) and perpendicular (Spectrum No3 obtained in regionLow) with respect to the polarization vector. Next, to address whether the orientation distribution of the c-axis orientations from high absorption regions into low absorption regions occurs through a rotation axis parallel or perpendicular to the image plane, the sample was physically rotated by 90° (i.e. DEJ is aligned horizontally) and XANES spectra were subsequently collected on the same regions as prior to sample rotation (Spectrum No2). The XANES spectra collected after rotation no longer revealed pronounced spectral differences suggesting that the c-axis of any probed region was then perpendicular to the X-ray polarization vector. Owing to the fact that spectral changes were observed prior to sample rotation and no pronounced changes appeared in spectra after rotation, the 3D orientation vector of the c-axis distribution could be determined (see below in Fig. 5(a)-5(d)). In fact the orientation of the c-axis vector after rotation of the sample is such that it is always perpendicular to the polarization vector allowing for unique allocation of XANES spectra to the three different principal c-axis orientations (Fig. 3(b)).

Fig. 5.

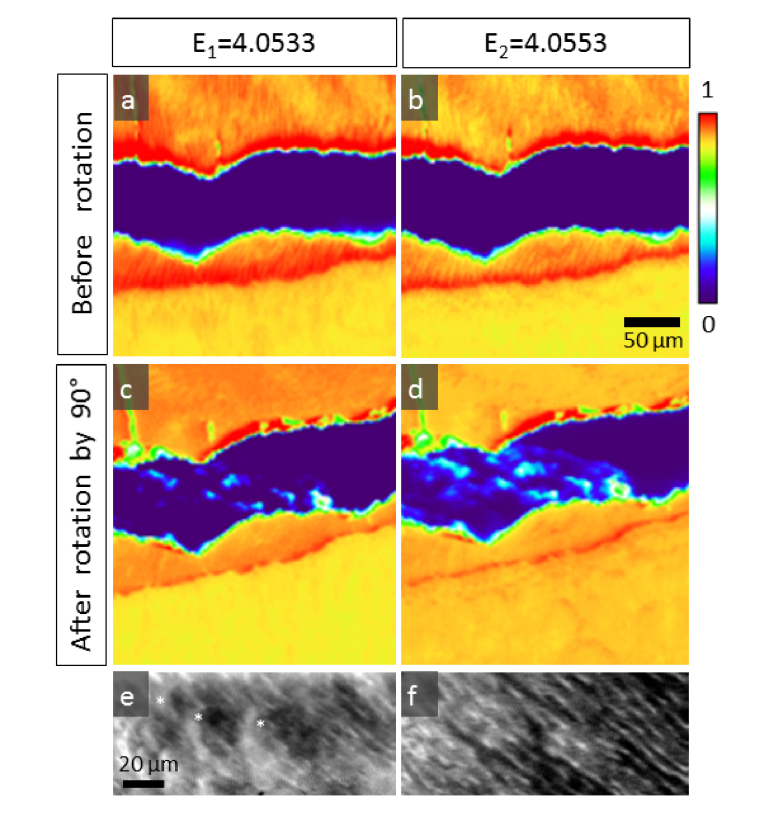

High resolution High resolution polarization sensitive μXRF maps of enamel and dentine. Maps collected at (a) E1 = 4.0533 keV and (b) E2 = 4.0553 keV reveal polarization contrast of the micro/nano crystal arrangements. Prism texture in enamel is clearly visible in the maps. Following rotation of the sample by 90° with respect to the polarization vector, the contrast between different crystal families in enamel vanishes, compare (c) at E1 = 4.0533 keV and (d) at E2 = 4.0553 keV. In dentine, spherulite curves (marked as *) are seen at E1 = 4.0533 keV (e) and peritubular dentine traces (white lines) become visible at E2 = 4.0553 keV (f).

Beyond the effects related to angular absorption dependence no spectral differences between enamel and dentine could be observed.

3.2 XRF-PIC mapping

Maps were collected at each of the two energies (which were determined above to have the best PIC) over large sample areas with acquisition time per point of 50 ms. The pixel size for collecting the XRF maps was adjusted to the regions of interest (ROI) and were 1 or 2 µm. Scans were performed in continuous (so called “zap”) mode. XRF intensity maps collected at excitation energies of 4.0553 keV (Fig. 4(a)) and 4.0533 keV (Fig. 4(b)) over the enamel near the DEJ reveal the typical prism structure, also observed by the polarization light microscope image (Fig. 2). The XRF maps highlight the enamel prisms, composed of clusters of adjacent elongated crystals (Fig. 2(c)) [18]. The high values in Fig. 4(a) correspond to regions with c-axis orientations aligned with the polarization orientation of the X-ray beam, whereas the low value corresponds to c-axis orientations perpendicular to the polarization vector. Importantly, regions of high values in Fig. 4(a) correspond to regions of low values in Fig. 4(b) and vice-versa. When the same region is mapped at E = 4.2 keV, i.e. far away from the 1s-4p transitions, the crystal pattern is no longer visible (Fig. 4(c)). The c-HAP density difference between enamel and dentine is however clearly observable since it is proportional to the mineral concentration. This is also observed in the SEM image displayed in Fig. 4(d) revealing an overall homogeneous electron density (corresponding to a uniform Ca distribution) within the enamel tissue region. Small fluctuations in dentine are due to the different tissue compositions close to the dentine tubules. Specifically, PTD is more mineralized as compared to ITD [19].

Prism texture in enamel is clearly visible in the maps shown in Fig. 5. After clockwise rotation of the sample by 90°, the contrast between different crystal families in enamel vanishes, compare (Fig. 5(c)) at E1 = 4.0533 keV and (Fig. 5(d)) at E2 = 4.0553 keV. The contrast of the prism texture in enamel is less pronounced in Fig. 5(c) and 5(d) than in Fig. 5(a) and 5(b) whereas details of the dentine microstructure emerge. Thus, the shift in orientation of adjacent enamel prisms gradually changes from prisms parallel to the polarization vector to prisms perpendicular to the polarization vector. In dentine (Fig. 5(e) and 5(f)), we clearly observe PTD in the map collected at 4.0553 keV, and spherulite curves in the same region but collected at an energy of 4.0533 keV. These features are more pronounced when the sample is oriented such that the DEJ is oriented horizontally (i.e. parallel to the polarization vector).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we showcase how XRF-PIC at excitation energies in the region of the Ca K-edge can map characteristic bio apatite crystal orientations in enamel and dentine down to the nanometer length-scale. We observe subtle changes in crystal orientations with sensitivity compared with polarized light microscopy but with much higher spatial resolution, defined by the beam geometry (focal spot). The signal that is relevant for Ca, escapes essentially only from the outer ~10 µm of the exposed sample surface. A majority of the signal arises from the outer 3 µm, and decays exponentially with increasing depth. This length-scale is very relevant for the study of mineralized tissues, as it corresponds to the typical dimension of lamella, interfaces and inclusions. Consequently, and depending on how the sample is illuminated with respect to its texture, zones in the probing-volume that contain highly-aligned clusters of crystals will show different XRF-PIC contrasts from zones with poorly co-aligned crystals. This is also seen in other techniques where the signal is integrated over the probing-volume, such as small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) or polarized Raman spectroscopy. XRF-PIC however, directly reveals mineral (apatite) crystal orientations with minimal preparation, and makes it possible to map orientations along extended sample regions in reflection. The resolution is only limited by the focusing optics and large samples can be measured while placed in a variety of in situ environments (e.g. tensile testing, annealing, hydration etc).

The XANES spectra we collected from different human enamel regions revealed the characteristic features of c-HAP [2,5,20]. Importantly, we observe three different appearances of the same Ca-containing crystals, due to the polarization-induced angular absorption dependence. Differences observed in such XANES spectra must therefore be considered when addressing subtle differences attributed to the chemical environment of calcium in c-HAP. By selecting excitation energies that are most sensitive to polarization, namely those corresponding to 1s-4p transitions, micrometric scale characteristic crystal orientation patterns in human tooth tissues are clearly revealed.

The study of (sub-) micrometer texture and arrangements of crystals in biologically formed mineralized tissue has evolved extensively over the last century [21,22]. Yet, it remains of interest due to the relevance to medicine and regeneration, and also as an inspiration for applied materials engineering sciences and biomimetics. It is accepted that the remarkable mechanical properties of these tissues arise from the hierarchical structuring of the mineralized composite and the very different micro and nano morphologies observed at different length-scales [23–26]. XRF-PIC may therefore help decipher the three dimensional arrangement of the mineral orientation patterns and in so doing, may help elucidate the role of crystal organization in the mechanical properties of these tissues [27–29].

There are several big advantages of XRF-PIC mapping as compared to other methods that exist to investigate mineralized tissues, such as SEM or X-ray diffraction [30]. (a) The use of reflection as opposed to transmission: XRF-PIC does not need thin sectioning of the sample. (b) The penetration depth of the X-rays is higher than both light and electron microscopy, and therefore provides true bulk information and not only information from the surface that might be prone to sample preparation artefacts, (c) the short wavelength of X-rays makes it possible to perform measurements far from the diffraction limit of visible light. On-going developments make it feasible to use X-ray spot sizes as small as a few tens of nm [31]. Thus, the image resolution is only limited by the spot size of the beam, which is submicrometer in size in the example here. Coupled with the fact that the X-ray interactions takes place primarily with the inner shell electrons in an atom-specific manner, X-ray methods therefore offer a different array of structural interrogation spectrum as compared with optical methods that essentially target the molecular environment.

The limitation of the presented method to gain information on apatite orientation and distinguish calcium species is clearly the need of a highly monochromatic and polarized X-ray source.

5. Conclusion

We show that polarization induced contrast X-ray fluorescence (XRF-PIC) mapping can assess crystal orientation patterns in bio minerals of human tooth samples down to the sub-micrometer length-scale. The method provides a very fast means for investigations across large sample dimensions with spatial resolutions down to sub-micron. Future developments of this technique may be applied with even smaller X-ray spot sizes, potentially only tens of nanometers, on samples that cannot be investigated non-destructively by conventional optical and electron methods.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ESRF for the allocated beamtime within experiment MD-3262. JBF acknowledges support by the US Dept. of Energy (contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344).

Funding

US Dept. of Energy (contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344).

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Metzler R. A., Rez P., “Polarization dependence of aragonite calcium L-edge XANES spectrum indicates c and b axes orientation,” J. Phys. Chem. B 118(24), 6758–6766 (2014). 10.1021/jp503565e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hesse B., Salome M., Castillo-Michel H., Cotte M., Fayard B., Sahle C. J., De Nolf W., Hradilova J., Masic A., Kanngießer B., Bohner M., Varga P., Raum K., Schrof S., “Full-Field Calcium K-Edge X-ray Absorption Near-Edge Structure Spectroscopy on Cortical Bone at the Micron-Scale: Polarization Effects Reveal Mineral Orientation,” Anal. Chem. 88(7), 3826–3835 (2016). 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotte M., Pouyet E., Salomé M., Rivard C., De Nolf W., Castillo-Michel H., Fabris T., Monico L., Janssens K., Wang T., Sciau P., Verger L., Cormier L., Dargaud O., Brun E., Bugnazet D., Fayard B., Hesse B., Pradas del Real A. E., Veronesi G., Langlois J., Balcar N., Vandenberghe Y., Solé V. A., Kieffer J., Barrett R., Cohen C., Cornu C., Baker R., Gagliardini E., Papillon E., Susini J., “The ID21 X-ray and infrared microscopy beamline at the ESRF: status and recent applications to artistic materials,” J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 32(3), 477–493 (2017). 10.1039/C6JA00356G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castillo-Michel H. A., Larue C., Pradas Del Real A. E., Cotte M., Sarret G., “Practical review on the use of synchrotron based micro- and nano- X-ray fluorescence mapping and X-ray absorption spectroscopy to investigate the interactions between plants and engineered nanomaterials,” Plant Physiol. Biochem. 110, 13–32 (2017). 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichert D., Salomé M., Banu M., Susini J., Rey C., “Preliminary characterization of calcium chemical environment in apatitic and non-apatitic calcium phosphates of biological interest by X-ray absorption spectroscopy,” Spectrochim. Acta - Part B At. Spectrosc. 60(6), 850–858 (2005). 10.1016/j.sab.2005.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowenstam H. A., Stephen W., On Biomineralization (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 16(04). [Google Scholar]

- 7.ten Cate J. M., Jongebloed W. L., Arends J., “Remineralization of artificial enamel lesions in vitro. IV. Influence of fluorides and diphosphonates on short- and long-term reimineralization,” Caries Res. 15(1), 60–69 (1981). 10.1159/000260501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch C. D., O’Sullivan V. R., Dockery P., McGillycuddy C. T., Sloan A. J., “Hunter-Schreger Band patterns in human tooth enamel,” J. Anat. 217(2), 106–115 (2010). 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01255.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg M., Kulkarni A. B., Young M., Boskey A., “Dentin: structure, composition and mineralization,” Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 3(2), 711–735 (2011). 10.2741/e281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glas J.-E., “Studies on the ultrastructure of dental enamel. II. The orientation of the apatite crystallites as deduced from X-ray diffraction,” Arch. Oral Biol. 7(1), 91–104 (1962). 10.1016/0003-9969(62)90052-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaslansky P., Maerten A., Fratzl P., “Apatite alignment and orientation at the Ångstrom and nanometer length scales shed light on the adaptation of dentine to whole tooth mechanical function,” Bioinspired, Biomim. Nanobiomaterials 2(4), 194–202 (2013). 10.1680/bbn.13.00007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Šipr O., Simůnek A., Bocharov S., Kirchner T., Dräger G., “Polarized Cu K edge XANES spectra of CuO-Theory and experiment,” J. Synchrotron Radiat. 8(2), 235–237 (2001). 10.1107/S0909049500019531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cibin G., Mottana A., Marcelli A., Brigatti M. F., “Angular dependence of potassium K-edge XANES spectra of trioctahedral micas: Significance for the determination of the local structure and electronic behavior of the interlayer site,” Am. Mineral. 91(7), 1150–1162 (2006). 10.2138/am.2006.2041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans K. A., Dyar M. D., Reddy S. M., Lanzirotti A., Adams D. T., Tailby N., “Variation in XANES in biotite as a function of orientation, crystal composition, and metamorphic history,” Am. Mineral. 99(2–3), 443–457 (2014). 10.2138/am.2014.4222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouder C., “Angular dependence of X-ray absorption spectra,” J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2(3), 701–738 (1990). 10.1088/0953-8984/2/3/018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVol R. T., Metzler R. A., Kabalah-Amitai L., Pokroy B., Politi Y., Gal A., Addadi L., Weiner S., Fernandez-Martinez A., Demichelis R., Gale J. D., Ihli J., Meldrum F. C., Blonsky A. Z., Killian C. E., Salling C. B., Young A. T., Marcus M. A., Scholl A., Doran A., Jenkins C., Bechtel H. A., Gilbert P. U. P. A., “Oxygen spectroscopy and polarization-dependent imaging contrast (PIC)-mapping of calcium carbonate minerals and biominerals,” J. Phys. Chem. B 118(28), 8449–8457 (2014). 10.1021/jp503700g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krüger P., Natoli C. R., “Theory of x-ray absorption and linear dichroism at the Ca L 23 -edge of CaCO 3,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 712, 012007 (2016). 10.1088/1742-6596/712/1/012007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller N., Ten Cate’s Oral Histology, 8th ed. BDJ 213(4), 194–194 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forien J. B., Fleck C., Cloetens P., Duda G., Fratzl P., Zolotoyabko E., Zaslansky P., “Compressive Residual Strains in Mineral Nanoparticles as a Possible Origin of Enhanced Crack Resistance in Human Tooth Dentin,” Nano Lett. 15(6), 3729–3734 (2015). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajendran J., Gialanella S., Aswath P. B., “XANES analysis of dried and calcined bones,” Mater. Sci. Eng. C 33(7), 3968–3979 (2013). 10.1016/j.msec.2013.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrof S., Varga P., Hesse B., Schöne M., Schütz R., Masic A., Raum K., “Multimodal correlative investigation of the interplaying micro-architecture, chemical composition and mechanical properties of human cortical bone tissue reveals predominant role of fibrillar organization in determining microelastic tissue properties,” Acta Biomater. 44, 51–64 (2016). 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georgiadis M., Müller R., Schneider P., “Techniques to assess bone ultrastructure organization: orientation and arrangement of mineralized collagen fibrils,” J. R. Soc. Interface 13(119), 20160088 (2016). 10.1098/rsif.2016.0088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fratzl P., Weinkamer R., “Nature’s hierarchical materials,” Prog. Mater. Sci. 52(8), 1263–1334 (2007). 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2007.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fratzl P., Gupta H. S., “Nanoscale Mechanisms of Bone Deformation and Fracture,” inHandbook of Biomineralization (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, n.d.), pp. 397–414. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ang S. F., Bortel E. L., Swain M. V., Klocke A., Schneider G. A., “Size-dependent elastic/inelastic behavior of enamel over millimeter and nanometer length scales,” Biomaterials 31(7), 1955–1963 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bechtle S., Özcoban H., Lilleodden E. T., Huber N., Schreyer A., Swain M. V., Schneider G. A., “Hierarchical flexural strength of enamel: transition from brittle to damage-tolerant behaviour,” J. R. Soc. Interface 9(71), 1265–1274 (2012). 10.1098/rsif.2011.0498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braly A., Darnell L. A., Mann A. B., Teaford M. F., Weihs T. P., “The effect of prism orientation on the indentation testing of human molar enamel,” Arch. Oral Biol. 52(9), 856–860 (2007). 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An B., Wang R., Arola D., Zhang D., “The role of property gradients on the mechanical behavior of human enamel,” J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 9, 63–72 (2012). 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Märten A., Fratzl P., Paris O., Zaslansky P., “On the mineral in collagen of human crown dentine,” Biomaterials 31(20), 5479–5490 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tadano S., Giri B., “X-ray diffraction as a promising tool to characterize bone nanocomposites,” Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 12(6), 064708 (2012). 10.1088/1468-6996/12/6/064708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cesar da Silva J., Pacureanu A., Yang Y., Bohic S., Morawe C., Barrett R., Cloetens P., “Efficient concentration of high-energy x-rays for diffraction-limited imaging resolution,” Optica 4(5), 492 (2017). 10.1364/OPTICA.4.000492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]