Abstract

Hearing aids are a demonstrated efficacious intervention for age-related hearing loss, and research suggests that good hearing loss self-management skills improve amplification satisfaction and outcomes. One way to foster self-management skills is through the provision of patient education materials. However, many of the available resources related to the management of hearing loss do not account for health literacy and are not suitable for use with adults from varying health literacy backgrounds. To address this issue, we developed the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management as part of a manualized, best practices hearing intervention used in large clinical trial. We incorporated health literacy recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in a series of modules that address a variety of common problem areas reported by adults with hearing loss. A formative assessment consisting of feedback questionnaires, semistructured interviews, and a focus group session with representatives from the target audience was conducted. Findings from the development assessment process demonstrate that the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management is suitable for use with adults with age-related hearing loss who have varying health literacy backgrounds and abilities.

Keywords: patient education, age-related hearing loss, health literacy, hearing aids

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is a highly prevalent chronic health condition with relatively low treatment uptake among U.S. adults. Between only 10 and 33% of those who could benefit from amplification report uptake of hearing aids. 1 2 3 In addition, among adults who do obtain hearing aids, a significant proportion do not use them. 4 5 6 Several factors contribute to poor treatment uptake and adherence for hearing aid use, including a lack of focus on hearing loss in older adults as a chronic condition, which can be managed but not cured. Indeed, while hearing aids are a critical component of intervention, they are not a panacea. Behavior change is necessary to reduce activity limitations and participation restrictions associated with ARHL. Research clearly supports an approach to hearing intervention that is patient centered, guided by the identification of individual needs with the setting of specific goals, engages in shared informed decision making, and fosters self-management abilities (see the British Academy of Audiology Common Principles of Rehabilitation for Adults with Hearing and/or Balance-Related Problems in Routine Audiology Services for a review). 7 The specific aim of the work described here was to develop a simple, easy to use “toolkit” that could be a part of a patient-centered approach to support self-management abilities of older adults who are first-time hearing aid users.

The impetus for the development of the Hearing Loss Toolkit ( HL Toolkit ) was the need for the manualization of an approach to best practices hearing intervention for incorporation in a large randomized controlled trial (RCT), the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) study. 8 The overarching goal of ACHIEVE is to determine if best practices hearing intervention prevents or slows down the trajectory of dementia in at-risk older adults. In preparation for the ACHIEVE trial, we conducted a feasibility study (ACHIEVE-F) of the implementation of a comprehensive approach to hearing loss intervention consisting of (1) individualized identification of needs, (2) development of individualized goals, (3) sensory management with hearing aids and other hearing assistive devices, and (4) a systematic approach to the provision of materials to support hearing loss self-management.

In our initial approach to providing materials to support hearing loss self-management and communication in real-world settings within the manualized ACHIEVE intervention protocol, we utilized written materials based on the Active Communication Education (ACE) program for adults, developed by Hickson and colleagues at the University of Queensland, Australia. 9 10 Evidence for the efficacy of ACE came from the work of Hickson et al, in which they demonstrated significantly improved self-reported outcomes related to perceptions of hearing-related handicap and self-management skills compared with a placebo program in a well-designed randomized clinical trial. 9 While the ACE program assessed was delivered in a group setting, it has also been utilized on an individual basis. 10 The individualized ACE (I-ACE) covers topics such as communication needs, improving conversation in noisy environments and around the home, hearing-assistive technologies, and understanding difficult speakers, which represent some of the most frequently reported problem areas on hearing-related questionnaires among individuals with ARHL. 11

The basic I-ACE program was modified for an American audience and supplemented with additional educational materials, including a series of reusable learning objects (RLOs) entitled C2Hear, 12 short video clips that focus on supporting new hearing aid users as they adapt to amplification. A retrospective review of feedback from participants enrolled in the ACHIEVE-F study and from a subsequent pilot study (ACHIEVE-P) of all trial procedures 8 revealed that despite modification of the program, the I-ACE was perceived as being too lengthy, and had information that was irrelevant to the participants' self-identified difficult listening situations. In addition, it was perceived as not being visually interesting. Finally, a majority of participants reported that while the information included was probably very useful, they did not attempt the at-home exercises due to the perceived time commitment.

Several reasons may account for the lack of reputed adherence to the use of the modified I-ACE program. First, although the ACE program demonstrated efficacy among an Australian audience, it is possible that the materials did not generalize to a U.S. audience. A second possible reason for the lack of adherence was that the modifications made did not account for what is known about health literacy and best practices patient education in the United States. In light of the feedback received on the I-ACE, we decided that a more streamlined, individualized approach for hearing loss self-management materials that took into account varying health literacy abilities and that was built on the evidence-base for patient education materials (PEMs) was warranted. The concept of health literacy and its role in developing PEMs are described later.

Health Literacy

Health literacy mediates the relationship between education and health outcomes, including health care use and treatment adherence. 13 14 Health literacy is the ability to understand and act on health information (e.g., read health-related text or instructions, interpret labels and prescriptions, or adhere to treatment recommendations). These essential skills enable an individual to take an active part in his or her health care decisions and management. Not surprisingly, health literacy relates to general literacy, which for adults is defined as the ability to read prose, use documents appropriately, and perform quantitative tasks (i.e., numeracy). 15 Limited health literacy is associated with several negative outcomes, including low use of preventative health care services, increased emergency room visits and hospitalizations, inaccurate interpretation of medication labels and inappropriate medication use, poorer self-management of chronic health conditions such as asthma and diabetes, and poorer health status and quality of life. 16

Although there are currently no population-based studies that approximate the prevalence of low health literacy, it is estimated that about half of adults in the United States lack the skills to optimally function in a literate society. 17 Defining the multifaceted construct of literacy level can be a challenge. The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine suggests five levels of prose literacy based on ascending reading difficulty, with levels 1 (at or below a fifth grade reading level) and 2 (between a fifth and eighth grade reading level) being the lowest proficiency levels. 15 Using this scale, approximately 21 and 27% of adults perform at levels 1 and 2, respectively, meaning that just under half of all U.S. adults read at or below an eighth grade level. Low and limited prose literacy certainly affect a patient's ability to read and understand health-related education materials, which are frequently distributed as a means to relay important health information. In light of this, The Joint Commission, a certification and accreditation body for over 21,000 health care organizations in the United States, recommended that all PEMs be prepared at a fifth grade reading level or lower. 18 Despite the Joint Commission recommendation, the majority of written PEMs distributed exceed a literacy level appropriate for U.S. adults, including information for parents, 19 general ambulatory care information, 20 information available on an online patient portal, 21 and information instructing patients on important issues relevant to the self-management of a chronic health condition, including hearing loss. 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Health Literacy Recommendations for Patient Education Materials

Several strategies have been suggested to improve the understandability of PEMs to make them suitable for patient populations with a wide variety of health literacy abilities. In 2010, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) released a national action plan for improving health literacy. 29 After an in-depth review of the research, the DHHS reported that low health literacy could successfully be addressed, and provided evidence-based methods for improving PEMs. The evidence strongly supported the development of PEMs with input from the end-user, termed participatory design, which can account for differences in health literacy levels. Including members of the target audience in PEM development resulted in better health-related outcomes across several studies reviewed by the DHHS. 29 The action plan additionally advocated for simple, straightforward language without excessive medical terminology, noting that everyone, even those with high levels of health literacy, benefits from clear, jargon-free communication. Finally, the action plan called for targeted, tailored materials adapted to meet the needs of those with limited health literacy, citing improvements in treatment and medication adherence as positive outcomes when such types of PEMs are used. 29

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) adapted the DHHS recommendations and identified actions health care providers and organizations could take to improve the health literacy of their patient populations. 30 A primary aim of the CDC action plan was to provide guidance for health providers and organizations on the development of PEMs. This was done in part by identifying major attributes that reduce barriers to health care information for people from a wide range of health literacy abilities, which include (1) end-user participatory design frameworks, (2) avoiding stigmatization of individuals with low or limited health literacy, (3) clear oral communication strategies, and (4) PEMs that are easy to understand and actionable. 30

With regard to PEMs, several techniques address the DHHS and CDC recommendations for increasing health literacy. One such technique is the use of straightforward, jargon-free plain language in PEMs. Numerous resources exist for evaluating the understandability of text. Readability formulas, such as the Flesch-Kincaid grade level equation, 31 are commonly used. The majority of these formulas score written text by estimating the difficulty of the vocabulary and sentence structure, and frequently report results as a grade level (e.g., a fifth grade reading level). 32 Note that there are drawbacks of using readability formulas to determine the understandability of PEMs. Automated readability formulas do not take into account much more than letter number, and syllable and sentence lengths, assuming that longer equals more difficult. In other words, readability formulas often do not take ease of readability, sometimes obtained by use of a longer phrase or sentence, into account when estimating a difficulty level. Compound sentences might aid an end-user in making connections between important points—a shorter sentence is not always a better sentence. Readability formulas also do not take into account when a complex term is defined in plain language, which is often a primary aim of PEMs. In other words, the formula artificially inflates the difficulty level when, in fact, the text may be suitable.

Despite these drawbacks, automated readability formulas can be helpful as a starting point for developing PEMs, particularly if using a variety in conjunction with hand scoring. Automated formulas assist in the identification of longer words and sentences that might be difficult for the target audience to understand. 30 Another resource available to increase the understandability of text in PEMs is the CDCs list of “Everyday Words for Public Health Communication.” 33 This document provides plain-language alternatives for commonly used medical terms and gives examples of both the medical term and the plain-language term in sentences ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Examples of “Everyday Words for Public Health Communication” (Source: Centers for Disease Control).

| Health terminology | Alternative everyday words | Example |

|---|---|---|

| “Associated with” | “Linked to” “Goes along with” “Is part of” “Related to” |

Instead of: “ Hearing loss is associated with other health problems ” Use: “ Other health problems go along with hearing loss ” |

| “Evaluation” | “Test” | Instead of: “ Now it's time to go over the results of your hearing evaluation ” Use: “ Let's go over your hearing test results ” |

| “Global” “Globally” |

“Around the world” “In the world” “Countries other than the US” |

Instead of: “ Hearing loss effects millions of people globally ” Use: “ Millions of people around the world have hearing loss ” |

| “Intervention” | “Program” “Action” “Treatment” |

Instead of: “You will receive hearing aids and counseling as part of your intervention” Use: “You will get hearing aids and counseling as part of your treatment” |

| “Maintain” | “Take care of” “Keep up” “Look after” |

Instead of: “It is important to maintain your hearing aids by keeping them clean” Use: “It is important to take care of your hearing aids by keeping them clean” |

In addition to using plain language, linking pictures with important text is another technique that is particularly effective in improving the communication of important health information to the target audience. In a systematic review assessing the effects of pictures on health information, Houts et al 34 examined evidence on four primary aspects of health communication: (1) drawing attention to the message, (2) increasing comprehension, (3) increasing recall, and (4) increasing adherence. Their findings suggest that including pictures in PEMs results in improvements in all four communication aspects. Since the review of Houts et al, several studies have demonstrated improvements in patient outcomes following the use of illustrated, plain-language PEMs, including better adherence to medication schedules, 35 improved preparation for colonoscopy, 36 and better self-management of diabetes. 37 With regard to hearing health education, Convery et al 38 demonstrated that provision of PEMs using simple line-drawn images accompanied by plain-language captions facilitated successful completion of a variety of hearing aid self-management tasks in two groups of patients with varying health literacy levels from developing countries.

Despite the positive findings of Convery et al, 38 the incorporation of best-practice health literacy principles into PEM development is an area that is lacking in the field of audiology. Unfortunately, most studies in the hearing health care field demonstrate that current PEMs provided to individuals with hearing loss are largely unsuitable. For example, Nair and Cienkowski found a mismatch in literacy levels between hearing aid orientation information (written on average at a ninth grade reading level) provided to new users (all participants under a fourth grade reading level, n = 12). 27 Caposecco et al 26 investigated the suitability of 36 different hearing aid user guides with a group of older adults. Four different readability tools (Flesch Reading Ease Scale, Fry Readability Graph, Flesh-Kincaid Readability Formula, and Fog Index) analyzed the suitability of the user guides, and revealed a 9.6 average-grade literacy level. In addition, the authors evaluated the user guides' content, expected literacy level of the reader, general readability, graphic content, layout, and cultural appropriateness using the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) tool, which is designed to assess health materials in a standardized manner. On the abovementioned criteria, the authors concluded that 69% of printed hearing aid user guides were unsuitable for their intended audience. Furthermore, 90% of the guides used excessive technical jargon and 100% of the guides utilized a font size that was too small. In a subsequent study examining behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid PEMs from each major manufacturer, Joseph et al 39 also found that overall readability far exceeded health literacy best practice recommendations. Specifically, portions of user guides addressing hearing aid self-management skills demonstrated reading levels ranging from 8th to 12th grades, with an average of 10.7. While these studies serve as an excellent starting point from which to examine currently available materials, the analyses primarily focused on grade-level literacy estimates, which is a limitation. Further research is needed to determine the influence of best practice health literacy guidelines on the understanding of hearing health PEMs.

In developing the HL Toolkit , we sought to consider the DHHS and CDC recommendations for creating printable PEMs suitable for use with adults with ARHL who may have limited or low health literacy. The HL Toolkit includes plain language text, images, and action plans designed to assist new hearing aid users adapt to amplification in the context of their own lives. The materials focus on a variety of topics related to self-management of hearing loss, such as the fundamentals of the ear and hearing, communication strategies for people with hearing loss, speech understanding in noise, and hearing technology. In the following sections, we describe the development of the printed HL Toolkit , and a formative assessment conducted with a targeted audience representative of the end-users, and discuss implications for practice.

Method

All study procedures involving human subjects, including recruitment, informed consent, and protocols, were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of South Florida in Tampa, FL.

Toolkit Development

The following are the steps for developing the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management (referred to as the HL Toolkit ).

1. Identification of important concepts to be included:

As a starting point, we included main concepts from the I-ACE program as part of the HL Toolkit content (hearing in noise, communication strategies, and HATs). We additionally included topics that were ranked the highest in importance on the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) 11 questionnaires completed by ACHIEVE-F and -P participants ( n = 40). The COSI is a self-report questionnaire that instructs a client with hearing loss to identify and prioritize up to five specific, difficult to listening situations s/he would most like to improve. Following a hearing intervention, such as use of amplification and/or aural rehabilitation over a prescribed time interval, the client then reports the degree of improvement seen for each of the identified situations. The audiologist then chooses 1 of 16 categories for each identified goal. For the HL Toolkit development, five independent audiologists reviewed 127 COSI goals (average: 3.17 per participant) and assigned a category to each goal. We then collapsed the 16 categories into 9 in an effort to streamline the HL Toolkit content. Table 2 shows the revised and original COSI goal categories, prioritized by participants.

Table 2. Revised and original COSI Goal Categories Used in the HL Toolkit .

| Importance | Revised COSI goal category | Original COSI goal category |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | TV/Radio at normal volume | TV/Radio at normal volume |

| 2 | Conversation in noise | Conversation with 1 or 2 in noise |

| Conversation with group in noise | ||

| 3 | Conversation in quiet | Conversation with 1 or 2 in quiet |

| Conversation with group in quiet | ||

| 4 | Church/Meeting | Church/Meeting |

| 5 | Telephone conversations | Familiar speaker on the phone |

| Unfamiliar speaker on the phone | ||

| 6 | Hear traffic | Hear traffic |

| 7 | Phone/Doorbell ring | Hear phone ring from another room |

| Hear front door bell or knock | ||

| 8 | Psychosocial adjustment | Increase social contact |

| Feel embarrassed or stupid | ||

| Feel left out | ||

| Feel upset/angry | ||

| 9 | Other | Other |

2. Description of HL Toolkit materials design incorporating best-practice health literacy recommendations:

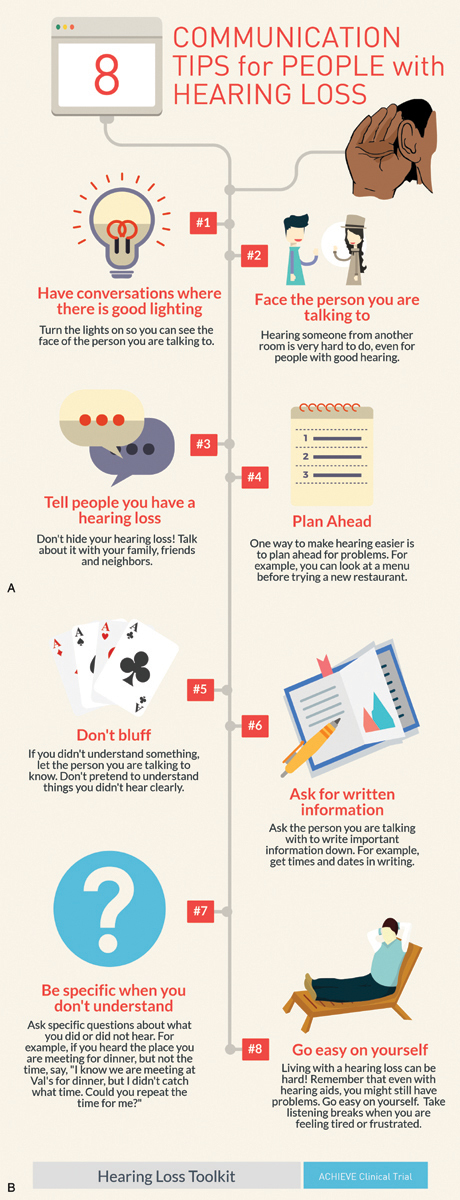

Each module of the HL Toolkit is between two and five pages in length, and includes a brief introduction, an infographic containing the majority of the educational content, a summary, and a Listening Goal Action Plan. To create these materials, we performed the procedures described in this section. Following selection of content, the first four HL Toolkit sections (described in Table 3 ) were designed using best-practice health literacy recommendations set forth by the DHHS and CDC. The cloud-based program Piktochart ( https://piktochart.com/ ) was used to create the printed materials, and initial assessment of understandability was completed using the Readability Test Tool ( https://www.webpagefx.com/tools/read-able/ ). The Readability Test Tool simultaneously estimates Flesch-Kincaid reading ease and grade level, the Gunning FOG index, the Coleman Liau index, the automated readability index, and the SMOG index; however, we focused only on the Flesch-Kincaid reading ease and grade level scores and the Gunning FOG index, as these are the measures most often cited in the literature. The Readability Test Tool revealed that text included in the first four HL Toolkit sections was at approximately a sixth grade level, with no portions averaging higher than an eighth grade level. Following the initial understandability assessment, we made further modifications to the materials using the CDC recommendations specific to written content 32 (e.g., eliminating “walls” of text, ensuring cohesive font, colors, and pictures were used throughout, defining medical terms clearly, including culturally diverse images). Examples from each of the first four HL Toolkit sections are displayed in Fig. 1 .

Table 3. Content Overview of Four Initial HL Toolkit Sections .

| Title | Content overview |

|---|---|

| “Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals” | • Basic hearing loss facts • Description of type, degree, and configuration of hearing loss • Includes person's hearing plotted on a “familiar sounds audiogram” • Includes goal setting using the COSI |

| “Communication Strategies” | • Describes eight suggestions for improved communication • Provides examples such as adequate lighting, asking for clarification, facing the talker • Introduces the “Listening Goal Action Plan” |

| “Hearing and Understanding in Noise” | • Describes common sources of noise • Provides fast and easy tips for improving hearing in noise • Includes the “Listening Goal Action Plan” |

| “What are Hearing Assistive Technologies?” | • Defines the term “Hearing Assistive Technologies (HATs)” • Explains how HATs work with hearing aids • Describes four common HATs and how they function • Includes the “Listening Goal Action Plan” |

Figure 1.

Example inforgraphic excerpt from the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management(c).

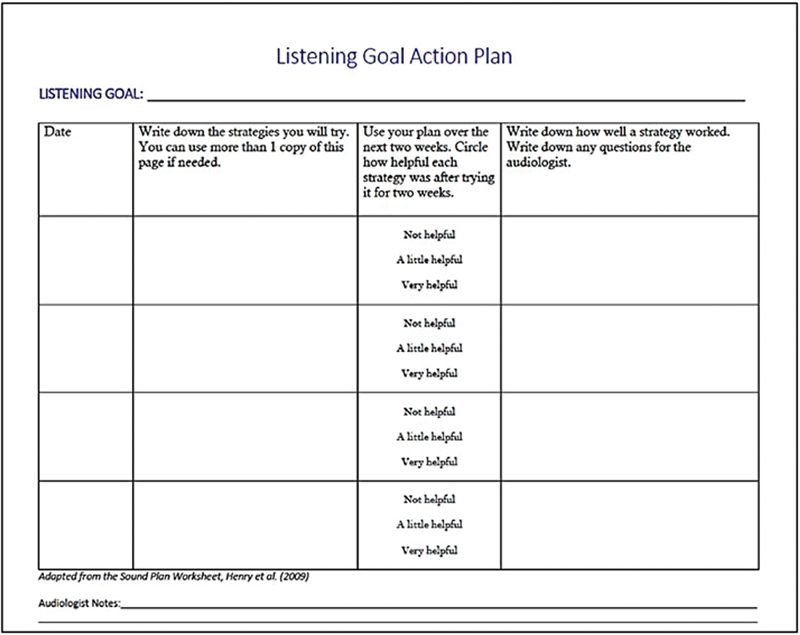

The COSI and a corresponding Listening Goal Action Plan for each module were included to streamline and individualize the HL Toolkit . The Listening Goal Action Plan ( Fig. 2 ) was modeled after the Sound Plan Worksheet, developed by Henry et al as part of the Progressive Tinnitus Management (PTM) program, 40 used throughout the Veterans' Administration healthcare system. Similar to the COSI, the Sound Plan Worksheet asks a client to identify and rank their most bothersome tinnitus situations. After receiving PTM education, the client writes down what strategies, techniques, or devices s/he will use to manage the bothersome tinnitus situation, try the plan over the course of 2 weeks, and rank the usefulness of each strategy, technique, and/or device. For the HL Toolkit , individuals complete the COSI with an audiologist to identify and prioritize difficult listening situations, receive educational modules related to those situations, use the Listening Goal Action Plan to select strategies from the modules to try over the course of 2 weeks, and finally rank the usefulness of the strategies.

Figure 2.

Example of the “Listening Goal Action Plan” from the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management(c), adapted from the Sound Plan Worksheet (Henry et al., 2009).

3. Materials review by hearing experts prior to end-user assessment:

The four concept HL Toolkit modules ( Table 3 ) were next reviewed by two clinical audiologists not involved in the material development using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's (AHRQ) Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT). 41 The PEMAT was developed to provide a systematic method of evaluating and comparing the understandability and actionability of PEMs. Understandability refers to whether or not the PEMs are understandable to consumers of diverse backgrounds and varying levels of health literacy, such that they can process and explain key messages. Actionability refers to whether or not the PEMs are actionable, that is, can consumers of diverse backgrounds and varying levels of health literacy identify what they can do based on the information presented. 41 The PEMAT can be used by health care professionals or others tasked with providing high-quality materials to patients or consumers. Two PEMAT tools are available, one for printed materials (PEMAT-P) and one for audiovisual materials (PEMAT-AV). Detailed information about the development of the PEMAT can be found at http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/self-mgmt/pemat/index.html .

The PEMAT-P checklist consists of 19 items addressing understandability and 7 items addressing actionability , for a total of 26 items. For each item, a rater selects either “Agree” (1 point), “Disagree” (0 points), or “Not Applicable.” A percent score is then calculated for each of the two constructs. PEMs are considered acceptable if the scores are 80% or better for each construct. PEMAT-P checklists were completed by the two audiologists for each of the four HL Toolkit modules. Feedback from the audiologists was positive, with PEMAT-P scores greater than 90% for both understandabilit y and actionability for each of the four HL Toolkit sections assessed. suggesting that the materials were suitable for use with patients of varying levels of health literacy. 41

Toolkit Assessment

Design . We used a formative assessment approach to generate primarily qualitative end-user opinion on the understandability and actionability of the printed materials from the HL Toolkit .

Target audience

. End users from the target audience (

n

= 10) were recruited from the sample of individuals who completed ACHIEVE-F using the initial I-ACE materials. End users ranged in age from 71 to 83 years (

= 77.3). Of the ten, five were women and five were men. All participants were native speakers of American English. The ACHIEVE-F study required that participants have a mild to moderately severe gradually sloping bilateral symmetrical sensorineural hearing loss (500, 1,000, 2,000 Hz pure-tone average of 30 dB HL or worse in the better ear). Furthermore, as a part of the ACHIEVE-F study, all participants were fit bilaterally with receiver-in-the-canal hearing aids and were provided a hearing HAT to facilitate in meeting individualized COSI goals for intervention.

Table 4

displays demographic, hearing loss, and hearing device information for end users included in the current study.

= 77.3). Of the ten, five were women and five were men. All participants were native speakers of American English. The ACHIEVE-F study required that participants have a mild to moderately severe gradually sloping bilateral symmetrical sensorineural hearing loss (500, 1,000, 2,000 Hz pure-tone average of 30 dB HL or worse in the better ear). Furthermore, as a part of the ACHIEVE-F study, all participants were fit bilaterally with receiver-in-the-canal hearing aids and were provided a hearing HAT to facilitate in meeting individualized COSI goals for intervention.

Table 4

displays demographic, hearing loss, and hearing device information for end users included in the current study.

Table 4. Demographic, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Technology Information for the Participants.

| Participant | Age | Gender | 3-Frequency average (0.5, 1, 2 kHz) | Hearing aid | Hearing assistive technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83 | M | 43 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

ComPilot Air II Remote Mic |

| 2 | 80 | F | 45 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

TV Link II Remote |

| 3 | 74 | M | 30 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

ComPilot II TV Link |

| 4 | 77 | F | 48 dB HL | Starkey Z Series i110 |

SurfLink Mobile SurfLink Media |

| 5 | 77 | M | 50 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

ComPilot TV Link |

| 6 | 80 | M | 30 dB HL | Starkey Z Series i110 |

SurfLink Mobile |

| 7 | 71 | M | 42 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

ComPilot Air II SurfLink Media |

| 8 | 84 | M | 52 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

TV Link Compilot |

| 9 | 76 | F | 38 dB HL | Phonak Audéo V90–312 T |

Compilot Air II Remote Mic |

| 10 | 71 | F | 30 dB HL | Starkey Z Series i110 |

Remote |

Assessment instruments. Four HL Toolkit modules were assessed ( Table 3 ) using feedback questionnaires and open-ended interviews developed by two audiologists with extensive experience in adult audiological intervention and patient education. Following is a description of each of the assessment instruments.

Feedback questionnaire. We adapted items most relevant to end-users from the full PEMAT-P checklist to include in the feedback questionnaire (shown in Tables 5 and 6 ). Seven items were asked regarding understandability (one open-ended and six Likert questions), and three were asked regarding actionability (one yes/no, one open-ended, and one Likert question). For the Likert items, the end-users were asked to rate their level of agreement on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The third columns of Tables 5 and 6 display the items included on the feedback questionnaire.

Table 5. PEMAT-P items: Understandability.

| Item no. | Item | How item was addressed in questionnaire |

|---|---|---|

| Topic: content | ||

| 1 | The material makes its purpose completely evident | (1) The title tells me what this handout is about |

| 2 | The material does not include information or content that distracts from its purpose | (5) There is too much information in this handout |

| Topic: word choice and style | ||

| 3 | The material uses common, everyday language | N/A |

| 4 | Medical terms are used only to familiarize audience with the terms. When used, medical terms are defined | (3) I can understand all of words in this handout (2) This handout is hard to read |

| 5 | The material uses the active voice | N/A |

| Topic: use of numbers | ||

| 6 | Numbers appearing in the material are clear and easy to understand | N/A |

| 7 | The material does not expect the user to perform calculations | N/A |

| Topic: organization | ||

| 8 | The material breaks or “chunks” information into short sections | N/A |

| 9 | The material's sections have informative headers | (1) The title tells me what this handout is about |

| 10 | The material presents information in a logical sequence | (6) I can easily find the information I need about a topic (2) This handout is hard to read |

| 11 | The material provides a summary | N/A |

| Topic: layout and design | ||

| 12 | The material uses visual cues (e.g., arrows, boxes, bullets, bold, larger font, highlighting) to draw attention to key points | (6) I can easily find the information I need about a topic (2) This handout is hard to read |

| Topic: use of visual aids | ||

| 15 | The material uses visual aids whenever they could make content more easily understood (e.g., illustration of healthy portion size) | (4) I like the colors and pictures |

| 16 | The material's visual aids reinforce rather than distract from the content | N/A |

| 17 | The material's visual aids have clear titles or captions | N/A |

| 18 | The material uses illustrations and photographs that are clear and uncluttered | (4) I like the colors and pictures |

| 19 | The material uses simple tables with short and clear row and column headings | N/A |

Table 6. PEMAT-P Items: Actionability.

| Item no. | Item | How item was addressed in questionnaire |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | The material clearly identifies at least one action the user can take | (7) I learned something new after reading this handout |

| 21 | The material addresses the user directly when describing actions | N/A |

| 22 | The material breaks down any action into manageable, explicit steps | N/A |

| 23 | The material provides a tangible tool (e.g., menu planners, checklists) whenever it could help the user take action | N/A |

| 24 | The material provides simple instructions or examples of how to perform calculations | N/A |

| 25 | The material explains how to use the charts, graphs, tables, or diagrams to take actions | N/A |

Semistructured interview guide. In addition to the questionnaire, we developed a semistructured interview guide to lead the conversation between the researcher and the end-users during the evaluation of the HL Toolkit . The interview guide highlighted several discussion topics with the intent on generating feedback on the following PEMAT-P assessment areas: (1) understandability, (2) medical terms defined, (3) font size and style, (4) images, (5) layout, and (6) content of information. Additional questions included in the semistructured interview guide included the following: “ What module of the Toolkit was most/least useful to you?”; “Is there any missing information that is important to you?”; “ Overall, how would you improve the Toolkit?” and “Comparing the I-ACE to the Toolkit, which do you prefer and why?”

Procedures . The evaluation of the HL Toolkit occurred on two sessions: an individual feedback and interview session and a focus group session.

Session 1. Session 1 lasted for 60 to 90 minutes, and included administration of the four HL Toolkit sections followed by completion of the feedback questionnaire and semistructured interview. Each end-user was shown the modules in the following order: (1) hearing loss and your listening goals ; (2) communication strategies ; (3) hearing and understanding in noise ; and (4) What are Hearing Assistive Technologies? . The researcher read the text aloud, covering each page of each module of the HL Toolkit as the end-user followed along. Upon a complete review of each module of the HL Toolkit , end-users completed a feedback questionnaire (totaling four questionnaires). Participants could view the HL Toolkit modules and ask the researcher questions while completing the paper form.

Following administration of the HL Toolkit and completion of the feedback questionnaires, a semistructured interview was conducted. During the interview, end-user feedback was elicited for each of the individual pages of the HL Toolkit to ensure that all included PEMAT-P assessment areas were discussed at some point. Each semistructured interview was audio recorded for further analysis.

Session 2. After completion of individual sessions, we invited five individuals who provided the most insightful feedback to participate in a focus group. Three were able to attend the focus group. The aim of the focus group was to generate feedback related to themes not uncovered in any of the previously mentioned methods, as recommended by Knudsen et al. 42 The focus group followed a format similar to the semistructured interview; however, each question generated a discussion among the group. End-users additionally spoke about their hearing loss journey and related it to topics covered in the HL Toolkit . The focus group session was audio recorded for further analysis.

Results

Results obtained from the rating items reported on the individually administered feedback questionnaire are presented first, followed by the results obtained from the semistructured interviews and focus group session.

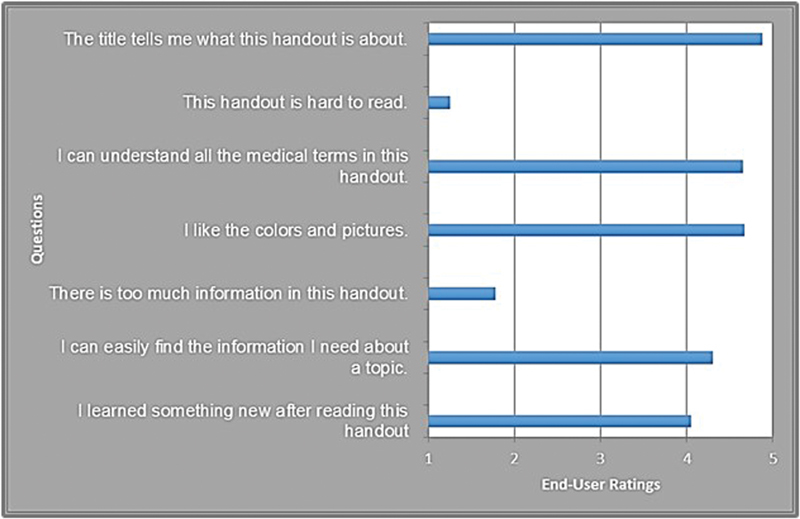

Feedback Questionnaire and Individual Semistructured Interview Results

Feedback questionnaire results for each module of the HL Toolkit are presented in full in Table 7 and Fig. 3 shows the mean ratings collapsed across modules obtained from the feedback questionnaires. Specifically, the majority of end-users strongly agreed or agreed that (Item 1) the titles told what the modules were about; (Item 3) the medical terminology was understandable; (Item 4) the aesthetics were visually pleasing; (Item 6) information could easily be found; and (Item 7) new information was learned from the modules. For items with reverse scoring, the majority of end-users strongly disagreed or disagreed that (Item 2) the modules were hard to read; and (Item 5) there was too much information presented. Review of the data in Table 7 shows that the average pattern of results was reflected in the response patterns for each of the individual modules.

Table 7. End-user Feedback Questionnaire Responses for the Hearing Loss Toolkit .

| Title: “Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Strongly agree/Agree | Neither agree or disagree | Strongly disagree/Disagree |

| Title tells what about | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Hard to read | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Medical terminology | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Visually pleasing | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Too much information | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Information easy to find | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| New information learned | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| Title: “ Communication Strategies ” | |||

| Item | Strongly agree/Agree | Neither agree or disagree | Strongly disagree/Disagree |

| Title tells what about | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Hard to read | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Medical terminology | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Visually pleasing | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Too much information | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| Information easy to find | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| New information learned | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Title: “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise” | |||

| Item | Strongly agree/Agree | Neither agree or disagree | Strongly disagree/Disagree |

| Title tells what about | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Hard to read | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Medical terminology | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| Visually pleasing | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Too much information | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Information easy to find | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| New information learned | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Title: “What are Hearing Assistive Technologies?” | |||

| Item | Strongly agree/Agree | Neither agree or disagree | Strongly disagree/Disagree |

| Title tells what about | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Hard to read | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Medical terminology | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Visually pleasing | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Too much information | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Information easy to find | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| New information learned | 8 | 2 | 0 |

Figure 3.

Mean end-user ratings of the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management(c) from the feedback questionnaires.

In reviewing the transcripts of the audio recordings of the interviews, feedback was generally in agreement with the feedback questionnaire responses. However, some participants suggested providing more information on the cause of hearing loss, and said the images on the included familiar sound audiogram could be more sophisticated. After reviewing each of the four modules and completing the feedback questionnaire and semistructured interview, end-users were asked to select which modules were the most and least useful to them. The majority of end-users rated the modules “ Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals ” and “ Communication Strategies ” the most useful and “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” and “ What are Hearing Assistive Technologies? ” the least useful. Follow-up questioning on why the most useful modules were rated as such was primarily themed around the quality and usefulness of the information (for the “ Communication Strategies ” module) and the individualization achieved through including the personal audiogram and COSI goals within the module pages themselves (for the “ Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals ” module). For the least useful modules, users reported that the information was slightly redundant or common knowledge (for the “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” module). Regarding the HATs module, end-users found the information useful, but had already received HATs along with multiple orientation and education visits with an audiologist as part of ACHIEVE-F. Therefore, the information was not rated as highly useful as the other modules. Detailed results are displayed in Table 8 .

Table 8. Most and Least Useful HL Toolkit modules .

| Title | Most Useful ( n ) | Least Useful ( n ) |

|---|---|---|

| “Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals” | 5 | 1 |

| “Communication Strategies” | 4 | 1 |

| “Hearing and Understanding in Noise” | 0 | 4 |

| “What are Hearing Assistive Technologies?” | 1 | 4 |

Focus Group Results

Prior to the focus group, we discussed end-user feedback received at Session 1 and made a few preliminary modifications to the HL Toolkit . These included a change in font color on page 4 of the What are Hearing Assistive Technologies? module from white to black, as that was the most common suggestion. We additionally modified the cover image for the Communication Strategies module from a checklist image to a group of individuals sitting around a table talking to one another. No additional modifications were made based on other recommended suggestions and feedback received during the Session 1, with the idea that the focus group discussion would guide these final decisions.

During the focus group session, end-users ( n = 3) were presented with the updated HL Toolkit that included the minor modifications discussed earlier. Common themes that arose during the focus group evaluation process determined the final changes we subsequently made to the HL Toolkit . Overall findings were again very positive. The majority of the feedback focused around the “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” module and various suggestions were made to improve it. Table 9 displays the common themes/suggestions for change, along with how we addressed each suggestion. The final version of the Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Table 9. Focus Group Results.

| Themes/suggestions | n | How addressed |

|---|---|---|

| There should be a fact about hearing loss and withdrawing from social situations [in the “ Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals ” module] | 3 | Included a fact in the module addressing withdrawal and social isolation. Further, we created an additional module that focused on psychosocial effects of hearing loss |

| Use simpler more common terms for frequency and decibel on the “Familiar Sounds” audiogram [in the “ Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals ” module] | 3 | These terms were defined in plain language terms (i.e., “pitch” and “loudness”) within the body text of the module |

| I don't know what the bubbles on the title page mean, maybe add a person or a group image [on the “ Communication Strategies ” module] | 1 | Image on the cover page was changed from conversation bubbles to a group of people sitting around a table |

| Why do we need the 3 tips at all? [in the “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” module]. The graphic says where the noise is coming from, you don't need the 3 tips | 3 | The 3 tips were removed and a graphic of a cell phone was added |

| Add cell phone as another noise source, and then make the graphics bigger [in the “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” module] | 3 | The graphic sizes were increased, and an image and text for “phones” were added |

| Change header text from “steps to improve conversations in noise” to “ways to improve conversations in noise” [in the “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” module] | 3 | Modified the section header to reflect this suggestion |

| Speech in noise image is difficult to understand [in the “ Hearing and Understanding in Noise ” module] | 3 | We opted to keep this image; did not make the change at this time |

Discussion

The goal of the present project was to develop and assess PEMs aimed at increasing the hearing loss self-management skills of adults from varying health literacy backgrounds. Adults with higher levels of education are more likely to report obtaining and regularly using hearing aids. 3 43 44 45 This relationship is not surprising given that years of schooling is strongly predictive of adults' use of health services, leaving significant chronic conditions such as hearing loss to go unaddressed. 46 Given its large prevalence, untreated ARHL poses a major public health dilemma, as it is significantly associated with falls, increased hospitalizations, social isolation, and dementia. 47 48 49 50 Therefore, increasing the understanding of ARHL and educating at-risk populations about the importance of hearing health care services should be a major public health objective.

Using best practice health literacy recommendations from the DHHS, CDC, and AHRQ, we designed a series of modules focused on common listening difficulties experienced by adults with ARHL. The assessed learning modules included in the HL Toolkit were (1) Hearing Loss and Your Listening Goals ; (2) Communication Strategies ; (3) Hearing and Understanding in Background Noise ; and (4) What are Hearing Assistive Technologies? Following review from two clinical audiologists, we obtained feedback from representatives of the target audience in terms of end-user understandability and actionability of the materials through feedback questionnaires, semistructured interviews, and a focus group. Overall, the HL Toolkit was well received by both audiologists and end-users; however, modifications to the modules were made based on the feedback.

Results from the current study suggest that the HL Toolkit meets best practice recommendations for patient health information. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the HL Toolkit successfully relays information that can be understood and acted upon by persons with varying levels of health literacy. As suggested by previous research, there is a lack of appropriate hearing loss and self-management materials that take into account education and health literacy levels. Furthermore, low health literacy is believed to be a contributing factor to poor ARHL treatment uptake and adherence. Therefore, the development of PEMs addressing hearing health is an important step in addressing this issue. Indeed, three government agencies focusing on the health of the U.S. population (CDC, DHHS, and AHRQ) stress the importance and need for these types of health education materials.

Recently, attention has been paid to the relationship between health literacy and hearing health outcomes in the area of novel service delivery models that aim to increase hearing health care access to unserviced and underserviced populations. Examples of such models currently being explored in the area of hearing health provision include over-the-counter hearing aid delivery and self-fitting hearing aids, 51 52 53 community-based hearing health provision, 54 and tele-audiology. 55 However, without the direct guidance of a hearing health professional, the patient bears much of the onus of responsibility for self-management of a hearing impairment. Therefore, particular attention must be paid to the understandability and actionability of PEMs delivered within these models to ensure they are suitable for audiences with varying health literacy backgrounds. Furthermore, designing PEMs in accordance with health literacy guidelines may facilitate novel hearing health care service delivery by both reducing costs associated with hearing health care and increasing access to care in areas that are remote and/or developing.

Our study has several strengths. First, we relied heavily on end-user participatory design for the prospective development of the HL Toolkit modules. Utilization of the values, goals, beliefs, and preferences of the target audience when developing PEMs is a primary component of both the DHHS and CDC action plans for increasing health literacy in the United States. 29 30 56 By investigating COSI responses, we were able to identify goals generated and prioritized by members of the target audience: adults with ARHL. We additionally elicited feedback from target end-users, and incorporated modifications into the HL Toolkit based on their suggestions. A second strength is related to the systematic, rigorous method that we utilized to develop the HL Toolkit . By tracking each developmental stage and the resources used throughout the process, others interested in developing PEMs in accordance with best health literacy practices can easily replicate these methods. While we made efforts to incorporate inclusive images and language in the HL Toolkit, we were limited in that participants who completed the formative assessment were largely white; future studies are currently taking place that include participants from racially diverse populations. An additional limitation is that we piloted only the first four modules of the HL Toolkit, and subsequently developed an additional five modules based on our experience and results. Ideally, formative assessments will be completed for all nine of the HL Toolkit modules.

Effective patient education is key for patient engagement and optimized health outcomes, particularly for the management of chronic health conditions. Supporting the abilities of individuals with diverse backgrounds through efforts to improve health literacy is a major health policy issue of both the CDC and the DHHS. Audiology providers and researchers must recognize that most currently available PEMs are not appropriate for the vast majority of patients seen. Improving the quality, inclusivity, and accessibility of the PEMs we provide, patients with ARHL should be a priority among hearing health care professionals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIA R34AG046548 and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation. The authors would like to thank Ann Eddins, Kathryn Hyer, Louise Hickson, Ariane Laplante-Lévesque, Frank Lin, and Laura Westermann for their contributions and feedback.

References

- 1.Bainbridge K E, Ramachandran V. Hearing aid use among older U.S. adults; the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2005-2006 and 2009-2010. Ear Hear. 2014;35(03):289–294. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000441036.40169.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin F R, Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(05):582–590. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popelka M M, Cruickshanks K J, Wiley T L, Tweed T S, Klein B E, Klein R. Low prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults with hearing loss: the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(09):1075–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chia E M, Wang J J, Rochtchina E, Cumming R R, Newall P, Mitchell P. Hearing impairment and health-related quality of life: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear. 2007;28(02):187–195. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market. Hearing Review. 2009;16:12–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laplante-Lévesque A, Hickson L, Worrall L. Rehabilitation of older adults with hearing impairment: a critical review. J Aging Health. 2010;22(02):143–153. doi: 10.1177/0898264309352731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.British Society of Audiology.Common principles of rehabilitation for adults with hearing- and/or balance-related problems in routine audiology services2012. Available at: http://www.thebsa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/BSA_PPC_Rehab_Final_30August2012.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019

- 8.Deal J A, Albert M S, Arnold M et al. A randomized feasibility pilot trial of hearing treatment for reducing cognitive decline: results from the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot Study. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017;3(03):410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickson L, Worrall L, Scarinci N. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the active communication education program for older people with hearing impairment. Ear Hear. 2007;28(02):212–230. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laplante-Lévesque A. The University of Queensland, Australia; 2009. Individualized Active Communication Education. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8(01):27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson M, Brandreth M, Brassington W, Leighton P, Wharrad H. A Randomized controlled trial to evaluate the benefits of a multimedia educational program for first-time hearing aid users. Ear Hear. 2016;37(02):123–136. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Heide I, Wang J, Droomers M, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Uiters E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J Health Commun. 2013;18 01:172–184. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schillinger D, Barton L R, Karter A J, Wang F, Adler N. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(03):245–254. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirsch I R, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L

- 16.Berkman N D, Sheridan S L, Donahue K E, Halpern D J, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(02):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer A M, Kindig D . Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2004. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Joint Commission.Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis T C, Mayeaux E J, Fredrickson D, Bocchini J A, Jr, Jackson R H, Murphy P W. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials. Pediatrics. 1994;93(03):460–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis T C, Crouch M A, Wills G, Miller S, Abdehou D M. The gap between patient reading comprehension and the readability of patient education materials. J Fam Pract. 1990;31(05):533–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stossel L M, Segar N, Gliatto P, Fallar R, Karani R. Readability of patient education materials available at the point of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(09):1165–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2046-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zion A B, Aiman J. Level of reading difficulty in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists patient education pamphlets. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74(06):955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eltorai A E, Sharma P, Wang J, Daniels A H. Most American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons' online patient education material exceeds average patient reading level. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(04):1181–1186. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh J. Research briefs reading grade level and readability of printed cancer education materials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(05):867–870. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.867-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hearth-Holmes M, Murphy P W, Davis T C et al. Literacy in patients with a chronic disease: systemic lupus erythematosus and the reading level of patient education materials. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(12):2335–2339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caposecco A, Hickson L, Meyer C. Hearing aid user guides: suitability for older adults. Int J Audiol. 2014;53 01:S43–S51. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.832417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair E L, Cienkowski K M. The impact of health literacy on patient understanding of counseling and education materials. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(02):71–75. doi: 10.3109/14992020903280161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laplante-Lévesque A, Brännström K J, Andersson G, Lunner T. Quality and readability of English-language internet information for adults with hearing impairment and their significant others. Int J Audiol. 2012;51(08):618–626. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.684406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDCs Health Literacy Action Plan. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/planact/cdcplan.html. Accessed January 8, 2018

- 31.Kincaid J P, Fishburne J, Robert P . Defense Technical Information Center; 1975. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.Toolkit for Making Written Material Clear and Effective2012

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Everyday words for public health communication Washington, DC: CDC; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houts P S, Doak C C, Doak L G, Loscalzo M J. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(02):173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kripalani S, Robertson R, Love-Ghaffari M H et al. Development of an illustrated medication schedule as a low-literacy patient education tool. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(03):368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tae J W, Lee J C, Hong S J et al. Impact of patient education with cartoon visual aids on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(04):804–811. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seligman H K, Wallace A S, DeWalt D A et al. Facilitating behavior change with low-literacy patient education materials. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31 01:S69–S78. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Convery E, Keidser G, Caposecco A, Swanepoel W, Wong L L, Shen E. Hearing-aid assembly management among adults from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: toward the feasibility of self-fitting hearing aids. Int J Audiol. 2013;52(06):385–393. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.773407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joseph J, Svider P F, Shaigany K et al. Hearing aid patient education materials: is there room for improvement? J Am Acad Audiol. 2016;27(04):354–359. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henry J A, Stewart B J, Griest S, Kaelin C, Zaugg T L, Carlson K. Multisite randomized controlled trial to compare two methods of tinnitus intervention to two control conditions. Ear Hear. 2016;37(06):e346–e359. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoemaker S J, Wolf M S, Brach C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(03):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knudsen L V, Laplante-Lévesque A, Jones L et al. Conducting qualitative research in audiology: a tutorial. Int J Audiol. 2012;51(02):83–92. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.606283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer M E, Cruickshanks K J, Wiley T L, Klein B E, Klein R, Tweed T S. Determinants of hearing aid acquisition in older adults. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(08):1449–1455. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garstecki D C, Erler S F. Hearing loss, control, and demographic factors influencing hearing aid use among older adults. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1998;41(03):527–537. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4103.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nieman C L, Marrone N, Szanton S L, Thorpe R J, Jr, Lin F R. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in hearing health care among older Americans. J Aging Health. 2016;28(01):68–94. doi: 10.1177/0898264315585505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker D W, Parker R M, Williams M V, Clark W S, Nurss J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(06):1027–1030. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boi R, Racca L, Cavallero A et al. Hearing loss and depressive symptoms in elderly patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12(03):440–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin F R, Metter E J, O'Brien R J, Resnick S M, Zonderman A B, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(02):214–220. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genther D J, Frick K D, Chen D, Betz J, Lin F R. Association of hearing loss with hospitalization and burden of disease in older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2322–2324. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin F R, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(04):369–371. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Convery E, Keidser G, Dillon H, Hartley L. A self-fitting hearing aid: need and concept. Trends Amplif. 2011;15(04):157–166. doi: 10.1177/1084713811427707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Humes L E, Rogers S E, Quigley T M, Main A K, Kinney D L, Herring C. The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Audiol. 2017;26(01):53–79. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keidser G, Dillon H, Flax M, Ching T, Brewer S. The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiology Res. 2011;1(01):e24. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2011.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coco L, Champlin C A, Eikelboom R H.Community-based intervention determines tele-audiology site candidacy Am J Audiol 201625(3S):264–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferguson M, Henshaw H. Computer and internet interventions to optimize listening and learning for people with hearing loss: accessibility, use and adherence. Am J Audiol. 2015;24(03):338–343. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJA-14-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.America's Health Literacy: Why We Need Accessible Health InformationAn Issue Brief from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008