Abstract

Plant root colonization by rhizobacteria can protect plants against pathogens and promote plant growth, and chemotaxis to root exudates was shown to be an essential prerequisite for efficient root colonization. Since many chemoattractants control the transcript levels of their cognate chemoreceptor genes, we have studied here the transcript levels of the 27 Pseudomonas putida KT2440 chemoreceptor genes in the presence of different maize root exudate (MRE) concentrations. Transcript levels were increased for 10 chemoreceptor genes at low MRE concentrations, whereas almost all receptor genes showed lower transcript levels at high MRE concentrations. The exposure of KT2440 to different MRE concentrations did not alter c-di-GMP levels, indicating that changes in chemoreceptor transcripts are not mediated by this second messenger. Data suggest that rhizosphere colonization unfolds in a temporal fashion. Whereas at a distance to the root, exudates enhance chemoreceptor gene transcript levels promoting in turn chemotaxis, this process is reversed in root vicinity, where the necessity of chemotaxis toward the root may be less important. Insight into KT2440 signaling processes were obtained by analyzing mutants defective in the three cheA paralogous genes. Whereas a mutant in cheA1 showed reduced c-di-GMP levels and impaired biofilm formation, a cheA2 mutant was entirely deficient in MRE chemotaxis, indicating the existence of homologs of the P. aeruginosa wsp and che (chemotaxis) pathways. Signaling through both pathways was important for efficient maize root colonization. Future studies will show whether the MRE concentration dependent effect on chemoreceptor gene transcript levels is a feature shared by other species.

Keywords: chemotaxis, chemoreceptor, Pseudomonas, root exudates, root colonization

Introduction

Bacteria adapt to changing environmental conditions through different signal transduction systems that most commonly include one- and two-component systems as well as chemosensory pathways (Galperin, 2005; Laub and Goulian, 2007; Hazelbauer et al., 2008). In the latter systems, the direct binding of chemoeffectors or chemoeffector-loaded periplasmic binding proteins to the ligand binding domain (LBD) of chemoreceptors causes a molecular stimulus that is transmitted across the membrane where it modulates the autokinase activity of the CheA histidine kinase and consequently transphosphorylation to the CheY response regulator, which generates ultimately the pathway output (Hazelbauer et al., 2008). Typically, the adaptation of pathway sensitivity to the ambient chemoeffector concentration is achieved through the action of CheR methyltransferases and CheB methylesterases. Chemosensory pathways have been initially described to mediate chemotaxis (Parkinson et al., 2015). However, other studies show that these pathways can also be responsible for type IV pili-based motility (Whitchurch et al., 2004) or mediate alternative cellular functions (Wuichet and Zhulin, 2010).

Escherichia coli is the traditional model to study chemosensory pathways. This bacterium has four chemotaxis and an aerotaxis receptor that feed into a single pathway (Parkinson et al., 2015). However, the complexity of chemosensory signaling mechanisms depends on the bacterial lifestyles (Alexandre et al., 2004; Lacal et al., 2010b). Metabolically versatile bacteria that are able to inhabit different ecological niches were found to possess many more chemoreceptors, up to 80, whereas niche-specific bacteria contain fewer receptors (Lacal et al., 2010b). In addition, many bacteria possess multiple chemosensory pathways (Hamer et al., 2010; Wuichet and Zhulin, 2010), which adds to the complexity.

The colonization of plant roots by beneficial rhizobacteria is a process of enormous relevance since it was shown promote plant growth and to induce a systemic resistance of plants to different pathogens (Pieterse et al., 2014; Vejan et al., 2016). Chemotaxis of beneficial bacteria to plant root exudates is a necessary requisite for efficient root colonization (de Weert et al., 2002; Allard-Massicotte et al., 2016; Scharf et al., 2016). Plant root exudates are very complex compound mixtures of primary and secondary metabolites (Badri and Vivanco, 2009; van Dam and Bouwmeester, 2016; Petriacq et al., 2017) and chemotaxis to many individual constituents of root exudates, mainly primary metabolites, has been reported (Webb et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2018; Matilla and Krell, 2018). In this study we have used maize root exudates (MRE) that were shown in previous studies to contain primary metabolites like sugars, sugar acids, organic acids and amino acids (Kraffczyk et al., 1984; Carvalhais et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2012). In addition, a large series of other compounds were detected in MRE such as benzylamines, polyamines, pyrrol derivatives, fatty acids, nucleotide derivatives, purines, steroids, phytohormones, phenylpropanoids, terpenoids, flavonoids, and benzoxazinoids (Kidd et al., 2001; Neal et al., 2012; da Silva Lima et al., 2014; Petriacq et al., 2017). Although these latter compounds are generally exuded in smaller quantities, some of them were shown to be important in plant-to-microorganism signaling (Hassan and Mathesius, 2012).

Pseudomonas putida strains are metabolically versatile and respond chemotactically to a wide range of compounds (Parales et al., 2015; Sampedro et al., 2015). To analyze the influence of MRE on chemoreceptor gene transcript levels, we have used P. putida KT2440 (Belda et al., 2016) in this study as a model organism. This strain was isolated from soil, is nutritionally versatile, has a saprophytic lifestyle, colonizes plant roots efficiently and is able to protect plants against phytopathogens through the induction of systemic resistance or using type VI secretion systems (Bagdasarian et al., 1981; Espinosa-Urgel et al., 2002; Nakazawa, 2002; Regenhardt et al., 2002; Matilla et al., 2010; Bernal et al., 2017). KT2440 has 27 different chemoreceptors and research over mainly the last decade has permitted to gain insight into the function of more than half of them (Table 1). These chemoreceptors were found to respond to different organic and amino acids, polyamines, purine bases, gamma-aminobutyric acid, cyclic organic acids, inorganic phosphate or changes in the energy status.

Table 1.

Pseudomonas putida KT2440 chemoreceptors.

| Locus tag (chemoreceptor name) | Chemoeffector/comment | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PP_0317 (McpR) | Succinate, malate, fumarate | Parales et al., 2013 |

| PP_0320 (McpH) | Adenine, guanine, hypoxanthine, xanthine, uric acid, purine | Fernandez et al., 2016 |

| PP_0562 (CtpL_PP) | Inorganic phosphate (by homology with P. aeruginosa) | Wu et al., 2000; Ortega et al., 2017 |

| PP_1228 (McpU) | Putrescine, spermidine, cadaverine, agmatine, ethylenediamine, histamine | Corral-Lugo et al., 2016; Corral-Lugo et al., 2018; Gavira et al., 2018 |

| PP_1371 (McpG) | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | Reyes-Darias et al., 2015 |

| PP_1488 (WspA_PP) | Unknown/WspA homolog, mutation reduces biofilm formation | Corral-Lugo et al., 2016; Ortega et al., 2017 |

| PP_2111 (Aer2) | Energy taxis | Sarand et al., 2008 |

| PP_2120 (CtpH_PP) | Inorganic phosphate (by homology with P. aeruginosa) | Wu et al., 2000; Ortega et al., 2017 |

| PP_2249 (McpA) | Gly, L-isomers of Ala, Cys, Ser, Asn, Gln, Phe, Tyr, Val, Ile, Met, Arg | Corral-Lugo et al., 2016 |

| PP_2257 (Aer1) | Energy taxis? | Sarand et al., 2008 |

| PP_2310 | Mutation increases biofilm formation | Corral-Lugo et al., 2016 |

| PP_2643 (PcaY_PP) | Different cyclic acids | Luu et al., 2015; Fernandez et al., 2017 |

| PP_2861 (McpP) | Pyruvate, L-lactate, propionate, acetate | Garcia et al., 2015 |

| PP_4521 (Aer3) | Energy taxis? | Sarand et al., 2008 |

| PP_4658 (McpS) | Malate, fumarate, oxaloacetate, succinate, citrate, isocitrate, butyrate | Lacal et al., 2010a; Lacal et al., 2011; Pineda-Molina et al., 2012 |

| PP_4888 | Expression regulated by benzoxazinoids | Neal et al., 2012 |

| PP_5020 (McpQ) | Citrate, citrate/metal2+ | Martin-Mora et al., 2016 |

This strain has 27 chemoreceptors and listed are the receptors for which information on their function are available. Indicated are the corresponding chemoreceptor ligands and references.

KT2440 also has three copies of each of the chemosensory signaling proteins suggesting that they assemble to three different signaling pathways. Of the three cheA paralogs, cheA1 (Supplementary Figure S1) is within a gene cluster that shares high sequence similarity with the wsp cluster of P. aeruginosa encoding a pathway that is not related to chemotaxis but that modulates c-di-GMP levels and consequently biofilm formation (Hickman et al., 2005). The notion that this pathway in KT2440 has a similar function is supported by the observation that the deletion of the cheR1 gene of the same cluster largely reduced biofilm formation (Garcia-Fontana et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that the deletion of cheR2 (Supplementary Figure S1) abolished chemotaxis (Garcia-Fontana et al., 2013) and we hypothesize that cheR2 and genes of the cluster harboring cheA2 encode the proteins of a chemotaxis pathway. The function of cheA3 (Supplementary Figure S1) and its neighboring signaling genes remains unknown.

We have published recently a study in which we have investigated the effect of different stimuli on the KT2440 chemoreceptor gene transcript levels (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). Apart from the culture medium and growth phase, we were able to show that many chemoeffectors regulate the transcript levels of their cognate chemoreceptor genes. In particular, different C2- and C3-carboxylic acids, amino acids, cyclic carboxylic acids, putrescine as well as different purine derivatives increased the transcript levels of their cognate chemoreceptor genes, whereas inorganic phosphate reduced transcript levels of both of its cognate receptor genes. Interestingly, most of these chemoeffectors were shown to be present in MRE (Carvalhais et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2012). In this study we investigate the effect of different MRE concentrations on chemoreceptor gene transcript levels. We show that responses depend largely on the MRE concentration, with increase in transcript levels at low MRE concentrations and a general reduction at elevated concentrations. Data reported provide novel insight into the nature and mechanisms of bacterial responses in the rhizosphere.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Plasmids and Primers

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2, whereas oligonucleotides are provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 lacU169 (Ø80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 (rk-mk-), recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Woodcock et al., 1989 |

| CC118λpir | araD Δ(ara, leu) ΔlacZ74 phoA20 galK thi-1rspE rpoB argE recA1 λpir | Herrero et al., 1990 |

| HB101 | F- Δ(gpt-proA)62 leuB6 supE44 ara-14 galK2 lacY1 Δ(mcrC-mrr) rpsL20 (SmR) xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 thi-1 | Boyer and Roulland-Dussoix, 1969 |

| BL21 (DE3) | F- ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB (rB-mB-) λ(DE3) | Jeong et al., 2009 |

| Pseudomonas putida | ||

| KT2440 | Wild type; Derivative of P. putida mt-2, cured of pWWO | Belda et al., 2016 |

| KT2440R | RifR derivative of P. putida KT2440; wild type | Espinosa-Urgel and Ramos, 2004 |

| KT2440RTn7-Sm | Extragenic site-specific insertion of miniTn7; RifR, SmR | Matilla et al., 2007 |

| KT2440R_CheA1 | pp1492::mini-tn5-Km; RifR, KmR | Duque et al., 2007 |

| KT2440R_CheA2 | Δpp4338::km; constructed by marker exchange, RifR,KmR | This study |

| KT2440R_CheA3 | pp4988::mini-tn5-Km; RifR, KmR | Duque et al., 2007 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28b(+) | KmR; Protein expression plasmid | Novagen |

| pRK600 | CmR; mob tra | Finan et al., 1986 |

| pUC18Not | ApR; identical to pUC18 but with two NotI sites flanking pUC18 polylinker | Herrero et al., 1990 |

| p34S-Km3 | KmR, ApR; Km3 antibiotic cassette | Dennis and Zylstra, 1998 |

| pKNG101 | SmR; oriR6K mob sacBR | Kaniga et al., 1991 |

| pCdrA::gfpC | ApR, GmR; FleQ dependent c-di-GMP biosensor | Rybtke et al., 2012 |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | GmR; oriRK2 mobRK2 | Kovach et al., 1995 |

| pPP4888 | KmR; pET28b(+) derivative containing DNA fragment encoding PP4888-LBD cloned into NdeI and BamHI sites | This study |

| pMAMV287 | ApR; 2.2-kb BamHI/HindIII PCR product containing a fragment of pp4338 was inserted into the same sites of pUC18Not | This study |

| pMAMV289 | ApR, KmR; a 0.8-kb PstI fragment internal to pp4338 of pMAMV287 was replaced for a 1-kb PstI fragment containing km3 cassette of p34S-Km3 | This study |

| pMAMV290 | SmR, KmR; 2.4-kb NotI fragment of pMAMV289 was cloned at the same site in pKNG101 | This study |

aAp, ampicillin; Gm, gentamycin; Km, kanamycin; Rif, rifampin; Sm, streptomycin.

Table 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Description/purpose |

|---|---|---|

| PP4338-BamHI-F | TAATGGATCCAAGCGCGTCACCACACTG | Forward primer for mutagenesis of PP_4338 |

| PP4338-HindIII-R | TAATAAGCTTGTACGCGACAGGTCGAGGTG | Reverse primer for mutagenesis of PP_4338 |

| PP4888LBD-NdeI-F | AACATATGACCCGAAGCACGGTCACCGCC | Forward primer to clone the region encoding PP4888-LBD into pET28b(+) |

| PP4888LBD-BamHI-R | AAGGATCCCTAGCGCAGCTCGGCAGCCGCAT | Reverse primer to clone the region encoding PP4888-LBD into pET28b(+) |

| qPP_McpR_F | CATACTGGTTGGCGGCTTTT | RT-qPCR of PP_0317 (mcpR) |

| qPP_McpR_R | TCCGAGCAGATCAACAAGGT | RT-qPCR of PP_0317 (mcpR) |

| qPP_0320_F | ACCGGCCATTACTACAACGA | RT-qPCR of PP_0320 (mcpH) |

| qPP_0320_R | ATGTTGATGAACCGTTCGGC | RT-qPCR of PP_0320 (mcpH) |

| qPP_CtpL_F | TGCTGGTGACCGTGTGTATC | RT-qPCR of PP_0562 (ctpL_PP) |

| qPP_CtpL_R | CCCAGATAGCGCTCCATCAG | RT-qPCR of PP_0562 (ctpL_PP) |

| qPP_McpU_F | ATTGGCCTGTACCTGGTGTT | RT-qPCR of PP_1228 (mcpU) |

| qPP_McpU_R | GGGACCAGTACAGCGAGAAA | RT-qPCR of PP_1228 (mcpU) |

| qPP_McpG_F | CTTCCTCACGGTCTACCTGG | RT-qPCR of PP_1371 (mcpG) |

| qPP_McpG_R | GTTCATGCCGTCCTTGTACC | RT-qPCR of PP_1371 (mcpG) |

| qPP_1488_F | TGCTGATCAGGCATCCAGTC | RT-qPCR of PP_1488 (wspA_PP) |

| qPP_1488_R | AAGCTTGGCATTGACCAGGT | RT-qPCR of PP_1488 (wspA_PP) |

| qPP_2111_F | GAGATCAGCCGCAACATCAG | RT-qPCR of PP_2111 (aer2) |

| qPP_2111_R | GTCAGTTCTTCGCTCAGCAG | RT-qPCR of PP_2111 (aer2) |

| qPP_CtpH_F | ATGCAGCAGACCATCGACAT | RT-qPCR of PP_2120 (ctpH_PP) |

| qPP_CtpH_R | TTTGCCTATCCGTGTGCTGT | RT-qPCR of PP_2120 (ctpH_PP) |

| qPP_McpA I2_F | AGCAGACCAACCTGCTGGCACTGAAC | RT-qPCR of PP_2249 (mcpA) |

| qPP_McpA_R5 | TGCCATCGATTTCGCCAATG | RT-qPCR of PP_2249 (mcpA) |

| qPP_2257_F4 | ACTGCAATGAACCAGATGGC | RT-qPCR of PP_2257 (aer1) |

| qPP_2257_R3 | CAGGTTGGTTTGCTCGGC | RT-qPCR of PP_2257 (aer1) |

| qPP_2643_F | GGAGCTGAACAACAAGAGCC | RT-qPCR of PP_2643 (pcaY_PP) |

| qPP_2643_R | CGTATTCGGCAAAGGTAGCC | RT-qPCR of PP_2643 (pcaY_PP) |

| qPP_McpP_F | CAAGGCCATAGACACCAGCA | RT-qPCR of PP_2861 (mcpP) |

| qPP_McpP_R | CGTTCAATGCGGTGAGGTTG | RT-qPCR of PP_2861 (mcpP) |

| qPP_4521_F | GAAACCATCAAGCAGGGCAA | RT-qPCR of PP_4521 (aer3) |

| qPP_4521_R | TGATCCGGCCTTGTTCGTAT | RT-qPCR of PP_4521 (aer3) |

| qPP_McpS_F | ATCCAGTCGATGAACCAGCA | RT-qPCR of PP_4658 (mcpS) |

| qPP_McpS_R | TTTGCTCTGACACATCACGC | RT-qPCR of PP_4658 (mcpS) |

| qPP_McpQ_F | CCGTGATGTACTGGGTAGCA | RT-qPCR of PP_5020 (mcpQ) |

| qPP_McpQ_R | CGTGCTGGTACTGGTTGATG | RT-qPCR of PP_5020 (mcpQ) |

| qPP_0584_F | ATTTCAAGCAGCTGGGAAGC | RT-qPCR of PP_0584 |

| qPP_0584_R | CATGTAGTGCACGCCATTGA | RT-qPCR of PP_0584 |

| qPP_0779_F | AGCAAGAAATCCGGCAACTG | RT-qPCR of PP_0779 |

| qPP_0779_R | TTGACCATCTCGATCCGTCC | RT-qPCR of PP_0779 |

| qPP_1819_F | ACAACCTTGATGTGCTGCAG | RT-qPCR of PP_1819 |

| qPP_1819_R | TTGCTCAAGAAACTCGCCAC | RT-qPCR of PP_1819 |

| qPP_1940_F | CGTGTTTGAGCCGTTCTTCA | RT-qPCR of PP_1940 |

| qPP_1940_R | GAACCGACCCGCTTATTGTC | RT-qPCR of PP_1940 |

| qPP_2310_F | CGACAACTAGCCGAGGACAG | RT-qPCR of PP_2310 |

| qPP_2310_R | GCTTCGATGGCAGCGTTAAG | RT-qPCR of PP_2310 |

| qPP_2823_F | CCAGGCATAACATCGACAGC | RT-qPCR of PP_2823 |

| qPP_2823_R | CTTCCAGTTGTTCCATGGCC | RT-qPCR of PP_2823 |

| qPP_3414_F | AGCAGATTTCCCAGGAGCTT | RT-qPCR of PP_3414 |

| qPP_3414_R | CCCGAATGGTCAGCACAATC | RT-qPCR of PP_3414 |

| qPP_3557_F | AATTGGGCAGCAACGAAACC | RT-qPCR of PP_3557 |

| qPP_3557_R | GTTGGCCATGTCATGTTCGG | RT-qPCR of PP_3557 |

| qPP_3950_F | TACCTGTTCATGGCGCAATC | RT-qPCR of PP_3950 |

| qPP_3950_R | ACCGTTCTTGAGGTTTTCGC | RT-qPCR of PP_3950 |

| qPP_4888_F | CATTCAGGCGCACATTACCG | RT-qPCR of PP_4888 |

| qPP_4888_R | AACAACCCTTCACTCGCCTT | RT-qPCR of PP_4888 |

| qPP_4989_F | CATCAACGGCATGGACAACA | RT-qPCR of PP_4989 |

| qPP_4989_R | GATGTCGCCGATTTCCTGTG | RT-qPCR of PP_4989 |

| qPP_5021_F | TAGGCCTGATCAACGACCTG | RT-qPCR of PP_5021 |

| qPP_5021_R | TGGTCGAGGATGTTGCTGAT | RT-qPCR of PP_5021 |

| qPP_0387_F | AGGAAATCAACCGTCGCATG | RT-qPCR of PP_0387 (rpoD) |

| qPP_0387_R | GGTTGGTGTACTTCTTGGCG | RT-qPCR of PP_0387 (rpoD) |

| qPP_0013_F | CCGCGAAGAGTACAACATCG | RT-qPCR of PP_0013 (gyrB) |

| qPP_0013_R | ACGGAAGAAGAAGGTCAGCA | RT-qPCR of PP_0013 (gyrB) |

In vitro Nucleic Acid Techniques

Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Qiagen spin miniprep kit. For DNA digestion, the manufacturer’s instructions were followed (New England Biolabs and Roche). Separated DNA fragments were recovered from agarose using the Qiagen gel extraction kit. Ligation reactions were performed as described in Sambrook et al. (1989). Competent cells were prepared using calcium chloride and transformations were performed by standard protocols (Sambrook et al., 1989). Phusion® high fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used in the amplification of PCR fragments for cloning.

Collection of Maize Root Exudates

Corn seeds (Zea mays var. Girona) were purchased from Fitó S.A. (Barcelona, Spain). The collection of MRE was carried out as previously indicated (Matilla et al., 2011). Briefly, maize seeds were rinsed and hydrated with sterile deionized water, washed with 70% (v/v) ethanol for 10 min, then with 20% (v/v) bleach for 15 min, followed by thorough rinsing with sterile deionized water. Sterilized seeds were pre-germinated on PhytagelTM agar (Sigma-Aldrich) prepared at 0.3% (w/v) in Plant Nutrient Solution (2.5 mM Ca(NO3)2, 2.5 mM KNO3, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4) containing 0.5% (w/v) glucose, 6% (w/v) Fe-citrate, 0.25% (w/v) trace elements (Abril et al., 1989) and incubated at 30°C in the dark for 48 h. Sixteen germinated seeds were transferred into an axenic system with 450 ml of sterile water and allowed to grow at room temperature. After 8 days, the water containing root exudates was collected and vacuum filtrated (0.45 μm cut-off). The resulting solution may also contain non-exuded metabolites derived for example from cell debris or released from root branching points. An aliquot was taken and spread onto solid LB media to check for contamination. Maize root exudates were aliquoted, freeze-dried and stored at -80°C. Before use, the lyophilized exudates were resuspended in sterile water at a 100x concentration (with respect to the 450 ml recipient), centrifuged at 5,000 ×g for 10 min and filter-sterilized. MRE at 0.1×, 1×, and 10× concentrations correspond to 0.023, 0.23, and 2.3 g/l.

Analysis of Root Exudates by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

Ten mg of freeze-dried MRE were resuspended in 120 μl methanol containing 0.2 mg/ml ribitol as internal standard. The solution was dried under nitrogen and derivatized by the addition of 60 μl pyridine containing 20 mg/ml methoxyamine. After brief vortexing, the resulting solution was incubated at 70°C for 120 min. After cooling and a brief centrifugation at 1000 ×g, 100 μl of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide with 1% (v/v) of the silylation agent trimethylchlorosilane were added and incubated at 70°C for 30 min. Once cooled down, 1 μl samples were injected at 230°C into a 450-GC 240 MS (Varian) Gas chromatography-mass spectrometer using the split mode (100:1). The He carrier gas flow was at 1 ml/min and the capillary chromatography column DB-5MS UI 30 mm × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm (Agilent Technologies) was used. Column oven ramp was set as follows: 70°C (5 min), to 245°C at 5°C/min, to 310°C at 20°C/min, 310°C (1 min). Electron Impact Ionization was at 70 eV and detection was carried out in Full Scan mode with acquisition between 50 and 600 m/z. Compound identification was achieved using the NIST-08 Standard reference database1 and data comparison with compound standards.

Determination of Chemoreceptor Gene Transcript Levels

Overnight cultures of P. putida KT2440 were used to inoculate flasks containing 20 ml M9 medium containing 10 mM glucose to an OD600 = 0.05. At an OD600 = 0.5, MRE were supplemented from concentrated stock solutions to final concentrations of 0.1×, 1×, and 10×; in parallel a control was supplemented with sterile water. Samples were taken before and 15, 30, and 45 min after root exudate addition. For the determination of gene transcript levels in the presence of one or two chemoeffectors, the same protocol was used, except that ligand solutions to a final concentration of 1 mM were added. RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses were performed as described previously (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). Briefly, RNA was extracted using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion). The extracted RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng RNA using the SuperScriptTM II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and 200 ng of random hexamer primers (Roche). RNA samples not treated with reverse transcriptase were used as negative RT controls. Quantitative PCRs were performed using the iQTM SYBR® Green supermix (Bio-Rad) and a MyiQTM thermocycler (Bio-Rad). PCR reactions contained 7.5 μl of 2× SYBR Green supermix, 500 nM of each primer and 1 μl of cDNA in a final volume of 15 μl. All PCR reactions were performed in duplicate. The PCR protocol used was as follows: 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C (10 s) and 60°C (30 s) and melting curve analysis from 55 to 95°C, with an increment of 0.5°C/10 s. The primers were designed using the Primer3 Plus software (Untergasser et al., 2012) and are listed in Table 3. Standard curves for each primer pair were generated with serial dilutions of genomic DNA and cDNA to determine PCR efficiency and each product was verified by melting curve analysis. The transcript level data were normalized to that of the reference gene rpoD and relative to the control sample using the Bio-Rad iQ5 software. Previous studies have validated rpoD as a suitable reference gene in pseudomonads (Savli et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2009). Transcript levels were determined using the relative quantity (ddCt) analysis method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Data are the means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses (t-test) were performed using GraphPad software.

Growth Experiments in the Presence of Exudates

Pseudomonas putida KT2440 was grown overnight in M9 medium supplemented with 10 mM glucose. Subsequently, bacterial cultures were diluted into the same medium to an OD600 = 0.02 and MRE were added to final concentrations of 0.1×, 1×, and 10×. The same volume of sterile deionized water was added to control cultures. Growth kinetics was determined by following the OD600 in a Microbiological Growth Analyzer (Bioscreen, Helsinki, Finland) at 30°C. Data shown are means and standard deviation from three experiments conducted in triplicate.

Construction of pp4338 (cheA2) Mutant

The mutant defective in PP_4338 (cheA2) was constructed by homologous recombination using a derivative plasmid of the suicide vector pKNG101 (Kaniga et al., 1991). This plasmid, named pMAMV290 (Table 2), carried a mutant allele for the replacement of the gene in the chromosome and was transferred to P. putida KT2440R by triparental conjugation using E. coli CC118λpir and E. coli HB101 (pRK600) as helper. For the construction of the final mutant, sucrose was added to a final concentration of 10% (w/v) to select derivatives that had undergone a second cross-over event during marker exchange mutagenesis. The resulting mutants were confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing.

Quantitative Capillary Chemotaxis Assays Toward MRE

Overnight cultures of P. putida KT2440R strains were diluted to an OD660 of 0.075 in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 6 mg l-1 Fe-citrate, trace elements (Abril et al., 1989) and 10 mM sodium benzoate as carbon source, and grown at 30°C with orbital shaking (200 rpm). At an OD660 of ∼0.4, cultures were centrifuged at 1,700 ×g for 5 min and the resulting pellet was washed twice with chemotaxis buffer [50 mM potassium phosphate, 20 mM EDTA, 0.05% (v/v) glycerol, pH 7.0]. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in the same buffer, adjusted to an OD660 = 0.1 and 230 μl aliquots of the bacterial cultures were placed into 96-well plates. Subsequently, one-microliter capillary tubes (Microcaps, Drummond Scientific, Ref. P1424) were heat-sealed at one end and filled with either the chemotaxis buffer (negative control), different concentrations of MRE or 0.2% (w/v) casamino acids. The capillaries were immersed into the bacterial suspensions at its open end and after 30 min at room temperature; capillaries were removed from the bacterial suspensions, rinsed with sterile water and the content expelled into 1 ml of M9 minimal medium. Serial dilutions were plated onto M9 minimal medium supplemented with 15 mM glucose as carbon source. The number of colony forming units was determined after overnight incubation. In all cases, data were corrected with the number of cells that swam into buffer containing capillaries.

Competitive Root Colonization Assays

Maize seeds were sterilized, germinated and inoculated as described previously (Matilla et al., 2007). Briefly, sterile seeds were incubated at 30°C with a 5 × 106 CFU/ml 1:1 mixture of KT2440RTn7-Sm (wild type) and a mutant strain defective in the corresponding cheA gene for 30 min. Thereafter, seeds were rinsed with sterile deionized water and planted in 50 ml Sterilin tubes containing 40 g of sterile washed silica sand. Plants were maintained at 24°C with a daily light period of 16 h. After 6 days, bacterial cells were recovered from the rhizosphere. Briefly, plant roots were collected, shaken vigorously to discard loosely attached silica sand and introduced into 50 ml sterile tubes containing 10 ml of M9 salts medium (Sambrook et al., 1989) and 4 g of glass beads (3 mm of diameter). Tubes were vortexed for 1 min and serial dilutions were plated onto LB-agar medium supplemented with streptomycin or kanamycin to select the wt or the mutant strains, respectively.

Construction of Expression Plasmids for PP4888-LBD

The DNA fragments encoding the LBDs of PP4888 of P. putida KT2440 were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA and primers listed in Table 3. The resulting product was digested and cloned into the expression plasmid pET28b(+) to create pPP4888. These plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Overexpression and Purification of Proteins

The different recombinant ligand binding domains were expressed in E. coli and purified by metal affinity chromatography using standard conditions.

Thermal Shift Assays

Assays were performed as reported in Fernandez et al. (2018) using a final DIBOA concentration of 1 mM.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Experiments were conducted on a VP-microcalorimeter (Microcal, Amherst, MA, United States) at 15°C. PP4888-LBD was dialyzed into 20 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, pH 7.4, adjusted to 50 μM and titrated with 0.5 mM of DIBOA prepared in dialysis buffer.

Colony-Based c-di-GMP Reporter Assays

Fluorescence intensity analyses using the c-di-GMP biosensor pCdrA::gfpC were carried out to determine the intracellular levels of the second messenger c-di-GMP. To this end, the reporter plasmid pCdrA::gfpC was transformed into KT2440R strains by electroporation. Subsequently, overnight bacterial cultures of the strains to be tested were adjusted to an OD660 = 0.05 and 20 μl aliquots were placed onto LB-agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotics. Following incubation at 30°C for 48 h, fluorescence intensities were recorded using a Leica M165 FC stereomicroscope. Fluorescence was visualized employing a GFP filter set (emission/excitation filter 470/525 nm). Pictures were taken using Leica Application Suite software using different exposure times.

Biofilm Formation Assays

Biofilm assays in borosilicate glass tubes were carried out with bacterial cultures grown in LB medium. Overnight cultures were adjusted to an OD660 = 0.05 and borosilicate tubes containing 1 ml of these cultures were incubated at 30°C under orbital shaking (40 rpm) in a Stuart SB3 tube rotator (Cole-Parmer). At the indicated times, bacterial cultures were removed, tubes rinsed three times with water and biofilms stained with 3 ml of crystal violet (0.5%, w/v) for 15 min at room temperature. Staining solution was discarded and tubes were rinsed three times with water. Biofilm formation was quantified by solubilizing the dye with 70% (v/v) ethanol and measuring the absorbance at 540 nm.

Swimming Motility Assays

Overnight cultures were adjusted to an OD660 = 1 and 2 μl of these cultures were spotted onto LB-Difco agar (0.3% [w/v]) plates and incubated at 30°C.

Results

The Effect of Maize Root Exudates on Chemoreceptor Gene Transcript Levels

Root exudates were obtained from maize and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to get information mainly on their composition in primary metabolites (Supplementary Figure S2). Compounds detected are listed in Supplementary Table S1 and include different sugars, sugar acids, amino acids and organic acids (Supplementary Table S1). To assess the effect of MRE on chemoreceptor gene transcript levels, KT2440 was grown in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM glucose. At an OD660 of 0.5, MRE were added to the culture at three different concentrations: 1× corresponds to the MRE concentration in the 450 ml recipient that contained 16 germinated maize seedlings for 8 days (see section “Materials and Methods” for further details), whereas the 0.1× and 10× concentrations are 10-fold diluted or concentrated samples thereof. Chemoreceptor gene transcript levels were quantified prior and 15, 30, or 45 min after MRE addition. As a control, the transcript levels of the housekeeping gene gyrB were measured in parallel.

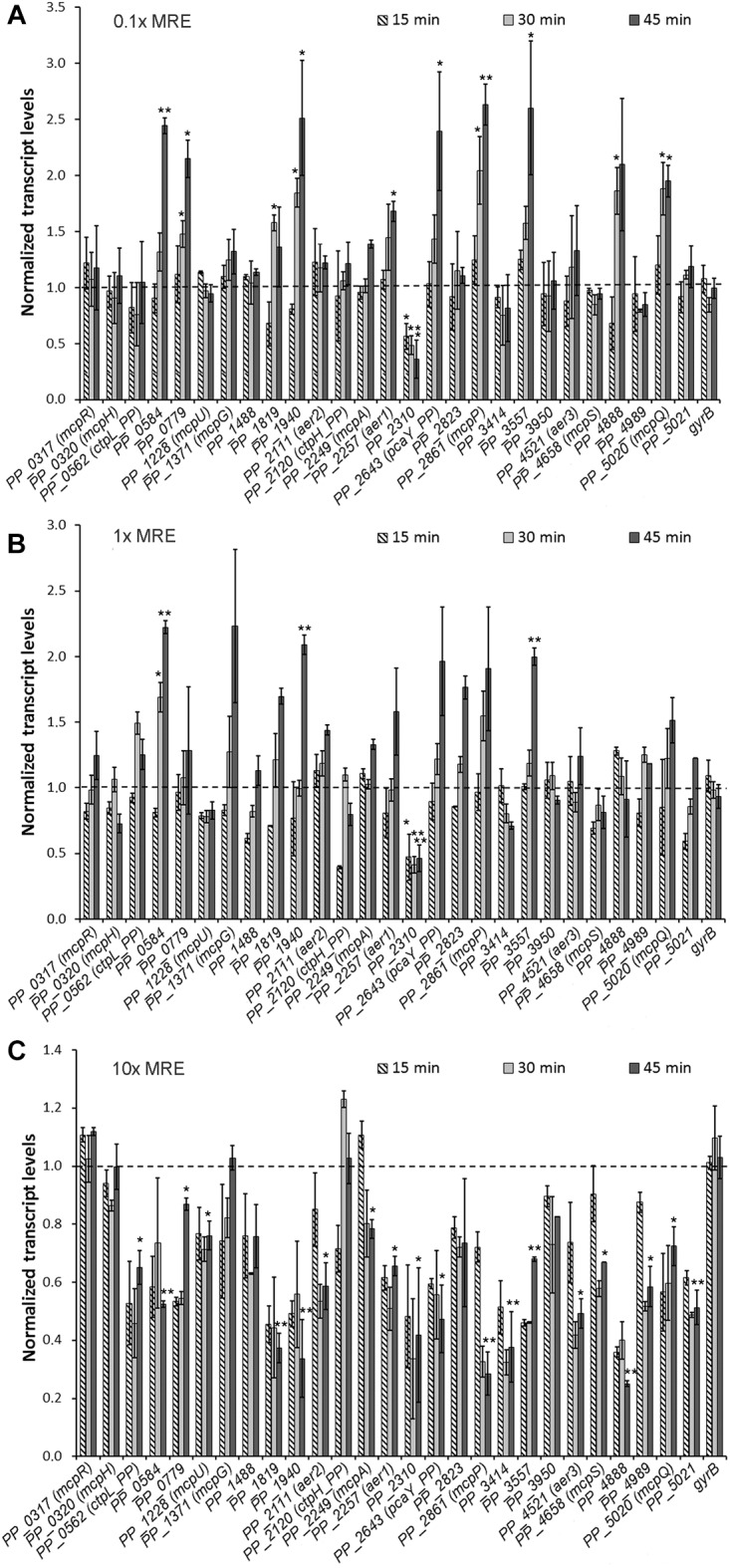

As shown in Figure 1A, an at least twofold induction of 8 chemoreceptor gene transcripts was noted at the 0.1× MRE concentration. The function of three of these receptors has been established since McpP, McpQ and PcaY_PP were found to bind and mediate chemoattraction to C2/3-carboxylic acids (Garcia et al., 2015), citrate (Martin-Mora et al., 2016) and C6 ring cyclic carboxylic acids (Fernandez et al., 2017), respectively. In the case of McpP and PcaY_PP, previous studies have shown that the cognate chemoeffectors increase chemoreceptor gene transcript levels, whereas citrate had no effect on mcpQ transcript levels (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). Another chemoreceptor gene induced by 0.1× MRE was PP_4888 (Figure 1A), which agrees with the study by Neal et al. (2012). The authors of this report show that MRE contain a significant amount of benzoxazinoids that attract P. putida chemotactically to the rhizosphere. To verify whether PP_4888 binds benzoxazinoids, we have cloned the DNA sequence encoding the LBD of this receptor into an expression plasmid and purified the recombinant protein from E. coli cultures. However, microcalorimetric titrations and thermal shift assays with DIBOA (2,4-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one) did not reveal binding indicating that PP_4888 does not bind this ligand directly. The remaining four chemoreceptor genes with at least twofold increased transcript levels, PP_0584, PP_0779, PP_1940, and PP_3557, are of unknown function. Additionally, two chemoreceptor genes, PP_1819 and PP_2257, showed a statistically significant increase in their transcript levels (Figure 1A). The function of PP_1819 remains unknown but PP_2257 is predicted to be an energy taxis receptor. Of note, exposition to 0.1× MRE reduced transcript levels of only one chemoreceptor gene, PP_2310 (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Transcript levels of the 27 chemoreceptor genes in response to different maize root exudate (MRE) concentrations. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 cells were grown to an OD600 = 0.5 in M9 medium containing 10 mM glucose as carbon source and MRE were added at a concentration of 0.1× (A), 1× (B), and 10× (C). Samples were taken 15, 30, and 45 min after MRE addition. Results were normalized with the reference gene rpoD and relative to the control sample (M9 + glucose medium). Data are the means and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments. The maximal standard deviations for the control measurements were of 0.16. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 (by Student’s t-test). For clarity reasons statistical relevance in (C) is only indicated for the 45 min measurement.

At a 1× MRE concentration a similar set of chemoreceptor genes showed increased transcript levels. However, the magnitude of induction was below that seen at the 0.1× concentration and a statistically significant increase was only observed for three receptors genes (Figure 1B). Interestingly, at a 10× MRE concentration, twenty chemoreceptor transcript levels showed statistically relevant reductions (Figure 1C). These include the ten receptors genes that were upregulated at the 0.1× MRE concentration.

On the other hand, genes encoding functionally annotated chemoreceptors including McpR for organic acids, McpH for purines, McpG for GABA and CtpH_PP for inorganic phosphate were little affected by 10× MRE (Figure 1C). Previous studies have shown that the cognate ligands do not alter mcpR and mcpG transcript levels whereas purines and inorganic phosphate either up- or downregulated, respectively, the transcript levels of their receptor genes (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). At all three MRE concentrations gene transcript levels of the gyrB control gene were unchanged.

Study of Chemoreceptor Gene Transcript Levels in the Presence of Ligand Mixtures

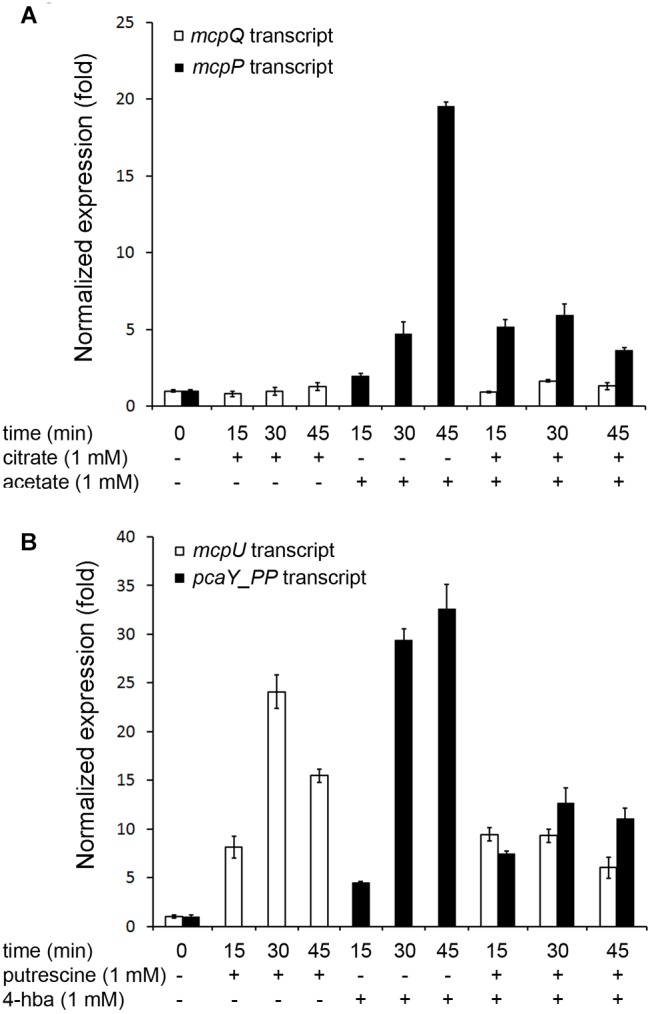

The magnitude of MRE mediated changes in chemoreceptor gene transcript levels were well below that observed in our previous study where we have evaluated the effect of 1 mM chemoeffectors on the transcript levels of their cognate chemoreceptor genes (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). For example, the cognate chemoeffectors acetate and 4-hydroxybenzoate enhanced mcpP and pcaY_PP transcript levels by factors of 22 and 35, respectively (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). This contrasts with the present data where MRE enhanced transcript levels of both chemoreceptors genes approximately 2.5-fold.

To cast light into this issue, we quantified the chemoreceptor gene transcript levels in cultures that contain either a single or two chemoeffectors, each at final concentrations of 1 mM. As shown in Figure 2A, the addition of 1 mM citrate did not increase mcpQ gene transcript levels, whereas in another culture the addition of 1 mM acetate enhanced mcpP transcript levels 20-fold, confirming previous studies (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). However, in a culture to which both, citrate and acetate have been added, the increase in mcpP transcript levels was only around sixfold, whereas that of mcpQ was unchanged. Additionally, in a similar experiment, changes in the transcript levels of mcpU and pcaY_PP by their cognate chemoeffectors was studied (Figure 2B). Putrescine and 4-hydroxybenzoate on their own (at 1 mM) increased mcpU and pcaY_PP transcript levels 24- and 32-fold, respectively. However, co-addition of both ligands (both at 1 mM) increased transcript levels of their receptors genes only 6–12-fold.

FIGURE 2.

Chemoreceptor gene transcript levels in absence and the presence of single or two simultaneously added chemoattractants. KT2440 cultures were grown to an OD600 = 0.5 (time 0) and a single or two chemoattractants were added to final concentrations of 1 mM for each compound. Samples were taken at the times indicated and the transcript levels of the chemoreceptor genes mcpQ and mcpP (A) or mcpU and pcaY_PP (B) were determined by RT-qPCR. 4-hba: 4-hydroxybenzoate. Data are means and standard deviations from three experiments.

Given the disparity in the changes of chemoreceptor genes transcript levels in the presence or absence of single or multiple chemoeffectors, our results indicate that there appears to be an intrinsic capacity of the cell to modulate receptor gene transcript levels; capacity that is shared among the individual receptors genes in the presence of multiple ligands.

Different Root Exudate Concentrations Do Not Alter Significantly Growth Kinetics

We were intrigued by the finding that at the 10× MRE concentration almost all chemoreceptor genes showed reduced transcript levels. MRE were found to contain significant amounts of benzoxazinoids like DIMBOA or DIBOA (Neal et al., 2012) that are plant secondary metabolites with a potent antibiotic activity (Wouters et al., 2016). To assess the effect of MRE on growth kinetics, we have recorded growth curves in M9 medium with 10 mM glucose as carbon source (control) and in this medium supplemented with different MRE concentrations. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3, the addition of 0.1× MRE did not alter growth kinetics significantly and only a slight reduction in the lag time was observed in the presence of 1 and 10× MRE. These differences in growth kinetics are thus unlikely to account for the differences in transcript levels seen at the 10× MRE concentration.

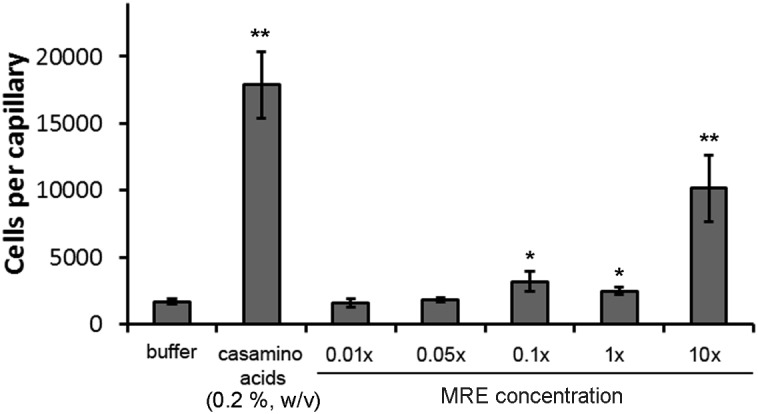

Chemotactic Responses Occur Only at Elevated Root Exudate Concentration

Interestingly, above data show that the most significant increase in chemoreceptor gene transcript levels occurred at the lowest MRE concentration. Since most of these receptors mediate chemotaxis, we assessed the chemotactic behavior of P. putida KT2440 to different MRE concentrations. To this end, we have carried out quantitative capillary chemotaxis assays, which is the traditional reference assay to quantify chemotaxis. In this assay, the chemoattractant is placed into a capillary that is then submerged into the bacterial suspension. After a contact time of 30 min, the capillaries are withdrawn, emptied and the number of colony forming units is determined. The expected strong chemotaxis was observed for a 0.2% (w/v) casamino acid solution that served as a positive control. No responses were noted for 0.01 and 0.05× MRE, whereas only minor chemotaxis was observed for the 0.1 and 1× concentrations (Figure 3). In contrast, MRE concentrations of 10× induced significant taxis (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Quantitative capillary chemotaxis assays of P. putida KT2440R to different maize root exudate concentrations. Chemotaxis to buffer and a 0.2% (w/v) casamino acid solution are shown as controls. Data are means and standard deviations from three individual experiments conducted in triplicates. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 (by Student’s t-test).

Effect of Root Exudates on c-di-GMP Levels, Biofilm Formation and Swimming Motility

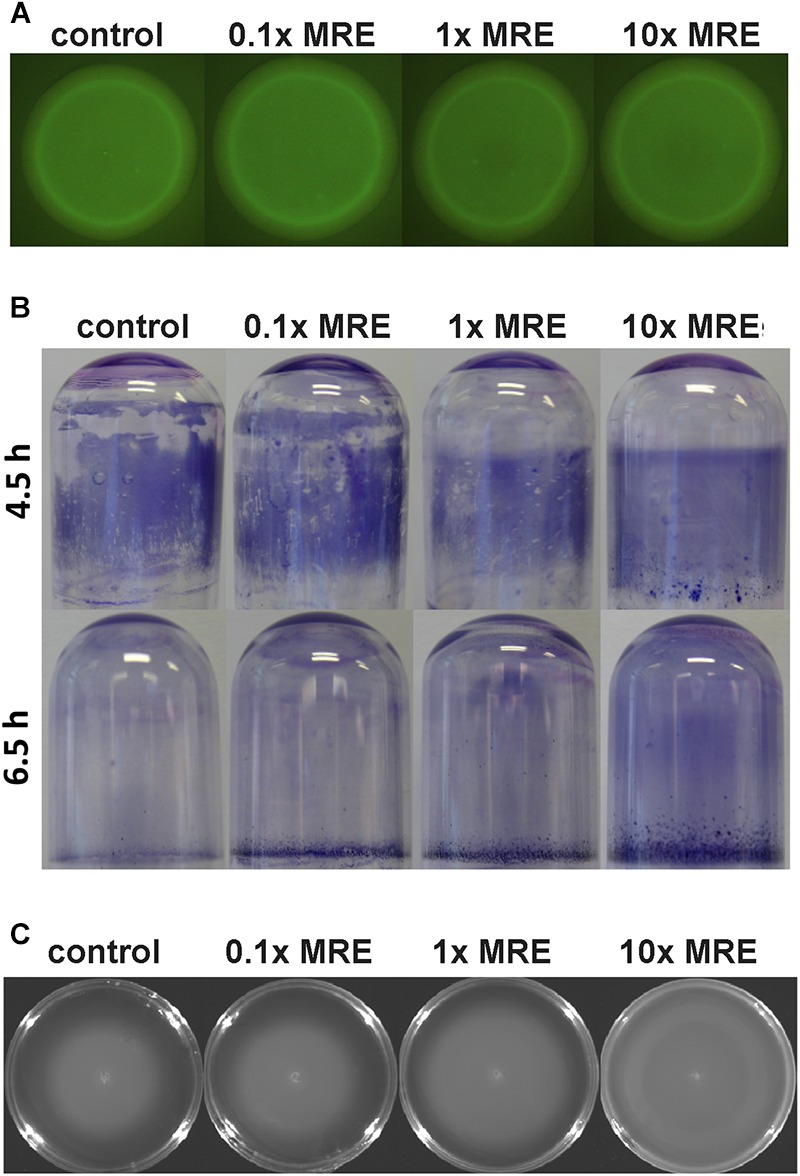

We conducted a number of studies to characterize the effect of MRE on different aspects of bacterial physiology. In all experiments cells were cultured in conditions that have been used for the quantification of chemoreceptor transcript levels, namely in minimal medium with glucose as carbon source in the absence and presence of different MRE concentrations. As mentioned above, a reduction of most chemoreceptor gene transcripts was observed at a 10x MRE concentration, suggesting that this may be due to a general regulatory mechanism. To assess whether this reduction may be caused by an alteration in the c-di-GMP levels, the plasmid pCdrA::gfpC harboring a c-di-GMP biosensor was introduced into P. putida KT2440 that was grown on plates containing different MRE concentrations. Since the output of this biosensor is the synthesis of the green fluorescent protein, individual colonies were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. However, as shown in Figure 4A, the exposure of the bacterium to different MRE concentrations did not result in significant changes in the c-di-GMP level.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of different root exudate concentrations on c-di-GMP levels, biofilm formation and motility of P. putida KT2440R. Cells were grown as liquid cultures (B) or on agar plates (A,C) in minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM glucose in the absence and presence of different MRE concentrations, which are the same conditions as used for RT-qPCR studies. (A) Fluorescence intensity of colonies harboring the c-di-GMP biosensor plasmid pCdrA::gfpC. (B) Biofilm formation on borosilicate tubes during growth with orbital shaking at 40 r.p.m. (C) Swimming motility after an 16 h incubation at 30°C. Each of these assays was conducted three times and representative images are shown.

Subsequent studies were aimed at elucidating the effect of different MRE concentrations on biofilm formation and dispersal. Biofilms were grown in borosilicate glass tubes under constant shaking. We noted that the biofilm formed in the presence of MRE was more homogeneous and more tightly attached to the glass surface (Figure 4B). This tightness of association was also reflected in a significant delay of biofilm dispersion with increasing MRE concentrations (Figure 4B). In subsequent experiments the swimming motility was assessed on 0.3% (w/v) agar plates containing different MRE concentrations. As shown in Figure 4C an increase in bacterial motility was observed with increasing MRE concentration.

Involvement of Different Chemosensory Pathways in Chemotaxis to Root Exudates

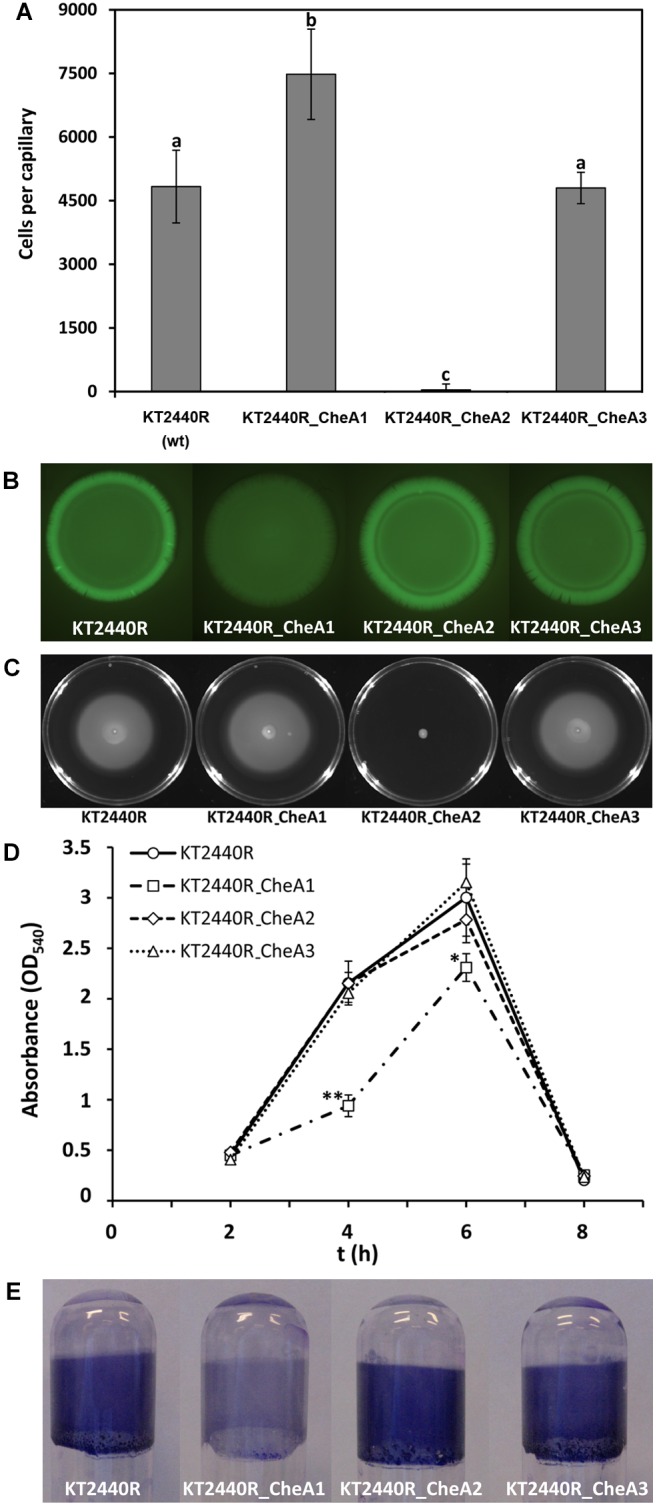

KT2440 has three CheA paralogs (Supplementary Figure S1) that are likely to form part of three pathways. To investigate the role of these three potential pathways in the chemotaxis to MRE, quantitative capillary chemotaxis assays to 10× MRE were conducted using mutants of cheA1, cheA2, and cheA3. As shown in Figure 5A, mutation in cheA1 increased the magnitude of chemotaxis, whereas mutation of cheA2 abolished chemotaxis, which is consistent with the notion the CheA2 forms part of the che chemotaxis pathway. Chemotaxis of the cheA3 mutant was indistinguishable from that of the wt strain.

FIGURE 5.

Functional analyses of the three CheA paralogs in P. putida KT2440. (A) Quantitative capillary chemotaxis assays to 10× MRE. Data were corrected with the number of cells that swam into buffer containing capillaries (from left to right, 1960 ± 339; 2093 ± 191; 2133 ± 280; 1980 ± 254). Data are the means and standard deviations from three biological replicates conducted in triplicate. Bars with the same letter are not significantly different (P-value < 0.05; by Student’s t-test). (B) Fluorescence intensity of P. putida KT2440R strains harboring the c-di-GMP biosensor plasmid pCdrA::gfpC. Experiments were conducted on LB agar plates. The assays were repeated three times and representative results are shown. (C) Swim plate motility assays. Shown is a representative experiment. Means and standard deviations of halo diameters from three biological replicates are shown in Supplementary Figure S6. (D) Quantification of biofilms stained with crystal violet. Data are means and standard deviations of three biological replicates. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, Student’s t-test of KT2440R_CheA1 with respect to the wt strain. (E) Biofilm formation in borosilicate glass tubes after 4 h of growth in LB medium with orbital shaking.

To assess whether this increase in chemotaxis in the cheA1 mutant is due to changes in the c-di-GMP levels, plasmid pCdrA::gfpC was introduced into the wt and the three cheA mutants and the resulting strains were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 5B, c-di-GMP levels were significantly reduced in the cheA1 mutant, whereas those of the other two cheA mutants were comparable to the wt. In a number of bacteria including KT2440 it has been shown that low c-di-GMP levels correlate with an increase in motility (Matilla et al., 2011; Romling et al., 2013). Therefore, the reduction in the c-di-GMP levels is likely to account for the slight, but reproducible increase in swimming motility observed for the cheA1 mutant (Figure 5C). We have subsequently investigated the contribution of the three CheA paralogs to biofilm formation. The kinetics of biofilm formation of the cheA1 mutant was distinct from that of the other strains, since this mutant formed significantly less biofilm after 4 and 6 h (Figure 5D). This difference was particularly pronounced after 4 h (Figure 5E). These data suggest the existence of functional wsp_PP and che_PP pathways, of which the latter is involved in root exudate chemotaxis.

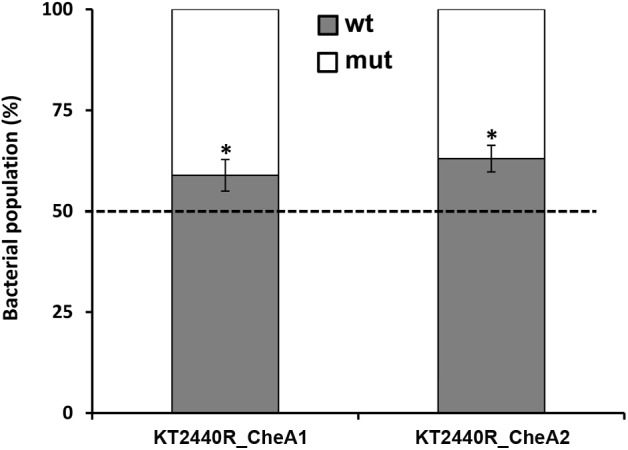

Involvement of Different Pathways in the Competitive Colonization of Maize Roots

It was shown previously that a mutant in cheA3 (PP_4988) exhibited reduced competitive colonization fitness to colonize maize roots as compared to the wt strain (Matilla et al., 2007). To determine the role of the remaining two pathways in the root colonization ability of KT2440, we have conducted competitive root colonization assays with mutants in cheA1 and cheA2 with the wt strain. Initial control experiments showed that the different strains showed similar growth kinetics (Supplementary Figure S4). In these assays equal amounts of wt and mutant strains with different antibiotics susceptibilities are used to inoculate maize roots. Supplementary Figure S5 shows another control experiment illustrating that the bacterial mixtures used for inoculation indeed contain the same amount of wt and mutant strains. Six days following inoculation bacteria are recovered and identified by plating out on media containing different antibiotics. As shown in Figure 6, both mutants were slightly less competitive in colonizing maize roots indicating that the che_PP as well as wsp_PP pathways play significant roles in root colonization.

FIGURE 6.

Competitive root colonization of Pseudomonas putida KT2440RTn7-Sm and mutants in different cheA genes. Shown is the relative abundance of mutant and wild type strains recovered from the rhizosphere of maize plants. Proportion of wild type and mutant strains in the initial inocula was 50 ± 3% (Supplementary Figure S5). Data are the means and standard deviations of six plants. ∗P < 0.01, Student’s t-test of mutant strains with respect to the wt strain.

Discussion

Using P. putida KT2440 as model bacterium, we present a study of the effect of root exudates on the transcript levels of the whole repertoire of chemoreceptor genes of a bacterium. Whereas at a distance to the root, exudates enhance chemoreceptor transcript levels promoting in turn chemotaxis, this process is reversed in root vicinity, where the necessity of root chemotaxis may be minor. A major conclusion of this work is that there is a temporal dimension to the effect of root exudates in the rhizosphere that has to be taken into account in studies to investigate plant–bacteria interaction. There are a number of studies that have investigated the impact of root exudates on the transcript levels of chemotaxis and motility genes (de Weert et al., 2002; Oku et al., 2012; Webb et al., 2016). However, data reported are contrasting, which is best illustrated by research on the influence of MRE on the gene transcript levels of two very similar plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, namely Bacillus atrophaeus UCMB-5137 and B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Whereas chemotaxis and motility genes were downregulated by MRE in the former strain (Mwita et al., 2016), they were upregulated in the latter strain (Fan et al., 2012).

What are thus the mechanisms responsible for these alterations in transcript levels? A significant number of chemoeffectors were shown to increase transcript levels of their cognate chemoreceptors, whereas a reduction was solely observed for the inorganic phosphate responsive receptors (Lopez-Farfan et al., 2017). It can thus be hypothesized that part of the increases observed at low MRE are due to the action of cognate ligands. However, the fact that almost all chemoreceptor transcripts were reduced at high MRE concentration suggests the existence of a more general mechanism, which may potentially be linked to the MRE induced changes in biofilm formation (Figure 4B). In accordance with this, previous results in our group established a link between the absence of chemotaxis and biofilm formation since the mutation of specific chemoreceptor genes resulted in an increased biofilm formation by KT2440 (Corral-Lugo et al., 2016). The second messenger c-di-GMP is the key determinant to define the balance between planktonic and sessile lifestyles (Romling et al., 2013) and in KT2440 it was found to enhance biofilm formation (Matilla et al., 2011; Ramos-Gonzalez et al., 2016). Remarkably, several studies have revealed that this second messenger can interfere with chemotactic processes, for example, by modulating the methylation state of chemoreceptors (Xu et al., 2016; Nesper et al., 2017) or by increasing swimming velocity through direct binding to chemoreceptor proteins (Russell et al., 2013). Therefore, we hypothesized that the general mechanism that modulates chemoreceptor transcripts levels may be based on alterations of the c-di-GMP level. However, our experiments with a c-di-GMP biosensor did not provide any evidence for MRE mediated changes in the level of this second messenger (Figure 4A) and further research is thus necessary to decipher the molecular mechanisms.

KT2440 has three paralogs of most chemosensory signaling proteins (Supplementary Figure S1), which is consistent with the notion that the 27 chemoreceptors feed into three different pathways, in a way comparable to that in P. aeruginosa (Ortega et al., 2017). Inactivation of the cheA2 gene abolished chemotaxis to MRE (Figure 5A), which agrees with the finding that the cheR2 mutant was also largely impaired in chemotaxis (Garcia-Fontana et al., 2013). Both proteins thus form part of a chemotaxis pathway similar to the P. aeruginosa che chemotaxis pathway (Ortega et al., 2017). In contrast, inactivation of cheA1 reduces c-di-GMP levels and increased chemotaxis to MRE (Figure 5A,B), which is likely due to the slight but reproducible increase in motility of this mutant (Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure S6). This mutant was also largely impaired in biofilm formation (Figure 5D,E), and a similar phenotype has been observed previously for the cheR2 mutant (Garcia-Fontana et al., 2013). These observations and the similarity of the corresponding gene cluster to P. aeruginosa indicates that both proteins form part of a signaling cascade homologous to the wsp pathway (Hickman et al., 2005). The output of this pathway is not directly related to chemotaxis but consists in a modulation of c-di-GMP levels potentially incorporating signals that stimulate the chemoreceptor PP1488 (homologous to P. aeruginosa WspA) (Hickman et al., 2005; O’Connor et al., 2012). Taken together, data indicate the existence of functional che and wsp pathways in KT2440. Importantly, signaling through both pathways is important for efficient root colonization since for both cheA mutants a discrete but reproducible reduction in competitive root colonization was observed (Figure 6). This suggests that chemotaxis to root exudates as well as an adjustment of c-di-GMP levels are two different, but interconnected processes that are required for efficient root colonization. Taken together, this work provides insight into regulatory mechanisms that occur in the rhizosphere. Future work will show whether the observed, dose-dependent effect of root exudates is also common to other rhizobacteria.

Author Contributions

DL-F, JR-D, and MM conducted the research and analyzed the data. MM and TK planned the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Dieter Sicker (Institut für Organische Chemie, Universität Leipzig, Germany) for the generous gift of DIBOA. We thank Dr. Rafael Nuñez Gomez from the Scientific Instrumentation Service of the EEZ for conducting GC-MS experiments.

Funding. This work was supported by FEDER funds and Fondo Social Europeo through grants to TK from the Junta de Andalucía (Grant CVI-7335) and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Grants BIO2013-42297 and BIO2016-76779-P).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00078/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abril M. A., Michan C., Timmis K. N., Ramos J. L. (1989). Regulator and enzyme specificities of the TOL plasmid-encoded upper pathway for degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons and expansion of the substrate range of the pathway. J. Bacteriol. 171 6782–6790. 10.1128/jb.171.12.6782-6790.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre G., Greer-Phillips S., Zhulin I. B. (2004). Ecological role of energy taxis in microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28 113–126. 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard-Massicotte R., Tessier L., Lecuyer F., Lakshmanan V., Lucier J. F., Garneau D., et al. (2016). Bacillus subtilis early colonization of arabidopsis thaliana roots involves multiple chemotaxis receptors. mBio 7:e01664-16. 10.1128/mBio.01664-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badri D. V., Vivanco J. M. (2009). Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 32 666–681. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdasarian M., Lurz R., Ruckert B., Franklin F. C., Bagdasarian M. M., Frey J., et al. (1981). Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene 16 237–247. 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90080-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda E., van Heck R. G., Lopez-Sanchez M. J., Cruveiller S., Barbe V., Fraser C., et al. (2016). The revisited genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 enlightens its value as a robust metabolic chassis. Environ. Microbiol. 18 3403–3424. 10.1111/1462-2920.13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal P., Allsopp L. P., Filloux A., Llamas M. A. (2017). The Pseudomonas putida T6SS is a plant warden against phytopathogens. ISME J. 11 972–987. 10.1038/ismej.2016.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer H. W., Roulland-Dussoix D. (1969). A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41 459–472. 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhais L. C., Dennis P. G., Fedoseyenko D., Hajirezaei M. R., Borriss R., von Wirén N. (2011). Root exudation of sugars, amino acids, and organic acids by maize as affected by nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and iron deficiency. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 174:e68555 10.1002/jpln.201000085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q., Amemiya T., Liu J., Xu X., Rajendran N., Itoh K. (2009). Identification and validation of suitable reference genes for quantitative expression of xylA and xylE genes in Pseudomonas putida mt-2. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 107 210–214. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2008.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Lugo A., de la Torre J., Matilla M. A., Fernandez M., Morel B., Espinosa-Urgel M., et al. (2016). Assessment of the contribution of chemoreceptor-based signaling to biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 18 3355–3372. 10.1111/1462-2920.13170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Lugo A., Matilla M. A., Martín-Mora D., Silva Jiménez H., Mesa Torres N., Kato J., et al. (2018). High-affinity chemotaxis to histamine mediated by the TlpQ chemoreceptor of the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 9:e01894-18. 10.1128/mBio.01894-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Lima L., Lopes Olivares F., Rodrigues de Oliveira R., Garcia Vega M. R., Oliveira Aguiar N., Pasqualoto Canellas L. (2014). Root exudate profiling of maize seedlings inoculated with Herbaspirillum seropedicae and humic acids. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agricult. 1 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- de Weert S., Vermeiren H., Mulders I. H., Kuiper I., Hendrickx N., Bloemberg G. V., et al. (2002). Flagella-driven chemotaxis towards exudate components is an important trait for tomato root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 15 1173–1180. 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.11.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis J. J., Zylstra G. J. (1998). Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 2710–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque E., Molina-Henares A. J., De la Torre Zúñiga J., Molina-Henares M. A., del Castillo-Santaella T., Lam J., et al. (2007). “Towards a genome-wide mutant library of Pseudomonas putida strain KT2440,” in Pseudomonas: AModel System in Biology, eds Ramos J. L., Filloux A. (Dorchester: Springer; ), 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Urgel M., Kolter R., Ramos J. L. (2002). Root colonization by Pseudomonas putida: love at first sight. Microbiology 148(Pt 2), 341–343. 10.1099/00221287-148-2-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Urgel M., Ramos J. L. (2004). Cell density-dependent gene contributes to efficient seed colonization by Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 5190–5198. 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5190-5198.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan B., Carvalhais L. C., Becker A., Fedoseyenko D., von Wiren N., Borriss R. (2012). Transcriptomic profiling of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 in response to maize root exudates. BMC Microbiol. 12:116. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H., Zhang N., Du W., Zhang H., Liu Y., Fu R., et al. (2018). Identification of chemotaxis compounds in root exudates and their sensing chemoreceptors in plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 31 995–1005. 10.1094/MPMI-01-18-0003-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M., Matilla M. A., Ortega A., Krell T. (2017). Metabolic value chemoattractants are preferentially recognized at broad ligand range chemoreceptor of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Front. Microbiol. 8:990. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M., Morel B., Corral-Lugo A., Krell T. (2016). Identification of a chemoreceptor that specifically mediates chemotaxis toward metabolizable purine derivatives. Mol. Microbiol. 99 34–42. 10.1111/mmi.13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M., Ortega A., Rico-Jimenez M., Martin-Mora D., Daddaoua A., Matilla M. A., et al. (2018). High-throughput screening to identify chemoreceptor ligands. Methods Mol. Biol. 1729 291–301. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7577-8-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan T. M., Kunkel B., De Vos G. F., Signer E. R. (1986). Second symbiotic megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti carrying exopolysaccharide and thiamine synthesis genes. J. Bacteriol. 167 66–72. 10.1128/jb.167.1.66-72.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin M. Y. (2005). A census of membrane-bound and intracellular signal transduction proteins in bacteria: bacterial IQ, extroverts and introverts. BMC Microbiol. 5:35. 10.1186/1471-2180-5-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia V., Reyes-Darias J. A., Martin-Mora D., Morel B., Matilla M. A., Krell T. (2015). Identification of a chemoreceptor for C2 and C3 carboxylic acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 5449–5457. 10.1128/AEM.01529-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fontana C., Reyes-Darias J. A., Munoz-Martinez F., Alfonso C., Morel B., Ramos J. L., et al. (2013). High specificity in CheR methyltransferase function: CheR2 of Pseudomonas putida is essential for chemotaxis, whereas CheR1 is involved in biofilm formation. J. Biol. Chem. 288 18987–18999. 10.1074/jbc.M113.472605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavira J. A., Ortega A., Martin-Mora D., Conejero-Muriel M. T., Corral-Lugo A., Morel B., et al. (2018). Structural basis for polyamine binding at the dCACHE domain of the McpU chemoreceptor from Pseudomonas putida. J. Mol. Biol. 430 1950–1963. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer R., Chen P. Y., Armitage J. P., Reinert G., Deane C. M. (2010). Deciphering chemotaxis pathways using cross species comparisons. BMC Syst. Biol. 4:3. 10.1186/1752-0509-4-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S., Mathesius U. (2012). The role of flavonoids in root-rhizosphere signalling: opportunities and challenges for improving plant-microbe interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 63 3429–3444. 10.1093/jxb/err430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelbauer G. L., Falke J. J., Parkinson J. S. (2008). Bacterial chemoreceptors: high-performance signaling in networked arrays. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33 9–19. 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero M., de Lorenzo V., Timmis K. N. (1990). Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172 6557–6567. 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman J. W., Tifrea D. F., Harwood C. S. (2005). A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 14422–14427. 10.1073/pnas.0507170102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Barbe V., Lee C. H., Vallenet D., Yu D. S., Choi S. H., et al. (2009). Genome sequences of Escherichia coli B strains REL606 and BL21(DE3). J. Mol. Biol. 394 644–652. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniga K., Delor I., Cornelis G. R. (1991). A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109 137–141. 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd P. S., Llugany M., Poschenrieder C., Gunse B., Barcelo J. (2001). The role of root exudates in aluminium resistance and silicon-induced amelioration of aluminium toxicity in three varieties of maize (Zea mays L.). J. Exp. Bot. 52 1339–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Hill D. S., Robertson G. T., Farris M. A., Roop R. M., et al. (1995). Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166 175–176. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraffczyk I., Trolldenier G., Beringer H. (1984). Soluble root exudates of maize: influence of potassium supply and rhizosphere microorganisms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 16 315–322. 10.1016/0038-0717(84)90025-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacal J., Alfonso C., Liu X., Parales R. E., Morel B., Conejero-Lara F., et al. (2010a). Identification of a chemoreceptor for tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates: differential chemotactic response towards receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 285 23126–23136. 10.1074/jbc.M110.110403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacal J., Garcia-Fontana C., Munoz-Martinez F., Ramos J. L., Krell T. (2010b). Sensing of environmental signals: classification of chemoreceptors according to the size of their ligand binding regions. Environ. Microbiol. 12 2873–2884. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacal J., Garcia-Fontana C., Callejo-Garcia C., Ramos J. L., Krell T. (2011). Physiologically relevant divalent cations modulate citrate recognition by the McpS chemoreceptor. J. Mol. Recognit. 24 378–385. 10.1002/jmr.1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub M. T., Goulian M. (2007). Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41 121–145. 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Farfan D., Reyes-Darias J. A., Krell T. (2017). The expression of many chemoreceptor genes depends on the cognate chemoeffector as well as on the growth medium and phase. Curr. Genet. 63 457–470. 10.1007/s00294-016-0646-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu R. A., Kootstra J. D., Nesteryuk V., Brunton C. N., Parales J. V., Ditty J. L., et al. (2015). Integration of chemotaxis, transport and catabolism in Pseudomonas putida and identification of the aromatic acid chemoreceptor PcaY. Mol. Microbiol. 96 134–147. 10.1111/mmi.12929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Mora D., Reyes-Darias J. A., Ortega A., Corral-Lugo A., Matilla M. A., Krell T. (2016). McpQ is a specific citrate chemoreceptor that responds preferentially to citrate/metal ion complexes. Environ. Microbiol. 18 3284–3295. 10.1111/1462-2920.13030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla M. A., Espinosa-Urgel M., Rodriguez-Herva J. J., Ramos J. L., Ramos-Gonzalez M. I. (2007). Genomic analysis reveals the major driving forces of bacterial life in the rhizosphere. Genome Biol. 8:R179. 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla M. A., Krell T. (2018). The effect of bacterial chemotaxis on host infection and pathogenicity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42:fux052. 10.1093/femsre/fux052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla M. A., Ramos J. L., Bakker P. A., Doornbos R., Badri D. V., Vivanco J. M., et al. (2010). Pseudomonas putida KT2440 causes induced systemic resistance and changes in Arabidopsis root exudation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2 381–388. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla M. A., Travieso M. L., Ramos J. L., Ramos-Gonzalez M. I. (2011). Cyclic diguanylate turnover mediated by the sole GGDEF/EAL response regulator in Pseudomonas putida: its role in the rhizosphere and an analysis of its target processes. Environ. Microbiol. 13 1745–1766. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwita L., Chan W. Y., Pretorius T., Lyantagaye S. L., Lapa S. V., Avdeeva L. V., et al. (2016). Gene expression regulation in the plant growth promoting Bacillus atrophaeus UCMB-5137 stimulated by maize root exudates. Gene 590 18–28. 10.1016/j.gene.2016.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa T. (2002). Travels of a Pseudomonas, from Japan around the world. Environ. Microbiol. 4 782–786. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal A. L., Ahmad S., Gordon-Weeks R., Ton J. (2012). Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS One 7:e35498. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesper J., Hug I., Kato S., Hee C. S., Habazettl J. M., Manfredi P., et al. (2017). Cyclic di-GMP differentially tunes a bacterial flagellar motor through a novel class of CheY-like regulators. eLife 6:e28842. 10.7554/eLife.28842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J. R., Kuwada N. J., Huangyutitham V., Wiggins P. A., Harwood C. S. (2012). Surface sensing and lateral subcellular localization of WspA, the receptor in a chemosensory-like system leading to c-di-GMP production. Mol. Microbiol. 86 720–729. 10.1111/mmi.12013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku S., Komatsu A., Tajima T., Nakashimada Y., Kato J. (2012). Identification of chemotaxis sensory proteins for amino acids in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 and their involvement in chemotaxis to tomato root exudate and root colonization. Microbes Environ. 27 462–469. 10.1264/jsme2.ME12005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega D. R., Fleetwood A. D., Krell T., Harwood C. S., Jensen G. J., Zhulin I. B. (2017). Assigning chemoreceptors to chemosensory pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 12809–12814. 10.1073/pnas.1708842114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parales R. E., Luu R. A., Chen G. Y., Liu X., Wu V., Lin P., et al. (2013). Pseudomonas putida F1 has multiple chemoreceptors with overlapping specificity for organic acids. Microbiology 159(Pt 6), 1086–1096. 10.1099/mic.0.065698-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parales R. E., Luu R. A., Hughes J. G., Ditty J. L. (2015). Bacterial chemotaxis to xenobiotic chemicals and naturally-occurring analogs. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 33 318–326. 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J. S., Hazelbauer G. L., Falke J. J. (2015). Signaling and sensory adaptation in Escherichia coli chemoreceptors: 2015 update. Trends Microbiol. 23 257–266. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriacq P., Williams A., Cotton A., McFarlane A. E., Rolfe S. A., Ton J. (2017). Metabolite profiling of non-sterile rhizosphere soil. Plant J. 92 147–162. 10.1111/tpj.13639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M., Zamioudis C., Berendsen R. L., Weller D. M., Van Wees S. C., Bakker P. A. (2014). Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 52 347–375. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Molina E., Reyes-Darias J. A., Lacal J., Ramos J. L., Garcia-Ruiz J. M., Gavira J. A., et al. (2012). Evidence for chemoreceptors with bimodular ligand-binding regions harboring two signal-binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 18926–18931. 10.1073/pnas.1201400109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Gonzalez M. I., Travieso M. L., Soriano M. I., Matilla M. A., Huertas-Rosales O., Barrientos-Moreno L., et al. (2016). Genetic dissection of the regulatory network associated with high c-di-GMP levels in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Front. Microbiol. 7:1093. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenhardt D., Heuer H., Heim S., Fernandez D. U., Strompl C., Moore E. R., et al. (2002). Pedigree and taxonomic credentials of Pseudomonas putida strain KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 4 912–915. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Darias J. A., Garcia V., Rico-Jimenez M., Corral-Lugo A., Lesouhaitier O., Juarez-Hernandez D., et al. (2015). Specific gamma-aminobutyrate chemotaxis in pseudomonads with different lifestyle. Mol. Microbiol. 97 488–501. 10.1111/mmi.13045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romling U., Galperin M. Y., Gomelsky M. (2013). Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77 1–52. 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. H., Bible A. N., Fang X., Gooding J. R., Campagna S. R., Gomelsky M., et al. (2013). Integration of the second messenger c-di-GMP into the chemotactic signaling pathway. mBio 4:e00001-13. 10.1128/mBio.00001-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybtke M. T., Borlee B. R., Murakami K., Irie Y., Hentzer M., Nielsen T. E., et al. (2012). Fluorescence-based reporter for gauging cyclic di-GMP levels in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 5060–5069. 10.1128/AEM.00414-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn New York, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro I., Parales R. E., Krell T., Hill J. E. (2015). Pseudomonas chemotaxis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39 17–46. 10.1111/1574-6976.12081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarand I., Osterberg S., Holmqvist S., Holmfeldt P., Skarfstad E., Parales R. E., et al. (2008). Metabolism-dependent taxis towards (methyl)phenols is coupled through the most abundant of three polar localized Aer-like proteins of Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 10 1320–1334. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savli H., Karadenizli A., Kolayli F., Gundes S., Ozbek U., Vahaboglu H. (2003). Expression stability of six housekeeping genes: a proposal for resistance gene quantification studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. J. Med. Microbiol. 52(Pt 5), 403–408. 10.1099/jmm.0.05132-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf B. E., Hynes M. F., Alexandre G. M. (2016). Chemotaxis signaling systems in model beneficial plant-bacteria associations. Plant Mol. Biol. 90 549–559. 10.1007/s11103-016-0432-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., Remm M., et al. (2012). Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e115. 10.1093/nar/gks596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam N. M., Bouwmeester H. J. (2016). Metabolomics in the rhizosphere: tapping into belowground chemical communication. Trends Plant Sci. 21 256–265. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vejan P., Abdullah R., Khadiran T., Ismail S., Nasrulhaq Boyce A. (2016). Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in agricultural sustainability-a review. Molecules 21:E573. 10.3390/molecules21050573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B. A., Helm R. F., Scharf B. E. (2016). Contribution of individual chemoreceptors to Sinorhizobium meliloti chemotaxis towards amino acids of host and nonhost seed exudates. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 29 231–239. 10.1094/MPMI-12-15-0264-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch C. B., Leech A. J., Young M. D., Kennedy D., Sargent J. L., Bertrand J. J., et al. (2004). Characterization of a complex chemosensory signal transduction system which controls twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 52 873–893. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock D. M., Crowther P. J., Doherty J., Jefferson S., DeCruz E., Noyer-Weidner M., et al. (1989). Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 3469–3478. 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters F. C., Blanchette B., Gershenzon J., Vassao D. G. (2016). Plant defense and herbivore counter-defense: benzoxazinoids and insect herbivores. Phytochem. Rev. 15 1127–1151. 10.1007/s11101-016-9481-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Kato J., Kuroda A., Ikeda T., Takiguchi N., Ohtake H. (2000). Identification and characterization of two chemotactic transducers for inorganic phosphate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182 3400–3404. 10.1128/JB.182.12.3400-3404.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuichet K., Zhulin I. B. (2010). Origins and diversification of a complex signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Sci. Signal. 3:ra50. 10.1126/scisignal.2000724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Xin L., Zeng Y., Yam J. K., Ding Y., Venkataramani P., et al. (2016). A cyclic di-GMP-binding adaptor protein interacts with a chemotaxis methyltransferase to control flagellar motor switching. Sci. Signal. 9:ra102. 10.1126/scisignal.aaf7584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.