Abstract

Inflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of a number of psychiatric and neurological disorders. Soluble epoxide hydrolases (sEH), enzymes present in all living organisms, metabolize epoxy fatty acids (EpFAs) to corresponding 1,2-diols by the addition of a molecule of water. Accumulating evidence suggests that sEH in the metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) plays a key role in inflammation. Preclinical studies demonstrated that protein expression of sEH in the prefrontal cortex, striatum, and hippocampus from mice with depression-like phenotype was higher than control mice. Furthermore, protein expression of sEH in the parietal cortex from patients with major depressive disorder was higher than controls. Interestingly, Ephx2 knock-out (KO) mice exhibit stress resilience after chronic social defeat stress. Furthermore, the sEH inhibitors have antidepressant effects in animal models of depression. In addition, pharmacological inhibition or gene KO of sEH protected against dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the striatum after repeated administration of MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Protein expression of sEH in the striatum from MPTP-treated mice was higher than control mice. A number of studies using postmortem brain samples showed that the deposition of protein aggregates of α-synuclein, termed Lewy bodies, is evident in multiple brain regions of patients from PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Moreover, the expression of the sEH protein in the striatum from patients with DLB was significantly higher compared with controls. Interestingly, there was a positive correlation between sEH expression and the ratio of phosphorylated α-synuclein to α-synuclein in the striatum. In the review, the author discusses the role of sEH in the metabolism of PUFAs in inflammation-related psychiatric and neurological disorders.

Keywords: α-synuclein, cytochrome P450, dementia of Lewy bodies, depression, epoxy fatty acids, inflammation, Parkinson’s disease, stress resilience

Introduction

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are generally considered to be necessary for maintaining normal physiology (Jump, 2002; Bazinet and Layé, 2014; Layé et al., 2018). PUFAs are known to regulate both the structure and the function of neurons, glial cells, and endothelial cells in the brain (Bazinet and Layé, 2014; Layé et al., 2018). Importantly, PUFAs need to be provided by the diet since they cannot be produced in mammals. There are two main families (ω-3 and ω-6) of PUFAs. Linoleic acid, the predominant plant-derived dietary ω-6 PUFA, is a precursor of arachidonic acid (ARA). α-linolenic acid, the predominant plant-derived dietary ω-3 PUFA, is a precursor of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

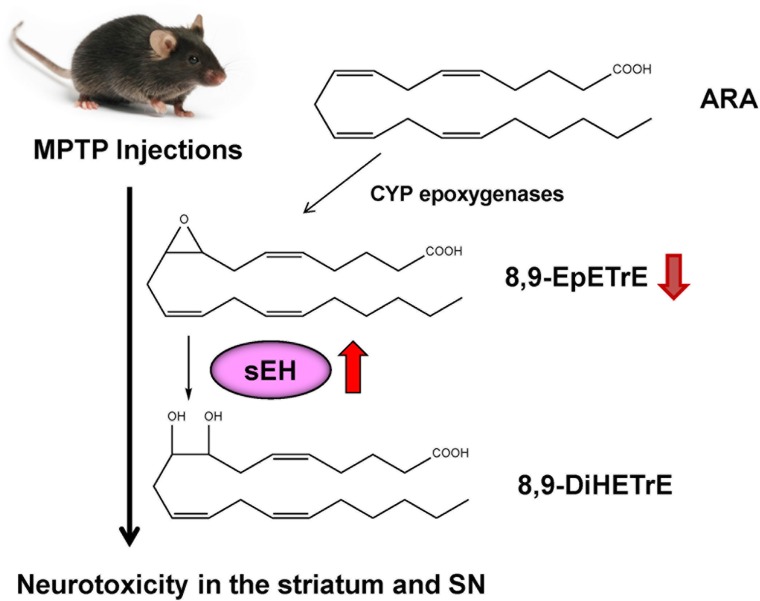

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are metabolized into bioactive derivatives by the main enzymes such as cyclooxygenases (COXs), lipoxygenases (LOXs), and cytochrome P450s (CYPs) (Imig and Hammock, 2009; Arnold et al., 2010; Imig, 2012, 2018; Morisseau and Hammock, 2013; Bazinet and Layé, 2014; Urquhart et al., 2015; Westphal et al., 2015; Figure 1). The COX pathway leads to the formation of prostaglandins, prostacyclines and thromboxanes, the LOX pathway leads to leukotrienes, lipoxins, and hydroxyl-eicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs). The CYP pathway leads to 20-HETE by CYP hydroxylases, and epoxy fatty acids (EpFAs) such as epoxy-eicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and epoxydocosapentaenoic acids (EDPs) by CYP epoxygenases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). PUFAs such as arachidonic acid (ARA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are converted to prostaglandins, prostacyclins, and thromboxanes by cyclooxygenase (COX). PUFAs are also converted to leukotrienes, lipoxins, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) by lipoxygenase (LOX). Moreover, PUFAs are converted to hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs), including 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE), and epoxy fatty acids (EpFAs), including epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and epoxydocosapentaenoic acids (EDPs), by cytochrome P450 (CYP) hydroxylases and CYP epoxygenases, respectively. EpFAs (e.g., EETs, EDPs) are converted to their corresponding 1,2-diols (e.g., dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs), dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acids [DiHDPAs]) by soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH). (modified from Morisseau and Hammock, 2013 and Hashimoto, 2016).

In the review, the author would like to discuss the role of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) in the CYP-mediated metabolism of PUFAs which might be involved in the pathogenesis of psychiatric and neurological disorders. Furthermore, we also refer to the clinical significance of sEH inhibitors for these disorders.

Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase in CYP System

The CYP system is a superfamily of enzymes, which are involved in the metabolism of exogenous and endogenous compounds. The CYP in the eicosanoid pathway was first described in 1980 and is comprised of two enzymatic pathways such as hydroxylases and epoxygenases. The CYP isoforms metabolize a number of ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs, including ARA, EPA and DHA into bioactive lipid mediators, termed eicosanoids (Imig and Hammock, 2009; Imig, 2012, 2018; Morisseau and Hammock, 2013; Urquhart et al., 2015; Westphal et al., 2015; Jamieson et al., 2017). The CYP system produces both the pro-inflammatory, terminally hydroxylated metabolite 20-HETE and the anti-inflammatory EpFAs, including EETs from ARA and EDPs from DHA (Figure 1).

In contrast, EpFAs such as EETs, and EDPs are rapidly metabolized by a number of pathways including the soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) (Imig and Hammock, 2009; Morisseau and Hammock, 2013). The sEH was first identified in the cytosolic fraction of mouse liver through its activity on epoxide containing substances such as juvenile hormone and lipid epoxides (Hammock et al., 1976; Gill and Hammock, 1980; Ota and Hammock, 1980). Human sEH is a 62 kDa enzyme composed of two domains separately by a short proline-rich linker (Harris and Hammock, 2013). The N-terminal domain has a phosphatase activity that hydrolyzes lipid phosphates, while the C-terminal domain has an epoxide hydrolase activity that converts epoxides to their corresponding diols (Newman et al., 2003). The human EPHX2 gene codes for the sEH protein is widely expressed in a number of tissues, including the liver, lungs, kidney, heart, brain, adrenals, spleen, intestines, urinary bladder, placenta, skin, mammary gland, testis, leukocytes, vascular endothelium, and smooth muscle. Interestingly, the sEH protein is most highly expressed in the liver and kidney (Gill and Hammock, 1980; Newman et al., 2005; Imig, 2012).

Accumulating evidence suggests that EETs, EDPs and some other EpFAs have potent anti-inflammatory properties (Wagner et al., 2014, 2017; López-Vicario et al., 2015) which are implicated in the pathogenesis of a number of psychiatric and neurological disorders (Denis et al., 2015; Hashimoto, 2015, 2016, 2018; Gumusoglu and Stevens, 2018; Polokowski et al., 2018).

Inflammation in Depression and sEH

Depression, one of the most common disorders in the world, is a major psychiatric disorder with a high rate of relapse. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 320 million individuals of all ages suffer from depression (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate inflammatory processes in the pathophysiology of depression and in the antidepressant actions of the certain compounds (Dantzer et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2009, 2017; Raison et al., 2010; Hashimoto, 2015, 2016, 2018; Mechawar and Savitz, 2016; Miller and Raison, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016a,b, 2017b,a). Meta-analysis showed higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood of drug-free or medicated depressed patients compared to healthy controls (Dowlati et al., 2010; Young et al., 2014; Haapakoski et al., 2015; Eyre et al., 2016; Köhler et al., 2018). Collectively, it is likely that inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology of depression.

Several reports using meta-analysis demonstrated that ω-3 PUFAs could reduce depressive symptoms beyond placebo (Lin et al., 2010, 2017; Sublette et al., 2011; Mello et al., 2014; Grosso et al., 2016; Hallahan et al., 2016; Mocking et al., 2016; Sarris et al., 2016; Bai et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2018). Dietary intake of ω-3 PUFAs is known to be associated with lower risk of depression. Importantly, EPA-rich ω-3 PUFAs could be recommended for the treatment of depression (Sublette et al., 2011; Mocking et al., 2016; Sarris et al., 2016). Importantly, brain EPA levels are 250-300-fold lower than DHA compared to about 4- (plasma), 5- (erythrocyte), 14- (liver), and 86-fold (heart) lower levels of EPA versus DHA (Chen and Bazinet, 2015; Dyall, 2015).

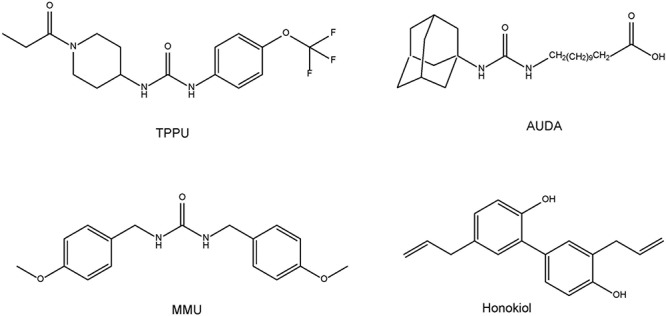

Given the role of inflammation in depression, it is likely that sEH might contribute to the pathophysiology of depression. A single injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is known to produce depression-like phenotypes in rodents after sickness behaviors (Dantzer et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2014, 2016a, 2017b; Ma et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). Ren et al. (2016) reported that the sEH inhibitor TPPU [1-(1-propionylpiperidin-4-yl)-3-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)urea] (Figure 2) conferred prophylactic and antidepressant effects in the LPS-induced inflammation model of depression while the current antidepressants showed no therapeutic effects in this model (Zhang et al., 2014). Chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) model of depression is widely used as an animal model of depression (Nestler and Hyman, 2010; Golden et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2015, 2017, 2018). Pretreatment with TPPU before social defeat stress showed resilience to CSDS. In addition, TPPU showed rapid antidepressant effects in susceptible mice after CSDS (Ren et al., 2016). Interestingly, the sEH KO mice showed stress resilience to repeated social defeat stress. Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor TrkB signaling in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of the KO mice might be responsible for stress resilience (Ren et al., 2016). Furthermore, repeated treatment with TPPU for 7 days increased interaction time of socially defeated mice in a CSDS model, and improvement by TPPU was blocked by TrkB antagonist K252a (Wu et al., 2017), suggesting a role of BDNF-TrkB signaling in TPPU’s beneficial effects. Interestingly, higher protein levels of sEH were shown in the brain regions of mice with a depression-like phenotype in the inflammation and CSDS models, suggesting that increased levels of sEH may play a role in depression-like phenotypes in rodents (Ren et al., 2016). We found higher sEH protein levels in the parietal cortex (Brodmann area 7) from patients with major depressive disorder, pointing to a possible role for increased sEH levels in depression (Ren et al., 2016). Taken together, this study highlights a key function for sEH in the pathophysiology of depression, and for its inhibitors as potential therapeutic or prophylactic drugs for depression (Hashimoto, 2016; Ren et al., 2016; Swardfager et al., 2018; Figure 3).

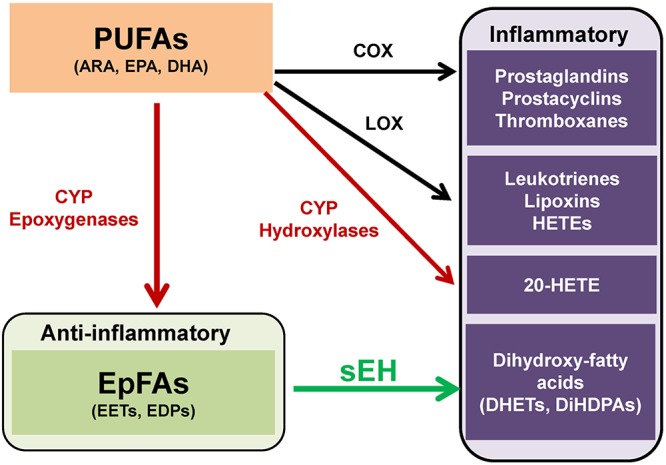

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of sEH inhibitors TPPU, AUDA, MMU, and honokiol.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism of the role of sEH in depression. Inflammation or stress can increase the expression of sEH in the brain, resulting in enhanced metabolism of anti-inflammatory PUFA epoxides (EpFAs). Subsequently, increased expression of sEH can decrease BDNF-TrkB signaling and synaptogenesis, leading to depressive symptoms. The sEH inhibitors may have antidepressant actions in depressed patients. (modified from Hashimoto, 2016).

A study using euthymic patients with a history of major depressive disorder with seasonal depression showed changes in CYP- and sEH-derived eicosanoids in patients with winter depression (Hennebelle et al., 2017). The ω-6 derived sEH product 12,13-DiHOME [12,13-dihydroxy-9-octadecenoic acid] increased in winter depression. Total 14,15-EpETE [14,15-epoxy-5Z,8Z,11Z,17Z-eicosatetraenoic acid], a sEH substrate, as well as sEH-derived free 14,15-DiHETrE [14,15-dihydroxy-5Z,8Z,11Z- eicosatrienoic acid], decreased during winter compared to summer-fall, while sEH-derived total 7,8-DiHDPE [7,8-dihydroxy-4Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z-docosapentaenoic acid], total 19,20-DiHDPE [19,20-dihydroxy-4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z-docosapentaenoic acid], and total 12,13-DiHOME [12,13-dihydroxy-9Z-octadecenoic acid] were increased during winter. These findings suggest that seasonal shifts in ω-6 and ω-3 PUFAs metabolism mediated by sEH may underlie inflammatory states in symptomatic depression with seasonal pattern (Hennebelle et al., 2017). Given the crucial role of sEH in the metabolism of ω-3 PUFAs, ω-3 PUFAs such as EPA in combination with a sEH inhibitor would be a novel therapeutic approach for depression (Figure 3).

Eating Disorders and ADHD

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious eating disorder characterized by the persistent restriction of energy intake, intense fear of gating weight, and distribution in self-perceived weight or shape. The Epoxide Hydrolase 2 (EPHX2) gene was found to harbor several common and rare risk variants for AN (Scott-Van Zeeland et al., 2014). Subsequently, the patients with AN show elevated plasma levels of ω-3 PUFAs (ARA, EPA, DHA) compared to controls (Shih et al., 2016). Interestingly, 15,16-DiHODE [15,16-dihydroxy-9Z,12Z-octadecadienoic acid]/15,16-EpODE [15,16-epoxy-9Z,12Z-octadecadienoic acid] ratio derived from ARA and 19,20-DiHDPE [19,20-dihydroxy-4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z- docosapentaenoic acid]/19,20-EpDPE [19,20-epoxy-4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z-docosapentaenoic acid] ratio derived from DHA in AN patients were higher than controls, suggesting a higher in vivo sEH activity, concentration, or efficiency in AN (Shih et al., 2016; Shih, 2017). These data suggest the role of EPHX2-associated eicosanoid dysregulations in AN. Collectively, sEH inhibitors might be potential therapeutic drugs for AN (Shih et al., 2016; Shih, 2017).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common psychiatric disorders affecting children. Symptoms of ADHD include inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. However, biological mechanisms underlying ADHD remain unknown. A meta-analysis shows that children and youth with ADHD have elevated ratios of both blood ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs compared to controls (LaChance et al., 2016), suggesting an elevated ω-6/ω-3, and more specifically ARA/EPA ratio may represent the underlying disturbance in essential PUFAs levels in patients with ADHD. A recent meta-analysis shows that children and adolescents with ADHD have lower levels of DHA, EPA, and total ω-3 PUFAs (Chang et al., 2018). Furthermore, supplementation of ω-3 PUFAs, particularly with high doses of EPA, was modestly effective in the treatment of ADHD (Bloch and Qawasmi, 2011; Chang et al., 2018). Collectively, it is of great interest to study whether blood levels of EpFAs and their corresponding diols are altered in the patients with ADHD. Furthermore, it is also interesting to investigate the role of sEH in the pathogenesis of ADHD since there are no reports showing the role of sEH in ADHD.

Inflammation in Parkinson’s Disease and sEH

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease. Although the precise pathogenesis of PD is unknown, the pathological hallmark of PD involves the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) (Kalia and Lang, 2015; Ascherio and Schwarzschild, 2016). In addition, the deposition of aggregates of α-synuclein, termed Lewy bodies, is evident in multiple brain regions of patients from PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (Spillantini et al., 1997). There are, to date, no agents with a disease-modifying or neuroprotective indication for PD has been approved (Dehay et al., 2015). Interestingly, it is noteworthy that PD or DLB patients have depressive symptoms (Cummings, 1992; Takahashi et al., 2009; Goodarzi et al., 2016; Schapira et al., 2017), indicating that management of depression in these patients is also important. Therefore, the development of new drugs possessing disease-modifying and/or neuroprotective properties is unmet medical need.

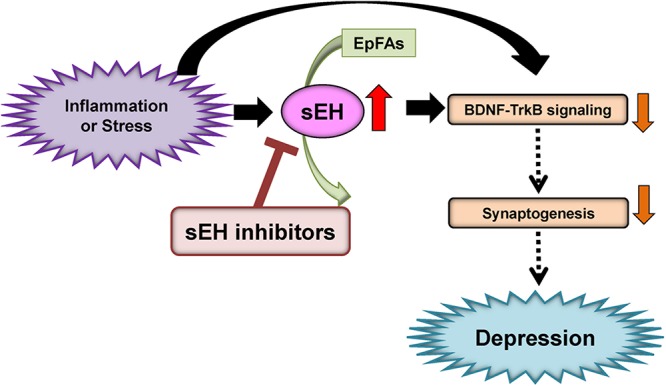

ω-3 PUFAs appear to be neuroprotective for several neurological disorders. It is reported that dietary intake of PUFAs is associated with lower risk of PD (Kamel et al., 2014; Seidl et al., 2014). MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine)-induced neurotoxicity in the striatum and SN has been widely used as an animal model of PD (Sedelis et al., 2001; Jackson-Lewis and Przedborski, 2007). A diet rich in EPA diminished MPTP-induced hypokinesia in mice and ameliorated procedural memory deficit (Luchtman et al., 2012). Recently, we reported that MPTP-induced neurotoxicity [e.g., loss of dopamine transporter (DAT), loss of tyrosine hydrolase (TH)-positive cells, increased endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress] in the striatum and SN was attenuated after subsequent repeated oral administration of TPPU (Ren et al., 2018). MPTP-induced loss of TH-positive cells in the SN is also attenuated by pretreatment with another sEH inhibitor, AUDA [12-(((tricyclo(3.3.1.13,7)dec-1-ylamino)carbonyl)amino)-dodecanoic acid] (Figure 2), although posttreatment with AUDA did not attenuate MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Qin et al., 2015). Furthermore, deletion of the sEH gene protected against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in the mouse striatum (Huang et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2018), while overexpression of sEH in the striatum significantly enhanced MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Ren et al., 2018). Moreover, the expression of the sEH protein in the striatum from MPTP-treated mice was significantly higher than control group. Interestingly, there was a positive correlation between sEH expression and phosphorylation of α-synuclein in the striatum, suggesting that sEH may play a role in the phosphorylation of α-synuclein in the mouse striatum (Ren et al., 2018). Oxylipin analysis showed reduced levels of 8,9-epoxy-5Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatrienoic acid (8,9-EpETrE) prepared from ARA in the striatum of MPTP-treated mice, suggesting increased activity of sEH in this region (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Possible mechanism of role of sEH in the MPTP-induced neurotoxicity. 8,9-EpETrE is prepared from ARA by CYP epoxygenases, and it is metabolized by sEH into 8,9-DiHETrE. Repeated MPTP injections into mice caused increased sEH expression in the striatum, resulting the reduction of anti-inflammatory 8,9-EpETrE in the striatum. Finally, these events cause dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the striatum and SN. Pharmacological inhibition or knock-out of sEH could protect against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in the striatum and SN.

Deposition of α-synuclein has been shown in multiple brain regions of PD and DLB patients (Spillantini et al., 1997). Interestingly, the high levels of DHA in brain areas containing α-synuclein in PD patients may support the possible interaction between α-synuclein and DHA (Fecchio et al., 2018). Protein levels of sEH in the striatum from DLB patients were significantly higher than those of the controls, whereas protein levels of DAT and TH in the striatum from DLB patients were significantly lower than those of controls (Ren et al., 2018). Furthermore, the ratio of phosphorylated α-synuclein to α-synuclein in the striatum from DLB patients was significantly higher than that of controls (Ren et al., 2018). Interestingly, there was a positive correlation between sEH levels and the ratio of phosphorylated α-synuclein to α-synuclein in all subjects (Ren et al., 2018). Collectively, it is likely that increased sEH and resulting increase in phosphorylation of α-synuclein may play a role in the pathogenesis of PD.

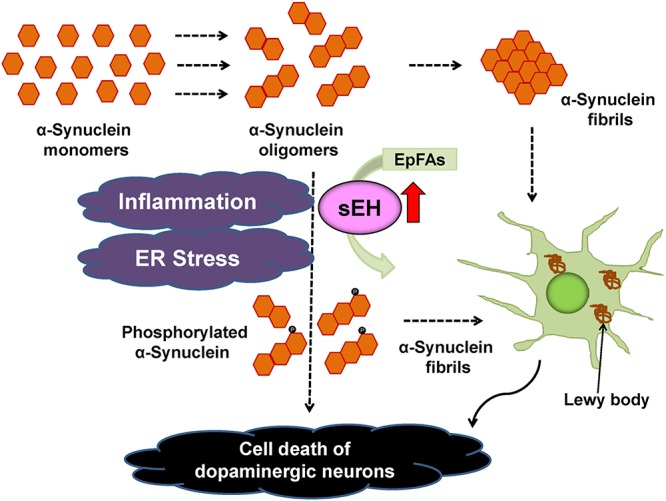

The PARK2 is one of the familial forms of PDs caused by a mutation in the PARKIN gene (Imaizumi et al., 2012). In addition, the expression of EPHX2 mRNA in human PARK2 iPSC-derived neurons was higher than that of healthy control group. Treatment with TPPU protected against apoptosis in human PARK2 iPSC-derived neurons (Ren et al., 2018). These findings suggest that increased activity of sEH in the striatum plays a key role in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders such as PD and DLB although common polymorphisms within EPHX2 do not appear to be important risk factors for PD (Farin et al., 2001). Accumulation of aggregated α-synuclein is the pathological hallmark of PD and DLB although its precise role is not understood. Our data suggest a possible interaction between phosphorylation of α-synuclein and sEH expression in the striatum from DLB patients. Taken all together, it is likely that sEH could represent a promising therapeutic target for α-synuclein-related neurological disorders such as PD and DLB (Borlongan, 2018; Ren et al., 2018; Figure 5). In addition, there are also several approaches (e.g., a small-interfering RNA, immunotherapies, enhancement of autophagy) to reduce α-synuclein production (Stoker et al., 2018).

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism of the role of sEH in the pathogenesis of PD and DLB. Inflammation and ER stress can increase the expression of sEH in the striatum, resulting in enhanced metabolism of anti-inflammatory EpFAs, leading to increased phosphorylation of α-synuclein (Ren et al., 2018). The sEH inhibitors may prevent the progression of aggregation of phosphorylated α-synuclein in the brain.

Conclusion Remarks and Future Perspective

Many patients with depression become chronically ill, with several relapses or later recurrences, following initial short-term improvement or remission. Relapses occur at a rate of over 85 percent within a decade of an index depressive episode (Forte et al., 2015; Sim et al., 2015). Therefore, the prevention of relapse and recurrence is important in the management of depression. Taken together, it seems that sEH inhibitors could be prophylactic drugs to prevent or minimize relapses triggered by inflammation and/or stress in remitted patients with depression (Hashimoto, 2016; Ren et al., 2016). In addition, given the comorbidity of depressive symptoms in PD or DLB patients (Cummings, 1992; Takahashi et al., 2009; Goodarzi et al., 2016; Schapira et al., 2017), it is also likely that sEH inhibitors may serve as prophylactic drugs to prevent the progression of PD or DLB in patients.

Some natural compounds with sEH inhibitory action were reported. MMU [1,3-bis (4-methoxybenzyl)urea](Figure 2), the most abundant (45.3 μg/g dry root weight from the plant Pentadiplandra brazzeana), showed an IC50 of 92 nM via fluorescent assay and a Ki of 54 nM via radioactivity-based assay on human sEH (Kitamura et al., 2015). MMU is about 8-fold more potent than previously reported natural product sEH inhibitor honokiol (Lee et al., 2014; Kitamura et al., 2015; Figure 2). These findings may explain partly the pharmacological mechanisms of the traditional medicinal use of the root of P. brazzeana. Therefore, it is of interest to study whether the use of the root of P. brazzeana has beneficial effects in patients with psychiatric and neurological disorders.

Another topic is the systemic anti-inflammatory effects of sEH inhibition or genetic disruption (Liu et al., 2012; Shahabi et al., 2014). Therefore, it is possible that systemic sEH inhibition may play a role in the beneficial effects in CNS disorders through systemic anti-inflammatory actions of sEH inhibition although further study on the role of systemic anti-inflammation effects of sEH inhibition is needed. It is also suggested that a paracrine role of EET signaling is responsible for a lot of the beneficial effects of EETs (Spector, 2009; Imig, 2016). Therefore, it is possible that up-regulation of sEH, which results in decreased paracrine EET signaling that exasperates the disease state although further study on the role of paracrine role of EETs and sEH is needed.

In conclusion, considering the role of sEH in the metabolism of EpFAs (e.g., EETs, EDPs), treatment of ω-3 PUFAs in combination with a sEH inhibitor could represent a novel therapeutic approach for psychiatric and neurological disorders. This approach may well bridge the currently unmet medical needs for these CNS disorders.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my collaborators who are listed as the co-authors of our papers in the reference list.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was partly supported by grants from AMED, Japan (to KH, JP18dm0107119).

References

- Arnold C., Konkel A., Fischer R., Schunck W. H. (2010). Cytochrome P450-dependent metabolism of omega-6 and omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Pharmacol. Rep. 62 536–547. 10.1016/S1734-1140(10)70311-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascherio P. A., Schwarzschild M. A. (2016). The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 15 1257–1272. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30230-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z. G., Bo A., Wu S. J., Gai Q. Y., Chi I. (2018). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and reduction of depressive symptoms in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 241 241–248. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet R. P., Layé S. (2014). Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15 771–785. 10.1038/nrn3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M. H., Qawasmi A. (2011). Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50 991–1000. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan C. V. (2018). Fatty acid chemical mediator provides insights into the pathology and treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 6322–6324. 10.1073/pnas.1807276115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. P., Su K. P., Mondelli V., Pariante C. M. (2018). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in youths with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials and biological studies. Neuropsychopharmacology 43 534–545. 10.1038/npp.2017.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. T., Bazinet R. P. (2015). β-oxidation and rapid metabolism, but not uptake regulate brain eicosapentaenoic acid levels. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 92 33–40. 10.1016/j.plefa.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. L. (1992). Depression and Parkinson’s disease: a review. Am. J. Psychiatry 149 443–454. 10.1176/ajp.149.4.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., O’Connor J. C., Freund G. G., Johnson R. W., Kelley K. W. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 46–57. 10.1038/nrn2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay B., Bourdenx M., Gorry P., Przedborski S., Vila M., Hunot S., et al. (2015). Targeting α-synuclein for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: mechanistic and therapeutic considerations. Lancet Neurol. 14 855–866. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00006-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis I., Potier B., Heberden C., Vancassel S. (2015). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and brain aging. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 18 139–146. 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati Y., Herrmann N., Swardfager W., Liu H., Sham L., Reim E. K., et al. (2010). A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 67 446–457. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall S. C. (2015). Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: a review of the independent and shared effects of EPA, DPA and DHA. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7:52. 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre H. A., Air T., Pradhan A., Johnston J., Lavretsky H., Stuart M. J., et al. (2016). A meta-analysis of chemokines in major depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 68 1–8. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farin F. M., Janssen P., Quigley S., Abbott D., Hassett C., Smith-Weller T., et al. (2001). Genetic polymorphisms of microsomal and soluble epoxide hydrolase and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacogenetics 11 703–708. 10.1097/00008571-200111000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecchio C., Palazzi L., de Laureto P. P. (2018). α-Synuclein and polyunsaturated fatty acids: molecular basis of the interaction and implication in neurodegeneration. Molecules 23:E1531. 10.3390/molecules23071531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte A., Baldessarini R. J., Tondo L., Vázquez G. H., Pompili M., Girardi P. (2015). Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 178 71–78. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. S., Hammock B. D. (1980). Distribution and properties of a mammalian soluble epoxide hydrase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 29 389–395. 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90518-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden S. A., Covington H. E., Berton O., Russo S. J. (2011). A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat. Protoc. 6 1183–1191. 10.1038/nprot.2011.361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi Z., Mrklas K. J., Roberts D. J., Jette N., Pringsheim T., Holroyd-Leduc J. (2016). Detecting depression in Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 87 426–437. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso G., Micek A., Marventano S., Castellano S., Mistretta A., Pajak A., et al. (2016). Dietary n-3 PUFA, fish consumption and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Affect. Disord. 205 269–281. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumusoglu S. B., Stevens H. E. (2018). Maternal inflammation and neurodevelopmental programming: a review of preclinical outcomes and implications for translational psychiatry. Biol. Psychiatry 85 107–121. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapakoski R., Mathieu J., Ebmeier K. P., Alenius H., Kivimäki M. (2015). Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1β, tumour necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 49 206–215. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan B., Ryan T., Hibbeln J. R., Murray I. T., Glynn S., Ramsden C. E., et al. (2016). Efficacy of omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 209 192–201. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock B. D., Gill S. S., Stamoudis V., Gilbert L. I. (1976). Soluble mammalian epoxide hydratase: action on juvenile hormone and other terpenoid epoxides. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 53 263–265. 10.1016/0305-0491(76)90045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T. R., Hammock B. D. (2013). Soluble epoxide hydrolase: gene structure, expression and deletion. Gene 526 61–74. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2015). Inflammatory biomarkers as differential predictors of antidepressant response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 7796–7801. 10.3390/ijms16047796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2016). Soluble epoxide hydrolase: a new therapeutic target for depression. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 20 1149–1151. 10.1080/14728222.2016.1226284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2018). Essential role of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling in mood disorders: overview and future perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 9:1182. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennebelle M., Otoki Y., Yang J., Hammock B. D., Levitt A. J., Taha A. Y., et al. (2017). Altered soluble epoxide hydrolase-derived oxylipins in patients with seasonal major depression: an exploratory study. Psychiatry Res. 252 94–101. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M. C., Tung C. Y., Chen H. E. (2018). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in prevention and treatment of maternal depression: putative mechanism and recommendation. J. Affect. Disord. 238 47–61. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. J., Wang Y. T., Lin H. C., Lee Y. H., Lin A. M. Y. (2018). Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition attenuates MPTP-induced in the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system: involvement of α-synuclein aggregation and ER stress. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 138–144. 10.1007/s12035-017-0726-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi Y., Okada Y., Akamatsu W., Koike M., Kuzumaki N., Hayakawa H., et al. (2012). Mitochondrial dysfunction associated with increased oxidative stress and α-synuclein accumulation in PARK2 iPSC-derived neurons and postmortem brain tissue. Mol. Brain 5:35. 10.1186/1756-6606-5-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig J. D. (2012). Epoxides and soluble epoxide hydrolase in cardiovascular physiology. Physiol. Rev. 92 101–130. 10.1152/physrev.00021.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig J. D. (2016). Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid on endothelial and vascular function. Adv. Pharmacol. 77 105–141. 10.1016/bs.apha.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig J. D. (2018). Prospective for cytochrome P450 epoxygenase cardiovascular and renal therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 192 1–19. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig J. D., Hammock B. D. (2009). Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8 794–805. 10.1038/nrd2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Lewis V., Przedborski S. (2007). Protocol for the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Proc. 2 141–151. 10.1038/nprot.2006.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson K. L., Endo T., Darwesh A. M., Samokhvalov V., Seubert J. M. (2017). Cytochrome P450-derived eicosanoids and heart function. Pharmacol. Ther. 179 47–83. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jump D. B. (2002). The biochemistry of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 277 8755–8758. 10.1074/jbc.R100062200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia L. V., Lang A. E. (2015). Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 386 896–912. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel F., Goldman S. M., Umbach D. M., Chen H., Richardson G., Barber M. R., et al. (2014). Dietary fat intake, pesticide use, and Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20 82–87. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S., Morisseau C., Inceoglu B., Kamita S. G., De Nicola G. R., Nyegue M., et al. (2015). Potent natural soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors from Pentadiplandra brazzeana baillon: synthesis, quantification, and measurement of biological activities in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 10:e0117438. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C. A., Freitas T. H., Stubbs B., Maes M., Solmi M., Veronese N., et al. (2018). Peripheral alterations in cytokine and chemokine levels after antidepressant drug treatment for major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 4195–4206. 10.1007/s12035-017-0632-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaChance L., McKenzie K., Taylor V. H., Vigod S. N. (2016). Omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acid ratio in patients with ADHD: a meta-analysis. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 25 87–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layé S., Nadjar A., Joffre C., Bazinet R. P. (2018). Anti-inflammatory effects of omega-3 fatty acids in the brain: physiological mechanisms and relevance to pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 70 12–38. 10.1124/pr.117.014092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. H., Ch S. J., Lee S. Y., Lee J. Y., Ma J. Y., Kim Y. H., et al. (2014). Discovery of soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors from natural products. Food Chem. Toxicol. 64 225–230. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. Y., Chang C. H., Chong M. F., Chen H., Su K. P. (2017). Polyunsaturated fatty acids in perinatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 82 560–569. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. Y., Huang S. Y., Su K. P. (2010). A meta-analytic review of polyunsaturated fatty acid compositions in patients with depression. Biol. Psychiatry 68 140–147. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Dang H., Li D., Pang W., Hammock B. D., Zhu Y. (2012). Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates high-fat-diet-induced hepatic steatosis by reduced systemic inflammatory status in mice. PLoS One 7:e39165. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Vicario C., Alcaraz-Quiles J., García-Alonso V., Rius B., Hwang S. H., Titos E., et al. (2015). Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase modulates inflammation and autophagy in obese adipose tissue and liver: role for omega-3 epoxides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 536–541. 10.1073/pnas.1422590112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchtman D. W., Meng Q., Song C. (2012). Ethyl-eicosapentaenoate (E-EPA) attenuates motor impairments and inflammation in the MPTP-probenecid mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 226 386–396. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Ren Q., Yang C., Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., et al. (2017). Antidepressant effects of combination of brexpiprazole and fluoxetine on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. Psychopharmacology 234 525–533. 10.1007/s00213-016-4483-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechawar N., Savitz J. (2016). Neuropathology of mood disorders: do we see the stigmata of inflammation? Transl. Psychiatry 6:e946. 10.1038/tp.2016.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello A. H., Gassenferth A., Souza L. R., Fortunato J. J., Rezin G. T. (2014). ω-3 and major depression: a review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 26 178–185. 10.1017/neu.2013.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Haroon E., Felger J. C. (2017). Therapeutic implications of brain-immune interactions: treatment in translation. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 334–359. 10.1038/npp.2016.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Maletic V., Raison C. L. (2009). Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 65 732–741. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Raison C. L. (2016). The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16 22–34. 10.1038/nri.2015.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocking R. J., Harmsen I., Assies J., Koeter M. W., Ruhé H. G., Schene A. H. (2016). Meta-analysis and meta-regression of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 6:e756. 10.1038/tp.2016.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisseau C., Hammock B. D. (2013). Impact of soluble epoxide hydrolase and epoxyeicosanoids on human health. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 53 37–58. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler E. J., Hyman S. E. (2010). Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13 1161–1169. 10.1038/nn.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. W., Morisseau C., Hammock B. D. (2005). Epoxide hydrolases: their roles and interactions with lipid metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 44 1–51. 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. W., Morisseau C., Harris T. R., Hammock B. D. (2003). The soluble epoxide hydrolase encoded by EPXH2 is a bifunctional enzyme with novel lipid phosphate phosphatase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 1558–1563. 10.1073/pnas.0437724100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota K., Hammock B. D. (1980). Cytosolic and microsomal epoxide hydrolases: differential properties in mammalian liver. Science 207 1479–1481. 10.1126/science.7361100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polokowski A. R., Shakil H., Carmichael C. L., Reigada L. C. (2018). Omega-3 fatty acids and anxiety: a systematic review of the possible mechanisms at play. Nutr. Neurosci. 28 1–11. 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1525092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X., Wu Q., Lin L., Sun A., Liu S., Li X., et al. (2015). Soluble epoxide hydrolase deficiency or inhibition attenuates MPTP-induced Parkinsonism. Mol. Neurobiol. 52 187–195. 10.1007/s12035-014-8833-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison C. L., Lowry C. A., Rook G. A. (2010). Inflammation, sanitation, and consternation: loss of contact with coevolved, tolerogenic microorganisms and the pathophysiology and treatment of major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67 1211–1224. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q., Ma M., Ishima T., Morisseau C., Yang J., Wagner K. M., et al. (2016). Gene deficiency and pharmacological inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase confers resilience to repeated social defeat stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 E1944–E1952. 10.1073/pnas.1601532113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q., Ma M., Yang J., Nonaka R., Yamaguchi A., Ishikawa K. I., et al. (2018). Soluble epoxide hydrolase plays a key role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 E5815–E5823. 10.1073/pnas.1802179115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris J., Murphy J., Mischoulon D., Papakostas G. I., Fava M., Berk M., et al. (2016). Adjunctive nutraceuticals for depression: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am. J. Psychiatry 173 575–587. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15091228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira A. H. V., Chaudhuri K. R., Jenner P. (2017). Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18 435–450. 10.1038/nrn.2017.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Van Zeeland A. A., Bloss C. S., Tewhey R., Bansal V., Torkamani A., Libiger O., et al. (2014). Evidence for the role of EPHX2 gene variants in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 19 724–732. 10.1038/mp.2013.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelis M., Schwarting R. K. W., Huston J. P. (2001). Behavioral phenotyping of the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 125 109–125. 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00309-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl S. E., Santiago J. A., Bilyk H., Potashkin J. A. (2014). The emerging role of nutrition in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:36 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahabi P., Siest G., Visvikis-siest S. (2014). Influence of inflammation on cardiovascular protective effects of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Drug Metab. Rev. 46 33–56. 10.3109/03602532.2013.837916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih P. B. (2017). Integrating multi-omics biomarkers and postprandial metabolism to develop personalized treatment for anorexia nervosa. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 132 69–76. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih P. B., Yang J., Morisseau C., German J. B., Zeeland A. A., Armando A. M., et al. (2016). Dysregulation of soluble epoxide hydrolase and lipidomic profiles in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 21 537–546. 10.1038/mp.2015.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim K., Lau W. K., Sim J., Sum M. Y., Baldessarini R. J. (2015). Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18:pyv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector A. A. (2009). Arachidonic acid cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl.), S52–S56. 10.1194/jlr.R800038-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M. G., Schmidt M. L., Lee V. M. Y., Trojanowsky J. Q., Jakes R., Goedert M. (1997). α-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388 839–840. 10.1038/42166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoker T. B., Torsney K. M., Barker R. A. (2018). Emerging treatment approaches for Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 12:693 10.3389/fnins.2018.00693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sublette M. E., Ellis S. P., Geant A. L., Mann J. J. (2011). Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72 1577–1584. 10.4088/JCP.10m06634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swardfager W., Hennebelle M., Yu D., Hammock B. D., Levitt A. J., Hashimoto K., et al. (2018). Metabolic/inflammatory/vascular comorbidity in psychiatric disorders; soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) as a possible new target. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 87 56–66. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S., Mizukami K., Yasuno F., Asada T. (2009). Depression associated with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and the effect of somatotherapy. Psychogeriatrics 9 56–61. 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2009.00292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart P., Nicolaou A., Woodward D. F. (2015). Endocannabinoids and their oxygenation by cyclo-oxygenases, lipoxygenases and other oxygenases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851 366–376. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K., Vito S., Inceoglu B., Hammock B. D. (2014). The role of long chain fatty acids and their epoxide metabolites in nociceptive signaling. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 11 2–12. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K. M., McReynolds C. B., Schmidt W. K., Hammock B. D. (2017). Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for pain, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 180 62–76. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal C., Konkel A., Schunck W. H. (2015). Cytochrome p450 enzymes in the bioactivation of polyunsaturated Fatty acids and their role in cardiovascular disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 851 151–187. 10.1007/978-3-319-16009-2_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] (2017). Depression. Available at: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Cai H., Song J., Chang Q. (2017). The effects of sEH inhibitor on depression-like behavior and neurogenesis in male mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 95 2483–2492. 10.1002/jnr.24080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Qu Y., Abe M., Nozawa D., Chaki S., Hashimoto K. (2017). (R)-Ketamine shows greater potency and longer lasting antidepressant effects than its metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine. Biol. Psychiatry 82 e43–e44. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Ren Q., Qu Y., Zhang J. C., Ma M., Dong C., et al. (2018). Mechanistic target of rapamycin-independent antidepressant effects of (R)-ketamine in a social defeat stress model. Biol. Psychiatry 83 18–28. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Shirayama Y., Zhang J. C., Ren Q., Yao W., Ma M., et al. (2015). R-ketamine: a rapid-onset and sustained antidepressant without psychotomimetic side effects. Transl. Psychiatry 5:e632. 10.1038/tp.2015.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. J., Bruno D., Pomara N. (2014). A review of the relationship between pro-inflammatory cytokines and major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 169 15–20. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Wu J., Fujita Y., Yao W., Ren Q., Yang C., et al. (2014). Antidepressant effects of TrkB ligands on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18:pyu077. 10.1093/ijnp/pyu077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., et al. (2017a). Blockade of interleukin-6 receptor in the periphery promotes rapid and sustained antidepressant actions: a possible role of gut-microbiota-brain axis. Transl. Psychiatry 7:e1138. 10.1038/tp.2017.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., et al. (2017b). Prophylactic effects of sulforaphane on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 39 134–144. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Hashimoto K. (2016a). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-TrkB signaling in inflammation-related depression and potential therapeutic targets. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14 721–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Ren Q., Yang C., Dong C., Ma M., et al. (2016b). Depression-like phenotype by deletion of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: role of BDNF-TrkB in nucleus accumbens. Sci. Rep. 6:36705. 10.1038/srep36705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]