Abstract

Purpose:

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can promote patient-centered care in multiple ways: (1) using an individual patient’s PRO data to inform his/her management, (2) providing PRO results from comparative research studies in patient educational materials/decision aids, and (3) reporting PRO results from comparative research studies in peer-reviewed publications. Patients and clinicians endorse the value of PRO data; however, variations in how PRO measures are scored and scaled, and in how the data are reported, make interpretation challenging and limit their use in clinical practice. We conducted a modified-Delphi process to develop stakeholderengaged, evidence-based recommendations for PRO data display for the three above applications to promote understanding and use.

Methods:

The Consensus Panel included cancer survivors/caregivers, oncologists, PRO researchers, and application-specific end-users (e.g., electronic health record vendors, decision aid developers, journal editors). We reviewed the data display issues and their evidence base during pre-meeting webinars. We then surveyed participants’ initial perspectives, which informed discussions during an in-person meeting to develop consensus statements. These statements were ratified via a post-meeting survey.

Results:

Issues addressed by consensus statements relevant to both individual- and researchdata applications were directionality (whether higher scores are better/worse) and conveying score meaning (e.g., none/mild/moderate/severe). Issues specific to individual-patient data presentation included representation (bar charts vs. line graphs) and highlighting possibly concerning scores (absolute and change). Issues specific to research-study results presentation included handling normed data, conveying statistically significant differences, illustrating clinically important differences, and displaying proportions improved/stable/worsened.

Conclusions:

The recommendations aim to optimize accurate and meaningful interpretation of PRO data.

Keywords: patient-reported outcomes, consensus statements, cancer, data display, clinical practice

INTRODUCTION

With the increasing emphasis on patient-centered care, patients’ perspectives, collected using standardized patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures of, for example, symptoms, functional status, and well-being, are playing a greater role in clinical care and research [1–8]. There are multiple applications of PRO data, including, among others, (1) using an individual patient’s data to inform his/her care; (2) providing PRO results from comparative research studies (e.g., clinical trials) in patient educational materials and decision aids to inform patients’ understanding of the patient-centered outcomes associated with different treatment options; and (3) reporting PRO results from comparative research studies in peer-reviewed publications to inform clinicians of the treatment impacts, both for their own knowledge and for counseling patients.

Both patients and clinicians endorse the value of PROs in the three applications described above, but they also report challenges interpreting the meaning and implications of PRO data [9–11]. These challenges result in part from the lack of standardization in how PRO measures are scored and scaled, and in how the data are reported. For example, on some PRO questionnaires, higher scores are always better; on other PRO questionnaires, higher scores reflect “more” of the outcome and are therefore better for function domains but worse for symptoms. Some PRO measures are scaled 0–100, with the best and worst outcomes at the extremes, whereas others are normed to, for example, a general population average of 50. There are also variations in how PRO results are reported – in some cases as mean scores over time, in other cases as the proportion of patients meeting a responder definition (improved/stable/worsened). The challenges in interpreting PRO results limit patients’ and clinicians’ use of the data in clinical practice.

In previous research, we investigated different approaches for displaying PRO data for the three applications described above (individual patient data, research data presented to patients, research data presented to clinicians) to identify the graphical formats that were most accurately interpreted and rated the clearest [12–17]. At the conclusion of that research study, that study’s Stakeholder Advisory Board (SAB) advised that the evidence generated was sufficient to inform the development of recommendations for PRO data display for those three applications and suggested that we engage a broader group of stakeholders via a consensus process to develop the recommendations. This paper reports on the results of that project.

METHODS

We conducted a stakeholder-driven, evidence-based, modified-Delphi process to develop recommendations for displaying PRO data in three different applications: individual patient data for monitoring/management, research results presented to patients in educational materials/decision aids, and research results presented to clinicians in peer-reviewed publications. We used a standard modified-Delphi approach, consisting of a pre-meeting survey relevant to the application of interest, a face-to-face meeting, and a post-meeting survey. The first two applications were addressed during an in-person meeting in February 2017, and the third application was addressed during an in-person meeting in October 2017. For simplicity, we refer to these as Meeting #1 and #2. The meetings addressed different applications; issues that were relevant across applications were handled in the context of each application separately.

Because much of the evidence base guiding this process emerged from studies in oncology, we focused specifically on the cancer context. In addition to the project team and this project’s SAB, we purposefully invited representatives from key stakeholder groups: cancer patients/caregivers, oncology clinicians, PRO researchers, and stakeholders specific to particular applications (e.g., electronic health record vendors for individual patient data, decision aid experts for research data presented to patients, journal editors for research data presented to clinicians).

Prior to each in-person meeting, we held a webinar during which we oriented participants to the purpose of the project, the specific data display issues that we were addressing for the relevant applications (Table 1, column 1), and the evidence base regarding the options for those data display issues. The following parameters informed the considerations: (1) recommendations should work on paper (static presentation); (2) presentation in color is possible (but it should be interpretable in grayscale); and (3) additional functionality in electronic presentation is possible (but not part of standards). Notably, during the meeting discussions, additional guiding principles were established: (1) displays should be as simple and intuitively interpretable as possible; (2) it is reasonable to expect that clinicians will need to explain the data to patients; and (3) education and training support should be encouraged to be available.

Table 1:

| Meeting #1 | Meeting #2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue | Application 1: Individual Patient Data | Application 2: Research Results Presented to Patients (i.e. Educational Materials and Decision Aids) | Application 3: Research Results Presented to Clinicians (i.e. PeerReviewed Publications) | Comments | |||||

| Directionality of PRO Scores | There is no easy solution to the issue of directionality. There is a split in the “intuitive” interpretation of symptom scores, with some people expecting that higher scores would be “better” and others expecting that higher scores would be “more” of the symptom (and, therefore, worse). | The Consensus Panel acknowledges the challenges associated with directionality. There is a split in the “intuitive” interpretation of symptom scores, with some people expecting that higher scores would be “better” and others expecting that higher scores would be “more” of the symptom (and, therefore, worse). | |||||||

| The Consensus Panel warned against trying to change current instruments – even if only how the data are displayed (e.g., “flipping the axes” where required for symptom scores so that lines going up are always better). | The Consensus Panel recommends against changing the scoring of current instruments. | Meeting #2 was more comfortable with the notion of changing the directionality in some situations in journal publications. | |||||||

| PRO data presentation should avoid mixing score direction in a single display. | PRO data presentation should avoid mixing score direction in a single display. In cases where this is not possible, authors should consider changing the directionality in the display to be consistent. | ||||||||

| Mixed directionality between domains can cause confusion for both clinicians and patients. There is a need to address this potential confusion by using exceptionally clear labeling, titling, and other annotations. | There is a need for exceptionally clear labeling, titling, and other annotations. | Meeting #2 did not see the need to emphasize confusion. | |||||||

| Conveying Score Meaning | Descriptive labels (e.g., none/mild/moderate/severe) along the y-axis are helpful and should be used when data supporting their location on the scale are available. | ||||||||

| At a minimum, anchors for the extremes should be included (e.g., none/severe), as these labels also help with the interpretation of directionality. Labels for the middle categories (e.g., mild/moderate) should be included if evidence is available to support the relevant score ranges for each label. | Meeting #2 determined that this statement was redundant with the one above. | ||||||||

| In addition to the descriptive y-axis labels, reference values for comparison populations should be included if they are available. | In addition to the descriptive y-axis labels, reference values for comparison populations should be considered for inclusion if they are available. | The change during Meeting #2 was made to be consistent with the recommendation for displaying reference population norms below. | |||||||

| Score Representation | When presenting individual patient PRO scores, there is value in using consistent representation (i.e., line graphs, bar charts, etc.). | Because the display of research results is driven by the analytic strategy, both mean scores over time and proportions were addressed for research data | |||||||

| Line graphs are the preferred approach for presenting individual patient PRO scores over time. | |||||||||

| Conveying Possibly Concerning Results (Absolute Scores) | It is very important to show results that are possibly concerning in absolute terms, assuming the data to support a concerning range of results are available. | ||||||||

| The display of possibly concerning PRO results should be consistent with how possibly concerning results for other clinical data (e.g., lab tests) are displayed in the institution (comparison with other data in the electronic health record was uniquely considered for this issue). | |||||||||

| Conveying Possibly Concerning Results (Change in Score) | Patients tend to value an indication of score worsening that is possibly concerning. | ||||||||

| Normed Scoring | PRO data presentation needs to accommodate instruments the way they were developed, with or without normed scoring. | ||||||||

| One can decide if/when to show the norm visually (with a line on the graph), understanding that displaying it might provide additional interpretive value, but at the cost of greater complexity. | One can decide if/when to show the reference population norm visually (e.g., with a line on the graph), understanding that displaying it might provide additional interpretive value, but potentially at the cost of greater complexity. | ||||||||

| Comparison to the norm might be less relevant in the context where the primary focus is the choice between treatments. | Display of the norm might be less relevant in the context where the primary focus is the choice between treatments. | ||||||||

| If a norm is displayed: • It is necessary to describe the reference population and label the norm as clearly as possible (recommend “average” rather than “norm”) • It also requires deciding what reference population to show (to the extent that options are available). • It will need to be explained to patients that this normed population may not be applicable to a given patient. |

If a norm is displayed: • It is necessary to describe the reference population and label the norm as clearly as possible (recommend “average” rather than “norm”). • It also requires deciding what reference population to show (to the extent that options are available). |

The bolded text was seen as appropriate for patient educational materials/decision aids, but not for journal publications. | |||||||

| Clinically Important Differences | Patients may find information regarding clinically important differences between treatments to be confusing, but it is important for them to know what differences “matter” if they are going to make an informed decision. | Clinically important differences between treatments should be indicated with a symbol of some sort (described in a legend). The use of an asterisk is not recommended (as it is often used to indicate statistical significance). | |||||||

| If there is no defined clinically important difference, that also needs to be in the legend and/or the text of the paper. | |||||||||

| Conveying Statistical Significance | The data suggest that clinicians and others appreciate p-values; however, the Consensus Panel recognizes a move away from reporting them (and toward the use of confidence limits to illustrate statistical significance). Regardless of whether p-values are reported, confidence intervals should always be displayed. | ||||||||

| Proportions Changed | Pie charts are the preferred format for displaying proportion meeting a responder definition (improved, stable, worsened), so long as the proportion is also indicated numerically. | Responder analysis results should be displayed visually. | The data supporting pie charts were stronger for presentation to patients than for presentation to clinicians/researchers | ||||||

| Reasonable options include bar charts, pie charts, or stacked bar charts. | |||||||||

Underlining indicates minor textual differences between statements across the different applications.

Bolding indicates substantive differences between statements across the different applications.

After the pre-meeting webinar, we surveyed participants’ initial perspectives using Qualtrics, a leading enterprise survey company, with protections for sensitive data, used by colleges and universities around the world [18]. Specifically, for each issue, we first asked participants to rate whether there ought to be a standard on that topic. Response options were Important to Present Consistently, Consistency Desirable, Variation Acceptable, and Important to Tailor to Personal Preferences. Regardless of their response to this question, we asked participants to indicate what the standard should be, with alternative approaches for addressing that particular issue as the response options. For example, for data presented to patients, the options for presenting proportions included pie charts, bar charts, and icon arrays, based on the available evidence base [16]. Following each question, participants were asked to indicate the rationale behind their responses in text boxes. A summary of the pre-meeting survey results and comments was circulated prior to the meeting.

At each in-person meeting, we addressed each of the data display issues, briefly summarizing the evidence base and the feedback from the pre-meeting survey before opening up the topic for discussion. At Meeting #1, the participants aimed to be consistent across the two applications, when possible. For Meeting #1 topics also addressed during Meeting #2, after an initial discussion, the consensus statements from Meeting #1 were shared for the Meeting #2 group’s consideration, with the possibility of accepting the statement unchanged, modifying it, discarding it, or developing a new statement.

Following the discussion, participants voted using an audience response system (to ensure anonymity) on whether there should be a standard, and in cases where a standard was supported, what that standard should be. Issues that were not considered appropriate for a standard, and topics for further research, were also noted. After the meeting, the consensus statements were circulated to participants via Qualtrics. Each participant was asked whether each consensus statement was “acceptable” or “not acceptable,” and if the latter, to indicate why in a text box. The funders had no role in the project design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing; or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

There were 28 participants on the Meeting #1 Consensus Panel, and a slightly different set of 27 participants on the Meeting #2 Consensus Panel (See Acknowledgements and Appendix Table 1). The panel included (not mutually exclusive): 15 doctor or nurse clinicians, 10 participants who identified as patient or caregiver advocates, 12 participants with PhDs, and 6 members of journal editorial boards. There were 22 females and 14 males. Of the 28 Meeting #1 participants, 26 completed the pre-meeting survey, 22 attended the in-person meeting, and all 28 completed the post-meeting survey. Of the 27 Meeting #2 participants, 26 completed the premeeting survey, 18 attended the in-person meeting, and 26 completed the post-meeting survey.

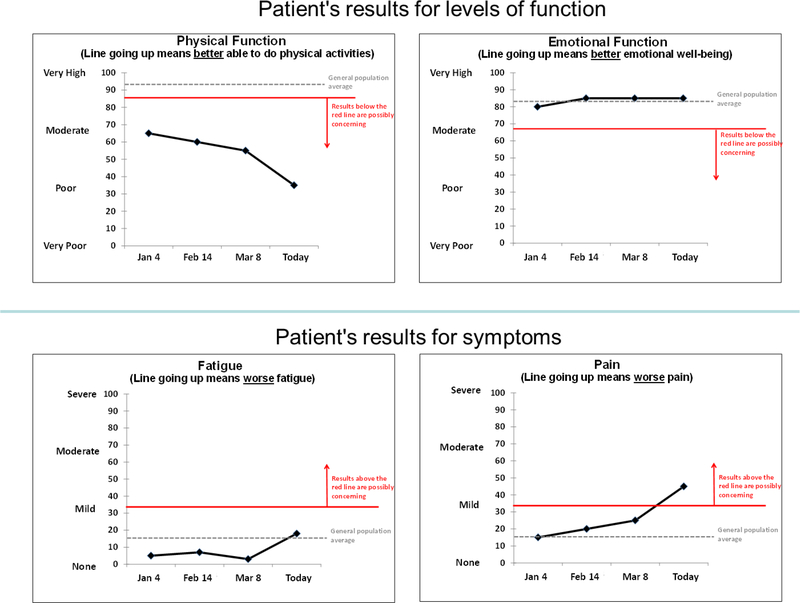

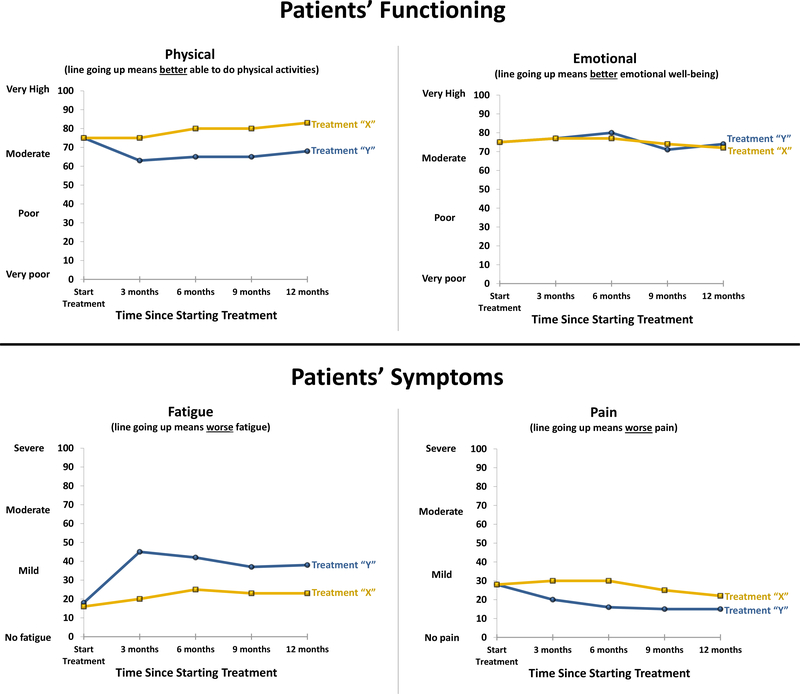

Post-meeting endorsement of the Meeting #1 draft consensus statements ranged from 89%100%, and for Meeting #2 ranged from 88%−100%, across the recommendations. Table 1 displays the consensus statements for each of the three applications, with the final column commenting on differences across applications, where relevant. Table 2 reports the areas identified for further research. Figures 1, 2 and 3 illustrate an implementation of the recommendations for line graphs for each of the three applications, respectively.

Table 2:

Areas Identified for Future Research

| For all applications: |

| • To investigate approaches to address the inherent confusion associated with inconsistency in directionality across instruments. |

| • To explore whether the evidence supporting better interpretation accuracy and clarity associated with the “better” directionality may be informative for future measure development and application. Specifically, to investigate whether, when PROs are used and developed in the future, preference should be given to measures where higher scores always indicate better outcomes. |

| • To identify the specific score ranges associated with the descriptive y-axis labels (particularly those in the middle [e.g., mild, moderate]) for PRO instruments – and the best methods for identifying these score ranges. Specifically, while the extreme categories (e.g., none, severe) can generally be placed at the lowest and highest scores, for many PRO measures, the score ranges that would be considered mild or moderate, for example, may not have been established. Research is needed to identify the point ranges representing the middle categories (e.g., mild or moderate) for different PRO measures – and to identify methods for making these determinations. |

| For individual-level data |

| • To determine if indicating changes greater than the established minimally important difference for the instrument would be clinically valued in practice. |

| • To determine whether the proportionality of time on the x-axis is an important issue, and if it is, how to address it. |

| For research data presented to patients: |

| • To consider how the data indicating challenges with accurately interpreting normed scores may be important for clinical implementation. Specifically, given the evidence demonstrating challenges accurately interpreting normed scores for presentation to patients, further research is needed to investigate how to handle normed scores for this application of PRO data. |

| For research data presented to patients and to clinicians/researchers |

| • To identify effective approaches for indicating clinically important differences. |

Fig. 1.

Graphical Illustration of the Recommendations for Individual Patient Data Line Graphs

Fig. 2.

Graphical Illustration of the Recommendations for Research Data Line Graphs Presented to Patients in Educational Materials/Decision Aids

Fig. 3.

Graphical Illustration of the Recommendations for Research Data Line Graphs Presented to Clinicians in Peer-Reviewed Journal Publications

There were two issues that were addressed for all three applications: directionality of PRO score display and conveying score meaning. Across the three applications, the Consensus Panels agreed that the two different ways people interpret a line going up for symptoms (some expect “up” to always be better, others expect “up” to indicate more of the symptom) creates challenges for interpretation. Both Consensus Panels recommended using exceptionally clear labeling, titling, and other annotations to address this potential confusion, and warned against mixing score direction in a single display (i.e., a single figure). Whereas the Meeting #1 Consensus Panel advised against any change in how PRO scores are displayed to make the direction consistent, the Meeting #2 Consensus Panel could envision rare circumstances in journal publications where changing the directionality of display for consistency would be appropriate (e.g., when only one of many outcomes is scored in the opposite direction). However, the Panel noted that, in those cases, it is important that meta-analyses can identify the original scores in the publication. The Consensus Panels agreed that further research is needed regarding how to address the inherent confusion associated with inconsistency in directionality across instruments.

For conveying score meaning, across the three applications, the Consensus Panels agreed that descriptive labels (e.g., none/mild/moderate/severe) along the y-axis are helpful and should be used when data exist to support their placement on the scale. The Meeting #1 Consensus Panel explicitly stated that placement of the extremes (e.g., none/severe) could be included and acknowledged that evidence regarding placement of the middle categories (e.g., mild/moderate) might not be available. Specifically, the extreme categories (e.g., none, severe) can generally be placed at the lowest and highest scores, but, for many PRO measures, the score ranges that would be considered mild or moderate, for example, may not have been established. That is, it is not always clear at what point on the score continuum a symptom becomes mild or moderate. The Meeting #2 Consensus Panel felt this elaboration regarding the lack of evidence supporting placement of the middle categories was implied by the first statement. Both Consensus Panels noted the need for further research regarding the best methods for identifying the score ranges associated with the descriptive labels. The Meeting #1 Consensus Panel recommended including reference values for comparison populations, when available, for presenting either individuallevel data or research data to patients. The Meeting #2 Consensus Panel took a softer approach, recommending only that inclusion of the reference values be considered.

For issues specific to individual patient data (Application 1), the Consensus Panel recommended showing line graphs of scores over time and including some indication of possibly concerning results in absolute terms (where evidence exists to support the concerning PRO score range). The Consensus Panel noted the need for more research regarding how to display possibly concerning changes. There was some discussion of whether the slope of the line would be sufficient to convey important worsening. An issue was also raised during the discussions regarding whether it is important that the time points displayed on the x-axis be proportional to the time elapsed; this topic was recommended for further research.

For presentation of research results, both to patients and to clinicians (Applications 2 and 3), the Consensus Panels addressed normed scoring, conveying clinically important differences, and displaying the proportion meeting a responder definition (i.e. improved/stable/worsened). Both Consensus Panels agreed that PRO data display should accommodate both normed and nonnormed scoring. While there were some minor differences in the consensus statement wording, they also agreed that display of the norm is optional, depending on the trade-offs between added interpretive value vs. potentially greater complexity. They also noted that information about the norm may be less relevant in the context where the focus is on the comparison between treatment options. Across both applications, if a norm is shown, which norm to show must be decided (to the extent options are available), and it is important to describe the reference population and label the norm clearly. For presentation to patients, it is also necessary to explain that the reference population may not be applicable to a given patient. Given the evidence presented to the Meeting #1 Consensus Panel, which demonstrated challenges accurately interpreting normed scores for presentation to patients [16], the Meeting #1 Consensus Panel also recommended further research investigating how to handle normed scores for this application of PRO data.

The Meeting #1 Consensus Panel agreed that it is important to present to patients information regarding clinically important differences between treatments, but felt that further research was needed to determine the best approaches for doing so. The Meeting #2 Consensus Panel recommended indicating clinically important differences in journal publications using some sort of symbol (described in a legend), but not an asterisk due to its association with statistical significance. They also advised reporting in the legend and/or in the text of the paper when the clinically meaningful difference for a PRO measure is unknown.

For proportions meeting a responder definition, for presentation to patients (Application 2), the Meeting #1 Consensus Panel recommended using pie charts and indicating the proportion numerically. For presentation to clinicians in journal publications, the Meeting #2 Consensus Panel agreed that the results should be presented visually but did not recommend a single format for doing so, noting that bar charts, pie charts, and stacked bar charts are reasonable approaches. The difference between the recommendations for the two applications resulted from differences in the evidence base [16–17]. Specifically, the data strongly supported pie charts over the other options for presenting data to patients, but there was no clear advantage between pie charts and bar charts for presenting data to clinicians.

The issue of conveying statistical significance was uniquely addressed for presentation of research data to clinicians (Application 3). The Consensus Panel recognized the conflict between evidence demonstrating that clinicians and others appreciate p-values vs. the move away from reporting p-values to reporting confidence intervals. They concluded that, regardless of whether p-values are reported, confidence intervals should always be displayed. For example, on line graphs confidence limits can be used for individual timepoints, with p-values for the overall difference between treatments over time.

DISCUSSION

PRO data have enormous potential to promote patient-centered care, but for this potential to be realized, it is critical that clinicians and patients understand what the scores mean. Guided by the evidence-base from the literature, we conducted a modified-Delphi consensus process to develop recommendations for PRO data display to promote understanding and use in practice.

Strengths of the process include the engagement of a broad range of key stakeholders. To ensure all panelists could provide their input anonymously, we conducted pre-meeting and post-meeting surveys, and used an audience response system at the in-person meetings. The modified Delphi methodology facilitated the development of the consensus recommendations. One limitation of this process is that it focused on the cancer context specifically, given that much of the evidencebase resulted from oncology studies. Further research is needed to investigate whether there are any differences in the underlying evidence in different patient populations, including those with lower literacy, that would necessitate modifications to these recommendations for PROs. Notably, other clinical data from trials also need careful presentation and clear messaging to enable communication and interpretation, but this project focused specifically on PROs.

We limited the process to display recommendations that would work on paper and could be interpreted in grayscale. The additional functionalities that are becoming increasingly feasible with electronic data display were not considered, and would be appropriate for future recommendation development. To the extent possible, the Consensus Panels aimed to provide consistent recommendations across the three applications. When recommendations differed by application, this was generally driven by variation in needs of the target audience in that specific context. While these recommendations apply to current domain-scored PRO measures, as novel PRO instruments are developed, alternative approaches to data display may be required.

This consensus process produced clear guidance for graphically displaying PRO data and identified areas requiring further research. Next steps include working with stakeholders and developing tools (e.g., templates) to facilitate the implementation of these recommendations in practice – and evaluating their impact. The long-term goal is to promote patient-centered care by optimizing accurate and meaningful interpretation of PRO results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Drs. Snyder and Smith are members of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins (P30CA006973). The Consensus Panel Participants included the project Stakeholder Advisory Board (SAB) and other invitees, in addition to the project team named authors. The SAB members were Daniel Weber (National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship); Ethan Basch, MD (Lineberger Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina); Neil Aaronson, PhD (Netherlands Cancer Institute); Bryce Reeve, PhD (Duke University); Galina Velikova, BMBS(MD), PhD (University of Leeds, Leeds Institute of Cancer and Pathology); Andrea Heckert, PhD, MPH (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute); Eden Stotsky-Himelfarb (patient representative); Cynthia Chauhan† (patient representative); Vanessa Hoffman, MPH (caregiver representative); Patricia Ganz, MD* (UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center); Lisa Barbera, MD, MPA†(University of Toronto and Cancer Care Ontario). Additional Consensus Panel participants included Elizabeth Frank* (patient advocate); Mary Lou Smith, JD† (patient advocate); Arturo Durazo (patient advocate); Judy Needham (patient advocate); Shelley Fuld Nasso (National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship); Robert Miller, MD (American Society of Clinical Oncology); Tenbroeck Smith, MA (American Cancer Society); Deborah Struth, MSN, RN, PhD(c) (Oncology Nursing Society); Alison Rein, MS (AcademyHealth); Andre Dias, PhD* (International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement); Charlotte Roberts, MBBS, BSc† (International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement); Nancy Smider, PhD* (Epic); Gena Cook* (Navigating Cancer); Jakob Bjorner, MD, PhD* (Optum); Holly Witteman, PhD* (Laval University); James G. Dolan, MD* (University of Rochester); Jane Blazeby, MD, MSc† (University of Bristol); Robert M. Golub, MD† (JAMA); Christine Laine, MD, MPH† (Annals of Internal Medicine); Scott Ramsey, MD, PhD† (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center). Additional details on all meeting participants are listed in Appendix Table 1. (*Meeting 1 only; †Meeting 2 only)

Funding: This study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Drs. Snyder and Smith are members of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins (P30CA006973).

Appendix

Appendix Table 1:

Meeting Participants

| Name | Background & Expertise (at the time of participation) |

|---|---|

| PROJECT TEAM | |

| Claire Snyder, PhD | • Principal Investigator • Expertise in use of PROs in clinical practice |

| Michael Brundage, MD, MSc | • Co-Principal Investigator • Practicing radiation oncologist • Expertise in use of PROs in clinical practice and clinical trials |

| Elissa Bantug, MHS* | • Patient Co-Investigator • Breast cancer survivor and advocate • Expertise in health communication |

| Katherine Smith, PhD | • Co-Investigator • Expertise in health communication |

| Bernhard Holzner, PhD | • Led previous work on PRO data presentation in Europe • Expertise in PROs in clinical practice • Associate Editor, Quality of Life Research |

| STAKEHOLDER ADVISORY BOARD | |

| Daniel Weber | • Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma survivor • Director of Communications at the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship |

| Ethan Basch, MD | • Practicing medical oncologist • Developer of patient-reported toxicity measure • Member of PCORI Methodology Committee |

| Neil Aaronson, PhD | • Expertise in using PROs in clinical practice • Principal Investigator for the development of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality-of-life questionnaire • Associate Editor, Journal of the National Cancer Institute |

| Bryce Reeve, PhD | • Psychometrician • Instrumental in the design of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) |

| Galina Velikova, BMBS(MD), PhD | • International Society for Quality of Life Research official representative • Expertise in using PROs in oncology clinical practice and clinical trials • Practicing medical oncologist |

| Andrea Heckert, PhD, MPH | • PCORI-nominated staff member |

| Eden StotskyHimelfarb | • Colorectal cancer survivor • Nurse working with colorectal cancer survivors |

| Cynthia Chauhan† | • Breast and renal cell cancer survivor with multiple comorbidities • Active research patient advocate • Prior and current clinical trial participant |

| Vanessa Hoffman, MPH | • Personal caregiving experience to her mother • Previous work with the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network |

| Patricia Ganz, MD* | • Practicing medical oncologist • Developer of the Cancer and Rehabilitation Evaluation System • PRO researcher through national clinical trials network • Editor-in-Chief, Journal of the National Cancer Institute |

| Lisa Barbera, MD, MPA† | • Practicing radiation oncologist • Provincial lead of the patient-reported outcomes program at Cancer Care Ontario |

| INVITED PARTICIPANTS | |

| Elizabeth Frank* | • Breast cancer survivor and PCORI Patient Ambassador • Patient advocate for national committees (e.g., NCI Breast Cancer Steering Committee, Patient Advocate Steering Committee) |

| Mary Lou Smith, JD† | • Breast cancer survivor • Patient advocate for national clinical trials network committees |

| Arturo Durazo | • American Cancer Society patient advocate; Blood cancer/NH lymphoma cancer survivor • Patient advocate for local/state policy, clinical trials, and advisory committees • PhD candidate focusing on health communications |

| Judy Needham | • Breast cancer survivor, retired Communications and Marketing Director • Chair, Patient Advocate Committee, Canadian Cancer Trials Group (CCTG); and member of various other CCTG committees • British Columbia Cancer Agency, Member, Clinical Trials Strategic Advisory Committee |

| Shelley Fuld Nasso | • Chief Executive Officer, National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship • Patient advocate • Member, NCI National Council of Research Advisors |

| Robert Miller, MD | • American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Vice President and Medical Director, CancerLinQ® |

| Tenbroeck Smith, MA |

• American Cancer Society, Strategic Director, Patient-Reported Outcomes • PRO researcher |

| Deborah Struth, MSN, RN, PhD(c) | • Oncology Nursing Society, Research Associate • Work focused in quality measurement and improvement • PhD candidate studying cognitive human factors and nursing care outcomes |

| Alison Rein, MS | • Senior Director, Evidence Generation and Translation - AcademyHealth |

| Andre Dias, PhD* | • Benchmarking Lead, International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) • Vice President Strategy & New Program Development |

| Charlotte Roberts, MBBS, BSc† | • Vice President of Standardization, International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement |

| Nancy Smider, PhD* | • Epic electronic health record’s Director of Research Informatics • Leader of Epic’s annual Research Advisory Council conference • Background in biopsychosocial models of health/disease with a focus on patient selfreports |

| Gena Cook* | • Chief Executive Officer of Navigating Cancer, a patient relationship management technology solution for cancer programs for patient engagement, care management, and population health that operates with any EHR system • Chair, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Foundation Board • Director, Washington Technology Industry Association Benefit Trust |

| Jakob Bjorner, MD, PhD* | • Psychometrician • Chief Science Officer at Optum |

| Holly Witteman, PhD* | • Expertise in decision aids, visualization, and human factors |

| James G. Dolan, MD* | • General internist • Medical decision-making researcher • Clinical decision support researcher and Society of Medical Decision-Making Special Interest Group Lead |

| Jane Blazeby, MD, MSc† | • Leader of initiatives to standardize the use of PROs in clinical trials • Practicing surgeon |

| Robert M. Golub, MD† | • Deputy Editor, JAMA • General internist • Educator in medical decision making and evidence-based medicine |

| Christine Laine, MD, MPH† | • Editor in Chief, Annals of Internal Medicine • Practicing general internist |

| Scott Ramsey, MD, PhD† | • Associate Editor, Journal of Clinical Oncology • Practicing general internist |

Meeting 1 only;

Meeting 2 only

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors declare a conflict of interest.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Guidance for Industry. Patient Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Federal Register, 74(35), 65132–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acquadro C, Berzon R, Dubois D, Leidy NK, Marquis P, Revicki D, et al. (2003). Incorporating the patient’s perspective into drug development and communication: an ad hoc task force report of the Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Harmonization Group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration, February 16, 2001. Value Health, 6, 522–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhalgh J (2009). The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res, 18, 115–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK (2009). Use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Lancet, 374, 369–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen RE, Snyder CF, Abernethy AP, Basch E, Reeve BB, Roberts A, et al. (2014). A review of electronic patient reported outcomes systems used in cancer clinical care. J Oncol Pract, 10, e215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Till JE, Osoba D, Pater JL, Young JR (1994). Research on health-related quality of life: dissemination into practical applications. Qual Life Res, 3(4), 279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Au H-J, Ringash J, Brundage M, Palmer M, Richardson H, Meyer RM, et al. (2010). Added value of health-related quality of life measurement in cancer clinical trials: the experience of the NCIC CTG. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res, 10(2), 119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder C (eds). (2005). Outcomes Assessment in Cancer: Measures, Methods, and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brundage M, Bass B, Ringash J, Foley K (2011). A knowledge translation challenge: clinical use of quality of life data from cancer clinical trials. Qual Life Res, 20, 979–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezjak A, Ng P, Skeel R, Depetrillo AD, Comis R, Taylor KM (2001). Oncologists’ use of quality of life information: results of a survey of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group physicians. Qual Life Res, 10, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Wolff AC, Carducci MA, Herman JM, Wu AW, et al. (2013). Feasibility and value of PatientViewpoint: a web system for patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Psychooncology, 22, 895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brundage MD, Smith KC, Little EA, Bantug ET, Snyder CF, PRO Data Presentation Stakeholder Advisory Board. (2015). Communicating patient-reported outcome scores using graphic formats: Results from a mixed methods evaluation. Qual Life Res, 24, 2457–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bantug ET, Coles T, Smith KC, Snyder CF, Rouette J, Brundage MD, et al. (2016). Graphical displays of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) for use in clinical practice: What makes a PRO picture worth a thousand words? Patient Educ Couns, 99, 483–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KC, Brundage MD, Tolbert E, Little EA, Bantug ET, Snyder C, et al. (2016). Engaging stakeholders to improve presentation of patient-reported outcomes data in clinical practice. Support Care Cancer, 24, 4149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder CF, Smith KC, Bantug ET, Tolbert EE, Blackford AL, Brundage MD, et al. (2017). What do these scores mean? Presenting patient-reported outcomes data to patients and clinicians to improve interpretability. CANCER, 123, 1848–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolbert E, Snyder C, Bantug E, Blackford A, Smith K, Brundage M, et al. (2016). Graphing group-level data from research studies for presentation to patients in educational materials and decision aids. Qual Life Res, 15, 17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brundage MD, Blackford A, Tolbert E, Smith K, Bantug E, Snyder C, et al. (2018). Presenting comparative study PRO results to clinicians and researchers: Beyond the eye of the beholder. Qual Life Res, 27, 75–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qualtrics Survey Software. Available at: https://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/programs_resources/programs-resources/informatics/qualtricssurvey/. Last accessed: August 7, 2018.