Abstract

Background:

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, specifically the fish oil derived eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), have been proposed as inflammation resolving agents via their effects on adipose tissue.

Objective:

We proposed to determine the effects of EPA and DHA on human adipocyte differentiation and inflammatory activation in vitro.

Methods:

Primary human subcutaneous adipocytes from lean and obese subjects were treated with 100μM EPA and/or DHA throughout differentiation (differentiation studies) or for 72 hours post-differentiation (inflammatory studies). THP-1 monocytes were added to adipocyte wells for co-culture experiments. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose explants from obese subjects were treated for 72 hours with EPA and DHA. Oil-Red-O staining was performed on live cells. Cells were collected for mRNA analysis by qPCR and media collected for protein quantification by ELISA.

Results:

Incubation with EPA and/or DHA attenuated inflammatory response to LPS and monocyte co-culture with reduction in post-LPS mRNA expression and protein levels of IL6, CCL2, and CX3CL1. Expression of inflammatory genes was also reduced in the endogenous inflammatory response in obese adipose. Both DHA and EPA reduced lipid droplet formation and lipogenic gene expression without alteration in expression of adipogenic genes or adiponectin secretion.

Conclusions:

EPA and DHA attenuate inflammatory activation of in vitro human adipocytes and reduce lipogenesis.

Keywords: obesity, adipose, lipid, inflammation, omega-3 fatty acid

1.1. Introduction

In recent years there has been a surge of interest in the effects of long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC n-3 PUFA) on cardiometabolic health. In addition to well established beneficial effects on lipid composition[1, 2], LC n-3 PUFA from fish and fish oil supplements, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and the anti-inflammatory metabolites they produce exert pleiotropic effects to resolve inflammation in human and animal models [3–10]. Notably, these effects are also seen in the low-grade inflammatory state of obesity [11–13] and may be associated with improvement in metabolic parameters[11].

Adipose inflammation and dysfunction is an important link between obesity and its related metabolic dysregulation[14–25]. In animal models, there is evidence that LC n-3 PUFA supplementation favorably modulates adipokine secretion (increased adiponectin and decreased leptin) and reduces adipose tissue inflammation and macrophage infiltration[26–33]. These changes are associated with improvement in insulin signaling and prevention of high fat diet (HFD)-induced adiposity[34]. In the few reported human studies, reduction in adipose tissue inflammation and macrophage infiltration is also suggested[35–37].

Studies in murine cell culture models similarly demonstrate inflammation reducing and resolving effects of LC n-3 PUFA on adipocytes and adipocyte-leukocyte interactions[38]. In the murine 3T3-L1 adipocyte cell line, CD8+ T cells from mice fed fish oils had decreased inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production as well as decreased macrophage chemotaxis[39]. In addition, LC n-3 PUFA have also been shown in 3T3-L1 adipocytes to alter storage of fat in lipid droplets, a key feature of adipogenesis[39–41]. One study performed in primary human adipocytes and adipose noted amelioration of LPS-induced inflammation with concomitant treatment with EPA and DHA[42]. Adiponectin secretion was also induced by treatment with EPA and DHA in primary human adipocytes; effects were additive to those of PPARγ agonist and only partially attenuated by PPAR γ antagonist[43].

The effect of LC n-3 PUFA on human adipocyte differentiation, lipid droplet formation, and adipocyte-leukocyte interaction has not been fully characterized. We hypothesized that EPA and DHA would promote differentiation, reduce lipid droplet formation, and reduce adipocyte-leukocyte inflammatory signaling in primary human adipocytes.

1.2. Materials and Methods

1.2.1. Cell culture

Subcutaneous (gluteal) adipose biopsies were taken from 10 lean, healthy volunteers. Volunteers were aged 18–30 (mean age=22 years) with 60% female and 40% male. Adipose was minced and digested immediately with Type I collagenase (Sigma Aldrich, St Luis, MO) for one hour, centrifuged and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was isolated. Pre-adipocytes from the SVF were cultured and differentiated to adipocytes as previously described[44]. Briefly, cells were grown to confluence in PM4 medium[45] with 10% serum, then differentiated in medium with IBMX, dexamethasone and PPARgamma agonist for 7 days to achieve >80% lipidation.

THP-1 human monocyte line [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA] were grown in RPMI 1640 (Cambrex Bio Science, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), 2mM L-glutamine (corning/Cell-gro), 10mM HEPES (Gibco), 1mN Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco), 1.25 g/L D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100uL/L betamercaptoethanol (Gibco).

For adipose tissue explant experiments, subcutaneous and visceral (abdominal) biopsies were taken from obese subjects undergoing bariatric surgery through the University of Pennsylvania Diabetes Research Core Human Adipose Resource (http://www.med.upenn.edu/idom/adipose.html). Explants were cultured in PM4 media as above.

All human samples were taken as part of clinical studies with approval of the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) Institutional Review Board (IRB) after written informed consent was obtained from all research participants.

1.2.2. Conjugation of LC N-3 PUFA

EPA and DHA (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were reconstituted in DMSO and heated to dissolve. EPA and DHA were then freshly conjugated to BSA by incubating 2 mM of each FA with 0.5 mM of BSA (4:1 molar ratio) at 37 °C before experiments. EPA and DHA were then mixed into cell culture media and applied directly onto cells for the time course specified, after which media was removed and cells were lysed or fresh media applied for LPS stimulation experiments.

1.2.3. Treatments

Oil Red O (Abcam; Cambridge, MA) was applied to fully differentiated adipocytes per manufacturer’s protocol. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was reconstituted in water, mixed in media for a final concentration of 100 ng/mL and applied directly to cells for 4 hours.

1.2.4. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and Quantitative PCR:

Whole adipose tissue was homogenized, or, for in vitro experiments adipocytes were washed and lysed for RNA isolation using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA (500ng) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (ABI; Foster City, CA). Expression of genes was determined by quantitative Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystem 7900 Real-Time PCR system; ABI, Foster City, CA) using TaqMan Universal PCR MasterMix and primers and probes from Applied Biosystems (ABI; Foster City,CA). To control for between-sample differences, mRNA levels were normalized to Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) for each sample by subtracting the Ct for GAPDH from the Ct for the gene of interest, producing a ΔCt value. The ΔCt for each post-treatment sample was compared with the mean ΔCt for all pre-treatment samples in a single individual or experiment using the relative quantitation 2-ΔΔCt method to determine fold change from baseline[46].

1.2.5. Protein extraction and ELISA:

Whole adipose tissue was placed in RIPA buffer, homogenized and protein concentration quantified using Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Then samples were diluted with additional RIPA buffer to equal concentrations (1.5 μg/μl). Primary adipocytes were lysed for protein extraction with RIPA buffer x 30 minutes at 4°C; cell media was collected immediately and frozen. Human adiponectin ELISA (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN) was performed in duplicate according to manufacturer instructions.

1.2.6. Statistics

Continuous variables were compared using student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U depending on whether normality could be assumed. Fisher’s exact test was used for proportions. Unless otherwise specified, data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). To assess differences among time points and between groups our analysis of adiponectin protein levels in adipose and cells used repeated measures ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction for multiple post-hoc comparisons. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

1.3. Results

1.3.1. EPA and DHA attenuate inflammatory mediators in primary human adipocytes

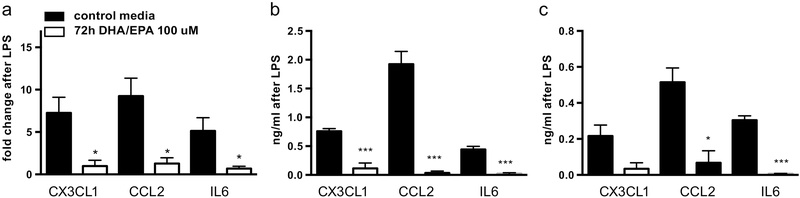

72 hour pre-treatment of mature human adipocytes with 100 μM EPA and DHA attenuated LPS-stimulated induction of inflammatory gene mRNA expression as measured by qPCR (Figure 1a): LPS increased fold change of CX3CL1 in untreated cells to 7.26 +/− 3.19 vs. 0.97 +/− 1.18 in treated cells (p=0.033). Similar patterns were seen for CCL2 [9.23 +/− 3.67 vs.1.28 +/− 1.17 (p=0.023)] and IL6 [5.14 +/−2.69 vs. 0.69 +/− 0.45 (p=0.048)]. Results represent three independent experiments.

Figure 1: EPA and DHA attenuate inflammatory induction in primary human adipocytes.

Pre-treatment of mature human adipocytes with 72 hours of EPA and DHA (100 uM) prior to 4-hour induction with LPS reduced mRNA induction as demonstrated by qPCR(a) and intracellular (b) and secreted protein (c) levels by ELISA of the inflammatory markers CX3CL1, CCL2, and IL6. Figure shows mean and SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, ***P<0.005.

Protein quantification of CX3CL1, CCL2 and IL6 in both cell lysate and media by ELISA assay is also consistent with decreased LPS-induced protein secretion. In the lysate, LPS increased CX3CL1 by 0.75 +/− 0.08 ng/ml in untreated cells, vs. 0.11+/− 0.16 ng/ml in treated cells (p=0.004). Induction of both CCL2 [1.92 +/− 0.39 ng/ml vs. 0.035 +/− 0.056 ng/ml (p=0.001)] and IL6 0.44 +/− 0.09 ng/ml vs. 0.02 +/− 0.025 ng/ml (p=0.002) was similarly decreased in the cell lysate. In the media, we also noted reduction in LPS-stimulated induction of CX3CL1 [0.22 +/ 0.1 ng/ml vs. 0.03 +/− 0.06 ng/ml (p=0.06)], CCL2 [0.52 +/− 0.14 ng/ml vs. 0.07 +/− 0.12 ng/ml (p=0.01)] and IL6 [0.3 +/− 0.04 ng/ml vs. 0.007 +/− 0.002 ng/ml (p=0.0003)] (Figures 1b and c). Effects of individual EPA or DHA treatments were similar but less robust.

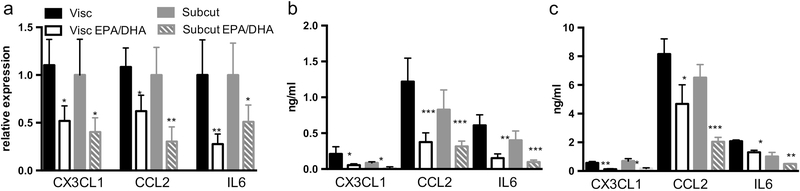

1.3.2. EPA and DHA reduce inflammatory mediators in obese human adipose

Similar anti-inflammatory effects were seen in whole adipose from obese subjects. Fresh adipose explants from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal depots showed reduced mRNA expression and protein quantification in the tissue and explant media for CX3CL1, CCL2 and IL6 after 72 hours of treatment with EPA and DHA at 100 μM (Figure 2 a, b, and c).

Figure 2: EPA and DHA reduce inflammation in human subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue ex vivo.

Treatment of subcutaneous and visceral adipose explants from obese human subjects for 72 hours with EPA and DHA (100 uM) attenuated the intrinsic inflammatory state of tissue as demonstrated by (a) reduced mRNA expression via qPCR and reduction in protein levels by ELISA in adipose tissue (b) and secreted media (c) of the inflammatory markers CX3CL1, CCL2 and IL6. Figure shows mean and SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

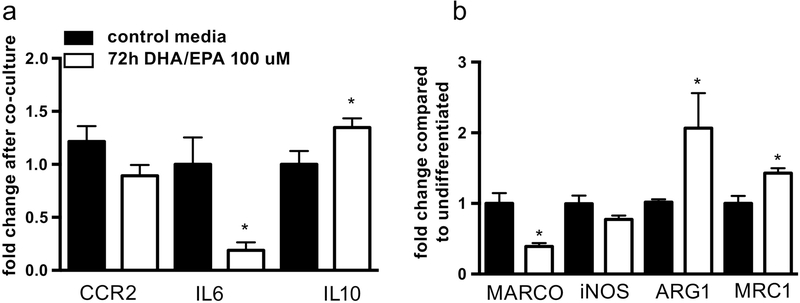

1.3.3. EPA and DHA reduce THP-1 monocyte inflammation induced by adipocyte co-culture and promote M2 macrophage differentiation

Pre-treatment of mature adipocytes with EPA and DHA for 72 hours prior to co-culture with monocytes reduced expression of IL6 and CCL2, with an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il10, in THP-1 monocytes (Figure 3a). Treatment with EPA and DHA during monocyte to macrophage differentiation also increased expression of mRNAs associated with M2 macrophage subtypes (ARG1 and MRC1), while reducing M1-associated genes (MARCO and NOS2) (Figure 3b).

Figure 3: EPA and DHA reduce THP-1 monocyte inflammation induced by adipocyte-monocyte co-culture and promote M2 macrophage differentiation.

(a) Pre-treatment of mature adipocytes with EPA and DHA for 72 hours before co-culture with THP1 monocytes reduced expression of IL6 and CCL2 and induced expression of IL10 in monocytes (b) treatment of monocytes during macrophage differentiation led to increased mRNA expression of the M2 genes ARG1 and MRC1 while reducing expression of M1-associated MARCO and iNOS. Figure shows mean and SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05.

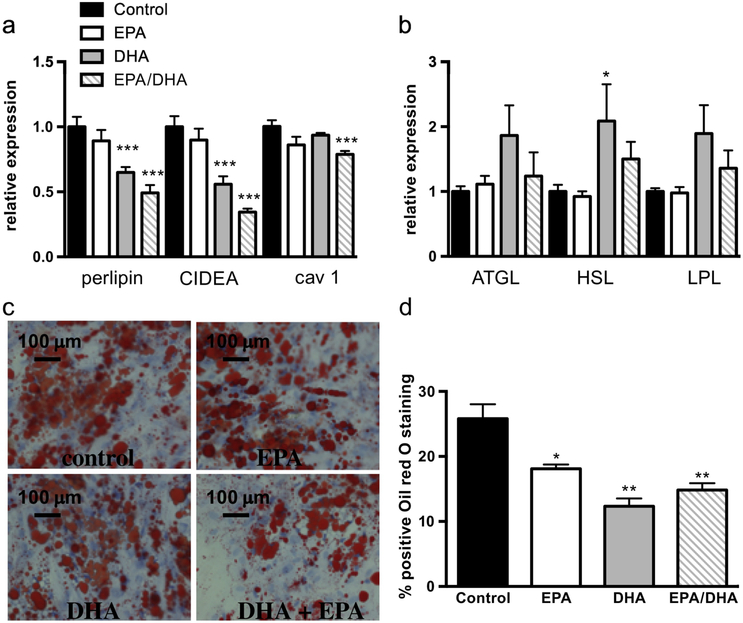

1.3.4. EPA and DHA alter differentiation of primary human adipocytes

When pre-adipocytes were treated with DHA and/or EPA during differentiation, there was alteration in lipogenic and lipolytic gene expression. While both agents led to reduced expression of the lipogenic genes perilipin A, CIDEA, and caveolin 1, DHA had a more profound effect than EPA and the effects were additive (Figure 4a). DHA, but not EPA, caused a trend in decreased expression of the lipolytic genes ATGL, HSL, and LPL (Figure 4b). There was also decrease in size and number of Oil Red O-staining lipid droplets (Figure 4c and d) with both agents. In contrast, there was no change in expression of the adipogenic genes adiponectin and PPARγ with either EPA or DHA (not shown) suggesting a specific effect on lipid droplet formation.

Figure 4: DHA, more than EPA, alters lipid droplet formation in human adipocytes.

as determined by (a) increased mRNA expression of the lipid droplet genes perilipin, CIDEA, and caveolin 1, (b) no significant change of lipolytic genes ATGL, HSL, and LPL and (c) reduced lipid droplet size as visualized with Oil Red O staining (c) and by quantification (d). Figure shows mean and SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

1.4. Discussion

Our studies in primary human adipocytes and ex vivo adipose indicate a clear anti-inflammatory effect of both EPA and DHA, and suggest that this effect can be seen on the more physiologic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity. Further, there is a shift in differentiation of adipocytes towards lipolysis vs. lipogenesis and reduced lipid droplet formation with more significant effects noted with DHA compared to EPA. These studies, the first done in human cell and tissue models, support prior work done in animal in vivo and in vitro models documenting inflammation reducing effects of LC N-3 PUFA as well as changes in lipid droplet formation. Though data on the clinical use of LC N-3 PUFA in human metabolic disease, such as atherosclerosis and diabetes are conflicting[47–52], the pre-clinical evidence suggests there may be beneficial effects in the chronic inflammatory state of obesity.

The changes seen in adipocyte lipid droplet formation is of relevance as lipid droplets are a principal site of energy storage, and their balance is critical to metabolic homeostasis. Both the inability to form sufficient lipid droplets (lipodystrophy) and excessive formation in states of nutrient-excess have been associated with metabolic disease including diabetes to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[53]. This delicate balance between lipid storage and release may underlie the often contradictory data surrounding association of lipid storage genes expression with metabolic health. On one hand, human studies have shown that increased expression of lipogenic genes CIDE and perilipin in adipose were correlated with lower BMI and higher insulin sensitivity, and humans with perilipin deficiency have severe insulin resistance[54]. On the contrary, both CIDEC and perilipin1 knockout mice were protected against obesity and insulin resistance [55], underscoring the importance of human models in understanding lipid physiology.

Effects of LC n-3 PUFA in adipocytes has primarily been shown in mouse models, and overall suggests that both EPA and DHA are involved in varying ways with lipogenesis and lipolysis. In one study of mouse primary adipocytes, EPA treatment led to enlarged lipid droplets and increased expression of the triglyceride synthesis genes GPAT1 and GPAT3 with downregulation of HSL and ATGL expression, suggesting increased fatty acid storage[56]. Pinel et al. found that in vivo supplementation with EPA (but not DHA) reduced leptin and adipose cell hypertrophy compared to HF-fed mice and in vitro EPA induced adiponectin while DHA stimulated leptin expression[57]. Another study, using 3T3L1 adipocytes, showed that EPA reduced lipid droplet size and lipid accumulation, while increasing expression of LPL and HSL and reducing inflammatory effect of LPS[58]. However, two other manuscripts depicting 3T3L1 experiments demonstrated that DHA effects were much stronger than those of EPA. One stated that DHA increased lipolysis and ATGL expression while reducing mRNA expression of lipid droplet promoting perilipin, caveolin-1 and Cidea.[40], while another showed that DHA increased differentiation markers and reduced inflammatory pathways and monocyte migration[59].

Strengths of this study include the use of human cells and tissues, as well as inclusion of obese human samples for physiologic relevance. The limitations primarily involve the utilization of in vitro models, which may not truly reflect in vivo effects of DHA and EPA on human adipose inflammation. The dose chosen was based on in vitro response and my not reflect actual tissue levels obtained by in vivo supplementation. Further, the mechanisms by which DHA and EPA exert inflammation reduction and anti-lipogenic effects remains unclear. Future studies addressing mechanism and clinical trials of human obesity assessing whether treatment with LC N-3 PUFA effects leads to similar effects, and whether these effects are associated with beneficial metabolic outcomes, are needed.

Highlights.

LC n-3 PUFA (EPA&DHA) reduce LPS-induced inflammation in primary human adipocytes

Low-grade obesity-related adipose inflammation was also reduced by EPA and DHA

In co-culture, EPA and DHA promoted M2 vs. M1 macrophage differentiation

LC n-3 PUFA reduced formation of lipid droplets in primary human adipocytes

DHA>EPA induced lipolytic and downregulated lipogenic gene expression

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (DK095913)

We thank the University of Pennsylvania Diabetes Research Center (DRC) for the use of the Human Adipose Resource (P30-DK19525)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Puglisi MJ, Hasty AH, Saraswathi V: The role of adipose tissue in mediating the beneficial effects of dietary fish oil. J Nutr Biochem 2011, 22:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohammadi E, Rafraf M, Farzadi L, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Sabour S: Effects of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on serum adiponectin levels and some metabolic risk factors in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 21:511–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayser P, Mrowietz U, Arenberger P, Bartak P, Buchvald J, Christophers E, Jablonska S, Salmhofer W, Schill WB, Kramer HJ, et al. : Omega-3 fatty acid-based lipid infusion in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998, 38:539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geusens P, Wouters C, Nijs J, Jiang Y, Dequeker J: Long-term effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in active rheumatoid arthritis. A 12-month, double-blind, controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 1994, 37:824–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broughton KS, Johnson CS, Pace BK, Liebman M, Kleppinger KM: Reduced asthma symptoms with n-3 fatty acid ingestion are related to 5-series leukotriene production. Am J Clin Nutr 1997, 65:1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belluzzi A, Brignola C, Campieri M, Pera A, Boschi S, Miglioli M: Effect of an enteric-coated fish-oil preparation on relapses in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 1996, 334:1557–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calder PC: Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Nutrition or pharmacology? Br J Clin Pharmacol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiurchiu V, Leuti A, Dalli J, Jacobsson A, Battistini L, Maccarrone M, Serhan CN: Proresolving lipid mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and maresin 1 are critical in modulating T cell responses. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8:353ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosaraju R, Guesdon W, Crouch MJ, Teague HL, Sullivan EM, Karlsson EA, Schultz-Cherry S, Gowdy K, Bridges LC, Reese LR, et al. : B Cell Activity Is Impaired in Human and Mouse Obesity and Is Responsive to an Essential Fatty Acid upon Murine Influenza Infection. J Immunol 2017, 198:4738–4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laguna-Fernandez A, Checa A, Carracedo M, Artiach G, Petri MH, Baumgartner R, Forteza MJ, Jiang X, Andonova T, Walker ME, et al. : ERV1/ChemR23 Signaling Protects from Atherosclerosis by Modifying oxLDL Uptake and Phagocytosis in Macrophages. Circulation 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baril-Gravel L, Labonte ME, Couture P, Vohl MC, Charest A, Guay V, Jenkins DA, Connelly PW, West S, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. : Docosahexaenoic acid-enriched canola oil increases adiponectin concentrations: a randomized crossover controlled intervention trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015, 25:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sijben JW, Calder PC: Differential immunomodulation with long-chain n-3 PUFA in health and chronic disease. Proc Nutr Soc 2007, 66:237–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dangardt F, Osika W, Chen Y, Nilsson U, Gan LM, Gronowitz E, Strandvik B, Friberg P: Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation improves vascular function and reduces inflammation in obese adolescents. Atherosclerosis 2010, 212:580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR: Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest 2007, 117:175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujisaka S, Usui I, Bukhari A, Ikutani M, Oya T, Kanatani Y, Tsuneyama K, Nagai Y, Takatsu K, Urakaze M, et al. : Regulatory mechanisms for adipose tissue M1 and M2 macrophages in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 2009, 58:2574–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Tordjman J, Poitou C, Darakhshan F, Hugol D, Basdevant A, Aissat A, Guerre-Millo M, Clement K: Human adipose tissue macrophages: m1 and m2 cell surface markers in subcutaneous and omental depots and after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94:4619–4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisberg SP, Hunter D, Huber R, Lemieux J, Slaymaker S, Vaddi K, Charo I, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW, Jr., : CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. J Clin Invest 2006, 116:115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patsouris D, Li PP, Thapar D, Chapman J, Olefsky JM, Neels JG: Ablation of CD11c-positive cells normalizes insulin sensitivity in obese insulin resistant animals. Cell Metab 2008, 8:301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumeng CN, DelProposto JB, Westcott DJ, Saltiel AR: Phenotypic switching of adipose tissue macrophages with obesity is generated by spatiotemporal differences in macrophage subtypes. Diabetes 2008, 57:3239–3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffaut C, Zakaroff-Girard A, Bourlier V, Decaunes P, Maumus M, Chiotasso P, Sengenes C, Lafontan M, Galitzky J, Bouloumie A: Interplay between human adipocytes and T lymphocytes in obesity: CCL20 as an adipochemokine and T lymphocytes as lipogenic modulators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009, 29:1608–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westcott DJ, Delproposto JB, Geletka LM, Wang T, Singer K, Saltiel AR, Lumeng CN: MGL1 promotes adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance by regulating 7/4hi monocytes in obesity. J Exp Med 2009, 206:3143–3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A, Lee J, Goldfine AB, Benoist C, Shoelson S, Mathis D: Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med 2009, 15:930–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lumeng CN, Maillard I, Saltiel AR: T-ing up inflammation in fat. Nat Med 2009, 15:846–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Eto K, Yamashita H, Ohsugi M, Otsu M, Hara K, Ueki K, Sugiura S, et al. : CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med 2009, 15:914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winer S, Chan Y, Paltser G, Truong D, Tsui H, Bahrami J, Dorfman R, Wang Y, Zielenski J, Mastronardi F, et al. : Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat Med 2009, 15:921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baranowski M, Enns J, Blewett H, Yakandawala U, Zahradka P, Taylor CG: Dietary flaxseed oil reduces adipocyte size, adipose monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 levels and T-cell infiltration in obese, insulin-resistant rats. Cytokine, 59:382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hensler M, Bardova K, Jilkova ZM, Wahli W, Meztger D, Chambon P, Kopecky J, Flachs P: The inhibition of fat cell proliferation by n-3 fatty acids in dietary obese mice. Lipids Health Dis, 10:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Titos E, Rius B, Gonzalez-Periz A, Lopez-Vicario C, Moran-Salvador E, Martinez-Clemente M, Arroyo V, Claria J: Resolvin D1 and its precursor docosahexaenoic acid promote resolution of adipose tissue inflammation by eliciting macrophage polarization toward an M2-like phenotype. J Immunol, 187:5408–5418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White PJ, Arita M, Taguchi R, Kang JX, Marette A: Transgenic restoration of long-chain n-3 fatty acids in insulin target tissues improves resolution capacity and alleviates obesity-linked inflammation and insulin resistance in high-fat-fed mice. Diabetes 2010, 59:3066–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeMieux MJ, Kalupahana NS, Scoggin S, Moustaid-Moussa N: Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces adipocyte hypertrophy and inflammation in diet-induced obese mice in an adiposity-independent manner. J Nutr 2015, 145:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todoric J, Loffler M, Huber J, Bilban M, Reimers M, Kadl A, Zeyda M, Waldhausl W, Stulnig TM: Adipose tissue inflammation induced by high-fat diet in obese diabetic mice is prevented by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Diabetologia 2006, 49:2109–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh da Y, Walenta E, Akiyama TE, Lagakos WS, Lackey D, Pessentheiner AR, Sasik R, Hah N, Chi TJ, Cox JM, et al. : A Gpr120-selective agonist improves insulin resistance and chronic inflammation in obese mice. Nat Med 2014, 20:942–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundaram S, Bukowski MR, Lie WR, Picklo MJ, Yan L: High-Fat Diets Containing Different Amounts of n3 and n6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Modulate Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Mice. Lipids 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjursell M, Xu X, Admyre T, Bottcher G, Lundin S, Nilsson R, Stone VM, Morgan NG, Lam YY, Storlien LH, et al. : The beneficial effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on diet induced obesity and impaired glucose control do not require Gpr120. PLoS One 2014, 9:e114942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itariu BK, Zeyda M, Hochbrugger EE, Neuhofer A, Prager G, Schindler K, Bohdjalian A, Mascher D, Vangala S, Schranz M, et al. : Long-chain n-3 PUFAs reduce adipose tissue and systemic inflammation in severely obese nondiabetic patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 96:1137–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spencer M, Finlin BS, Unal R, Zhu B, Morris AJ, Shipp LR, Lee J, Walton RG, Adu A, Erfani R, et al. : Omega-3 fatty acids reduce adipose tissue macrophages in human subjects with insulin resistance. Diabetes 2013, 62:1709–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferguson JF, Xue C, Hu Y, Li M, Reilly MP: Adipose tissue RNASeq reveals novel gene-nutrient interactions following n-3 PUFA supplementation and evoked inflammation in humans. J Nutr Biochem 2016, 30:126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Todorcevic M, Hodson L: The Effect of Marine Derived n-3 Fatty Acids on Adipose Tissue Metabolism and Function. J Clin Med 2015, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monk JM, Liddle DM, De Boer AA, Brown MJ, Power KA, Ma DW, Robinson LE: Fish-oil-derived n-3 PUFAs reduce inflammatory and chemotactic adipokine-mediated cross-talk between co-cultured murine splenic CD8+ T cells and adipocytes. J Nutr 2015, 145:829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barber E, Sinclair AJ, Cameron-Smith D: Comparative actions of omega-3 fatty acids on in-vitro lipid droplet formation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2013, 89:359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wojcik C, Lohe K, Kuang C, Xiao Y, Jouni Z, Poels E: Modulation of adipocyte differentiation by omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids involves the ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Cell Mol Med 2014, 18:590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murumalla RK, Gunasekaran MK, Padhan JK, Bencharif K, Gence L, Festy F, Cesari M, Roche R, Hoareau L: Fatty acids do not pay the toll: effect of SFA and PUFA on human adipose tissue and mature adipocytes inflammation. Lipids Health Dis 2012, 11:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tishinsky JM, Ma DW, Robinson LE: Eicosapentaenoic acid and rosiglitazone increase adiponectin in an additive and PPARgamma-dependent manner in human adipocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19:262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah R, Lu Y, Hinkle CC, McGillicuddy FC, Kim R, Hannenhalli S, Cappola TP, Heffron S, Wang X, Mehta NN, et al. : Gene profiling of human adipose tissue during evoked inflammation in vivo. Diabetes 2009, 58:2211–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skurk T, Ecklebe S, Hauner H: A novel technique to propagate primary human preadipocytes without loss of differentiation capacity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007, 15:2925–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ: Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 2008, 3:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burke MF, Burke FM, Soffer DE: Review of Cardiometabolic Effects of Prescription Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2017, 19:60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sagawa N, Olson NC, Ahuja V, Vishnu A, Doyle MF, Psaty BM, Jenny NS, Siscovick DS, Lemaitre RN, Steffen LM, et al. : Long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are not associated with circulating T-helper type 1 cells: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2017, 125:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poreba M, Mostowik M, Siniarski A, Golebiowska-Wiatrak R, Malinowski KP, Haberka M, Konduracka E, Nessler J, Undas A, Gajos G: Treatment with high-dose n-3 PUFAs has no effect on platelet function, coagulation, metabolic status or inflammation in patients with atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017, 16:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Handelsman Y, Shapiro MD: Triglycerides, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Outcome Studies: Focus on Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Endocr Pract 2017, 23:100–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rylander C, Sandanger TM, Engeset D, Lund E: Consumption of lean fish reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective population based cohort study of Norwegian women. PLoS One 2014, 9:e89845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muley A, Muley P, Shah M: ALA, fatty fish or marine n-3 fatty acids for preventing DM?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev 2014, 10:158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krahmer N, Farese RV Jr., Walther TC: Balancing the fat: lipid droplets and human disease. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5:973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kozusko K, Patel S, Savage DB: Human congenital perilipin deficiency and insulin resistance. Endocr Dev 2013, 24:150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McManaman JL, Bales ES, Orlicky DJ, Jackman M, MacLean PS, Cain S, Crunk AE, Mansur A, Graham CE, Bowman TA, Greenberg AS: Perilipin-2-null mice are protected against diet-induced obesity, adipose inflammation, and fatty liver disease. J Lipid Res 2013, 54:1346–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao M, Chen X: Eicosapentaenoic acid promotes thermogenic and fatty acid storage capacity in mouse subcutaneous adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 450:1446–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinel A, Pitois E, Rigaudiere JP, Jouve C, De Saint-Vincent S, Laillet B, Montaurier C, Huertas A, Morio B, Capel F: EPA prevents fat mass expansion and metabolic disturbances in mice fed with a Western diet. J Lipid Res 2016, 57:1382–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manickam E, Sinclair AJ, Cameron-Smith D: Suppressive actions of eicosapentaenoic acid on lipid droplet formation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Lipids Health Dis 2010, 9:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murali G, Desouza CV, Clevenger ME, Ramalingam R, Saraswathi V: Differential effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid in promoting the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2014, 90:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]