Abstract

Rationale: Chronic lower respiratory diseases (CLRDs), including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, are the fourth leading cause of death. Prior studies suggest that albuminuria, a biomarker of endothelial injury, is increased in patients with COPD.

Objectives: To test whether albuminuria was associated with lung function decline and incident CLRDs.

Methods: Six U.S. population–based cohorts were harmonized and pooled. Participants with prevalent clinical lung disease were excluded. Albuminuria (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio) was measured in spot samples. Lung function was assessed by spirometry. Incident CLRD-related hospitalizations and deaths were classified via adjudication and/or administrative criteria. Mixed and proportional hazards models were used to test individual-level associations adjusted for age, height, weight, sex, race/ethnicity, education, birth year, cohort, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, renal function, hypertension, diabetes, and medications.

Measurements and Main Results: Among 10,961 participants with preserved lung function, mean age at albuminuria measurement was 60 years, 51% were never-smokers, median albuminuria was 5.6 mg/g, and mean FEV1 decline was 31.5 ml/yr. For each SD increase in log-transformed albuminuria, there was 2.81% greater FEV1 decline (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86–4.76%; P = 0.0047), 11.02% greater FEV1/FVC decline (95% CI, 4.43–17.62%; P = 0.0011), and 15% increased hazard of incident spirometry-defined moderate-to-severe COPD (95% CI, 2–31%, P = 0.0021). Each SD log-transformed albuminuria increased hazards of incident COPD-related hospitalization/mortality by 26% (95% CI, 18–34%, P < 0.0001) among 14,213 participants followed for events. Asthma events were not significantly associated. Associations persisted in participants without current smoking, diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions: Albuminuria was associated with greater lung function decline, incident spirometry-defined COPD, and incident COPD-related events in a U.S. population–based sample.

Keywords: epidemiology, spirometry, asthma

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Cross-sectional studies suggest albuminuria is increased in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), among whom it is adversely associated with lung function, gas exchange, and hypoxia. Co-occurrence of pulmonary and renal endothelial cell injury was recently demonstrated on pathological samples in patients with COPD and cigarette smoke–exposed mice, among whom extent of angiopathy was correlated cross-sectionally with albuminuria. Nonetheless, no large-scale, prospective study has tested whether albuminuria is associated with COPD development.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study demonstrates associations between greater albuminuria and accelerated decline in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio, increased incident spirometry-defined COPD, and increased rates of incident clinical chronic lower respiratory disease events, especially COPD events. These associations were independent of smoking, diabetes, hypertension, renal function, and cardiovascular disease. This work supports a role for pulmonary endothelial dysfunction in COPD pathogenesis, suggesting that microvascular mechanisms may be promising targets to treat and prevent COPD.

Chronic lower respiratory diseases (CLRDs) are the fourth leading cause of death and a major source of health care costs (1–4). The CDC defines CLRDs to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma—conditions that share smoking as a cause or contributor, airflow limitation as a physiologic correlate, and acute exacerbations as the major clinical manifestation. No medical therapies have been proven to prevent CLRDs or CLRD-related mortality, which has been rising (5). Identifying biomarkers to predict individuals who are at high CLRD risk would be useful to target prevention strategies (6).

Pulmonary microvascular dysfunction has been directly linked to CLRD pathogenesis. Failure of pulmonary endothelial cell survival causes lung alveolar septal cell apoptosis and emphysema in rats (7, 8). Ceramides, which are mediators of endothelial function, have been implicated in the development of airflow obstruction, airway inflammation, and lung hyperinflation in mouse models and humans (9–11). Imaging-based microvascular biomarkers such as retinal vein caliber, myocardial blood flow, and pulmonary microvascular blood flow have been correlated with adult lung function and COPD severity (12–14), although conflicting results have been obtained (15, 16). No large-scale, prospective study has tested whether a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction is associated with CLRD development.

Albuminuria is a commonly used biomarker of endothelial damage in the kidneys (17–19) and correlates with microvascular dysfunction throughout the body (20, 21), including the pulmonary circulation (22). Prior literature has shown correlations between albuminuria and COPD: greater albuminuria was observed in patients with COPD, and, in cross-sectional analyses, albuminuria has been adversely associated with COPD severity, lung function, gas exchange, and hypoxia (12, 22–28). Nonetheless, the biological and clinical significance of this work has remained uncertain due to relatively small samples, often using case-control designs; the possibility of reverse causation; and potential confounding effects of aging, smoking, and comorbid disease. We therefore tested whether albuminuria was associated with development of CLRD in a large, multiethnic, population-based sample of U.S. adults.

Some results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of abstracts (29, 30).

Methods

NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study

The NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study (31) harmonized and pooled data from large U.S. epidemiologic cohorts that conducted lung function assessments during the last four decades. The current report is limited to six cohorts with albuminuria measurements and repeated spirometry and/or ascertainment of CLRD events: ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities); CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults); CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study); FHS-O (Framingham Offspring Cohort); Health ABC (Health, Aging, and Body Composition); and MESA (Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) (32–39). The timing of recruitment, albuminuria measurement and spirometry, and events follow-up are shown in Figure E1 in the online supplement.

Participants with an albumin-to-creatinine ratio >2,200 mg/g were excluded from all primary analyses (19), as were those with prevalent clinical CLRD, which was defined at time of albuminuria measurement by self-reported prior physician diagnoses of asthma, chronic bronchitis, emphysema and/or COPD, or inhaler use, assessed by medication inventory (31, 40).

Only five cohorts (CARDIA, CHS, FHS-O, Health ABC, and MESA) that performed spirometry examinations both coincident and subsequent to albuminuria measurement were included in lung function analyses. Spirometry examinations occurring prior to albuminuria measurement were not analyzed. Participants with prevalent airflow limitation, defined as FEV1/FVC < lower limit of normal (LLN) (41), were excluded. Furthermore, since the disease of interest is characterized by an obstructive spirometric pattern, we excluded participants demonstrating a potentially confounding restrictive pattern, defined as FEV1/FVC ≥ LLN and FVC < LLN (42). Of note, spirometric exclusion criteria were not applied in primary events analyses since baseline spirometry was only available in a subset of the participants with events follow-up.

All studies were approved by Institutional Review Boards at participating institutions and all participants provided written informed consent.

Albuminuria

Urine collection was performed via standardized protocols and processed in central laboratories (Table E1). Technologies differed across studies, yet measures were performed similarly: urine albumin measured by nephelometry or immunoturbidometry (42), and urine creatinine assessed by the Jaffe method (43). These were used to calculate the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, hereafter called “albuminuria.”

Spirometry

Prebronchodilator lung function was measured using water-seal, dry-rolling-seal, or flow-sensing spirometers following American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines current at the time of assessment (44–47). To harmonize spirometry data, we applied a standardized quality grading system based upon 2005 ATS/European Respiratory Society guidelines for acceptability and reproducibility (31, 44).

Incident moderate-to-severe COPD was defined as FEV1/FVC < LLN and FEV1 < 80% at the final spirometry examination (48).

CLRD Events

Four cohorts (ARIC, CHS, Health ABC, and MESA) prospectively attempted to contact participants every 6–12 months for events surveillance and to collect medical records for all hospitalizations and deaths, and hence provided CLRD events data (Table E2).

Clinical events committees adjudicated CLRD-related clinical events in Health ABC (hospitalizations/deaths) and CHS (deaths only). For hospitalizations and deaths in ARIC and MESA, and nonfatal hospitalizations in CHS, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes were used to classify events attributable to asthma (ICD-9 493, ICD-10 J45–46), COPD (ICD-9 496, ICD-10 J44), chronic bronchitis (ICD-9 490–491, ICD-10 J40–42), and emphysema (ICD-9 492, ICD-10 J43), following a previously validated protocol (49).

A CLRD-related event was defined as first hospitalization or death adjudicated as primarily or secondarily attributable to CLRD, or, when adjudication was lacking, those with CLRD listed in any diagnosis field. In prior work in MESA and a second cohort, 82% of such administratively defined events were physician confirmed as evidence of clinical CLRD (50).

A secondary endpoint, severe CLRD event, was defined as first hospitalization or death adjudicated as primarily attributable to CLRD or, when adjudication was lacking, with CLRD coded as the primary discharge diagnosis or underlying cause of death. This administrative definition was previously found to have a positive predictive value of 97% for physician-adjudicated CLRD exacerbations (50).

CLRD events were stratified into events attributed to asthma versus COPD, the latter of which was defined to include COPD, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema.

Covariates

Covariates were harmonized systematically prior to pooling (31). Smoking status, pack-years of smoking, race/ethnicity, sex, and educational attainment were self-reported. Height, weight, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured using standard methods. Blood glucose and cholesterol were measured on fasting samples. Medication use was assessed by self-report or validated inventories. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation using creatinine (51). Diabetes was defined by self-report, fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl, or relevant medications. Hypertension was defined by blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or relevant medications.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of participants at the time of albuminuria measurement were tabulated and compared by albuminuria categories defined to balance statistical and clinical considerations. Symmetric distributional thresholds were set at 2 mg/dl (10th percentile), 3 mg/dl (25th percentile), 6 mg/dl (50th percentile), 12 mg/dl (75th percentile), and 30 mg/dl (90th percentile), which is the upper limit for the normal clinical range (19).

Separate models were performed using albuminuria categories and natural log–transformed albuminuria as categorical and continuous predictors, respectively, and model fit was compared via the Akaike information criterion.

Linear mixed models predicting lung function from baseline albuminuria, time since albuminuria assessment (years), and their multiplicative interaction term were used to test associations between albuminuria and lung function. The coefficient for albuminuria was interpreted as the cross-sectional association with initial lung function. The coefficient for (albuminuria) × (time since albuminuria measurement) was interpreted as the longitudinal association with rate of change in lung function. Longitudinal associations were reported as absolute rate of change per year and also as relative rate of change, defined as (absolute rate of change)/(average model-based rate of change per year in the full sample); negative values indicate associations with greater rate of decline. Effect estimates were reported per albuminuria category and per SD of ln albuminuria.

Cohort-specific unstructured covariance matrices were used to model variability between and within participants, allowing for differences between cohorts. This statistical approach was chosen over random effects modeling (with heterogeneous residual variances across both examinations and study cohorts) because the former allows for autocorrelation in repeated measures and nonlinear effects of time. Post hoc confirmatory analyses demonstrated that our approach achieved a better model fit than did random effects models (results not shown).

Associations between albuminuria and incident spirometry-defined COPD and CLRD events were tested via proportional hazards regression. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by residual plots. The time to event was treated as age at event, with left truncation at age at albuminuria measurement. Non-CLRD mortality was censored. The study was treated as a stratum term, allowing for cohort-specific differences in the underlying survival function. In secondary analyses, the competing risks of COPD events, asthma events, and non-CLRD mortality were analyzed in competing risks regression, and the time to event variable was the time since albuminuria measurement.

Models were sequentially adjusted for a priori confounders, including baseline age (centered), birth-year (centered), height, weight, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, cohort, eGFR, total cholesterol, hypertension, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diabetes, and relevant medications. In spirometry models, height, weight, and smoking status were time varying; for time-invariant terms, both cross-sectional and longitudinal associations were estimated.

Effect modification was examined in stratified models and by three-way multiplicative interaction terms. Sensitivity analyses were conducted in participants with prevalent CLRD and in “low-risk” participants without diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2, or current smoking. For comparison with the pooled analysis and evaluation of between-cohort heterogeneity, fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses were performed. Extended events models were additionally adjusted for baseline FEV1/FVC.

Analyses were completed in SAS v9.4.

Role of Funding Sources

NHLBI staff routinely monitored the performance of component studies but neither the NHLBI nor the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were involved in analysis, interpretation, or writing of this report, nor the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

There were 31,877 participants with albuminuria measures, lung function, and/or events (Figure E2).

Among 11,911 participants included in lung function analyses, mean age at albuminuria measurement was 60 years, 55% were female, 64% were non-Hispanic white, 26% were African American, 6% were Hispanic/Latino American, and 4% were Asian American (Tables 1 and E3). Fifty-one percent were never-smokers and 11% were current smokers. Among ever-smokers, median pack-years of smoking history was 4. Diabetes and hypertension were present in 11% and 45%, respectively. Median albuminuria was 5.6 mg/g, and mean eGFR was 83 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Included in Analyses of Longitudinal Lung Function, by Category of Albuminuria (NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study)

| Albuminuria Categories |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 mg/dl | 2–3 mg/dl | 3–6 mg/dl | 6–12 mg/dl | 12–30 mg/dl | ≥30 mg/dl | |

| Total sample, no. | 988 | 1,311 | 3,945 | 2,706 | 1,823 | 1,138 |

| No. spirometry exams, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.0) | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.0) |

| Years of spirometry follow-up, mean (SD) | 8.2 (5.7) | 6.5 (5.0) | 5.7 (5.0) | 5.4 (5.0) | 5.5 (5.2) | 4.2 (4.8) |

| Cohort, no. (%) | ||||||

| CARDIA | 258 (26.1) | 528 (40.3) | 1.185 (30.0) | 458 (16.9) | 200 (11.0) | 103 (9.1) |

| CHS | 41 (4.2) | 114 (8.7) | 537 (13.6) | 497 (18.4) | 357 (19.6) | 254 (22.3) |

| FHS Offspring | 436 (44.1) | 223 (17.0) | 599 (15.2) | 507 (18.7) | 446 (24.5) | 217 (19.1) |

| Health ABC | 118 (11.9) | 133 (10.1) | 405 (10.3) | 466 (17.2) | 358 (19.6) | 289 (25.4) |

| MESA | 135 (13.7) | 313 (23.9) | 1,219 (30.9) | 778 (28.8) | 462 (25.3) | 275 (24.2) |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 54.6 (14.8) | 53.0 (17.0) | 56.9 (16.9) | 62.9 (15.6) | 65.9 (14.5) | 68.4 (13.9) |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 416 (42.1) | 560 (42.7) | 2,116 (53.6) | 1,657 (61.2) | 1,151 (63.1) | 563 (49.5) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.7 (4.7) | 27.4 (5.1) | 27.5 (5.3) | 27.5 (5.4) | 27.5 (5.3) | 28.0 (5.4) |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||||

| European American | 740 (74.9) | 787 (60.0) | 2,426 (61.5) | 1,751 (64.7) | 1,179 (64.7) | 686 (60.3) |

| African American | 213 (21.6) | 427 (32.6) | 1,078 (27.3) | 639 (23.6) | 447 (24.5) | 324 (28.5) |

| Asian American | 12 (1.2) | 37 (2.8) | 180 (4.6) | 145 (5.4) | 93 (5.1) | 51 (4.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 23 (2.3) | 60 (4.6) | 261 (6.6) | 171 (6.3) | 104 (5.7) | 77 (6.8) |

| Education status, no. (%) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 52 (5.3) | 79 (6.0) | 306 (7.8) | 251 (9.3) | 157 (8.6) | 119 (10.5) |

| High school | 262 (26.5) | 303 (23.1) | 965 (24.5) | 674 (24.9) | 492 (27.0) | 299 (26.3) |

| Some college | 243 (24.6) | 353 (26.9) | 1,010 (25.6) | 630 (23.3) | 419 (23.0) | 263 (23.1) |

| College or more | 364 (36.8) | 545 (41.6) | 1,561 (39.6) | 1,070 (39.5) | 677 (37.1) | 427 (37.5) |

| Smoking status, no. (%) | ||||||

| Never | 497 (50.3) | 696 (53.1) | 2,023 (51.3) | 1,399 (51.7) | 933 (51.2) | 542 (47.6) |

| Former | 366 (37.0) | 451 (34.4) | 1,442 (36.6) | 1,015 (37.5) | 704 (38.6) | 481 (42.3) |

| Current | 122 (12.4) | 162 (12.4) | 471 (11.9) | 278 (10.3) | 171 (9.4) | 106 (9.3) |

| Median pack-years (IQR) in ever-smokers, yr | 10.0 (28.5) | 5.0 (18.8) | 9.0 (23.1) | 13.9 (27.7) | 16.0 (29.3) | 18 (33.0) |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Diabetes,* no. (%) | 57 (5.8) | 65 (5.0) | 259 (6.6) | 299 (11.1) | 265 (14.5) | 360 (31.6) |

| Hypertension,† no. (%) | 300 (30.4) | 390 (30.0) | 1,450 (36.8) | 1,339 (49.5) | 1,042 (57.2) | 835 (73.4) |

| eGFR, mean (SD), ml/min/1.73 m2 | 85.8 (20.5) | 88.0 (21.1) | 86.1 (22.6) | 81.5 (29.6) | 78.7 (21.2) | 70.9 (24.8) |

| Lung function | ||||||

| Baseline FEV1 % predicted, mean (SD), % | 100.0 (13.4) | 100.6 (15.6) | 100.6 (13.8) | 100.8 (14.9) | 101.0 (15.2) | 99.3 (15.9) |

| Baseline FEV1, mean (SD), L | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.7) |

| Baseline FVC, mean (SD), L | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.2 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.9) |

| Baseline FEV1/FVC, mean (SD), % | 77.2 (5.4) | 78.6 (5.6) | 78.1 (5.6) | 77.7 (5.7) | 77.5 (5.9) | 77.0 (6.0) |

Definition of abbreviations: CARDIA = Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults; CHS = Cardiovascular Health Study; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; FHS = Framingham Heart Study; Health ABC = Health Aging and Body Composition; IQR = interquartile range; MESA = Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Lung function analyses are restricted to cohorts with longitudinal lung function following measurement of albuminuria and participants without airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC < lower limit of normal [LLN]) or restrictive pattern (FEV1/FVC > LLN and FVC < 80%) on spirometry. In MESA, for the lung function analyses, albuminuria measured concurrently with spirometry at examinations 3 and 4 was treated as baseline.

Self-reported diabetes or fasting blood sugar levels ≥126 mg/dl or use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin.

Self-reported hypertension or systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medications.

Among 18,900 participants included in analyses of incident CLRD, baseline characteristics were similar, but participants were older and had more comorbidities and smoking history (Tables E4 and E5).

Lung Function

The mean number of spirometry measures was 1.9 over a mean of 5.7 years. Total follow-up was 87,204 person-years. Twenty-one percent of participants had three or more spirometry measures, and 56% had follow-up >5 years (Table E6). On average, FEV1 was 101% predicted and declined at 31.5 ml/yr. Average FEV1/FVC was 78%.

Greater albuminuria was associated with lower initial FEV1 and faster declines for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC (Table 2). Sequential adjustment resulted in modest attenuation of effect estimates for rates of lung function decline (Figure E3), with age having the greatest apparent confounding effect. In adjusted models, for each SD increase in ln albuminuria, there was a 2.81% greater FEV1 decline (95% CI, 0.86–4.76%; P = 0.0047), 11.02% greater FEV1/FVC decline (95% CI, 4.43–17.62%; P = 0.0011), and 15% increased hazard of incident spirometry-defined moderate-to-severe COPD (n = 245; 95% CI, 2–31%; P = 0.0214).

Table 2.

Associations between Albuminuria, Initial Lung Function, and Absolute and Relative Rates of Change in Lung Function in Adults without Prevalent Chronic Lower Respiratory Diseases

| Albuminuria Categories |

ln Albuminuria |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 mg/dl (n = 891) | 2–3 mg/dl (n = 1,226) | 3–6 mg/dl (n = 3,648) | 6–12 mg/dl (n = 2,497) | 12–30 mg/dl (n = 1,644) | ≥30 mg/dl (n = 1,055) | Per SD (95% CI) (n = 10,961) | P Value | |

| Initial | ||||||||

| FEV1, ml | Ref. | 0.65 | −1.39 | −16.80 | −25.15 | −63.47* | −22.64 (−29.86 to −15.42) | <0.0001 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | Ref. | 0.47* | 0.12 | 0.41* | 0.48* | 0.16 | 0.06 (−0.04 to 0.15) | 0.27 |

| Absolute rate of change | ||||||||

| FEV1, ml/yr | Ref. | −0.24 | −1.61 | −1.92 | −2.51* | −2.98* | −0.89 (−1.50 to −0.27) | 0.0047 |

| FEV1/FVC, % yr | Ref. | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04* | −0.06* | −0.03 | −0.02 (−0.3 to −0.01) | 0.0011 |

| Relative rate of change† | ||||||||

| FEV1, % average rate (−31.5 ml/yr) | Ref. | −0.77 | −5.12 | −6.10 | −7.94* | −9.43* | −2.81 (−4.76 to −0.86) | 0.0047 |

| FEV1/FVC, % average rate (−0.2%/yr) | Ref. | 5.59 | −10.57 | −22.09* | −38.42* | −21.21 | −11.02 (−17.62 to −4.43) | 0.0011 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; Ref. = reference.

Results exclude participants with prevalent clinical chronic lower respiratory disease, airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC < lower limit of normal [LLN]), or restriction on spirometry (FEV1/FVC > LLN, FVC < LLN) at time of albuminuria measurement. Linear mixed models predicted lung function from baseline albuminuria, time since albuminuria assessment (years), and their multiplicative interaction term, with cohort-specific unstructured covariance matrix, adjusted for time-varying height, weight, and smoking status; time-invariant age (centered), birth-year (centered), study, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, pack-years of smoking, hypertension status, hypertension medications, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker medication, diabetes status, diabetes medication, and estimated glomerular filtration rate. All time-invariant factors were modeled for both cross-sectional associations and longitudinal associations via inclusion of the covariate as well as its interaction with time since albuminuria assessment. Separate models were run using categorical (grouped quantile) and continuous (natural log–transformed albuminuria) predictors, and effect estimates were reported per category or per SD, respectively. Model fit was compared by the Akaike information criterion (AIC). For FEV1, the AIC for the categorical analysis was lower (better) than for the continuous term (295,296.8 vs. 295,509.5). For the FEV1/FVC, the AIC for the categorical analysis was higher (worse) than for the continuous term (121,725.5 vs. 121,715.7).

Statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Estimates for absolute and relative rates of change in lung function are derived from the same model. The estimates for the latter reflect the estimates for the former divided by the model-based average rate of decline in the total sample; negative values indicate greater loss of lung function.

Across albuminuria categories, associations were approximately monotonic without clear evidence of a threshold (Table 2 and Figure 1). Model fit for FEV1 was better for albuminuria categories than for ln albuminuria; however, for FEV1/FVC modeling, the converse was found.

Figure 1.

Associations between albuminuria category, longitudinal lung function, and incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease events (NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study). Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are plotted for each albuminuria category (grouped quantile). Estimates for relative rate of change are calculated as the absolute rate of change per year per albuminuria category divided by the model-based average rate of decline in the total sample; negative values represent greater loss of lung function. The models are adjusted for baseline age, birth year, height, weight, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, hypertension status, hypertension medications, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker medication, diabetes status, diabetes medication, and estimated glomerular filtration rate. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Q1 = albuminuria <2 mg/dl; Q2 = albuminuria 2–3 mg/dl; Q3 = albuminuria 3–6 ml/dl; Q4 = albuminuria 6–12 mg/dl; Q5 = albuminuria 12–30 mg/dl; Q6 = albuminuria ≥30 mg/dl.

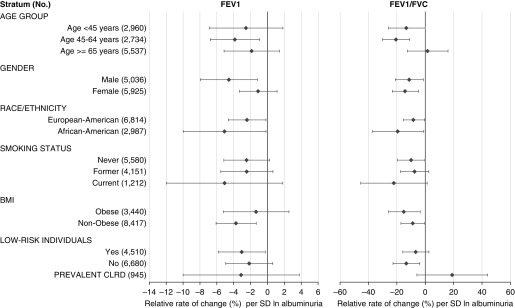

Results were similar in participants with <10 pack-years of smoking (Table E7), and even in the subset of 5,580 never-smokers (Figure 2), among whom increased albuminuria was associated, per SD, with 2.58% greater rate of FEV1 decline (95% CI, −1.7% to 5.33%; P = .0664) and 12.20% greater rate of FEV1/FVC decline (95% CI, 1.35–23.05; P = .0276) (Table E8).

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analyses for associations between albuminuria and relative rate of change in lung function (NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study). Low-risk individuals are participants without current smoking, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 at time of albuminuria measurement. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are plotted for each stratum. Estimates for relative rate of change are calculated as the absolute rate of change per year per albuminuria category divided by the model-based average rate of decline in the total sample; negative values represent greater rate of loss of lung function. Models are adjusted for baseline age, birth year, height, weight, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, hypertension status, hypertension medications, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker medication, diabetes status, diabetes medication, and eGFR. Three-way multiplicative interaction terms attained statistical significance at P < 0.05 in the FEV1 analysis for race/ethnicity, at P < 0.001 in the FEV1 analysis for sex and smoking status, and at P < 0.001 in the FEV1/FVC analysis for smoking status, body mass index, and low-risk status. BMI = body mass index; CLRD = chronic lower respiratory disease.

Associations were comparable among participants with and without prevalent CLRD, diabetes, hypertension, impaired eGFR, obesity, or cardiovascular disease (Figure 2 and Table E9). Results were consistent across cohorts, although they only attained statistical significance in FHS-Offspring and MESA (Figure E4). Fixed and random effects meta-analysis yielded similar results without evidence for substantial between-cohort heterogeneity (P = 0.25).

In women, albuminuria was strongly associated with lower initial FEV1 but not with rate of change in FEV1, whereas the opposite was observed in men (Table E10 and Figure E5). However, the additive effect of albuminuria on initial and decline in FEV1 was similar in both sexes, and there was no evidence of substantial effect modification by sex for FEV1/FVC (P-interaction = 0.12, Figure 2).

Incident CLRD Events

Median follow-up for incident CLRD events was 15 years, with 95% retention at 10 years. There were 2,269 cases of incident CLRD-related events and 554 incident severe CLRD events during 307,977 person-years. Median years to incident CLRD-related and severe CLRD events were 8 and 9, respectively. Twenty-nine percent of incident CLRD-related events and 25% of incident severe CLRD events occurred within 5 years of albuminuria measurement; 10% and 8%, respectively, occurred within 2 years.

Incidence rates increased across albuminuria categories (Table E4). For participants with albuminuria ≥30 mg/dl, the incidence rates per 10,000 person-years for CLRD-related and severe CLRD events were 125 and 26, respectively; the corresponding rates for participants with albuminuria <2 mg/dl were 68 and 13.

In adjusted models, greater albuminuria was associated with higher rates of incident CLRD-related events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11 per SD; 95% CI, 1.09–1.14; P < 0.0001) and severe CLRD events (HR, 1.08 per SD; 95% CI, 1.03–1.12; P = 0.0008). These associations were mainly due to COPD events, whereas asthma events were not significantly associated (Table 3). HRs for COPD-related events increased monotonically across albuminuria categories (Figure 1) and were somewhat attenuated but similar after adjusting for baseline FEV1/FVC (Table E11).

Table 3.

Associations of Albuminuria with Incident Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease Events during a Median of 15 Years of Follow-up (NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study)

| At Risk | Events (Cumulative Incidence) | Albuminuria Categories |

ln Albuminuria |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 mg/dl (n = 1,568) | 2–3 mg/dl (n = 1,610) | 3–6 mg/dl (n = 4,293) | 6–12 mg/dl (n = 3,091) | 12–30 mg/dl (n = 2,016) | ≥30 mg/dl (n = 1,635) | Per SD (95% CI) (n = 14,213) | P Value | |||

| CLRD events | ||||||||||

| Severe CLRD event | 14,213 | 379 (2.67) | Ref. | 1.09 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.34 | 1.52 | 1.17 (1.04–1.30) | 0.0074 |

| CLRD-related event | 14,069 | 1,414 (10.05) | Ref. | 0.97 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.25* | 1.76* | 1.23 (1.16–1.30) | <0.0001 |

| COPD events | ||||||||||

| Severe COPD event | 14,213 | 298 (2.10) | Ref. | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.66 | 1.87* | 1.23 (1.08–1.39) | 0.0013 |

| COPD-related event | 14,069 | 1,114 (7.92) | Ref. | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.34* | 1.93* | 1.26 (1.18–1.34) | <0.0001 |

| Asthma events | ||||||||||

| Severe asthma event | 14,213 | 84 (0.59) | Ref. | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 1.04 (0.81–1.35) | 0.75 |

| Asthma-related event | 14,069 | 319 (2.27) | Ref. | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 1.02 | 1.21 | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | 0.29 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; CLRD = chronic lower respiratory disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Ref. = reference.

Results exclude participants with prevalent CLRD at time of albuminuria measurement. CLRD-related events were defined as hospitalizations or deaths adjudicated as primarily or secondarily attributable to CLRD or, when adjudication was lacking, those with CLRD listed in any diagnosis field. Severe CLRD events were defined as hospitalizations or deaths adjudicated as primarily attributable to CLRD or, when adjudication was lacking, with CLRD coded as the primary discharge diagnosis or underlying cause of death. COPD and asthma events are subsets of CLRD events; there was coincidence of COPD and asthma events in certain participants. Cox proportional hazards models were used. The time to event was treated as age at event, with left truncation at age at albuminuria measurement. Non-CLRD mortality was censored. The study was treated as a stratum term, allowing for cohort-specific differences in the underlying survival function. Models were adjusted for baseline age, birth year, height, weight, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, hypertension status, hypertension medications, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker medication, diabetes status, diabetes medication, and estimated glomerular filtration rate. Separate models were run using categorical (grouped quantile) and continuous (natural log–transformed albuminuria) predictors, and effect estimates were reported per category or per SD, respectively. Model fit was compared by the Akaike information criterion (AIC). For all endpoints, the AIC for the categorical analysis was higher (worse) than for the continuous term (COPD/primary cause, 3,910.37 vs. 3,903.88; COPD/contributing cause, 14,978.94 vs. 14,967.12; asthma/primary cause, 1,170.38 vs. 1,164.38; asthma/contributing cause, 4,519.81 vs. 4,517.58).

P < 0.05.

There was no statistical evidence for effect measure modification by sex, age, obesity, or comorbidities (P > 0.05). Results were mainly similar across categories of race/ethnicity and smoking status, and significant associations with COPD-related events were demonstrated in never-smokers (HR, 1.45 per SD; 95% CI, 1.13–1.62; P < 0.0001; Figure E6). However, associations were attenuated in low-risk participants (Figure E6) and nonsignificant in the relatively small sample of participants known to be without baseline spirometric abnormalities (Table E12). Results were similar in competing risks analysis (Table E13) and using the time since albuminuria measurement as time to event (Table E14).

Discussion

Albuminuria was associated with lower lung function, accelerated lung function decline, and increased incident spirometry-defined COPD and COPD events in a large U.S. population–based sample of adults. Associations were observed across a range of albuminuria values and were independent of smoking, diabetes, and hypertension. These results provide large-scale support for the endothelial hypothesis of COPD, suggesting that further investigation is warranted into whether endothelial and microvascular mechanisms may be promising targets for COPD prevention and treatment.

Associations of albuminuria with cardiovascular and renal outcomes are well established (52, 53), yet this is the first study of which we are aware to demonstrate associations between albuminuria and prospective CLRD endpoints in a population-based sample. This suggests that shared biological mechanisms may contribute to the frequent comorbidity of diseases that are associated with prominent vascular pathologies with CLRD, a heterogeneous clinical entity for which most current medical therapies target the airways. We examined associations with all CLRD because they share risk factors, mechanisms, and therapies, and frequently overlap (54). Stronger associations with COPD events versus asthma events could reflect the relatively greater incidence of COPD among older adults, but they may also suggest greater biological relevance of endothelial dysfunction to development of COPD—inclusive of emphysema and chronic bronchitis—versus asthma.

Co-occurrence of pulmonary and renal endothelial cell injury was recently demonstrated on pathological samples in patients with COPD and cigarette-exposed mice, among whom the extent of angiopathy in both organs was correlated cross-sectionally with albuminuria (22). Beyond smoking-related microvascular damage, diabetic microangiopathy has been correlated with thickened alveolar basal laminae (55) and lower transfer coefficients for carbon monoxide, suggesting comorbid pulmonary microangiopathy (56). From a biological standpoint, ceramides, which are known to cause endothelial dysfunction, are associated with increased albuminuria in diabetics and smoking-related lung injury and emphysema (9–11, 57–59). In the present work, associations between albuminuria and adverse respiratory outcomes were independent of, and persisted in the absence of, diabetes and smoking. This suggests that, regardless of its etiology, systemic endothelial injury may be a risk factor for respiratory impairment.

Potential roles for endothelial dysfunction in COPD pathogenesis is a subject of considerable interest and ongoing investigation. Pulmonary capillary destruction has been well documented in advanced COPD and emphysema (60, 61), as have correlations between endothelial biomarkers, lung function, and emphysema on computed tomography (CT) (62, 63). Flow-mediated dilation has not demonstrated consistent associations with lung function, emphysema, or diffusing capacity (15, 16). However, magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that pulmonary microvascular blood flow is decreased even in early or mild COPD, and these changes are associated with increases in endothelial microparticles (14, 64). Our results using a population-based sample are consistent with endothelial dysfunction being a risk factor for CLRD, particularly COPD, which has both mechanistic and therapeutic implications.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) and angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) therapies are effective for preventing progression of nephropathy in persons with increased albuminuria. This effect may be mediated via inhibition of transforming growth factor-β (65), which is implicated in alveolar septation (66). ACEi/ARB use has been associated with attenuation of smoking-induced lung injury in mice (22, 67) and slower progression of emphysema on CT in adults (68). ACEis have also been shown to decrease expression of advanced glycation endproducts in pulmonary and renal endothelial cells in cigarette smoke–exposed mice and to abrogate progression of emphysema and small airway remodeling (22). There is currently a phase 4 clinical trial underway to test whether ARBs slow progression of emphysema on CT among patients with COPD (NCT02696564). Our findings support testing microvascular therapies, such as ACEi/ARB, for COPD prevention and treatment.

Strengths of this work include investigation of a biologically plausible hypothesis using a large, carefully characterized, population-based sample. This provided power for longitudinal, repeated measures analysis of lung function; adjustment for sociodemographic factors, smoking, and comorbidities; important subgroup analyses; and classification of incident spirometry-defined COPD and CLRD events during follow-up. There are nonetheless several limitations.

A pooled cohorts approach introduces heterogeneity among participants and measures. Nevertheless, measurements were frequently accomplished using similar or identical protocols. Data were systematically harmonized, and we applied current sprirometry quality control standards (31). We used statistical methods that provided flexibility for cohort-specific differences, and cohort-stratified analyses and meta-analyses yielded similar results, supporting the effectiveness of our data harmonization. The fact that cohort-stratified results mainly did not achieve statistical significance—likely due to imprecision arising out of the limited number of spirometry examinations per individual, short spirometry follow-up in certain cohorts, and relatively small magnitude of associations—highlights the value of the pooled cohorts approach.

Post-bronchodilator spirometry, which is required for the current clinical definition of COPD, was unavailable. Prebronchodilator spirometry remains nonetheless highly prognostic of health outcomes in population-based data, and it is highly correlated with post-bronchodilator measures in the general population (69, 70). Furthermore, we corroborated associations between albuminuria and lung function by analyzing validated incident clinical events.

Although an event-based definition of incident CLRD has low sensitivity, because it excludes participants who did not suffer hospitalization or mortality associated with CLRD during the follow-up period, false-negative classification would be expected to bias results toward the null (71). This may account for broadly consistent yet slightly attenuated results for the more specific endpoint, incident severe CLRD event, and attenuated results in low-risk participants.

The observed associations between albuminuria and incident COPD events could be confounded by comorbidities. Indeed, associations in low-risk participants, among whom event rates were lower, were weaker and did not attain statistical significance. Nonetheless, associations with lung function were independent of, and apparent in, participants both with and without cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes.

The prognostic significance of albuminuria for clinical CLRD events, although potentially clinically important, could not be confirmed in this general population–based study. Associations between albuminuria and FEV1 were similar in persons with prevalent CLRD, but imprecise in the context of relatively low power, suggesting that additional studies in COPD cohorts are warranted. That being said, by focusing our analyses on healthy adults without prevalent respiratory conditions, the present work mitigates standard concerns regarding reverse causality and medication-related effects.

Moreover, in demonstrating significant results in never-smokers, we may posit a mechanistic role for endothelial injury in the development of COPD independent of one of the most important causal factors and potential confounders in COPD epidemiology, cigarette exposure. Our work therefore promotes further investigation into other common causes of endothelial dysfunction, such as hypertension, metabolic syndrome, atherosclerotic disease, and physical inactivity, as risk determinants for low lung function and COPD in the general population, including in never-smokers.

Direct clinical applicability of our results may be limited. Nonetheless, albuminuria is a noninvasive measure that could be considered in selection and monitoring of high-risk participants enrolled in clinical trials of COPD prevention, if not risk stratification in the general population. Our findings also highlight clinically important and well-established associations between COPD and well-known causes of albuminuria (i.e., chronic kidney disease and diabetes) while suggesting that these comorbidities may share underlying microvascular mechanisms.

In conclusion, in a U.S. population–based sample of adults, albuminuria was associated with accelerated lung function decline and increased incident spirometry-defined COPD and COPD events. This suggests that endothelial and microvascular mechanisms are promising targets for COPD prevention and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Footnotes

Supported as follows: NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study: NIH/NHLBI R21-HL121457, R21-HL-129924, K23-HL-130627. ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) Study: The ARIC study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the NHLBI, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, HHSN268201700004I, HHSN2682017000021. CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) Study: CARDIA is conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C and HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), the University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C), and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intraagency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005), as well as an NHLBI grant (to R.K.) R01 HL122477. This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content. CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study): This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the NHLBI, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the NIA. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org. FHS (Framingham Heart Study): From the Framingham Heart Study of the NHLBI of the NIH and Boston University School of Medicine. This work was supported by the NHLBI’s Framingham Heart Study (contract no. N01-HC-25195; HHSN268201500001I). Health ABC (Health Aging and Body Composition) Study: This research was supported by NIA contracts N01-AG-6-2101, N01-AG-6-2103, and N01-AG-6-2106; NIA grant R01-AG028050; and by National Institute of Nursing Research grant R01-NR012459. MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis): NIH/NHLBI R01-HL-077612, R01-HL-093081, RC1-HL-100543, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, and N01-HC-95169. This publication was also developed under a STAR research assistance agreement, no. RD831697 (MESA Air), awarded by the U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It has not been formally reviewed by the EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and the EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication.

Author Contributions: E.C.O.: study design, data collection, data quality control and harmonization, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. P.P.B.: data collection, quality control, harmonization, and analyses. M.E.G., P.A.C., R. Kalhan, L.R.L., G.T.O’C., M.S., R.P.T., M.Y.T., and W.W.: data collection and critical review of manuscript. D.R.J.: study design, data collection, statistical plan, and critical review of manuscript. R.G.B. and S.Y.: study design, data collection, and critical review of manuscript. K.M.B.: study design and critical review of manuscript. R. Kronmal: data collection, statistical plan, and critical review of manuscript. J.E.S.: statistical plan and critical review of manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0402OC on September 28, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1341–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(293):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, Giles WH, Holt JB, Croft JB. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged ≥18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015;147:31–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, et al. 50-Year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:351–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiley J, Gibbons G. Developing a research agenda for primary prevention of chronic lung diseases—an NHLBI perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:762–763. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0380ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Le Cras TD, Abman S, Hirth PK, et al. Inhibition of VEGF receptors causes lung cell apoptosis and emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1311–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI10259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuder RM, Zhen L, Cho CY, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Salvemini D, et al. Oxidative stress and apoptosis interact and cause emphysema due to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor blockade. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:88–97. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0228OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrache I, Kamocki K, Poirier C, Pewzner-Jung Y, Laviad EL, Schweitzer KS, et al. Ceramide synthases expression and role of ceramide synthase-2 in the lung: insight from human lung cells and mouse models. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrache I, Natarajan V, Zhen L, Medler TR, Richter AT, Cho C, et al. Ceramide upregulation causes pulmonary cell apoptosis and emphysema-like disease in mice. Nat Med. 2005;11:491–498. doi: 10.1038/nm1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweitzer KS, Hatoum H, Brown MB, Gupta M, Justice MJ, Beteck B, et al. Mechanisms of lung endothelial barrier disruption induced by cigarette smoke: role of oxidative stress and ceramides. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L836–L846. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00385.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris B, Klein R, Jerosch-Herold M, Hoffman EA, Ahmed FS, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. The association of systemic microvascular changes with lung function and lung density: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle MF, Tracy RP, Parikh MA, Hoffman EA, Shimbo D, Austin JH, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomashow MA, Shimbo D, Parikh MA, Hoffman EA, Vogel-Claussen J, Hueper K, et al. Endothelial microparticles in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis chronic obstructive pulmonary disease study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:60–68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1697OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr RG, Mesia-Vela S, Austin JH, Basner RC, Keller BM, Reeves AP, et al. Impaired flow-mediated dilation is associated with low pulmonary function and emphysema in ex-smokers: the Emphysema and Cancer Action Project (EMCAP) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1200–1207. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-980OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra D, Gupta A, Strollo PJ, Jr, Fuhrman CR, Leader JK, Bon J, et al. Airflow limitation and endothelial dysfunction. Unrelated and independent predictors of atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:38–47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2093OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, Giatras I, Toto R, Remuzzi G, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:73–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent DM, Jafar TH, Hayward RA, Tighiouart H, Landa M, de Jong P, et al. Progression risk, urinary protein excretion, and treatment effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in nondiabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1959–1965. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmon AH, Ferguson JK, Burford JL, Gevorgyan H, Nakano D, Harper SJ, et al. Loss of the endothelial glycocalyx links albuminuria and vascular dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1339–1350. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmon AH, Satchell SC. Endothelial glycocalyx dysfunction in disease: albuminuria and increased microvascular permeability. J Pathol. 2012;226:562–574. doi: 10.1002/path.3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polverino F, Laucho-Contreras ME, Petersen H, Bijol V, Sholl LM, Choi ME, et al. A pilot study linking endothelial injury in lungs and kidneys in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1464–1476. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1765OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurtado A, Escudero E, Pando J, Sharma S, Johnson RJ. Cardiovascular and renal effects of chronic exposure to high altitude. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:iv11–iv16. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casanova C, de Torres JP, Navarro J, Aguirre-Jaime A, Toledo P, Cordoba E, et al. Microalbuminuria and hypoxemia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1004–1010. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0360OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon JH, Won JU, Ahn YS, Roh J. Poor lung function has inverse relationship with microalbuminuria, an early surrogate marker of kidney damage and atherosclerosis: the 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau AC, Lo MK, Leung GT, Choi FP, Yam LY, Wasserman K. Altered exercise gas exchange as related to microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetic patients. Chest. 2004;125:1292–1298. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ukena C, Mahfoud F, Kindermann M, Graber S, Kindermann I, Schneider M, et al. Smoking is associated with a high prevalence of microalbuminuria in hypertensive high-risk patients: data from I-SEARCH. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:825–832. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0194-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romundstad S, Naustdal T, Romundstad PR, Sorger H, Langhammer A. COPD and microalbuminuria: a 12-year follow-up study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1042–1050. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00160213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oelsner EC, Balte PP, Cassano P, Jacobs DR, Barr RG, Burkart KM, et al. Albuminuria is associated with lung function decline and incident severe chronic lower respiratory disease exacerbations: the NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A1015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oelsner EC, Grams ME, Jacobs DR, Kronmal R, O’Connor GT, Rabinowitz D, et al. Microalbuminuria predicts the incidence of severe chronic lower respiratory disease exacerbations in older adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)-lung study [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A6167. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oelsner EC, Balte PP, Cassano P, Couper D, Enright PL, Folsom AR, et al. Harmonization of respiratory data from nine US population-based cohorts: the NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2265–2278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study. Design and preliminary data. Prev Med. 1975;4:518–525. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(75)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodpaster BH, Carlson CL, Visser M, Kelley DE, Scherzinger A, Harris TB, et al. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: the Health ABC Study. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2001:2157–2165. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, et al. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz R, Cowan LD, Le NA, Oopik AJ, et al. The Strong Heart Study. A study of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:1141–1155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith NL, Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Tracy RP, Cornell ES. The reliability of medication inventory methods compared to serum levels of cardiovascular drugs in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller WG, Bruns DE, Hortin GL, Sandberg S, Aakre KM, McQueen MJ, et al. National Kidney Disease Education Program-IFCC Working Group on Standardization of Albumin in Urine. Current issues in measurement and reporting of urinary albumin excretion. Clin Chem. 2009;55:24–38. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.106567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers GL, Miller WG, Coresh J, Fleming J, Greenberg N, Greene T, et al. National Kidney Disease Education Program Laboratory Working Group. Recommendations for improving serum creatinine measurement: a report from the Laboratory Working Group of the National Kidney Disease Education Program. Clin Chem. 2006;52:5–18. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.0525144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hankinson JL, Kawut SM, Shahar E, Smith LJ, Stukovsky KH, Barr RG. Performance of American Thoracic Society-recommended spirometry reference values in a multiethnic sample of adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) lung study. Chest. 2010;137:138–145. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gardner RM. Standardization of spirometry: a summary of recommendations from the American Thoracic Society. The 1987 update. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:217–220. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-2-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. 10th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oelsner EC, Loehr LR, Henderson AG, Donohue KM, Enright PL, Kalhan R, et al. Classifying chronic lower respiratory disease events in epidemiologic cohort studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1057–1066. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201601-063OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, III, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, et al. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001;286:421–426. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, Bilo HJ, Chalmers J, Heerspink HJ, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:1662–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Postma DS, Rabe KF. The asthma–COPD overlap syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1241–1249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1411863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vracko R, Thorning D, Huang TW. Basal lamina of alveolar epithelium and capillaries: quantitative changes with aging and in diabetes mellitus. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:973–983. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weir DC, Jennings PE, Hendy MS, Barnett AH, Burge PS. Transfer factor for carbon monoxide in patients with diabetes with and without microangiopathy. Thorax. 1988;43:725–726. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.9.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shiffman D, Pare G, Oberbauer R, Louie JZ, Rowland CM, Devlin JJ, et al. A gene variant in CERS2 is associated with rate of increase in albuminuria in patients with diabetes from ONTARGET and TRANSCEND. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levy M, Khan E, Careaga M, Goldkorn T. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 is activated by cigarette smoke to augment ceramide-induced apoptosis in lung cell death. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L125–L133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00031.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmed FS, Jiang XC, Schwartz JE, Hoffman EA, Yeboah J, Shea S, et al. Plasma sphingomyelin and longitudinal change in percent emphysema on CT. The MESA lung study. Biomarkers. 2014;19:207–213. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2014.896414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voelkel NF, Cool CD. Pulmonary vascular involvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;46:28s–32s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voelkel NF, Gomez-Arroyo J, Mizuno S. COPD/emphysema: the vascular story. Pulm Circ. 2011;1:320–326. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.87295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ingebrigtsen TS, Marott JL, Rode L, Vestbo J, Lange P, Nordestgaard BG. Fibrinogen and α1-antitrypsin in COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2015;70:1014–1021. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oelsner EC, Pottinger TD, Burkart KM, Allison M, Buxbaum SG, Hansel NN, et al. Adhesion molecules, endothelin-1 and lung function in seven population-based cohorts. Biomarkers. 2013;18:196–203. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.762805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hueper K, Vogel-Claussen J, Parikh MA, Austin JH, Bluemke DA, Carr J, et al. Pulmonary microvascular blood flow in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. the MESA COPD study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:570–580. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-2120OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reeves WB, Andreoli TE. Transforming growth factor β contributes to progressive diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7667–7669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, Myers L, Bunton TE, Gayraud B, et al. Dysregulation of TGF-β activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:407–411. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Podowski M, Calvi C, Metzger S, Misono K, Poonyagariyagorn H, Lopez-Mercado A, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockade attenuates cigarette smoke-induced lung injury and rescues lung architecture in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:229–240. doi: 10.1172/JCI46215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parikh MA, Aaron CP, Hoffman EA, Schwartz JE, Madrigano J, Austin JHM, et al. Angiotensin-converting inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers and longitudinal change in percent emphysema on computed tomography. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Lung Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:649–658. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-317OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mannino DM, Diaz-Guzman E, Buist S. Pre- and post-bronchodilator lung function as predictors of mortality in the Lung Health Study. Respir Res. 2011;12:136. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kato B, Gulsvik A, Vollmer W, Janson C, Studnika M, Buist S, et al. Can spirometric norms be set using pre- or post-bronchodilator test results in older people? Respir Res. 2012;13:102. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barr RG, Herbstman J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA., Jr Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:965–971. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.