The modest HIV protection observed in the human RV144 vaccine trial associated antibody responses with vaccine efficacy. T follicular helper (TFH) cells are CD4+ T cells that select antibody secreting cells with high antigenic affinity in germinal centers (GCs) within secondary lymphoid organs. To evaluate the role of TFH cells in eliciting prolonged virus-specific humoral responses, we vaccinated rhesus macaques with a combined mucosal prime/systemic boost regimen followed by repeated low-dose intrarectal challenges with SIV, mimicking human exposure to HIV-1. Although the vaccine regimen did not prevent SIV infection, decreased viremia was observed in the immunized macaques. Importantly, vaccine-induced TFH responses elicited at day 3 postimmunization and robust GC maturation were strongly associated. Further, early TFH-dependent SIV-specific B cell responses were also correlated with decreased viremia. Our findings highlight the contribution of early vaccine-induced GC TFH responses to elicitation of SIV-specific humoral immunity and implicate their participation in SIV control.

KEYWORDS: T follicular helper cell, germinal center, rhesus macaque, simian immunodeficiency virus, vaccine

ABSTRACT

T follicular helper (TFH) cells are fundamental in germinal center (GC) maturation and selection of antigen-specific B cells within secondary lymphoid organs. GC-resident TFH cells have been fully characterized in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. However, the role of GC TFH cells in GC B cell responses following various simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaccine regimens in rhesus macaques (RMs) has not been fully investigated. We characterized GC TFH cells of RMs over the course of a mucosal/systemic vaccination regimen to elucidate GC formation and SIV humoral response generation. Animals were mucosally primed twice with replicating adenovirus type 5 host range mutant (Ad5hr)-SIV recombinants and systemically boosted with ALVAC-SIVM766Gag/Pro/gp120-TM and SIVM766&CG7V gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum hydroxide (ALVAC/Env) or DNA encoding SIVenv/SIVGag/rhesus interleukin 12 (IL-12) plus SIVM766&CG7V gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum phosphate (DNA&Env). Lymph nodes were biopsied in macaque subgroups prevaccination and at day 3, 7, or 14 after the 2nd Ad5hr-SIV prime and the 2nd vector/Env boost. Evaluations of GC TFH and GC B cell dynamics including correlation analyses supported a significant role for early GC TFH cells in providing B cell help during initial phases of GC formation. GC TFH responses at day 3 post-mucosal priming were consistent with generation of Env-specific memory B cells in GCs and elicitation of prolonged Env-specific humoral immunity in the rectal mucosa. GC Env-specific memory B cell responses elicited early post-systemic boosting correlated significantly with decreased viremia postinfection. Our results highlight the importance of early GC TFH cell responses for robust GC maturation and generation of long-lasting SIV-specific humoral responses at mucosal and systemic sites. Further investigation of GC TFH cell dynamics should facilitate development of an efficacious HIV vaccine.

IMPORTANCE The modest HIV protection observed in the human RV144 vaccine trial associated antibody responses with vaccine efficacy. T follicular helper (TFH) cells are CD4+ T cells that select antibody secreting cells with high antigenic affinity in germinal centers (GCs) within secondary lymphoid organs. To evaluate the role of TFH cells in eliciting prolonged virus-specific humoral responses, we vaccinated rhesus macaques with a combined mucosal prime/systemic boost regimen followed by repeated low-dose intrarectal challenges with SIV, mimicking human exposure to HIV-1. Although the vaccine regimen did not prevent SIV infection, decreased viremia was observed in the immunized macaques. Importantly, vaccine-induced TFH responses elicited at day 3 postimmunization and robust GC maturation were strongly associated. Further, early TFH-dependent SIV-specific B cell responses were also correlated with decreased viremia. Our findings highlight the contribution of early vaccine-induced GC TFH responses to elicitation of SIV-specific humoral immunity and implicate their participation in SIV control.

INTRODUCTION

T follicular helper (TFH) cells are specialized CD4+ T cells that provide help to cognate B cells in the follicles of secondary lymphoid organs through ligand-receptor interactions and soluble factors. Such interactions are fundamental for promoting germinal center (GC) expansion, B cell maturation to antibody-secreting cells (ASC), and generation of high-affinity antibodies, including broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) (1, 2). Key interactions between TFH cells and follicular B cells include CD40-CD40L, PD-1–PDL-1, and T cell receptor (TCR)-major histocompatibility complex (MHC), among others (3, 4). The major soluble factor involved in TFH-B cell communication is the cytokine interleukin 21 (IL-21), which is well established as necessary for regulation of GC maturation, affinity selection of B cells, differentiation of B cells into specific memory and plasma cell populations within GCs, and induction of IgG1 class switch recombination in human B cells (5).

The development of an effective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vaccine has been hampered by the enormous diversity of the virus and its ability to escape host immune defenses. Hence, development of bNAbs against HIV-1, believed to be important for protective efficacy, is a challenging process for the human immune system. Within GCs, B cells proliferate and undergo somatic hypermutation (SHM), resulting in generation of mutant clones that have a plethora of affinity levels for the immunizing antigen (Ag) (6). Extensive rounds of SHM and affinity selection of B cells are required for bNAb generation (7).

Antibody-mediated immunity against HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) relies on signals provided by GC resident TFH cells (8–11). A study using the rhesus macaque simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) model showed that frequency and quality of Env-specific TFH cells within GCs of SHIV-infected animals are important for bNAb development (10), reinforcing the concept of association of GC TFH cells with generation of robust SHIV humoral responses.

Previously, we demonstrated that mucosal priming with replication-competent adenovirus type 5 host range mutant (Ad5hr) recombinants encoding SIV Env combined with systemic Env boosting elicited persistent humoral immunity (12). We also detected a population of IL-21-producing Env-specific TFH cells in lymph nodes (LNs) of rhesus macaques enrolled in a preclinical vaccine trial (13). The abundance of these cells was directly associated with mucosal and systemic SIV-specific humoral responses, emphasizing the relevance of IL-21-secreting SIV-specific TFH cells in the development of humoral responses against SIV/HIV. However, little is known about the longevity of SIV-specific, vaccine-induced TFH cells and the dynamics whereby TFH and GC B cell interactions lead to generation of efficient SIV-specific humoral responses.

In this study, rhesus macaques were vaccinated by mucosal priming with replicating Ad-SIV recombinants followed by systemic boosting with either ALVAC-SIVM766Gag/Pro/gp120-TM and SIVM766&CG7V gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum hydroxide (ALVAC/Env) or DNA encoding SIVenv/SIVGag/rhesus IL-12 plus SIVM766&CG7V gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum phosphate (DNA&Env). We chose the Ad-SIV recombinant priming strategy in order to elicit strong mucosal immunity (14). The ALVAC/Env booster regimen was chosen because it was used in the RV-144 clinical HIV vaccine trial, which achieved modest protection (15), and a similar regimen using ALVAC-SIV recombinants and SIV proteins elicited protection of rhesus macaques against SIVmac251 acquisition following low-dose challenge exposure (16, 17). Additionally, the ALVAC/Env boost induced elevated numbers of IL-21+ HIV-specific peripheral TFH cells in comparison to ALVAC alone or a DNA/Ad5 regimen (18). The DNA&Env booster was chosen as administration of optimized DNA vectors together with purified SIV Env proteins elicited long-lasting, high levels of functional humoral immune responses in plasma and at mucosal sites (19). Using LN biopsy specimens collected from macaque subgroups at distinct time points over the course of immunization, we examined response kinetics and investigated interactions between TFH and GC B cells leading to GC maturation and development of SIV-specific humoral responses. Our goal was to elucidate TFH cell function and the impact of TFH cell frequency and longevity on elicitation of SIV-specific B cell responses over the course of the mucosal/systemic immunization regimen.

RESULTS

Phenotypic analysis of GC TFH cells and Ag-specific TFH cells.

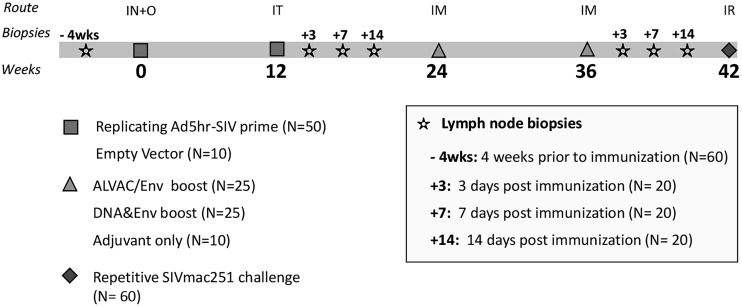

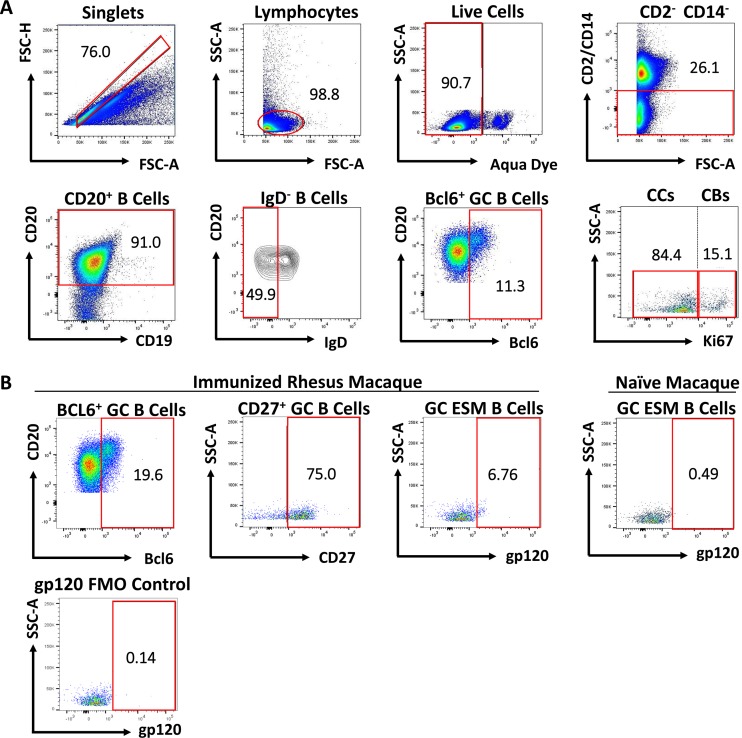

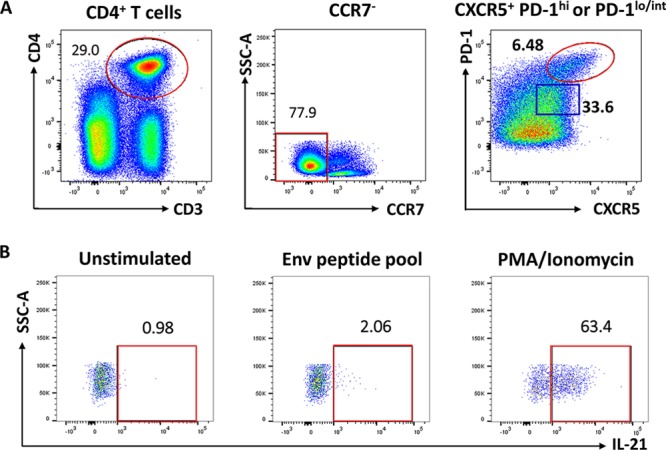

To clarify the role of TFH cells in coordinating GC B cell responses over the course of immunization, we collected LN biopsy specimens prior to immunization and at days 3, 7, and 14 postimmunization in defined subgroups of macaques after the second mucosal priming immunization at week 12 and after the second booster immunization at week 36 (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1). These time points surrounded the reported time of peak GC maturation (day 7), following antigen exposure (6). The inclusion of LN collections at day 3 postimmunization allowed us to investigate dynamics of TFH and B cell subsets in GCs during initial phases of GC maturation, which have not been fully elucidated in macaques. We first detected and quantified LN TFH cells based on canonical phenotypic markers involved in their differentiation (20). Upon dendritic cell (DC) priming, antigen-specific T cells downregulate the localization marker CCR7 and upregulate CXCR5, which favors migration toward the B cell zone (8, 21, 22). Therefore, TFH cells were first gated on CD4+ CD3+ CCR7− T cells to exclude extrafollicular T cells (Fig. 2A). In addition to CXCR5 expression, high levels of PD-1 expression are required for GC TFH identification (22, 23). Thus, resident GC TFH cells were characterized as CXCR5+ PD-1hi, gated on CCR7− CD4+ CD3+ T cells (Fig. 2A). IL-21-producing TFH cells are critical for GC initiation and continuous maturation of memory B cells within GCs (24, 25). Therefore, identification of SIV gp120-specific TFH cells was based on IL-21 expression following stimulation with SIV envelope peptide pools (Fig. 2B) as previously described (13).

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of immunization protocol. Fifty rhesus macaques were primed at weeks 0 and 12 with (Ad5hr)-SIVM766gp120-TM and Ad5hr-SIV239Gag. Immunized macaques were divided into two groups and boosted at weeks 24 and 36 with ALVAC/Env (ALVAC-SIVM766Gag/Pro and SIVM766&CG7V gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum hydroxide) or DNA&Env (DNA with SIVenv/SIVGag/rhesus IL-12 plus SIVM766&CG7V gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum phosphate). The control group (n = 10) received empty Ad5hr vector at priming and adjuvant only at boosting. At week 42, weekly repeated low-dose SIVmac251 challenges of all animals were initiated. Inguinal LNs were sampled 4 weeks prior to the first immunization. Three groups of animals had LN biopsy specimens collected, respectively, at days 3, 7, and 14 after the second prime and after the second boost. IN, intranasal; O, oral; IT, intratracheal; IM, intramuscular; IR, intrarectal.

FIG 2.

Phenotypic and functional characterization of GC-resident T follicular helper (TFH) cells in immunized rhesus macaques. (A) GC TFH cells were defined as CCR7− CXCR5+ PD-1hi (red gate), gated on the CD4+ CD3+ T cell population. CCR7− CXCR5+ PD-1low/int cells (blue gate) were classified as non-GC TFH cells. (B) IL-21+ Env-specific GC TFH cells were identified after stimulation with Env pooled peptides. Unstimulated cells were used for gate definition of stimulated cells. PMA-ionomycin stimulation was performed as a positive control for cytokine release.

Some ligand-receptor interactions between TFH and follicular B cells are required for GC development (26). B cell help provided by TFH cells is dependent on CD40L, PD-1, and ICOS (1, 4, 8). CD40-CD40L signaling between TFH and GC B cells enables TFH cells to activate activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B cells, necessary for immunoglobulin affinity maturation (27). Hence, CD40L+ cells were evaluated to confirm the B cell help potential of GC TFH cells. The average proportion of CD40L+ GC TFH cells 3 days following both the second mucosal prime and the second systemic booster immunizations was 40.58%, significantly increased in comparison to the average frequency (6.4%) of non-TFH cells (CCR7− CXCR5− PD-1−) at the same time points. Frequencies of CD40L expression on non-GC TFH cells (CCR7− CXCR5+ PD-1low/int) at day 3 following the immunizations were also lower than for the GC TFH subset, varying between 1 and 24.2%, indicating a lesser potential to provide B cell help.

Human CXCR5+ TFH cells are also phenotypically characterized by high levels of CD95, particularly on activated effector T cells. In this study, CD95 was consistently expressed on CXCR5+ PD-1hi T cells, with an average frequency of 99.8%, significantly higher than that on non-TFH cells (average of 57.7%), consistent with the GC TFH cell phenotype.

Detection of GC B cells and Ag-specific GC B cells.

GC B cells were identified as illustrated in Fig. 3A and as previously reported (13, 28). T cell-dependent GC responses lead to IgG, IgA, or IgE memory B cells expressing CD27 and lacking IgD, indicating that they have undergone class switch recombination (CSR) and SHM (29). CD27-negative memory B cells represent a restricted LN subset in rhesus macaques and decrease dramatically over the course of immunization with development of CD27+ resting and activated memory B cell responses (30). Hence, SIV-specific memory B cells were gated on CD27+ cells prior to gp120 gating (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Gating strategy for identification of GC B cells, centroblasts (CBs), centrocytes (CCs), and GC Env-specific memory (ESM) B cells. (A) The follicular B cell population was defined as CD20+. GC B cells were defined as CD20+ IgD− BCL6+. CBs were gated on GC B cells and defined as CD20+ BCL-6+ Ki67hi; CCs were defined as CD20+ BCL-6+ Ki67low/int/neg. (B) GC ESM B cells were gated on the GC B cell population and identified as CD27+ gp120+. The percentage of the GC ESM B cells depicted is based on frequency of the parent population (CD27+ B cells). Positive staining thresholds were set with fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls.

Vaccination effect on GC TFH dynamics.

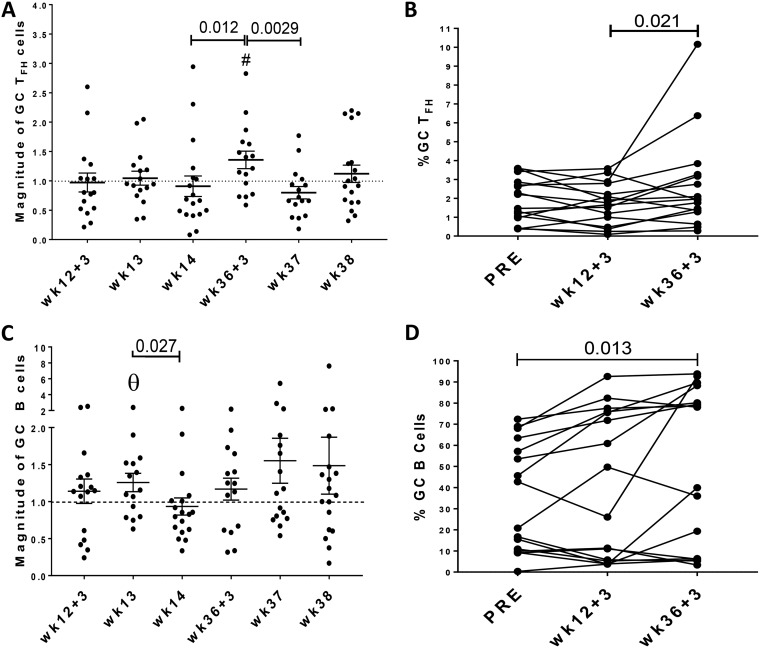

Within secondary lymphoid organs, DC-primed antigen-specific T cells upregulate ICOS, PD-1, and CXCR5, acquiring the TFH phenotype and migrating into the B cell follicle. There, interaction with cognate B cells promotes further differentiation into GC TFH cells along with higher expression levels of PD-1, a process that provides fundamental signals for GC formation and survival of antigen-specific B cells within the GCs (4, 31). For evaluation of the frequency of GC TFH cells (CD4+ CCR7− CXCR5+ PD-1hi) over the course of vaccination, LNs from three defined subgroups of macaques were investigated at specific times postimmunization (Fig. 1). In order to compare responses across the 3 time points, percentages obtained were normalized to preimmunization levels and cellular frequencies were reported as the magnitude of response. Analysis of vaccine-derived GC TFH abundance revealed no difference compared to preimmunization values and little change at the time points following the second Ad mucosal immunization (Fig. 4A). However, levels at day 3 following the second boost (week 36 + 3) were significantly higher than prevaccine levels (P = 0.039) and also significantly elevated compared to week 14 values, indicating a vaccine effect. A comparison of paired, nonnormalized GC TFH levels within the macaque subgroup that had LN biopsy specimens collected at day 3 following both immunizations revealed a significant difference between values at week 12 + 3 and week 36 + 3 (P = 0.021), consistent with an early systemic boosting effect (Fig. 4B). The elevated GC TFH frequencies were transient, as evidenced by the significant drop of the PD-1hi TFH population between the week 36 + 3 and week 37 time points (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Evaluation of GC-resident TFH and GC-resident B cells in LNs of vaccinated rhesus macaques over the course of immunization. (A) Analysis of GC resident TFH (CXCR5+ PD-1hi CD4+ T cells) cells over the course of immunization. Because LN biopsy specimens were collected from three different groups of macaques, respectively, at day 3, 7, and 14 after each immunization, percentages of GC TFH cells were normalized to preimmunization frequencies and levels are reported as magnitude of response. Comparisons were performed by the Mann-Whitney test. (B) Comparison of GC TFH cell nonnormalized percentages of paired samples from macaques with LNs collected at day 3 following immunization using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (C) Analysis of the magnitude of response of GC B cells. GC B cell responses were normalized to preimmunization frequencies and comparisons were assessed by the Mann-Whitney test. (D) Comparison of GC B cell nonnormalized percentages of paired samples from macaques with LN collected at day 3 following immunizations using the Wilcoxon signed-rank Test. T cell and B cell levels are shown as means and SEMs. #, P = 0.039 compared to the preimmunization value; Θ, P = 0.073 compared to the preimmunization value.

We next sought to quantify vaccine-induced SIV-specific TFH cells within GCs by assessing IL-21 production in CXCR5+ PD-1hi TFH cells following stimulation with pooled Env peptides (Fig. 2B). The absolute GC resident TFH cell population represented a limited fraction of the LN CD4+ CD3+ T cells in animals that had LN biopsy specimens collected at days 3, 7, and 14 postboost, ranging from 0.28 to 10.16%, 0.30 to 5.43%, and 0.048 to 8.92%, respectively. Furthermore, identification of SIV-specific GC TFH cells by intracellular cytokine production was not robust, as few macaques produced detectable IL-21+ GC TFH cells following stimulation with either SIVM766 or SIVCG7V pooled gp120 peptides (data not shown). Previous studies indicated that less than 50% of PD-1+ TFH cells are IL-21 producers (32). Moreover, conventional intracellular cytokine staining failed to identify gp140-specific GC TFH cells in a recent study (33). This issue is discussed further below.

Vaccination effect on GC B cell dynamics.

Development of specific humoral immunity depends on GC reactions during which somatically hypermutated high-affinity memory B cells and plasma cells rely on TFH cells for survival. In this study, the elevated GC TFH cells 3 days after administration of an Env immunogen suggested the ability to induce a GC reaction. To further explore the effect of vaccination on GC formation, B cell expansion, and generation of SIV-specific B cell responses, we investigated GC B cell subsets at the same time points as assessed for the GC TFH populations. Similar to GC TFH cell analysis, all B cell subpopulations were normalized to preimmunization levels in order to compare frequencies across all time points and reported as the magnitude of response. The abundance of GC B cells was somewhat higher 3 days after the second Ad prime, with a slightly higher but still nonsignificant increase at week 13 (P = 0.073 compared to the preimmunization value [Fig. 4C]). A significant decrease was seen at week 14 (P = 0.027; [Fig. 4C]). The magnitudes of GC B cell responses 3 days post-Ad and postboost were similar. Responses increased at weeks 37 and 38, but the differences observed were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, evaluation of nonnormalized paired values of samples from macaques in the day 3 subgroup showed that GC B cell frequencies at day 3 following the boost immunization were significantly elevated above the preimmunization value (P = 0.013 [Fig. 4D]). The GC TFH and B cell dynamics suggested that systemic Env boosting more efficiently induced GC responses than did the mucosal Ad-SIV immunization. Taken together, our data are consistent with previous findings in mice that expansion of precursor B cells in GCs takes place 1 to 4 days following antigen exposure (34).

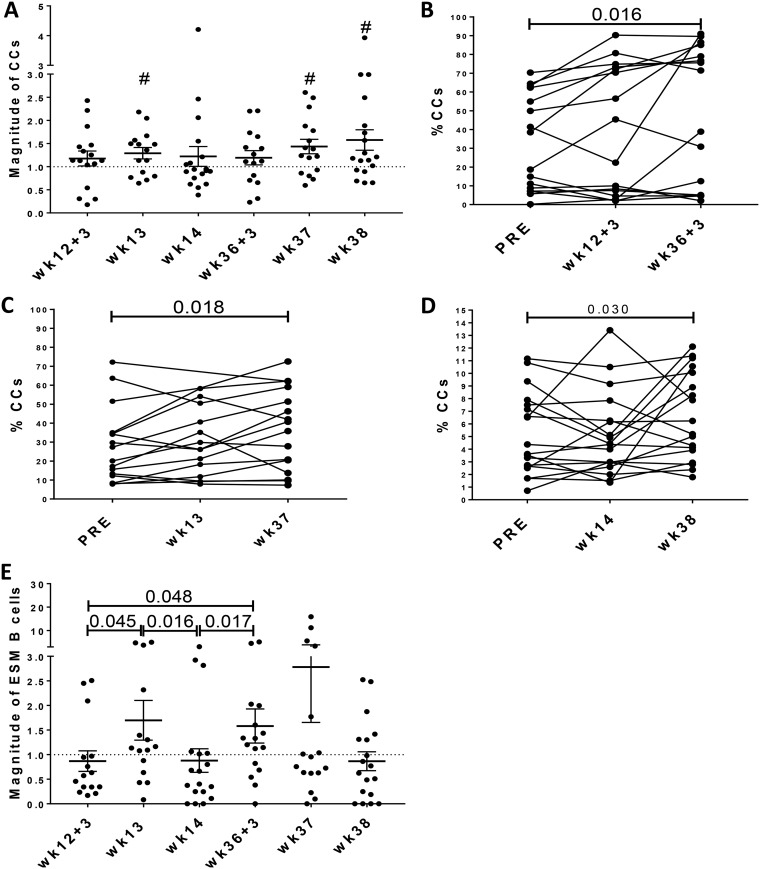

Vaccination effects on GC B cell subpopulations.

GC B cells cycle between the dark zone (DZ) and the light zone (LZ) during antibody affinity maturation. Proliferating DZ B cells, called centroblasts (CBs; BCL-6+ Ki67hi GC B cells), represent expanded, activated B cells in the initial GC maturation stage. LZ B cells, called centrocytes (CCs; BCL-6+ Ki67low/int/neg GC B cells), are selected based on their antigen affinity and show low proliferation rates (35). To further assess vaccine-induced GC maturation, CBs and CCs were evaluated over the course of immunization using postimmunization values normalized on preimmunization levels. CB responses tended to peak at day 3 after both the second prime and second boost, but these levels were not significantly higher than preimmunization levels (data not shown). In contrast, CCs exhibited a modestly increased frequency at week 13 (P = 0.035) and progressive increases at weeks 37 and 38 (P values of 0.018 and 0.027, respectively [Fig. 5A]) compared to preimmunization values. Analysis of nonnormalized CC frequencies in each of the LN subgroups supported these results, showing significant elevations at 3 days (P = 0.016), 1 week (P = 0.018), and 2 weeks (P = 0.030) following the 2nd boost (Fig. 5B to D). These increases suggest that the trend in GC B cell increases observed at weeks 37 and 38 (Fig. 4C) was associated with formation of mature GCs. Together, these results are consistent with robust GC reactions following mucosal and systemic vaccine administrations leading to progressive maturation of GCs, particularly following the 2nd systemic immunization.

FIG 5.

Evaluation of GC B cell subsets in LNs of rhesus macaques over the course of immunization. (A) Analysis of CCs (defined as CD20+ BCL-6+ Ki67low/Int/neg) over the course of immunization. Percentages of cellular populations were normalized to preimmunization frequencies as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Nonnormalized frequencies of CCs were used for paired comparisons at day 3 (B), day 7 (C), and day 14 (D) following each immunization using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (E) SIVM766 Env-specific memory (ESM) B cells were normalized to preimmunization frequencies, and comparisons were performed by the Mann-Whitney test. B cell levels are shown as means and SEMs. #, P values of 0.035, 0.018, and 0.027 at weeks 13, 37, and 38, respectively, compared to the preimmunization levels.

We next evaluated generation of SIV Env-specific memory (ESM) B cells by the vaccine regimen. ESM B cells peaked at week 13 (P = 0.045 compared to week 12 + 3 [Fig. 5E]), 7 days after the Ad-SIV recombinant administration, in agreement with the kinetics of antigen-specific GC B cell responses induced by Ad vector immunization as previously reported (36). This peak was followed by a decrease at week 14 (P = 0.016) and subsequent rebound at day 3 following the second boost immunization. The ESM B cell levels at day 3 postboost were significantly higher than levels at week 14 (p = 0.017) and also than levels at day 3 post-Ad immunization (P = 0.048 [Fig. 5E]), indicating that the booster immunization was more efficient at eliciting early SIV-specific GC responses.

Vaccination-induced TFH responses support GC formation and generation of SIV-specific responses in GC.

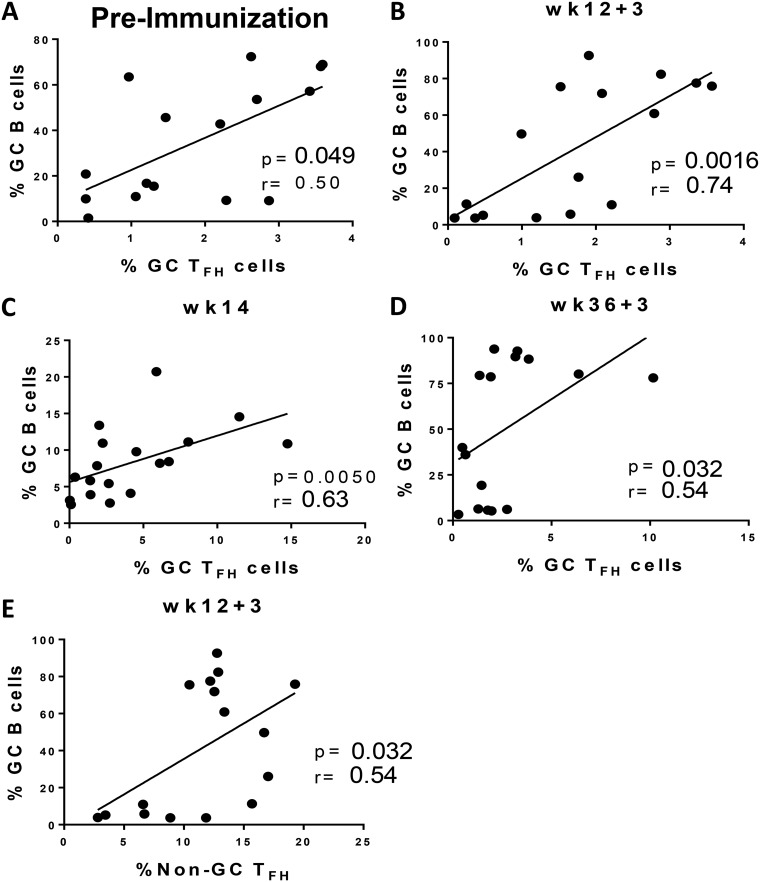

To investigate the role of GC TFH cells in vaccine-induced GC maturation, GC TFH cell frequencies were correlated with frequencies of distinct GC B cell populations at early and late time points (days 3 and 14) following the prime and boost immunizations. Initially we examined associations between GC TFH and GC B cells prior to immunization. A marginally positive correlation was observed (r = 0.50; P = 0.049) and was not unexpected, as the cell populations represented ongoing immune responses to a spectrum of environmental antigens (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, a significant positive association was found between the abundance of GC TFH and GC B cells at day 3 after the 2nd Ad priming immunization (r = 0.74, p = 0.0016; Fig. 6B), much stronger than the baseline correlation (Fig. 6A), indicating a response to immunization. A positive correlation was also observed at week 14 (Fig. 6C). Likewise, the correlation between GC TFH and GC B cell frequencies was significantly positive at day 3 after the 2nd boost (Fig. 6D) but not at week 38 (data not shown). The strongest positive correlation between GC TFH and GC B cell frequencies was observed at day 3 following the Ad mucosal immunization, validating the ability of Ad-SIV recombinant vaccines to elicit quick humoral responses (12, 14). Notably, we also found a significant positive correlation between non-GC TFH cells and GC B cells (Fig. 6E) at the week 12 + 3 time point, indicating B cell help can be provided by other TFH cell subsets. Previously we demonstrated a positive association between GC B cells and TFH cells 2 weeks following a booster vaccination (13). In this study, we demonstrated a much earlier association, at day 3 following both mucosal and systemic immunizations, highlighting the importance of GC TFH cells in providing help to B cells in the formation of the early GC.

FIG 6.

Correlations between TFH cells and GC B cells. (A to D) GC TFH and GC B cell correlations assessed 4 weeks prior to 1st prime immunization in macaques with LNs collected 3 days postimmunizations (A), day 3 following the 2nd prime (B), 2 weeks following 2nd prime (week 14) (C), and day 3 following the 2nd boost (D). (E) Correlation between non-GC TFH cells and GC B cells at day 3 following the 2nd Ad-SIV immunization. The Spearman rank correlation test was used to assess immunological correlates.

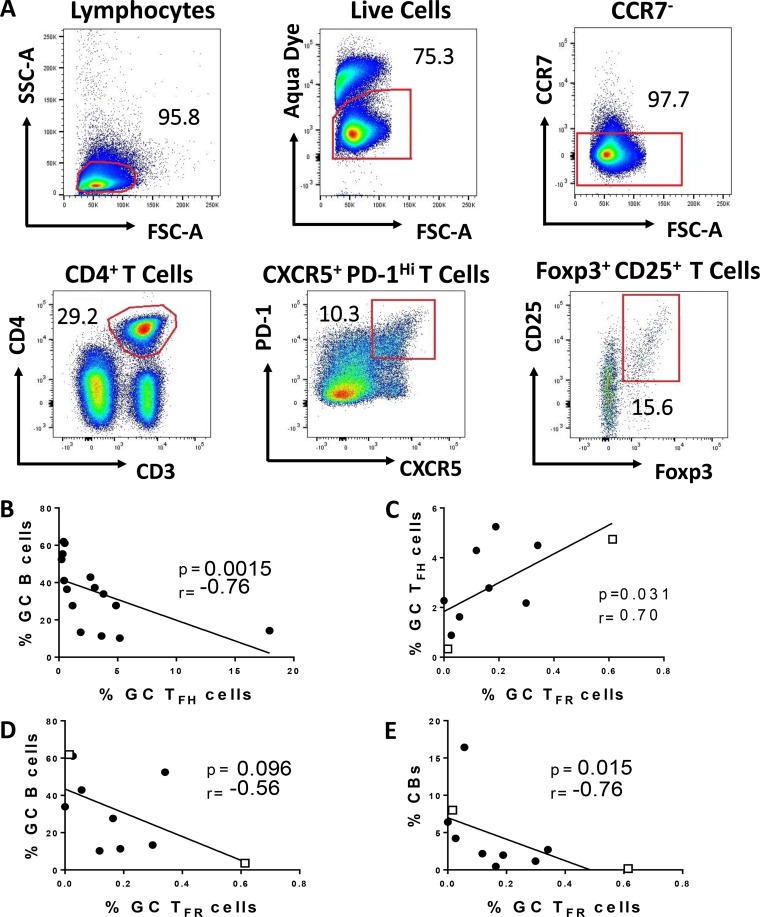

Intriguingly, while correlations at days 3 and 14 after the Ad prime were significantly positive (Fig. 6B and C), a strong negative correlation was found at week 13 (P = 0.0015; r = −0.76), 7 days following the mucosal prime (Fig. 7B). T follicular regulatory (TFR) cells have been identified as the main regulators of GC TFH activity during GC formation (37–39). Furthermore, although TFR and TFH cells are phenotypically distinct, the two subsets form under the same developmental signals (38). As TFR cells were shown to abrogate cytokine production by TFH cells (40), we questioned whether TFR cells could affect the ability of TFH cells to induce GC B cells at week 13. Correlation analyses of GC TFR cells (PD-1hi CXCR5+ CD25+ Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells [Fig. 7A]) from LNs collected at day 7 post-Ad-SIV immunization were conducted with GC TFH cells, GC B cells, and CBs from same time point. As only eight LN samples were available for TFR cell assessment, samples from two control macaques that had received empty Ad5 vector immunizations were included to increase statistical power. Although GC TFR frequencies positively correlated with the abundance of GC TFH cells (P = 0.031; r = 0.70 [Fig. 7C]), as also shown previously in SIV-infected macaques (41), GC TFR frequencies showed a trend toward an inverse correlation with GC B cells (P = 0.096; r = −0.56 [Fig. 7D]) and a significant negative correlation with CBs (P = 0.015; r = −0.76 [Fig. 7E]). Taken together, these data indicate that Ad immunization may have induced TFR responses which did not affect GC TFH frequency but impacted GC TFH function in supporting GC reactions at day 7 postvaccination. Future studies are needed to understand the differential dynamics between GC TFH and GC TFR cells which could explain the rapid changes in associations between GC TFH and GC B cells.

FIG 7.

Associations of GC T follicular regulatory (TFR) cells and GC TFH cells. (A) Representative gating strategy of GC resident TFR cells, defined as PD-1hi CXCR5+ CD25+ FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells. (B) Correlation between GC TFH cells and GC B cells at week 13 in macaques with LNs collected 7 days postimmunization. (C) Correlation between GC TFR cells and GC TFH cells at week 13. (D) Correlation trend between GC TFR and GC B cells at week 13. (E) Correlation between GC TFR cells and CBs at week 13. Control samples (recipients of empty Ad vector) added to obtain statistical power are represented by squares. The Spearman rank correlation test was used to assess immunological correlates.

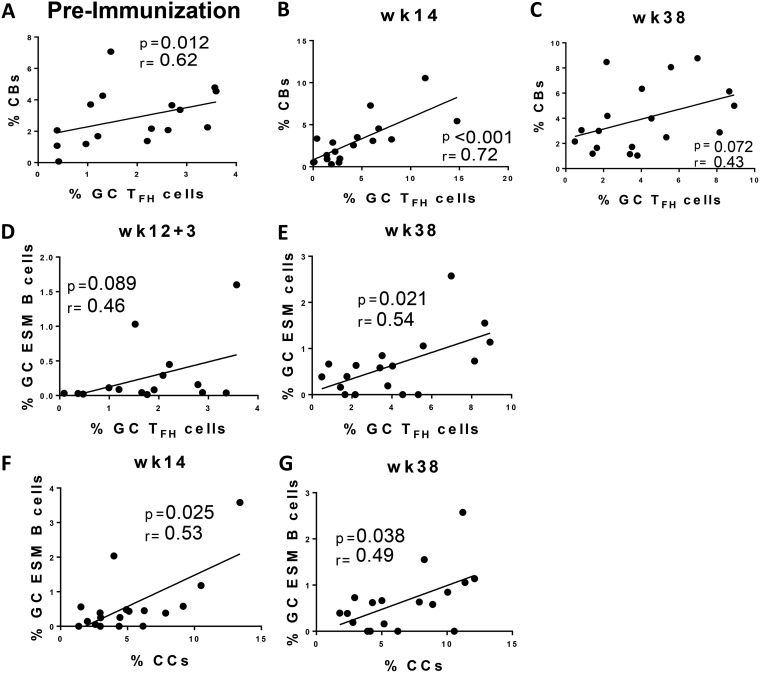

To further investigate the role of GC TFH cells in supporting GC expansion, correlations between GC TFH cells and CBs were performed prior to immunization and at days 3 and 14 postimmunization. Similar to the preimmunization association between GC TFH and GC B cells, a significant correlation was also observed between GC TFH cells and CBs (r = 0.62; P = 0.012 [Fig. 8A]) representing ongoing immune responses to environmental immunogens. A trend toward significance was observed at day 3 after the second Ad immunization (data not shown), and a highly significant correlation was observed at week 14 (Fig. 8B), consistent with induction of GC TFH-dependent B cell proliferation 2 weeks following Ad5hr-SIV recombinant priming. No significant correlation between GC TFH and CBs was seen at day 3 after the 2nd boost, but a trend toward significance was observed at week 38 (Fig. 8C), suggesting GC TFH cells also participated in GC B cell proliferation 2 weeks after the systemic boost.

FIG 8.

Correlation analyses of GC TFH cells and GC B cell subpopulations. Correlations between GC TFH cells and CBs 4 weeks prior to 1st prime immunization in macaques with LNs collected 3 days postimmunization (A), 2 weeks following 2nd prime (week 14) (B), and 2 weeks following the second boost (week 38) (C). (D and E) Correlation analyses of GC TFH cells and GC SIV ESM B cells at day 3 following the 2nd prime (D) and 2 weeks following the 2nd boost (week 38) (E). (F and G) Correlations between CCs and ESM B cells 2 weeks following the 2nd prime (week 14) (F) and 2 weeks following 2nd boost (week 38) (G). The Spearman rank correlation test was used to assess immunological correlates.

Memory B cells can be generated either inside or outside GCs. Nevertheless, GC-dependent memory B cells receive help from GC TFH cells, which leads to generation of B cells with higher antigen affinity and the ability to persist over long periods (42, 43). To assess the participation of GC TFH cells in the generation of SIV ESM B cells, we examined relationships between GC TFH and GC ESM B cell frequencies at days 3 and 14 following immunizations. Correlations prior to immunization were not observed, of course, as the macaques had not yet been exposed to SIV Env antigen. The percentages of GC TFH and ESM B cells at day 3 following the 2nd Ad-SIV prime exhibited a slight positive trend (Fig. 8D), consistent with GC TFH cell support of GC ESM responses early after mucosal priming. However, no correlation was seen at week 14, and overall the magnitude of TFH responses following the Ad immunizations was very low (Fig. 4A). In contrast, a significant correlation was seen between GC TFH cells and GC ESM B cells at week 38 (Fig. 8E), 2 wks postboost, suggesting provision of B cell help. As we were unable to detect an SIV Env-specific GC TFH cell subpopulation by IL-21 intracellular cytokine staining, results from this analysis must be interpreted with caution since the lack of correlation might indicate that GC TFH cells are not the best population for assessing TFH support of SIV ESM B cell development within GCs.

CCs are GC B cells that mature into antigen-specific memory B cells or plasma cells based on high-affinity binding to the immunizing antigen and TFH clonal selection (44, 45). To better address the nature of GC Env-specific humoral responses and its origins in CC selection, we performed correlations between CCs and GC ESM B cells. Not surprisingly, CC frequencies did not correlate with GC ESM B cells at day 3 following either the Ad-SIV recombinant priming or protein boosting, as CCs have been reported to appear within 5 to 6 days, but not as early as day 3, after antigen exposure (6). Importantly, however, GC ESM B cell and CC frequencies significantly correlated at week 14 (Fig. 8F) and week 38 (Fig. 8G), 2 weeks after both the prime and boost immunizations. Taken together, these results strongly support the CC origin of vaccine-induced GC Env-specific responses and the active cooperation of GC TFH cells in generation of ESM B cells.

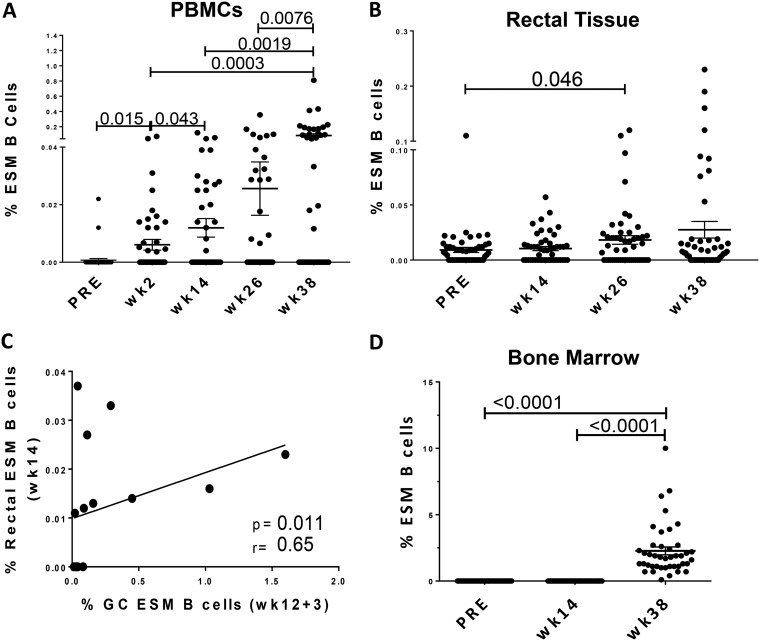

Early GC responses correlate with systemic and mucosal SIV-specific humoral responses.

Because GC ESM B cell levels tended to decrease in GCs within14 days following immunization (Fig. 5E), we postulated that this cell population might leave GCs and traffic to other sites. Therefore, we quantified ESM B cells in different tissues, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), rectal mucosa, and bone marrow, over the course of immunization. In support of our hypothesis, we observed a significant increase of ESM B cell levels in PBMCs 2 weeks after both the first and second Ad-SIV recombinant prime immunizations, weeks 2 and 14, respectively (P = 0.015; P = 0.043), with an even greater significant increase seen at week 38 (P = 0.0076 [Fig. 9A]), suggesting entry of GC ESM B cells into the circulation. Of note, increases of ESM B cells at week 14, week 26, and week 38 were also statistically significant in comparison to the preimmunization time point (P < 0.001 for each). An increase of SIVM766 ESM B cells was also observed in the rectal mucosa 2 weeks after the first boost at week 26, with even higher levels seen at week 38, suggesting migration of GC ESM B cells to the mucosal compartment (Fig. 9B). We observed a significant positive correlation between GC ESM B cells at day 3 following the second mucosal priming and rectal ESM B cells at week 14 (Fig. 9C), suggesting the GC origin of the ESM response. Collectively, our results not only indicate efficient induction of Env-specific humoral responses in the rectal mucosa by the Ad-SIV recombinant mucosal prime but also highlight the importance of early generation of GC memory B cells for long-lasting antigen-specific mucosal B cell responses.

FIG 9.

Analysis of ESM B cells in various tissues. (A and B) Frequency of SIVM766 gp120 ESM B cells in PBMCs (A) and rectal mucosa (B) over the course of immunization in all immunized animals. (C) Correlation between GC ESM B cells at day 3 after the 2nd Ad5hr-SIV prime and ESM B cells in the rectal mucosa at week 14 after the Ad5hr-SIV prime. (D) Levels of IgG-positive SIVM766 ESM B cells before and 2 weeks after the 2nd prime and 2nd boost immunizations as assessed by ELISpot assay. Data are means and SEMs.

In the bone marrow compartment, IgG secreting ESM B cell responses were observed at week 38, whereas no responses were observed at week 14 (Fig. 9D), indicating that only the boost immunization led to SIV ESM B cells in this compartment. Our analysis suggests that the Ad prime was pivotal in inducing early Env-specific responses in the mucosa, whereas the Env protein booster played a crucial role in supporting Env-specific humoral responses in the systemic compartments. Overall, the mucosal and systemic responses seemed to be GC derived.

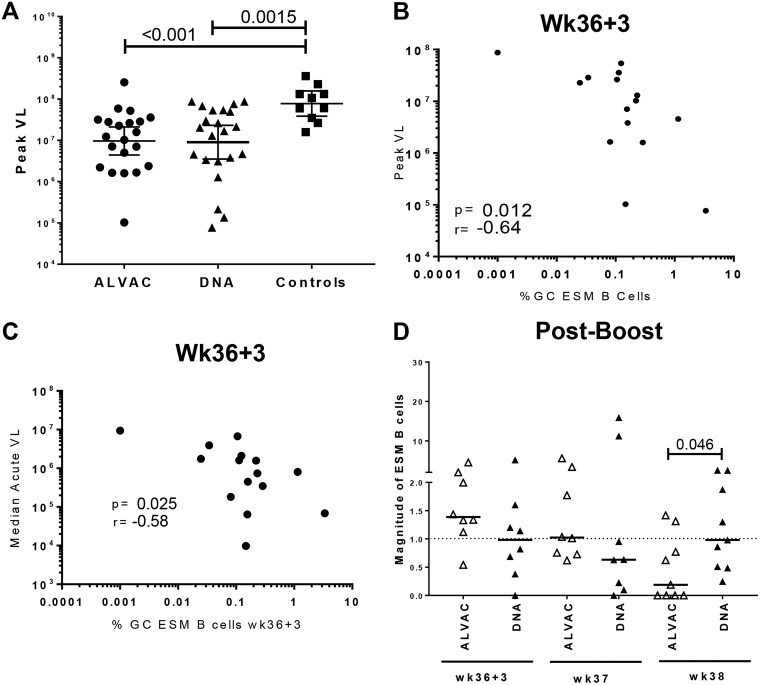

Postchallenge outcomes of GC B cell and TFH cell responses.

A secondary outcome of this study was modestly reduced viremia in the immunized macaques compared to the controls (T. Musich and M. Robert-Guroff, unpublished data). The peak levels of viremia for the ALVAC/Env and DNA&Env groups (geometric means of 9.69 × 106 and 9.02 × 106 SIV copies/ml, respectively) were reduced approximately 1 log compared to the controls (7.8 × 107 SIV copies/ml [Fig. 10A]). To evaluate the influence of vaccine-induced GC-derived Env-specific humoral responses on viremia control, we performed correlations of GC ESM B cells with peak viral loads of the immunized macaques. Although no association was observed when peak viremia was correlated with the frequency of GC ESM B cells at day 3 postprime, the frequency of GC ESM B cells at day 3 postboost inversely correlated with peak viral loads and overall acute-phase viremia (Fig. 10B and C), indicating that GC responses induced by the systemic boost had an impact on control of viral replication. While we observed a significantly elevated magnitude of GC ESM B cell responses in the small number of samples tested in the DNA&Env group compared to the ALVAC/Env group at week 38 (Fig. 10D), overall peak viral loads were not different between the two immunization groups (Fig. 10A). While this might suggest that viremia control in the DNA&Env group was more reliant than in the ALVAC/Env group on vaccine-induced Env antibody, evaluation of additional samples will be necessary to confirm this possibility.

FIG 10.

Immunological correlates of acute viremia control. (A) Peak viral loads (VL) in ALVAC/Env- and DNA&Env-immunized groups and controls post-SIV infection. Bars indicate geometric means with 95% confidence limits (CL). (B and C) Correlation analyses between GC ESM B cells at day 3 following the 2nd boost and peak viral loads (B) and (C) median peak viremia (weeks 1 to 8 postinfection). (D) Magnitudes of GC ESM B cell responses were compared between ALVAC/Env- and DNA&Env-immunized groups post-boost immunization. Bars represent median values.

DISCUSSION

TFH cells have been extensively characterized in humans and rhesus macaques during HIV/SIV infection (9, 11, 31, 46–49), and their role in supporting specific B cell responses during HIV/SIV infection has been well established (9, 13, 50–52). However, few studies have focused on TFH-B cell interactions following vaccination of rhesus macaques with SIV immunogens, a key model for preclinical HIV vaccine studies (53). We previously reported vaccine induction of SIV Env-specific TFH cells in draining LNs of rhesus macaques 2 weeks following immunization and the ability of this population to elicit SIV-specific systemic and mucosal humoral responses (13). In this study, we questioned whether earlier TFH-B cell interactions played a role in development of SIV-specific humoral immunity, as detailed kinetics of the GC reaction following macaque immunization have not been reported. In contrast to studies that assessed cellular and humoral responses 2 weeks or more following immunization (54–57), we included LN collections at day 3 following immunization, which provided data regarding peak TFH cell responses and GC maturation at an early stage, as well as at days 7 and 14. To avoid repeated LN biopsy specimens from each macaque, animals were organized into collection subgroups so immunological responses would not be compromised by excessive LN removals from the same animal. No macaque had more than 3 LN biopsy specimens over a 38-week period (Fig. 1). Inguinal LNs were obtained, as following mucosal administration to the upper respiratory tract the replicating Ad5hr-SIV vector exhibits broad biodistribution and persists in rectal macrophages for at least 25 weeks postimmunization (58). Lymphatic drainage from the rectum and anus include both inguinal and mesenteric LNs (59); however, invasive surgery would have been necessary to collect mesenteric LNs. Inguinal LNs were obtained following booster immunizations administered to the thigh. We biopsied whole LNs rather than using sequential sampling with the fine-needle aspiration technique, which has been applied in longitudinal assessments of LN cell subsets in HIV-1 patients and macaques (60–63). TFH cell evaluation using this method may be problematic, as the needle may withdraw cells from either the T or B cell zone of the LN (64). Moreover, the average cell yield per LN aspirate is ∼1 × 106 (61). In contrast, LN biopsy specimens provide reliable determination of TFH and B cell frequencies closest to in vivo conditions while providing sufficient cell numbers necessary for all the immunological assays in this study.

Previous studies demonstrated that mucosal immunization with replicating Ad-SIV recombinants induced potent mucosal SIV-specific antibody responses associated with delayed SIV acquisition and viremia control (14). Therefore, understanding the GC reaction after the Ad-SIV recombinant immunizations was of particular interest. Although significant increases in the frequency of GC TFH cells were not observed following Ad-SIV priming (Fig. 4A), observations of GC B cell subsets indicated a rapid initiation of a GC reaction. A marginally significant increase in GC B cells was observed 7 days following the second Ad-SIV recombinant immunization (Fig. 4C), together with significant increases in GC CCs (Fig. 5A) and ESM B cells (Fig. 5E) at the same time point. Moreover, significant correlations of GC TFH cells with GC B cells 3 and 14 days post-Ad immunization (Fig. 6B and C) and with CBs 14 days postimmunization (Fig. 8B) were seen, along with a significant correlation between CC frequencies and GC ESM B cells 14 days postimmunization (Fig. 8F), strengthening this conclusion.

An early GC reaction following the systemic booster immunizations was also seen. The abundance of GC TFH cells (Fig. 4A and B) and GC B cells (Fig. 4D) significantly increased 3 days after boosting, and subsequently the CC population increased significantly 7 and 14 days later (Fig. 5A). ESM B cells were significantly increased within 3 days of the systemic booster immunization (Fig. 5E). GC TFH cells were directly correlated with GC B cells 3 days post-systemic immunization (Fig. 6D), and by day 14, both GC TFH cells and CCs were correlated with ESM B cells (Fig. 8E and G). We have previously reported that boosting with SIV gp120 proteins following priming with replicating Ad5hr-SIV recombinants contributes to elevation of both cellular and humoral immune responses in rhesus macaques and to protection following SIVmac251 challenge (14, 65, 66). Our data here support the rapid initiation of the GC reaction following both the prime and boost phases of the vaccine regimen and its participation in generating SIV-specific humoral responses.

The GC is an environment of intense cellular communication in which TFH cells guide the maturation of B cells (67, 68). As TFH cells in LNs are a heterogeneous population consisting of distinct subsets (47), our study focused on analysis of TFH cells expressing the highest levels of PD-1, a subpopulation shown to be more functional and more prone to migrate toward the GC (69–71). Expression of the transcription factor BCL-6, needed for TFH cell responses within GCs (72, 73), promotes activation and upregulation of PD-1 in mice, and high levels of BCL-6 have been found exclusively in PD-1hi TFH cells in rhesus macaques (9, 74, 75). Thus, although PD-1 has been demonstrated to play a major role in inhibiting T cell responses (72), T cells located inside LN B cell follicles exhibit high PD-1 expression (73). Upregulation of PD-1 on TFH cells contributes to B cell survival in mature GCs and promotes GC maturation with increased IgG responses in rhesus macaques (71, 74, 75). In agreement with these reports, we observed that although non-GC TFH cells (CXCR5+ PD-1low/int) at 3 days following Ad-SIV recombinant immunization correlated significantly with GC B cells (Fig. 6E), a much stronger association was seen with GC TFH cells (CXCR5+ PD-1hi [Fig. 6B]), suggesting greater participation in provision of B cell help. GC TFH cells were strongly associated with CBs at day 14 following the mucosal prime (Fig. 8B), suggesting a role in GC B cell expansion. The significant association of the PD-1hi TFH cells induced 3 days after systemic immunization (Fig. 4A) with ESM B cells observed in bone marrow at week 38 (Fig. 9C) further suggests a role in GC maturation and generation of antibody responses.

The significant decrease of GC TFH cell levels at wk37 following the peak at week 36 + 3 (Fig. 4A) reflects downmodulation of PD-1. A mechanistic explanation might be intense engagement of PD-1 to its main ligand, PD-L1, highly expressed on the surface of GC B cells. Binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 on TFH cells compromises TFH cell proliferation, indicating that PD-L1+ GC B cells tightly regulate TFH expansion (76). A decrease of the GC TFH cell population at later time points postimmunization represents the expected kinetics of this population and might suggest intense TFH-B cell interaction prior to GC formation. In this study, however, the decrease of PD-1hi TFH cells did not hamper subsequent GC maturation, as confirmed by the presence of GC SIV ESM B cells in blood and bone marrow at week 38 (Fig. 9A and D), 14 days following the boost immunization.

Although we previously reported SIV Env-specific TFH activity based on IL-21 production in response to SIV Env peptide stimulation (13), in this study, we detected few IL-21+ GC TFH cells. Our previous study defined LN TFH cells as ICOS+ PD-1hi, whereas in this study, we examined a slightly different cell population: CXCR5+ PD-1hi cells. Whether this was responsible for the different results will require further investigation. However, detection of antigen-specific GC TFH cells has been difficult in other studies as well. Because cytokine release in GCs must be strictly controlled to provide survival signals exclusively to highly specific B cells, GC TFH cells naturally produce little cytokine and are difficult to detect by conventional intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) methods (33, 77, 78). Several studies have shown that the activated induced marker assay can more efficiently detect Ag-specific T cells compared to cytokine quantification (33, 79–81). However, the suitability of this technique for SIV-specific LN TFH cells was reported after we initiated our experiments (33) and the methodology could not be changed in the middle of the study.

Generation of antigen-specific memory B cells can either follow the GC pathway or take place outside the GC. In fact, unmutated memory B cells can be generated in early phases of the immune response, even prior to signals leading to GC initiation (42). We investigated humoral responses distinctly generated in GCs due to the higher antigen specificity attributed to GC B cells, a feature resulting from clonal selection controlled by GC TFH cells. IgG memory B cells generated via the GC pathway are long-lasting and have undergone greater rounds of SHM and affinity selection promoted by GC TFH cells (3, 82). Hence, memory B cells generated outside GCs and not dependent on TFH cell help exhibit lower antigenic affinity and provide less durable immunity (83). The immunological correlates presented in this study are consistent with efficient GC activity induced by GC TFH cells and subsequent GC-dependent generation of SIV ESM B cell responses, confirmed by the significant association between this late subset and CC abundance 2 weeks after both immunizations (Fig. 8F and G). Collectively, our results on GC TFH and GC B cells illustrate early GC formation and vaccine elicitation of both mucosal and systemic SIV-specific humoral immune responses.

In addition to GC cellular dynamics, we also investigated the association of early GC responses with postchallenge outcomes. The significant negative correlation observed between GC ESM B cells elicited at day 3 following the protein boost and acute-phase viremia control (Fig. 10B and C) emphasizes the pivotal role of the systemic boost immunization in the development of protective SIV humoral immunity. Other factors of course may impact viremia levels, such as virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and their interactions with other T cell subsets (41, 84, 85) and availability of virus-susceptible T helper cell subsets such as Th17 or CCR6 expressing CD4+ T cells (86–89). Nevertheless, the strong association between acute-phase viremia control and the early GC SIV ESM B cell response at day 3 postboost, a time point not previously associated with generation of antigen-specific responses within GCs, illustrates that following immunization, early TFH-dependent SIV specific memory B cell responses generated in GCs are important for control of viral replication.

Overall, our findings reinforce the importance of early induction of PD-1hi TFH cells (GC TFH) for GC maturation and induction of humoral immunity during vaccination. Early TFH-dependent GC activities and B cell maturation into SIV ESM cells led to sustained SIV Env-specific mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses in rectal mucosa and bone marrow and contributed to control of SIV postinfection. Knowledge of the contribution of TFH cells to development of long-lasting SIV-specific immunity is still limited and requires further elucidation. The GC reaction plays an indispensable role in enhancing the quality of SIV-specific antibodies, and consequently, more comprehensive studies are needed to better address how new vaccination strategies can induce more powerful TFH-dependent B cell responses leading to more efficient protection against SIV/HIV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All procedures, including immunization, sample collection, and viral challenge of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) and with standards outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the United States (90). All animals were housed at the AAALAC-accredited NCI Animal Facility, Bethesda, MD, under protocol no. VB012 approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee. Vaccine immunogens were administered to immobilized animals anesthetized by standard protocol, generally with 10 to 25 mg/kg of body weight of ketamine. Animals were also anesthetized for sample collections and viral challenges. All measures used to minimize animal distress were in accordance with the Guide and the recommendations of the Weatherall Report (91). Animals were housed in temperature-controlled facilities with an ambient temperature of 21 to 26°C, relative humidity of 30% to 70%, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Animals were provided with commercial primate diet and fresh fruit twice daily, and water was available at all times. Animals were also monitored for activity and overall health twice a day. Humane euthanasia endpoints were defined in case animals developed any condition that compromised their well-being and could not be alleviated by appropriate treatment. Euthanasia was performed with an overdose of pentobarbital (80 mg/kg), administered intravenously, and in accordance with recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association Panel on Euthanasia.

Animals, immunization, and challenge protocols.

Sixty naive rhesus macaques, negative for SIV, simian retrovirus (SRV), simian T cell leukemia virus (STLV), were enrolled in this preclinical vaccine study. The immune responses of 50 of the animals divided into 2 groups, the ALVAC/Env group (n = 25) and the DNA&Env group (n = 25), were evaluated to assess vaccine induction of humoral responses at mucosal and systemic sites. Preimmunization samples served as controls. Each immunization group contained 13 males and 12 females. Animals from both the ALVAC/Env and DNA&Env arms were primed with Ad5hr-SIVM766gp120-TM and Ad5hr-SIV239Gag at a dose of 5 × 108 PFU per recombinant per site intranasally plus orally at week 0 and intratracheally at week 12. Animals in ALVAC/Env group received 2 intramuscular immunizations at weeks 24 and 36 consisting of ALVAC-SIVM766Gag/Pro/gp120-TM at a concentration of 108 particles/dose in one thigh plus 200 μg each of gD-SIVM766 and gD-SIVCG7V gp120 proteins administered in alum hydroxide as adjuvant in the other thigh. Animals in the DNA&Env group were immunized at weeks 24 and 36 with DNA encoding SIVM766 gp120-TM (1 mg; plasmid 267S) plus SIV239 gag/prt (1 mg; plasmid 274S) plus rhesus macaque IL-12 DNA (0.2 mg) administered intramuscularly to the left and right inner thighs, followed by electroporation (Elgen 1000; Inovio Pharmaceuticals Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA). Immediately following, the same gD-gp120 proteins formulated in alum phosphate were administered to the same sites. Ten control macaques received empty Ad5hr vector (a total dose equivalent to the Ad dose administered to the immunized macaques) and alum only. At week 42, the macaques were challenged intrarectally with up to 15 weekly low doses of SIVmac251 for those macaques that remained uninfected. Infection was determined by viral loads of ≥50 SIV RNA copies/ml plasma assessed weekly. Plasma viral loads were assessed by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) (92).

Tissue collection and sample processing.

Inguinal LN biopsy specimens were obtained from all macaques at 4 weeks preimmunization and from macaque subgroups at 3, 7, and 14 days following the second Ad5hr mucosal prime (week 12 + 3, week 13, and week 14) and 3, 7 and 14 days following the second ALVAC/Env or DNA&Env intramuscular boost (week 36 + 3, week 37, and week 38) (Fig. 1). Both day 3 subgroups consisted of 8 macaques each from the ALVAC/Env and DNA&Env groups and 4 controls, day 7 subgroups consisted of the same number of different macaques from the same groups, and day 14 subgroups consisted of 9 different macaques from each of the ALVAC/Env and DNA&Env groups and 2 controls. Blood, bone marrow, and rectal pinch biopsy specimens were obtained from all macaques 4 weeks prior to vaccination, 14 days following the second mucosal prime, and 14 days following the second intramuscular boost. Lymphocytes were isolated from LN biopsy specimens as previously described (93) and stored frozen in fetal bovine serum (FBS)–10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution. Blood and bone marrow lymphocytes were isolated by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll, treated with ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) buffer for red blood cell lysis, and stored frozen in FBS–10% DMSO as previously described (49). Rectal biopsy specimens were processed as previously described (94) and assayed immediately. Briefly, the biopsy specimens were rinsed and minced using a scalpel and 19-gauge needle in prewarmed digestive medium consisting of RPMI 1640, 1× antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 2 mM l-glutamine (all from Invitrogen), and 2 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich). The minced material was transferred to 50-ml conical tubes and incubated in digestive medium at 37°C for 30 min, with pulse vortexing every 5 min. After incubation, the mucosal tissues were transferred into 6-well plates and passed 5 or 6 times through a blunt-end cannula attached to a 12-ml syringe for liberation of cells. The cell suspension was then passed through a 70-μm cell strainer and washed with 30 ml of R10 medium (RPMI 1640, 1× antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10% FBS). The freshly isolated cells were distributed among fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) tubes and stained for flow cytometry for evaluation of rectal SIVgp120-specific memory B cells as described elsewhere (49, 94).

Staining of TFH and TFR cells for flow cytometry.

Viably frozen LN cells were thawed, washed with R10, and separated into four groups of 1.5 × 106 cells each for no exogenous stimulation, antigen stimulation with 1 μg/ml of SIVM766 or SIVCG7V gp120 peptide pools consisting of complete sets of 15-mer peptides overlapping by 11 amino acids (aa) (Advanced Bioscience Laboratories Inc., Rockville, MD), or 1× phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-ionomycin cell stimulation cocktail (eBiosciences). Prior to incubation for 6 h at 37°C, the cells received a mixture of 2 μg/ml of anti-CD49-d and anti-CD28 (BD Biosciences), BD GolgiPlug and BD GolgiStop, as well as allophycocyanin (APC)-eFluor780 anti-CD197 (anti-CCR7) clone 2D12 (eBiosciences) at a concentration recommended by the manufacturer. Following incubation, the cells were washed with FACS buffer (Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline [DPBS], 2% FBS) and stained for surface markers: BV605 anti-PD-1 (EH12.2H7) and BV785 anti-CD25 (BC96) (Biolegend); peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-eFluor710 anti-CXCR5 (MU5UBEE) (eBiosciences), phycoerythrin (PE)-CF594 anti-CD95 (DX2), Alexa Fluor anti-CD3 (SP34-2), and BV711 anti-CD4 (L200) (BD Biosciences). The aqua LIVE/DEAD viability dye (Invitrogen) was added during surface staining for dead cell exclusion. Subsequently, cells were washed with FACS buffer, permeabilized with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm for intracellular cytokine staining (TFH cells) or eBioscience Foxp3 fixation/permeabilization buffer (TFR cells) for 15 min at room temperature, and intracellularly stained with PE anti-IL-21 (3A3-N2.1), Alexa Fluor 647 anti-Ki67 (B56), and PE-Cy5 anti-CD154 (TRAP1) (BD Biosciences) and eFluor660 anti-Foxp3 (236A/E7) (eBioscience). After a final wash with BD permeabilization/wash buffer (1×; TFH cells) or eBioscience Foxp3 permeabilization buffer (1×; TFR cells), 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was added and cells were maintained at 4°C until acquisition. At least 300,000 events were acquired using an 18-laser LSRII (BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed with FlowJo 10.2 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR), and gates were defined using isotype and fluorescence-minus-one controls.

B cell staining for flow cytometry.

Viably frozen cells obtained from inguinal LNs were thawed, washed in complete R10 medium, and stained for flow cytometry as previously described together with freshly obtained cells from the rectal biopsy specimens (13, 94, 95). Briefly, surface staining was carried out at room temperature using eFL-650NC anti-CD20 (2H7), PE-Cy5 anti-CD27 (O323) and PE-Cy7 anti-CD95 (DX2) (eBiosciences), Texas Red anti-IgD polyclonal antibody (Southern Biotech), and PE-Cy5 anti-CD19 (J3-119) (Beckman Coulter). The aqua LIVE/DEAD viability dye (Invitrogen) was added during surface staining for dead cell exclusion. Unconjugated anti-CD4 antibody clones OKT4 and 19Thy5D7 (NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource) were added to block reactivity to CD4. Cells were washed in FACS buffer after 25 min of incubation. Envelope protein staining was carried out by adding biotinylated gp120 proteins (2 μg/sample), and cells were incubated for 25 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed with FACS buffer and incubated for 25 min at 4°C with streptavidin conjugated to allophycocyanin and again washed with FACS buffer. After envelope protein staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using a transcription factor buffer set (BD Biosciences) for 15 min according to manufacturer specifications. Following permeabilization, cells were stained intracellularly with APC-Cy7 anti-BCL6 (K112-91) and Alexa Fluor 700 anti-Ki67 (B56) (BD Biosciences) at room temperature for 25 min. After a final wash with FACS buffer, 2% PFA was added and cells were maintained at 4°C until acquisition using an 18-laser LSRII (BD Biosciences). Approximately 500,000 events were acquired and were analyzed with FlowJo 10.2 as previously described.

SIV-specific antibody-secreting cells in bone marrow.

Both total IgG and IgA and SIVM766 and SIVCG7V gp120-specific IgG and IgA antibody-secreting cells (ASC) were quantified in bone marrow by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay as previously described (96). Briefly, bone marrow cells were thawed and polyclonally stimulated for 3 days (day 3) in the presence of 1 μg/ml of CpG ODN-2006 (MGW Operon, Huntsville, AL), 50 ng/ml of IL-21 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 0.5 μg/ml of anti-human sCD40L (Peprotech) for assessment of memory B cells. Env-specific IgA and IgG ASC, with or without stimulation, were standardized to the total number of IgG and IgA ASC and reported as percent IgA and IgG Env-specific activity relative to the number of total IgG and IgA ASC.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software), and P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Paired data were assessed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, whereas unpaired data were assessed by the Mann-Whitney U test. The Spearman rank correlation test was used to assess immunological correlates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the veterinarians, Joshua Kramer and Matthew Breed, and the animal caretaker staff, including William Magnanelli and Michelle Metrinko, at the NCI Animal Facility for conducting all animal procedures and for their expert care of the macaques, Katherine McKinnon and Sophia Brown (Vaccine Branch Flow Core, NCI) for expert advice on flow cytometry and technical support, Irene Kalisz and Hye-Kyung Chung (Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Inc.) for serologic and virological analyses, and Nancy Miller (DAIDS, NIAID) for provision of the SIVmac251 challenge stock, originally obtained from Ronald Desrosiers. The following reagents were obtained from the NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource: anti-CD4 OKT4 and anti-CD4 T4/19Thy5D7.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ma CS, Deenick EK, Batten M, Tangye SG. 2012. The origins, function, and regulation of T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med 209:1241–1253. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crotty S. 2014. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity 41:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. 2009. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity 30:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. 2011. Germinal center B and follicular helper T cells: siblings, cousins or just good friends? Nat Immunol 12:472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linterman MA, Beaton L, Yu D, Ramiscal RR, Srivastava M, Hogan JJ, Verma NK, Smyth MJ, Rigby RJ, Vinuesa CG. 2010. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med 207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Silva NS, Klein U. 2015. Dynamics of B cells in germinal centres. Nat Rev Immunol 15:137–148. doi: 10.1038/nri3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton DR, Poignard P, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. 2012. Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science 337:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1225416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotty S. 2011. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol 29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, Gerner MY, Boswell KL, Wloka K, Smith EC, Ambrozak DR, Sandler NG, Timmer KJ, Sun X, Pan L, Poholek A, Rao SS, Brenchley JM, Alam SM, Tomaras GD, Roederer M, Douek DC, Seder RA, Germain RN, Haddad EK, Koup RA. 2012. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J Clin Invest 122:3281–3294. doi: 10.1172/JCI63039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto T, Lynch RM, Gautam R, Matus-Nicodemos R, Schmidt SD, Boswell KL, Darko S, Wong P, Sheng Z, Petrovas C, McDermott AB, Seder RA, Keele BF, Shapiro L, Douek DC, Nishimura Y, Mascola JR, Martin MA, Koup RA. 2015. Quality and quantity of TFH cells are critical for broad antibody development in SHIVAD8 infection. Sci Transl Med 7:298ra120. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cubas RA, Mudd JC, Savoye AL, Perreau M, van Grevenynghe J, Metcalf T, Connick E, Meditz A, Freeman GJ, Abesada-Terk G Jr, Jacobson JM, Brooks AD, Crotty S, Estes JD, Pantaleo G, Lederman MM, Haddad EK. 2013. Inadequate T follicular cell help impairs B cell immunity during HIV infection. Nat Med 19:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nm.3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Tuero I, Mohanram V, Musich T, Pegu P, Valentin A, Sui Y, Rosati M, Bear J, Venzon DJ, Kulkarni V, Alicea C, Pilkington GR, Liyanage NP, Demberg T, Gordon SN, Wang Y, Hogg AE, Frey B, Patterson LJ, DiPasquale J, Montefiori DC, Sardesai NY, Reed SG, Berzofsky JA, Franchini G, Felber BK, Pavlakis GN, Robert-Guroff M. 2014. Humoral immunity induced by mucosal and/or systemic SIV-specific vaccine platforms suggests novel combinatorial approaches for enhancing responses. Clin Immunol 153:308–322. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Demers A, Shaw JM, Kang G, Ball D, Tuero I, Musich T, Mohanram V, Demberg T, Karpova TS, Li Q, Robert-Guroff M. 2016. Vaccine induction of lymph node-resident simian immunodeficiency virus Env-specific T follicular helper cells in rhesus macaques. J Immunol 196:1700–1710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao P, Patterson LJ, Kuate S, Brocca-Cofano E, Thomas MA, Venzon D, Zhao J, DiPasquale J, Fenizia C, Lee EM, Kalisz I, Kalyanaraman VS, Pal R, Montefiori D, Keele BF, Robert-Guroff M. 2012. Replicating adenovirus-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) recombinant priming and envelope protein boosting elicits localized, mucosal IgA immunity in rhesus macaques correlated with delayed acquisition following a repeated low-dose rectal SIV(mac251) challenge. J Virol 86:4644–4657. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06812-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, Premsri N, Namwat C, de Souza M, Adams E, Benenson M, Gurunathan S, Tartaglia J, McNeil JG, Francis DP, Stablein D, Birx DL, Chunsuttiwat S, Khamboonruang C, Thongcharoen P, Robb ML, Michael NL, Kunasol P, Kim JH. 2009. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med 361:2209–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pegu P, Vaccari M, Gordon S, Keele BF, Doster M, Guan Y, Ferrari G, Pal R, Ferrari MG, Whitney S, Hudacik L, Billings E, Rao M, Montefiori D, Tomaras G, Alam SM, Fenizia C, Lifson JD, Stablein D, Tartaglia J, Michael N, Kim J, Venzon D, Franchini G. 2013. Antibodies with high avidity to the gp120 envelope protein in protection from simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(mac251) acquisition in an immunization regimen that mimics the RV-144 Thai trial. J Virol 87:1708–1719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02544-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaccari M, Gordon SN, Fourati S, Schifanella L, Liyanage NPM, Cameron M, Keele BF, Shen X, Tomaras GD, Billings E, Rao M, Chung AW, Dowell KG, Bailey-Kellogg C, Brown EP, Ackerman ME, Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Whitney S, Doster MN, Binello N, Pegu P, Montefiori DC, Foulds K, Quinn DS, Donaldson M, Liang F, Loré K, Roederer M, Koup RA, McDermott A, Ma Z-M, Miller CJ, Phan TB, Forthal DN, Blackburn M, Caccuri F, Bissa M, Ferrari G, Kalyanaraman V, Ferrari MG, Thompson D, Robert-Guroff M, Ratto-Kim S, Kim JH, Michael NL, Phogat S, Barnett SW, Tartaglia J, Venzon D, Stablein DM, Alter G, Sekaly R-P, Franchini G. 2016. Adjuvant-dependent innate and adaptive immune signatures of risk of SIVmac251 acquisition. Nat Med 22:762–770. doi: 10.1038/nm.4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz BT, Teigler JE, Pissani F, Oster AF, Kranias G, Alter G, Marovich M, Eller MA, Dittmer U, Robb ML, Kim JH, Michael NL, Bolton D, Streeck H. 2016. Circulating HIV-specific interleukin-21(+)CD4(+) T cells represent peripheral Tfh cells with antigen-dependent helper functions. Immunity 44:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jalah R, Kulkarni V, Patel V, Rosati M, Alicea C, Bear J, Yu L, Guan Y, Shen X, Tomaras GD, LaBranche C, Montefiori DC, Prattipati R, Pinter A, Bess J Jr, Lifson JD, Reed SG, Sardesai NY, Venzon DJ, Valentin A, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK. 2014. DNA and protein co-immunization improves the magnitude and longevity of humoral immune responses in macaques. PLoS One 9:e91550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaccari M, Franchini G. 2018. T cell subsets in the germinal center: lessons from the macaque model. Front Immunol 9:348. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ansel KM, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Ngo VN, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Cyster JG. 1999. In vivo-activated CD4 T cells upregulate CXC chemokine receptor 5 and reprogram their response to lymphoid chemokines. J Exp Med 190:1123–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes NM, Allen CD, Lesley R, Ansel KM, Killeen N, Cyster JG. 2007. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1 high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J Immunol 179:5099–5108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohler SL, Pham MN, Folkvord JM, Arends T, Miller SM, Miles B, Meditz AL, McCarter M, Levy DN, Connick E. 2016. Germinal center T follicular helper cells are highly permissive to HIV-1 and alter their phenotype during virus replication. J Immunol 196:2711–2722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Ettinger R, Kim H-P, Wang G, Qi C-F, Hwu P, Shaffer DJ, Akilesh S, Roopenian DC, Morse HC, Lipsky PE, Leonard WJ. 2004. Regulation of B cell differentiation and plasma cell generation by IL-21, a novel inducer of Blimp-1 and Bcl-6. J Immunol 173:5361–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park HJ, Kim DH, Lim SH, Kim WJ, Youn J, Choi YS, Choi JM. 2014. Insights into the role of follicular helper T cells in autoimmunity. Immune Netw 14:21–29. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinuesa CG, Linterman MA, Yu D, MacLennan IC. 2016. Follicular helper T cells. Annu Rev Immunol 34:335–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. 2009. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol 10:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein U, Tu Y, Stolovitzky GA, Keller JL, Haddad J Jr, Miljkovic V, Cattoretti G, Califano A, Dalla-Favera R. 2003. Transcriptional analysis of the B cell germinal center reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:2639–2644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437996100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agematsu K, Nagumo H, Yang FC, Nakazawa T, Fukushima K, Ito S, Sugita K, Mori T, Kobata T, Morimoto C, Komiyama A. 1997. B cell subpopulations separated by CD27 and crucial collaboration of CD27+ B cells and helper T cells in immunoglobulin production. Eur J Immunol 27:2073–2079. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demberg T, Brocca-Cofano E, Xiao P, Venzon D, Vargas-Inchaustegui D, Lee EM, Kalisz I, Kalyanaraman VS, Dipasquale J, McKinnon K, Robert-Guroff M. 2012. Dynamics of memory B-cell populations in blood, lymph nodes, and bone marrow during antiretroviral therapy and envelope boosting in simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques. J Virol 86:12591–12604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00298-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crotty S. 2015. A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 15:185–189. doi: 10.1038/nri3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perreau M, Savoye AL, De Crignis E, Corpataux JM, Cubas R, Haddad EK, De Leval L, Graziosi C, Pantaleo G. 2013. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J Exp Med 210:143–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Havenar-Daughton C, Reiss SM, Carnathan DG, Wu JE, Kendric K, Torrents de la Pena A, Kasturi SP, Dan JM, Bothwell M, Sanders RW, Pulendran B, Silvestri G, Crotty S. 2016. Cytokine-independent detection of antigen-specific germinal center T follicular helper cells in immunized nonhuman primates using a live cell activation-induced marker technique. J Immunol 197:994–1002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerfoot SM, Yaari G, Patel JR, Johnson KL, Gonzalez DG, Kleinstein SH, Haberman AM. 2011. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity 34:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bannard O, Horton RM, Allen CD, An J, Nagasawa T, Cyster JG. 2013. Germinal center centroblasts transition to a centrocyte phenotype according to a timed program and depend on the dark zone for effective selection. Immunity 39:912–924. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Hart M, Chui C, Ajuogu A, Brian IJ, de Cassan SC, Borrow P, Draper SJ, Douglas AD. 2016. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell responses to viral vector and protein-in-adjuvant vaccines. J Immunol 197:1242–1251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fields ML, Hondowicz BD, Metzgar MH, Nish SA, Wharton GN, Picca CC, Caton AJ, Erikson J. 2005. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells inhibit the maturation but not the initiation of an autoantibody response. J Immunol 175:4255–4264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, Srivastava M, Divekar DP, Beaton L, Hogan JJ, Fagarasan S, Liston A, Smith KG, Vinuesa CG. 2011. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med 17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sage PT, Ron-Harel N, Juneja VR, Sen DR, Maleri S, Sungnak W, Kuchroo VK, Haining WN, Chevrier N, Haigis M, Sharpe AH. 2016. Suppression by TFR cells leads to durable and selective inhibition of B cell effector function. Nat Immunol 17:1436–1446. doi: 10.1038/ni.3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miles B, Miller SM, Connick E. 2016. CD4 T follicular helper and regulatory cell dynamics and function in HIV infection. Front Immunol 7:659. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahman MA, McKinnon KM, Karpova TS, Ball DA, Venzon DJ, Fan W, Kang G, Li Q, Robert-Guroff M. 2018. Associations of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific follicular CD8(+) T cells with other follicular T cells suggest complex contributions to SIV viremia control. J Immunol 200:2714–2726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takemori T, Kaji T, Takahashi Y, Shimoda M, Rajewsky K. 2014. Generation of memory B cells inside and outside germinal centers. Eur J Immunol 44:1258–1264. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oropallo MA, Cerutti A. 2014. Germinal center reaction: antigen affinity and presentation explain it all. Trends Immunol 35:287–289. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacLennan IC. 1994. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol 12:117–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corcoran LM, Tarlinton DM. 2016. Regulation of germinal center responses, memory B cells and plasma cell formation—an update. Curr Opin Immunol 39:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moukambi F, Rabezanahary H, Rodrigues V, Racine G, Robitaille L, Krust B, Andreani G, Soundaramourty C, Silvestre R, Laforge M, Estaquier J. 2015. Early loss of splenic Tfh cells in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Velu V, Mylvaganam GH, Gangadhara S, Hong JJ, Iyer SS, Gumber S, Ibegbu CC, Villinger F, Amara RR. 2016. Induction of Th1-biased T follicular helper (Tfh) cells in lymphoid tissues during chronic simian immunodeficiency virus infection defines functionally distinct germinal center Tfh cells. J Immunol 197:1832–1842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrovas C, Koup RA. 2014. T follicular helper cells and HIV/SIV-specific antibody responses. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 9:235–241. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohanram V, Demberg T, Musich T, Tuero I, Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Miller-Novak L, Venzon D, Robert-Guroff M. 2016. B cell responses associated with vaccine-induced delayed SIVmac251 acquisition in female rhesus macaques. J Immunol 197:2316–2324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Onabajo OO, Mattapallil JJ. 2013. Expansion or depletion of T follicular helper cells during HIV infection: consequences for B cell responses. Curr HIV Res 11:595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pissani F, Streeck H. 2014. Emerging concepts on T follicular helper cell dynamics in HIV infection. Trends Immunol 35:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blackburn MJ, Zhong-Min M, Caccuri F, McKinnon K, Schifanella L, Guan Y, Gorini G, Venzon D, Fenizia C, Binello N, Gordon SN, Miller CJ, Franchini G, Vaccari M. 2015. Regulatory and helper follicular T cells and antibody avidity to simian immunodeficiency virus glycoprotein 120. J Immunol 195:3227–3236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans DT, Silvestri G. 2013. Nonhuman primate models in AIDS research. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 8:255–261. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328361cee8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosati M, Valentin A, Jalah R, Patel V, von Gegerfelt A, Bergamaschi C, Alicea C, Weiss D, Treece J, Pal R, Markham PD, Marques ET, August JT, Khan A, Draghia-Akli R, Felber BK, Pavlakis GN. 2008. Increased immune responses in rhesus macaques by DNA vaccination combined with electroporation. Vaccine 26:5223–5229. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iyer SS, Gangadhara S, Victor B, Gomez R, Basu R, Hong JJ, Labranche C, Montefiori DC, Villinger F, Moss B, Amara RR. 2015. Codelivery of envelope protein in alum with MVA vaccine induces CXCR3-biased CXCR5+ and CXCR5- CD4 T cell responses in rhesus macaques. J Immunol 195:994–1005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]