Alphaviruses include important human pathogens such as Chikungunya and the encephalitic alphaviruses. There are currently no licensed alphavirus vaccines or effective antiviral therapies, and more molecular information on virus particle structure and function is needed. Here, we highlight the important role of the E2 juxtamembrane D-loop in mediating virus budding and particle production. Our results demonstrated that this E2 region affects both the formation of the external glycoprotein lattice and its interactions with the internal capsid protein shell.

KEYWORDS: alphavirus, virus assembly, virus budding

ABSTRACT

Alphaviruses are small enveloped RNA viruses that bud from the host cell plasma membrane. Alphavirus particles have a highly organized structure, with a nucleocapsid core containing the RNA genome surrounded by the capsid protein, and a viral envelope containing 80 spikes, each a trimer of heterodimers of the E1 and E2 glycoproteins. The capsid protein and envelope proteins are both arranged in organized lattices that are linked via the interaction of the E2 cytoplasmic tail/endodomain with the capsid protein. We previously characterized the role of two highly conserved histidine residues, H348 and H352, located in an external, juxtamembrane region of the E2 protein termed the D-loop. Alanine substitutions of H348 and H352 inhibit virus growth by impairing late steps in the assembly/budding of virus particles at the plasma membrane. To investigate this budding defect, we selected for revertants of the E2-H348/352A double mutant. We identified eleven second-site revertants with improved virus growth and mutations in the capsid, E2 and E1 proteins. Multiple isolates contained the mutation E2-T402K in the E2 endodomain or E1-T317I in the E1 ectodomain. Both of these mutations were shown to partially restore H348/352A growth and virus assembly/budding, while neither rescued the decreased thermostability of H348/352A. Within the alphavirus particle, these mutations are positioned to affect the E2-capsid interaction or the E1-mediated intertrimer interactions at the 5-fold axis of symmetry. Together, our results support a model in which the E2 D-loop promotes the formation of the glycoprotein lattice and its interactions with the internal capsid protein lattice.

IMPORTANCE Alphaviruses include important human pathogens such as Chikungunya and the encephalitic alphaviruses. There are currently no licensed alphavirus vaccines or effective antiviral therapies, and more molecular information on virus particle structure and function is needed. Here, we highlight the important role of the E2 juxtamembrane D-loop in mediating virus budding and particle production. Our results demonstrated that this E2 region affects both the formation of the external glycoprotein lattice and its interactions with the internal capsid protein shell.

INTRODUCTION

Alphaviruses include important and emerging human pathogens such as Chikungunya (CHIKV) and Mayaro virus and the encephalitic alphaviruses such as Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) (reviewed in references 1and 2). Alphaviruses are enveloped plus-sense RNA viruses that have highly organized structures (1, 3). The internal core contains the genomic RNA surrounded by a T=4 icosahedral lattice composed of 240 copies of the capsid protein. This nucleocapsid is enveloped by a viral membrane derived from the host cell plasma membrane during budding. The envelope contains a T=4 lattice of 240 copies of the E1 and E2 transmembrane glycoproteins organized into 80 spikes that are trimers of E1/E2 heterodimers (1, 3).

Budding of the virus particle requires a specific 1:1 interaction between the E2 envelope protein and the capsid protein (reviewed in reference 4). This has been extensively characterized for alphaviruses such as Sindbis virus and Semliki Forest virus (SFV). The interaction is mediated by the E2 C-terminal cytoplasmic tail/endodomain, which contains a highly conserved Tyr-X-Leu motif that interacts with a hydrophobic pocket on the capsid protein (5–8). For example, substitution of the critical tyrosine Y399 in SFV with a charged residue allows transport of the envelope proteins to the plasma membrane and formation of cytoplasmic nucleocapsids but impairs E2-nucleocapsid interaction and inhibits budding (7). Within the hydrophobic pocket, capsid residues Y184 and W251 interact with E2-Y399 to form an energetically favorable aromatic network, which may help provide the energy necessary for membrane curvature and virus budding (reviewed in reference 8). The E1/E2 heterodimer interaction also plays an important role in budding, and mutations that perturb dimer formation or stability can inhibit budding (see, for example, reference 9). In contrast, the viral genome is not required for particle production, since virus-like particles can be efficiently produced by expression of the alphavirus structural proteins alone (10).

While some of the viral protein requirements for budding have thus been identified, many questions remain on how particle assembly and budding occur. Both the capsid protein and the envelope proteins form organized lattices, but the relative importance of the nucleocapsid lattice versus the envelope protein lattice in promoting particle assembly and budding is unclear (reviewed in reference 4). Nucleocapsids assemble in the cytoplasm of infected cells in the absence of envelope protein expression (10, 11), and purified capsid protein can also assemble into nucleocapsid-like structures when incubated with RNA in vitro (12–15). However, interaction of intracellular nucleocapsids with the envelope proteins is clearly required for virus particle production, as discussed above. Capsid protein mutants that are deficient in capsid-capsid interactions do not form cytoplasmic nucleocapsids but are still able to form nucleocapsids at the plasma membrane and bud into virus particles, indicating that the glycoprotein lattice itself can promote nucleocapsid formation (5, 16–18). The evidence also suggests that cytoplasmic nucleocapsids undergo rearrangements during budding (5, 11, 19), suggesting that the mature particle structure may be influenced by interactions between the two lattices. While residues important in formation of the capsid protein lattice have been identified (reviewed in reference 20), less is known about the role of specific residues in mediating interactions within the envelope protein lattice.

Our previous studies showed that alanine substitution of two conserved histidine residues, E2-H348 and -H352, in the juxtamembrane D-loop region of E2 produces a >1.6-log reduction in the growth of SFV (21). Single H/A substitutions cause comparable decreases in SFV growth. The E2-H348/352A mutations do not affect E2/E1 protein biosynthesis, transport to the plasma membrane, maturation, or heterodimer stability. The capsid protein/nucleocapsid still becomes localized at the plasma membrane, but virus budding is reduced. In addition, the mutant virus particles have significantly reduced thermostability at 50°C compared to wild-type (WT) virus, although both mutant particle morphology and specific infectivity appear normal. Analysis in the context of the atomic models of the glycoprotein shells of CHIKV and VEEV indicates that in the heterodimer E2-H348 and -H352 make specific contacts with conserved residues in the stem region of E1 (21). We hypothesized that contacts between the E2 D-loop and the E1 stem are important in establishing the glycoprotein lattice necessary for virus budding. However, we had no direct evidence for effects on the glycoprotein lattice.

Revertants can be a powerful tool to identify additional sites and residues involved in a mutant phenotype and to more fully characterize the mechanism of the original mutation. Here, we selected for revertants that restore the growth defect of the E2-H348/352A mutant. We identified and characterized second site rescue mutations in both E2 and E1. The locations of these mutations support a role for the D-loop in promoting formation of the envelope protein lattice. They also emphasize the interrelationship of the internal nucleocapsid architecture and the external envelope protein lattice.

(This research was conducted by Emily A. Byrd in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. from the Graduate Division of Medical Sciences of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, 2017.)

RESULTS

Selection of H348/352A revertants.

Our previous results showed that the growth of the E2-H348/352A mutant is significantly impaired due to a defect at a late stage of virus budding at the plasma membrane (21). We also noted that the mutant plaque size was reduced (data not shown). To obtain further insights into the impaired particle assembly, we selected for revertants of H348/352A by serial passaging and screening for increased plaque size. BHK cells were electroporated with H348/352A RNA, plated in independent culture dishes, and cultured at 37°C until a cytopathic effect was observed, and titers were determined by a plaque assay. Larger plaque sizes predominated by passage 7, at which point viruses were plaque purified and expanded, and the sequences of their structural proteins were determined.

Eleven independently isolated revertants were identified in the selection. Sequence analysis revealed that these viruses were all second-site revertants that retained the original H348/352A mutations but had acquired 1 to 2 amino acid changes in the capsid, E2, and/or E1 proteins (Table 1). Each mutation was the result of a single nucleotide substitution (data not shown), while true reversion from alanine back to histidine would require two nucleotide changes. Many of the mutations occurred in residues known to be involved in E2-E1 contacts or E1-E1 interspike contacts (Table 1) (22). Two of the mutations, E2-T402K and E1-T317I, were independently isolated three times, with the E1-T317I mutation always accompanied by an additional mutation in either E1 or the capsid protein.

TABLE 1.

Second-site revertants of the SFV H348/352A mutant

| Mutationa | Location | Contacts |

|---|---|---|

| E2-T402K | Cytoplasmic tail | Near capsid interacting region |

| E2-T402K | Cytoplasmic tail | Near capsid interacting region |

| E2-T402K | Cytoplasmic tail | Near capsid interacting region |

| E1-A272S | Domain I | E2-E1 contacts |

| E1-T317I | Domain III | E1-E1 interspike contacts |

| C-D180N | ||

| E1-T317I | Domain III | E1-E1 interspike contacts |

| C-T8P | ||

| E1-T317I | Domain III | E1-E1 interspike contacts |

| E1-T5A | Domain I | |

| E1-V148A | Domain I | |

| E1-I162L | Domain I | |

| E1-N175Y | Domain II | E1-E1 interspike contacts |

| E1-E381V | E1 stem | E1-E1 interspike contacts |

| C-Q172K | ||

| E1-P400S | E1 stem |

Boldface text indicates mutations that appeared multiple times in independently selected viruses.

Note that while these isolates are all second-site revertants, we refer to them here simply as “revertants.”

Growth of revertant viruses.

To determine whether the revertants showed recovery of the impaired growth phenotype of the H348/352A mutant, BHK cells were infected with WT, H348/352A, and revertant viruses at a multiplicity of 1 PFU/cell. Cell media were collected at the indicated time points, and titers were determined by plaque assay. Since the E2-T402K and E1-T317I mutations appeared three times, only one of each of these isolates was assayed: E2-T402K and E1-T317I C-D180N.

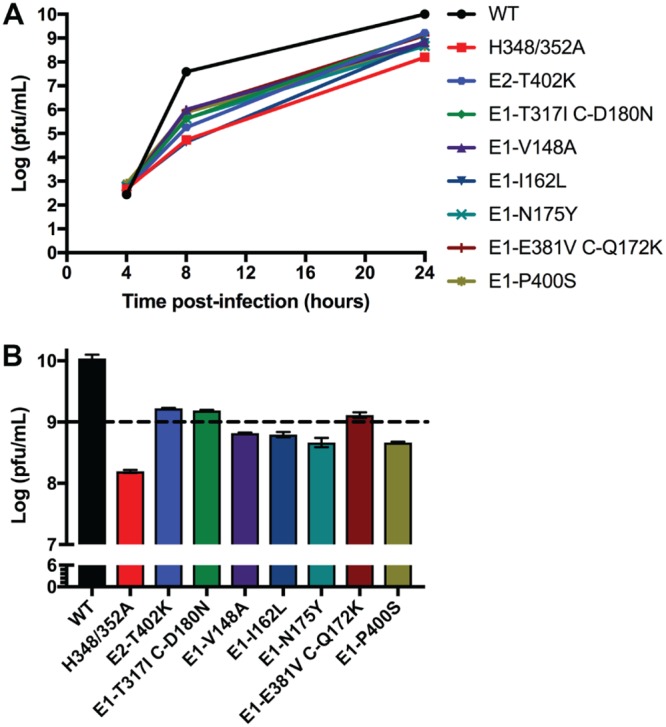

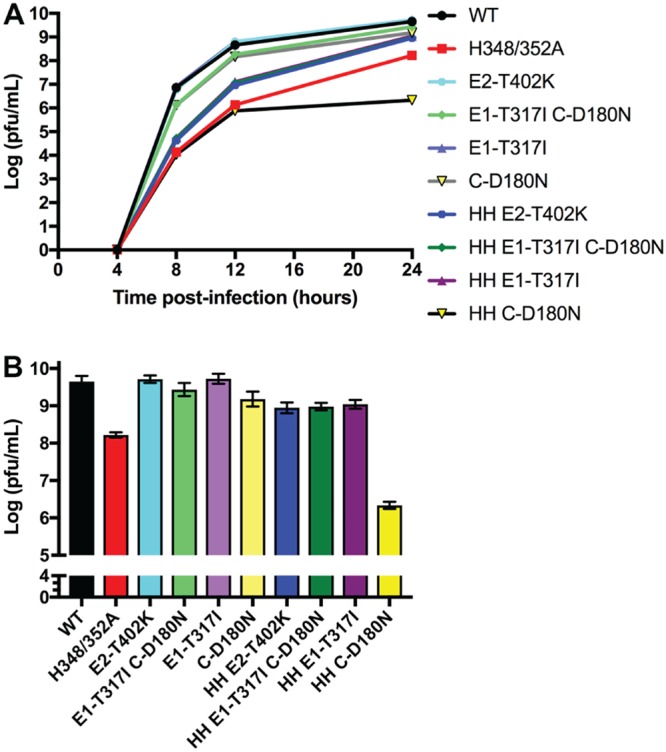

In agreement with our previous results, H348/352A virus production at 24 h postinfection (hpi) was decreased by ∼1.8 logs compared to that of WT SFV (Fig. 1A and B). All of the revertants showed improved growth compared to H348/352A, with titers at 24 hpi increased by ∼0.5 logs (E1-I162L, E1-N175Y, E1-V148A, and E1-P400S) or ∼1 log (E2-T402K, E1-T317I C-D180N, and E1-E381V C-Q172K). The latter three revertants had titers of >109 PFU/ml at 24 hpi or <1 log lower than the WT titer (Fig. 1B). Based on their representation and strong phenotypes, we chose the E2-T402K and E1-T317I C-D180N revertants for further study.

FIG 1.

Revertant virus growth. Plaque-purified virus stocks from the revertant selection were used to infect BHK cells at a multiplicity of 1 PFU/cell (see also Table 1). The cells were then incubated at 37°C, the media harvested at the indicated times, and virus was quantitated by plaque assay. (A) Growth curves shown are the average of two independent experiments. (B) Comparison of WT and revertant virus growth at 24 hpi (data from panel A). The dotted line indicates a threshold set at 109 PFU/ml, 1 log lower than the growth of the WT virus. Data shown are the average of two experiments, with the range indicated by the bars.

Characterization of E2-T402K, E1-T317I, and C-D180N.

To characterize each revertant, the identified mutations were cloned de novo into both the WT and H348/352A backgrounds using the WT or H348/352A mutant infectious clones. The following clones were constructed, with HH indicating the H348/352A background: E2-T402K, E1-T317I C-D180N, E1-T317I, C-D180N, HH E2-T402K, HH E1-T317I C-D180N, HH E1-T317I, and HH C-D180N. The resulting infectious clones were validated by sequencing of the entire structural protein region and used to produce viral RNAs.

To define which mutation(s) were responsible for the improved growth of the revertants, BHK cells were electroporated with the indicated RNAs and incubated at 37°C. The media were collected at the indicated times, and infectious virus was quantitated by a plaque assay. Similar to our previous results, H348/352A growth at 24 hpi was decreased ∼1.4 logs from WT (Fig. 2A and B). In the WT background, both E2-T402K and E1-T317I mutants showed growth comparable to that of the WT, while the E1-T317I C-D180N and C-D180N mutants showed decreased growth (∼0.2 and ∼0.5 logs, respectively). In the H348/352A background, the E2-T402K, E1-T317I C-D180N, and E1-T317I mutations all produced improved growth, with increases of ∼0.7 logs from H348/352A, but were still decreased by ∼0.7-0.8 logs compared to WT. In contrast, growth of the HH C-D180N mutant was strongly inhibited, with decreases of ∼3.3 logs compared to WT and ∼1.9 logs compared to H348/352A at 24 hpi. Plaque assays performed on viruses produced at 12 h postelectroporation showed increased plaque sizes for those mutants with improved virus growth (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Growth of mutants derived from infectious clones. Viral RNAs were generated from infectious clone constructs containing the indicated revertant mutations (see also Table 1). BHK cells were electroporated with WT or mutant RNA and cultured at 37°C, and the media were harvested at the indicated times. Infectious virus production was quantitated by plaque assay. (A) Growth curves shown are the average of two experiments. (B) Comparison of virus growth at 24 hpi, with the range indicated by the bars (data from panel A).

Assembly of E2-T402K and E1-T317I.

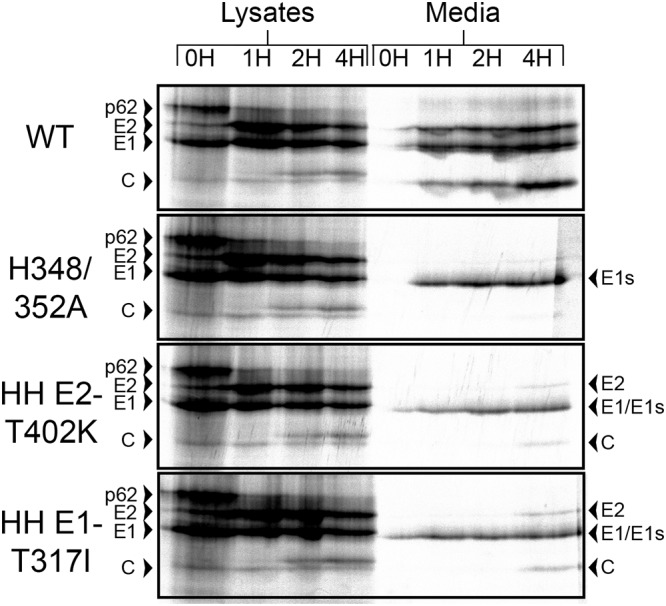

Since the E2-T402K and E1-T317I mutations significantly compensated for the reduction in growth of H348/352A, we investigated whether these mutations could reduce the assembly defect previously described (21). BHK cells were infected with the indicated viruses, incubated at 37°C for 5 h, pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine-cysteine, and chased for 0 to 4 h. The cell media and lysates were immunoprecipitated with E1/E2 polyclonal antibody, using a detergent-free buffer for the medium samples, and evaluated by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging.

All samples showed comparable production of p62 and E1 in the cell lysates and similar kinetics of p62 processing to E2 (Fig. 3). The chase media from the WT-infected cells clearly showed the production of intact virus. As previously observed, the chase media from H348/352A-infected cells contained only E1s, a soluble form of E1 that is produced by a number of nonbudding alphavirus mutants (9, 23). When H348/352A was present with either E2-T402K or E1-T317I, the infected cells produced E1s, but small amounts of E2, E1, and capsid were observed in the 4-h chase samples (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Assembly of HH rescue mutants. BHK cells were infected with WT, H348/352A, or the indicated H348/352A rescue mutants at a multiplicity of 10 PFU/cell for 5 h and then pulse-labeled for 30 min with [35S]methionine-cysteine and chased for the indicated times. Cell lysates and media were harvested at each time point, and samples were immunoprecipitated with an E1/E2 polyclonal antibody and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Media samples were immunoprecipitated in the absence of detergent to allow retrieval of intact virus particles. The data shown are representative of two experiments.

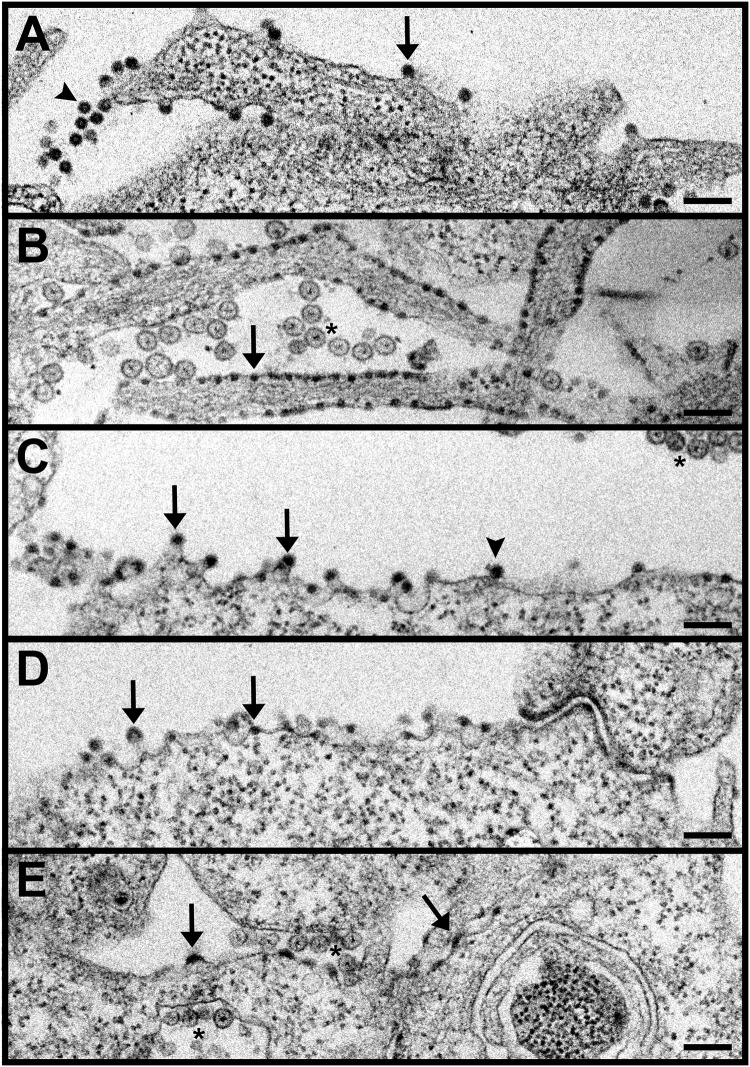

We then performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of BHK cells infected for 8 h with WT virus, the H348/352A mutant, or the HH E2-T402K, HH E1-T317I, or HH C-D180N mutants (Fig. 4). As previously observed (21), the WT-infected cells showed abundant nucleocapsids budding from the plasma membrane, as well as free virus particles, while H348/352A mutant-infected cells showed numerous nucleocapsids under the plasma membrane but little budding or released virus (Fig. 4A versus 4B). The HH E1-T317I-infected cells showed nucleocapsids under the plasma membrane and increases in both virus budding and free virus particles of apparent WT morphology (Fig. 4C). The HH E2-T402K-infected cells also showed increased particle budding and free virus (Fig. 4D). Cells infected with the HH C-D180N mutant showed areas of apparent capsid protein density and some nucleocapsids at the plasma membrane, but little budding virus (Fig. 4E). Virus particles/image and (particles + budding virus)/image were determined for each virus; for both criteria the frequency was WT > HH E1-T317I > HH E2-T402K > HH C-D180N > H348/352A. This rough ranking thus supports an increase in virus budding for both the HH E1 and HH E2 revertants.

FIG 4.

TEM of SFV-infected cells. BHK cells were infected with WT SFV (A), the H348/352A mutant (B), the HH E1-T317I mutant (C), the HH E2-T402K mutant (D), or the HH C-D180N mutant (E). Infection was continued for 8 h, and the cells were fixed and processed for TEM. A representative image of each sample is shown. Arrows indicate nucleocapsids/capsid proteins at the plasma membrane, arrowheads indicate budded virus particles, and asterisks indicate replication spherules. Scale bars, 200 nm.

Together, our data indicate that the E2-T402K and E1-T317I revertant mutations partially reverse the H348/352A assembly phenotype, thereby explaining the observed improvement in virus growth. Our data also argue that the rescue mutations do not act by increasing the formation of infectious capsid-deficient microvesicles, which can arise during late stages of virus infection (24).

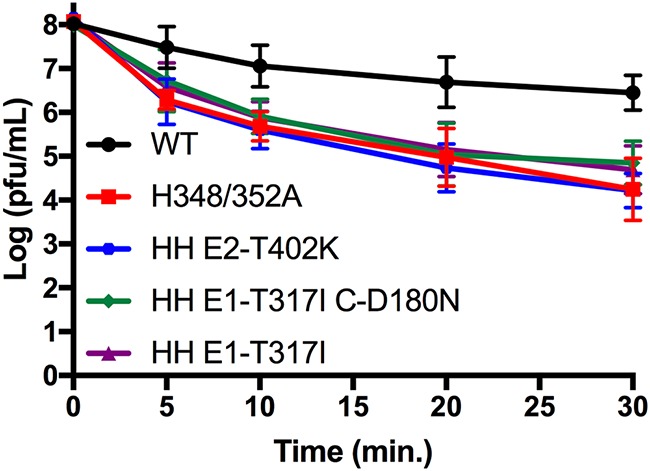

Thermostability effects of E2-T402K, E1-T317I, and E1-T317I C-D180N.

The H348/352A mutations were found to strongly decrease virus thermostability (21). We compared the thermostability of WT, H348/352A, and H348/352A virus containing the indicated revertant mutations. Virus stocks were incubated at 50°C for the indicated times and analyzed by plaque assay. All samples exhibited temperature sensitivity at 50°C, with WT titers decreasing by >1.5 log after a 30-min incubation (Fig. 5). As previously seen, H348/352A was more strongly affected by temperature, showing a >3.8-log decrease in titer by 30 min. The HH E2-T402K, HH E1-T317I, and HH E1-T317I C-D180N mutants displayed a similar phenotype, with decreases of >3.9, >3.4, and >3.1 logs, respectively. The differences in titer reduction between H348/352A and H348/352A carrying the revertant mutations were not statistically significant (P > 0.4 at 30 min). Thus, the revertant mutations caused partial rescue of H348/352A growth and assembly but did not change its thermostability.

FIG 5.

Thermostability of HH rescue mutants. Virus stocks of WT, H348/352A, or the indicated H348/352A rescue mutants were diluted to titers of 1 × 108 PFU/ml and incubated at 50°C for the indicated times. Infectious virus was quantitated by a plaque assay. The results shown are means and standard deviations from three to four independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our prior studies showed that alanine substitutions of E2 H348/H352 inhibit SFV growth and budding and decrease virus particle thermostability (21). We characterized here second-site mutations that partially rescue the growth of the E2 H348/352A double mutant. Sequence analysis of eleven independent revertants revealed an E2 endodomain mutation, four mutations in E1 domains I to III, two mutations in the E1 juxtamembrane stem region, and three capsid mutations that occurred together with E1 mutations. Although prior structural analysis showed that the E2 D-loop residues H348/H352 interact with the highly conserved residues S403 and W409 in the E1 stem (21), we did not isolate revertants mutated at these positions, perhaps reflecting their roles in multiple D-loop interactions.

We investigated the mutations in two revertants, E2-T402K and E1-T317I C-D180N, in detail. Our results show that the E2-T402K and E1-T317I mutations increased the growth and assembly of the H348/352A mutant and caused no deleterious effects in the WT background. In contrast, the C-D180N mutation produced a small decrease in WT virus growth and a significant decrease in H348/352A growth. None of the mutations increased the thermostability of H348/352A virus.

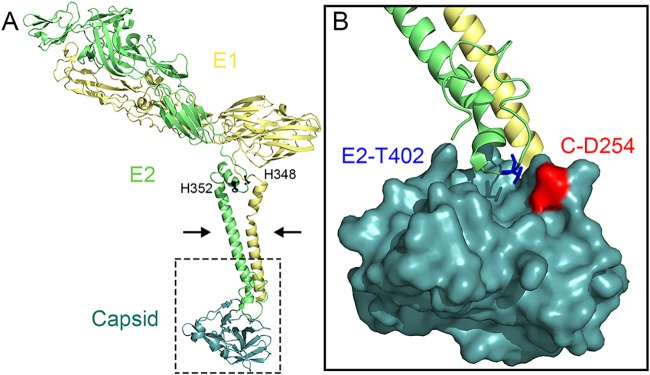

Consideration of the alphavirus structure suggests possible mechanisms for the effects of these mutations. The E2-T402K mutation was independently isolated three times. This mutation is located within the E2 endodomain (Fig. 6), just C terminal to the E2 motif 399Tyr-X-Leu401 that interacts with the hydrophobic pocket of the capsid protein and is required for virus budding (5–8). E2-T402 is positioned close to capsid residue D254 (Fig. 6B), and substitution of a lysine at E2-402 could strengthen ionic interactions with D254. This may increase the stability of the E2-capsid interaction or change the conformation in this region. While not affecting the growth of the WT virus, the E2-T402K mutation promoted virus growth in the H348/352A mutant background, suggesting that the H348/352A mutations affect E2-capsid interactions. It is intriguing that the E2 D-loop region can impact capsid interaction, since this suggests that effects of the H348/352A mutations are transmitted from the D-loop, through the transmembrane domain, to the C-terminal endodomain of E2 (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Location of SFV E2-T402K mutation. Shown are the E1 (yellow), E2 (green), and capsid (teal) proteins extracted from the atomic model built for the alphavirus surface glycoprotein shell and nucleocapsid shell from CHIKV, as based on the CHIKV cryo-EM reconstructions of CHIKV VLPs to 5-Å resolution (PDB access 3J2W). (A) The E2 residues H348 and H352 in the juxtamembrane D-loop are indicated by black sticks, the E2 and E1 transmembrane helices are indicated by arrows, and the E2 endodomain rescue mutation is in the boxed region. (B) Expanded view of the CHIKV E2-capsid interaction from the boxed region in panel A (at a slightly tilted angle for clarity). The capsid is shown in a surface view; E2-T402 (which is K402 in the revertant) is shown as a blue stick, and capsid D254 is shown in red. Note that for clarity the SFV residue numbering is used here for CHIKV E2 and capsid. All images were prepared using PyMOL software (37).

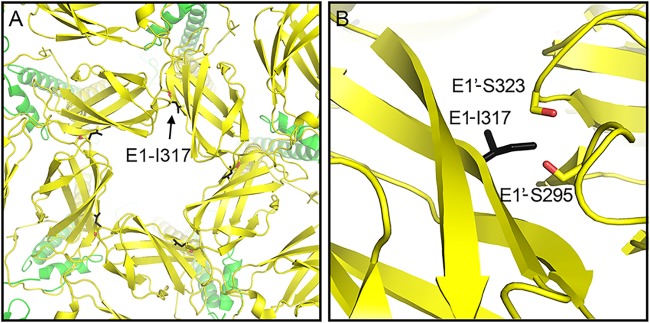

The E1-T317I mutation was independently isolated three times, each time together with an additional mutation in either capsid or E1. E1-T317 lies in domain III of E1 at a site previously described to make E1-E1 contacts between trimers at the 5-fold axis of symmetry (22). In CHIKV, E1-317 is an isoleucine that makes polar contacts with residues E1′-S295 and E1′-S323 in the adjacent trimer (Fig. 7). In SFV both E1-317 and E1′-295 are threonines, whereas E1′-323 is an asparagine, residues that would support polar contacts between adjacent E1 proteins at the 5-fold axis. The SFV E1-T317I revertant mutation substitutes the CHIKV residue at this position, and we suggest that this change would alter the SFV E1 intertrimer contacts and thus affect the architecture of the glycoprotein lattice. While interspike contacts are mediated by E1, our results suggest an indirect role for the E2 D-loop, in which D-loop-E1 contacts promote the proper orientation of E1 and thus support lattice formation on the virus envelope.

FIG 7.

Interactions of E1-T317 in the glycoprotein lattice. Shown are segments corresponding to E1 (yellow) and E2 (green) extracted from the atomic model built for the alphavirus surface glycoprotein shell from CHIKV, based on the cryo-EM reconstructions of CHIKV VLPs to 5-Å resolution (PDB access 3J2W). (A) CHIKV E1 interactions at the 5-fold axis of symmetry. The highlighted residues are from E1 belonging to five different trimeric E2/E1 spikes coming together at one vertex. E1-I317 is shown as a black stick image, and S323 and S295 on the adjacent E1′ are shown as sticks with the side chain oxygen atoms in red. Note that the E1 residue numbering is the same for SFV and CHIKV, but these residues are T317, T295, and N323 in WT SFV. (B) Expanded view (at a slightly tilted angle for clarity) of the CHIKV E1 domain III interactions involving these three residues. CHIKV E1-I317 is in position to interact with the adjacent E1′ via S323 and S295. All images were prepared using PyMOL software (37).

The capsid protein D180N mutation slightly decreased WT virus growth but was more deleterious in the H348/352A background, at least at late times of infection. Capsid D180 is positioned pointing into the interior of the nucleocapsid core, and it is unclear how a C-D180N substitution would disrupt growth in the E2-H348/352A background. This growth inhibition was abrogated when E1-T317I was present with C-D180N, suggesting that E1-T317I likely occurred as a primary mutation that allowed subsequent mutation of C-D180. Since SFV E1 does not appear to interact with capsid (25), we speculate that the effects of the E1-T317I mutation on the glycoprotein lattice indirectly affect E2-capsid interactions to provide an environment in which the C-D180N mutation was not deleterious.

It is interesting that none of the revertant mutations we tested rescued the decreased thermostability of the H348/352A virus mutant. This might suggest that the architecture of the envelope protein lattice needed for virus budding does not necessarily promote particle stability, but it could also reflect the difference in sensitivity of the assays for infectious virus production versus thermoinactivation.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) reconstructions of alphavirus cytoplasmic nucleocapsids, nucleocapsids imaged within virus particles, and nucleocapsids purified from virus particles reveal structural differences (26, 27). Comparative studies also suggest differences in sedimentation properties and RNase sensitivity between NCs isolated from infected cells versus those isolated from virus particles (28). Consideration of these and other data suggested that the interaction of the envelope proteins with the capsid proteins could promote nucleocapsid maturation during budding of virus particles (5, 11, 29, 30). The importance of envelope interactions in nucleocapsid maturation is in keeping with a temperature-sensitive capsid mutant, in which unstable cytoplasmic nucleocapsids are stabilized upon budding into virus particles (19). In further support of effects of E2-capsid protein interactions during nucleocapsid assembly, a Sindbis capsid protein mutant fails to assemble nucleocapsids in infected cells but assembles nucleocapsids in the absence of the envelope proteins (11). While these data suggest the importance of interactions between the envelope protein lattice and the nucleocapsid, it has been unclear which residues promote envelope lattice formation and budding.

We had earlier hypothesized that the E2 D-loop might play a role in formation of the envelope protein lattice (21). By selecting for revertants of E2 D-loop mutations, we here identified second-site mutations that rescue H348/352A particle production. These mutations affect E2-capsid interactions and the E1-E1 contacts in the glycoprotein lattice. Thus, the residues and conformation of the E2 D-loop promote interactions among all three of the major virus structural proteins, thereby supporting nucleocapsid maturation and virus budding. Recent studies show that neutralizing antibodies to the CHIKV envelope proteins can block virus budding at the plasma membrane (31). The antibodies appear to act by clustering the envelope proteins into densely packed arrays. Interestingly, such clustering appears to also affect the structure of the nucleocapsids at the plasma membrane (31). It is intriguing to speculate that this mechanism of antibody neutralization reflects the critical interactions within the external glycoprotein lattice and their propagation to the internal capsid protein shell, interactions in which the E2 D-loop plays an important role.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

BHK-21 cells were cultured at 37°C in complete BHK medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium [DMEM] plus 5% fetal bovine serum, 10% tryptose phosphate broth, 100 U penicillin/ml, and 100 μg streptomycin/ml).

Viral RNAs were prepared by in vitro transcription of the WT pSP6-SFV4 infectious clone (32) or mutant clones constructed as described below. To generate virus stocks, RNAs were electroporated into BHK cells (32), and the cells were cultured in infection medium (minimal essential medium with 0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 mM HEPES [pH 8.0]). Media were harvested at 24 hpi and pelleted at 20,800 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. All plaque assays were performed using BHK cells.

Revertant selection.

Revertants of the H348/352A mutant were selected by electroporating BHK cells with mutant RNA and plating in individual 60-mm culture dishes, followed by incubation at 37°C for ∼48 h. Progeny viruses in the culture medium were then serially passaged by infecting fresh cells at a multiplicity of ∼0.01 PFU/cell and incubating them at 37°C for approximately 24 to 48 h. Passaging was continued for seven serial passages, at which time larger plaques appeared. Viruses were then plaque purified from each independent plate and amplified for 24 h in infection media. Cell media were collected, and viruses were pelleted through a 20% sucrose cushion by centrifugation at 4°C for 3 h in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 35,000 rpm. Virus pellets were resuspended in TN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.4]). Viral RNA was extracted using a MagMAX viral RNA isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse transcribed using AMV-RT (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR using Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) with the following primers: forward, 5′-CCAGGACGACTCCTTGGC-3′; and reverse, 5′-CAATTTTCTTGCTATATCAATGCC-3′. Sequencing of the entire structural protein coding region was then performed to determine the sequence at positions E2-H348/352 and identify changes from the starting mutant virus sequence (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ).

Generation of revertant infectious clones.

Mutations identified from revertant sequencing were analyzed in the context of both the WT and H348/352A pSP6-SFV4 infectious clones. Mutations were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using Gibson assembly (33, 34). The infectious clone was digested by NsiI and XmnI (E2-T402K and E1-T317I), XbaI and XmnI (E1-T317I C-D180N), or XbaI and NsiI (C-D180N) to generate the vector backbone. Overlapping fragments were generated by PCR using primers determined by the NEBuilder assembly tool, v1.12.15 (New England Biolabs, Inc.). Assembly was performed using the Gibson assembly master mix and transformed into NEB competent cells (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA). Revertant clones were verified by restriction digest with EcoRI, NsiI, and SpeI and by sequencing of the entire structural protein coding region (Genewiz).

Virus growth assays.

BHK cells were either electroporated with viral RNAs derived from infectious clones or infected at a multiplicity of 1 PFU/cell using plaque-purified virus stocks from the revertant selection. Cells were grown in infection media at 37°C, and cell media were collected at the indicated time points and pelleted to remove cell debris, as described above. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay using two independent dilution series for each time point.

Assembly assays.

BHK cells were infected at a multiplicity of 10 PFU/cell with WT, H348/352A, HH E2-T402K, and HH E1-T317I viruses. At 4.5 hpi (based on the addition of virus at time zero), cells were washed in cysteine/methionine-free medium and starved at 37°C for 20 min. Cells were pulse-labeled with 100 μCi/ml [35S]methionine-cysteine for 30 min at 37°C, followed by incubation in chase media (DMEM, 10 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 100 U penicillin/ml, and 100 μg streptomycin/ml, with 10× excess cysteine and methionine) for 0 to 4 h. Cell media were collected, centrifuged to remove debris as described above, and immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal antibody against E1 and E2 in the absence of detergent. Cell lysates were harvested in lysis buffer (TN buffer with 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 50 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mg/ml BSA, 1% aprotinin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), centrifuged as described above to remove cell nuclei, and immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antibody to E1 and E2 using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for washes (35). Media and lysate samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and imaged with a Fujifilm FLA-5100 phosphorimager (Fujifilm Life Science, Stamford, CT).

Electron microscopy.

BHK cells were infected with WT SFV, the H348/352A mutant, and the HH E2-T402K, HH E1-T317I, and HH C-D180N viruses at a multiplicity of 10 PFU/cell, followed by incubation for 8 h at 37°C. The cells were then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde–2% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM cacodylate buffer for 30 min at room temperature. The Einstein Analytical Imaging facility embedded and processed the samples, and TEM images were acquired using a JEOL 1400 Plus TEM apparatus (SIG no. 1S10OD016214) under double-blind conditions. Images at the same magnification (n ≥ 5 for each sample) were then independently evaluated by four individuals without knowledge of sample identity.

Virus thermostability.

Virus stocks were diluted to 1 × 108 PFU/ml in infection media and incubated at 50°C for 0 to 30 min. After incubation, the samples were transferred to ice, and titers were immediately determined by plaque assay. Statistics were calculated by two-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons using Prism (36).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Félix Rey for helpful discussions and insights into the alphavirus structural analysis, as well as for Fig. 7, which he kindly provided. We also thank Judy Wan for help with figure preparation. We thank the members of our lab for helpful discussions and Rebecca Brown for comments on the manuscript. We thank the Einstein Analytical Imaging Facility for preparation of the TEM samples, and Rebecca Brown and Elisa Frankel for contributions to the analysis of the electron microscopy data.

This study was supported by a grant to M.K. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI075647) and by Cancer Center Core Support Grant NIH/NCI P30-CA13330. E.A.B. was supported in part by the MSTP Training Grant T32 GM007288.

The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuhn RJ. 2013. Togaviridae, p 629–650. In Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin DE. 2013. Alphaviruses, p 651–686. In Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukhopadhyay S, Zhang W, Gabler S, Chipman PR, Strauss EG, Strauss JH, Baker TS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2006. Mapping the structure and function of the E1 and E2 glycoproteins in alphaviruses. Structure 14:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown RS, Wan JJ, Kielian M. 2018. The alphavirus exit pathway: what we know and what we wish we knew. Viruses 10:E89. doi: 10.3390/v10020089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S, Owen KE, Choi H-K, Lee H, Lu G, Wengler G, Brown DT, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ. 1996. Identification of a protein binding site on the surface of the alphavirus nucleocapsid and its implication in virus assembly. Structure 4:531–541. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen KE, Kuhn RJ. 1997. Alphavirus budding is dependent on the interaction between the nucleocapsid and hydrophobic amino acids on the cytoplasmic domain of the E2 envelope glycoprotein. Virol 230:187–196. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao H, Lindqvist B, Garoff H, von Bonsdorff C-H, Liljeström P. 1994. A tyrosine-based motif in the cytoplasmic domain of the alphavirus envelope protein is essential for budding. EMBO J 13:4204–4211. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skoging U, Vihinen M, Nilsson L, Liljeström P. 1996. Aromatic interactions define the binding of the alphavirus spike to its nucleocapsid. Structure 4:519–529. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffus WA, Levy-Mintz P, Klimjack MR, Kielian M. 1995. Mutations in the putative fusion peptide of Semliki Forest virus affect spike protein oligomerization and virus assembly. J Virol 69:2471–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akahata W, Yang ZY, Andersen H, Sun S, Holdaway HA, Kong WP, Lewis MG, Higgs S, Rossmann MG, Rao S, Nabel GJ. 2010. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med 16:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nm.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder JE, Berrios CJ, Edwards TJ, Jose J, Perera R, Kuhn RJ. 2012. Probing the early temporal and spatial interaction of the Sindbis virus capsid and E2 proteins with reverse genetics. J Virol 86:12372–12383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01220-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tellinghuisen TL, Hamburger AE, Fisher BR, Ostendorp R, Kuhn RJ. 1999. In vitro assembly of alphavirus cores by using nucleocapsid protein expressed in Escherichia coli. J Virol 73:5309–5319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tellinghuisen TL, Kuhn RJ. 2000. Nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of the nucleocapsid protein of Sindbis virus. J Virol 74:4302–4309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.9.4302-4309.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman PR, Hong EM, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2002. In vitro-assembled alphavirus core-like particles maintain a structure similar to that of nucleocapsid cores in mature virus. J Virol 76:11128–11132. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11128-11132.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng F, Mukhopadhyay S. 2011. Generating enveloped virus-like particles with in vitro assembled cores. Virol 413:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsell K, Xing L, Kozlovska T, Cheng RH, Garoff H. 2000. Membrane proteins organize a symmetrical virus. EMBO J 19:5081–5091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skoging-Nyberg U, Liljeström P. 2001. M-X-I motif of Semliki Forest virus capsid protein affects nucleocapsid assembly. J Virol 75:4625–4632. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4625-4632.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lulla V, Kim DY, Frolova EI, Frolov I. 2013. The amino-terminal domain of alphavirus capsid protein is dispensable for viral particle assembly but regulates RNA encapsidation through cooperative functions of its subdomains. J Virol 87:12003–12019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01960-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Y, Kielian M. 2015. An alphavirus temperature-sensitive capsid mutant reveals stages of nucleocapsid assembly. Virol 484:412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendes A, Kuhn RJ. 2018. Alphavirus nucleocapsid packaging and assembly. Viruses 10:E138. doi: 10.3390/v10030138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrd EA, Kielian M. 2017. An alphavirus E2 membrane-proximal domain promotes envelope protein lateral interactions and virus budding. mBio 8:e01564-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voss JE, Vaney MC, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, Girard-Blanc C, Crublet E, Thompson A, Bricogne G, Rey FA. 2010. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature 468:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Garoff H. 1992. Role of cell surface spikes in alphavirus budding. J Virol 66:7089–7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiz-Guillen M, Gabev E, Quetglas JI, Casales E, Ballesteros-Briones MC, Poutou J, Aranda A, Martisova E, Bezunartea J, Ondiviela M, Prieto J, Hernandez-Alcoceba R, Abrescia NG, Smerdou C. 2016. Capsid-deficient alphaviruses generate propagative infectious microvesicles at the plasma membrane. Cell Mol Life Sci 73:3897–3916. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2230-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barth BU, Suomalainen M, Liljeström P, Garoff H. 1992. Alphavirus assembly and entry: role of the cytoplasmic tail of the E1 spike subunit. J Virol 66:7560–7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb K, Lokesh GL, Sherman M, Watowich S. 2010. Structure of a Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus assembly intermediate isolated from infected cells. Virol 406:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paredes A, Alwell-Warda K, Weaver SC, Chiu W, Watowich SJ. 2003. Structure of isolated nucleocapsids from Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and implications for assembly and disassembly of enveloped virus. J Virol 77:659–664. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.659-664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coombs K, Brown B, Brown DT. 1984. Evidence for a change in capsid morphology during Sindbis virus envelopment. Virus Res 1:297–302. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(84)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pletnev SV, Zhang W, Mukhopadhyay S, Fisher BR, Hernandez R, Brown DT, Baker TS, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ. 2001. Locations of carbohydrate sites on alphavirus glycoproteins show that E1 forms an icosahedral scaffold. Cell 105:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jose J, Przybyla L, Edwards TJ, Perera R, Burgner JW, Kuhn RJ. 2012. Interactions of the cytoplasmic domain of Sindbis virus E2 with nucleocapsid cores promote alphavirus budding. J Virol 86:2585–2599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05860-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin J, Galaz-Montoya JG, Sherman MB, Sun SY, Goldsmith CS, O’Toole ET, Ackerman L, Carlson LA, Weaver SC, Chiu W, Simmons G. 2018. Neutralizing antibodies inhibit Chikungunya virus budding at the plasma membrane. Cell Host Microbe 24:417–428.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liljeström P, Lusa S, Huylebroeck D, Garoff H. 1991. In vitro mutagenesis of a full-length cDNA clone of Semliki Forest virus: the small 6,000-molecular-weight membrane protein modulates virus release. J Virol 65:4107–4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson DG, Smith HO, Hutchison CA, Venter JC, Merryman C. 2010. Chemical synthesis of the mouse mitochondrial genome. Nat Methods 7:901–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao M, Kielian M. 2006. Functions of the stem region of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein during virus fusion and assembly. J Virol 80:11362–11369. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01679-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivashchenko R, Bykov I, Datsko A, Dolgaya L, Goodz A, Shayna A. 2017. Prism7 for Mac OS X. v7.0c. GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 37.PyMOL. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, v1.2r2. Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]