Measles virus can invade the central nervous system (CNS) and cause severe neurological complications, such as MIBE and SSPE. However, mechanisms by which MeV enters the CNS and triggers the disease remain unclear. We analyzed viruses from brain tissue of individuals with MIBE or SSPE, infected during the same epidemic, after the onset of neurological disease. Our findings indicate that the emergence of hyperfusogenic MeV F proteins is associated with infection of the brain. We also demonstrate that hyperfusogenic F proteins permit MeV to enter cells and spread without the need to engage nectin-4 or CD150, known receptors for MeV that are not present on neural cells.

KEYWORDS: central nervous system infections, measles, viral fusion

ABSTRACT

During a measles virus (MeV) epidemic in 2009 in South Africa, measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE) was identified in several HIV-infected patients. Years later, children are presenting with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). To investigate the features of established MeV neuronal infections, viral sequences were analyzed from brain tissue samples of a single SSPE case and compared with MIBE sequences previously obtained from patients infected during the same epidemic. Both the SSPE and the MIBE viruses had amino acid substitutions in the ectodomain of the F protein that confer enhanced fusion properties. Functional analysis of the fusion complexes confirmed that both MIBE and SSPE F protein mutations promoted fusion with less dependence on interaction by the viral receptor-binding protein with known MeV receptors. While the SSPE F required the presence of a homotypic attachment protein, MeV H, in order to fuse, MIBE F did not. Both F proteins had decreased thermal stability compared to that of the corresponding wild-type F protein. Finally, recombinant viruses expressing MIBE or SSPE fusion complexes spread in the absence of known MeV receptors, with MIBE F-bearing viruses causing large syncytia in these cells. Our results suggest that alterations to the MeV fusion complex that promote fusion and cell-to-cell spread in the absence of known MeV receptors is a key property for infection of the brain.

IMPORTANCE Measles virus can invade the central nervous system (CNS) and cause severe neurological complications, such as MIBE and SSPE. However, mechanisms by which MeV enters the CNS and triggers the disease remain unclear. We analyzed viruses from brain tissue of individuals with MIBE or SSPE, infected during the same epidemic, after the onset of neurological disease. Our findings indicate that the emergence of hyperfusogenic MeV F proteins is associated with infection of the brain. We also demonstrate that hyperfusogenic F proteins permit MeV to enter cells and spread without the need to engage nectin-4 or CD150, known receptors for MeV that are not present on neural cells.

INTRODUCTION

In 2009-2010, a single measles virus (MeV) strain (genotype B3) was responsible for an extensive measles outbreak in South Africa (1). During this epidemic, numerous HIV-infected patients were diagnosed with measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE) (2), constituting the largest MIBE case series ever reported. Now, several years later, children who were infected with MeV during the outbreak are developing subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) (3).

The early events enabling MeV to establish brain infection remain to be elucidated, since samples are mainly obtained postmortem. Neurons, which are particularly targeted by neurotropic MeV, do not express known MeV receptors (i.e., CD150 and nectin-4). However, neuroselected or neuroadapted variants spread in the central nervous system (CNS). Several mutations in the fusion complex (composed of the receptor binding protein H and the fusion protein F) have been reported, mainly in the fusion protein of neurotropic MeV (4–6). The viruses bearing these F proteins infect and spread without known measles receptors (4–6).

MIBE occurs shortly after exposure to MeV from several weeks to months following infection, typically in highly immunocompromised patients. In a previous study, viral sequences obtained from the brains of HIV-infected patients who died of MIBE were analyzed to identify mutations correlated with neurovirulence (7). In samples from two out of three MIBE patients, the extracellular domain of the F protein had an L454W substitution that conferred a hyperfusogenic phenotype to MeV (8). SSPE, in contrast, occurs much later after exposure, on average 6 to 8 years, in immunocompetent patients. This syndrome is characterized by MeV brain infection and is associated with hypermutated genomic RNA and viral transcripts, as well as defects in particle assembly (9–11). These mutations often affect the matrix protein responsible for viral assembly and budding (9, 12–15).

To investigate the genetic underpinnings of MeV brain infection, we analyzed viral sequences isolated from an HIV-infected male child with SSPE who contracted MeV (under 6 months of age) during the 2009-2010 South African outbreak and presented with intractable seizures and deteriorating nervous system function 4 years later. The infant had been vertically infected with HIV and was on antiretroviral therapy (ART) from the age of 2.5 months, with near-normal CD4 counts and suppressed HIV load at the time of clinical presentation (3). The SSPE diagnosis was based on high MeV antibody titers in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a history of measles in the first 6 months of life, and compatible electroencephalogram and magnetic resonance imaging results. He experienced a rapid decline in neurological function and died from aspiration pneumonia 8 months after initial presentation.

Viral sequence analyses showed close homology with the epidemic wild-type and MIBE-related strains and additional genetic changes characteristic of SSPE.

We compared the functional effects of mutations in the MeV fusion complex in the SSPE, MIBE, and wild-type B3 viruses from the original outbreak. The F proteins of both SSPE and MIBE viruses have a lower thermal stability than the wild type and can promote fusion independently of H binding to known MeV receptors.

RESULTS

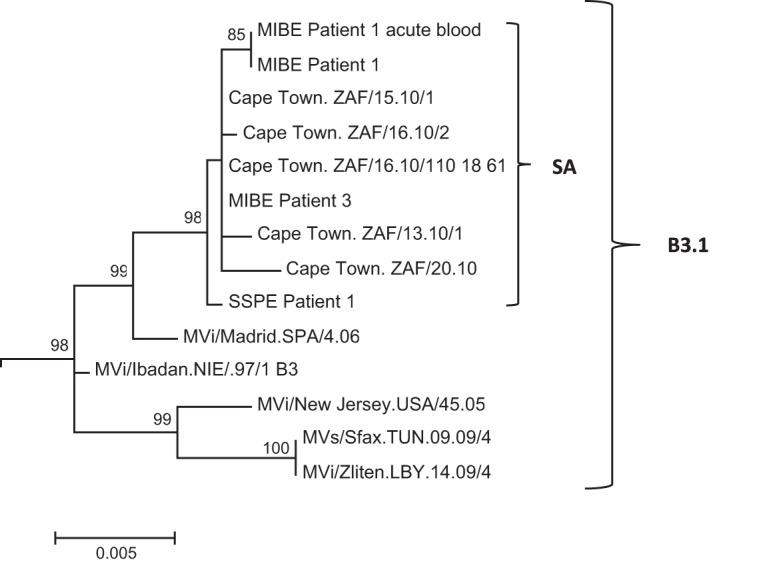

Phylogenetic analysis confirms close relationship to epidemic strain.

The SSPE sequences were found to be closely related to the 2009-2010 B3 epidemic strain and MIBE sequences in a phylogenetic tree of the H gene (nucleotide positions 7496 to 9124) using maximum likelihood analysis (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree of H gene (nucleotide positions 7496 to 9124) generated by maximum likelihood analysis of MeV from the SSPE case, patients with MIBE, patients who had acute measles infection during the measles epidemic of 2009-2010 in South Africa, and reference sequences. Reference sequences of other MeV genotype B3.1 viruses were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database and are indicated by accession numbers. Bootstrap values greater than 75% are indicated at the nodes of the tree. The branch lengths are proportional to the evolutionary distances, as shown on the scale.

Sequence analysis reveals genetic features typical of SSPE.

Sixty mutations were detected in the SSPE viral sequence relative to the epidemic B3 reference strain (28 U-C, 4 A-G, 10 C-U, 9 G-A, 1 U-G, 4 C-A, and 1 A-U), with 28 being nonsynonymous (all nucleotide substitutions are annotated in Table S1 in supplemental material). Variation relative to the reference consensus sequence was highest in the first 3 genes, increasing from 0.47% for N, 0.60% for P, and 0.89% for the M gene. The number of mutations declined progressively over the last 3 genes, namely, 0.38% for F, 0.31% for H, and 0.23% for the large protein (L) gene. In comparison, there were approximately 10 times fewer mutations in the MIBE sequences.

Hallmarks of the SSPE sequences included hypermutation, in particular U-to-C substitutions, in the N, P, and M genes. There appear to have been three events. One was at the N-P gene border (6 mutations between residues 1525 and 1778, of which 5 are silent). The second event occurs at the end of the P gene (4 mutations between residues 2722 and 2958, of which 2 are silent). The third is found in the M gene (9 mutations between residues 3450 and 4280, of which only 2 are silent; 4 of the 7 amino acid changes affect tyrosines). In all probability the last hypermutation event ablated the function of the matrix protein. U-to-C mutations occurred at a lower frequency in the latter part of the genome. In the MIBE-related sequences, U-to-C mutations were also most prominent in the N, P, and M genes.

Mutations in the H/F glycoproteins of MeV isolated from the brain of an SSPE patient.

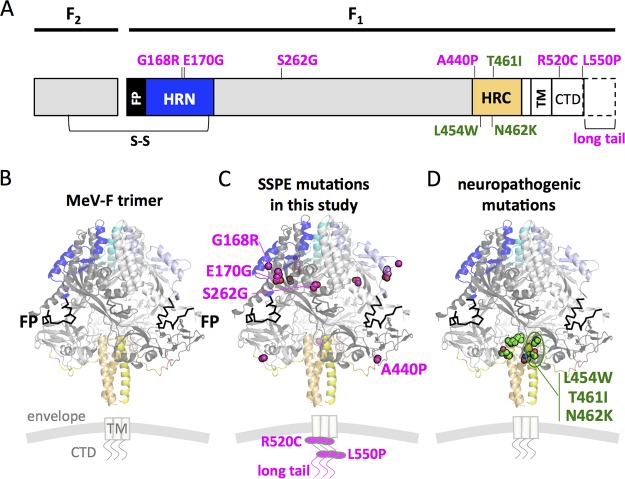

Mutations in the F proteins are shown on the sequence and on the prefusion structures (16) in Fig. 2. The F sequence from the clinical sample (SSPE F) had 6 amino acid changes (G168R, E170G, S262G, A440P, R520C, and L550P) compared to the sequence of wild-type epidemic strain B3 MeV F. One additional mutation abolished a stop codon, leading to a longer C-terminal cytoplasmic tail, referred to here as long tail (LT). In contrast to substitutions in the C-terminal heptad repeat (HRC) region of the F previously described in other neuropathogenic strains (i.e., L454W, T461I, and N462K) (6, 7), this SSPE sequence had two substitutions (G168R and E170G) in the N-terminal heptad repeat (HRN), one (A440P) in the N-terminal border of the HRC and two (R520C and L550P) in the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD). One additional substitution (S262G) was located at the interface of three protomers and two intramolecular domains near the HRN. This position has been shown to be involved in fusion activation and was previously described in a hyperfusogenic F variant (6). Conversely, compared to related MIBE sequences, only the L454W substitution in the HRC domain was present (Fig. 2). In the H gene of the South African SSPE sequence, 3 nonsynonymous mutations were identified in the cytoplasmic tail (R7Q), stalk domain (R62Q), and β5 blade of the head domain (D530E), the latter forming part of the CD150 receptor binding site (17). In contrast, there were no changes in the H gene in related MIBE sequences.

FIG 2.

Location of substitutions within the F protein from CNS-adapted virus. (A) Schematic representation of fusion protein with relevant regions indicated. FP, fusion peptide; S-S, disulfide bond; HRN and HRC, heptad repeat domains at the N terminus or at the C terminus; TM, transmembrane domain; CTD, cytoplasmic domain. (B) Ribbon diagrams of the measles F model structure in prefusion conformation. The F SSPE clinical sample had a total of 6 mutations compared to sequence of the wild-type B3 strain. Residues G168G and E170G map in the HRN domain, while A440P maps close to the HRC. The residue S262G is in the region between HRN and HRC. Residues R520C and L550P are in the CTD region. One additional mutation abolished the F stop codon and resulted in a 29-amino-acid extension of the CTD (long tail). The SSPE residues are indicated in magenta. Additionally, three substitutions (L454W, T461I, and N462K) localized in the HRC domain, and previously described (6, 7) in neuropathogenic strains, are shown in green.

Both SSPE and MIBE F proteins promote fusion in the absence of MeV receptors.

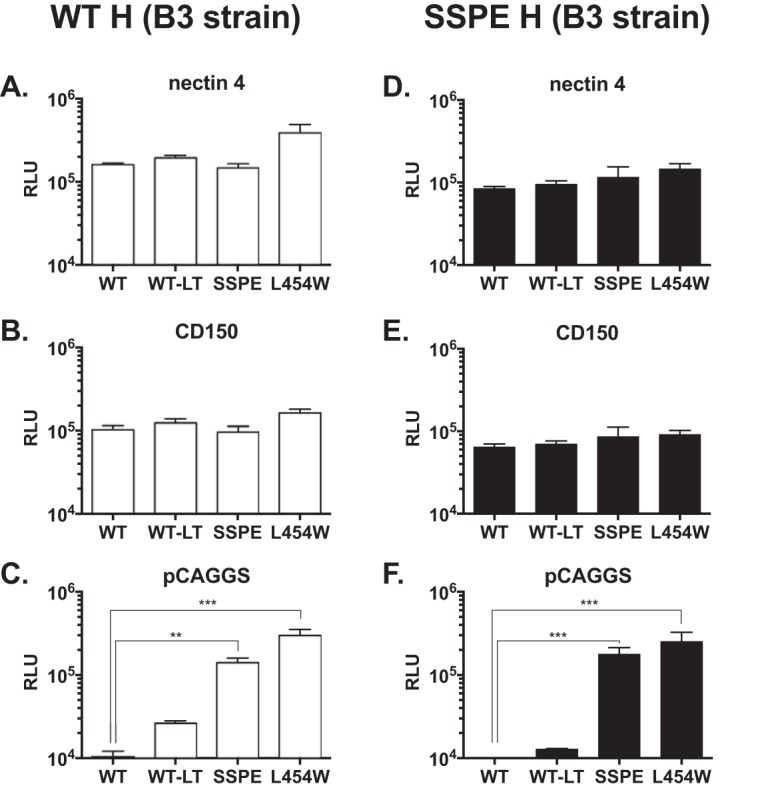

In order to evaluate functional differences between the wild type and the SSPE virus fusion complex, we introduced the SSPE mutations found into the wild-type B3 H and F sequences, as well as the mutation that abolishes the natural stop codon at the end of the F sequence (LT). We then compared the fusion phenotype of the SSPE F to the MIBE F L454W (7). Figure 3 depicts a quantitative assay assessing the fusion properties of these MeV H/F pairs and their requirements for receptor engagement. Coexpression of WT H and F proteins resulted in similar fusion in the presence of nectin-4 and CD150 (Fig. 3). WT F does not fuse in the absence of known MeV receptors, and WT F-LT did not significantly alter the fusion phenotype compared to that of the WT, either in the presence or absence of MeV receptors (Fig. 3). In contrast, SSPE F and MIBE F L454W promote fusion in the absence of the two MeV receptors (8). The SSPE H promotes F-mediated fusion to a lesser extent than wild-type H (Fig. 3A to C and Fig. 3D to F).

FIG 3.

Functional analysis of F/H protein pairs from MeV B3 SSPE clinical sample. The cell-to-cell fusion of 293T cells coexpressing the indicated MeV B3 F protein and MeV B3 H WT (white bars) or MeV B3 H SSPE (black bars) with 293T cells transfected with MeV receptor nectin-4 (A and D), CD150 (B and E), or with an empty vector (C and F) was assessed by a β-Gal complementation assay. The values are expressed as the relative luminescence unit (RLU) averages (with SEM) of results from three independent experiments in triplicate. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-way ANOVA and Fisher’s post hoc test). WT, wild-type F; WT-LT, wild-type F with long cytoplasmic tail; SSPE, F bearing 5 mutated amino acids (G168R, E170G, S262G, A440P, R520C, and L550P) and the ablation of the stop codon that leads to a longer cytoplasmic tail. Levels of expression of the different proteins were comparable (data not shown).

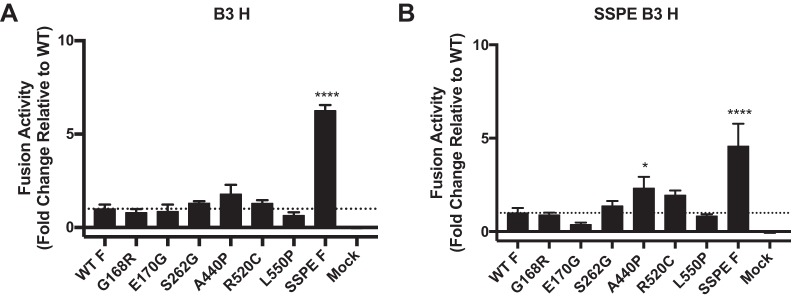

The 6 mutations in SSPE F are cumulatively responsible for the fusion phenotype.

To determine whether any of the 6 substitutions found in the SSPE F were solely responsible for the hyperfusogenic phenotype we observed, we compared each mutation (G168R, E170G, S262G, A440P, R520C, and L550P) individually to wild-type B3 F. In the presence of nectin-4 or CD150, all of the F proteins showed fusion similar to that of wild-type B3 F (Table 1). In the absence of MeV receptors, fusion activity was only detected in the SSPE F bearing all 6 mutations (Fig. 4).

TABLE 1.

Fusion activity of F proteins cotransfected with WT or SSPE patient MeV H in the presence of known MeV receptors

| H/F protein | Fusion activitya: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Nectin-4 | CD150 | |

| WT H | ||

| SSPE F | 1.34 ± 0.11 | 1.32 ± 0.14 |

| G168R | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 1.22 ± 0.10 |

| E170G | 0.97 ± 0.18 | 1.13 ± 0.15 |

| S262G | 1.06 ± 0.17 | 1.18 ± 0.15 |

| A440P | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.09 |

| R520C | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.02 |

| L550P | 0.82 ± 0.11 | 0.80 ± 0.15 |

| SSPE H | ||

| SSPE F | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.17 |

| G168R | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 0.79 ± 0.09 |

| E170G | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.06 |

| S262G | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 0.82 ± 0.04 |

| A440P | 1.00 ± 0.15 | 0.84 ± 0.14 |

| R520C | 1.01 ± 0.06 | 0.88 ± 0.03 |

| L550P | 0.86 ± 0.13 | 0.73 ± 0.04 |

Values are fold change relative to values for WT F.

FIG 4.

Multiply mutated SSPE B3 F has higher fusion activity than any individually mutated F in the absence of MeV host cell receptors. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with the indicated F protein, α-subunit of β-galactosidase, and wild-type B3 MeV H (A) or B3 MeV SSPE H (B). Transfected cells were subsequently overlain with HEK-293T cells expressing the ω-subunit of β-galactosidase for 6 h to allow fusion. Resulting luminescence from β-galactosidase activity was quantified using TECAN Infinite M1000 Pro. Results depict a representative experiment with means and SEM from three biological replicates. Activity of mutants was compared with wild-type B3 F activity by one-way ANOVA. Fusion activities significantly different (P < 0.05) from that of wild-type B3 F are indicated by an asterisk(s).

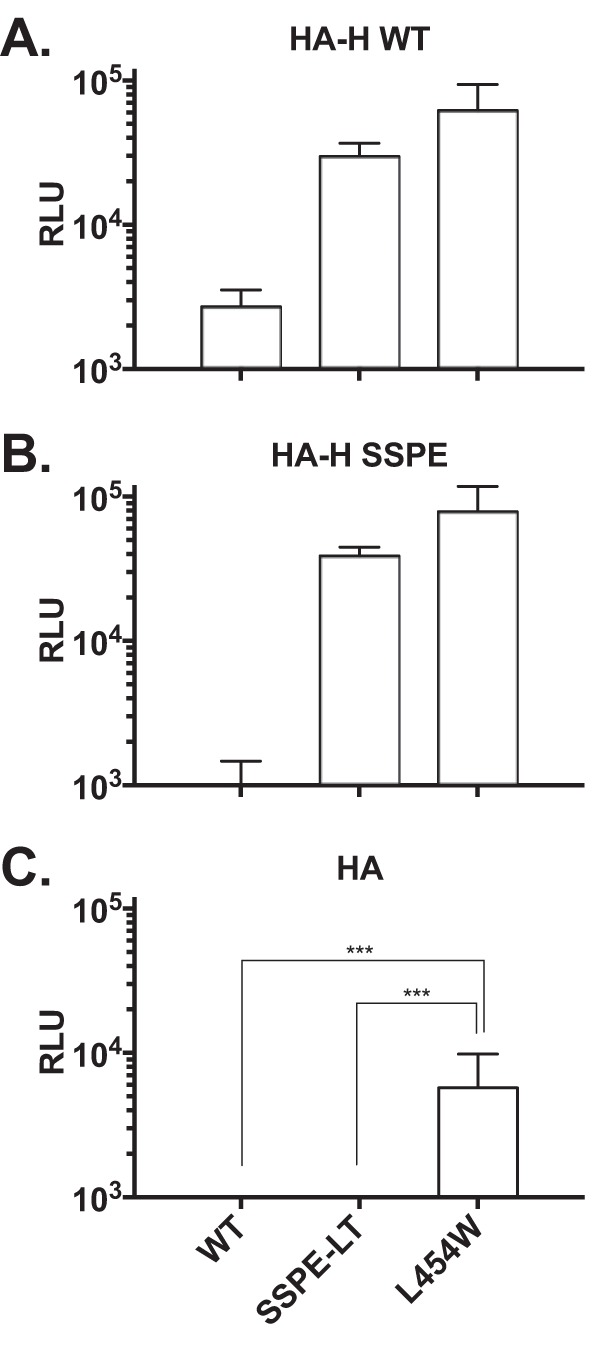

The SSPE F requires the presence of a homotypic protein H in order to fuse, but the MIBE-related F does not.

The MeV H protein has a dual function of tethering the virus to the target cell and activating the F protein. To assess the regulation of fusion promotion by H independently from its tethering function, cells were transfected with uncleaved influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA), in addition to MeV H and F. The HA protein binds sialic acid, ubiquitously expressed on cells, but does not activate MeV F. It was used here to tether the membranes of the effector and target cells as previously done (18–20). The fusion properties of MeV H/F pairs were assessed in the quantitative fusion assay as before but without MeV receptor (nectin-4 and CD150) expression. Effector cells coexpressed influenza HA (HA0) with MeV F (wild-type B3 F, SSPE F-LT, or MIBE F L454W) and MeV H (wild-type B3 H or SSPE H). As expected, no significant fusion was detected when wild-type F was coexpressed with MeV H (WT or SSPE), while the SSPE-LT F still fused at levels similar to those of MIBE F L454W when coexpressed with MeV H (both WT and SSPE) (Fig. 5A and B). We next tested whether, in the absence of H, the SSPE-LT F could still promote membrane fusion. Under these conditions, the SSPE-LT F did not mediate fusion (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that either SSPE-LT F can be activated independently of receptor engagement by H or it requires H engagement to an unknown MeV receptor of low affinity. Also, SSPE-LT F activation is possible only in the presence of H, with similar results obtained for the SSPE F variant without the long tail (data not shown). In contrast, the MIBE L454W F protein shows an inherent ability to mediate fusion even in the absence of H, albeit with lower fusion activity than that observed when H (WT or SSPE) is also expressed, in agreement with previous observations (8).

FIG 5.

Regulation of fusion promotion by receptor binding protein. The cell-to-cell fusion of 293T cells coexpressing uncleaved influenza virus (HA), the indicated F proteins (x axis), and MeV H WT (A), MeV H SSPE (B), or the empty vector pCAGGS (C) was assessed by a β-Gal complementation assay using target cells that do not express MeV H receptor. The values are expressed as the mean RLU (with SEM) of results from three independent experiments in triplicate. ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed, unpaired t test).

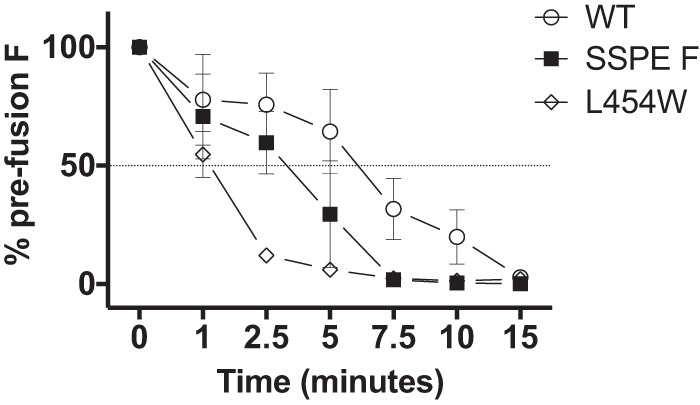

Both SSPE and MIBE F proteins show thermal instability.

As previously shown, decreased thermal stability of F correlates with enhanced fusogenicity (8, 21) and ease of activation to a triggered conformation. The thermal stability of SSPE F and MIBE F L454W were compared at various time points by incubating cells expressing the indicated F proteins at 55°C (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Significantly more prefusion epitopes were detected after 5 min at 55°C in cells expressing SSPE F than in cells expressing MIBE F L454W, suggesting that SSPE F is more stable than L454W F. Both mutant F proteins were less stable than wild-type B3 F, which maintained 70% prefusion epitope expression after 5 min. In Table 2, the F proteins bearing single mutations are compared to the three F proteins shown in Fig. 6.

FIG 6.

Thermal stability of the MeV wild-type and mutant F proteins. 293T cells expressing the indicated MeV F proteins (x axis) were incubated overnight at 37°C. The cells were then incubated for the indicated times at 55°C and then at 4°C with mouse MAbs recognizing the prefusion conformation of MeV F (21). The values on the y axis represent the percentages of conformational antibody binding and indicate the averages (with SEM) of results from four independent experiments in triplicate. WT, wild-type F; SSPE, F bearing G168R, E170G, S262G, A440P, R520C, and L550P. The L454W F (found in two MIBE clinical samples) (7) was added for comparison.

TABLE 2.

Thermal stability of the B3 F mutant proteins detected by binding of a MAb specific for the prefusion conformation of Fa

| F protein | TS50 | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 5 min 9 s | 3 min 52 s | 6 min 51 s |

| SSPE | 2 min 29 s | 1 min 47 s | 3 min 28 s |

| G168R | 4 min 24 s | 3 min 22 s | 5 min 45 s |

| E170G | 6 min 37 s | 5 min 13 s | 8 min 25 s |

| S262G | 3 min 10 s | 2 min 32 s | 3 min 59 s |

| A440P | 5 min 11 s | 3 min 37 s | 7 min 24 s |

| R520C | 5 min 54 s | 4 min 36 s | 7 min 33 s |

| L550P | 6 min 26 s | 5 min 27 s | 7 min 37 s |

| L454W | 1 min 5 s | 0 min 53 s | 1 min 19 s |

Data are reported as averages from four independent experiments and are expressed as the time (minutes) at 55°C that decreases the fraction of prefusion epitope to 50% (TS50) compared to that at time zero (100%; after overnight incubation at 37°C). WT, wild-type F; SSPE, MeV F bearing G168R, E170G, S262G, A440P, R520C, and L550P.

The data shown in Table 2 suggest that mutations at positions 168 and 262 reduce F stability, while the other mutations do not appear to individually affect stability. However, the SSPE substitutions in combination reduced thermal stability of the protein compared to that of wild-type F. For the hyperfusogenic MIBE F L454W, we confirmed that the single-amino-acid substitution was sufficient to decrease F stability (8).

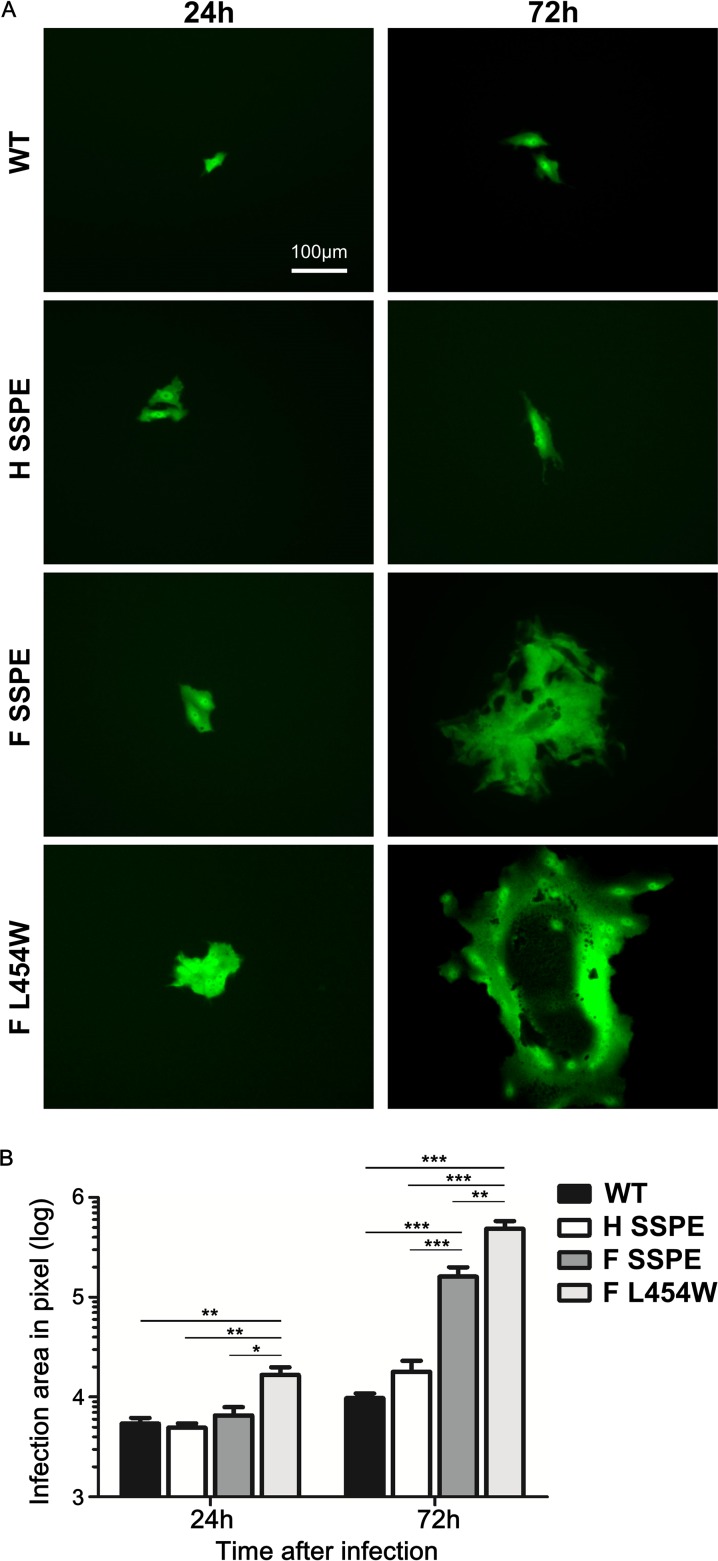

Recombinant viruses bearing CNS-adapted F proteins form syncytia in Vero cells.

Since the SSPE mutations in F conferred a hyperfusogenic phenotype of cell-to-cell fusion in the absence of known MeV receptors, we assessed the properties of the mutated glycoproteins in the context of infectious recombinant MeV IC323-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) viruses. In Fig. 7, recombinant MeV expressing wild-type F, MIBE F L454W, SSPE H, or SSPE F (with the long tail) and EGFP were used to infect Vero cells lacking known MeV receptors. Although all of the viruses were infectious, the wild-type B3 F and SSPE H recombinant viruses did not form syncytia (Fig. 7A). As previously shown, the hyperfusogenic MIBE F L454W induced syncytium formation after 24 h (8). The SSPE F recombinant virus formed less extensive syncytia and did so only after 72 h, suggesting that a less stable F allows MeV to spread from cell to cell in the absence of known MeV receptors, as observed for the MIBE F L454W mutant (8). Syncytium comparison demonstrated that MIBE F L454W mutant plaques were significantly larger than those of all other recombinant viruses 24 h postinfection (Fig. 7B). After 72 h, both MeV F L454W and MeV F SSPE mutants produced plaques significantly bigger than those of wild-type B3 F and SSPE H viruses. Thus, the accumulated mutations in SSPE F recombinant virus lead to a hyperfusogenic phenotype that is intermediate between wild-type B3 virus and the previously described MeV F L454W mutant virus.

FIG 7.

MeV recombinant viruses spread in the absence of known receptor. (A) Vero cells (without known MeV receptor) were infected with the indicated recombinant viruses expressing EGFP and incubated at 37°C. Infected cells were detected 24 and 72 h postinfection using an epifluorescence Nikon TS2R-FL inverted microscope. (B) Areas of infection, in pixels, were measured using ImageJ software on images randomly acquired from three separate experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; each by Mann-Whitney U test, n = 8 at least).

DISCUSSION

Measles infection at a young age is the greatest risk factor for SSPE (22). The child in this report had been vertically infected with HIV and acquired measles before 6 months of age. The maternal immunity status and level of maternal antibodies is unknown. HIV-related immune compromise and the young age of this patient could have contributed to poor immune function during acute infection, allowing for extensive virus replication and dissemination to the brain (23), despite SSPE (in contrast to MIBE) not generally being associated with immune defects. While the MeV in this child was not extensively mutated genome-wide, it showed characteristic SSPE genetic changes, including hypermutation at the N-P gene border and in the M and P genes, mutations and loss of the stop codon in F, and relative preservation of the N and L genes. Hypermutations were largely U to C, indicating that nucleotide modification was taking place mainly on the antisense (+) strand. The lower mutation burden in this virus than is typically found in SSPE may relate to the shorter-than-usual incubation period of 4 years. There were even fewer mutations in the related MIBE viruses, possibly reflecting the shorter incubation associated with this disorder (7).

Mutations that were present in the ectodomain of F in both SSPE and MIBE viruses conferred a hyperfusogenic phenotype, evident in two functional assays. First, fusion activity revealed that H/F pairs from MIBE and SSPE viruses mediated membrane fusion in the absence of the recognized MeV receptors, CD150 and nectin-4 (37–40). Second, the SSPE and MIBE F proteins lose the prefusion conformation more readily than the wild-type B3 F. By both measures, MIBE F L454W showed greater fusion activity than SSPE F. In the case of SSPE F, the increased fusion activity was due to a combination of mutations. When assessed, significant fusion activity in the absence of a known receptor(s) was observed only when all 6 mutations were present (Fig. 4). To assess cell-to-cell fusion, the extent of syncytium formation was also examined (data not shown). In this qualitative assay, the only amino acid substitution derived from the SSPE F that enhanced fusion on its own was S262G. This residue is located at the interface of three protomers, a region that is involved in fusion activation. A different substitution at residue 262 (S262R) has been reported previously and also confers a hyperfusogenic phenotype (6).

A hyperfusogenic phenotype is characteristic of MeV from brain tissue (4, 6, 24). While other genetic changes, including alterations to the F protein cytoplasmic tail or a nonfunctional M protein, have also been shown to enhance fusion in an animal model (25, 26), mutations in the F ectodomain alone also induce this phenotype. Recombinant viruses bearing F proteins with hyperfusogenic ectodomain substitutions spread efficiently in neurons but less so in cells expressing regular MeV receptors, possibly due to cytopathology (4, 5). In this study, Vero cells that did not express nectin-4 or CD150 were used to assess infection and spread of recombinant viruses bearing the F mutations found in MIBE and SSPE MeV. As previously shown, recombinant viruses expressing MIBE F L454W were infectious and caused large syncytium without engagement of known MeV receptors. The SSPE F recombinants were infectious as well, but cell-to-cell spread was slower than that for the MIBE recombinant, suggesting that the specific mutations in F were responsible. Thus, mutations in the ectodomain of F permit fusion without H engaging known MeV receptors; we suggest that these mutations promote infection of the brain. Our observations are supported by a recent finding by Sato et al. (4) where hyperfusogenic MeV bearing the T461I mutation in the F protein spread exclusively from cell to cell in terminally differentiated neuron cultures (4), without extracellular virus or budding. In contrast, wild-type MeV did not spread. Interestingly, however, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against H protein impaired the spread of hyperfusogenic viruses. Our findings support an ongoing role of H in SSPE. Indeed, although SSPE F could be activated independently of receptor engagement by H, activation was possible only when H was present. In contrast, F bearing the MIBE mutation L454W can mediate fusion in either the presence or absence of H (though at a lower level).

A notable clinical difference between MIBE and SSPE is that the former generally affects patients with defective cellular immunity. In MIBE there is little evidence of an antiviral immune response either peripherally or in the central nervous system, allowing MeV to spread in the brain more readily. In contrast, SSPE patients are generally immunocompetent, and high levels of anti-MeV antibodies are present in blood and CSF, with characteristic oligoclonal anti-MeV antibodies in the CNS. Most clones of these antibodies are directed to epitopes on the MeV N protein (the most abundant viral protein present in the brain) (27). Although only a few clones recognize other viral structural proteins, such as H and F, these antibodies would still be likely to bind to H and F proteins expressed on neurons and slow cell-to-cell spread. While the SSPE patient in our study was HIV infected, he had high levels of MeV antibodies in his CSF and his disease process ran a course typical of SSPE.

In this work, we limited our analysis to the MeV H and F proteins, and our findings are in line with evidence from our and other groups showing a direct correlation between the fusion phenotype described here (i.e., fusion in the absence of known receptor) and neuropathogenesis in vivo (4–6, 8, 11, 28). It remains unknown to what extent the other genetic alterations present in the SSPE viral sequence contribute to neuron invasion versus neurovirulence. To address this question, future work will assess the impact of each specific genetic change present in the SSPE MeV genome in vitro and in vivo. We propose that understanding the determinants for measles CNS infection and neurovirulence will shed light on longstanding questions about the mechanism of measles persistence and may guide antiviral approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MIBE and South African epidemic control samples.

Viral sequence data from patients acutely infected during the 2009-2010 epidemic and from the brains of patients with MIBE were compared. The GenBank accession numbers of MIBE and control virus sequences are KC305651 to KC305689. The clinical details of patients have been previously described (7).

PCR of MeV genes from postmortem brains.

Fresh brain tissue was collected and extracted using the manual Qiagen tissue protocol (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). cDNA synthesis and nested PCR of the N, M, F, and H genes were performed as previously described (7). The P genes of one SSPE and two MIBE viruses were amplified using previously described primers (29). The L gene of the SSPE virus was amplified using primers from Bankamp et al. (29).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Products were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA, USA) and PCR primers, except for the P and L, where M13 F (−20) and M13R (−26) primers were used. All six genes and intergenic regions were sequenced, except for the leader and trailer sequences. Sequences were assembled and aligned against a genotype B3 reference sequence (GenBank accession no. HM439386) using DNA Baser Sequence Assembler, v3.5.4 (Heracle BioSoft; www.DnaBaser.com). N and H genes were aligned with genotype B sequences from GenBank using BioEdit, and a maximum likelihood tree was constructed using Mega 6.06 and the Tamura Nei model with 1,000 bootstrap resamplings (30).

Consensus epidemic sequence.

A consensus sequence representing the 2009-2010 epidemic virus was determined by alignment of sequences from patients with acute measles. This was used to compare MIBE and SSPE brain virus sequences.

Structural modeling.

Twenty models of the wild-type measles virus fusion glycoprotein (MeV F) were generated using the protein homology server Phyre2 (31). The model was built from the crystal structure of MeV fusion glycoprotein in its prefusion state (PDB entry 5YXW) (16).

Cell cultures.

HEK-293T (human kidney epithelial) and Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Plasmids.

The genes of MeV B3 and IC323 F and H proteins, and nectin-4 and CD150, were codon optimized, synthesized, and subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCAGGS by Epoch Biolabs (Missouri City, TX).

Transient expression of viral glycoproteins.

Transfections were performed in HEK-293T cells according to the protocols of the Lipofectamine 2000 manufacturer (Invitrogen). Alternatively, cells were transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI; Polysciences, Inc.) (32). Briefly, DNA constructs, dissolved in Opti-MEM (Thermo Scientific), were mixed with PEI (1:2.5 ratio), incubated for 20 min at room temperature, and then added to the cells. After 4 h, the transfection mix was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics.

β-Gal complementation-based fusion assay.

To quantify cell-to-cell fusion, we used a fusion assay based on alpha-omega complementation of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) that was previously described (33, 34). Briefly, 293T cells transiently transfected with the omega reporter subunit and the receptor plasmids were incubated with cells coexpressing viral glycoproteins and the alpha reporter subunit (35). Cell fusion, which leads to β-Gal complementation, was stopped by lysing cells, and the luminescence obtained by adding the Galacton-Star substrate (Applied Biosystems) was measured on an Infinite M1000PRO (Tecan) microplate reader.

β-Gal assay for cell immunity staining with F-conformation-specific MAbs.

293T cells transiently transfected with viral glycoprotein constructs were incubated overnight at 32°C in complete medium (DMEM, 10% FBS) and processed as previously described (8). Briefly, 20 h posttransfection, cells were transferred to the temperatures and times indicated in the figures. Thereafter, cells were incubated with mouse MAbs that specifically detect MeV F in its prefusion conformation (1:1,000) for 1 h on ice. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated for 1 h on ice with biotin-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500; Life Technologies). Cells were washed with PBS and then fixed for 10 min on ice with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Cells were then washed twice with PBS, blocked for 20 min on ice with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, washed, and then incubated for 1 h on ice with streptavidin conjugated with β-galactosidase (1:1,000; Life Technologies). Cells were washed with PBS, β-galactosidase substrate (1:50; Applied Biosystems) was added, and luminescence was measured by an Infinite M1000PRO (Tecan) microplate reader.

Cell surface expression.

Cells expressing glycoproteins were incubated for 1 h with cycloheximide to synchronize protein expression and treated with 2.5 mg/ml of NHS-S-S-dPEG4-biotin (Quanta Biodesign) in PBS for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed with Dulbecco’s PBS and lysed with DH buffer (50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.005 g/ml dodecyl maltoside) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and clarified by centrifugation. Samples were then incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotary wheel with streptavidin-agarose (Thermo Scientific). The next day, samples were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min and the pellet (biotinylated proteins) washed and processed for Western blot analysis.

Recombinant virus production and analysis.

MeV IC323-EGFP is a recombinant virus expressing the EGFP gene. All variant mutations, including F L454W, F SSPE, and H SSPE, were engineered in the MeV IC323-EGFP background using reverse genetics. MeV IC323 recombinant viruses were rescued in 293-3-46 cells as previously described (36). MeV recombinants were titrated by plaque assay on Vero/human SLAM cells. In the experiment to assess spread of virus, Vero cells (without known MeV receptor) were infected (multiplicity of infection of 0.03) with the indicated recombinant viruses expressing EGFP and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The media were replaced with DMEM–10% FBS, and infected cells were incubated again for up to 72 h at 37°C. Micrographs were obtained using an epifluorescence Nikon TS2R-FL inverted microscope. Areas of infection in pixels were measured using ImageJ software on images randomly acquired from three separate experiments (n = 8 minimum).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) software. All data were expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from at least three independent experiments in triplicate and analyzed by the unpaired Student's t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA), and post hoc test when required, or by Mann-Whitney U test. Data were considered significant at a P value of <0.05.

Ethical approval.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC REF 163/2011).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by NIH grants NS091263 and NS105699 to M.P.; French ANR NITRODEP (ANR-13-PDOC-0010-01) to C.M.; Region Auvergne Rhone Alpes and LABEX ECOFECT (ANR-11-LABX-0048) of Lyon University, “Investissements d'Avenir” (ANR-11-IDEX-0007)/French National Research Agency (ANR), to B.H.; and Japan AMED J-PRIDE (JP18fm0208022h).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01700-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ntshoe GM, McAnerney JM, Archer BN, Smit SB, Harris BN, Tempia S, Mashele M, Singh B, Thomas J, Cengimbo A, Blumberg LH, Puren A, Moyes J, van den Heever J, Schoub BD, Cohen C. 2013. Measles outbreak in South Africa: epidemiology of laboratory-confirmed measles cases and assessment of intervention, 2009-2011. PLoS One 8:e55682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertyn C, van der Plas H, Hardie D, Candy S, Tomoka T, Leepan EB, Heckmann JM. 2011. Silent casualties from the measles outbreak in South Africa. S Afr Med J 101:313–314. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kija E, Ndondo A, Spittal G, Hardie DR, Eley B, Wilmshurst JM. 2015. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in South African children following the measles outbreak between 2009 and 2011. S Afr Med J 105:713–718. doi: 10.7196/SAMJnew.7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato Y, Watanabe S, Fukuda Y, Hashiguchi T, Yanagi Y, Ohno S. 2018. Cell-to-cell measles virus spread between human neurons is dependent on hemagglutinin and hyperfusogenic fusion protein. J Virol 92:e02166-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02166-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe S, Ohno S, Shirogane Y, Suzuki SO, Koga R, Yanagi Y. 2015. Measles virus mutants possessing the fusion protein with enhanced fusion activity spread effectively in neuronal cells, but not in other cells, without causing strong cytopathology. J Virol 89:2710–2717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03346-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe S, Shirogane Y, Suzuki SO, Ikegame S, Koga R, Yanagi Y. 2013. Mutant fusion proteins with enhanced fusion activity promote measles virus spread in human neuronal cells and brains of suckling hamsters. J Virol 87:2648–2659. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02632-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardie DR, Albertyn C, Heckmann JM, Smuts HE. 2013. Molecular characterisation of virus in the brains of patients with measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE). Virol J 10:283. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jurgens EM, Mathieu C, Palermo LM, Hardie D, Horvat B, Moscona A, Porotto M. 2015. Measles fusion machinery is dysregulated in neuropathogenic variants. mBio 6:e02528-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02528-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattaneo R, Schmid A, Eschle D, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Billeter MA. 1988. Biased hypermutation and other genetic changes in defective measles viruses in human brain infections. Cell 55:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90048-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rima BK, Duprex WP. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of measles virus persistence. Virus Res 111:132–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid A, Spielhofer P, Cattaneo R, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Billeter MA. 1992. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis is typically characterized by alterations in the fusion protein cytoplasmic domain of the persisting measles virus. Virology 188:910–915. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90552-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayata M, Komase K, Shingai M, Matsunaga I, Katayama Y, Ogura H. 2002. Mutations affecting transcriptional termination in the p gene end of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis viruses. J Virol 76:13062–13068. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13062-13068.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cattaneo R, Rebmann G, Schmid A, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Billeter MA. 1987. Altered transcription of a defective measles virus genome derived from a diseased human brain. EMBO J 6:681–688. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattaneo R, Schmid A, Rebmann G, Baczko K, Ter Meulen V, Bellini WJ, Rozenblatt S, Billeter MA. 1986. Accumulated measles virus mutations in a case of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: interrupted matrix protein reading frame and transcription alteration. Virology 154:97–107. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson JB, Cornu TI, Redwine J, Dales S, Lewicki H, Holz A, Thomas D, Billeter MA, Oldstone MB. 2001. Evidence that the hypermutated M protein of a subacute sclerosing panencephalitis measles virus actively contributes to the chronic progressive CNS disease. Virology 291:215–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashiguchi T, Fukuda Y, Matsuoka R, Kuroda D, Kubota M, Shirogane Y, Watanabe S, Tsumoto K, Kohda D, Plemper RK, Yanagi Y. 2018. Structures of the prefusion form of measles virus fusion protein in complex with inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:2496–2501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718957115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mateo M, Navaratnarajah CK, Cattaneo R. 2014. Structural basis of efficient contagion: measles variations on a theme by parainfluenza viruses. Curr Opin Virol 5:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porotto M, Palmer SG, Palermo LM, Moscona A. 2012. Mechanism of fusion triggering by human parainfluenza virus type III: communication between viral glycoproteins during entry. J Biol Chem 287:778–793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porotto M, Salah ZW, Gui L, DeVito I, Jurgens EM, Lu H, Yokoyama CC, Palermo LM, Lee KK, Moscona A. 2012. Regulation of paramyxovirus fusion activation: the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein stabilizes the fusion protein in a pretriggered state. J Virol 86:12838–12848. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01965-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell CJ, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA. 2001. Membrane fusion machines of paramyxoviruses: capture of intermediates of fusion. EMBO J 20:4024–4034. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ader N, Brindley M, Avila M, Orvell C, Horvat B, Hiltensperger G, Schneider-Schaulies J, Vandevelde M, Zurbriggen A, Plemper RK, Plattet P. 2013. Mechanism for active membrane fusion triggering by morbillivirus attachment protein. J Virol 87:314–326. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01826-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin DE, Lin WH, Pan CH. 2012. Measles virus, immune control, and persistence. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:649–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McQuaid S, Cosby SL, Koffi K, Honde M, Kirk J, Lucas SB. 1998. Distribution of measles virus in the central nervous system of HIV-seropositive children. Acta Neuropathol 96:637–642. doi: 10.1007/s004010050945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayata M, Shingai M, Ning X, Matsumoto M, Seya T, Otani S, Seto T, Ohgimoto S, Ogura H. 2007. Effect of the alterations in the fusion protein of measles virus isolated from brains of patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis on syncytium formation. Virus Res 130:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cathomen T, Mrkic B, Spehner D, Drillien R, Naef R, Pavlovic J, Aguzzi A, Billeter MA, Cattaneo R. 1998. A matrix-less measles virus is infectious and elicits extensive cell fusion: consequences for propagation in the brain. EMBO J 17:3899–3908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cathomen T, Naim HY, Cattaneo R. 1998. Measles viruses with altered envelope protein cytoplasmic tails gain cell fusion competence. J Virol 72:1224–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgoon MP, Owens GP, Carlson S, Maybach AL, Gilden DH. 2001. Antigen discovery in chronic human inflammatory central nervous system disease: panning phage-displayed antigen libraries identifies the targets of central nervous system-derived IgG in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Immunol 167:6009–6014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.6009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayata M, Takeuchi K, Takeda M, Ohgimoto S, Kato S, Sharma LB, Tanaka M, Kuwamura M, Ishida H, Ogura H. 2010. The F gene of the Osaka-2 strain of measles virus derived from a case of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis is a major determinant of neurovirulence. J Virol 84:11189–11199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01075-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bankamp B, Liu C, Rivailler P, Bera J, Shrivastava S, Kirkness EF, Bellini WJ, Rota PA. 2014. Wild-type measles viruses with non-standard genome lengths. PLoS One 9:e95470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirschner M, Monrose V, Paluch M, Techodamrongsin N, Rethwilm A, Moore JP. 2006. The production of cleaved, trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein vaccine antigens and infectious pseudoviruses using linear polyethylenimine as a transfection reagent. Protein Expr Purif 48:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moosmann P, Rusconi S. 1996. Alpha complementation of LacZ in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 24:1171–1172. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.6.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porotto M, Carta P, Deng Y, Kellogg GE, Whitt M, Lu M, Mungall BA, Moscona A. 2007. Molecular determinants of antiviral potency of paramyxovirus entry inhibitors. J Virol 81:10567–10574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01181-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porotto M, Rockx B, Yokoyama CC, Talekar A, Devito I, Palermo LM, Liu J, Cortese R, Lu M, Feldmann H, Pessi A, Moscona A. 2010. Inhibition of Nipah virus infection in vivo: targeting an early stage of paramyxovirus fusion activation during viral entry. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001168. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathieu C, Huey D, Jurgens E, Welsch JC, DeVito I, Talekar A, Horvat B, Niewiesk S, Moscona A, Porotto M. 2015. Prevention of measles virus infection by intranasal delivery of fusion inhibitor peptides. J Virol 89:1143–1155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02417-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashiguchi T, Ose T, Kubota M, Maita N, Kamishikiryo J, Maenaka K, Yanagi Y. 2011. Structure of the measles virus hemagglutinin bound to its cellular receptor SLAM. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mateo M, Navaratnarajah CK, Syed S, Cattaneo R. 2013. The measles virus hemagglutinin beta-propeller head beta4-beta5 hydrophobic groove governs functional interactions with nectin-4 and CD46 but not those with the signaling lymphocytic activation molecule. J Virol 87:9208–9216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01210-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muhlebach MD, Mateo M, Sinn PL, Prufer S, Uhlig KM, Leonard VH, Navaratnarajah CK, Frenzke M, Wong XX, Sawatsky B, Ramachandran S, McCray PB Jr, Cichutek K, von Messling V, Lopez M, Cattaneo R. 2011. Adherens junction protein nectin-4 is the epithelial receptor for measles virus. Nature 480:530–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noyce RS, Bondre DG, Ha MN, Lin LT, Sisson G, Tsao MS, Richardson CD. 2011. Tumor cell marker PVRL4 (nectin 4) is an epithelial cell receptor for measles virus. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002240. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.