Abstract

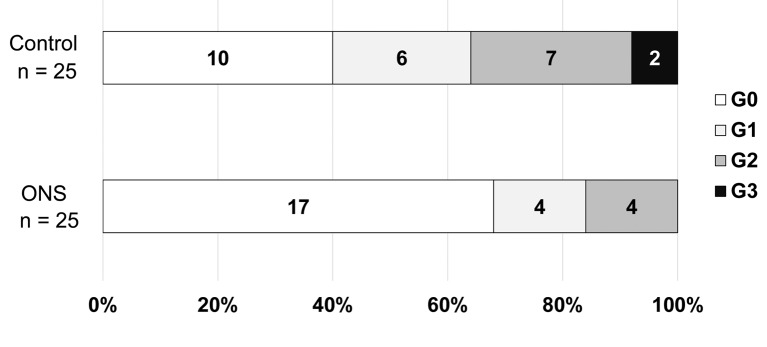

Background/Aim: Sorafenib is standard treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) is a notorious side-effect of this therapy. This study evaluated prophylactic benefits of an oral nutritional supplement (ONS) on sorafenib-associated HFSR in advanced HCC. Patients and Methods: This was a prospective, single-center, open-label trial arm using combined ONS and sorafenib in patients with unresectable HCC from August 2014 to February 2018. Control patients received sorafenib without ONS from 2011 to 2014. From September 2014, prophylactic ONS containing β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB), L-arginine, and L-glutamine was given. Sorafenib dosage was 400 mg/day for both groups. Results: Each group comprised 22 men and three women. Age, sex, Child-Pugh score, and clinical stage excluding IV-B did not significantly differ between the groups. HFSR occurred after 2 weeks: 15/25 patients in the control group (60%; HFSR grade 1: 6, grade 2: 7, grade 3: 2) vs. 8/25 in the ONS group (32%; HFSR grade 1: 4, grade 2: 4, grade 3: 0; p=0.047, Pearson’s Chi-square test). Conclusion: Prophylactic HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine supplementation effectively prevented sorafenib-associated HFSR in patients with advanced HCC.

Keywords: Sorafenib, hand–foot skin reaction, β-hydroxy-β-methyl butyrate acid, L-arginine, L-glutamine

Sorafenib, an oral inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinase receptors, is a standard treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) is a common side-effect that sometimes causes discontinuation of sorafenib treatment. It is therefore vital to manage HFSR in order to allow continuation of sorafenib. The incidence of HFSR (any grade) in the sorafenib arms of HCC clinical trials is in the range of 21.2-45% (1). Prevention of HFSR is particularly important in Japanese patients with HCC because HFSR tends to develop frequently in Asian populations compared with Western populations (2,3). In addition to patient education about signs and symptoms of HFSR, skin hydration with topical urea-based creams is considered the most important primary proactive management (1). Despite such preventive treatment, HFSR still occurs, making it difficult for patients to continue sorafenib.

Recently, an oral nutritional supplement (ONS) containing β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB), L-arginine, and L-glutamine was reported to be effective against capecitabine-induced HFSR (4). The present study was designed to evaluate the preventive effect of an ONS comprising HMB, L-arginine, and L-glutamine on sorafenib-associated HFSR in patients with advanced HCC.

Patients and Methods

Study design. This study compared data obtained in a prospective study with data obtained from historical controls. The prospective, single-center, open-label trial arm using combined ONS and sorafenib involved patients diagnosed with unresectable HCC according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Criteria (or the Japan Liver Cancer Study Group Criteria) from August 2014 to February 2018 (5,6). Patients treated with sorafenib without ONS from January 2011 to July 2014 were enrolled as historical controls and clinical information was collected retrospectively from their electronic medical records. The primary endpoint was incidence of any grade HFSR within 12 weeks of starting sorafenib. Secondary endpoints included time to first occurrence of HFSR, duration of HFSR, percentage of patients with sorafenib dose reduction and interruption or discontinuation, tumor response according to modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) criteria (7), overall survival (OS), ONS toxicity, and ONS adherence. The HFSR evaluable population comprised all patients who received at least one dose of sorafenib. The efficacy population comprised all patients who received at least one dose of sorafenib and had computed tomographic (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) available for tumor assessment.

This study was registered in the Clinical Trials Registry of the Japan National University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) on August 27, 2014 (registration ID: UMIN000014953).

Eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥20 years; HCC diagnosed histologically or clinically (e.g. angiography, CT, and MRI); no indications for hepatectomy or percutaneous radiofrequency ablation; Child–Pugh class A or B; clinical stage II, III, or IV; sufficient organ function; a white blood cell count of ≥3000 cells/μI; platelet count of ≥5.0×104/μl; serum total bilirubin <3.0 mg/dl; and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2. Clinical staging of HCC was determined using the Japanese Liver Cancer Study Group (JLCSG) system (5). Exclusion criteria were renal failure (estimated glomerular filtration rate <15 ml/min/1.73 m2 or requiring dialysis), previous myocardial infarction or arrhythmia requiring treatment, active concomitant advanced cancer, and refractory ascites or pleural effusion.

Efficacy and safety evaluation. HFSR and all other adverse events (AEs) were evaluated by the treating physician and expert nurse using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4 (CTCAE v4.0) (8). HFSR was graded as follows: grade 1 (mild): minimal skin changes or dermatitis (erythema) without pain; grade 2 (moderate): skin changes (peeling, blisters, bleeding, edema) or pain, not interfering with function; and grade 3 (severe): ulcerative dermatitis or skin changes with pain interfering with function. Patients in the ONS group were examined for AEs commonly associated with sorafenib treatment every 2 weeks up to 12 weeks. ONS adherence was also checked at every hospital visit.

Response to sorafenib treatment was evaluated using the mRECIST guidelines (7). Clinical images were obtained using dynamic CT or MRI every 2 months in general. OS was calculated as the period from the date that sorafenib therapy was initiated to the date of death, or until May 2018 for surviving patients.

Treatment method. Clinical indications for HCC treatment using sorafenib were based on the 2013 Clinical Practice Guidelines for HCC of the Japan Society of Hepatology (9). Sorafenib was started for advanced HCC in our hospital in 2009. Because serious AEs were encountered, such as hepatic coma or highly elevated alanine aminotransferase level, upon starting sorafenib therapy (800 mg/day), the initial sorafenib dose was unified to 400 mg/day in patients with HCC. Once HFS management had been mastered, from 2011 to 2014 the control group included patients treated with sorafenib but who did not receive ONS. In September 2014, the administration of orange-flavored prophylactic ONS, Abound™ (Abbott Nutrition, Lake Forest, IL, USA), to sorafenib-treated patients was started. One pack of Abound™ contains HMB (1.2 g/pack), L-arginine, (7 g/pack), and L-glutamine (7 g/pack), and 79 kcal per 24 g. Abound™ was purchased with our hospital’s research funding. In general, patients took one pack of Abound™ daily for >3 months. Nutritional guidance was given by registered dietitians to all patients with HCC in order to maintain a good general condition, with reference to the 2012 guidelines of the Japanese Nutritional Study Group for Liver Cirrhosis (10).

All patients received the following basic treatment to prevent HFSR. Prior to sorafenib treatment, patient education (review of HFSR signs and symptoms, including onset and duration) was provided by our healthcare team comprising a trained doctor, nurse, and pharmacist. All patients and their relatives were required to record signs and symptoms daily, and the value and importance of daily skin care to patients was emphasized. All patients were taught daily skin care, which involved the application of 10% urea-based cream three times daily on the hands and feet to soften hyperkeratosis and reduce epidermal thickness. For ongoing patient education, the daily skin care regimen was reinforced and regular scheduled follow-up conducted to assess the skin, particularly in the first 2 weeks to 3 months of sorafenib treatment. Living habits were also guided by requiring patients to wear thick cotton socks and comfortable supportive shoes to protect the feet, cotton gloves to protect the hands and rubber gloves when washing dishes, and to avoid hot water. When grade 1 HFSR occurred, patients were followed-up at least every 2 weeks and a strong steroid (0.05% difluprednate) was used for the affected areas. Changes in the dosing of sorafenib were did not recommend. When grade 2 HFSR occurred, anti-inflammatory agents were used (e.g. 60 mg loxoprofen every 8 h, with food) for symptomatic relief. The goal was to bring HFSR to grade 0 or 1 toxicity. Dose reduction of sorafenib to 200 mg daily was recommended until HFSR resolved. If toxicity did not resolve to grade 0 or 1 HFSR, sorafenib was interrupted until HFSR had resolved. When grade 3 HFSR occurred, sorafenib was interrupted until HFSR had resolved. After resuming sorafenib at a reduced dose (200 mg), the dose was increased to 400 mg if HFSR remained at grade 0 or 1.

Statistical analysis. Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean of each variable between the two groups. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the median of each variable. Categorical data were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Survival was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method, with differences examined using the log-rank test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

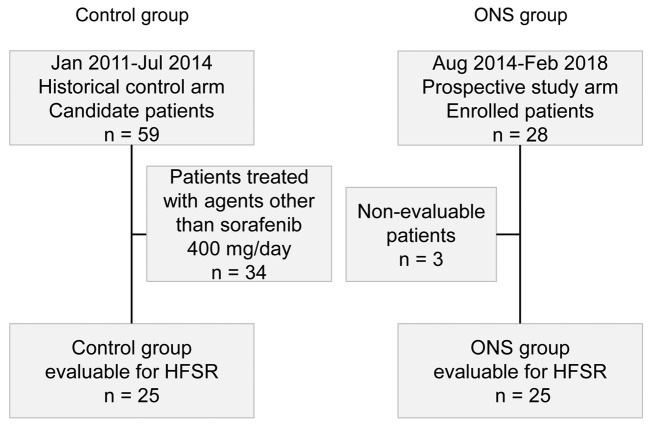

Patient characteristics. In total, 59 patients with HCC were treated using sorafenib at our hospital from January 2011 to July 2014; these were candidate patients from the historical control arm. After excluding 34 patients on doses other than 400 mg/day sorafenib, 25 patients were enrolled in the control group. Between August 2014 and February 2018, 28 patients with HCC were enrolled in the prospective study arm. It was not possible to evaluate three of these patients because they were lost to follow-up, leaving 25 patients for analysis in the ONS group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design. HFSR: Hand–foot skin reaction; ONS: oral nutritional supplement.

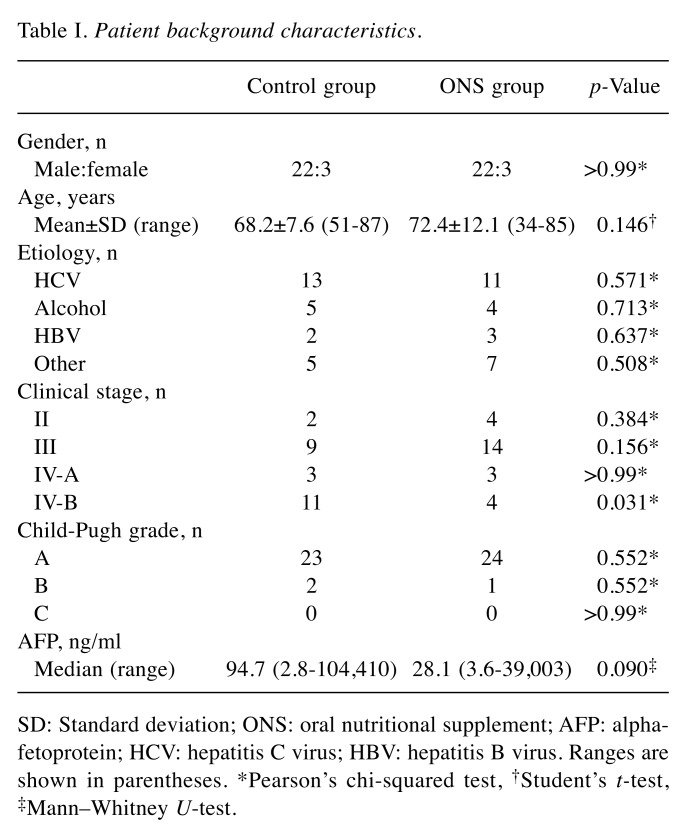

The control group and ONS group each comprised 22 men and three women. Table I shows a comparison of the background characteristics between the two groups. Neither group showed significant differences in terms of sex, age, etiology, clinical stage excluding IV-B using the Japanese Liver Cancer Study Group classification system, Child-Pugh score, or alpha-fetoprotein level. All patients with HCC started sorafenib treatment at 400 mg/day.

Table I. Patient background characteristics.

SD: Standard deviation; ONS: oral nutritional supplement; AFP: alphafetoprotein; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus. Ranges are shown in parentheses. *Pearson’s chi-squared test, †Student’s t-test, ‡Mann–Whitney U-test.

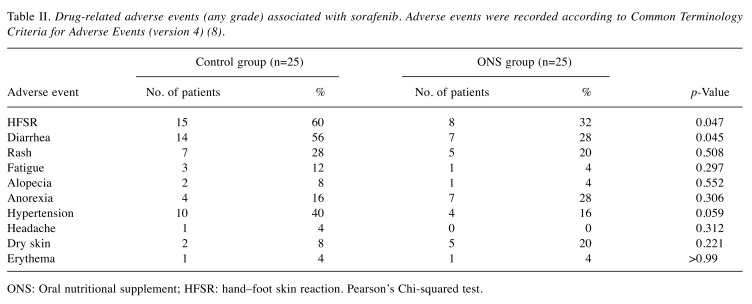

Evaluation of HFSR and other adverse effects. Table II shows the occurrence of sorafenib-associated AEs of any grade. The control group had significantly more cases of HFSR than the ONS group [n=15 (60%) vs. n=8 (32%), respectively; p=0.047] as well as significantly more cases of diarrhea [n=14 (56%) vs. n=7 (28%), respectively; p=0.045]. There were no significant between-group differences in the occurrence of rash, fatigue, alopecia, anorexia, hypertension, headache, dry skin, or erythema.

Table II. Drug-related adverse events (any grade) associated with sorafenib. Adverse events were recorded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4) (8).

ONS: Oral nutritional supplement; HFSR: hand–foot skin reaction. Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

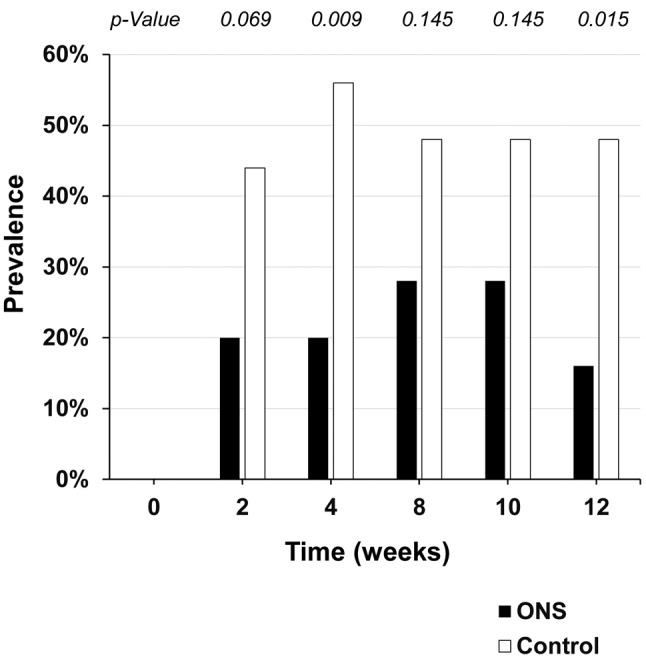

Figure 2 shows the HFSR grades in the control and ONS groups. HFSR developed in 15 out of 25 patients in the control group but in eight out of 25 patients in the ONS group (p=0.047). Figure 3 shows the prevalence rates of HFSR of any grade at each visit. HFSR occurred after about 2 weeks in both groups, with a significant difference in HFSR prevalence after 4 weeks (p=0.009). Prevalence was lower in the ONS group than the control group at all visits.

Figure 2. Grades of hand–foot skin reaction. Statistical analysis was conducted using Pearson’s Chi-squared test, p=0.047.

Figure 3. Prevalence of any-grade hand–foot skin reaction at each study visit. Statistical analysis was conducted using Pearson’s Chi-squared test. ONS: Oral nutritional supplement.

Over the study period, 12 out of 25 patients in the control group required dose reduction (n=3) or discontinuation (n=9) of sorafenib due to AEs, with discontinuation required because of disease progression in another 13 patients; only one patient discontinued sorafenib due to HFSR. In the ONS group, 14 out of 25 patients required dose reduction (n=5) or discontinuation (n=9) of sorafenib due to AEs, with discontinuation needed in another 11 patients due to disease progression; two patients discontinued sorafenib due to HFSR.

ONS adherence was good by most patients, except for one who was only able to take half the pack due to the unpleasant taste. No other side-effects due to ONS were noted.

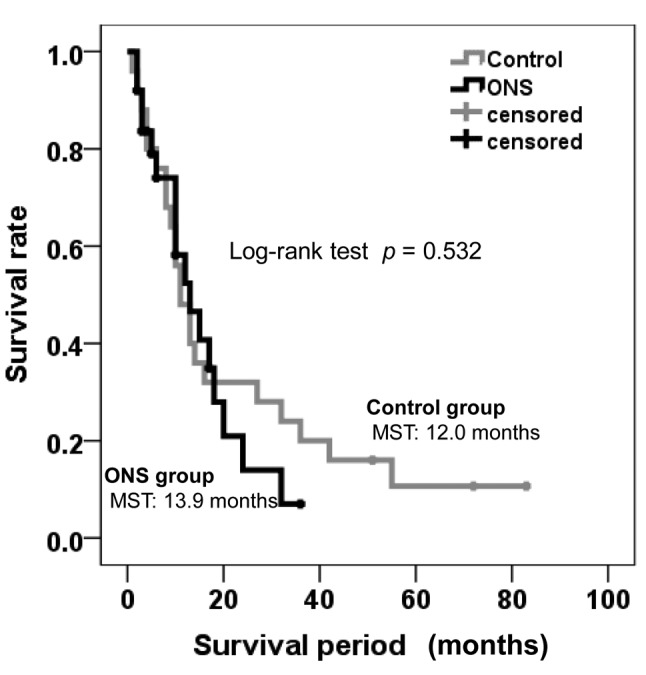

Responses to and outcomes of sorafenib treatment. The overall response rate was 8% (2/25) in both groups. Disease control rates were 56% (14/25) and 60% (15/25) in the control and ONS groups, respectively (p=0.775). Median survival time (MST) did not differ significantly between the groups (p=0.532; Figure 4). In the control group, 22 out of the 25 patients died of tumor progression and hepatic failure, and MST was 12.0 months, with 1-and 2-year survival rates of 48% and 32%, respectively. In the ONS group, 17 out of the 25 patients died of tumor progression and hepatic failure, and MST was 13.9 months, with 1-, and 2-year survival rates of 52.4% and 14%, respectively.

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier survival curve according to patient group. ONS, Oral nutritional supplement. MST: median survival time.

Discussion

HFSR is a very common side-effect in patients treated with sorafenib and affects the treatment schedule and quality of life (1). Successful management of HFSR depends on a strong partnership between the multidisciplinary healthcare team and the patient. Prompt intervention is advised in HFSR because early symptoms can be resolved quickly with minimum effort (11). Ren et al. (12) reported a phase II study that described the prophylactic effect of urea-based cream on HFSR in HCC and the reduced severity of HFSR through basic support (patient education, proactive management, and early detection). However, no standard of care has yet been adopted in patients with HCC treated using sorafenib.

For prevention of HFSR, in this study we focused on HMB L-arginine and L-glutamine as nutritional components that promote collagen synthesis (13). HMB is a naturally-occurring metabolite of the essential amino acid leucine. Several recent studies have hypothesized that HMB is the bioactive metabolite of leucine, responsible for inhibiting muscle proteolysis and modulating protein turnover in vitro and in vivo (14,15). HMB has been reported to promote protein synthesis via the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway involved in cell division and growth (16), to suppress degradation of body proteins by suppressing the ubiquitin-proteasome system, an intracellular protein degradation pathway (17), and to regulate excessive inflammatory response (18). L-Arginine, and L-glutamine are necessary for wound healing and serve to promote collagen synthesis (13). L-Arginine is a dietary semi-essential amino acid that becomes conditionally indispensable during critical illness and severe trauma (19). Dietary L-arginine supplementation, above the amounts required for optimal growth, nitrogen balance, or health, increases wound collagen accumulation in healthy humans (20). In a clinical report on cancer treatment, supplementation with HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine was potentially effective in the prevention of radiation dermatitis in patients with head and neck cancer (21). Matsuhashi et al. reported that such supplementation was apparently effective in the treatment of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody-associated skin disorder (22). Yokota et al. conducted a phase II study that showed the efficacy of HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine supplementation for chemoradiotherapy-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer (23). These findings would suggest a preventive effect of HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine against HFSR in patients with HCC treated with sorafenib. However, the molecular mechanisms accounting for sorafenib-induced HFSR in these patients remain to be elucidated.

Analysis of sorafenib-associated AEs showed a significant prevention of HFSR in the ONS group compared to the control group in the present study. Interestingly, diarrhea was also significantly reduced in the ONS group (Table II). Several reports have shown that glutamine can contribute to improving the toxic effects of chemotherapy, such as diarrhea, constipation, and nausea (24,25), and therefore it seems reasonable that HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine supplementation can also be preventive against sorafenib-induced diarrhea.

Wang et al. described HFSR as a useful indicator in patients with HCC receiving sorafenib therapy (26). In our study, an inhibitory effect of HFSR was obtained in the ONS group. However, there was no difference in OS between the ONS and control groups (Figure 4). Although details underlying this phenomenon are unknown, ONS may be useful in preventing negative effects on OS.

This study is limited by the fact that it involved historical controls. It is possible that AEs may have been missed in this control group if descriptions in the medical charts were inadequate. Accurate evaluation of the benefit of HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine supplementation against HFSR will require a double-blind randomized controlled trial involving a larger number of patients.

In conclusion, prophylactic supplementation with HMB, L-arginine and L-glutamine was effective in preventing sorafenib-associated HFSR in advanced HCC when combined with basic treatment and patient education about HFSR. However, no survival benefit was observed in patients receiving such supplementation. Randomized controlled trials will be necessary for accurate evaluation of such supplementation against HFSR.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent from the control group patients was waived because clinical information obtained in routine clinical practice was used. Written informed consent was obtained from the ONS group patients in this study. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Takasaki General Medical Center.

Disclosure Statement

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in regard to this study.

Funding Sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Mrs. Hideyo Mashimo and Mrs. Noriko Ozawa for their excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Walko CM, Grande C. Management of common adverse events in patients treated with sorafenib: Nurse and pharmacist perspective. Semin Oncol. 2014;41(Suppl2):S17–S28. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Haussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang H, Liu J, Wang J, Tak WY, Pan H, Burock K, Zou J, Voliotis D, Guan Z. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujii C, Imamura H, Fukunaga M, Kamigaki S, Kimura Y, Kawase T, Kawabata R, Fujino M, Iseki C, Hamaguchi Y, Yamamoto E, Ishizaka T, Hachino Y. Efficacy of AboundTM for hand–foot syndrome caused by capecitabine. Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. 2013;40(12):2457–2459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izumi N. Diagnostic and treatment algorithm of the Japanese Society of Hepatology: A consensus-based practice guideline. Oncology. 2010;78(Suppl1):78–86. doi: 10.1159/000315234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forner A, Reig ME, de Lope CR, Bruix J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: the BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):61–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institutes of Health , National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 2018 http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm (Last accessed October 6, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Japan Society of Hepatology Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma 2013. Tokyo, Japan, Japan Society of Hepatology. 2013 https://www.jsh.or.jp/English/guidelines_en/Guidelines_for_hepatocellular_carcinoma_2013 (Last accessed October 6, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki K, Endo R, Kohgo Y, Ohtake T, Ueno Y, Kato A, Suzuki K, Shiraki R, Moriwaki H, Habu D, Saito M, Nishiguchi S, Katayama K, Sakaida I. Guidelines on nutritional management in Japanese patients with liver cirrhosis from the perspective of preventing hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2012;42(7):621–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacouture ME, Wu S, Robert C, Atkins MB, Kong HH, Guitart J, Garbe C, Hauschild A, Puzanov I, Alexandrescu DT, Anderson RT, Wood L, Dutcher JP. Evolving strategies for the management of hand–foot skin reaction associated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Oncologist. 2008;13(9):1001–1011. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren Z, Zhu K, Kang H, Lu M, Qu Z, Lu L, Song T, Zhou W, Wang H, Yang W, Wang X, Yang Y, Shi L, Bai Y, Guo X, Ye SL. Randomized controlled trial of the prophylactic effect of urea-based cream on sorafenib-associated hand–foot skin reactions in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):894–900. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams JZ, Abumrad N, Barbul A. Effect of a specialized amino acid mixture on human collagen deposition. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):369–375. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papet I, Ostaszewski P, Glomot F, Obled C, Faure M, Bayle G, Nissen S, Arnal M, Grizard J. The effect of a high dose of 3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyrate on protein metabolism in growing lambs. Br J Nutr. 1997;77(6):885–896. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holecek M, Muthny T, Kovarik M, Sispera L. Effect of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) on protein metabolism in whole body and in selected tissues. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47(1):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eley HL, Russell ST, Baxter JH, Mukerji P, Tisdale MJ. Signaling pathways initiated by beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate to attenuate the depression of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle in response to cachectic stimuli. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(4):E923–E931. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00314.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith HJ, Mukerji P, Tisdale MJ. Attenuation of proteasome-induced proteolysis in skeletal muscle by {beta}-hydroxy-{beta}-methylbutyrate in cancer-induced muscle loss. Cancer Res. 2005;65(1):277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh LC, Chien SL, Huang MS, Tseng HF, Chang CK. Anti-inflammatory and anticatabolic effects of short-term beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in intensive care unit. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seifter E, Rettura G, Barbul A, Levenson SM. Arginine: an essential amino acid for injured rats. Surgery. 1978;84(2):224–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbul A, Lazarou SA, Efron DT, Wasserkrug HL, Efron G. Arginine enhances wound healing and lymphocyte immune responses in humans. Surgery. 1990;108(2):331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai T, Matsuura K, Asada Y, Sagai S, Katagiri K, Ishida E, Saito D, Sadayasu R, Wada H, Saijo S. Effect of HMB/Arg/Gln on the prevention of radiation dermatitis in head and neck cancer patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(5):422–427. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuhashi N, Takahashi T, Nonaka K, Ichikawa K, Yawata K, Tanahashi T, Imai H, Sasaki Y, Tanaka Y, Okumura N, Yamaguchi K, Osada S, Yoshida K. A case report on efficacy of Abound for anti-EGFR antibody-associated skin disorder in metastatic colon cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokota T, Hamauchi S, Yoshida Y, Yurikusa T, Suzuki M, Yamashita A, Ogawa H, Onoe T, Mori K, Onitsuka T. A phase II study of HMB/Arg/Gln against oral mucositis induced by chemoradiotherapy for patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(9):3241–3248. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serna-Thome G, Castro-Eguiluz D, Fuchs-Tarlovsky V, Sanchez-Lopez M, Delgado-Olivares L, Coronel-Martinez J, Molina-Trinidad EM, de la Torre M, Cetina-Perez L. Use of functional foods and oral supplements as adjuvants in Cancer Treatment. Rev Invest Clin. 2018;70(3):136–146. doi: 10.24875/RIC.18002527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolfaie NR, Mirzaie S, Ghiasvand R, Askari G, Miraghajani M. The effect of glutamine intake on complications of colorectal and colon cancer treatment: A systematic review. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(9):910–918. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.170634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang P, Tan G, Zhu M, Li W, Zhai B, Sun X. Hand-foot skin reaction is a beneficial indicator of sorafenib therapy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1373018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]