Abstract

Background

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a life-threatening mental disorder that is associated with substantial caregiver burden. Carers of individuals with AN report high levels of distress and self-blame, and insufficient knowledge to help their loved ones. However, carers can have a very important role to play in aiding recovery from AN, and are often highly motivated to assist in the treatment process. This manuscript presents the protocol for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of We Can, a web-based intervention for carers for people with AN. The study aims to investigate the effectiveness of We Can delivered with different intensities of support.

Methods

The study takes the form of a multi-site, two-country, three group RCT, comparing We Can (a) with clinician messaging support (We Can-Ind), (b) with moderated carer chatroom support (We Can-Chat) and (c) with online forum only (We Can-Forum). Participants will be 303 carers of individuals with AN as well as, where possible, the individuals with AN themselves. Recruitment will be via specialist eating disorder services and carer support services in the UK and Germany. Randomisation of carers to one of the three intervention conditions in a 1:1:1 ratio will be stratified by whether or not the individual with AN has (a) agreed to participate in the study and (b) is a current inpatient. The We Can intervention will be provided to carers online over a period of 12 weeks. Participants will complete self-report questionnaires at pre-intervention (T1), mid-intervention (mediators only; 4-weeks post-randomisation), post-intervention (T2; 3-months post randomisation), and 6 months (T3) and 12 months (T4) after randomisation. The primary outcome variables are carer symptoms of depression and anxiety. Secondary outcome variables will be measured in both carers and individuals with AN. Secondary carer outcome variables will include alcohol and drug use and quality of life, caregiving behaviour, and the acceptability and use of We Can and associated supports. Secondary outcomes measured in individuals with AN will include eating disorder symptoms, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. The study will also evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the three We Can conditions, and test for mediators and moderators of the effects of We Can. The trial is registered at the International Standard Randomisation Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) database, registration number: ISRCTN11399850.

Discussion

The study will provide insight into the effectiveness of We Can and its optimal method/s of delivery.

Abbreviations: AESED, accommodation and enabling scale for eating disorders; AN, anorexia nervosa; AQoL-8D, assessment of quality of Life-8D; AUDIT, alcohol use disorders identification test; BDSEE, brief dyadic scale of expressed emotion; BFI-10, Big Five – 10 item version; BMI, body mass index; CASK, caregiver skills scale; CD-RISC-10, Connor–Davidson resilience scale-10; CEQ, adapted credibility/expectancy questionnaire; CSRI, client service receipt inventory; DUDIT, drug use disorders identification test; ECI, experience of caregiving inventory; EDE-Q, eating disorder examination-questionnaire; EDSIS, eating disorders symptom impact scale; GAD-7, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)-7 scale; OAO, overcoming anorexia online; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire 9-item depression scale; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RSE, rosenberg self-esteem scale; WAI-SR, adapted working alliance inventory – short revised; We Can-Chat, We Can with moderated carer chatroom support; We Can-Ind, We Can with clinician email support; We Can-Forum, We Can with online forum support only; WHOQOL, World Health Organisation quality of life scale

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Carer support, Online interventions, E-treatment, Mental health, ICare

Highlights

-

•

The protocol for an RCT investigating the efficacy of an online intervention for carers of adults with anorexia nervosa.

-

•

The RCT will compare three study arms of the ‘We Can’ internet-based intervention.

-

•

We Can with clinician messaging support, moderated carer chatroom support, and online forum support only will be compared.

-

•

Primary outcomes of the study will consist of measurements of carer anxiety and depression.

1. Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a life-threatening mental disorder with substantial negative effects on physical, psychological, social and vocational functioning. AN is associated with substantial caregiver burden, similar or greater in magnitude to that seen with schizophrenia (Graap et al., 2008; Treasure et al., 2001). Carers of those with AN report intense distress, loneliness and isolation (Kamerling and Smith, 2010), self-blame regarding the illness (Whitney et al., 2005), and insufficient knowledge to effectively support their loved one (Graap et al., 2008; Haigh and Treasure, 2003).

The combination of high carer distress/self-blame and low carer knowledge/skills is concerning for two reasons. Firstly, it impacts on carers' own mental health, with significant proportions of carers scoring above the clinical threshold for an anxiety disorder or a depressive disorder (Kyriacou et al., 2008). Secondly, it may contribute to unhelpful carer behaviours such as high expressed emotion (EE) and accommodation to the illness (Zabala et al., 2009). These behaviours, in turn, have been shown to perpetuate eating disorder symptoms (Zabala et al., 2009). Interventions to address the unmet needs of carers of individuals with AN may therefore reduce burden on families and the health care system by their direct effect on the illness, as well as their indirect effect on carers' own mental health.

Together with professionals, service users and carers, our workgroup has developed a model of eating disorder carers' distress (Kyriacou et al., 2008; Treasure et al., 2005; Winn et al., 2007). Central to this model is the premise that, with opportunity and skills, carers of people with AN can have an important role to play in aiding the person's recovery, and are often highly motivated to assist in the treatment process (Treasure and Schmidt, 2001). Based on this model, we have developed We Can, a skills training programme for carers of people with AN. The programme is based on a systemic, cognitive-behavioural approach. We Can specifically targets unhelpful carer behaviours and attitudes that may inadvertently contribute to maintaining the illness, and also addresses carers' own needs.

We Can builds on and extends an earlier version of an online intervention for carers of individuals with AN (Overcoming Anorexia Online) developed by us and tested in two small randomised controlled trials, one in the UK (Grover et al., 2011) and one across Australia and the UK (Hoyle et al., 2013). In the UK trial, 64 carers were randomly allocated to receive either the online intervention with clinician support (by email or phone), or to ad-hoc support-as-usual from the UK eating disorder charity B-EAT. At 4-months and 6-months post-randomisation, carers in the online intervention group showed significantly greater reductions in anxiety and depression than those in the support-as-usual group. There was a similar although non-significant trend towards greater reductions in EE. In the Australia-UK trial, 37 carers were randomly allocated to receive the online intervention either with clinician support or without such support. At 4-months and 7-months post-randomisation, both online intervention conditions were associated with significant reductions in carer intrusiveness, negative experiences of caregiving, and the impact of starvation and guilt. Few significant between-group differences were identified, but effect sizes tended to favour the condition with clinician support. Effect sizes also showed a large decrease in the perceived intrusiveness of the carer by the individual with AN, for both groups, although this effect did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07).

These early trials provide initial support for the efficacy of online interventions for carers of individuals with AN. However, further research is needed to extend these results, and to clarify if online carer interventions with clinician support are more effective than online interventions alone. It would also be helpful to identify mediators and moderators of any programme effects, so that online interventions such as We Can can be used to provide maximum carer and patient benefits.

Within the broader field of online interventions for carers with mental disorders, evidence regarding the efficacy of such interventions is limited, with mixed findings being obtained from a relatively small number of studies. A recent systematic review (Spencer, 2017) found eleven studies reporting on how online carer interventions impacted on carer mental health. In addition to the two studies detailed above focusing on carers of individuals with anorexia, studies identified through the literature search included one study reporting that an online intervention for carers of individuals with depression was found to be user-friendly, but did not improve carer outcomes of psychological distress (Bijker et al., 2017), and two studies focused on carers of individuals with schizophrenia, which found the interventions did not impact carer stress and distress, but other relevant outcome measures did show some positive associations with the interventions (Glynn et al., 2010; Rotondi et al., 2005). Four studies were found where the intervention was not targeted towards carers of individuals with a specific mental illness, but rather, where the participant samples consisted of carers with a mixed array of mental health difficulties. Again, findings regarding the effectiveness of the interventions were mixed, but improvements were found with regards to carer quality of life, perceived stress, and mindfulness (Ali et al., 2014; Gleeson et al., 2017; Stjernswärd and Hansson, 2017a; Stjernswärd and Hansson, 2017b).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Objectives and hypotheses

The overall aim of the proposed study is to investigate the effectiveness of We Can with different intensities of support, in carers of individuals with AN.

The study takes the form of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT) of We Can with clinician messaging support (We Can-Ind) or moderated carer chatroom support (We Can-Chat) versus We Can with online forum only (We Can-Forum).

Specific aims are as follows:

-

1.

To compare the effectiveness of We Can-Ind or We Can-Chat versus We Can-Forum on carer outcomes (including programme acceptability and carer behaviour, distress and quality-of-life).

-

2.

To compare the effectiveness of We Can-Ind or We Can-Chat versus We Can-Forum on patient outcomes (including perceived levels of carers' EE, and patient eating disorder pathology, distress and quality-of-life).

-

3.

To compare the cost-effectiveness of We Can-Ind, We Can-Chat and We Can-Forum.

-

4.

To test for mediators and moderators of We Can effects.

The following hypotheses have been made:

-

1.

Carers who receive We Can-Ind or We Can-Chat will find this more acceptable and will show greater reductions in depression, anxiety, alcohol/substance use, EE, accommodation and enabling behaviours and caregiving burden, as well as greater improvements in quality of life, compared to carers receiving We Can-Forum.

-

2.

Patients with carers allocated to We Can-Ind or We Can-Chat will show greater improvements in perceived carer EE as well as their own eating disorder symptoms, distress and quality of life, compared to patients whose carers were allocated to We Can-Forum.

-

3.

We Can-Ind and We Can-Chat will be more cost-effective than We Can-Forum.

-

4.

Changes in carer behaviours (EE, accommodating and enabling) over We Can will mediate any improvements in patients' eating disorder symptoms.

-

5.

We Can (any version) will produce greater benefits for carers with high levels of EE and accommodating and enabling behaviour at baseline (i.e., those carers for whom the intervention is most relevant).

It is also predicted that living situation, amount of face-to-face contact, and duration of illness will moderate the effects of We Can. However, specific hypotheses were not made regarding these effects.

2.2. Participants

The study will recruit 303 carers of adults or adolescents (individuals aged 16 or over at the beginning of the study) with AN. A maximum of one carer per individual with AN will be eligible to participate in the study. Where possible, the individuals with AN cared for by these carers will also be recruited into the study, in order to assess whether carer participation in We Can is associated with change in eating disorder symptomatology, or the experience of receiving care.

Inclusion criteria are: being a carer of an individual with AN (adolescent or adult) and being fluent in English or German. The definition of “carer” used is that of the Princess Royal Trust for Carers (UK Charity) (www.carers.org) and includes partners, siblings and other relatives or friends who provide unpaid help and support.

Exclusion criteria are caring for someone with an eating disorder other than AN (e.g., bulimia nervosa) who has never received a diagnosis of AN (caring for an individual who has previously been diagnosed with AN but does not currently meet all of the diagnostic criteria, for example who has been recently weight-restored through treatment, would not preclude a carer from being included within the study), a current eating disorder or other severe mental health difficulty in the carer, or inability of the carer to read and understand English or German.

Exclusion criteria for individuals with AN whose carers are participating in the study are being currently dependent on drugs or alcohol, or diagnosed with a current major psychological disorder, which would interfere with their ability to complete the relevant questionnaires (for example, psychosis, or severe suicidal depression).

2.3. Study design

This study is a two-country, multi-site pragmatic RCT, comparing the effectiveness of three forms of a web-based skills training programme for carers of those with AN (We Can). The three groups are therapist-guided messaging support (We Can-Ind), peer-guided moderated chatroom support (We Can-Chat), and online forum support only (We Can-Forum).

Carers will be recruited and randomly assigned to one of the three intervention conditions. Randomisation will be stratified by whether or not the relevant individual with AN (a) has agreed to participate in the study themselves and (b) is currently an inpatient (as these factors may affect outcome).

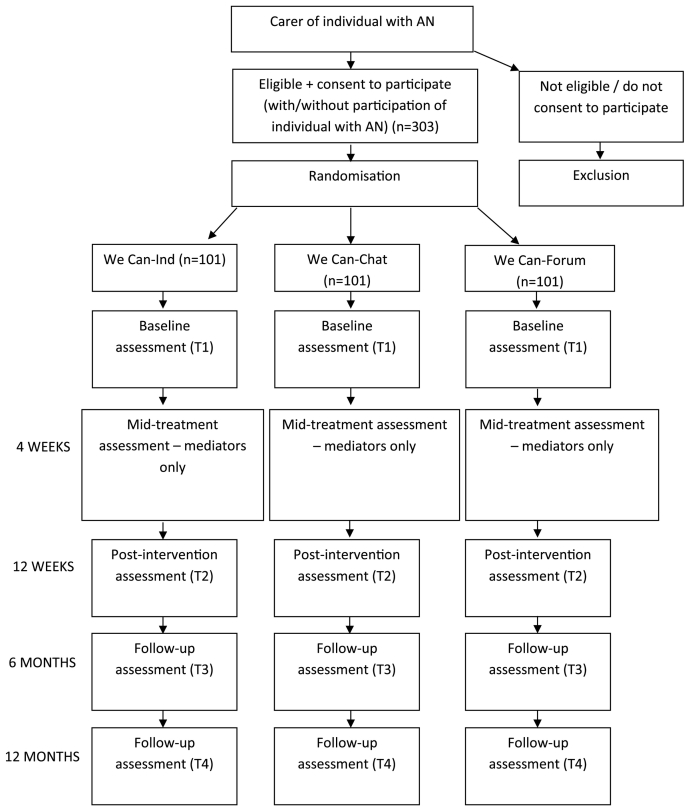

Assessments will be conducted at pre-intervention (T1), mid-intervention (mediators only; 4-weeks post-randomisation), post-intervention (T2; 3-months post randomisation), and 6 months (T3) and 12 months (T4) after randomisation (follow-up assessments). The study flow is indicated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow.

The primary comparison point is from T1 to T2. The primary outcomes will be changes in carer depression, as measured by the Primary Health Questionnaire 9-item depression scale (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002; German version: Löwe et al., 2002), and generalized anxiety, as measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006; German version: Löwe et al., 2002). A full list of the outcome measures assessed at each time point can be found in Table 1 (carer outcome measures) and Table 2 (participant with AN outcome measures). Additionally, carers will be asked to rate how useful they found each module on a Likert scale (where 1 = Not at all useful, and 5 = Very useful indeed).

Table 1.

Measurement times of carer measures.

| Measure | Screening (T0) |

Baseline (T1) |

4 weeks after start of intervention (Mediators only) |

Post-intervention (T2) |

6 month follow up (T3) |

12 month follow up (T4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | x | x | ||||

| AUDIT | x | x | x | x | x | |

| AQoL8D | x | x | x | x | ||

| AESED | x | x | x | x | ||

| BFI-10 | x | |||||

| CSRI | x | x | x | x | ||

| CD-RISC10 | x | x | x | x | ||

| CEQ | x | x | ||||

| CASK | x | x | x | x | ||

| DUDIT | x | x | x | x | ||

| EDSIS | x | x | x | x | ||

| ECI | x | x | x | x | ||

| GAD7 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| PHQ9 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| RSE | x | x | ||||

| WAI-SR | x |

Table 2.

Measurement times of participant with AN measures.

| Measure | Screening (T0) |

Baseline (T1) |

4 weeks after start of intervention (Mediators Only) |

Post-intervention (T2) |

6 month follow up (T3) |

12 month follow up (T4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables |

x |

x | ||||

| AUDIT | x | x | x | x | x | |

| AQoL8D | x | x | x | x | ||

| BDSEE | x | x | x | x | x | |

| BMI | x | x | x | x | x | |

| CSRI | x | x | x | x | ||

| EDE-Q | x | x | x | x | ||

| GAD7 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| PHQ9 | x | x | x | x | x |

The RCT will be conducted in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 Statement (Moher et al., 2001) and the CONSORT-EHEALTH Statement (Eysenbach and Consort-Ehealth Group, 2011). The study follows the guidelines of Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT).

The trial is registered at the International Standard Randomisation Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) database, registration number: ISRCTN11399850. Ethical approval for the trial was granted in the UK by the North West – Greater Manchester East Research Ethics Committee (REC; reference number 16/NW/0885) on 1st February 2017, and by the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 28th February 2017, and in Germany by the Ethics Committee at the Technical University Dresden, Germany (reference number EK 500122016), was received on December 1st, 2016.

The research team does not expect there to be any significant modifications to the study protocol. Any unexpected changes will be reported to the relevant research authorities and trial registries by research teams in the UK and Germany. Communication with study participants of any unexpected modifications to the study will occur via email and the Minddistrict internal messaging system. Researchers from the different study sites are in regular communication via email, video-call, and face-to-face meetings.

3. Intervention

As noted, We Can is a web-based interactive skills training intervention for carers of individuals with AN, adapted from an earlier version of the programme (Overcoming Anorexia Online; Grover et al., 2011). The intervention is based on a systemic and cognitive-behavioural model and comprises eight interactive modules designed for carers of adolescents and adults with AN at any illness stage. The modules are delivered via a website and can be used with clinician or peer support, or independently. The programme was co-produced by a team with expertise in the development of eating disorder treatments for children and adults, as well as expertise in cognitive-behavioural therapy, family-based treatments and self-help treatments. The team also included a carer and a person who had recovered from AN.

Content of the We Can modules includes information regarding: the symptoms of AN; how carers can begin to develop the skills needed to communicate effectively with a person who is ambivalent about change (by teaching them the principles of motivational interviewing); helping carers to identify, understand, and formulate how unhelpful behaviours and avoidance can result from difficult situations; and teaching carers how to provide meal support to their loved one. In addition, the modules provide information on the risk and prognosis of AN, managing bingeing, purging, and other difficult behaviours, and strategies to help prevent relapse. Finally, the intervention assists carers with identifying their own needs, and helps them to develop a plan to meet their own needs.

In this study, carers will be randomly assigned to one of three conditions: therapist-guided (We Can-Ind), peer-guided (We Can-Chat), and We Can with forum support only (We Can-Forum). Random assignment to one of the three conditions will be stratified by whether or not the individual with AN has (a) agreed to participate in the study and (b) is in inpatient treatment for their eating disorder when their carer commences participation in the study. Once participants have been deemed eligible for the study, and completed the baseline assessments, a member of the research team will randomly allocate them to one of the three conditions via a computer programme. Participants will then be informed by the research team which condition they have been allocated to, via the Minddistrict messaging system. Due to the nature of the study, neither participants nor the research team will be blinded to participant condition assignment.

In each of the three conditions, carers will have access to the 8 online modules (with a new module released one week after completion of the previous module), and access to a moderated online forum, where they can communicate with other participating carers during and after the intervention (asynchronous support). The forum acts as a platform for participants to share problems, solutions and successes. Participants will be encouraged to use the forum throughout the 12-week intervention period.

In We Can-Ind, carers will have additional weekly contact with a trained therapist via the Minddistrict internal messaging system to discuss their use of the programme and to receive motivational support. This support will last for 12 weeks. In the context of this study, “therapists” will consist of PhD students, post-graduate research assistants, Assistant Psychologists, and other clinical staff with experience of providing support to individuals with mental health difficulties, and working with online interventions. Therapists will receive half a day of training regarding the provision of online support, a set of example responses, and ongoing support from the research team to resolve any issues or queries that occur over the duration of the study.

In We Can-Chat, carers will additionally receive access to an online chat-room in which they can communicate with other participating carers at scheduled times (once per week, for 12 weeks). These chat sessions will be moderated by a trained therapist (synchronous support). Therapists will receive half a day of training regarding the facilitating of online carer groups, a set of example responses and potential topics of discussion, and ongoing support from the research team to resolve any issues or queries that occur over the duration of the study.

In We Can-Forum, carers will complete We Can independently, with access to the moderated online forum only.

All online content will be delivered via the web-based treatment platform Minddistrict (www.minddistrict.com). Minddistrict is a secure, e-health platform, which participants, researchers, and therapists are able access via a personal account. Participants are able to view and access the activities that are available to them (e.g. We Can modules, pending questionnaires), message other carers via the online forum, and (dependent on group allocation), contact their individual therapist, or visit the scripts of previous online chat-room conversations they participated in.

Therapists and members of the research team are able to monitor the progress of participants, and establish whether they have completed their allocated activities. Therapists and researchers are then able to use the messaging system to remind participants of any pending activities, and communicate with one another also via the messaging system.

In order to ensure adherence to the intervention protocol, therapists providing support via individual messaging, or moderating the online chat-room will receive training prior to beginning their role as a therapist within the study, and ongoing support and supervision from clinicians with specialist experience of working with eating disorders and online interventions.

Participants will not be permitted to be re-assigned to a different study condition at any time. However, participants will be informed that their participation in the study is entirely voluntary, and they are permitted to discontinue their involvement in the study at any time, without being required to give a reason.

3.1. Procedure

This study is part of a European multi-centre study and participants will be recruited both in the UK and in Germany. The intention is to recruit 70% of the required sample in the UK (n = 212). Carers in the UK will be recruited through 4 routes, including:

1. The Adult Eating Disorders Outpatient Service at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. This service receives approximately 250 new referrals for AN per annum, with about 80% of those (n = 200) having carers involved in treatment and keen to access support and guidance.

2. Other specialist eating disorders services across the UK.

3. The annual national UK eating disorders carers conference, which attracts approximately 100–150 carers of people with AN.

4. B-EAT, the UK patient carer organisation for people with eating disorders. B-EAT advertise research projects for patients and carers, and we have recruited successfully through this organisation for several similar projects in the past.

Carers recruited in Germany will be recruited through cooperating psychosomatic hospitals with eating disorder units, counselling centres, GPs as well as paediatricians, and psychotherapists. Recruitment will also take place via press releases, Facebook posts, and announcements on several eating disorder specific websites.

Should carers decide to take part, they will be asked to complete a brief screening questionnaire to determine their eligibility for the study. If they are eligible and have given informed consent to participate (please contact corresponding author for model copies of participant consent and information forms), carers will be randomly allocated to one of the three intervention conditions and receive access to the baseline (T1) assessment and the intervention modules. All assessment measures will be embedded in the online platform for We Can, with participants` responses being stored on the online platform for the duration of the study. Only members of the research team will be able to access participants` responses to questionnaires for the purpose of data monitoring and analysis (see below).

Carers will be asked to complete the intervention modules within 12 weeks of being allocated to their condition. Post-intervention and follow-up assessments will be completed at 3, 6, and 12 months post-randomisation. Where the individual with AN is participating, they will also be asked to complete measures online at these same assessment points.

Participants will be prompted to complete the online modules and assessments via reminder emails/messages sent from researchers through the Minddistrict messaging service. If participants drop out from the study after having provided baseline data, or decline to complete the full set of outcome measures, the research team will attempt to gather information on the primary outcome measures (PHQ-9 and GAD-7; see below) at relevant timepoints.

In cases where carers are approached first, they will also be provided with information material for the individual with AN and asked to invite their loved one to participate in the project. However, carers are able to participate in this study without their loved one participating. In cases where patients are approached first, they will be provided with information material for their carer/s and asked to invite their carer/s to participate in the project. Individuals with AN will only be able to participate in the study if their carer is participating.

Carers will be randomily allocated in a 1:1:1 ratio to the three groups We Can-Ind, We Can-Chat, and We Can-Forum. For the primary analysis, We Can-Ind and We Can-Chat will be combined for comparison with We Can-Forum. Thus, sample size calculations are based on a 2:1 randomisation ratio. There are no restrictions on either carers or individuals with anorexia from receiving other forms of support for the duration of their participation in We Can.

Findings from this trial will be disseminated via publication in peer-reviewed journals, and presentation of the findings at national and international conferences.

3.2. Assessment and data management

All study data will be collected on the respective study platforms provided by ICare partner Minddistrict (www.minddistrict.com).

A data management plan will be implemented to guarantee data accuracy, composition and organisation, completeness, transparency of processes, and timeliness. Data will be checked for internal validity by plausibility rules. Harmonized data management and quality monitoring will be provided by the Institute for Biostatistics and Clinical research of the University of Münster, Germany for the whole consortium, in order to maintain comparable high quality in the conduct of the ICare research projects. After export from the collected study data will be processed in a unified manner, using programming scripts implemented in the SAS software (SAS Inc., Cary, NY, USA). Collected study data is protected effectively, as defined in a data protection plan. All data transfer will be encrypted using secure standards, e.g. AES256. Participants and study personnel can access the Minddistrict platform only via secure-socket-layer (SSL) encrypted connections (HTTPS-protocol). Also any data exchange between data management and the trial principal investigator will be encrypted.

3.3. Outcomes

All measures are self-report questionnaires, to be completed online via the Minddistrict platform.

3.3.1. Primary carer outcome measures

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002; German version: Löwe et al., 2002). The PHQ is a self-report version of the clinician-administered PRIME-MD diagnostic instrument for mental disorders, and is commonly used in primary care and community settings (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002). The 9-item depression module (PHQ-9) assesses depressive symptoms over the previous 2 weeks. It provides a screen for DSM major depressive disorder and generates a symptom severity score that can range from 0 to 27. In a validation study with two large primary care samples (n > 3000), the PHQ-9 demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.86) and 48-h test-retest reliability (r = 0.84) as well as good convergent validity (Kroenke et al., 2001). The measure also shows good sensitivity to change (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002), making it suitable for use as a primary outcome measure.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006; German version: Löwe et al., 2002). The GAD-7 assesses symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder over the previous 2 weeks. It serves as a screening instrument for DSM generalized anxiety disorder and generates a symptom severity score that can range from 0 to 21. In the initial validation study with 2740 primary care patients, the GAD-7 demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.83) and good convergent and discriminant validity (Spitzer et al., 2006). Similar results have been reported in subsequent community and primary care studies (e.g., Löwe et al., 2008) and the scale also shows good sensitivity to change over time (Robinson et al., 2010).

3.3.2. Secondary carer outcome measures

3.3.2.1. Socio-demographic data and further information relating to carer

At the screening and baseline time points, carers will be asked a range of questions relating to a number of socio-demographic variables (including carer age, gender, ethnicity, education, and marital status). Additionally, further questions will be asked when screening participants to establish their relationship to the individual with the eating disorder for whom they care, any previous experiences of psychological therapy, and whether they are currently suffering from an eating disorder (or other mental health difficulty) that may prevent them from being able to effectively engage in the intervention as a carer.

3.3.2.2. Session ratings

In order to help evaluate the perceived helpfulness of each of the online modules, carers will be asked to rate each session on a 1–5 Likert-type scale following session completion.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor et al., 2001; German version: Wurst et al., 2013). The AUDIT is one of the most commonly used measures of alcohol use and misuse. A systematic review concluded that it is the best screening instrument for the whole range of alcohol problems in primary care (Fiellin et al., 2000) and the measure has excellent psychometric properties including internal consistency, test-retest reliability and convergent validity. The AUDIT consists of 10 items and generates total scores that can range from 0 to 40. A score of 8 or higher suggests possible hazardous and harmful alcohol use.

Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) (Berman et al., 2004). The DUDIT was developed as a parallel instrument to the AUDIT and assesses drug use and drug-related problems. Reported alpha coefficients exceed 0.80 and it shows good convergent validity (Berman et al., 2004; Voluse et al., 2011). The DUDIT consists of 11 items and generates total scores that can range from 0 to 44.

Caregiver Skills (CASK) scale (Hibbs et al., 2015; German version: unpublished translation). The CASK was specifically developed to assess caregiver skills that may be helpful for people with AN. It was developed by clinicians and researchers in conjunction with caregivers and includes 27 items that assess skills on six subscales: bigger picture, self-care, biting-your-tongue, insight and acceptance, emotional intelligence, and frustration tolerance. All subscales show acceptable internal consistency (αs > 0.70) and good convergent validity as well as sensitivity to change (Hibbs et al., 2015).

Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale (EDSIS) (Sepulveda et al., 2008; German version: unpublished translation). The EDSIS was specifically developed to assess the caregiving burden of AN and bulimia nervosa. As with the CASK, it was co-produced by clinicians and researchers with carers. The measure includes 24 items assessing symptom impact on four subscales: nutrition, guilt, dysregulated behaviour, and social isolation. All subscales show excellent internal consistency (αs > 0.80) and good convergent validity as well as sensitivity to change (Sepulveda et al., 2008).

Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders (AESED) (Sepulveda et al., 2009; German version: unpublished translation). The AESED was specifically developed to assess carer accommodation to eating disorder symptoms. As with the CASK and EDSIS, it was developed by clinicians and researchers in conjunction with carers. The AESED includes 33 items assessing accommodating and enabling behaviour on five subscales: avoidance and modifying routines, reassurance seeking, meal rituals, control of family, and turning a blind eye. All subscales show good internal consistency (αs > 0.77) and acceptable convergent validity. Total scores show good sensitivity to change, as do scores on the avoidance and modifying routines, meal rituals, and control of the family subscales (Sepulveda et al., 2009).

Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) (Szmukler et al., 1996; German version: Burfeind et al., 2013). The ECI includes 66 items assessing negative and positive aspects of caregiving. Negative aspects (caregiver distress) are scored on eight subscales: negative symptoms, stigma, effects on family, the need to provide backup, dependency, problems with services, difficult behaviours, and loss. Positive aspects (caregiver rewards) are scored on two subscales: positive personal experiences and good aspects of the relationship. All subscales show good internal consistency (αs > 0.74) and convergent and divergent validity (Szmukler et al., 1996; Joyce et al., 2000).

Assessment of Quality of Life-8D (AQoL-8D) (Richardson et al., 2011; German version: Centre for Health Economics, n.d, Monash University). The AQoL-8D is a 35 item instrument for the assessment of quality of life and comprises 8 dimensions – independent living, pain, senses, relationships, mental health, happiness, coping, and self-worth. The AQoL-8D has been found to have good levels of reliability and validity in comparison with other existing multi-attribute utility instruments, particularly where the psychosocial elements of health are of high importance (Richardson et al., 2014).

Big Five – 10 Item Version (BFI-10) (Rammstedt and John, 2007). The BFI-10 is an abbreviated version of the well-established Big Five Inventory (BFI), which originally employed 44 items to assess five dimensions of personality – openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (John et al., 1991). This shortened version of the BFI was developed simultaneously in both English and German, increasing the cross-cultural validity of the measure. The BFI-10 was found to retain significant levels of reliability and validity, while requiring a significantly shorter amount of time for respondents to complete than the 44-item BFI (Rammstedt and John, 2007).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) (Rosenberg, 1965; German version: Ferring and Filipp, 1996). The RSE is a 10-item, Likert-type scale measuring levels of global self-esteem, where respondents indicate to what degree on a four-point scale (ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) they endorse statements relating to their own self-worth and self-acceptance. The scale was initially developed from a large sample of High School students from New York State, and has subsequently been utilized within a wide range of populations. A recent study (Roth et al., 2008) using a representative population sample, evidenced that the RSES is a two-dimensional scale (comprising positive and negative self-esteem), which constitutes a unitary construct of global self-esteem.

Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) – Carer Version (Beecham and Knapp, 2001). The CSRI was developed to collect information on service utilisation, service-related issues and income (including lost income due to health conditions). Responses allow for an estimate of service use costs per participant. The carer-report version asks carers to report on their loved one's service use, in addition to assessing the impact of caring on a carer's own health and use of services. Time spent caregiving, and the impact of caregiving on working hours and productivity are also measured.

Adapted Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ; Devilly and Borkovec, 2000; German version: unpublished translation). The CEQ is a 6-item self-report measure, assessing the respondent's beliefs about the outcome of the treatment they are receiving. Two distinct but related factors (the cognitively-based credibility of the treatment, and relatively more affectively-based expectancy for improvement) are measured, with the questionnaire being shown to have high levels of internal consistency within the two factors, and good test-retest reliability (Devilly and Borkovec, 2000).

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC-10) (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007; German version: unpublished translation by Ebert and Zarski, 2014). The CD-RISC-10 is a briefer version of the full 25-item version of the scale, assessing resilience through a 10-item self-report questionnaire. The 10-item version used within the current study has been found to display good levels of internal consistency and construct validity (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007), providing an effective way to measure the ability of an individual to manage during adversity.

Adapted Working Alliance Inventory – Short Revised (Adapted WAI-SR) (Hatcher and Gillaspy, 2006; German version: Wilmers et al., 2008; adapted for online interventions). The adapted WAI-SR is a 12-item scale for the measurement of the therapeutic alliance in online programmes. Working alliance comprises three aspects; agreement on therapy goals, agreement on included tasks, and the bond between participant and online supporting clinician. The third aspect (bond), will only be assessed in the We Can-Ind study arm, in which participants receive clinician support.

3.3.3. Secondary outcome measures in individuals with AN

3.3.3.1. Socio-demographic data

At the screening and baseline time points, individuals with AN will be asked a range of questions relating to a number of socio-demographic variables.

3.3.3.2. Body mass index (BMI)

Individuals with AN will be asked to self-report their height and weight so that BMI can be calculated using the standard formula (weight [kg]/height [m]2). Where patients are engaged in treatment with a site collaborating with the project, we will also seek consent to collect their BMI from clinical notes.

3.3.3.3. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire (EDE-Q) (Fairburn and Beglin, 1994; German version: Hilbert and Tuschen-Caffier, 2006)

The EDE-Q is a self-report version of the well-established interview version of the EDE (Fairburn and Cooper, 1993), consisting of a series of questions regarding eating disordered behaviours, and concerns over shape and weight, over the past 28 days. The EDE-Q has been used extensively in both screening and the measuring of clinical change in populations of individuals with eating disorders, and has been found to be a reliable measure (Mond et al., 2004).

3.3.3.4. Patient health questionnaire (PHQ)-9 (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002; German version: Löwe et al., 2002)

The 9-item depression module of the PHQ will be used to assess depressive symptoms in individuals with AN, as well as their carer/s. The measure is described above.

3.3.3.5. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006; German version: Löwe et al., 2002)

The GAD-7 will be used to assess symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in individuals with AN, as well as their carer/s. The measure is described above.

3.3.3.6. Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) (Babor et al., 2001; German version: Wurst et al., 2013)

The AUDIT will be used to measure alcohol use and misuse in individuals with AN, as well as their carer/s. The measure is described above.

Brief Dyadic Scale of Expressed Emotion (BDSEE) – Patient version (Medina-Pradas et al., 2011; German version: unpublished translation). The patient-report version of the BDSEE will be completed by individuals with AN. The patient-report version of this measure assesses perceived criticism, emotional over-involvement and warmth from the carer. The BDSEE has been shown to be a valid measure of perceived expressed emotion in an adolescent population (Schmidt et al., 2016).

Assessment of Quality of Life-8D (AQOL-8D) (Richardson et al., 2011; German version: Centre for Health Economics, Monash University). The AQoL-8D is used to assess 8 dimensions of quality of life. The measure is described above.

Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) – Patient Version (Beecham and Knapp, 2001). The CSRI will be used to assess self-reported service utilisation and loss-of-income in individuals with AN, alongside reports collected from their carer/s. The measure is described above.

3.4. Statistical methods

Data will be analysed using linear mixed models. Separate models will be calculated for each primary and secondary outcome variable. Each model will include We Can group (We Can-Ind; We Can-Chat; We Can-Forum) and time (T1/pre-randomisation; T2/post-intervention; T3/6 months post-randomisation; T4/12-months post-randomisation) as predictor variables. Additional predictors will be added to models as necessary following initial descriptive analyses, e.g. baseline characteristics of participants or variables associated with programme non-completion.

As noted, data from the We Can-Ind and We Can-chat groups will be pooled for comparison with We Can-forum, and the primary comparison point is T1 to T2. Primary analyses will be performed on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. A multiple imputation strategy will be employed for missing data.

As this study is part of a European multi-centre trial, statistical analyses will be conducted by a biostatistician at one of the partnering institutions in Germany (University of Münster). The statistician will have access to data from all sites (UK and Germany).

The cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) will employ data from the primary clinical outcome measure (PH9) and we will also explore the potential of the AQoL-8D to undertake a cost utility analysis (CUA) using previously developed algorithms to calculate the gain in quality of life adjusted years (Dakin, 2013). Both analytic modes will employ costs from the CSRI data on use of services and supports, insofar as possible using both a public sector and a societal perspective. Established, theory-driven approaches will be used to estimate unit costs for services (Beecham, 2000), including the We Can interventions, which will then by multiplied by each individual use of supports as recorded on the CSRI. OECD purchasing power parity data will be used to standardise costs between countries. Findings from the economic analyses will be presented descriptively and as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, which show the probability of cost-effectiveness at a range of willingness to pay values.

3.5. Sample size calculation

For the primary endpoints, differences in the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 for carers, the two guided intervention conditions (We Can-Ind and We Can-chat) will be compared to the active control (We Can-Forum) using a two-sided, two-sample t-test, assuming normal distribution of the differences in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores within each group. Based on Grover et al., 2011 we assume a smallest relevant effect of d = 0.53 (Cohen's d).

To detect an effect of, at least, d = 0.53, with a probability of 90% (Type-II Error β = 10%) on a significance level of α = 1% using a two-sided two-sample t-test, at least N = 242 carers need to be included in the trial. Based on our previous studies we assume a dropout rate of 20% at T2 and thus N = 303 carers are required to be recruited into the study.

4. Discussion

This manuscript summarises the protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a systemic, cognitive-behavioural, web-based programme for carers of individuals with AN (We Can). The study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of We Can in reducing caregiver distress and unhelpful behaviour, and in reducing distress and eating disorder symptoms in the individuals with AN for whom they care. Establishing the effectiveness of We Can is important because there is a significant burden associated with caring for someone with AN, and carers are at risk of developing mental health difficulties themselves (Kyriacou et al., 2008). Furthermore, carers have the potential to support effective treatment for AN (Treasure et al., 2005; Hibbs et al., 2014). Clinical guidelines also recommend that carers of individuals with eating disorders are routinely provided with information and support relating to the disorder (NICE, 2017). Support for We Can in this study would add to the small body of existing evidence for online carer interventions, and facilitate their wider dissemination.

This study also aims to compare the relative effectiveness of three different ways of delivering We Can: with clinician messaging support (We Can-Ind) and moderated carer chatroom support (We Can-Chat) versus online forum support only (We Can-Forum). There is a primary focus on changes in carer depressive and anxiety symptoms, as these are recognised as key areas of difficulty for carers of those with AN (Kyriacou et al., 2008). Support for the study's hypotheses would see We Can-Ind and We Can-Chat produce greater reductions in carer distress than We Can-Forum, and also demonstrate greater cost-effectiveness. This pattern of results would suggest that We Can should be delivered with guidance and support and, again, would inform the dissemination of the programme and the provision of best-practice support for carers. A randomised control design provides the optimal means for comparing the different forms of We Can in a methodologically rigorous way.

In addition to testing the overall effectiveness of We Can and evaluating the relative benefits of different We Can formats, the study will consider mediators and moderators of programme effects. This is a strength of the research as it may allow carers to be matched to We Can according to their presenting characteristics, or, if resources are limited, for We Can to be offered to those most in need of the programme. Additional strengths of the proposed research include collaboration between research and clinical teams across the UK and Germany, which will facilitate recruitment and increase the generalisability of results; the collection of a broad range of data covering both mental health symptoms and caregiver behaviour; and, where possible, the collection of data from carers and the individuals they care for.

The main limitation of the RCT is that all conditions involve We Can and, accordingly, We Can is not being compared to an alternative carer support programme or to no support. At present, there is no similar carer support programme to provide a viable comparison treatment to We Can. Furthermore, as evidence already exists for the efficacy of online carer interventions over support-as-usual (Grover et al., 2011), it did not seem appropriate to include a no-support or support-as-usual condition. We expect the results of this trial to further research into support options for carers with AN, so that ongoing progress may be made with considering different ways to provide effective guidance and support to this group.

A recent systematic review into the effectiveness of online interventions on improving carer mental health has found the existing evidence to be mixed, and consisting of a limited number of studies, a considerable proportion of which are not RCTs (Spencer, 2017). Findings from the We Can study will increase the existing knowledge relating to this field, and develop the evidence-base regarding how best to support carers of individuals with mental health difficulties.

Trial status

The first participants were enrolled in the study on 8th May 2017. Follow-up assessments for the remaining patients are expected to be completed by late 2019.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing or conflicting interests.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no 634757. Ulrike Schmidt is supported by a Senior Investigator award from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and receives salary support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London. The views expressed herein are not those of NIHR or the NHS.

Study funders have no involvement in the study design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, writing of this report, or decision to submit this report for publication.

Author contributions

US and PM designed the study. DG and JB contributed significantly to the study design. KA wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and LS updated the draft prior to submission. All other authors contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all our participants for their support without whom this study would not be possible. The study will be part of the doctoral thesis of LS.

Contributor Information

Lucy Spencer, Email: lucy.spencer@kcl.ac.uk.

Juliane Schmidt-Hantke, Email: juliane.schmidt-hantke@tu-dresden.de.

Karina Allen, Email: karina.allen@kcl.ac.uk.

Gemma Gordon, Email: gemma.gordon@kcl.ac.uk.

Rachel Potterton, Email: rachel.h.potterton@kcl.ac.uk.

Peter Musiat, Email: peter.musiat@kcl.ac.uk.

Franziska Hagner, Email: franziska.hagner1@tu-dresden.de.

Ina Beintner, Email: ina.beintner@tu-dresden.de.

Bianka Vollert, Email: bianka.vollert@tu-dresden.de.

Barbara Nacke, Email: barbara.nacke@tu-dresden.de.

Dennis Görlich, Email: dennis.goerlich@ukmuenster.de.

Jennifer Beecham, Email: j.beecham@lse.ac.uk.

Eva-Maria Bonin, Email: e.bonin@lse.ac.uk.

Corinna Jacobi, Email: corinna.jacobi@tu-dresden.de.

Ulrike Schmidt, Email: ulrike.schmidt@kcl.ac.uk.

References

- Ali L., Krevers B., Sjöström N., Skärsäter I. Effectiveness of web-based versus folder support interventions for young informal carers of persons with mental illness: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014;94:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T.F., Higgins-Biddle J.C., Saunders J.B., Monteiro M.G. World Health Organization; 2001. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. [Google Scholar]

- Beecham J. Joint publication from the Department of Health; Personal Social Services Research Unit and Dartington Social Care Research Unit: 2000. Unit Costs: Not Exactly Child's Play.http://www.pssru.ac.uk/archive/pdf/B062.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Beecham J., Knapp M. Costing psychiatric interventions. In: Thornicroft Graham., editor. Measuring Mental Health Needs. Gaskell; London, UK: 2001. pp. 200–224. [Google Scholar]

- Berman A.H., Bergman H., Palmstierna T., Schlyter F. Evaluation of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur. Addict. Res. 2004;11:22–31. doi: 10.1159/000081413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijker L., Kleiboer A., Riper H.M., Cuijpers P., Donker T. A pilot randomized controlled trial of E-care for caregivers: an internet intervention for caregivers of depression patients. Internet Interventions. 2017;9:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burfeind A., Unser J., Steege D., Rumpf H.J., Lencer R. The quality of life in relatives giving care to patients with psychotic disorders is mainly determined by their internal locus of control. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr. 2013;81(4):195–201. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Health Economics M. U. AQoL-8D. http://aqol.com.au/documents/translations/AQoL-8D_German_Data_Collection.pdf Retrieved from.

- Dakin H. Review of Studies Mapping From Quality of Life or Clinical Measures to EQ-5D: An Online Database. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 11, 151. HERC Database of Mapping Studies, Version 3.0 (Last updated: 26th June 2014) 2013. http://www.herc.ox.ac.uk/downloads/mappingdatabase Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Devilly G.J., Borkovec T.D. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Zarski A.C. Friedrich-Alexander Universität; Erlangen-Nürnberg: 2014. Deutsche Version Der Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (Unpublished) [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G., Consort-Ehealth Group CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Beglin S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Cooper Z. Binge eating: nature, assessment and treatment. In: Fairburn C.G., Wilson G.T., editors. The Eating Disorder Examination. Twelfth Edition. Guildford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ferring D., Filipp S.H. Messung des Selbstwertgefühls: Befunde zu Reliabilität, Validität und Stabilität der Rosenberg-Skala. Diagnostica. 1996;42(3):284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin D.A., Carrington R.M., O'Connor P.G. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:1977–1989. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson J., Lederman R., Koval P., Wadley G., Bendall S., Cotton S.…Alvarez-Jimenez M. Moderated online social therapy: a model for reducing stress in carers of young people diagnosed with mental health disorders. Front. Psychol. 2017:8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn S.M., Randolph E.T., Garrick T., Lui A. A proof of concept trial of an online psychoeducational program for relatives of both veterans and civilians living with schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Rehab. J. 2010;33(4):278. doi: 10.2975/33.4.2010.278.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graap H., Bleich S., Herbst F., Trostmann Y., Wancata J., de Zwaan M. The needs of patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2008;16:21–29. doi: 10.1002/erv.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover M., Naumann U., Mohammad-Dar L., Glennon D., Ringwood S., Eisler I. A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based cognitive-behavioural skills package for carers of people with anorexia nervosa. Psychol. Med. 2011;41:2581–2591. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh R., Treasure J. Investigating the needs of carers in the area of eating disorders: development of the Carers' needs assessment measure (CaNAM) Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2003;11(2):125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher R.L., Gillaspy J.A. Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychother. Res. 2006;16:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs R., Rhind C., Leppanen J., Treasure J. Interventions for caregivers of someone with an eating disorder: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014;48(4):349–361. doi: 10.1002/eat.22298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs R., Rhind C., Salerno L., Lo Coco G., Goddard E., Schmidt U. Development and validation of a scale to measure caregiver skills in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015;48(3):290–297. doi: 10.1002/eat.22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A., Tuschen-Caffier B. Verlag für Psychotherapie; Münster: 2006. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: Deutschsprachige Übersetzung. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle D., Slater J., Williams C., Schmidt U., Wade T.D. Evaluation of a web-based skills intervention for carers of people with anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013;46(6):634–638. doi: 10.1002/eat.22144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John O.P., Donahue E.M., Kentle R.L. University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research; Berkeley, CA: 1991. The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4a and 54. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce J., Leese M., Szmukler G. The experience of caregiving inventory: further evidence. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2000;35:185–189. doi: 10.1007/s001270050202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamerling V., Smith G. The carers' perspective. In: Treasure J., Schmidt U., Macdonald P., editors. The Clinician's Guide to Collaborative Caring in Eating Disorders: The New Maudsley Method. Routledge; East Sussex: 2010. pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002;32:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou O., Treasure J., Schmidt U. Understanding how parents cope with living with someone with anorexia nervosa: modelling the factors that are associated with carer distress. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008;41(3):233–242. doi: 10.1002/eat.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B., Spitzer R.L., Zipfel S., Herzog W. 2. Auflage. Pfizer; Karlsruhe: 2002. Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ D). Komplettversion und Kurzform. Testmappe mit Manual, Fragebögen, Schablonen. [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B., Decker O., Müller S., Brähler E., Schellberg D., Herzog W. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care. 2008;46:266–274. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Pradas C., Navarro J., Blas L., Steven R., Grau A., Obiols J.E. Further development of a scale of perceived expressed emotion and its evaluation in a sample of patients with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(2):291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Schulz K.F., Altman D.G. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2001;1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond J.M., Hay P.J., Rodgers B., Owen C., Beumont P.V.J. Validity of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004;42:551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical and Health Care Excellence Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment (Nice Guideline NG69) 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69 [PubMed]

- Rammstedt B., John O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. J. Res. Pers. 2007;41:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J.R.J., Elsworth G., Iezzi A., Khan M.A., Mihalopoulos C., Schweitzer I., Herrman H. Monash University, Melbourne; Centre for Health Economics: 2011. Increasing the Sensitivity of the AQoL Inventory for the Evaluation of Interventions Affecting Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J., Iezzi A., Khan M.A., Maxwell A. Validity and reliability of the assessment of quality of life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient. 2014;7(1):85–96. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E., Titov N., Andrews G., McIntyre K., Schwencke G., Solley K. Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One. 2010;5(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. [Google Scholar]

- Roth M., Decker O., Herzberg P.Y., Brahler E. Dimensionality and norms of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in a German general population sample. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2008;24(3):190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi A.J., Haas G.L., Anderson C.M., Newhill C.E., Spring M.B., Ganguli R., Gardner W.B., Rosenstock J.B. A clinical trial to test the feasibility of a telehealth psychoeducational intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their families: intervention and 3-month findings. Rehab. Psychol. 2005;50(4):325–336. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.50.4.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R., Tetzlaff A., Hilbert A. Validity of the brief dyadic scale of expressed emotion in adolescents. Compr. Psychiatry. 2016;66:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda A.R., Whitney J., Hankins M., Treasure J. Development and validation of an eating disorders symptom impact scale (EDSIS) for carers of people with eating disorders. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda A.R., Kyriacou O., Treasure J. Development and validation of the accommodation and enabling scale for eating disorders (AESED) for caregivers in eating disorders. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009;9(1):171. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L. 2017. Internet-Based Interventions for Carers of Individuals with Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders and Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. (Manuscript in Preparation) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stjernswärd S., Hansson L. Effectiveness and usability of a web-based mindfulness intervention for families living with mental illness. Mindfulness. 2017;8:751–764. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stjernswärd S., Hansson L. Outcome of a web-based mindfulness intervention for families living with mental illness–a feasibility study. Informatics for Health and Social Care. 2017;42(1):97–108. doi: 10.1080/17538157.2016.1177533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmukler G.I., Burgess P., Herrman H., Bloch S., Benson A., Colusa S. Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the experience of caregiving inventory. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1996;31(3–4):137–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00785760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J., Schmidt U. Ready, willing and able to change: motivational aspects of the assessment and treatment of eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2001;9(1):4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J., Murphy T., Szmukler T., Todd G., Gavan K., Joyce J. The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: a comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2001;36:343–347. doi: 10.1007/s001270170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J., Whitaker W., Whitney J., Schmidt U. Working with families of adults with anorexia nervosa. J. Fam. Ther. 2005;27(2):158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Voluse A.C., Gioia C.J., Sobell L.C., Dum M., Sobell M.B., Simco E.R. Psychometric properties of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) with substance abusers in outpatient and residential treatment. Addict. Behav. 2011;37:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney J., Murray J., Gavan K., Todd G., Whitaker W., Treasure J. Experience of caring for someone with anorexia nervosa: qualitative study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:444–449. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmers F., Munder T., Leonhart R., Herzog T., Plassmann R., Barth J. Die deutschsprachige Version des Working Alliance Inventory - short revised (WAI-SR) - Ein schulenübergreifendes, ökonomisches und empirisch validiertes Instrument zur Erfassung der therapeutischen Allianz. Klinische Diagnostik und Evaluation. 2008;1(3):343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Winn S., Perkins S., Walwyn R., Schmidt U., Eisler I., Treasure J. Predictors of mental health problems and negative caregiving experiences in carers of adolescents with bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007;40(2):171–178. doi: 10.1002/eat.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst F.M., Rumpf H.J., Skipper G.E., Allen J.P., Kunz I., Beschoner P. Estimating the prevalence of drinking problems among physicians. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):561–564. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabala M.J., MacDonald P., Treasure J. Appraisal of caregiving burden, expressed emotion and psychological distress in families of people with eating disorders: a systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2009;17:338–349. doi: 10.1002/erv.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]