Abstract

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic, inflammatory connective tissue disorder characterized by symmetrical proximal myopathy and characteristic skin involvement. The pathogenesis of DM is widely debated; however, it is postulated to be an end result of immune-mediated cascade, triggered by multiple environmental factors in a genetically predisposed individual. In addition to underlying malignancies, many drugs have been reported to be associated with DM. Capecitabine is a chemotherapeutic agent, approved by the United States-Food and Drug Administration for the management of colonic, metastatic colonic, and metastatic breast carcinoma. It is converted into 5-fluorouracil after oral intake. Common dose-limiting toxicities associated with the usage of the capecitabine include increased bilirubin levels, diarrhea, and hand-foot syndrome. DM-induced by capecitabine has rarely been reported. Herein, we describe a patient of metastatic carcinoma breast, who developed DM after capecitabine intake. The patient had accidental re-challenge with capecitabine resulting in the reappearance of the cutaneous and musculoskeletal system, thereby confirming our diagnosis of drug-induced DM in the setting of underlying malignancy.

Keywords: Breast carcinoma, capecitabine, dermatomyositis

Introduction

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a rare autoimmune disorder affecting skin and skeletal muscles. The disease was first recognized in the 19th century by Wagner, Hepp, and Unverricht. The term “dermatomyositis” was coined by Unverricht in 1891. It is characterized by clinically progressive and symmetrical involvement of proximal muscles and characteristic cutaneous involvement such as heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, dystrophic cuticles, Gottron's papules over digits, and erythema over knees and elbows.[1] Muscle involvement manifests as proximal muscle weakness to begin with, either with myalgias or without it. DM has an estimated incidence of about 1/100,000 cases worldwide.[2] Despite significant advancements in the understanding of DM, its etiopathogenesis is still debated. However, drugs and malignancies have been reported to be important associations of DM. The initial set of diagnostic and classification criteria for DM was suggested by Bohan and Peter in 1975, which includes characteristic cutaneous features, progressive symmetrical weakness of muscles, elevated muscle enzymes, abnormal electromyogram, and an abnormal muscle biopsy finding. The diagnosis was considered definite, probable, and possible when the skin rash is associated with 3, 2, or 1 muscle criteria, respectively.[3]

Drug-induced DM was first reported by Beickert and Kuhne in 1960 in a patient on chlorpromazine therapy.[4] Since then several studies have reported the onset or exacerbation of DM due to drugs. Hydroxyurea is by far the most common drug reported to induce DM, mostly in cases of chronic myeloid leukemia.[5] In most of the cases, it becomes difficult to prove drug causality because of multiple drug therapy and underlying disease. Any patient who develops typical clinical appearance, muscle involvement and has elevated creatinine kinase following intake of the drug, should undergo electromyogram or magnetic reasonance imaging (MRI) of muscles involved, muscle and skin biopsy to rule out the development of drug-induced DM.[1] Apart from hydroxyurea, several categories of drugs including, anti-neoplastic agents, lipid-lowering agents, biologics such as anti-tumor necrosis factor, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antifungals, and vaccines have been incriminated in causing drug-induced DM.[6,7] This increase in the reported cases of drug induced DM is because of a better understanding of its myriad atypical clinical presentation, a high degree of clinical suspicion among the physicians and a better understanding of the cutaneous adverse effects of chemotherapeutic agents.

Case Report

A 45-year-old female, a case of metastatic carcinoma right breast diagnosed in October 2016, was referred to the dermatology OPD with complaints of swelling around eyes and lips of 2- week duration. She gave a history of intake of tablet lapatinib and capecitabine 1 week before the onset of swelling. She had previously received six cycles of injection adriamycin 85 mg and injection cyclophosphamide 800 mg at 3 weekly intervals with no adverse effects. However, while on injection adriamycin and injection cyclophosphamide, she developed pulmonary metastasis. Hence, her therapy was switched over to lapatinib 1.5 g once a day and capecitabine 1 g orally twice daily. For her angioedema, she was admitted to the hospital and was managed with injection hydrocortisone 200 mg intravenous intermittently, to which she did not respond. She was referred to dermatology outpatient department (OPD) for consultation when swelling around her eyes and lips increased even after multiple doses of intravenous hydrocortisone. On examination, her general physical and systemic examination was unremarkable. Dermatological examination revealed swelling around eyes and both lips (upper>lower) [Figure 1a]. There was diffuse violaceous hyperpigmentation around both eyes, forehead, and temple area. Patchy hyperpigmentation was seen on upper back [Figure 1b]. Examination of both the hands and nails was essentially normal.

Figure 1.

(a) The view of periorbital and labial swelling, (b) Patchy hyperpigmentation on back

She also gave a history of difficulty in combing her hair, difficulty in getting up from squatting position and the inability to climb up the stairs after being started on lapatinib and capecitabine. Examination of the musculoskeletal system was done which revealed grade 3/5 power both thighs, legs, arms and forearms in both extensor and flexor group of muscles in both upper and lower limbs. However, she denied history suggestive of dysphagia, dysphonia, dysarthria, or Raynaud's phenomenon.

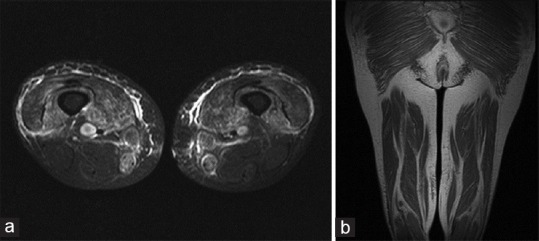

Laboratory findings revealed hemoglobin - 11 g%, TLC - 9600/mm3, CRP - 28, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) - 2050 U/L (Normal = 25–195 U/L), LDH - 756 IU/L (Normal = 200–400 IU/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 82 mm/h, C-reactive protein of 2.1 mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase of 300 IU/L, and aldolase of 29 U/L (Normal 1.0–7.5 U/L). Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique was negative and anti-Jo antibody was not done because the patient could not afford it. She also denied muscle biopsy. MRI both thighs and legs was done which revealed areas of hyper-intense signals involving the subcutaneous tissue and almost all visualized muscles of bilateral thighs and legs with relative sparing of the posterior compartment of thighs on short tau inversion recovery sequences. There was no focal collection visualized in any of the muscles [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

(a) Spin-echo T1, turbo spin echo-fat saturated (FS) T2 and T2 short-tau inversion recovery axial and coronal images of thighs showing areas of hyperintense signals involving subcutaneous tissue and muscles. Visualized bones and neurovascular bundles are normal, (b) Spin-echo T1, turbo spin echo-FS T2 and T2 short-tau inversion recovery axial and coronal images of thighs showing areas of hyperintense signals involving subcutaneous tissue and muscles. Visualized bones and neurovascular bundles are normal

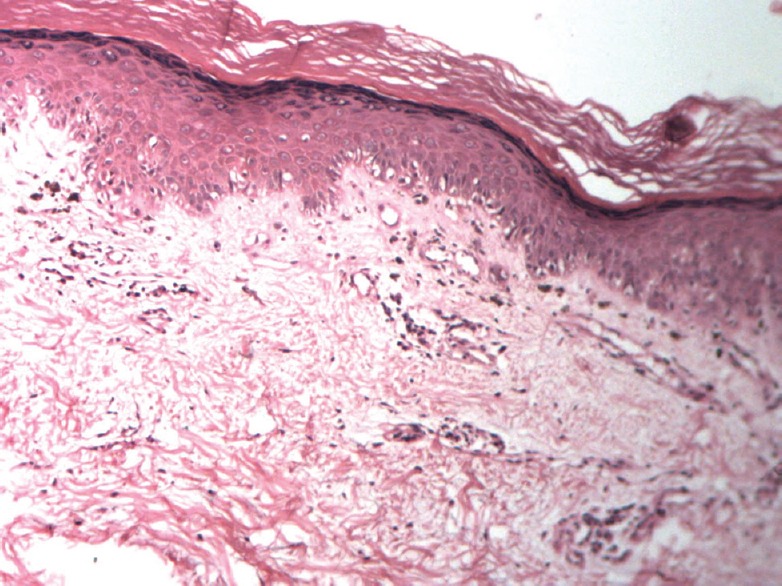

Punch biopsy from the patch on face revealed mild epidermal atrophy with areas of vacuolar alteration of basal keratinocytes. Papillary dermis showed sparse lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate around blood vessels and melanophages. No evidence of mucin was seen in dermis [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Punch biopsy showing irregular atrophy of epidermis, basal cell vacuolation and Perivascular infiltrate

In view of history, clinical features increased muscle enzyme levels, MRI findings and a skin biopsy report consistent with DM, a diagnosis of DM, likely due to the drug was made. Lapatinib and Capecitabine were stopped and she was started on tablet prednisolone 50 mg once a day. Within 2 days of starting prednisolone, edema around her lips and eyes started subsiding, weakness of the muscles also gradually reduced. Serial CPK level showed consistent decline and came down to the level of 110 U/L after 4 weeks of stopping the drugs. The patient was discharged from the hospital.

A month later patient herself restarted capecitabine as she could not come for her oncology review. She denied taking lapatinib as it was not available with her. Four days later, she again developed periorbital and labial swelling along with difficulty in ambulating and combing her hair. She reported to the Dermatology OPD for the same. Examination revealed swelling around both the eyes and lips. There was diffuse erythema around her eyes and temple region. Power both her upper and lower limbs was 4/5 in both extensors and flexor compartment. She was advised to stop capecitabine immediately. Her CPK was done which was 1696 U/L.

The patient was re-started on prednisolone 60 mg/day. She had significant improvement in a week. At the time of discharge, she was advised not to take Capecitabine on her own and was referred back to the treating Oncologist for further management.

Discussion

DM has a definite association with underlying malignancy. Patients with DM have three- to eight-fold increased risk of developing malignancies as compared to the general population. The most common cancers associated with DM are breast cancer, ovarian cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, pancreatic, stomach, and colorectal cancer. The type of associated malignancies differ in different studies probably because of the different prevalence of certain cancer types in the studied population.[8]

However, because of the increased risk of malignancy in patients with DM, all patients who are diagnosed with DM should undergo a complete evaluation to rule out underlying malignancy and these patients should also be kept under follow-up. It is classified under the broad category of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and has extremely variable presentation, which ranges from predominant skeletal muscle involvement (polymyositis) to only skin involvement without any muscle involvement (amyopathic DM).

Drugs can also cause DM and hydroxyurea is one of the most common drugs causing drug-induced DM. Many other drugs including immune checkpoint inhibitors have also been reported to cause DM.

Drug-induced DM can have variable presentations such as clinical features typical of classical DM, cutaneous DM-like lesions without any involvement of muscles (amyopathic DM), provocation of PM, myalgia/muscle damage, only serum enzyme changes without any symptoms.[6]

These drugs are proposed to promote the process of apoptosis and enhance innate immunity, resulting in autoimmunity. The cellular antigens are displaced leading to a state of neoantigenicity and antibody formation against endothelial cells.[7] Drug-induced DM is generally considered to be benign in nature. In most of the cases, discontinuation of drug along with or without additional treatment is sufficient.[9]

DM-induced by hydroxyurea is different from nonhydroxyurea group of drugs. Time of onset of DM is longer in patients who develop DM due to hydroxyurea as compared to the non hydroxyurea drugs. ANA positivity and muscle weakness is more commonly associated with nonhydroxyurea group of drugs.[10]

Diagnosis of drug-induced DM still remains challenging due to the difficulty in attributing causality to a particular drug in most of the cases because of multiple drugs and underlying malignant and rheumatological disorders. Irrespective of the causative drug, the principle of management of drug-induced DM remains discontinuation of the drug and adding topical or systemic corticosteroid or disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. However, drug-induced DM is rare, and it is not possible to predict the risk of developing it in individual patients.

It is difficult to ascertain the drug causality of DM in the presence of malignancy, as it can also be associated with DM. However, the patient was accidentally re-challenged with capecitabine which resulted in reappearance of DM-like lesions and muscle involvement, which subsided on stopping the drug twice.[11] The proposed mechanism of DM induced by capecitabine is autoantibody production against muscle differentiation and regeneration molecules.[12] As per the WHO-UMC (WHO-Uppsala Monitoring Centre) causality criteria, our case qualifies into “probable” category.[13]

Our objective of reporting this case is to highlight the importance of the high degree of clinical suspicion and a sound knowledge of both typical and atypical presentation associated with capecitabine. Any patient on capecitabine therapy, who presents with cutaneous findings suggestive of DM along with weakness of muscles, should be promptly evaluated for DM.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Callen JP, Wortmann RL. Dermatomyositis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:363–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haroon M, Eltahir A, Harney S. Generalized subcutaneous edema as a rare manifestation of dermatomyositis: Clinical lesson from a rare feature. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:135–7. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318214f1a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis ( first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beickert A, Kuhne W. Dermatomyositis mit immuneleucopenie, phenothiazinschadigung. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1960;90:132–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dacey MJ, Callen JP. Hydroxyurea-induced dermatomyositis-like eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:439–41. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA. Dermatomyositis and drugs. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:187–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4857-7_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Waldman J, Knight D, Seilstad K, Hearne D, et al. Terbinafine-induced dermatomyositis: A case report and literature review of drug-induced dermatomyositis. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang YF, Wu YJ, Kuo CF, Luo SF, Yu KH. Malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: Analysis of 192 patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1977–84. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss KW, Gonzalez-Buritica H, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Polymyositis-dermatomyositis: A clinical review. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:437–43. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.65.765.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seidler AM, Gottlieb AB. Dermatomyositis induced by drug therapy: A review of case reports. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:872–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen FW, Zhou X, Egbert BM, Swetter SM, Sarin KY. Dermatomyositis associated with capecitabine in the setting of malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:e47–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mammen AL. Autoimmune myopathies: Autoantibodies, phenotypes and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:343–54. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Use of the WHO-UMC System for Standardized Case Causality Assessment. [Last accessed on 2010 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.WHO-UMC.org/graphics/4409.pdf .