Abstract

Background

Preterm birth is a major cause of prenatal and postnatal mortality particularly in developing countries. This study investigated the maternal risk factors associated with the risk of preterm birth.

Methods

A population-based case-control study was conducted in several provinces of Iran on 2463 mothers referred to health care centers. Appropriate descriptive and analytical statistical methods were used to evaluate the association between maternal risk factors and the risk of preterm birth. All tests were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The mean gestational age was 31.5 ± 4.03 vs. 38.8 ± 1.06 weeks in the case and control groups, respectively. Multivariate regression analysis showed a statistically significant association between preterm birth and mother’s age and ethnicity. Women of Balooch ethnicity and age ≥ 35 years were significantly more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.01–-2.44 and OR: 9.72; 95% CI: 3.07–30.78, respectively). However, no statistically significant association was observed between preterm birth and mother’s place of residence, level of education, past history of cesarean section, and BMI.

Conclusion

Despite technological advances in the health care system, preterm birth still remains a major concern for health officials. Providing appropriate perinatal health care services as well as raising the awareness of pregnant women, especially for high-risk groups, can reduce the proportion of preventable preterm births.

Keywords: Preterm birth, Risk factor, Case-control, Iran

Introduction

Preterm birth is defined as delivery before the gestational week 37 or day 259 [1–3]. It has been the most concerning complication among pregnant women and affects 10% of all pregnancies. Annually, 1 million neonatal deaths occur due to preterm birth [4]. It constitutes a large proportion of medical expenses and impose enormous economic burden on health care systems, families, and children [1]. Preterm birth is still a prevalent public health issue responsible for high perinatal mortality and long-term morbidity worldwide Despite improved perinatal care programs, it still remains a major leading cause of perinatal mortality, particularly in developing regions [5, 6].

Preterm birth is a multifactorial phenomenon, partially in association with immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors; however, its attributing factors have not yet been well studied [7, 8]. Previous studies concerned with preterm birth indicated that 45–50% of causes are unknown, 30% can be attributed to premature rupture of the membrane, and 15–20% are medical indications such as elective labor [8–10]. Recent studies have suggested that preterm birth is an independent risk factor for future cardiovascular diseases, cardiac ischemic diseases, and stroke [11, 12]. Due to the enormous economic and emotional burden of preterm birth and its associated complications, this study was conducted to examine the association between prenatal risk factors and preterm birth.

Material and methods

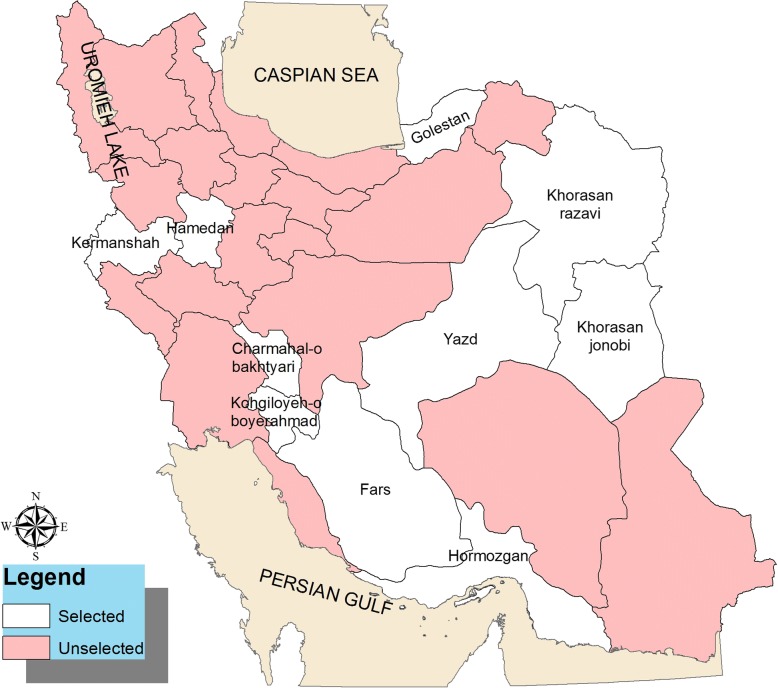

This population-based case-control study was conducted on 2463 mothers, including 668 cases and 1795 controls, referred to a health care center in several provinces of Iran, namely, Fars, Hormozgan, Kermanshah, Hamadan, Kohgiloyeh, and Boyerahmad, Yazd, Southern Khorasan, Golestan, and city of Mashhad (Fig. 1). A rural health care center is a health facility in a village that provides health care for approximately 9000 people of that village and several neighboring villages. Health care providers at a rural health care center include a general physician and public health and midwifery experts. The rural health care center supervises and supports health care facilities in villages and is linked to its superior urban health care center. An urban health care center is a health facility in cities providing care to approximately 12,500 people. Health care providers, including a general physician and public health and midwifery experts, provide laboratory, pharmaceutical, radiological, and medical care in the urban health care centers. Experts at rural and urban health care centers register the provided health care to every family in their health records, such as health care for pregnant women. However, the registered information in the family’s health records were insufficient, and hence we collected additional data through interviews with the study participants.

Fig. 1.

Study project locations in Iran. The population of the study was conducted on mothers that referred to a health care center in several provinces of Iran, including Fars, Hormozgan, Kermanshah, Hamadan, Kohgiloyeh, and Boyerahmad, Yazd, Southern Khorasan, Golestan, and city of Mashhad

The case group was defined as women who had preterm birth in a recent pregnancy, and the control group was defined as women who had full-term birth in a recent pregnancy [13–15]. The sample size ratio in the control and case groups was 3:1. Data were collected through interviews according to a check list containing demographic information (mother’s age, ethnicity, occupation and level of education, place of residence, and consanguineous marriage) and information on the previous pregnancies (the outcome of previous pregnancy, mode of delivery, and interpregnancy interval).

Study subjects were recruited through a multistage cluster sampling method. In the first stage regarding geographical divisions of Iran, nine clusters (provinces) were randomly selected. In the second stage, in each of the nine clusters (provinces), four clusters (cities) were randomly selected from the north, south, east, west, and central areas. In each city, two health care centers (one urban and one rural health care center) were randomly selected. In each health care center, 10 check lists were filled in by well-trained interviewers according to a protocol. In each center, data collection process was conducted simultaneously on the same day for cases and controls. Data of the control group were collected from a random sample of mothers referring to the health care center. If < 10 cases were available in each health care center, the remaining check lists were filled in the nearest center, and if there were > 10 cases, the check lists were filled in for a random sample of mothers. We tried to maintain the same size for the case and control groups.

According to literature review, considering mother’s age > 35 years as a risk factor (p0 = 0.3, p1 = 0.44, z0.95 = 2, z(1-β) = 0.8, design effect = 2) [16] and using the proportion determination formula, the sample size was estimated as 370 for each study group. In this study, the association between preterm birth and 14 independent variables was evaluated. Therefore, taking into account an additional 20 samples for each independent variable, the total sample was calculated as 650 for each study group. The sample size was sufficient considering > 80% power of study.

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic information included mother’s age (age < 35 or ≥ 35 years), place of residence (urban vs. rural area), occupation (housewife/employee/cowhand/farmer/carpet weaver), level of education (illiterate/primary school/intermediate school/high school/academic gradation), ethnicity (Turk/Lor/Arab/Balooch/Torkaman/Fars/Kurd or others), and marriage (consanguineous vs. nonconsanguineous).

Information on the previous pregnancies

This included history of abortion, stillbirth or cesarean section (yes/no), interpregnancy interval (the first pregnancy/< 1 year/1–3 years/> 3 years), BMI (normal/low weight/overweight/obese: grade 1, grade 2, and higher), and cycles of menstruation period (regular/irregular).

The outcome variable

Preterm birth was the outcome variable, which was ascertained through questioning the exact gestational age at the time of birth.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical tests were performed for socio-demographic and pregnancy-related variables. Bivariate analysis was performed to identify the association of dependent and independent variables. Odds ratio was computed to see the strength of association between preterm birth and each of categorical variables. Adjusted odds ratio and their 95% confident interval were calculated by including all exposures with p value < 0.3 in the multivariate model to control for confounding effects [17]. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 19, with two-tailed tests at p ≤ 0.05 level of significance.

Results

This study was conducted on 2463 mothers referred to health care centers (668 cases with a history of preterm birth and 1795 controls without a history of preterm birth). The mean gestational age at the time of birth was 31.5.” 4.03 vs. 38.8 ± 1.06 weeks for the case and control groups, respectively.

Our analysis revealed that 88.8% of cases and 94.0% of controls were 35 years of age. Regarding the ethnicity, 76.8% of cases and 64.1% of controls were Fars. Village dwellers comprised 51.9% of cases and 60.3% of controls. Regarding previous pregnancies, 5.8% of controls reported a history of stillbirth, 12.9% of cases and 11.4% of controls reported a history of cesarean section, and 15.3% of cases and 8.6% of controls had a history of abortion. Birth interval was longer than 3 years in 28.9% of cases and 30.4% of controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information and other characteristics of Mothers in cases and control groups (categorical variables)

| Items | Preterm delivery | Total N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control N (%) |

Case N (%) |

||

| All participants | 1795 (73.0) | 668 (27.0) | |

| Age(years) | |||

| < 35 | 1674 (94.0) | 588 (88.8) | 2262 (92.6) |

| ≥ 35 | 107 (6.0) | 74 (11.2) | 181 (7.4) |

| Level of Education | |||

| Illiterate | 76 (4.2) | 39 (5.9) | 115 (4.7) |

| Primary | 366 (20.4) | 172 (25.8) | 538 (21.9) |

| Guidance | 449 (25.0) | 126 (18.9) | 575 (23.4) |

| High school | 689 (38.4) | 251 (37.7) | 940 (38.2) |

| Collegiate | 213 (11.9) | 78 (11.7) | 291 (11.8) |

| Ethnic | |||

| Tork | 366 (21.7) | 38 (6.1) | 404 (17.5) |

| Lor | 73 (4.3) | 37 (5.9) | 110 (4.8) |

| Fars | 1083 (64.1) | 479 (76.8) | 1562 (67.5) |

| Kord | 29 (1.7) | 23 (3.7) | 52 (2.2) |

| Arab | 20 (1.2) | 6 (1.0) | 26 (1.1) |

| Balooch | 11 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) | 17 (0.7) |

| Torkaman | 99 (5.9) | 32 (5.1) | 131 (5.7) |

| Else | 9 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) | 12 (0.5) |

| Occupation | |||

| Housewife | 1610 (90.9) | 610 (91.9) | 2220 (91.2) |

| Employee | 110 (6.2) | 40 (6.0) | 150 (6.2) |

| Farmer& carpet weaver | 31 (1.8) | 7 (1.1) | 38 (1.6) |

| Other | 20 (1.1) | 7 (1.1) | 27 (1.1) |

| Place of Residence | |||

| Urban | 694 (39.7) | 314 (48.1) | 1008 (42.0) |

| Rural | 1053 (60.3) | 339 (51.9) | 1392 (58.0) |

| Abortion history | |||

| Yes | 154 (8.6) | 102 (15.3) | 256 (10.4) |

| No | 1641 (91.4) | 566 (84.7) | 2207 (89.6) |

| Stillbirth history | |||

| Yes | 104 (5.8) | 122 (18.3) | 226 (9.2) |

| No | 1691 (94.2) | 546 (81.7) | 2237 (90.8) |

| Cesarean history | |||

| Yes | 205 (11.4) | 86 (12.9) | 291 (11.8) |

| No | 1590 (88.6) | 582 (87.1) | 2172 (88.2) |

| Gap pregnancy(years) | |||

| Upper than 3 | 537 (30.4) | 189 (28.9) | 726 (30.0) |

| Lower than 1 | 74 (4.2) | 55 (8.4) | 129 (5.3) |

| 1–3 | 496 (28.1) | 153 (23.4) | 649 (26.8) |

| Primary pregnancy | 661 (37.4) | 257 (39.3) | 918 (37.9) |

| Consanguineous marriage | |||

| Yes | 494 (28.1) | 205 (31.3) | 699 (29.0) |

| No | 1263 (71.9) | 450 (68.7) | 1713 (71.0) |

| Supplements Consumption | |||

| Yes, use regular | 1449 (81.8) | 535 (80.5) | 1984 (81.4) |

| Yes, use not regular | 213 (12.0) | 91 (13.7) | 304 (12.5) |

| Use not | 109 (6.2) | 39 (5.9) | 148 (6.1) |

| BMI | |||

| Normal | 893 (53.6) | 292 (48.7) | 1185 (52.3) |

| Underweight | 313 (18.8) | 126 (21.0) | 439 (19.4) |

| Overweight | 329 (19.7) | 121 (20.2) | 450 (19.9) |

| Obesity grade1 | 101 (6.1) | 55 (9.2) | 156 (6.9) |

| Obesity grade 2 | 31 (1.9) | 5 (0.8) | 36 (1.6) |

| Regular Cycles of period | |||

| Yes | 1564 (90.2) | 536 (82.7) | 2100 (88.2) |

| No | 170 (9.8) | 112 (17.3) | 282 (11.8) |

Mothers with a consanguineous marriage were 1.32 times more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.04–1.67), those with a history of abortion were 1.57 times more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.08–2.27), and those with a history of stillbirth were approximately 4 times more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 3.92; 95% CI: 2.76–5.57) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regression of risk factors for preterm delivery

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of Residence | |||

| Rural | – | – | – |

| Urban | 1.40 | 1.17–1.68 | 0.001 |

| Level of Education | |||

| Collegiate | – | – | – |

| Illiterate | 1.40 | 0.88–2.23 | 0.155 |

| Primary | 1.28 | 0.93–1.76 | 0.122 |

| Guidance | 0.76 | 0.55–1.06 | 0.110 |

| High school | 0.99 | 0.73–1.33 | 0.973 |

| Consanguineous marriage | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.16 | 0.95–1.41 | 0.126 |

| Abortion history | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.92 | 1.46–2.51 | 0.001 |

| Stillbirth history | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 3.63 | 2.74–4.80 | 0.001 |

| Cesarean history | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.87–1.50 | 0.321 |

| BMI | |||

| Normal | – | – | – |

| Underweight | 1.23 | 0.96–1.57 | 0.097 |

| Overweight | 1.12 | 0.87–1.44 | 0.350 |

| Obesity grade1 | 1.66 | 1.16–2.37 | 0.005 |

| Obesity grade 2 | 0.49 | 0.19–1.28 | 0.146 |

| Age(years) | |||

| < 35 | – | – | – |

| ≥ 35 | 1.96 | 1.44–2.68 | 0.001 |

| Ethnic | |||

| Tork | – | – | – |

| Lor | 4.88 | 2.90–8.19 | 0.001 |

| Fars | 4.26 | 2.99–6.05 | 0.001 |

| Kord | 7.63 | 4.02–14.50 | 0.001 |

| Arab | 2.88 | 1.09–7.63 | 0.389 |

| Balooch | 5.24 | 1.84–15.0 | 0.001 |

| Torkaman | 3.11 | 1.85–5.23 | 0.001 |

| Else | 3.21 | 0.83–12.36 | 0.081 |

| Regular Cycles of period | |||

| Yes | – | – | – |

| No | 1.92 | 1.48–2.48 | 0.001 |

| Gap pregnancy(years) | |||

| Upper than 3 | – | – | – |

| Lower than 1 | 2.11 | 1.43–3.10 | 0.001 |

| 1–3 | 0.87 | 0.68–1.12 | 0.293 |

| Primary pregnancy | 1.10 | 0.88–1.37 | 0.374 |

Mothers aged 35 years or more compared to those younger than 35 years were 1.64 times more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.01–2.44). Regarding ethnicity, Balooch mothers compared to Turkish mothers were 9.27 times more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 9.72; 95% CI: 3.07–30.78). Mothers with irregular cycles of menstruation period compared to those with regular cycles were 1.77 times more likely to develop preterm birth (OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.14–3.01). Regarding the interpregnancy interval, mothers with < 1-year interpregnancy interval compared to those with > 3 years were 1.85 times more liable to develop preterm birth (OR: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.14–3.01). However, no statistically significant association was observed regarding mother’s place of residence, level of education, supplement consumption, history of cesarean section, and BMI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model of risk factors for preterm delivery

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | |||

| < 35 | – | – | – |

| ≥ 35 | 1.64 | 1.01–2.44 | 0.015 |

| Ethnic | |||

| Tork | – | – | – |

| Lor | 4.55 | 2.50–8.29 | 0.001 |

| Fars | 4.07 | 2.72–6.09 | 0.001 |

| Kord | 5.80 | 2.74–12.28 | 0.001 |

| Arab | 1.71 | 0.50–5.80 | 0.484 |

| Balooch | 9.72 | 3.07–30.78 | 0.001 |

| Torkaman | 3.25 | 1.77–5.97 | 0.001 |

| Else | 3.69 | 0.85–16.09 | 0.108 |

| Regular Cycles of period | |||

| Yes | – | – | – |

| No | 1.77 | 1.14–3.01 | 0.001 |

| Gap pregnancy(years) | |||

| Upper than 3 | – | – | – |

| Lower than 1 | 1.85 | 1.14–3.01 | 0.012 |

| 1–3 | 0.81 | 0.60–1.11 | 0.198 |

| Primary pregnancy | 1.43 | 1.08–1.88 | 0.011 |

| Consanguineous marriage | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.32 | 1.04–1.67 | 0.019 |

| Abortion history | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.57 | 1.08–2.27 | 0.016 |

| Stillbirth history | |||

| No | – | – | – |

| Yes | 3.92 | 2.76–5.57 | 0.001 |

Discussion

The etiology of preterm birth has been a major concern in obstetrics worldwide. The cause of 50% of preterm births is unknown [18]. However, this study revealed a strong association between preterm birth and a history of abortion and stillbirth, ethnicity, interpregnancy interval, cycles of menstruation period, and consanguineous marriage. Consistent with other studies in this area, our study suggests an increased risk of preterm birth for mothers older than 35 years [18–22]. Martin et al. found an increased risk of preterm birth associated with older ages in women of high economic status [23]. The majority of studies indicated that the increased risk of preterm birth associated with increasing mother’s age may be confounded by socioeconomic factors or health complications associated with older ages, namely, hypertension, and renal diseases. Preventive strategies for older age mothers include providing appropriate health education and consultation, regular perinatal care during pregnancy, and encouraging mothers toward seeking effective family health [11, 22, 24]. Along with other studies, our study results suggest an association between preterm birth and ethnicity [4, 13, 15, 25]. Among all the studied ethnic groups, Balooch ethnicity was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth. This increased risk can be attributed to low socioeconomic status, high reproductive rates, low reproductive health status, insufficient reproductive knowledge, and poor nutrition. Preterm birth is affected by differences in ethnic groups regarding parents’ level of education, tobacco use, distress, and unfavorable experiences in life [13, 14, 26].

We observed an increased risk of preterm birth associated with consanguineous marriage, which was consistent with the results of other studies examining the genetic risk factors [27]. In addition, it should be considered that preterm birth can be affected by different environmental factors as well. Several studies suggested that even in the absence of genetic factors, preterm birth is associated with environmental factors such as socioeconomic status and tobacco use [27, 28]. Moreover, a number of studies suggested an interaction between preterm birth and parental genes or inheritance of human leukocyte antigen [29, 30].

Consistent with other studies, the present study demonstrated that a history of abortion and stillbirth is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth. Recent studies suggested an association between history of abortion and increased risk of preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies [11, 18, 31]. In addition, three large, population-based historical cohort studies and two large, case-control studies suggested that a history of abortion is a risk factor for preterm birth [31–33]. Several studies found an increased risk of preterm birth in association with more abortions and also indicated that various genetic and environmental factors can lead to repeated abortions [34–36]. It was also observed that abortion as the result of the last pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth in gestational weeks < 32. The strength of this association decreases with increasing gestational weeks [31]. Although we observed an association between preterm birth and history of abortion, a population-based study in Pakistan reported conflicting results. Such inconsistent results can be attributed to the differences in the methods or limitations such as using data extracted from registry systems, lack of a control group, different definitions of gestational weeks for abortion, lack of control on potential biases, and confounding effects [31, 37].

We found that mothers with irregular cycles of menstruation period compared to those with regular cycles were more likely to develop preterm birth. Bonessen et al. also showed that regular cycles of menstruation period are associated with lower risk of prolonged pregnancy. In women with regular cycles of menstruation, the exact gestational age is clear and health care providers are not concerned with induction of pain [38].

Consistent with the results of other studies, our study results suggest an increased risk of preterm birth in mothers with < 1-year interpregnancy interval [39, 40]. Adams et al. suggested an increased risk of preterm birth associated with a 6- to 11-month interpregnancy interval. This risk decreased for interpregnancy intervals of > 47 months [41]. Krymko et al. [39] suggested that this association can be attributed to the presence of intrauterine infections before pregnancy or acute infections during pregnancy, mother’s physical weakness, emotional status, hormone secretion due to distress, or uterus contractions.

Conclusion

Preterm birth is a multifactorial issue in obstetrics. Despite technological improvements in the health care system, it still remains a major concern for health officials. In the present study, ethnicity, history of abortion and stillbirth, irregular cycles of menstruation period, consanguineous marriage, and narrow interpregnancy intervals were found to be risk factors for preterm birth. Regarding preventive strategies, it is recommended that mothers be provided with reproductive health care before and during pregnancy, particularly in the high-risk groups, to reduce the proportion of preventable cases of preterm birth.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The large sample size of the present study selected from several provinces includes different ethnic groups and socioeconomic status and increases the generalizability of results to the general population. In addition, data were collected by well-trained interviewers according to a predetermined protocol. However, the results of the present study should be interpreted with caution due to potentially uncontrolled confounding effects, recall bias related to history of abortion, and reporting bias due to self-report nature of data collection method. In addition, the time interval between the last abortion and current pregnancy was not recorded in the mother’s profile.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Research Center for Health Sciences of Shiraz and Hormozgan Universities of Medical Sciences, research affairs, and other renowned Universities that participated in this project and provided their services with dedication.

Funding

The project was approved and financially supported by the Vice Chancellor of Research in Shiraz and Hormozgan Universities of Medical Sciences with registration numbers (No. 93–01-42-8964) and (No. 94112), respectively.

Availability of data and materials

The data set collected and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

Authors’ contributions

MS and TV (data acquisition, drafting the manuscripts in Persian and revising the manuscripts in English), HRT (Designing project and supervision), ShS (data acquisition, quality control of data in Khorasan Razavi province), ME (data acquisition and revising the manuscripts in English), HY (data acquisition, quality control of data in Hormozgan province), EM (data acquisition, focal point of data gathering in Hamadan province), AR(designing project in statistical analysis section, data analysis and prepare of results), AGh (data acquisition, focal point of data gathering in southern Khorasan province), NK (data acquisition, focal point of data gathering in Yazd province), ME (data acquisition, data entry and quality control), AN (data acquisition, focal point of data gathering in Golestan province), SAH (data acquisition, focal point of data gathering in Fars province), FZ(data acquisition, focal point of data gathering in Hormozgan province), SM(data acquisition, quality control of data in Yazd province), KE(Designing project and supervision), AT(Designing project and provided financial support to generate copies of questionnaires, interviewing costs, and transportation costs for interviewer’s team during the data collection procedure), CS(data acquisition, checking quality of final data), MH (data analysis, prepare of tables). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by Shiraz university of Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Ir.sums.rec.1394.f330). All participants provided written informed consent prior to interview; this included permission to use anonymised quotations in publications.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Deryabina EG, et al. Perinatal outcome in pregnancies complicated with gestational diabetes mellitus and very preterm birth: case-control study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(sup2):52–55. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2016.1232215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plunkett J, et al. Population-based estimate of sibling risk for preterm birth, preterm premature rupture of membranes, placental abruption and pre-eclampsia. BMC Genet. 2008;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C, et al. Subgroup identification of early preterm birth (ePTB): informing a future prospective enrichment clinical trial design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1189-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubens CE, et al. Prevention of preterm birth: harnessing science to address the global epidemic. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(262):262sr5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer MS, et al. Secular trends in preterm birth: a hospital-based cohort study. JAMA. 1998;280(21):1849–1854. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero R, et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck S, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(1):31–38. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villar J, et al. The preterm birth syndrome: a prototype phenotypic classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedderson MM, Ferrara A, Sacks DA. Gestational diabetes mellitus and lesser degrees of pregnancy hyperglycemia: association with increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):850–856. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu Hamad K, Abed Y, Abu Hamad B. Risk factors associated with preterm birth in the Gaza strip: hospital-based case-control study. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13(5):1132–1141. doi: 10.26719/2007.13.5.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang F, et al. Preterm births in Peking union medical College Hospital in the Past 25 years. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2016;38(5):528–533. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dole N, et al. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and white women in Central North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1358–1365. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustillo S, et al. Self-reported experiences of racial discrimination and black-white differences in preterm and low-birthweight deliveries: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2125–2131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg L, et al. Perceptions of racial discrimination and the risk of preterm birth. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):646–652. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajian-Tilaki K, Esmaielzadeh S, Sadeghian G. Trend of stillbirth rates and the associated risk factors in Babol, northern Iran. Oman Med J. 2014;29(1):18–23. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M, Pryor E. Logistic regression: a self-learning text. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baskaradoss JK, Geevarghese A, Kutty VR. Maternal periodontal status and preterm delivery: a hospital based case-control study. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46(5):542–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lepercq J, et al. Factors associated with preterm delivery in women with type 1 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2824–2828. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butali A, et al. Characteristics and risk factors of preterm births in a tertiary center in Lagos, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:1. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.1.8382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newburn-Cook CV, Onyskiw JE. Is older maternal age a risk factor for preterm birth and fetal growth restriction? A systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(9):852–875. doi: 10.1080/07399330500230912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira LL, et al. Maternal and neonatal factors related to prematurity. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2016;50(3):382–389. doi: 10.1590/S0080-623420160000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martins Mda G, et al. Association of pregnancy in adolescence and prematurity. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2011;33(11):354–360. doi: 10.1590/S0100-72032011001100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witt WP, et al. Preterm birth in the United States: the impact of stressful life events prior to conception and maternal age. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 1):S73–S80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richman LS, et al. Discrimination, dispositions, and cardiovascular responses to stress. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):675–683. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dominguez TP, et al. Racial differences in birth outcomes: the role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):194–203. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svensson AC, et al. Maternal effects for preterm birth: a genetic epidemiologic study of 630,000 families. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1365–1372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ananth CV, et al. Recurrence of spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(3):643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cnattingius S, et al. Maternal and fetal genetic factors account for most of familial aggregation of preeclampsia: a population-based Swedish cohort study. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130a(4):365–371. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li DK, et al. Transmission of parentally shared human leukocyte antigen alleles and the risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):594–600. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000130067.27022.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winer N, et al. Is induced abortion with misoprostol a risk factor for late abortion or preterm delivery in subsequent pregnancies? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ancel PY, et al. History of induced abortion as a risk factor for preterm birth in European countries: results of the EUROPOP survey. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(3):734–740. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreau C, et al. Previous induced abortions and the risk of very preterm delivery: results of the EPIPAGE study. BJOG. 2005;112(4):430–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henriet L, Kaminski M. Impact of induced abortions on subsequent pregnancy outcome: the 1995 French national perinatal survey. BJOG. 2001;108(10):1036–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mannem S, Chava VK. The relationship between maternal periodontitis and preterm low birth weight: a case-control study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2011;2(2):88. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.83067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davenport ES, et al. Maternal periodontal disease and preterm low birthweight: case-control study. J Dent Res. 2002;81(5):313–318. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Induced abortion: not an independent risk factor for pregnancy outcome, but a challenge for health counseling. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(8):587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnesen B, et al. Women with minor menstrual irregularities have increased risk of preeclampsia and low birthweight in spontaneous pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(1):88–92. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krymko H, et al. Risk factors for recurrent preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113(2):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cnattingius S, et al. The influence of gestational age and smoking habits on the risk of subsequent preterm deliveries. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(13):943–948. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisk NM, Fordham K, Abramsky L. Elective late fetal karyotyping. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103(5):468–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data set collected and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.