Abstract

Context

Glucocorticoids regulate energy balance, in part by stimulating the orexigenic neuropeptide agouti-related protein (AgRP). AgRP neurons express glucocorticoid receptors, and glucocorticoids have been shown to stimulate AgRP gene expression in rodents.

Objective

We sought to determine whether there is a relationship between plasma AgRP and hypothalamic AgRP in rats and to evaluate the relationship between cortisol and plasma AgRP in humans.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated plasma AgRP levels prior to transsphenoidal surgery in 31 patients with Cushing disease (CD) vs 31 sex- and body mass index–matched controls from a separate study. We then prospectively measured plasma AgRP, before and 6 to 12 months after surgery, in a subgroup of 13 patients with CD. Plasma and hypothalamic AgRP were measured in adrenalectomized rats with and without corticosterone replacement.

Results

Plasma AgRP was stimulated by corticosterone in rats and correlated with hypothalamic AgRP expression. Plasma AgRP levels were higher in patients with CD than in controls (139 ± 12.3 vs 54.2 ± 3.1 pg/mL; P < 0.0001). Among patients with CD, mean 24-hour urine free cortisol (UFC) levels were 257 ± 39 μg/24 hours. Strong positive correlations were observed between plasma AgRP and UFC (r = 0.76; P < 0.0001). In 11 of 13 patients demonstrating surgical cure, AgRP decreased from 126 ± 20.6 to 62.5 ± 8.0 pg/mL (P < 0.05) postoperatively, in parallel with a decline in UFC.

Conclusions

Plasma AgRP levels are elevated in CD, are tightly correlated with cortisol concentrations, and decline with surgical cure. These data support the regulation of AgRP by glucocorticoids in humans. AgRP’s role as a potential biomarker and as a mediator of the adverse metabolic consequences of CD deserves further study.

Plasma AgRP levels are elevated in CD, are strongly correlated with cortisol concentrations, and decline following curative transsphenoidal surgery.

Glucocorticoids are key regulators of energy balance and metabolism. Although they have been shown to directly affect peripheral tissues, glucocorticoids also regulate energy balance through central mechanisms (1). This occurs, in part, at the level of the hypothalamic melanocortin system. Situated in the arcuate nucleus, the melanocortin system consists of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons and downstream neuronal targets that express melanocortin-3 and -4 receptors (2–4). The POMC-derived anorexigenic peptide α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) inhibits food intake and stimulates energy expenditure, whereas the orexigenic neuropeptide AgRP acts as a melanocortin antagonist, stimulating appetite and inhibiting energy expenditure by inhibiting the effects of α-MSH at melanocortin receptors (2). POMC and AgRP neurons are responsive to several peripheral metabolic signals that influence energy balance. In the hypothalamus, AgRP gene expression is suppressed by peripheral hormonal signals, including leptin and insulin (5–8). In animals, glucocorticoids modulate the synthesis and release of AgRP (9–11). AgRP neurons express glucocorticoid receptors (12) and glucocorticoid response elements have been identified within the AgRP promotor region (13). In rodents, glucocorticoids stimulate hypothalamic AgRP expression (9, 11, 14), and AgRP increases in response to low- and high-dose glucocorticoids and following acute and long-term glucocorticoid administration (9, 15, 16). In comparison, AgRP mRNA expression in the medial basal hypothalamus declines following adrenalectomy (9, 17), a change reversed by corticosterone replacement (9, 18). Notably, the fall in AgRP mRNA with adrenalectomy occurs despite a concomitant decrease in leptin and insulin, which would ordinarily stimulate AgRP expression.

In humans, studies examining the impact of glucocorticoids on the hypothalamic regulation of energy balance and metabolism were previously limited by the dearth of peripheral biomarkers of brain melanocortin activity. In rodents, plasma and hypothalamic AgRP concentrations are correlated (19), and recent data suggest that plasma AgRP may be a marker of hypothalamic AgRP in humans as well (20–22). We have demonstrated a correlation between plasma AgRP and adiposity in weight-stable humans (21). We have also shown that plasma AgRP levels increase with fasting and fall with refeeding, paralleling expected changes in hypothalamic AgRP under these conditions and supporting the use of plasma AgRP as a marker of hypothalamic AgRP in humans (22). Given the substantial impact of glucocorticoids on AgRP and energy balance in rodents, we sought to examine the relationship between plasma AgRP and cortisol levels in Cushing disease (CD), a state of chronic glucocorticoid excess.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Study participants were 31 patients (26 women and 5 men) with ACTH-dependent CD aged 19-72 years, recruited from the Neuroendocrine Unit at Columbia University, and 31 healthy controls, matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) (Table 1). All patients with CD had active hypercortisolism at the time of enrollment, documented by at least two elevated 24-hour urine free cortisol (UFC) concentrations and late-night salivary cortisol measurements, and plasma ACTH levels >15 pg/mL. The diagnosis of CD was subsequently confirmed by surgical pathology, surgical cure, and/or inferior petrosal sinus sampling demonstrating a central to peripheral ACTH gradient of ≥2:1 before stimulation with CRH or desmopressin, or ≥3:1 following stimulation (23–25). Healthy controls were screened by medical history before participation and were free from past or present renal, hepatic, neurologic, and psychiatric disorders. All were nonsmokers, had no history of substantial alcohol intake, had a stable weight for at least 6 months, and were not taking medications other than multivitamins. Premenopausal female controls had regular 25- to 35-day menstrual cycles.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Variable | Patients With CD (n = 31) | Controls (n = 31) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 5 (16) | 5 (16) | NS |

| Women, n (%) | 26 (84) | 26 (84) | NS |

| Age, y | 42.0 ± 2.6 | 37.7 ± 1.6 | 0.062 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 34.2 ± 1.3 | 33.7 ± 1.3 | NS |

| Cortisol, μg/dL | 25.6 ± 2.3 | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 0.0001 |

| 24-h UFC, μg/d | 257 ± 39 | NA | NA |

Unless otherwise noted, data are reported as mean ± SEM. NA, not applicable; NS, not significant.

The Columbia University Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all participants provided appropriate written informed consent.

Protocol

Rodent studies

All animal experiments were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animal studies were carried out previously and the effects of adrenalectomy (ADX) and corticosterone (CORT) replacement on hypothalamic neuropeptide levels were published in 2002 (8). Subsequently, AgRP was measured in plasma samples collected at the time of euthanasia from 12 ADX animals with (n = 6) and without (n = 6) CORT replacement, but these results were never published. We now report these plasma AgRP levels and correlate them with previously measured hypothalamic AgRP mRNA levels. Adult male Sprague-Dawley adrenalectomized rats (200 to 225 g) were purchased from Zivic Miller. They were provided 0.8% NaCl to drink and had free access to Purina Rodent Chow 5001 (Nestlé Purina, St. Louis, MO). CORT was replaced by subcutaneous implantation of 21-day release 50-mg CORT tablets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) (9). Rats were euthanized 10 days later; blood was collected, and the hypothalamus was dissected as reported previously (9).

Human studies

Peripheral EDTA plasma, serum, and 24-hour urine samples were collected from 31 patients with ACTH-dependent CD before transsphenoidal surgery. Blood samples were collected between 0800 and 1000 hours. In a subset of 13 patients with CD, blood samples were also prospectively collected at 1 week, 3 months, and 6 to 12 months after surgery. Glucocorticoid replacement was held the morning of blood draws in patients with CD who had postoperative adrenal insufficiency. Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected at the 6- to 12-month postoperative time point in all 13 prospectively evaluated patients.

Peripheral EDTA plasma and serum samples were collected from healthy volunteers the morning after an overnight fast, in the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle when applicable.

Assays

Rodents

Plasma AgRP was measured in rats by RIA after plasma extraction. The RIA used an antibody (RRID: AB 2686900) provided by Dr. Gregory Barsh and human AgRP83-132 standard and iodinated tracer. There is 20% cross-reactivity with full-length AgRP on a weight basis (26). EDTA plasma samples (0.5 mL) were mixed 1:1 with 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and applied to Sep-pak C18 cartridges (Waters Associates, Milford, MA). The cartridges were then washed with 1% TFA, and AgRP was eluted with 80% methanol in 1% TFA. The eluate was then evaporated and dissolved in assay buffer for RIA. Hypothalamic AgRP mRNA was isolated and quantitated by solution hybridization assay as previously reported (8). Results are presented as pg/µg total RNA.

Humans

AgRP was assayed by two-site ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) using a recombinant full-length human AgRP standard. There is 17% cross-reactivity with the C-terminal peptide, AgRP83-132 (27). Serum cortisol was assayed by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) on a Cobas immunoassay analyzer; 24-hour UFC was assayed by quantitative liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry at three well-known commercial laboratories (ARUP Laboratories, LabCorp, and Quest Diagnostics Inc.). ACTH was assayed by using a solid-phase, two-site sequential chemiluminescent immunometric assay using an Immulite 1000 immunoassay analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Inc., Tarrytown, NY). Plasma leptin was measured by ELISA (R&D Systems) with appropriate dilutions.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences in the parameters studied were evaluated between patients with CD and healthy controls by using paired t tests. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and the significance level was set at P < 0.05. Correlations were determined by simple linear regression analysis with Pearson correlation. Cross-sectional associations were assessed in multiple linear regression models, controlling for BMI and age. Longitudinal data were analyzed by using linear mixed effects model with random subject effects to account for within-subject correlation. Analyses were performed with Prism, version 6 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), or SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Effect of CORT replacement on plasma AgRP in ADX rats and correlation with changes in hypothalamic AgRP mRNA expression

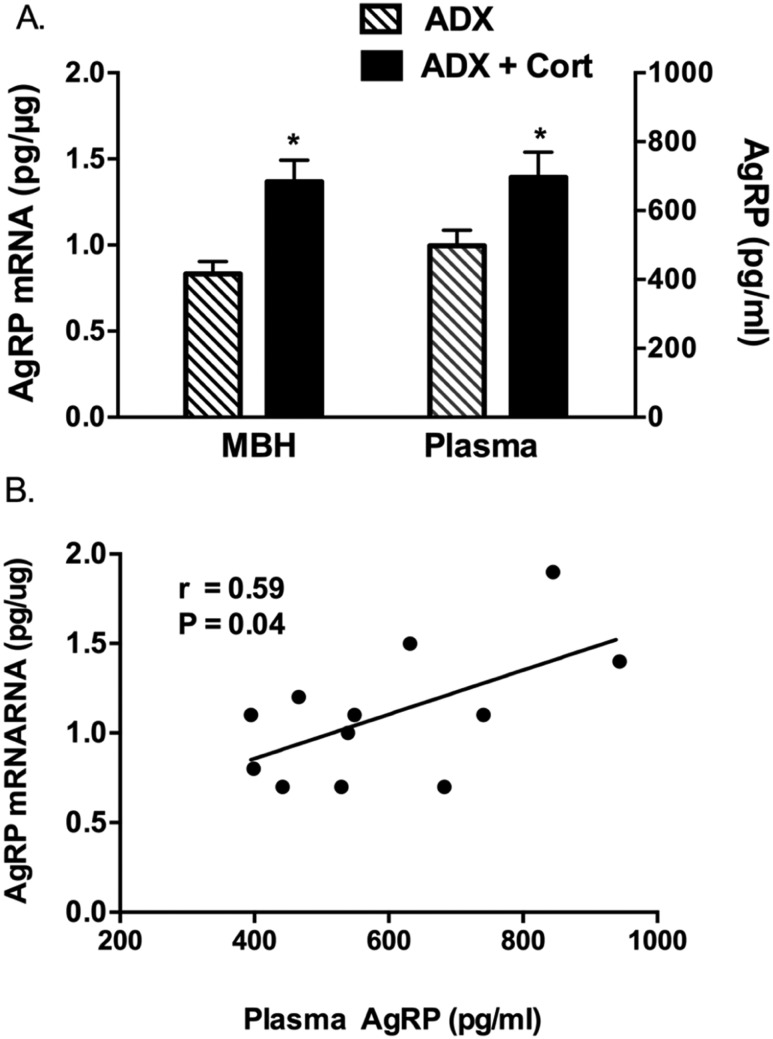

Mean CORT levels were 10.8 ± 1.4 μg/dL in the CORT-replaced ADX rats. Mean plasma AgRP levels were significantly higher in ADX rats receiving CORT replacement (696 ± 74 pg/mL) than in ADX rats without replacement (498 ± 45 pg/mL) (P = 0.04). Hypothalamic AgRP levels in the same animals were also significantly higher in the CORT-replaced rats (1.37 ± 0.12 pg/µg RNA) than in the ADX rats without replacement (0.83 ± 0.07 pg/µg) (P = 0.004), as previously reported. Thus, there was a parallel increase in hypothalamic AgRP expression and plasma AgRP after CORT replacement. There was a significant positive correlation between the concentrations of AgRP in the hypothalamus and in plasma (r = 0.59; P = 0.04) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Mean AgRP mRNA and plasma AgRP concentrations in ADX rodents with and without corticosterone replacement. (B) Correlation between hypothalamic AgRP mRNA and plasma AgRP concentrations. *P < 0.05. MBH, medial basal hypothalamus.

Retrospective evaluation of plasma AgRP concentrations in humans with CD

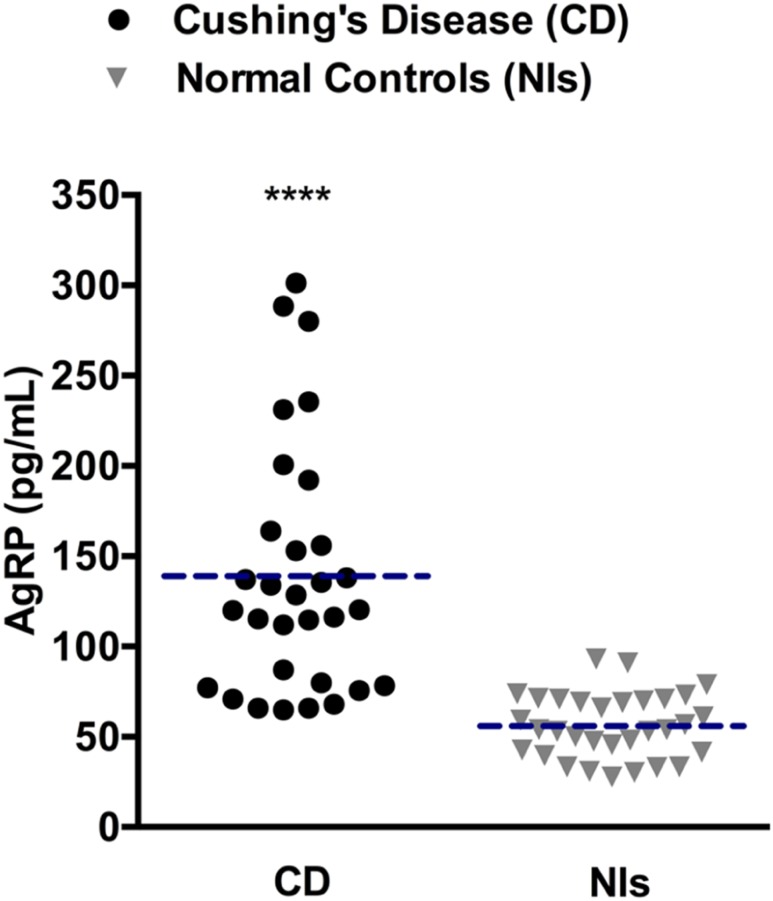

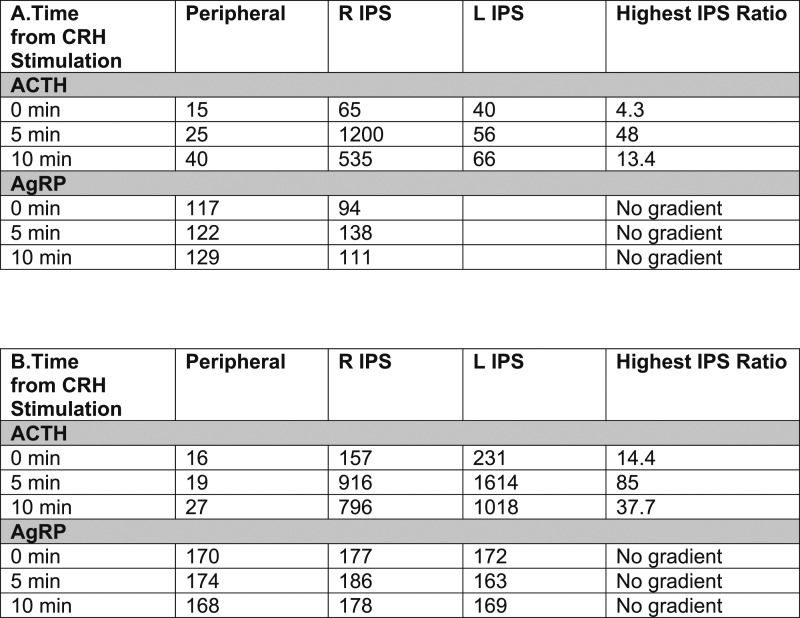

AgRP levels in the 31 patients with CD and 31 healthy controls matched for BMI, age, and sex (Table 1) are shown in Fig. 2. Among healthy controls, AgRP levels ranged from 28 to 93 pg/mL. Among patients with CD, AgRP levels ranged from 65 to 301 pg/mL. Despite some overlap between the two groups, plasma AgRP levels were higher in most patients with CD. Accordingly, mean plasma AgRP concentrations were significantly higher in patients with CD than in healthy controls (139 ± 12.3 vs 54.2 ± 3.1 pg/mL; P < 0.0001). Given this observation, we measured AgRP levels in stored inferior petrosal sinus samples from patients with CD in this cohort to evaluate for a potential pituitary AgRP source. As demonstrated by the representative data from inferior petrosal sinus sampling in two patients with CD from this cohort, a central-to- peripheral AgRP gradient was not identified (Fig. 3), suggesting there is not a tumoral AgRP source in CD.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of plasma AgRP levels in patients with CD and normal controls (Nls). The dashed horizontal lines represent mean plasma AgRP levels in each group. ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

ACTH (pg/mL) and AgRP (pg/mL) levels in inferior petrosal sinus samples from two representative patients with CD. Samples were obtained immediately before (0 min) and then 5 and 10 min after CRH stimulation. Peripheral refers to blood samples obtained from a peripheral vein in the forearm. Highest IPS ratio refers to the ratio of central ACTH or AgRP from the right inferior petrosal sinus and left inferior petrosal sinus to peripheral ACTH or AgRP, that is the highest at the time point being evaluated. IPS, inferior petrosal sinus; L IPS, venous blood sampled from the left inferior petrosal sinus; R IPS, venous blood sampled from the right inferior petrosal sinus.

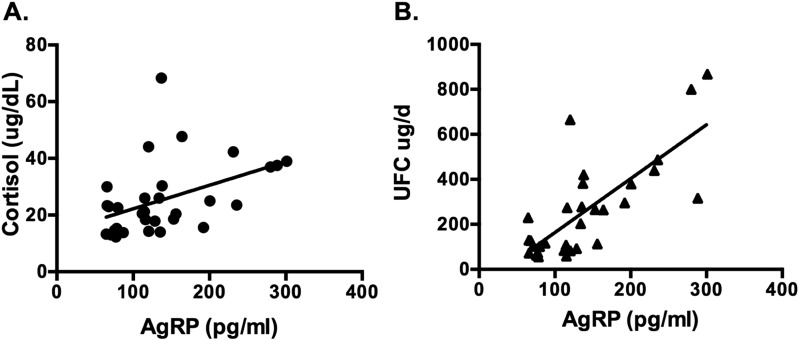

Mean plasma ACTH concentrations were 70 ± 7.0 pg/mL and serum morning cortisol and 24-hour urine free cortisol levels were 25.6 ± 2.3 μg/dL and 257 ± 38.9 μg/d among those with CD (Table 1). Plasma AgRP and ACTH levels were not correlated; however, a significant positive correlation between plasma AgRP and serum cortisol levels (r = 0.45; P = 0.01) was noted (Fig. 4A), which persisted after adjustment for age and BMI (P = 0.006). A highly significant positive correlation between plasma AgRP and 24-hour urine free cortisol levels (r = 0.76; P < 0.0001) was also observed (Fig. 4B), which similarly persisted after adjustment for age and BMI (P < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Correlations between plasma AgRP concentrations in 31 patients with CD who have active hypercortisolism. (A) Serum cortisol levels: r = 0.45; P = 0.01. (B) 24-h UFC levels: r = 0.76; P < 0.0001. Plasma AgRP correlated positively with both serum and UFC concentrations.

When we evaluated the relationship between plasma AgRP and BMI among patients with CD, we identified an inverse association (as previously reported in healthy persons) that approached significance (r = −0.35; P = 0.05).

Prospective evaluation of plasma AgRP in humans with CD undergoing curative transsphenoidal surgery

When we prospectively evaluated dynamic changes in plasma AgRP before and following curative transsphenoidal surgery in 13 patients with CD, adrenal insufficiency was observed 48 hours after surgery in 12 of the 13. All adrenally insufficient patients received postoperative glucocorticoid replacement in the form of oral prednisone (11 of 12) or hydrocortisone (1 of 12). Mean prednisone doses were 9.8 ± 0.3 mg and 5.0 ± 1.0 mg at the 1-week and 3-month postoperative time points, respectively. The single patient who received hydrocortisone was taking 20 mg every morning/10 mg every evening 1 week after surgery and continued receiving 15 mg every morning/10 mg every evening at the 3-month postoperative time point. At 6 to 12 months after surgery, 9 patients continued receiving physiologic glucocorticoid replacement and 11 of 13 patients had evidence of persistent postoperative cure.

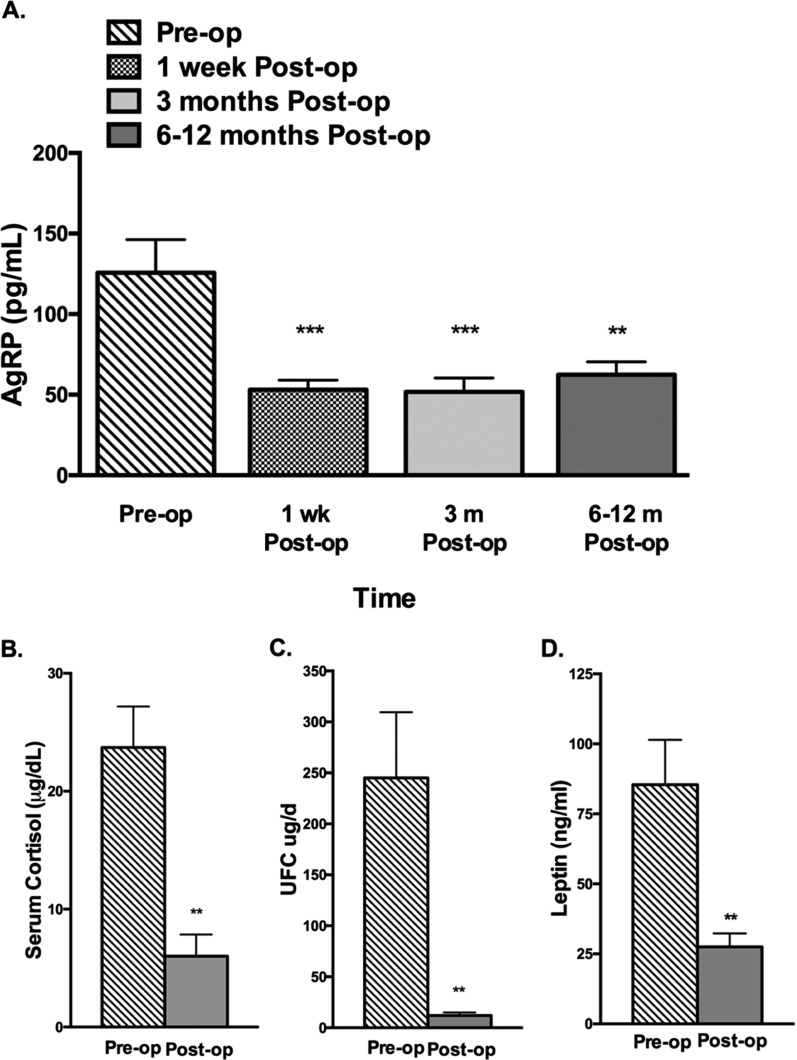

Among the 11 cured patients, by 1 week after surgery mean plasma AgRP levels significantly declined, from a baseline of 126 ± 21 to 53.1 ± 5.9 pg/mL (P < 0.05). Plasma AgRP levels remained low at the 3-month (52 ± 8.5 pg/mL) and 6- to 12-month (62.5 ± 8.0 pg/mL) postoperative time points (Fig. 5). Mean serum cortisol concentrations declined in parallel, decreasing from 24.1 ± 3.5 μg/dL preoperatively to 1.1 ± 0.2 μg/dL (P < 0.0001) 1 week after curative transsphenoidal surgery and remained low at 1.8 ± 0.6 μg/dL 3 months after surgery, reaching 6.0 ± 1.8 μg/dL at the 6- to 12-month postoperative time point. As expected, a concomitant decrease in mean 24-hour UFC levels was also observed. Twenty-four hour UFC levels decreased from a preoperative baseline of 257 ± 38.9 to 12.1 ± 3.0 μg/24 hours 6 to 12 months after surgery (P = 0.004). BMI decreased from 36.1 ± 1.9 kg/m2 preoperatively to 30.4 ± 1.2 kg/m2 (P = 0.003) 6 to 12 months postoperatively, in parallel with a significant decline in leptin levels from 85.4 ± 16 pg/mL to 27.5 ± 4.8 pg/mL (P = 0.003).

Figure 5.

Mean concentrations of (A) plasma AgRP, (B) serum cortisol, (C) 24-h UFC, and (D) leptin in 11 patients with CD evaluated before and after surgery. **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005.

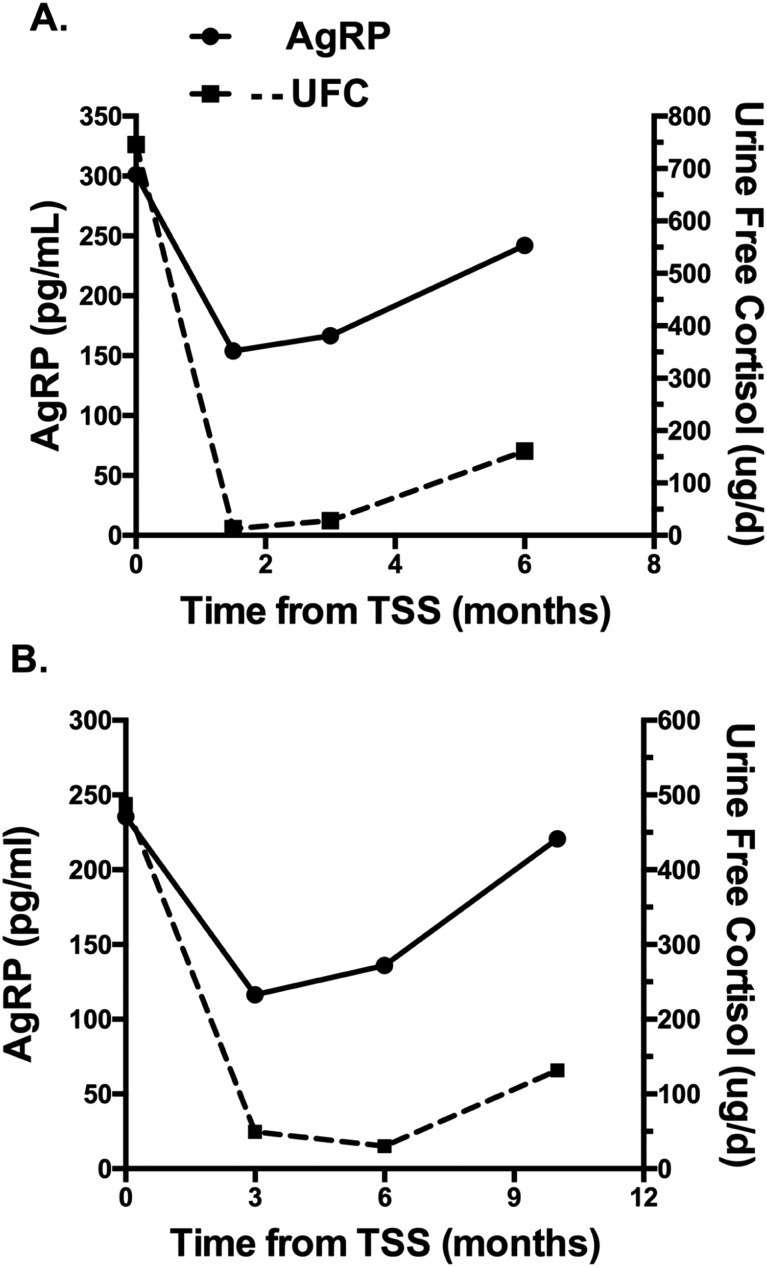

Prospective evaluation of plasma AgRP and UFC in recurrent CD

When changes in UFC levels and plasma AgRP were evaluated over time in 2 of 13 patients with CD who had evidence of postoperative recurrence of hypercortisolism, parallel increases in AgRP and UFC were observed (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

(A and B) Changes in plasma AgRP and UFC over time in two patients with CD before and after transsphenoidal surgery (TSS), with evidence of postoperative recurrence. Normal UFC concentrations are <50 μg/d.

Discussion

Glucocorticoids have repeatedly been shown to modulate AgRP expression in the arcuate nucleus of rodents (9–11), and deletion of glucocorticoid receptors from AgRP neurons has been shown to affect energy balance (12). In the current study, we expand on prior animal work from our group, to further demonstrate that plasma AgRP is a marker of hypothalamic AgRP. Our data show that hypothalamic AgRP expression and plasma AgRP change in parallel in response to corticosterone replacement in adrenalectomized rats. Furthermore, our data demonstrate a robust positive correlation between hypothalamic AgRP mRNA expression and circulating plasma AgRP concentrations in rats. These concomitant changes in AgRP expression and plasma AgRP levels in response to glucocorticoids parallel the rise in hypothalamic and circulating AgRP concentrations reported in response to fasting (19, 22, 28). Despite rodent data showing that glucocorticoids stimulate AgRP and evidence in both animals and humans, supporting plasma AgRP as a marker of hypothalamic AgRP (19, 20, 22), the relationship between glucocorticoids and plasma AgRP in humans had not been rigorously evaluated. We now confirm that CD, a state of glucocorticoid excess, is characterized by elevations in plasma AgRP that are strongly correlated with cortisol concentrations. Although we previously noted elevations in plasma AgRP in patients with CD compared with healthy controls, those controls were not matched for age and BMI (29). This is important because we have previously shown that BMI affects plasma AgRP levels and that there is a significant negative correlation between plasma AgRP and BMI in healthy humans (21).

The current data show that plasma AgRP concentrations are significantly higher in patients with CD than in controls matched for sex, age, and BMI; however, the inverse relationship between plasma AgRP and BMI observed in healthy humans tends to persist in CD. From an evolutionary perspective this relationship makes sense (30). Under steady-state conditions, one would expect lean individuals to have higher AgRP concentrations, given their small fat stores and low leptin levels. However, in the setting of chronic stress, or in this case chronic hypercortisolism, AgRP levels increase, stimulating food intake and fat storage in the face of perceived environmental uncertainty. These data also demonstrate a correlation between plasma AgRP and cortisol levels in patients with CD that is independent of BMI and age. Both serum cortisol and UFC levels are positively correlated with plasma AgRP, but the correlation between plasma AgRP and UFC levels is notably stronger, most likely because 24-hour UFC levels are a more integrated and sensitive measure of one’s overall cortisol status.

Our prospective data show that after curative transsphenoidal surgery, plasma AgRP levels fall as early as 1 week postoperatively, in parallel with a fall in cortisol levels, and remain suppressed in the setting of cortisol normalization. Although these data are consistent with a modulatory effect of glucocorticoids on plasma AgRP, we ruled out a potential tumoral AgRP source by measuring AgRP concentrations in inferior petrosal sinus sampling to evaluate for the presence of a central to peripheral gradient. AgRP concentrations in the pituitary venous effluent did not differ from peripheral concentrations, suggesting that the pituitary gland is not the source of circulating AgRP in CD. The postoperative fall in plasma AgRP following cure of hypercortisolism does parallel changes in plasma and hypothalamic AgRP observed in animals following adrenalectomy (9), further supporting the hypothesis that plasma AgRP is of hypothalamic origin. Although the source of circulating AgRP in humans has not been definitively established, the hypothalamic origin of circulating AgRP is also consistent with previous data showing that increases in plasma AgRP with fasting and diet-induced weight loss in healthy humans mirror expected changes in hypothalamic AgRP (20, 22). The hypothalamic origin of plasma AgRP is further supported by anatomic evidence showing heavy AgRP staining in the median eminence that could gain access to the peripheral circulation by capillary perivascular spaces that are contiguous with the arcuate nucleus (31, 32). One may have anticipated that if indeed plasma AgRP arises from the hypothalamus, AgRP concentrations in petrosal sinus blood would be higher than levels in peripheral veins. However, the pituitary venous runoff may not reflect drainage from this specific area of the hypothalamus. In addition, petrosal sampling occurs over a 10-minute period and the kinetics of AgRP release are unknown. The adrenal glands have also been considered as a potential source of circulating AgRP (33), but we now show in rats that plasma AgRP increases with corticosterone replacement even after adrenalectomy. We have also found that AgRP persists in human plasma following bilateral adrenalectomy in three cases (Page-Wilson G. Unpublished observations), suggesting that although it may be a contributing source the adrenals do not account for most AgRP in circulation.

Plasma AgRP concentrations in patients with CD fell after surgery in parallel with a decline in cortisol, despite a concomitant decrease in BMI and leptin levels. Thus, in humans, as in rodents, the modulatory effects of glucocorticoids on AgRP trump those of leptin. The changes in AgRP were pronounced after cure of CD and then levels remained relatively constant in the same participant over time. Although there is little information about the variability of plasma AgRP levels in healthy persons over time, our unpublished data show that levels are relatively constant. When we retrospectively evaluated plasma AgRP levels in six healthy weight-stable persons who had previously provided fasting morning blood samples on two separate occasions (an average of 22 months apart) while participating in studies conducted by our group, mean plasma AgRP concentrations were not significantly different at the two time points with plasma AgRP levels; they differed by a mean of 12.3% ± 4.3% (mean ± SEM) over time. Furthermore, data from a frequent blood sampling study conducted over 36 hours in eight healthy individuals demonstrate little variability in morning AgRP concentrations from day to day, although a modest diurnal AgRP rhythm was observed (34).

Given the low variability of plasma AgRP levels, our prospective data suggest that a postoperative rise in plasma AgRP may indicate an impending recurrence of CD. In 2 of 13 patients in this cohort with evidence of postoperative CD recurrence, a tight relationship between AgRP and UFC was observed under dynamic conditions. Although further study is needed, these data establish plasma AgRP as a potential biomarker in CD that could prove clinically useful both diagnostically and in long-term monitoring for tumor recurrence. Furthermore, because glucocorticoid receptors on hypothalamic AgRP neurons affect energy balance and metabolism in rodents (12, 16), the relationship between elevations in plasma AgRP in CD and the adverse metabolic effects of glucocorticoids should be investigated.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jean Tobin for her administrative assistance and Amanda Tsang for her excellent research coordination. We also thank Dr. John C. Ausiello for referring interested patients for participation and Dr. Bin Cheng for assistance with the statistical analyses. We express our sincere gratitude to the patients and volunteers who participated in these studies.

Financial Support: This work is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program grant #71591 (G.P.-W.) Medical Faculty Development Program grant #71591 (G.P.-W.), New York Obesity Nutrition Research Center grant P30 DK026687, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health grant UL1 TR000040. R01 DK093920 (S.L.W.) provided data for normal control subjects

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ADX

adrenalectomy

- AgRP

agouti-related protein

- BMI

body mass index

- CD

Cushing disease

- CORT

corticosterone

- MSH

melanocyte-stimulating hormone

- POMC

proopiomelanocortin

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- UFC

urine free cortisol

References

- 1. Zakrzewska KE, Cusin I, Stricker-Krongrad A, Boss O, Ricquier D, Jeanrenaud B, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. Induction of obesity and hyperleptinemia by central glucocorticoid infusion in the rat. Diabetes. 1999;48(2):365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mercer AJ, Hentges ST, Meshul CK, Low MJ. Unraveling the central proopiomelanocortin neural circuits. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee M, Wardlaw SL. The central melanocortin system and the regulation of energy balance. Front Biosci. 2007;12(8-12):3994–4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu Y, Elmquist JK, Fukuda M. Central nervous control of energy and glucose balance: focus on the central melanocortin system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1243(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature. 2006;443(7109):289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato I, Arima H, Ozaki N, Watanabe M, Goto M, Hayashi M, Banno R, Nagasaki H, Oiso Y. Insulin inhibits neuropeptide Y gene expression in the arcuate nucleus through GABAergic systems. J Neurosci. 2005;25(38):8657–8664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Korner J, Savontaus E, Chua SC Jr, Leibel RL, Wardlaw SL. Leptin regulation of Agrp and Npy mRNA in the rat hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13(11):959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korner J, Wardlaw SL, Liu SM, Conwell IM, Leibel RL, Chua SC Jr. Effects of leptin receptor mutation on Agrp gene expression in fed and fasted lean and obese (LA/N-faf) rats. Endocrinology. 2000;141(7):2465–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Savontaus E, Conwell IM, Wardlaw SL. Effects of adrenalectomy on AGRP, POMC, NPY and CART gene expression in the basal hypothalamus of fed and fasted rats. Brain Res. 2002;958(1):130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimizu H, Arima H, Ozawa Y, Watanabe M, Banno R, Sugimura Y, Ozaki N, Nagasaki H, Oiso Y. Glucocorticoids increase NPY gene expression in the arcuate nucleus by inhibiting mTOR signaling in rat hypothalamic organotypic cultures. Peptides. 2010;31(1):145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimizu H, Arima H, Watanabe M, Goto M, Banno R, Sato I, Ozaki N, Nagasaki H, Oiso Y. Glucocorticoids increase neuropeptide Y and agouti-related peptide gene expression via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase signaling in the arcuate nucleus of rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149(9):4544–4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shibata M, Banno R, Sugiyama M, Tominaga T, Onoue T, Tsunekawa T, Azuma Y, Hagiwara D, Lu W, Ito Y, Goto M, Suga H, Sugimura Y, Oiso Y, Arima H. AgRP neuron-specific deletion of glucocorticoid receptor leads to increased energy expenditure and decreased body weight in female mice on a high-fat diet. Endocrinology. 2016;157(4):1457–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee B, Kim SG, Kim J, Choi KY, Lee S, Lee SK, Lee JW. Brain-specific homeobox factor as a target selector for glucocorticoid receptor in energy balance. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(14):2650–2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagimoto S, Arima H, Adachi K, Ito Y, Suga H, Sugimura Y, Goto M, Banno R, Oiso Y. Expression of neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein mRNA stimulated by glucocorticoids is attenuated via NF-κB p65 under ER stress in mouse hypothalamic cultures. Neurosci Lett. 2013;553:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coll AP, Challis BG, López M, Piper S, Yeo GS, O’Rahilly S. Proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice are hypersensitive to the adverse metabolic effects of glucocorticoids. Diabetes. 2005;54(8):2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sefton C, Harno E, Davies A, Small H, Allen TJ, Wray JR, Lawrence CB, Coll AP, White A. Elevated hypothalamic glucocorticoid levels are associated with obesity and hyperphagia in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(11):4257–4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Makimura H, Mizuno TM, Roberts J, Silverstein J, Beasley J, Mobbs CV. Adrenalectomy reverses obese phenotype and restores hypothalamic melanocortin tone in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 2000;49(11):1917–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Makimura H, Mizuno TM, Isoda F, Beasley J, Silverstein JH, Mobbs CV. Role of glucocorticoids in mediating effects of fasting and diabetes on hypothalamic gene expression. BMC Physiol. 2003;3(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li JY, Finniss S, Yang YK, Zeng Q, Qu SY, Barsh G, Dickinson C, Gantz I. Agouti-related protein-like immunoreactivity: characterization of release from hypothalamic tissue and presence in serum. Endocrinology. 2000;141(6):1942–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shen CP, Wu KK, Shearman LP, Camacho R, Tota MR, Fong TM, Van der Ploeg LH. Plasma agouti-related protein level: a possible correlation with fasted and fed states in humans and rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14(8):607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Page-Wilson G, Meece K, White A, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Smiley R, Wardlaw SL. Proopiomelanocortin, agouti-related protein, and leptin in human cerebrospinal fluid: correlations with body weight and adiposity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309(5):E458–E465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Page-Wilson G, Nguyen KT, Atalayer D, Meece K, Bainbridge HA, Korner J, Gordon RJ, Panigrahi SK, White A, Smiley R, Wardlaw SL. Evaluation of CSF and plasma biomarkers of brain melanocortin activity in response to caloric restriction in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017;312(1):E19–E26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oldfield EH, Doppman JL, Nieman LK, Chrousos GP, Miller DL, Katz DA, Cutler GB Jr, Loriaux DL. Petrosal sinus sampling with and without corticotropin-releasing hormone for the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(13):897–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castinetti F, Morange I, Dufour H, Jaquet P, Conte-Devolx B, Girard N, Brue T. Desmopressin test during petrosal sinus sampling: a valuable tool to discriminate pituitary or ectopic ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157(3):271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Machado MC, de Sa SV, Domenice S, Fragoso MC, Puglia P Jr, Pereira MA, de Mendonça BB, Salgado LR. The role of desmopressin in bilateral and simultaneous inferior petrosal sinus sampling for differential diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66(1):136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breen TL, Conwell IM, Wardlaw SL. Effects of fasting, leptin, and insulin on AGRP and POMC peptide release in the hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2005;1032(1-2):141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Page-Wilson G, Reitman-Ivashkov E, Meece K, White A, Rosenbaum M, Smiley RM, Wardlaw SL. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of leptin, proopiomelanocortin, and agouti-related protein in human pregnancy: evidence for leptin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Katsuki A, Sumida Y, Gabazza EC, Murashima S, Tanaka T, Furuta M, Araki-Sasaki R, Hori Y, Nakatani K, Yano Y, Adachi Y. Plasma levels of agouti-related protein are increased in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(5):1921–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Page-Wilson G, Freda PU, Jacobs TP, Khandji AG, Bruce JN, Foo ST, Meece K, White A, Wardlaw SL. Clinical utility of plasma POMC and AgRP measurements in the differential diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):E1838–E1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(4):449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haskell-Luevano C, Chen P, Li C, Chang K, Smith MS, Cameron JL, Cone RD. Characterization of the neuroanatomical distribution of agouti-related protein immunoreactivity in the rhesus monkey and the rat. Endocrinology. 1999;140(3):1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shaver SW, Pang JJ, Wainman DS, Wall KM, Gross PM. Morphology and function of capillary networks in subregions of the rat tuber cinereum. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;267(3):437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ollmann MM, Wilson BD, Yang YK, Kerns JA, Chen Y, Gantz I, Barsh GS. Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science. 1997;278(5335):135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panigrahi SK, Hicks TJ, Lucey BP, Wardlaw SL. Characterization of the diurnal rhythm for cortisol and cortisone in human ceebrospinal fluid as related to the diurnal rhythm in blood and to changes in agouti-related protein (AgRP) Levels. Endocrine Society’s Annual Meeting 2018; Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]