Abstract

Background and objectives

The absence of accepted patient-centered outcomes in research can limit shared decision-making in peritoneal dialysis (PD), particularly because PD-related treatments can be associated with mortality, technique failure, and complications that can impair quality of life. We aimed to identify patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in PD, and to describe the reasons for their choices.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Patients on PD and their caregivers were purposively sampled from nine dialysis units across Australia, the United States, and Hong Kong. Using nominal group technique, participants identified and ranked outcomes, and discussed the reasons for their choices. An importance score (scale 0–1) was calculated for each outcome. Qualitative data were analyzed thematically.

Results

Across 14 groups, 126 participants (81 patients, 45 caregivers), aged 18–84 (mean 54, SD 15) years, identified 56 outcomes. The ten highest ranked outcomes were PD infection (importance score, 0.27), mortality (0.25), fatigue (0.25), flexibility with time (0.18), BP (0.17), PD failure (0.16), ability to travel (0.15), sleep (0.14), ability to work (0.14), and effect on family (0.12). Mortality was ranked first in Australia, second in Hong Kong, and 15th in the United States. The five themes were serious and cascading consequences on health, current and impending relevance, maintaining role and social functioning, requiring constant vigilance, and beyond control and responsibility.

Conclusions

For patients on PD and their caregivers, PD-related infection, mortality, and fatigue were of highest priority, and were focused on health, maintaining lifestyle, and self-management. Reporting these patient-centered outcomes may enhance the relevance of research to inform shared decision-making.

Keywords: Outcomes, Caregivers, blood pressure, quality of life, Self-Management, Decision Making, Patient Participation, peritoneal dialysis, Wakefulness, Life Style

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Health research aims to inform clinical practice and policy, but the absence of patient-centered outcomes can reduce the ability of research to inform shared decision-making among patients, their families, and their clinicians (1,2). In the context of trials, investigators typically select outcomes on the basis of their responsiveness to the intervention and feasibility, rather than those that are directly meaningful to patients, who are rarely involved in the selection of outcomes (3). Across medical specialties, the increasing recognition of the mismatch between the priorities of patients and researchers has prompted concerted efforts to ensure that patient-centered outcomes are identified and integrated into research (4–7).

In dialysis, patient-centered outcomes, such as fatigue and the ability to work, are infrequently reported across trials (8,9). Instead, biochemical markers, such as serum calcium, phosphate, and potassium, are often used because they are easier to measure and require a smaller sample size to show an effect (10,11). Peritoneal dialysis (PD)–related treatments may be associated with varying and uncertain risks of mortality and complications, including infection, pain, and technique failure, which in turn can have severe and direct consequences on the patient’s lifestyle, psychosocial wellbeing, overall quality of life, and caregiver burden (12). Patients have reported concerns about pain, body image, and the ability to self-manage (13–15); however, studies do not consistently report these outcomes (16,17).

In CKD, previous studies have elicited priorities for outcomes among patients on hemodialysis (8) and transplant recipients (18), but patient preferences for outcomes for research in PD remain to be systematically and explicitly identified. The aim of this study was to identify patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in PD, and to elicit the reasons underpinning these priorities. The selection of outcomes for research that are meaningful to patients on PD will ultimately result in a more patient-centered research agenda for these patients.

Materials and Methods

Participant Recruitment and Selection

We recruited patients on PD and their caregivers (i.e., a family member or friend involved in providing support and care) from three centers in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne. and Brisbane), one center in the United States (Los Angeles), and five centers in Hong Kong. These countries were chosen on the basis of geographical locality of the investigator team and to capture a diverse range of perspectives from patients and caregivers located in countries with different PD policies We applied purposive sampling to obtain a wide range of demographic (age, sex) and clinical characteristics (continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis [CAPD] versus automated PD, dialysis vintage, complications). Participants were eligible if they were 18 years or older, able to give informed consent, and English-speaking (or Spanish-speaking in the United States). We reimbursed participants US$50 in local currency for their travel expenses. Ethics approval was obtained from the Western Sydney Local Health District, Monash Health, Metro South Health, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute, Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee, University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, and the New Territories West Cluster Clinical and Research Ethics Committee.

Data Collection

We conducted 2-hour focus groups with an embedded nominal group technique from March to September 2017. The nominal group technique involved structured discussion to identify outcomes, followed by individual ranking of the outcomes, thereby allowing all participants to contribute equally (19). Each group discussion consisted of four phases: (1) discussion of experiences relating to PD; (2) generation of outcomes whereby participants, in turn, suggested outcomes that were augmented with outcomes from previous groups and outcomes reported in trials in the area of PD (16,17,20–23); (3) individual ranking of the importance of each outcome; and (4) discussion of the reasons for their rankings. One researcher (K.E.M. or A.T.) facilitated the groups, which were held in meeting rooms external to the hospital. The question guide is provided in Supplemental Table 1. Each session was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. An observer (K.E.M. or A.T.) recorded field notes on group dynamics and interactions during the session. Groups were convened until data saturation occurred i.e., when no new outcomes or insights were identified in subsequent groups.

Data Analysis

Nominal Group Ranking.

The importance score for each outcome is computed as the average of the reciprocal rankings. The reciprocal ranking is defined as 1 over the ranking assigned by each participant to each outcome. For example, if mortality is ranked first by one participant and third by another, the reciprocal rankings will be 1 and 1/3, respectively. If the outcome was not ranked by the participant, it was given a 0 as the reciprocal ranking. A higher reciprocal ranking indicates higher priority of the outcome. This score takes into account the importance given to the outcome by the ranking and the consistency of being nominated by the participants (24). A more detailed explanation is given in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Qualitative Analysis.

We entered transcripts into HyperRESEARCH software (version 3.7.3; ResearchWare Inc., Randolph, MA). Using thematic analysis, K.E.M reviewed the transcripts line by line and inductively identified concepts that reflected the reasons for participants’ identification and ranking of outcomes, and compared the concepts within and across groups to develop preliminary themes. The themes were discussed among the research team and revised to ensure that they reflected the full range and depth of the participants’ data.

Results

Participant Characteristics

In total, 126 patients/caregivers participated across the 14 groups (Table 1), with each group comprising 6–12 participants (Supplemental Table 2). The attendance rate was 89% and the reasons for nonattendance included work, other appointments, inability to arrange transportation, hospitalization, and illness. Thirteen groups were conducted in English language, and one group was conducted in Spanish language. Participants were aged 18–84 (mean 54, SD 15) years and 63 (50%) were women (Table 1). Eighty one (64%) participants were patients, of whom 35 (47%) were on CAPD, and 40 (53%) were on automated PD. Sixty patients (78%) had been on PD for <4 years. Of the 45 caregivers, 29 (64%) were spouses, six (13%) were parents, and six (13%) were siblings.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n=126)

| Characteristics | Australia, n=64 | United States, n=30 | Hong Kong, n=32 | All, n=126 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | 40 (62) | 18 (60) | 23 (72) | 81 (64) |

| Caregiver/family member | 24 (38) | 12 (40) | 9 (28) | 45 (36) |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 27 (42) | 20 (67) | 16 (50) | 63 (50) |

| Men | 37 (58) | 10 (33) | 16 (50) | 63 (50) |

| Age, yr | ||||

| 18–39 | 10 (16) | 11 (37) | 3 (9) | 24 (19) |

| 40–59 | 25 (39) | 14 (47) | 16 (50) | 55 (44) |

| 60–79 | 27 (42) | 4 (13) | 13 (41) | 44 (35) |

| 80–89 | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 11 (17) | 1 (3) | 29 (91) | 41 (33) |

| White | 32 (50) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 34 (27) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (2) | 18 (60) | 0 (0) | 19 (15) |

| Black | 0 (0) | 8 (26) | 0 (0) | 8 (6) |

| Othera | 20 (31) | 2 (7) | 2 (6) | 24 (19) |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| University degree | 16 (26) | 12 (43) | 15 (47) | 43 (35) |

| Diploma/certificate | 21 (34) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 23 (19) |

| Secondary school: year 12 | 10 (16) | 7 (25) | 11 (34) | 28 (23) |

| Secondary school: year 10 | 14 (23) | 5 (18) | 4 (13) | 23 (19) |

| Primary school | 1 (2) | 4 (14) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Retired/pensioner | 29 (45) | 3 (10) | 13 (41) | 45 (36) |

| Not employed | 13 (20) | 13 (43) | 4 (13) | 30 (24) |

| Full time | 11 (17) | 4 (13) | 8 (25) | 23 (18) |

| Part time/casual | 9 (14) | 5 (17) | 6 (19) | 20 (16) |

| Otherb | 2 (3) | 5 (17) | 1 (3) | 8 (6) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/partner | 46 (73) | 15 (54) | 24 (75) | 85 (69) |

| Single | 9 (14) | 8 (29) | 6 (19) | 23 (19) |

| Divorced/separated | 6 (10) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 9 (7) |

| Widowed | 2 (3) | 2 (7) | 2 (6) | 6 (5) |

| Type of peritoneal dialysisc | ||||

| CAPD | 16 (44) | 10 (63) | 14 (61) | 50 (53) |

| Automated PD | 20 (56) | 6 (38) | 9 (39) | 35 (47) |

| Time on peritoneal dialysisc, yr | ||||

| <1 | 13 (34) | 1 (6) | 7 (30) | 21 (27) |

| 1–3 | 22 (58) | 7 (44) | 10 (43) | 39 (51) |

| 4–6 | 2 (5) | 6 (38) | 5 (22) | 13 (17) |

| 7–10 | 1 (3) | 2 (13) | 1 (4) | 4 (5) |

| Prior KRTc | ||||

| In-center hemodialysis | 4 (10) | 7 (41) | 2 (9) | 13 (17) |

| Home hemodialysis | 4 (10) | 3 (18) | 2 (9) | 9 (12) |

| Kidney transplant (living donor) | 4 (10) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 5 (6) |

| Kidney transplant (deceased donor) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Multiple (hemodialysis and transplant) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 3 (4) |

| None | 25 (64) | 4 (24) | 16 (73) | 45 (58) |

Values are given as number (percentage). Numbers may not total (n=64, n=30, n=32, n=126) because of nonresponse. CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

Includes European, Indian, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander, and mixed ethnicities.

Includes volunteers, students, self-employed, and unspecified.

For patients only. Numbers may not total (n=40, n=18, n=23, n=81) because of nonresponse.

Nominal Group Ranking

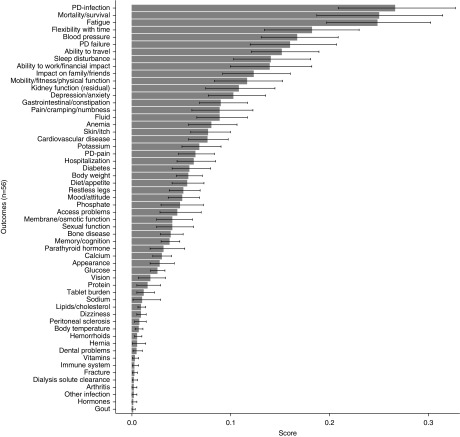

The participants identified a combined total of 56 outcomes. Across all participants, the ten highest ranked outcomes were PD infection (importance score, 0.27), mortality (0.25), fatigue (0.25), flexibility with time (0.18), BP (0.17), PD failure (0.16), ability to travel (0.15), sleep (0.14), ability to work (0.14), and effect on family (0.12) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall importance scores for all outcomes across groups (SEM bars).

Comparing across countries, the highest ranked outcomes were mortality (0.31), fatigue (0.25), and BP (0.23) in Australia; PD infection (0.36), fatigue (0.28), and flexibility with time (0.28) in the United States; and PD infection (0.29), mortality (0.28), and residual kidney function (0.24) in Hong Kong (Supplemental Figure 1). The top three outcomes for patients (n=81) were PD infection (0.27), fatigue (0.25), and mortality (0.23); and for caregivers (n=45) were mortality (0.29), PD infection (0.25), and fatigue (0.25) (Supplemental Figure 2). The outcome with the greatest difference in importance score between these two groups was ability to work (patients, 0.17 versus caregivers, 0.09). By sex, the top ranked outcomes for women (n=63) were PD infection (0.34), fatigue (0.23), and flexibility with time (0.21), compared with mortality (0.30), fatigue (0.27), and PD infection (0.20) for men (n=63) (Supplemental Figure 3). For age, the highest ranked outcomes for participants aged 55 years or older (n=63) were PD infection (0.30), fatigue (0.23), and ability to travel (0.18), whereas the top three for participants aged <55 years (n=62) were mortality (0.38), fatigue (0.25), and PD infection (0.24) (Supplemental Figure 4).

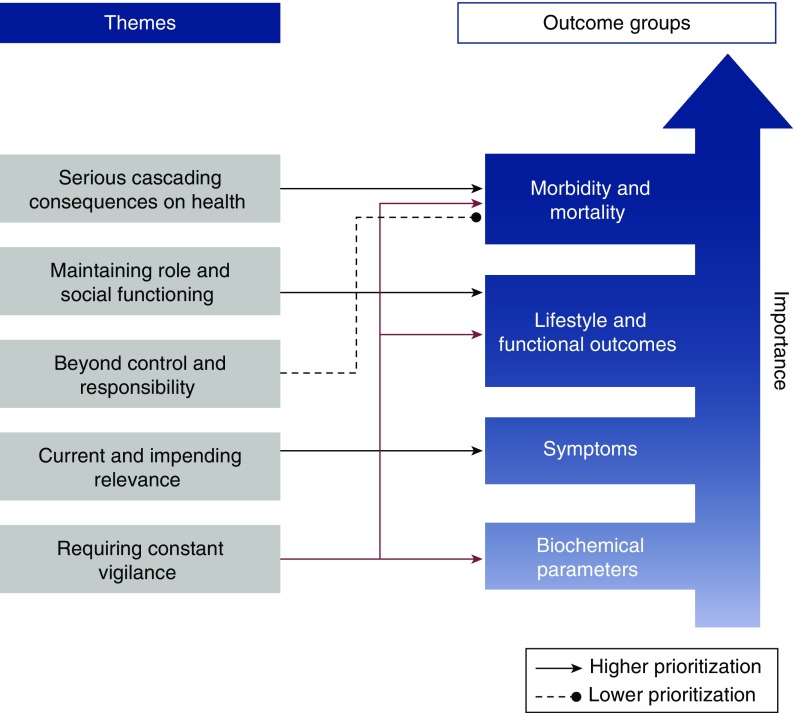

Qualitative Analysis

We identified five themes that explained participants’ ranking of outcomes. The description of the themes in the following section applied to both patients and caregivers unless otherwise specified. Supporting quotations for each theme are provided in Table 2. A thematic schema to show the conceptual links between the themes and ranking of outcomes is provided in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Selected illustrative quotations

| Theme | |

|---|---|

| Serious cascading consequences on health | |

| BP is very important because it always affect other organs. (M, patient, 70s, Hong Kong) | |

| If you’re constipated it’s going to give you an infection. It’s like a domino effect. One affects the other. Then you get fluid retention. Then you’re in the hospital. (F, patient, 50s, Los Angeles) | |

| Because they all go together. Because if the calcium ain’t right, you going to get in pain, and you’re going to end up in the hospital with a lot of pain. And they all three go together. So you’ve got to keep one in order to not have to deal with the other. (F, caregiver, 50s, Los Angeles) | |

| I’ve got number one as BP, because that’s what governs her. Her BP’s down, that’s it, you’re gone for the day, doesn’t matter what the rest of them are. If her BP’s okay, then you have an okay sort of day. (M, caregiver, 50s, Melbourne) | |

| I would say access problems. Because once that happens that’s no good. It goes downhill from there. (M, caregiver, 30s, Los Angeles) | |

| Survival number one. I had cardiovascular disease as number two. And kidney function as number three…because I guess without those being okay, everything else doesn’t matter. (M, caregiver, 30s, Hong Kong) | |

| A PD infection can lead to anything. If your PD infection is so bad you actually end up on, you know, not on the PD anymore. (F, patient, 30s, Brisbane) | |

| Current and impending relevance | |

| I’m retired, so it’s no longer a problem. (M, patient, 70s, Brisbane) | |

| I did it as to how I see him, the problems that, he’s going to go mad at this. Depression, one. Two, sleep. And three, sexual function. (F, caregiver, 50s, Brisbane) | |

| First one is energy. Second one is cardiovascular disease, and the third one is BP for me, because they’re all very relevant at the moment. Everything that we’ve discussed with either the renal team or the heart team centers around those three things. (M, patient, 40s, Brisbane) | |

| No surprise, because it [infection] always happens to so many renal patients. (M, patient, 50s, Hong Kong) | |

| The only thing I’m really concerned about with him is depression. I don’t know what to do about that. (F, caregiver, 60s, Brisbane) | |

| We try not to think about it, it’s a lot for you young ones. (F, patient, 50s, Melbourne) | |

| I would have put down draining about a year ago, when I first got on it, but I’ve just gotten used to using my laxatives and eating brown rice. It’s no longer a problem. (M, patient, 40s, Sydney) | |

| I’m 72, so really, mortality’s not a problem for me anymore, but I can understand for younger people with younger families. (M, patient, 70s, Brisbane) | |

| Maintaining role and social functioning | |

| Those three things [flexibility with time, ability to work, ability to travel] to my mind and heart, are what help you to remember what you are, in terms of they help to normalize your life for that person. Just remind you of what you are and also what you’re not, that you’re not just your illness, so it’s really important to be able to just keep things as normal as possible in the situation that you find yourself. (F, caregiver, 40s, Brisbane) | |

| If I have infection for renal patients, they take a lot of antibiotics for quite a long period of time, even stay in the hospital for a long time. We don’t have any freedom. Just stay there and wait for the doctors to discharge us. Very passive situation. (M, patient, 50s, Hong Kong) | |

| For one I put ability to work, two mobility, and three ability to travel…I guess you would feel normal if you could do those things.(F, caregiver, 20s, Los Angeles) | |

| For work, he’s a primary caregiver in my shoes, so to have him in hospital, and if it’s quite bad, it’s just an onset of income worry. (F, caregiver, 40s, Melbourne) | |

| Someone told me not to let dialysis control your life. If I have to go out, I make adjustments on the schedule. (F, patient, 60s, Sydney) | |

| Infection possibilities cause a lot of stress, and interrupt our family when she has to go to the hospital. (M, caregiver, 40s, Hong Kong) | |

| That’s why ability to work, travel, flexibility with time, it’s people’s main issue because we’ve all got mortgages we’ve got to pay, we’ve all got to live. (M, patient, 60s, Brisbane) | |

| If you have your anemia and BP under control you can have more energy and you can travel, you can go out, you can avoid much more complications having energy in your body…Energy is the base of the body, when you have energy you can pretty much endure everything. [translated] (M, caregiver 30s, Los Angeles) | |

| Requiring constant vigilance | |

| Every meal I’m always focused on what I can or cannot do, so much so that all my friends talk about, can you have this? Can you not have this? It’s in everybody’s conversation, every day, what I can have, what I cannot have…Your whole life is encompassing, you’re worried about it. You really don’t enjoy. (F, patient, 40s, Hong Kong) | |

| It’s just gone from cooking meals all the time to cooking, and you have to realize how much potassium’s in it. You go to grab something for tea, and you have to look on the back and read how much potassium is in that. (F, caregiver, 30s, Brisbane) | |

| It comes with the daily report. Every day you need to put the BP and fluid, because that means they are the most important things. Most important data. (M, 60s, Sydney) | |

| You never want to fail anything, so if you do get a PD infection, you’ve done something wrong and you upset yourself. (F, patient, 30s, Brisbane) | |

| There’s some sort of mental stress that you’re always anxious, about oh, am I doing this right, if I don’t do this, oh my gosh, I touched it, that means I got to go—you know what I mean? There’s all this cause and effect from everything. You stress about it, and I think there’s wear and tear on the psyche. (F, patient, 40s, Hong Kong) | |

| You have to pay attention to what you eat. [translated] (F, patient, 30s, Los Angeles) | |

| It’s one of the ways that you feel stressful, because you have to manage everything on time, on schedule. (M, patient, 60s, Hong Kong) | |

| It’s really great that he’s living, but there’s always that watchful—as a carer, I think, we’re always watching for the bad signs. (F, caregiver, 50s, Brisbane) | |

| If I have to go somewhere I have to make sure that I’m back home within a few hours because every 4–5 h I have to do my dialysis. But I have no choice, I have to do it. (F, patient, 50s, Hong Kong) | |

| Beyond control and responsibility | |

| If you sit there and dwell on all that, you might as well go and stick yourself in a straitjacket and go and put yourself in a room. Quite honestly, get on with life and just live it, and just let the doctors worry about your kidney function. Let them worry about all the other stuff there and just get on and live your life, really. (M, patient, 60s, Brisbane) | |

| My kidney function is already near zero, so it’s not important anymore. It’s already near zero, I’ve already lost it, it’s gone. (F, patient, 40s, Hong Kong) | |

| What can you do when that situation happens? Am I going to get depressed over it, because it [kidney function] is not coming back, so what can you do. Just deal with it like you’re dealing with all of the rest of the stuff. (F, patient, 50s, Los Angeles) | |

| Death is an inevitability. (M, patient, 60s, Sydney) | |

| It is important but it is something that can be cured, but how can you get energy, with a cream, or antibiotic?...What I’m saying is that infection is something that can be cured but energy, if you don’t have your kidney working properly, how are you going to get energy? I don’t think infection is so important. [translated] (M, patient, 30s, Los Angeles) | |

| We’re all going to die 1 d, some of us die quicker than others, but the quality of life has to be priority. (M, patient, 50s, Melbourne) | |

Information in italics indicates the sex, patient/caregiver status, age (years), and location of the patient. M, male; F, female; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 2.

Thematic schema depicting themes underpinning rankings of outcomes. Patients/caregivers gave higher priority to lifestyle and functional outcomes, and morbidity and mortality, compared with biochemical parameters and symptoms. The reasons for their prioritization are indicated in the themes. The theme of “requiring constant vigilance” contributed to higher prioritization of outcomes related to morbidity and mortality (e.g., PD infection), lifestyle and function (e.g., flexibility with time), as well as some biochemical parameters (e.g., potassium). “Current and impending relevance” contributed to the prioritization of outcomes relating to symptoms (e.g., sexual function, fatigue, depression), whereas the theme of “beyond control and responsibility” explained the lower prioritizations of morbidity and mortality-related outcomes, as patients felt some outcomes were inevitable (e.g., kidney function, mortality). “Maintaining role and social functioning” related to lifestyle and functional outcomes, such as the ability to work and travel. “Serious cascading consequences on health” justified the high prioritization of morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Serious Cascading Consequences on Health.

Higher rankings were given to outcomes if participants believed they led to serious and harmful effects on their health. Participants described this as a “domino effect,” where “one [outcome] affects the other” (“if you’re constipated it’s going to give you an infection…then you get fluid retention…then you’re in the hospital.”). BP was also considered a “very important” outcome because it “always affects other organs.”

Current and Impending Relevance.

Participants considered the importance of outcomes on the basis of the challenges they currently faced, and those commonly experienced among patients on PD. PD infection was ranked highly by most participants, and to them this was “no surprise, because it always happens to so many renal patients.” Some caregivers were concerned and felt helpless about the possible onset of depression in the patients they cared for, expressing that if it occurred they “don’t know what to do”; and thus ranked this outcome of high priority. The importance of outcomes such as mortality and the ability to work “depends on your age,” and for older participants were regarded as “no longer a problem.”

Maintaining Role and Social Functioning.

Participants gave higher priority to outcomes that enabled them to maintain their desired lifestyle or strengthened their resilience. Outcomes including the ability to work, travel, mobility, and flexibility with time, allowed participants to “feel normal,” and these reminded them of “what you are and also what you’re not, that you’re not just your illness.” Participants also ranked outcomes such as fatigue, infection, and hospitalization of higher importance because they caused disruption and inconvenience to daily living. This was particularly important for participants with young children or those who were the primary income earners: “he’s a primary caregiver in my shoes, so to have him in hospital, and if it’s quite bad, it’s just an onset of income worry.” Outcomes, such as energy (fatigue), were regarded by participants as necessary to cope with the challenges of the disease and treatment, and thus were ranked of high importance: “Energy is the base of the body, when you have energy you can pretty much endure everything.”

Requiring Constant Vigilance.

Outcomes that patients were required to avoid (e.g., PD infection) or control (e.g., potassium) were of high importance as patients constantly had to be “watchful” and “careful,” which they attributed to causing stress, anxiety, and “wear and tear on the psyche.” Flexibility with time was considered important, especially to patients on CAPD, as they felt it was “life-constricting that you have to be home particular times of the day” to perform a PD exchange. Some patients felt they had “no choice” but to adhere to their PD schedule, some discussed skipping exchanges out of convenience, and others had problems remembering to do their PD on time. Patients regarded fluid status, weight, and BP to be very important because they were instructed by their clinicians to monitor and record them daily: “Every day you need to put the BP and fluid, because that means they are the most important things.”

Beyond Control and Responsibility.

Some participants gave lower priority to outcomes, such as death or residual kidney function, because they considered that these were beyond their control or scope of responsibility: “Get on with life and just live it, and just let the doctors worry about your kidney function.” Outcomes were also given lower rankings if they were considered treatable: “It [infection] is important but it is something that can be cured, but how can you get energy, with a cream, or antibiotic?”

Discussion

For patients on PD and their caregivers, clinical outcomes (PD infection and mortality) and patient-reported outcomes (fatigue, flexibility with time, ability to travel, sleep, and ability to work) were the highest priorities. BP was the only surrogate outcome ranked in the top ten. These priorities for outcomes reflected concerns about the potential for serious consequences on health, immediate or likely risks of complications, disruption to their lifestyle, capacity for control, and self-management to minimize and manage the outcomes.

PD infection, including peritonitis, exit-site, and tunnel infections, was the highest ranked outcome overall, consistent with the frequency with which it is reported in trials (17,25). Patients felt they were constantly required to be extremely vigilant with their hygiene practices to minimize their risk of infection, which may jeopardize PD survival, cause pain, or require hospitalization. The patients’ focus on need to prevent an infection reflects findings from a recent study in which patients on PD described peritonitis as an ever-present concern, as they worried about the risk of PD failure or death, wanted to avoid hospitalization, and felt incapacitated to carry out their usual tasks (15).

Fatigue was ranked as the top patient-reported outcome, overall ranking third with an importance score almost equivalent to mortality. Patients emphasized that fatigue caused major disruptions to daily life, particularly for those who worked or had children dependent on them, and that it could be debilitating and undermine their ability to be resilient. In comparison, patients on hemodialysis and their caregivers ranked fatigue as the highest ranked outcome overall, describing it as incapacitating, psychologically draining, and detrimental to a patient’s overall wellbeing (8). Patients with other conditions, including rheumatic diseases and cancer, have also identified fatigue as an important outcome (26,27). Despite this high ranking of fatigue reported by patients on PD and hemodialysis, fatigue remains infrequently reported in trials in dialysis (9). Of note, studies have shown that health care providers underestimate both the prevalence and severity of fatigue in patients on dialysis (28).

Flexibility with time ranked fourth overall, and was defined as the ability to schedule dialysis according to one’s day. This was important for patients, particularly those on CAPD, as they felt constrained by having to schedule their lives around PD exchanges. Each day, they were required to monitor their time so they could return home in time to do PD, and some decided to skip an exchange of their own accord out of convenience or necessity. Flexibility with time allowed patient autonomy, which has the potential to improve patient satisfaction with treatment and adherence. Other studies have also shown that this outcome is a key contributing factor toward a patient’s choice of PD as a dialysis modality (29,30).

For some patients, the perceived importance of outcomes was, in part, influenced by what clinicians regularly measured in routine care, or what they were required to monitor on a daily basis. This was particularly relevant for BP, and to a lesser degree fluid status, which both ranked of relatively high importance because they were frequently monitored. Patients suggested that the responsibility of monitoring outcomes also enabled them to gain a sense of control and empowerment in their treatment, and were able to reassure themselves when they saw that their values were within the reference range.

There were differences in the importance of outcomes noted across participant subgroups, particularly in terms of patients versus caregivers, age, and country. Patients ranked the ability to work and mobility higher than caregivers, which reflected patients’ desire to maintain their lifestyle, autonomy, and sense of normality. This is consistent with previous studies, which found that reducing lifestyle disruptions and sustaining employment were important factors for patients when choosing between dialysis modalities (31). Caregivers, on the other hand, ranked effect on family and friends higher, which suggests a need for greater support for those who care for patients on PD (32). Studies have shown that the burden of responsibility among caregivers places them at risk of reduced quality of life and mental health (33–35). In comparison to younger participants (aged <55 years) for whom mortality was ranked first overall, participants in the older age group (>55 years) ranked mortality 11th, and gave higher priority to quality-of-life outcomes, including ability to travel and sleep. This suggests that decision-making requires consideration of the patients’ different goals and priorities across age groups. Participants in the United States ranked mortality lower (15th) compared with Australia (first) and Hong Kong (second). Mortality was discussed by participants in the United States as important; however, they gave higher rankings to outcomes that affected their daily functioning, such as pain and mobility, as well as outcomes that affected their potential to provide for or spend time with their families, including flexibility with time, the ability to work, ability to travel, and effect on family and friends (13). We speculate that some of the variability in outcome priorities across countries may be because of cultural differences or differences in health care systems.

This study was conducted in three countries and in two languages, and the mixed methods design enabled quantification of the relative importance of outcomes, as well as nuanced insights into the perspectives and reasons underpinning patient and caregiver choices. However, we acknowledge some potential limitations. Only patients who were able to travel and attend the focus group participated and thus may have precluded participation by patients who were frail or had very limited mobility. Because of ethical requirements, we were unable to collect the characteristics of individuals who declined to participate. We conducted groups with English-speaking participants (including in Hong Kong) and were only able to conduct one group in Spanish language because of resource constraints. As such, we could not compare by language groups. The broader transferability to the PD population in other countries is uncertain. Furthermore, most of the participants had been on PD for <4 years.

There is widespread recognition of the need to include patient-reported outcomes in research to enable shared decision-making on the basis of outcomes that reflect how patients feel or function, and patient-reported outcome measures are increasingly being implemented in research and clinical care. In our study, we have identified that fatigue, flexibility with time, ability to travel, ability to work, sleep, and effect on family are high-priority outcomes for patients, but specific measures for these outcomes have not been well validated in the PD population. Patient-reported outcome measures used in PD trials include the Short Form 36 (36,37) and EuroQol (22); however, these global instruments do not assess domains or items specific to the PD population. The Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL-SF or KDQOL-36) instrument incorporates the burden of CKD and has been recommended for use in the dialysis population (38). This measure has been used in some PD trials (39,40) and incorporates many aspects of the patient-reported outcomes identified in this study, including fatigue, ability to travel, and sleep, but it does not specifically measure flexibility with time, i.e., the degree of interference that dialysis has on a patient’s schedule.

This study will inform the development of a core outcome set for trials in PD, which incorporates the priorities of all stakeholders as part of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) initiative (41). To date, the SONG initiative has successfully developed core outcome sets in hemodialysis and kidney transplantation, using patient and caregiver priorities identified through nominal group technique and Delphi surveys (8,42,43). These outcomes will be used in the international SONG-PD Delphi Survey with patients, caregivers, and health professionals to gain consensus on the critically important outcomes to be included in all trials in PD. Consistent reporting of outcomes of direct relevance to patients in trials and clinical care can enable evidence-informed decision-making on the basis of patients’ preferences.

Patients on PD and their caregivers give high priority to clinical outcomes (such as PD infection and mortality) and many patient-reported outcomes (particularly fatigue and flexibility with time) that are absent in the majority of trials in PD. There is a need to focus the selection of outcomes toward those that are meaningful for patients on PD and their caregivers to support decisions about their own health, and to direct resources toward developing, evaluating, and implementing interventions that target these patient-centered outcomes.

Disclosures

K.E.M. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postgraduate Scholarship (APP1151343). A.T. is supported by a NHMRC Fellowship (APP1106716). D.W.J. is supported by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship. A.K.V. reports having received grant support from the NHMRC of Australia (Medical Postgraduate Scholarship) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Jacquot National Health and Medical Research Council Medical Award for Excellence). J.I.S. is supported by grant K23DK103972 from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Y.C. is supported by a NHMRC Early Career Fellowship. The funding organization had no role in the preparation, review, or approval or the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the patients and caregivers who gave their time to participate in the study.

Because R.M. is the Editor-in-Chief (EIC) of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, he was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. Another editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript. Ian de Boer, a Deputy Editor of CJASN, is at the same institution as some of the authors, including the EIC and therefore was also not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice, “Patient Priorities for Research Involving Peritoneal Dialysis,” on page 3.

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.05380518/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Appendix 1. Mathematical formula for nominal group technique ranking.

Supplemental Table 1. Focus group question guide.

Supplemental Table 2. Location and number of participants in each nominal group.

Supplemental Figure 1. Importance scores for outcomes by country: Australia, Hong Kong, and the United States.

Supplemental Figure 2. Importance scores for outcomes between patients and caregivers.

Supplemental Figure 3. Importance scores for outcomes between male and female participants.

Supplemental Figure 4. Importance scores for outcomes between participants over and under 55 years of age.

References

- 1.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S: Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 366: 780–781, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G: Patient preferences for shared decisions: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 86: 9–18, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P: Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 355: 2037–2040, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandhi GY, Murad MH, Fujiyoshi A, Mullan RJ, Flynn DN, Elamin MB, Swiglo BA, Isley WL, Guyatt GH, Montori VM: Patient-important outcomes in registered diabetes trials. JAMA 299: 2543–2549, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM, Howells DW, Ioannidis JPA, Oliver S: How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 383: 156–165, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, Schulz KF, Tibshirani R: Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet 383: 166–175, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) : Methodological standards and patient-centeredness in comparative effectiveness research: The PCORI perspective. JAMA 307: 1636–1640, 2012. 22511692 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urquhart-Secord R, Craig JC, Hemmelgarn B, Tam-Tham H, Manns B, Howell M, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG, Harris DC, Thompson S, Schick-Makaroff K, Wheeler DC, van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Johnson DW, Howard K, Evangelidis N, Tong A: Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: An international nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 444–454, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sautenet B, Tong A, Williams G, Hemmelgarn BR, Manns B, Wheeler DC, Tugwell P, van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Crowe S, Harris T, Evangelidis N, Hawley CM, Pollock C, Johnson DW, Polkinghorne KR, Howard K, Gallagher MP, Kerr PG, McDonald SP, Ju A, Craig JC: Scope and consistency of outcomes reported in randomized trials conducted in adults receiving hemodialysis: A systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 62–74, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yudkin JS, Lipska KJ, Montori VM: The idolatry of the surrogate. BMJ 343: d7995, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming TR, Powers JH: Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Stat Med 31: 2973–2984, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakewell AB, Higgins RM, Edmunds ME: Quality of life in peritoneal dialysis patients: Decline over time and association with clinical outcomes. Kidney Int 61: 239–248, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtin RB, Johnson HK, Schatell D: The peritoneal dialysis experience: Insights from long-term patients. Nephrol Nurs J 31: 615–624, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Lesmana B, Johnson DW, Wong G, Campbell D, Craig JC: The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 873–888, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell DJ, Craig JC, Mudge DW, Brown FG, Wong G, Tong A: Patients’ perspectives on the prevention and treatment of peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: A semi-structured interview study. Perit Dial Int 36: 631–639, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho Y, Johnson DW, Craig JC, Strippoli GFM, Badve SV, Wiggins KJ: Biocompatible dialysis fluids for peritoneal dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD007554, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ballinger AE, Palmer SC, Wiggins KJ, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Cross NB, Strippoli GFM: Treatment for peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD005284, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell M, Tong A, Wong G, Craig JC, Howard K: Important outcomes for kidney transplant recipients: A nominal group and qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 186–196, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen J, Dyas J, Jones M: Building consensus in health care: A guide to using the nominal group technique. Br J Community Nurs 9: 110–114, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DW, Brown FG, Clarke M, Boudville N, Elias TJ, Foo MW, Jones B, Kulkarni H, Langham R, Ranganathan D, Schollum J, Suranyi M, Tan SH, Voss D; balANZ Trial Investigators : Effects of biocompatible versus standard fluid on peritoneal dialysis outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1097–1107, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McQuillan RF, Chiu E, Nessim S, Lok CE, Roscoe JM, Tam P, Jassal SV: A randomized controlled trial comparing mupirocin and polysporin triple ointments in peritoneal dialysis patients: The MP3 Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 297–303, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li PK, Culleton BF, Ariza A, Do JY, Johnson DW, Sanabria M, Shockley TR, Story K, Vatazin A, Verrelli M, Yu AW, Bargman JM; IMPENDIA and EDEN Study Groups : Randomized, controlled trial of glucose-sparing peritoneal dialysis in diabetic patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1889–1900, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voss D, Hawkins S, Poole G, Marshall M: Radiological versus surgical implantation of first catheter for peritoneal dialysis: A randomized non-inferiority trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 4196–4204, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapelle O, Metlzer D, Zhang Y, Grinspan P: Expected reciprocal rank for graded relevance. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Hong Kong, China, November 2–6, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell D, Mudge DW, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Tong A, Strippoli GFM: Antimicrobial agents for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD004679, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A, Bresnihan B, Choy E, de Wit M, Hazes M, Richards P, Saag K, Suarez-Almazor M, Wells G, Hewlett S: Patient perspective: Fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 34: 1174–1177, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone P, Richardson A, Ream E, Smith AG, Kerr DJ, Kearney N: Cancer-related fatigue: Inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-centre patient survey. Cancer fatigue forum. Ann Oncol 11: 971–975, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, Levenson DJ, Cooksey SH, Fine MJ, Kimmel PL, Arnold RM: Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 960–967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee A, Gudex C, Povlsen JV, Bonnevie B, Nielsen CP: Patients’ views regarding choice of dialysis modality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3953–3959, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winterbottom A, Bekker HL, Conner M, Mooney A: Choosing dialysis modality: Decision making in a chronic illness context. Health Expect 17: 710–723, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker RC, Howard K, Morton RL, Palmer SC, Marshall MR, Tong A: Patient and caregiver values, beliefs and experiences when considering home dialysis as a treatment option: A semi-structured interview study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 133–141, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig JC: Support interventions for caregivers of people with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3960–3965, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimoyama S, Hirakawa O, Yahiro K, Mizumachi T, Schreiner A, Kakuma T: Health-related quality of life and caregiver burden among peritoneal dialysis patients and their family caregivers in Japan. Perit Dial Int 23[Suppl 2]: S200–S205, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantekin I, Kavurmacı M, Tan M: An analysis of caregiver burden of patients with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Hemodial Int 20: 94–97, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belasco A, Barbosa D, Bettencourt AR, Diccini S, Sesso R: Quality of life of family caregivers of elderly patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 955–963, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hare J, Clark-Carter D, Forshaw M: A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural group approach to improve patient adherence to peritoneal dialysis fluid restrictions: A pilot study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 555–564, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bro S, Bjorner JB, Tofte-Jensen P, Klem S, Almtoft B, Danielsen H, Meincke M, Friedberg M, Feldt-Rasmussen B: A prospective, randomized multicenter study comparing APD and CAPD treatment. Perit Dial Int 19: 526–533, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aiyegbusi OL, Kyte D, Cockwell P, Marshall T, Gheorghe A, Keeley T, Slade A, Calvert M: Measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) used in adult patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. PLoS One 12: e0179733, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paniagua R, Amato D, Vonesh E, Guo A, Mujais S; Mexican Nephrology Collaborative Study Group : Health-related quality of life predicts outcomes but is not affected by peritoneal clearance: The ADEMEX trial. Kidney Int 67: 1093–1104, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfson M, Piraino B, Hamburger RJ, Morton AR; Icodextrin Study Group : A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of icodextrin in peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 1055–1065, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manera KE, Tong A, Craig JC, Brown EA, Brunier G, Dong J, Dunning T, Mehrotra R, Naicker S, Pecoits-Filho R, Perl J, Wang AY, Wilkie M, Howell M, Sautenet B, Evangelidis N, Shen JI, Johnson DW; SONG-PD Investigators : Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Peritoneal Dialysis (SONG-PD): Study protocol for establishing a core outcome set in PD. Perit Dial Int 37: 639–647, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evangelidis N, Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Wheeler DC, Tugwell P, Crowe S, Harris T, Van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Sautenet B, O’Donoghue D, Tam-Tham H, Youssouf S, Mandayam S, Ju A, Hawley C, Pollock C, Harris DC, Johnson DW, Rifkin DE, Tentori F, Agar J, Polkinghorne KR, Gallagher M, Kerr PG, McDonald SP, Howard K, Howell M, Craig JC; Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology–Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) Initiative : Developing a set of core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: An international delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 464–475, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sautenet B, Tong A, Manera KE, Chapman JR, Warrens AN, Rosenbloom D, Wong G, Gill J, Budde K, Rostaing L, Marson L, Josephson MA, Reese PP, Pruett TL, Hanson CS, O’Donoghue D, Tam-Tham H, Halimi J-M, Shen JI, Kanellis J, Scandling JD, Howard K, Howell M, Cross N, Evangelidis N, Masson P, Oberbauer R, Fung S, Jesudason S, Knight S, Mandayam S, McDonald SP, Chadban S, Rajan T, Craig JC: Developing consensus-based priority outcome domains for trials in kidney transplantation: A multinational delphi survey with patients, caregivers, and health professionals. Transplantation 101: 1875–1886, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.