Abstract

During immune surveillance, T cells survey the surface of antigen presenting cells. In searching for peptide-loaded major histocompatibility complexes (pMHC), they must solve a classic tradeoff between speed and sensitivity. It has long been supposed that microvilli on T cells act as sensory organs to enable search, but their strategy has been unknown. We used lattice light sheet and Qdot-enabled synaptic contact mapping microscopy to show that anomalous diffusion and fractal organization of microvilli survey the majority of opposing surfaces within one minute. Individual dwell times were long enough to discriminate pMHC half-lives and T cell receptor (TCR) accumulation selectively stabilized microvilli. Stabilization was independent of tyrosine kinase signaling and the actin cytoskeleton, suggesting selection for avid TCR microclusters. This work defines the efficient cellular search process against which ligand detection takes place.

One Sentence Summary:

T cells use a dynamic fractal search pattern to palpate opposing surfaces; TCR occupied contacts are stabilized independently of signaling or actin.

T cells use surface-bound T cell receptors (TCRs) to identify ligands on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Detection results in rapid intracellular signaling, which is necessary for the acquisition of T cell effector functions and leads to adaptive immunity. The efficiency of search and detection has implications for the ability of T cells to discover rare epitopes and initiate a response (1), for example, during the early phases of a viral infection. The pathway to survey entire surfaces to detect rare ligands is likely to be exacerbated by the presence of a dense and wide glycocalyx, which is likely to inhibit whole scale surface-to-surface appositions (2, 3) and would seem to make small villi a preferred energetic solution toward detecting relatively short ligands.

TCR recognition happens at the same time as surface deformations provide initial contact (4–12). However, despite various fixed and lower-resolution approaches to understand this process, it has not been possible to study this complete surface in real-time in the full 3-dimensions in which it takes place. In particular, it is not clear how surface deformation is used to make detection efficient and whether the entire initial deformed surface is stable as soon as contact is made or whether cells might continue to “search” the surface in some form.

Fractal distribution of microvilli on the T cell surface and their effective scan of the opposing surface

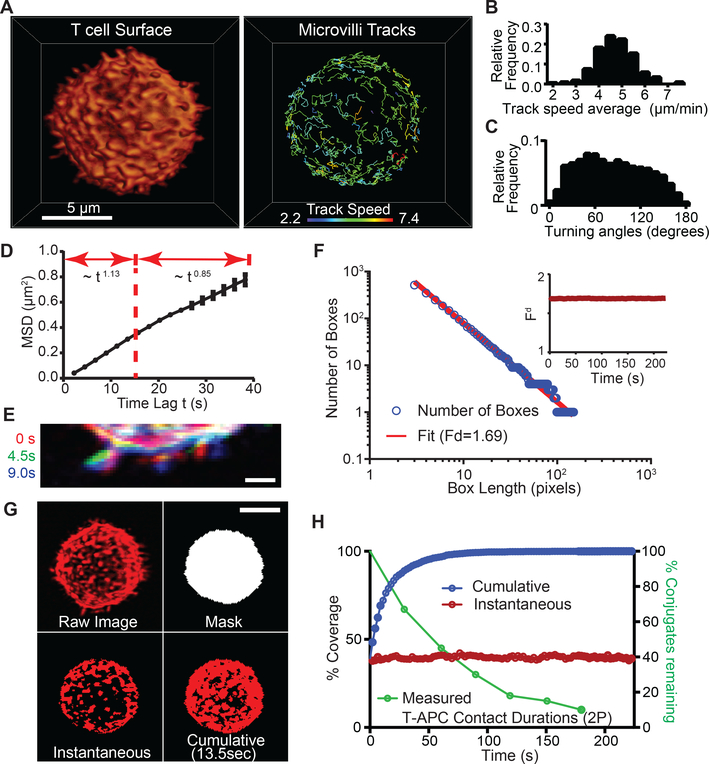

We imaged membrane deformations across the entire surface of mouse T cells in culture at 0.22–0.44 Hz at diffraction-limited resolution using lattice light sheet microscopy (LLS) (13). T cells were surface-labeled with either monodispersed non-stimulatory antibodies to the highly abundant surface molecule CD45 or using a membrane-bound form of the fluorophore tdTomato. Microvilli were found to be highly dynamic structures (Fig 1A and Movies 1 and S1). Most microvilli undulated and moved laterally, although we occasionally observed apparent reabsorption or projection from flatter membrane patches. We tracked microvillar movements and found that lateral displacements on the surface had a range of average speeds in individual cells (Fig 1B) with a mean across three cells of 5.2 ± 0.4 (SD) μm/min, which approximates the speed of T cell motility in vivo (14, 15). Microvillar movements covered a wide range of angles between timepoints (Fig 1C) with a close to uniform distribution of 82 ± 3 (SD) degrees (n=3), suggesting random turning. We characterized microvillar diffusive properties using mean squared displacement (MSD) by estimating the scaling exponent α in MSD~tα. We found that α = 1.13 for time scales within 15 seconds, which resembles superdiffusive motion (Fig 1D). Over longer time scales, α = 0.85 (resembling subdiffusion), suggesting that each microvillus might also be modestly confined and/or colliding with neighboring microvilli. Microvilli velocity correlations were positive, gradually decaying up to 10 – 15 seconds to become then negative (Fig S2A). The presence of negative velocity correlations beyond 15 seconds supports the idea that microvilli display subdiffusion on a longer time scale. Microvilli are all part of one surface and their free and persistent motion may thus only last until they interact with some neighboring microvilli. This will lower the search efficiency for an individual microvillus, but because free-ranging search occurs on time scales of less than 15 seconds, it will have less effect on the overall search efficiency.

Figure 1. Effective surface scanning by T cell protrusions.

(A) Surface projection rendering of a mouse T cell imaged by LLS (left). Isolated tracks for individual microvilli (right). See also Movies 1, S1. Tracking was assisted in some cases by image stabilization, to account for modest cell drift (Fig S1A). (B) Track speeds, (C) Turning angles and (D) MSD for microvilli (n>232 microvilli for all timepoints, across 3 cells). The curve follows the power law of MSD~tα, for t < 15 s, α = 1.13; and for t > 15 s, α = 0.85. Error bar corresponds to the standard deviation (SD). (E) Three-color overlay of a sub-section of an isolated T cell at three time points. Scale bar: 1 micron. (F) Fractal analysis: plot of the number of boxes needed to cover the active area of a T cell vs. length of the box (L). The slope of the fit line is used to determine the fractal dimension (Fd). Inset: Fd over time for a single T cell. (G) Representation of the masking and threshold method used to calculate the instantaneous and cumulative coverage of T cell surfaces and IS ROIs. Anti-CD45 was used to label cell surfaces in this example. Scale bar: 5 microns. See also Movie S2. (H) Left axis: Percentage of surface coverage (cumulative in blue, instantaneous in red) of an isolated T cell throughout time from LLS in vitro. Right axis: Percentage of T-APC contacts remaining vs. time, from 2-photon imaging data in vital lymph nodes.

The dynamics of microvilli were also visualized by sequential line-scans of a patch of membrane over three sequential timepoints (e.g. 9 seconds; Fig 1E), which revealed tilting in addition to lateral motion of microvilli. However, when assessed over > 1 minute periods (Fig S2B-C) similar analysis did not support “hot spots” for scanning. This suggests a potential underlying order that distributes these projections. We thus assessed microvillar distribution across length scales and time by performing fractal analysis. Fractal geometries in nature often provide consistent coverage across scales (16, 17), filling a volume or a surface in a compact and effective way, or assisting in finding adequate compromises between local exploitation and broad exploration (18). Plots of the logarithm of the number of regions that are necessary to contain all microvilli versus the logarithm of the region size gave a linear relationship across 1.5 orders of magnitude (Fig 1F and S4A-B), suggesting that microvilli distribution is indeed fractal. Notably, the observed fractal dimension Fd varied little with time (example Fig 1F, inset), suggesting that both a stationary stochastic and a complex dynamic process governs efficient microvillar-based scanning. Based on characterization of microvillar dynamics (Fig 1D), microvillar motion could be divided into two regimes: I. moderate superdiffusive motion over short time scales, and II. subdiffusive motion over longer time scales. These regimes may act similarly through time, which would account for a constant fractal dimension. The surface of the cell is on average quite crowded with microvillar protrusions given that a fractal dimension of 1.7 is relatively close to 2, namely, the topological dimension of the cell surface. However, the scaling (fractal) properties of microvillar protrusions cover a broad range of scales and ensure an efficient hierarchical embedding of the overall coverage, minimizing spatial overlaps.

To quantify how effectively these fractally distributed projections search opposing surfaces, we first considered a randomly selected cell-contact sized region just above the cell volume in the absence of any actual surface-contacts at that site (e.g. Mask, Fig 1G and Fig S1). We then quantified the distributions of microvilli projected from the T cell into that mask by applying a threshold to convert intensities into a binary map (e.g. Threshold, Fig 1G) using red to represent instantaneously “occupied” space and black to represent “unoccupied” areas. Further, to identify regions that have ever been scanned, we created a “Cumulative” image in which red now represents space that had a microvillus at that site at any time (example in Fig 1G shows total coverage achieved within 13.5 seconds). We then generated a time-series of these projections (Movie S2) and plotted the instantaneous and cumulative percent occupancy over time (Fig 1H). We found that cells had very consistent degrees to which they were instantaneously surveying such a region, here having an average of 39.8% and deviating less than 10% from this at any time (we observed variation in the mean coverage, cell-to-cell, from 35–45%, Fig 2B). Notably, the apparently random movements of microvilli resulted in a very rapid rise in cumulative coverage over time; 98% of the putative surface was visited by at least one microvillar contact within 1 minute (Fig 1H). For perspective, the half-life of T cell-APC contacts in vivo is roughly 1 minute (Fig 1H), suggesting that nearly complete scanning can be done at physiological dwell times.

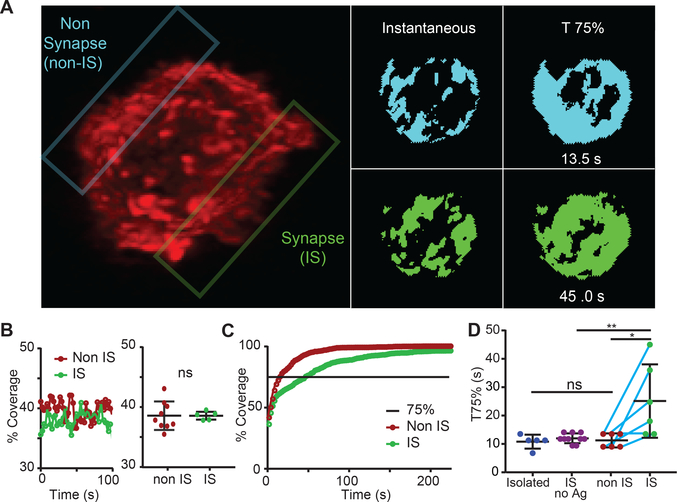

Figure 2. Altered microvillar cumulative coverage in response to ligand detection.

(A) Left: Image of a T cell in interaction with a peptide-loaded APC (unlabeled). The non-synaptic (non-IS) plane of interest is outlined in blue, the synapse (IS) is outlined in green. (See also Movie 2 for another example of an immunological synapse formed between a T cell and an APC with both cells labeled.) Right: Thresholded images of the non-IS (blue) and IS (green) contact face at a single timepoint and a cumulative image when coverage had reached 75%. (B) Left: Percent surface coverage throughout time for a non-IS and IS region of a single T cell. Right: The distribution of average surface coverage for non-IS regions and IS regions taken from multiple T cells. Error bar corresponds to SD, data are pooled from 4 separate experiments. (C) Percent cumulative coverage comparing the non-IS and IS region of a single T cell. Line indicates 75% surface coverage. (D) Comparison between the distributions of T75% for isolated T cells, IS regions with no antigen, non-IS regions, and IS regions of multiple individual T cells. Error bar corresponds to SD, data are pooled from 4 separate experiments. The significance test was unpaired t-test.

Altered microvilli dynamics upon antigen recognition

We next sought to determine whether membrane movements changed upon recognition of pMHC, presumably the goal for which the search is ideally tuned. We thus analyzed regions of the T cell surface that either were or were not in contact with the surfaces of opposing APCs bearing agonist pMHC complexes. An example of a T cell contacting a pMHC-bearing APC is shown in Movie 2. For the studied regions within the immunological synapse (“IS”) and outside (“non-IS”) another representative synapse is shown in Fig 2A. We found that instantaneous coverage did not vary appreciably over the time-course of synapse development for either location and that IS versus non-IS regions were similarly dense for protrusions (Fig 2B). This suggests that T cells did not intensify their search for antigens upon antigen recognition. However, a cumulative plot revealed that, in the IS, the rate of surface contact saturation actually slowed down (Fig 2C). To capture this, we adopted a metric (T75%) that reports the time at which 75% saturation of the contact is achieved, based on the 75% coverage point lying at the steep part of the contact saturation curve. In the example cell shown in Fig 2A, we found T75% was significantly faster (13.5 seconds) in non-IS compared to IS (25 seconds); and IS regions were slower to saturate as a class, compared to either isolated cells that were not making contacts with other cells or when comparing to non-IS regions in the same cells or synaptic regions without agonist pMHCs (Fig 2D).

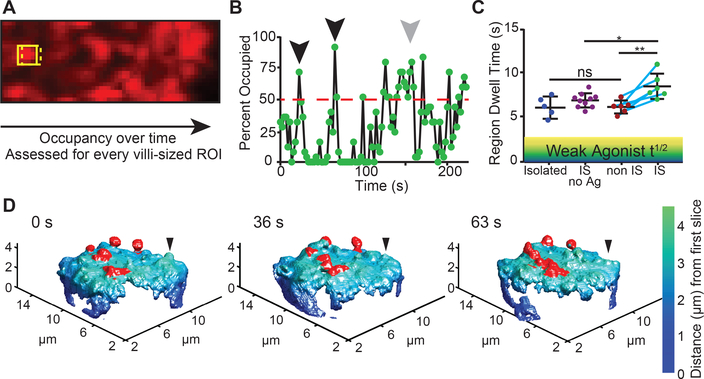

We hypothesized that the reduced saturation rate in the IS was a consequence of some protrusions being stabilized as a result of ligand detection, thus leaving fewer protrusions to scan new areas. To assess dwell time via LLS imaging from the perspective of the “target”, we developed an analytic method to analyze occupancy patterns at all the possible microvilli-sized (Fig S3) areas within a putative contact (Fig 3A). To extract how long such a region was continuously occupied by a T cell protrusion, we tracked the binary intensity of single-microvilli sized regions through time. A plot for a typical region is shown in Fig 3B, demonstrating times when microvilli passed through the region and exceeded a threshold of 50% coverage for just a single imaging timepoint (black arrow heads) or dwelled longer (grey arrow head). We plotted the average lifetime of all protrusions that were above the 50% cutoff for multiple cells and found similar lifetimes for isolated cells and for non-IS regions of cells that were engaging pMHC-bearing APCs (averaging 6.9 and 6.48 seconds respectively, Fig 3C). For IS regions of cells interacting with APCs in the absence of antigen, average dwell time was slightly longer (7.69 s). In contrast, average dwell times were the longest in the IS (8.9 seconds). We differentially color-coded protrusions in image sequences for an IS region, based on whether they visually persisted (Fig 3D and Movie S3). This highlighted the more stable microvilli that ceased to scan as extensively in the IS. Such stable contacts were typically but not exclusively localized in the center of the contact.

Figure 3. Altered microvillar regional dwell time in response to ligand detection.

(A) The scanning method for measuring regional dwell time over a contact surface. (B) Variation in occupancy, measured for a 25-pixel sized area, illustrating a cutoff at 50% occupancy. Short-lived protrusions are highlighted with the black arrows, while a longer-lived scanning event is shown in gray. (C) A comparison of the average regional dwell time, defined as in (B), for isolated T cells, IS with no antigen, non-IS regions, and IS regions in different T cells. Teal line connects individual cells. Shaded regions denote generalized half-life for weak-agonist pMHCs. Error bar corresponds to SD, data are pooled from 4 separate experiments. The significance test was unpaired t-test. (D) Membrane topology of the synaptic region of a T cell, labeled with anti CD45-Alexa488, interacting with a peptide-loaded APC at various timepoints. Stable protrusions are highlighted in red, an example transient protrusion is indicated with a black arrowhead.

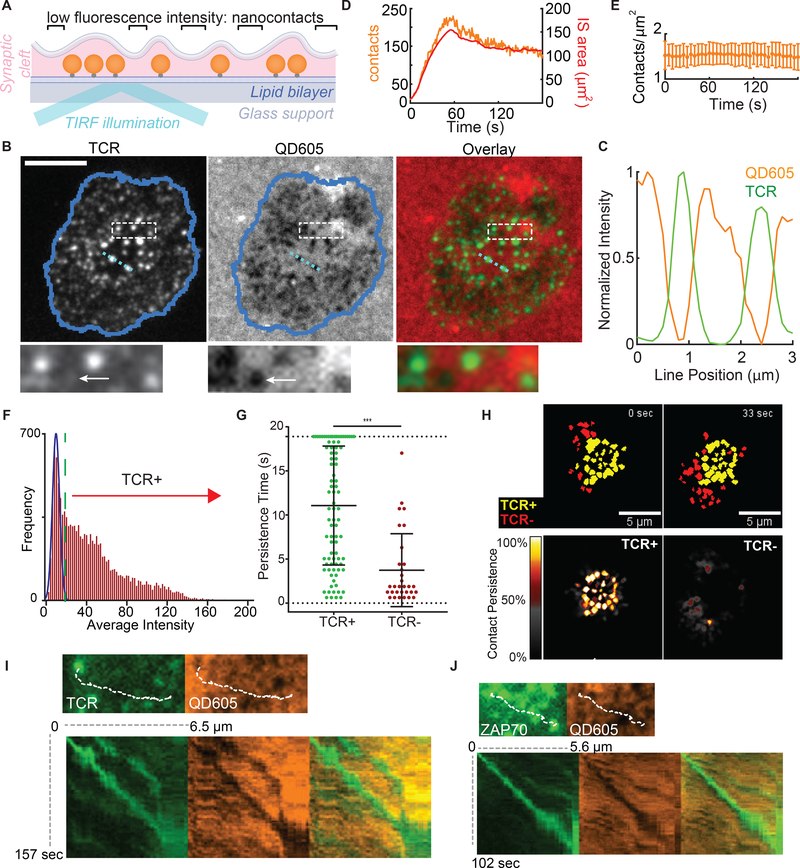

Synaptic contact mapping (SCM) of TCR-mediated protrusion-stabilization in the IS

These LLS data suggest stabilization of contacts might occur as a stochastic result of global signaling or as a specific consequence for those that had ligated their TCRs. We thus sought to visualize TCR microclusters together with these protrusion structures. While LLS imaging had proved facile for full cell volumes, we sought a companion tracking technique based on total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) imaging as a means to increase the scanning rate at the IS and focus upon nanometer level measurements of the contacts. We also sought to simultaneously visualize membrane apposition together with TCR density. Thus, we analyzed T cells that were settled upon supported lipid bilayers containing pMHC and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) (19, 20) to see if we could detect and thus study similar microvillar-like protrusions under these conditions. LLS imaging of fixed cells on bilayers (Fig S5A and Movie S4) also demonstrated that T cells generated microvillar-like projections. Scanning angle interference microscopy (Fig S5B) of T cells encountering lipid bilayers similarly confirmed that there were significant height variations of membrane for cells engaging lipid bilayers (Fig S5C). Notably bright TCR accumulations (microclusters) were closer to lipid bilayers as compared to the entire pool average, which is consistent with recent variable-angle TIRF studies showing TCR pre-enriched at microvillar tips (21). ICAM-1, a bigger molecule, was found farther away from the bilayer (Fig S5B-D).

To then study these contacts in real-time, we developed a method whereby quantum dots (Qdots), with a diameter larger than TCR-pMHC bond lengths, were seeded onto the lipid bilayers and used to specifically study close apposition on the scale of molecular interaction, akin to a “molecular ruler” (22) (Fig 4A and S6A). When T cells engaged bilayers containing ~16 nm Qdots, we observed “holes” in the otherwise uniform Qdot layer (Fig 4B) and found that intense TCR microclusters were inversely correlated with the Qdot intensity (Fig 4B-C). We confirmed that the contact “holes” and inverse correlation with TCR were specifically seen with larger 16 nm Qdots, but were essentially lost when smaller (~13 nm in diameter) Qdots or rhodamine formed the fluorescent layer (Fig S6B-C). These exclusion zones were likewise revealed when Qdots were added after synapses had formed (Fig S6E), showing that the Qdots did not induce the structures. We termed this method synaptic contact mapping (SCM) and found that SCM “holes” had mean diameter of 541 nm (Fig S6D) as compared to LLS imaging which estimated the mean microvilli thickness at 535nm (Fig S3). Also predicted from LLS imaging, these contacts could be observed to form as cells first spread onto bilayers (Fig 4D and Movie S5) and occurred at consistent densities over time (Fig 4E). We also applied SCM in a multichannel format to co-track multiple molecules alongside Qdots. TCRs co-localized with holes/contacts (Fig 4B), while LFA-1/ICAM-1, which are larger molecular interactions, were excluded (Fig S7).

Figure 4. TCR-occupied projections are stabilized.

(A) Schematic representation of bilayer-bound Qdots for SCM based imaging. Qdots larger than the ~ 15 nm TCR-pMHC length are excluded when membranes closely appose. See also Figure S6-S7. (B) Images of TCR, bilayer-bound QD605 streptavidin conjugates, and TCR/streptavidin overlays from cells fixed during synapse formation. Scale bars: 5 microns. Dashed box region is shown at the bottom. Arrow points to a contact with no apparent TCR microcluster. (C) Normalized intensities of Qdot605 and TCR line scan for the light blue line in (B). (D) Number of contacts and total IS area during IS formation. (E) Average contact density over time during IS formation. Error bars correspond to SD. Plot represents 28 cells pooled from 7 independent experiments. (F) Frequency histogram of the average intensity of all the contacts throughout the observation period. The blue Gaussian curve represents the intensity distribution expected from background sources for this region of interest. The green dashed line represents the cutoff from TCR+ to TCR−. (G) Dwell times in the TCR+ and TCR− populations within an 18.9 s observation window. Error bar corresponds to SD. The significance test was unpaired t-test. (H) Top: Overlay of TCR+ (yellow) with the TCR− contact populations (red) at 2 different timepoints. Bottom: Time projection of TCR+ (left) and TCR− (right). Colors represent the percentage of time of each pixel occupied by contacts over the length of the movie. (I) Top: Image of a nascent H57-labled TCR microcluster and corresponding contact image. Dashed line indicates the subsequent microcluster path. Bottom: kymograph generated from the microcluster path in each channel and overlay. (J) As (I) but for a ZAP70-GFP cluster.

“Holes” in the Qdot distribution were mapped using automated image analysis (Fig S8) and not all contact regions contained significant accumulations of TCRs (arrows in Fig 4B box-inset and Fig 4F). To quantify this and to determine whether TCR-occupied protrusions had longer dwell times in the IS, we defined a cutoff based on background TCR intensity levels across the entire imaging field (Fig 4F) and thereby defined “TCR+” versus “TCR−” contacts. We used 20-second windows of analysis to limit observations of rebinding and found that whereas TCR− SCM “holes” had a mean lifetime of 3.7 seconds, TCR+ SCM sites were stable for an average of 11.1 seconds (Fig 4G). Additionally, 25% of TCR+ SCM sites were stable for the entire observation period whereas none of the TCR− contacts persisted. While we have long recognized stabilized TCR microclusters as a feature of a signaling interface, this analysis reveals an additional ongoing search of the opposing surface that continues to take place, apart from microclusters (Fig 4H and Movie 3).

SCM also allowed us to study how 3D membrane dynamics underlie some of the movements of TCR microclusters that have previously been described (19, 23). We used kymographs of TCR tracks to show an exact correspondence between complex TCR movements and the movements of the underlying 3D protrusion (Fig 4I), and similarly for microclusters of the proximal kinase ZAP-70 (Fig 4J), showing that these movements are taking place in association with a stably surface-anchored projection. But, protrusions could also be seen to have more complex merging dynamics, which could result in conglomeration of TCR microclusters when both of the merging contacts were previously occupied (Movie S6). Merging took place even when only one (Movie S7) or neither contact contained an evident TCR microcluster, and microclusters themselves could both split and merge (Movie S8).

Notably, contacts were also observed in SCM images for B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (Movie S9) with different patterns, suggesting other immune cells survey the opposing surface with different strategies.

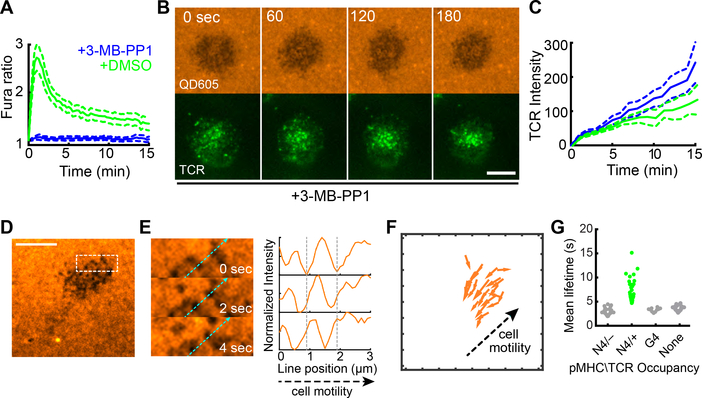

Actin cytoskeleton and signaling independence of TCR-mediated protrusion-stabilization

This data provided a framework for correlating membrane protrusion stability with TCR aggregation, and we sought to understand whether signaling and ensuing actin assemblies were required for modulating that stability. To assess this, we first used ZAP70 analog-sensitive (24) OT-I T cells, for which a specific kinase-inhibitor blocks signaling through the proximal kinase in TCR signaling. We found that although drug treatment fully blocked TCR-induced calcium signaling (Fig 5A, (24)), both microvillar probing and microcluster accumulation in stabilized contacts was at least as robust as in the absence of signaling (Fig 5B-C and Movie 4). Similarly, complete inhibition of all tyrosine phosphorylation with Src-family kinase inhibitor PP2 did not block microvillar scanning (Fig. S9A). In the absence of pMHC (ICAM-1 only on bilayers), “holes” were observed by SCM (Fig 5D) and moved retrograde to the direction of cell migration (Fig 5E-F). Furthermore, stabilization was specific to agonist-bearing complexes and null pMHC did not stabilize contacts (Fig 5G). While it has previously been observed that tyrosine kinase signaling is not necessary for microcluster aggregation (25), this result shows that cells continue to form microvilli, probe the surface and that TCR occupancy converts these protrusions to long-lived contacts.

Figure 5. Signaling independence of TCR-mediated protrusion stabilization.

(A) Fura-2 calcium ratios measured in ZAP70(AS)/OT-I T cells on activating bilayers after treatment with vehicle or 10 μM 3-MB-PP1. Plots represent the average Fura-2 ratio measured in over 100 cells pooled from 2 separate experiments. Error bar corresponds to the 95% CI. (B) QD605-streptavidin and TCR TIRF time lapse images of ZAP70(AS)/OT-I synapses after treatment with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1. Scale bars: 5 microns. (C) TCR intensity in contacts in ZAP70(AS)/OT-I T cell synapses. 3-MB-PP1: N = 12; DMSO vehicle: N = 9 cells. Data is pooled from 3 experiments. Error bars correspond to the standard error of the mean. (D) SCM images of bilayer-bound QD605-SA during encounter of OT-I T cell, without bilayer-bound pMHC but with ICAM-1. Scale bar: 5 μm. The boxed region measured 5 μm × 2 μm. (E) Left: Boxed region shown in (D). Light blue dashed line indicates direction of cell motility. Right, normalized intensity line scans for the light blue dashed line shown at left. The vertical gray dashed lines correspond to the starting point along the line for two contacts. The contacts moved against the direction of cell motility. (F) Displacement vectors for contacts shown in (D). For clarity, only tracks longer than 1 μm are shown. (G) Mean lifetimes for contacts based on the bilayer-bound pMHC complex and TCR occupancy. For the N4, the contacts are categorized based on whether it acquired TCR microclusters. For the G4 and null conditions, TCR+ microclusters were not observed. Data are pooled from at least 3 separate experiments for each condition.

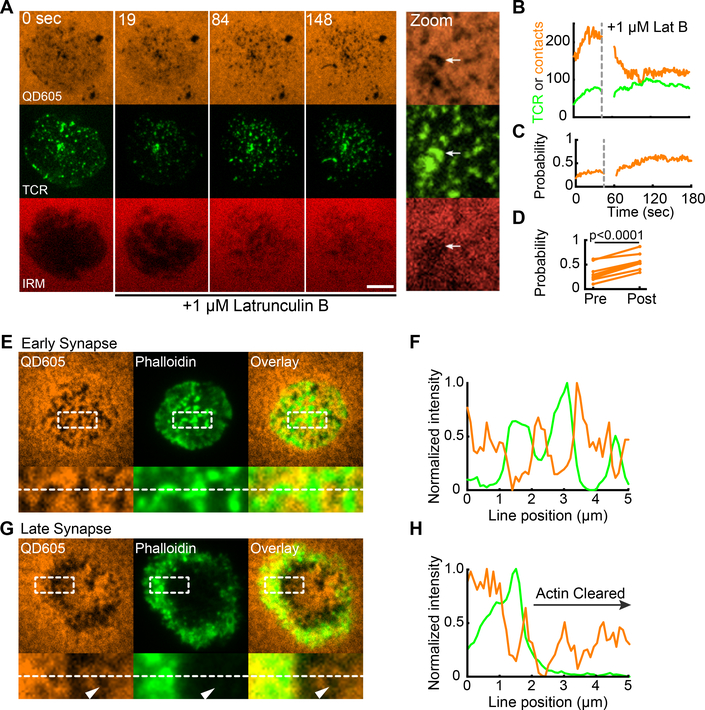

To explore this further, we tested the role for the actin cytoskeleton in stabilized contacts. Treatment of recently established synapses with Latrunculin B (LatB), which sequesters actin, results in actin disassembly, elimination of microvilli (Fig S9B), and the overall loosening of the cell cortex away from the bilayer, as visualized by a decreased interference reflection microscopy (IRM) signal (Fig 6A and Movie 5). However, the number of TCR microclusters remained steady after LatB addition even as the number of total contacts decreased to approximate the number of microclusters (Fig 6B). Plotting the probability of “occupancy” of a contact with a microcluster showed that actin depolymerization increased this probability; TCR+ contacts were selectively retained over time (Fig 6C, see also zoom in Fig 6A), both in a single cell and when viewed over many examples (Fig 6D). Consistent with this observation, we compared actin localization relative to these contacts in early (< 3 minute) synapses with late (> 6 minute) synapses in which actin depolymerization clears the majority of the central synapse (7, 19, 26). Whereas early contacts contain high densities of nucleated actin, the actin-void regions in later contacts, particularly of the central synapse, also supported contacts, which is consistent with their existence being actin-independent (Fig 6E-H). This confirms previous reports that showed actin to be dispensable for existing microclusters to persist (23) and that polymerized actin can be found at early sites of TCR signaling (25). However, it puts those findings in context of clear requirements for actin in most 3D contacts being compensated by the presence of TCR microclusters.

Figure 6. Cytoskeletal independence of TCR-mediated protrusion stabilization.

(A) Bilayer-bound QD605-streptavidin, TCR and IRM time lapse images of an OT-I IS during Latrunculin B (LatB) challenge. 1 μM LatB was added after acquisition of the t = 0 sec image. Scale bar: 5 microns. At right, a zoomed view of a region of the synapse 3 minutes after LatB addition. The white arrow points to a remaining patch of contacts with TCR microclusters and low IRM intensity. (B) Number of contacts (orange) and TCR microclusters (green) before and after LatB challenge for the IS shown in (A). (C) The fraction of contacts occupied by TCRs before and after LatB challenge for the IS shown in (A). (D) Average fraction of contacts occupied before and after LatB treatment. Each plot point represents the average fraction of contacts occupied in a cell measured over the 60 seconds before (pre-) and after (post-) LatB treatment. N = 7 cells pooled from 3 independent experiments. The significance test was paired t-test. (E,G) Top: QD605-streptavidin SCM and Phalloidin TIRF images of OT-I IS on activating bilayers. IS in (E) was fixed 3 minutes after addition of the cell to the bilayer. IS in (G) was fixed after 6 minutes and represents a mature synapse. Bottom: images of inset regions from images at top. Inset regions measure 5 μm × 2 μm. Images are representative of at least 25 cells imaged in 3 independent experiments. (F,H) Normalized line scan intensities for the dashed white line at bottom in (E) and (G), respectively.

Discussion

While clustering of TCRs has long been proposed to represent a fundamental signaling unit (27, 28), here we see that neither signaling nor cytoskeletal attachment were required for TCR microclusters to complete the search process and capture a membrane contact. It is intriguing that estimates for microvilli dwell times in the absence of ligands was ~3.5–6 seconds, depending on the method used to measure them in this study, because that range is long enough to discern short–lived antagonists (typical t1/2 of ~2 seconds) from longer-lived agonist pMHC-TCR complexes (29). Variations in that estimate from LLS to SCM methods may represent the sensitivity of the methods (e.g. with SCM-based tracking of a low intensity signal being susceptible to possible “dropping” of a contact) and/or the effects of simplified bilayers as compared to complex cell surfaces. While others have recently described immediately-stable “close contacts” (30) formed on glass surfaces that uniformly induce signaling associated with exclusion of large molecules such as the phosphatase CD45, contacts with native ligands are more dynamic and we did not observe profound CD45 exclusion in most contacts excepting occasional late, central synaptic membrane contacts. A series of future questions will need to address how molecules distribute at very small size scales on these tips but the ultimate result may resemble recently described micro-synapses (31). We also speculate that dynamic microvilli are the 3D structure on which previously described lipid rafts or “islands” are assembled, since islands have similar dimensions to microvilli, and that the movements and concatenations we describe on 3D surfaces are those on which such islands may merge or split (32). Addressing this will require further improvements in microscopy for multi-color LLS at higher frame rates.

This work shows that a topographic scan, or “palpation” of the opposing surface, underlies the act of TCR recognition and defines a key parameter in cell-cell recognition, namely the time pressure for ligands to solidify interactions with an opposing surface. Given that ligand density is tightly regulated in most biological systems, different cells are expected to take different approaches to this problem. We note that different immune cell types appear to survey more or less actively as compared to T cells and sometimes with waves or other patterns of membrane movements that are likely to lead to different efficiencies. Multiple additional levels of regulation of this process are now open to study.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mice were housed and bred at the University of California, San Francisco, according to Laboratory Animal Resource Center guidelines. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California. mTmG mice (33) were used in the absence of a corresponding Cre allele, resulting in membrane-tomato expression in all cells. ZAP70AS mice were as previously described (24).

Cell culture and retroviral transduction

OT-I T cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (complete RPMI). Single cell suspensions were prepared from the lymph nodes and spleens of OT-I TCR transgenic mice. Splenocytes were incubated in complete RPMI with 100 ng/mL of SIINFEKL peptide for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The splenocytes were washed three times and suspended in media. Lymphocytes and splenocytes were then mixed 1:1 at 2×106 total cells/mL, and 1 mL of the cell mix was transferred into each well of a 24-well plate. After 48 hours, 1 mL of media with IL-2 was added to each well (final concentration of IL-2: 100 U/mL). After 72 hours, cells were removed from the plate, transferred into fresh media with IL-2 and held in culture for an additional 24–48 hours before use.

For retroviral transduction, Phoenix cells were transfected with pCL-Eco and pIB2-Zap70-EGFP or pIB2-CD3ζ-GFP using Calcium Phosphate transfection. Supernatants were harvested and supplemented with IL-2. The supernatants were added to wells with T cells, and the plates centrifuged for 1 hour at room temperature. T cells were treated with supernatants from the Phoenix cells 48 and 72 hours after stimulation and then transferred to fresh complete RPMI. Phoenix cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (complete DMEM).

CH27 cells were maintained in complete DMEM and sub-cultured 1:10 every other day. J774.1 and RAW264.7 macrophages were maintained in complete DMEM and sub-cultured by scraping from plates with a cell scraper. Bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were prepared as described previously (34).

Cell preparation for imaging, fixation and staining

To prepare OT-I T cells for imaging, live cells were harvested using Ficoll-paque, washed with complete RPMI, and then held at 37 °C. To label TCRs for live cell imaging, 2×106 cells were stained with 1 μg of H57–597 non-blocking monoclonal antibody conjugated to either Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568 on ice for 30 minutes, then rinsed once with complete RPMI. Live cells were imaged in RPMI supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (imaging media). For time lapse image sequences, 2×105 cells were added to the bilayer well. Once cells began interacting with the bilayer, imaging was initiated.

For SAIM imaging, 5×105 cells were added to each well, allowed to bind for 3 minutes, and then fixed with 20 mM HEPES, 0.2 M Sucrose, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and 0.01% Glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes. The fixed cells were washed with 8 mL of PBS and then washed six times for five minutes with 1 mg/mL NaBH3. Chambers were then washed with PBS, and blocked with 2% Donkey or Goat serum. Cells were stained for two hours with 2 μg/mL anti-LFA-1 (M17.4) and then washed with PBS. Cells were then stained for 1 hour with 2μg/mL Donkey or Goat anti-Rat conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and 2 μg/mL H57–597 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568. Cells were then rinsed with PBS for imaging.

To prepare for LLS live cell imaging, BMDCs were washed with IMDM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (complete IMDM), and then incubated in complete IMDM with 100 ng/mL of SIINFEKL peptide for 30 minutes at 37 °C and rinsed 3 times in complete IMDM. For experiments with labeled BMDCs, 4×106 cells were incubated in 500 μl of serum-free IMDM with 4 μl/ml DiD, which are lipophilic tracers for labeling the cell membrane, for 15 min at room temperature and rinsed 3 times in complete IMDM before use. OT-I T cells were harvested using Ficoll-paque, washed with complete RPMI and then held at 37 °C. 2×106 OT-I T cells were stained with 2.5 μg of CD45 non-blocking monoclonal antibody conjugated to either Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 647 on ice for 30 minutes, then rinsed once with complete RPMI. For LLS imaging of non-treated T cells, cells were imaged in complete RPMI (no phenol red) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES. For LLS imaging of PP2-treated OT-I T cells, cells were incubated with either 10 or 100 μM PP2 for 1 hour at 37 °C. Cells remained in 10 or 100 μM PP2 throughout imaging.

For LLS fixed cell imaging on activating lipid bilayers, 2×106 OT-I T cells were stained with 2.5 μg of CD45 non-blocking monoclonal antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 on ice for 30 minutes and then rinsed once with complete RPMI. 5×105 cells were added to a 5 mm in diameter round coverslip sitting in an imaging well of 8-well Nunc Lab-Tek II chamered coverglass, allowed to bind for 6 minutes, and then fixed with 20 mM HEPES, 0.2 M Sucrose, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 0.01% Glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes. The fixed cells were washed with 8 mL of PBS for imaging.

Supported lipid bilayers

Preparation and use of supported lipid bilayers was performed as previously described (19). Briefly, phospholipid mixtures consisting of 96.5% POPC, 2% DGS-NTA (Ni), 1% Biotinyl-Cap-PE and 0.5% PEG5,000-PE in Chloroform were mixed in a round bottom flask and dried, first under a stream of dry nitrogen, then overnight under vacuum. All phospholipids were products of Avanti Polar Lipids. Crude liposomes were prepared by rehydrating the phospholipid cake at a concentration of 4 mM total phospholipids in PBS for one hour. Small, unilamellar liposomes were then prepared by extrusion through 100 nm Track Etch filter papers (Whatman) using an Avestin LiposoFast Extruder (Avestin).

8-well Nunc Lab-Tek II chambered coverglass were cleaned with 1 M HCl/70% Ethanol for 30 mins, followed by a rinse with water, then cleaned with 10 M NaOH for 15 mins. After cleaning, the chambers were washed repeatedly with 18 MΩ water and then dried. Lipid bilayers were set up on the chambered coverglass by adding 0.25 mL of a 0.4 mM liposome solution to the wells. After 30 minutes, wells were rinsed with 8 mL of PBS by repeated addition of 0.5 mL of PBS, then aspiration of 0.5 mL of the overlay. Non-specific binding sites were then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes. After blocking, 25 ng of unlabeled streptavidin was added to each well and allowed to bind to bilayers for 30 minutes. After rinsing, protein mixes containing 63 ng ICAM-1 and 6 ng pMHC in 2% BSA were injected into each well. ICAM-1 preparation was described previously (19) while pMHC was provided by the NIH Tetramer Facility. After binding for 30 minutes, wells were rinsed again and 25 ng of QDot-streptavidin, TRITC-streptavidin, or unconjugated streptavidin was added to each well. Bilayers were finally rinsed with imaging media before being heated to 37 °C for experiments.

For LLS fixed cell imaging on activating lipid bilayers, 5 mm in diameter round coverslips were cleaned with 1 M HCl/70% Ethanol for 30 mins, followed by a rinse with water, then cleaned with 10 M NaOH for 15 mins. After cleaning, the coverslips were washed repeatedly with 18 MΩ water, and then dried. The coverslips were dropped into cleaned 8-well Nunc Lab-Tek II chambered coverglass, and lipid bilayers were set up on the 8-well chambered coverglass as described above except that Qdots were not added to the lipid bilayer.

Analysis of Actin

For Latrunculin B challenge imaging by SCM, 2×105 cells were added to wells, and imaging was initiated for each cell as it began interacting with the bilayer. The cell was allowed to commence IS formation for about 45 seconds before injection of Latrunculin B to a final concentration of 1 μM. Injectant was a 0.5 mM solution of Latrunculin B in imaging media. Injectant was prepared from a 10 mM DMSO stock held at −20 °C until use. For LLS imaging of Latrunculin B-treated OT-I T cells, LatB was added to the imaging well to a final concentration of 1 μM.

To stain for F-actin, cells were added to bilayers and allowed to bind for 3–6 minutes, then fixed by addition of PFA to a final concentration of 4%. Cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, then permeabilized for 2 min with 1% Triton X-100. Cells were again washed, and nonspecific binding blocked by incubating for 30 minutes with 1% BSA. Cells were then stained for F-actin with 1 Unit of Alexa Fluor 488-Phalloidin (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were finally washed in PBS before imaging.

Lattice Light Sheet Microscopy

Lattice light-sheet (LLS) imaging was performed in a manner previously described (13). Briefly, 5 mm in diameter round coverslips were cleaned by a plasma cleaner, and coated with 2 μg/ml fibronectin in PBS at 37°C for 1 hour before use. BMDCs were dropped onto the coverslip and incubated at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 for 20–30 min. Right before imaging, OTI T cells were dropped onto the coverslip which had BMDCs. The sample was then loaded into the previously conditioned sample bath and secured. Imaging was performed with a 488 nm, 560 nm, or 642 nm laser (MPBC, Canada) dependent upon sample labeling in single or two-color mode. Exposure time was 10 ms per frame leading to a temporal resolution of 2.25 s and 4.5 s in single and two-color mode respectively.

Synaptic Contact Mapping (SCM) and Interference Reflection Microscopy (IRM)

The TIRF microscope is based on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M with a manual Laser TIRF I slider (19). To image nanocontacts and TCRs, image sequences consisting of TCRs (TIRF), QD-streptavidin (widefield), and interference reflection microscopy (IRM, widefield) images were collected. For TIRF images, a 488 nm Obis laser (Coherent) was used for excitation of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TCRs (or CD3ζ-GFP or ZAP70-GFP), and a 561 nm Calypso laser (Cobolt) was used for Alexa Fluor 568-labeled TCRs.

SCM used a combination of TIRF detection of TCR or GFP fusions together with wide-field excitation/emission of Quantum dots. Widefield QD images were acquired using a 405/10x excitation filter (Chroma Technology) in a DG-4 Xenon light source (Sutter). TCR and QD fluorescence were split using a DV2 with a 565 nm long-pass dichroic and 520/35m and 605/70m emission filters (Photometrics). Split images were collected using an Evolve an electron-multiplying charged-coupled device (emCCD) in quantitative mode (Photometrics). IRM images were acquired using a 635/20x excitation filter (Chroma Technology), and reflected light was collected onto the long-pass side of the DV2 imaging path. For time lapse image series, image sequences were typically acquired at 1 second intervals.

Scanning angle interference microscopy (SAIM) imaging

N-type [100]-orientation silicon wafers with 1933 nm silicon oxide (Addison Engineering) were cut into ~0.5 cm2 chips using a diamond pen. Chips were cleaned with warm 20% 7× detergent, then washed with copious amounts of 18 MΩ water. After cleaning, chips were placed into wells of an 8-well Nunc Lab-Tek II chambered coverglass. Bilayers were prepared on the chips using the same procedures as for coverslip supported bilayers. To measure bilayer heights, liposomes for supported lipid bilayers were labelled with 200:1 Vybrant DiO lipophilic dye (Molecular Probes) in PBS for 5 minutes, and then applied to the chips. Imaging was performed on an inverted Ti-E Perfect Focus System (Nikon) controlled by Metamorph software, equipped with 488 nm and 561 nm lasers, a motorized laser Ti-TIRF-E unit, a 1.49 NA 100× TIRF objective, emCCDcamera (QuantEM 512; Photometrics), and with a linear glass polarizing filter (Edmunds Optics) in the excitation laser path. Preparation of SAIM calibration wafers, and SAIM imaging and analysis were performed as described previously (35). All images were filtered with a 1 pixel σ Gaussian filter to smooth background noise. For quantitative image analysis, local background subtraction followed by intensity thresholding was used to create whole cell and microcluster masks.

ZAP-70AS Mutations

For 3-MB-PP1 challenge imaging, 2×105 cells were incubated with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1 for 5 minutes at room temperature before introduction to bilayers. Bilayer wells were equilibrated with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1 before imaging. Cells were added to wells, and imaging initiated for a cell as it began interacting with the bilayer.

General Image analysis

All computational image analysis for SCM imaging was performed in Matlab (The Mathworks) and Fiji. Figure images were created by pseudocoloring images as needed in Fiji or in Matlab, then resizing to 600 dpi using bicubic interpolation in Matlab, Fiji or Photoshop (Adobe). Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (Graphpad). Analysis for LLS was performed in Imaris (Bitplane) and Matlab. The unique analysis code has been made available through GitHub and can be found at the following URL: https://github.com/BIDCatUCSF/science-visualizingmicrovillarsearch.

Lattice Light Sheet: Post Processing

Raw data were deconvolved utilizing the iterative Richardson-Lucy deconvolution process with a known point spread function that was recorded for each color prior to the experiment (13). The code for this process was provided by the Betzig lab at Janelia Farms. It was originally written in Matlab (The Mathworks) and ported into CUDA (Nvidia) for parallel processing on the graphics processing unit (GPU, Nvidia GeForce GTX Titan X). A typical sample area underwent 15–20 iterations of deconvolution.

Regions of interest (ROI) within the sampling area were cropped down to size and compressed from 32-bit TIFFs to 16-bit TIFFs using in-house Matlab code to allow immigration into Imaris. Within Imaris, the ROI was reoriented in 3D and the plane of interest (POI), such as the immunological synapse, was selectively cropped. The POI was then exported as TIFF files, which were recombined to produce maximum intensity projections (MIPs) at each time point using in-house Matlab code.

Plane of Interest Stabilization

To separate the lateral motion of the T cell from the motion of the surface protrusions, the POI was stabilized to the field of view (FOV) using one of two intensity unweighted center-of-mass calculations performed using in-house Matlab code. In the first method, a binary mask was created of the POI, which was then rounded to offset the effect of small surface protrusions before calculating the average x and y positions. The second method followed the same procedure but included eroding the mask to compensate for larger surface protrusions before calculating the average x and y positions. The evaluation of the method was performed manually before a new image stack was created using the average x and y positions as the center of the FOV. See also Extended Data Fig S1.

Mask Creation

To isolate ROIs for further analysis a non-regularly shaped mask was created to maximize information collection. Within Matlab each frame of the previously stabilized movie was converted to binary using a threshold above background. The image was then thickened to round out surface protrusions extending from the surface in the visualization plane, the holes were filled, and the gaps were closed. The mask was then shrunk by 3–5 pixels to exclude the intensity collected from the cell surface oriented orthogonal to the visualization plane. The final mask consisted only of pixels where the mask was colocalized throughout the entire observation period. See also Extended Data Fig S1.

Surface Dynamics

Calculation of the dynamics of the surface protrusions was performed using in-house Matlab code. The membrane was thresholded by (membrane mean (within the mask area) + 3x standard deviation of the background) at each time point. The resulting binary image was used to determine instantaneous and cumulative surface coverage. To track microvillar protrusion, the “spots” function was used in Imaris, using a target spot size of 0.535 μm, followed by manual validation of spots and automated tracking using a “Brownian” model with a minimum duration above 13.5 seconds and maximum movement of 0.4 μm per timepoint.

Fractal Analysis

The fractal determination and fractal dimensions were calculated using an in-house Matlab script following the “box counting” method as previously described, which was validated using the ImageJ plugin FracLac (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/plugins/fraclac/FLHelp/Introduction.htm). Briefly, a grid with an individual box length L was placed on top of the image. The image was shifted methodically in x and y dimensions to minimize the number of boxes needed to cover the entire active area of the cell. This process was repeated for a range of box lengths. The data are then fit to the equation N = Ce-Fd where N equals the number of boxes needed to cover the image, Fd is the fractal dimension and C is a constant, and e is the size of the box.

TIRF Contact / TCR co-localization

The contact TCR co-location was performed using an in-house Matlab script. Briefly, the contact “footprints” were used as a mask to isolate fluorescence intensity associated with TCRs. The intensity in each TCR “object” was then averaged and plotted in a histogram. A Gaussian distribution curve centered at the background fluorescence median was then overlayed. The contacts that fell within 3 sigma of the Gaussian distribution were then considered TCR−, while the higher intensity contacts were considered TCR+ and the binary representations were split into two separate image stacks.

Track Kymographs

To create kymographs from TCR microcluster tracks, microcluster centroids at each point in the track were converted to pixel indices. The track pixel indices were then used to create horizontal image lines of the TCR and QD605-SA intensity. Image lines at each time point were stacked to create track kymographs in which the horizontal locations represent points along the track and the vertical positions represents time points.

SCM based contact segmentation and analysis

To identify and segment contact regions, the IRM images were first filtered with a high-frequency emphasis filter, then segmented using an active contour to identify the synapse footprint region on the bilayer. Intensity local minima inside the synapse region with intensities less than the median intensity in the synapse region were detected. Each local minimum was dilated with 3-pixel diameter disk structuring element (a cross) and used as a mask input for active contour segmentation of the Qdot image. If the active contour failed to detect a region in the Qdot image, the contour collapsed and the minima was discarded. After independent segmentation of all regions, regions that shared >50% of their area were merged to produce a final segmentation. Pixel indices for identified contact regions that remained after active contour analysis were saved. The centroid and equivalent radius of the contacts were used to create Spots objects in Imaris (Bitplane) for tracking analysis (Supplementary Fig S8).

Contacts, TCR microclusters and ZAP70-GFP microclusters were tracked using the Imaris autoregressive motion-tracking algorithm with a 0.25 μm frame-to-frame distance criterion and 1 frame gap allowance.

Qdot Surface Projections

To generate Qdot image surface projections (e.g. Movie S9), images were first intensity normalized, then filtered with a 0.1 μm σ Gaussian filter, and then converted to surfaces. Surfaces were pseudocolored using the “hot” colormap in Matlab. To overlay TCR intensities on the surfaces, a duplicate of the intensity surface was generated, pseudocolored green, and its alpha (opacity) values mapped to the normalized TCR intensity multiplied by 2.

TCR Dwell Time

Within Matlab, using a “rolling sum”, frames of the binary TCR+ and TCR− contacts were summed within an 18.9 second (30 frame) interval.

Statistics

Statistical tests as indicated by figure legends were performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Movie 1. Microvillar dynamics in T cells

Surface projection of an OT-I T cell labeled with anti-CD45-Alexa488 and imaged by LLS microscopy. Time resolution is 2.25 s. For this movie, the cell’s position in space was stabilized using the center of mass (see also Fig S1A).

Movie 2. The immunological synapse formed between a T cell and an APC

This movie shows an IS formed between a T cell and an APC captured by time-lapse LLS microscopy. For synapse side view, the T cell, labeled with anti-CD45-Alexa488, is shown in red; the APC (BMDC), labeled with DiD, is shown in green. The top-right panel shows the en face view of this synapse. The lower-left panel shows a 3D surface of the synapse rendered in Imaris. The lower-right panel shows the synapse with the z scale color coded.

Movie 3. Comparison of dynamic behaviors of TCR+ and TCR− contacts

Overlay of the TCR+ contact population (shown in yellow) with the TCR− contact population (shown in red), as defined in Fig 4F. Movie demonstrates the stability of the TCR+ compared to TCR− contacts.

Movie 4. SCM time-lapse imaging of IS contacts and TCRs of a ZAP70(AS)/OT-I T cell during 3-MB-PP1 treatment

Time-lapse movie of QD605-streptavidin SCM and TCR TIRF images of a ZAP70(AS)/OT-I synapse formed on an activating bilayer after treatment with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1 to inhibit ZAP70(AS). Top-to-bottom: TCR TIRF, QD605-streptavidin SCM and IRM images. TCRs were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated H57-597 anti-TCRβ. Movie region measures 14 μm × 14 μm. Total time elapsed is 257 seconds. Original acquisition rate was 1 frame/sec. Movie is played at 12 frames/sec (12× real time).

Movie 5. SCM time lapse imaging of IS contacts and TCRs during Latrunculin B challenge

Time-lapse movie created from QD605-streptavidin SCM and TCR TIRF images of an OT-I synapse formed on an activating bilayer. Top-to-bottom: QD605-streptavidin, IRM and TCR images. TCRs were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated H57-597 anti-TCRβ. Movie region measures 17.5 μm × 17.5 μm. Total time elapsed is 4 minutes. Latrunculin was added after ~45 seconds. Original acquisition rate was 1 frame/sec. Movie is played at 12 frames/sec (12× real time).

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the NIH grant AI052116 to MFK and NSF Graduate Research Fellowship grant 1650113 to CB. FB acknowledges the Spanish Ministry MINECO (Grant: CGL2016-78156-C2-1-R). We are grateful to Lauren Richie-Ehrlich for the gift of pIB2-Zap70-GFP, and A.Weiss and B. Au-Yeung for the gift of ZAP70(AS)/OTI mice and the NIH Tetramer Facility at Emory University for the monobiotinylated pMHC monomer reagents. The data reported in this manuscript are in the main paper and in the supplementary materials. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References and Notes

- 1.Gerard A, Patino-Lopez G, Beemiller P, Nambiar R, Ben-Aissa K, Liu Y, Totah FJ, Tyska MJ, Shaw S, Krummel MF, Detection of Rare Antigen-Presenting Cells through T Cell-Intrinsic Meandering Motility, Mediated by Myo1g. Cell 158, 492 (July 31, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Springer TA, Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346, 425 (August 02, 1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell GI, Dembo M, Bongrand P, Cell adhesion. Competition between nonspecific repulsion and specific bonding. Biophys J 45, 1051 (June, 1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glauert AM, Sanderson CJ, The mechanism of K-cell (antibody-dependent) mediated cytotoxicity. III. The ultrastructure of K cell projections and their possible role in target cell killing. Journal of cell science 35, 355 (February, 1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Andrian UH, Hasslen SR, Nelson RD, Erlandsen SL, Butcher EC, A central role for microvillous receptor presentation in leukocyte adhesion under flow. Cell 82, 989 (September 22, 1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dustin ML, Cooper JA, The immunological synapse and the actin cytoskeleton: molecular hardware for T cell signaling. Nature Immunology 1, 23 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunnell SC, Kapoor V, Trible RP, Zhang W, Samelson LE, Dynamic actin polymerization drives T cell receptor-induced spreading: a role for the signal transduction adaptor LAT. Immunity 14, 315 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stinchcombe JC, Bossi G, Booth S, Griffiths GM, The immunological synapse of CTL contains a secretory domain and membrane bridges. Immunity 15, 751 (November, 2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunnell SC, Hong DI, Kardon JR, Yamazaki T, McGlade CJ, Barr VA, Samelson LE, T cell receptor ligation induces the formation of dynamically regulated signaling assemblies. J Cell Biol 158, 1263 (September 30, 2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueda H, Morphew MK, McIntosh JR, Davis MM, CD4+ T-cell synapses involve multiple distinct stages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 17099 (October 11, 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sage PT, Varghese LM, Martinelli R, Sciuto TE, Kamei M, Dvorak AM, Springer TA, Sharpe AH, Carman CV, Antigen recognition is facilitated by invadosome-like protrusions formed by memory/effector T cells. J Immunol 188, 3686 (April 15, 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierres A, Monnet-Corti V, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P, Do membrane undulations help cells probe the world? Trends in cell biology 19, 428 (September, 2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen BC, Legant WR, Wang K, Shao L, Milkie DE, Davidson MW, Janetopoulos C, Wu XS, Hammer JA 3rd, Liu Z, English BP, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Romero DP, Ritter AT, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Fritz-Laylin L, Mullins RD, Mitchell DM, Bembenek JN, Reymann AC, Bohme R, Grill SW, Wang JT, Seydoux G, Tulu US, Kiehart DP, Betzig E, Lattice light-sheet microscopy: imaging molecules to embryos at high spatiotemporal resolution. Science 346, 1257998 (October 24, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MJ, Wei SH, Parker I, Cahalan MD, Two-photon imaging of lymphocyte motility and antigen response in intact lymph node. Science 296, 1869 (June 7, 2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krummel MF, Bartumeus F, Gerard A, T cell migration, search strategies and mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 193 (March, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seuront L, Fractals and Multifractals in Ecology and Aquatic Sciences. (CRC Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnsley MF, Fractals Everywhere. (Academic Press, New York, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendez V, Campos D, Bartumeus F, Stochastic Foundations in Movement Ecology: Anomalous diffusion, invasion fronts and random searches. (Springer Verlag, Gerlin, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beemiller P, Jacobelli J, Krummel MF, Integration of the movement of signaling microclusters with cellular motility in immunological synapses. Nat Immunol, (July 1, 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML, The immunological synapse: A molecular machine that controls T cell activation. Science 285, 221 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung Y, Riven I, Feigelson SW, Kartvelishvily E, Tohya K, Miyasaka M, Alon R, Haran G, Three-dimensional localization of T-cell receptors in relation to microvilli using a combination of superresolution microscopies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, E5916 (October 4, 2016, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alakoskela JM, Koner AL, Rudnicka D, Kohler K, Howarth M, Davis DM, Mechanisms for size-dependent protein segregation at immune synapses assessed with molecular rulers. Biophys J 100, 2865 (June 22, 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varma R, Campi G, Yokosuka T, Saito T, Dustin ML, T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity 25, 117 (July, 2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Au-Yeung BB, Melichar HJ, Ross JO, Cheng DA, Zikherman J, Shokat KM, Robey EA, Weiss A, Quantitative and temporal requirements revealed for Zap70 catalytic activity during T cell development. Nat Immunol 15, 687 (July, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumari S, Depoil D, Martinelli R, Judokusumo E, Carmona G, Gertler FB, Kam LC, Carman CV, Burkhardt JK, Irvine DJ, Dustin ML, Actin foci facilitate activation of the phospholipase C-gamma in primary T lymphocytes via the WASP pathway. eLife 4, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritter Alex T., Asano Y, Stinchcombe Jane C., Dieckmann NMG, Chen B-C, Gawden-Bone C, van Engelenburg S, Legant W, Gao L, Davidson Michael W., Betzig E, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Griffiths Gillian M., Actin Depletion Initiates Events Leading to Granule Secretion at the Immunological Synapse. Immunity 42, 864 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Germain RN, T-cell signaling: the importance of receptor clustering. Curr Biol 7, R640 (October 1, 1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su X, Ditlev JA, Hui E, Xing W, Banjade S, Okrut J, King DS, Taunton J, Rosen MK, Vale RD, Phase separation of signaling molecules promotes T cell receptor signal transduction. Science 352, 595 (April 29, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyons DS, Lieberman SA, Hampl J, Boniface JJ, Chien Y.-h., Berg LJ, Davis MM A TCR binds to antagonist ligands with lower affinities and faster dissociation rates than to agonists. Immunity 5, 53 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang VT, Fernandes RA, Ganzinger KA, Lee SF, Siebold C, McColl J, Jonsson P, Palayret M, Harlos K, Coles CH, Jones EY, Lui Y, Huang E, Gilbert RJ, Klenerman D, Aricescu AR, Davis SJ, Initiation of T cell signaling by CD45 segregation at ‘close contacts’. Nat Immunol 17, 574 (May, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashimoto-Tane A, Sakuma M, Ike H, Yokosuka T, Kimura Y, Ohara O, Saito T, Micro-adhesion rings surrounding TCR microclusters are essential for T cell activation. J Exp Med 213, 1609 (July 25, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lillemeier BF, Mortelmaier MA, Forstner MB, Huppa JB, Groves JT, Davis MM, TCR and Lat are expressed on separate protein islands on T cell membranes and concatenate during activation. Nat Immunol 11, 90 (January, 2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L, A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593 (September, 2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerard A, Khan O, Beemiller P, Oswald E, Hu J, Matloubian M, Krummel MF, Secondary T cell-T cell synaptic interactions drive the differentiation of protective CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 14, 356 (April, 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paszek MJ, DuFort CC, Rubashkin MG, Davidson MW, Thorn KS, Liphardt JT, Weaver VM, Scanning angle interference microscopy reveals cell dynamics at the nanoscale. Nat Methods 9, 825 (August, 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1. Microvillar dynamics in T cells

Surface projection of an OT-I T cell labeled with anti-CD45-Alexa488 and imaged by LLS microscopy. Time resolution is 2.25 s. For this movie, the cell’s position in space was stabilized using the center of mass (see also Fig S1A).

Movie 2. The immunological synapse formed between a T cell and an APC

This movie shows an IS formed between a T cell and an APC captured by time-lapse LLS microscopy. For synapse side view, the T cell, labeled with anti-CD45-Alexa488, is shown in red; the APC (BMDC), labeled with DiD, is shown in green. The top-right panel shows the en face view of this synapse. The lower-left panel shows a 3D surface of the synapse rendered in Imaris. The lower-right panel shows the synapse with the z scale color coded.

Movie 3. Comparison of dynamic behaviors of TCR+ and TCR− contacts

Overlay of the TCR+ contact population (shown in yellow) with the TCR− contact population (shown in red), as defined in Fig 4F. Movie demonstrates the stability of the TCR+ compared to TCR− contacts.

Movie 4. SCM time-lapse imaging of IS contacts and TCRs of a ZAP70(AS)/OT-I T cell during 3-MB-PP1 treatment

Time-lapse movie of QD605-streptavidin SCM and TCR TIRF images of a ZAP70(AS)/OT-I synapse formed on an activating bilayer after treatment with 10 μM 3-MB-PP1 to inhibit ZAP70(AS). Top-to-bottom: TCR TIRF, QD605-streptavidin SCM and IRM images. TCRs were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated H57-597 anti-TCRβ. Movie region measures 14 μm × 14 μm. Total time elapsed is 257 seconds. Original acquisition rate was 1 frame/sec. Movie is played at 12 frames/sec (12× real time).

Movie 5. SCM time lapse imaging of IS contacts and TCRs during Latrunculin B challenge

Time-lapse movie created from QD605-streptavidin SCM and TCR TIRF images of an OT-I synapse formed on an activating bilayer. Top-to-bottom: QD605-streptavidin, IRM and TCR images. TCRs were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated H57-597 anti-TCRβ. Movie region measures 17.5 μm × 17.5 μm. Total time elapsed is 4 minutes. Latrunculin was added after ~45 seconds. Original acquisition rate was 1 frame/sec. Movie is played at 12 frames/sec (12× real time).