Abstract

Phylogenetic relationships among subgroups of cockroaches and termites are still matters of debate. Their divergence times and major phenotypic transitions during evolution are also not yet settled. We addressed these points by combining the first nuclear phylogenomic study of termites and cockroaches with a thorough approach to divergence time analysis, identification of endosymbionts, and reconstruction of ancestral morphological traits and behaviour. Analyses of the phylogenetic relationships within Blattodea robustly confirm previously uncertain hypotheses such as the sister-group relationship between Blaberoidea and remaining Blattodea, and Lamproblatta being the closest relative to the social and wood-feeding Cryptocercus and termites. Consequently, we propose new names for various clades in Blattodea: Cryptocercus + termites = Tutricablattae; Lamproblattidae + Tutricablattae = Kittrickea; and Blattoidea + Corydioidea = Solumblattodea. Our inferred divergence times contradict previous studies by showing that most subgroups of Blattodea evolved in the Cretaceous, reducing the gap between molecular estimates of divergence times and the fossil record. On a phenotypic level, the blattodean ground-plan is for egg packages to be laid directly in a hole while other forms of oviposition, including ovovivipary and vivipary, arose later. Finally, other changes in egg care strategy may have allowed for the adaptation of nest building and other novelties.

Keywords: isoptera, sociality, maternal care, transcriptomes, systematics, palaeontology

1. Background

A major revelation of systematic entomology in the past decades was the finding that termites (Isoptera) are nested within cockroaches [1,2]. Together, they form the clade Blattodea with approximately 7500 described species [3]. As members of this group are among major dead-wood decomposers and global pests, Blattodea are considered to be ecologically and economically important on the local and global scale; they are important components of many ecosystems, and their dead-wood processing has measurable effects on the global climate, e.g. [4,5].

Although many aspects of Blattodea biology such as morphology [2,6], palaeontology [7,8], biogeography [9], physiology [4,10], and other life-history aspects [4] have been studied, there still remain various open questions. Resolving the phylogeny of Blattodea is of primary concern in this respect because it is the scaffolding for a broader understanding of their evolutionary history.

There is consensus on some phylogenetic relationships within Blattodea. Most studies agree that Blattodea is divided into three monophyletic groups: Blattoidea, Corydioidea, and Blaberoidea. However, relationships among these three groups remain unresolved. Uncertainty on these ancient relationships affects our capacity to address several evolutionary questions, such as the ancestral mode of wing folding and egg deposition. A similar case regards the sister-group to the clade uniting Cryptocercus and termites. This strongly supported clade is characterized by wood-feeding and social behaviour [1,2,9]. However, the sister-group to this clade, and with it the evolutionary precursors to sociality and wood-feeding, are unknown. Previous studies proposed Lamproblatta, Blattidae, Tryonicidae, Anaplectidae, or a combination of these [9,11,12]. Tryonicidae comprises some wood-feeding species [13], so its position relative to Cryptocercus and termites could elucidate the origin of traits related to xylophagy [11,13]. Yet, Lamproblatta spp. share some morphological (e.g. derived genital sclerotizations) and behavioural (e.g. ootheca laying sequence) traits with Cryptocercus [2,14], but their diet is not xylophagous [15].

Beyond phylogenetic relationships, the timing of the origin of major clades in Blattodea is even more debated [9,11,12,16]. There is a huge gap between the fossil record and the ages that molecular-based divergence time studies propose for Blattodea, an issue admittedly common to many taxa, e.g. [17]. While the results of molecular divergence time analyses suggest that Blattodea is at least 240–180 million years (Myr) old [16], the oldest described crown-Blattodea are approximately 139 Myr old termite fossils [18]. Furthermore, the earliest fossil occurrences of subgroups within Blattodea, such as that of putative Blaberidae in the Palaeogene (66–23 Ma; e.g. [19]), strongly contrasts with dating studies that propose a Cretaceous (145–66 Myr) [9,11,16] or even Jurassic (201–145 Myr) [12] origin.

Finally, crown-Blattodea are relatively young [8,18] compared to the many more ancient insect groups, e.g. beetles, wasps, or dragonflies [20]. However, cockroach-like animals were some of the most abundant animals in Carboniferous ‘coal’ swamps [18]. The positions of these so-called ‘roachoids’ and other controversial fossils are debated. While morphological evidence is needed to determine their precise placement [8,18], improved and reliable divergence time estimates could rule out some proposed positions, e.g. as stem or crown-Blattodea.

Resolving the phylogeny of Blattodea has specific implications for understanding evolution in sociality, morphology, diet, endosymbiosis, or egg laying strategies—aspects that remain controversial or poorly understood in these insects. Social behaviour evolved in a full spectrum ranging from solitary, to aggregating, to biparental care, and to eusociality with a complex caste system [4,21]. Additionally, cockroaches protect their offspring by laying eggs in specialized egg packages, so-called oothecae, which are dropped, buried, or carried around. Evolution of egg incubation strategies in Blattodea resulted in ovipary, ovovivipary, and full vivipary [4,14]. Adaptation to novel diets has also driven Blattodea's evolution. Most Blattodea are omnivorous detritus feeders [4], a diet with unpredictable and variable nutrient quality. Blattodea's coevolution with the endosymbiont Blattabacterium assist them in coping with this challenge (e.g. [22,23]). This symbiosis was lost at least twice in Blattodea [23] but many lineages have not been surveyed.

We address the above issues in an integrative way by combining the largest available phylogenomic dataset (comprising on average 2370 protein-coding nuclear single-copy genes for 66 species including all major groups of Blattodea except Anaplectidae) with a thorough dating approach and additional analyses related to endosymbionts, morphology, and social behaviour.

2. Methods

(a). Taxon sampling, sequencing, and data processing

We sequenced transcriptomes of 31 species representing all major lineages of Blattodea (except Anaplectidae) and combined these with transcriptome data of 14 Blattodea and 21 outgroup representatives published by Misof et al. [20] and Wipfler et al. [24]. RNA extraction, cDNA library generation, and paired-end sequencing on Illumina HiSeq 2000 platforms were performed within the 1KITE project, www.1kite.org, see also [20]. Details on sample origin, taxonomic affiliation, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession numbers, wet-laboratory procedures, sequencing and data processing, assembly, contaminant removal, alignment and alignment masking, protein domain identification, and further dataset generation are provided in electronic supplementary material, S1.1. For phylogenetic inference, we optimized and analysed datasets for 66 taxa comprising on average 2370 identified nuclear protein-coding single-copy genes. The final optimized datasets comprised (i) a full nucleotide (nt) dataset including only second codon positions and spanning more than one million sites (1 205 322 nt positions) and (ii) a decisive (sensu [25]) amino acid (aa) dataset spanning over half a million sites (585 040 aa positions). Please refer to electronic supplementary material, S1.1 for details.

(b). Phylogenetic inference and topology testing

We inferred phylogenetic trees with a maximum-likelihood (ML) approach as implemented in iq-tree (v. 1.4-1.6) [26,27] using the decisive aa dataset (592 partitions of 71 126 amino acid sites) and the full nt dataset (1546 partitions). For details on optimizing partition schemes and selecting substitution models, see electronic supplementary material, S1.2. The best tree was inferred from each alignment through 50 independent searches with random starting trees. Support was estimated through non-parametric bootstrapping and bootstrap convergence was assessed a posteriori using the default setting of the autoMRE stopping criterion [28] as implemented in RAxML v. 8 [29]. The possibility of rogue taxon placement was statistically tested using RogueNaRok [30].

The position recovered for Anallacta (as sister-group to Pseudophyllodromiinae) is not in agreement with its morphology-based classification (belonging to Blattellinae). Thus, we further excluded the possibility of erroneous identification or contamination during wet-laboratory procedures by verifying its identity via DNA genetic barcoding and comparative morphology (for details, see electronic supplementary material, S1.3). This confirmed our original identification.

Statistical support for possible alternative topologies was examined for the aa dataset using the approximately unbiased test (AU test; [31]) as implemented in iq-tree. In addition, we checked for hidden and putative confounding signal with respect to the position of Lamproblatta and Corydioidea with Four-cluster Likelihood Mapping (FcLM; [32]), applying the procedure detailed in [33] for the aa dataset, see [20] for a rationale. Details of phylogenetic inference, bootstrap, bootstrap convergence, analyses for rogue taxa, and all topology tests are given in electronic supplementary material, S1.2 and S1.4.

(c). Divergence time estimation

We surveyed the fossil record and identified nine fossils as valid for time-calibration of Blattodea and outgroup clades strictly following the best practices of fossil calibration [34], see also electronic supplementary material, S2. Selected fossils were: Protelytron permanium, Raphogla rubra, Alexrasnia rossica, Juramantophasma sinica, Qilianiblatta namurensis, ‘Gyna’ obesa, Cretaholocompsa montsecana, Valditermes brenanae, and Archeorhinotermes rossi (details including authors are provided in electronic supplementary material, figure S5 and table S8). The rationale for each fossil used is provided in electronic supplementary material, S2.1 and summarised in table S8. The ages of above fossils were used as soft minimum bounds for nine nodes on the tree. The age of Rhynie chert (412 Myr) was used as the hard maximum bound for all calibrations, except for one (Archeorhinotermes rossi with soft maximum at 237 Myr; see electronic supplementary material, S1.5 for justification). We estimated divergence times with the software mcmctree as implemented in Paml v. 4.9 g [35]. Providing our best ML tree from the decisive aa dataset as a fixed input topology, we ran divergence time analysis using (1) a reduced matrix of our decisive aa dataset, containing only aa sites that were unambiguous for at least 95% of taxa (hereafter called the ‘reduced’ dataset) and (2) the decisive aa dataset (hereafter called the ‘unreduced’ dataset). Divergence time analyses were performed on both datasets to examine whether missing data had an impact on estimated divergence times. After generation of Hessian matrices with Codeml, we performed four independent runs for each dataset under the independent rates clock model using uniform priors. We ensured all runs had an effective sample size of more than 200 and converged. Detailed settings, convergence plots, further quality control analyses, and detailed results are provided in electronic supplementary material, S1.5. In the text, we report estimated mean divergence times with half the width of the 95% confidence interval after a ‘±’ sign.

(d). Analysis of morphological evolution and Blattabacterium

We investigated the presence of endocellular mutualists Blattabacterium via a reciprocal BLAST approach [36]. We first identified candidate Blattabacterium transcripts by differentiating insect hosts and other non-target symbiont taxa via compiling reference sequences from a wide variety of species and filtering out all best BLAST hits from non-target taxa. We then extracted sequences attributed to Blattabacterium by our reference BLAST runs and searched them against the entire NCBI nt database. Taxa with transcripts matching Blattabacterium were counted as having the endosymbionts. Additional details are given in electronic supplementary material, S1.6.

We tabulated 20 morphological and behavioural characters from previous publications [2,11,14,37]. Their most parsimonious ancestral states were inferred using the best ML tree derived from the decisive aa dataset and Mesquite v. 3.3 [38]. We also inferred posterior probability of ancestral states for four of the 20 characters using a Bayesian stochastic character mapping method [39]. Details are provided in electronic supplementary material, S3.

(e). Terminology and taxonomy

We chose a standard set of names to simplify the discussion of phylogenetic relationships and to clarify potentially ambiguous names, see electronic supplementary material, S4. We propose new taxon names for selected clades that are strongly supported in our analyses.

3. Results and discussion

(a). Phylogenetic relationships

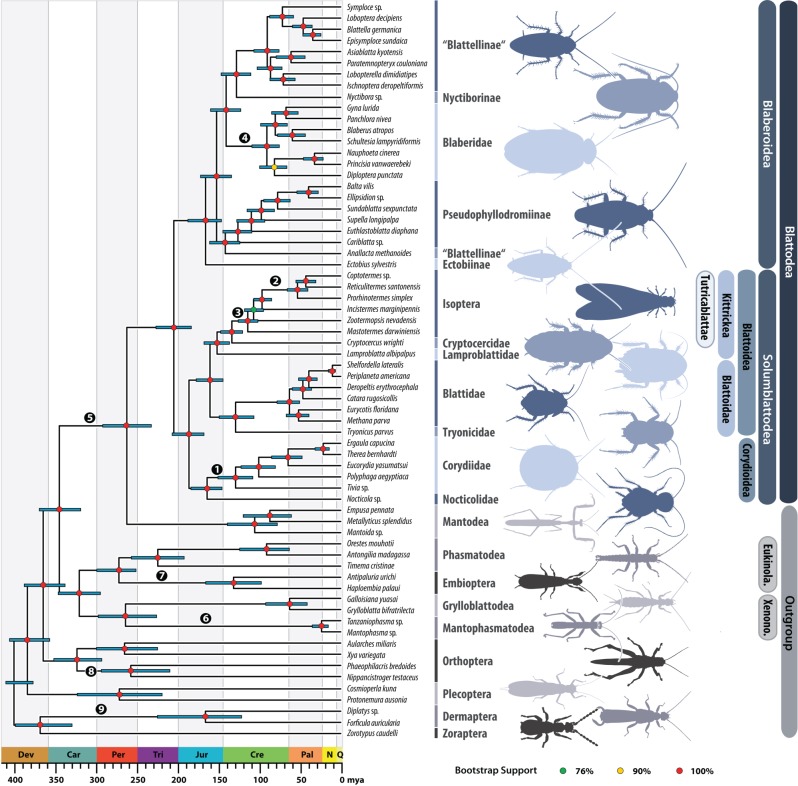

The tree topology recovered from the decisive aa data (figure 1) was congruent with the tree inferred from the full nt dataset including second codon positions only (electronic supplementary material, S1 and figure S3) except for the positions of Mastotermes and Zootermopsis. All other clades in the decisive aa tree had maximal bootstrap support (BS), except for the clade Diploptera + Oxyhaloinae (90% BS). All but one (see below) additional topology test (electronic supplementary material, S1.4; table S7 and figure S4) also gave maximal support for the decisive aa tree topology (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time-calibrated phylogeny of Blattodea. Topology obtained from ML analysis of the decisive amino acid (aa) dataset (585 040 aa positions). Coloured circles represent BS support. Node dates (posterior mean) were inferred using the decisive aa dataset reduced to sites containing 95% or more data completeness, and nine exhaustively vetted fossil calibrations. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Fossils used for calibrations indicated as numbers in black circles are: 1: Cretaholocompsa montsecana; 2: Archeorhinotermes rossi; 3: Valditermes brenanae; 4: ‘Gyna’ obesa; 5: Qilianiblatta namurensis; 6: Juramantophasma sinica; 7: Alexarasnia rossica; 8: Raphogla rubra; 9: Protelytron permianum; see also electronic supplementary material, table S8. Abbreviations: ‘Eukinola.’ = Eukinolabia and ‘Xenono.’ = Xenonomia.

Our results clearly support monophyletic Dictyoptera and Blattodea, with termites + Cryptocercus nested within Blattoidea (figure 1). We also recover Blaberoidea and Blaberidae as monophyletic. The high BS, in combination with FcLM and AU tests, show little conflicting signal in the dataset.

Within Blattodea, we find strong support for Blaberoidea being sister to a clade comprising Corydioidea and Blattoidea (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, S1.4). These results agree with the topologies found in previous studies [11,12,37] (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, S1.4), but refute others that have hypothesized that Corydioidea (e.g. [1,16]) or Blattoidea [9] form the sister-group to remaining Blattodea. Based on strong molecular support for this clade in combination with multiple synapomorphies in sexual morphology, we coin the term Solumblattodea for Blattoidea + Corydioidea (see electronic supplementary material, S4 for full systematic treatment and morphological evidence).

Within Blaberoidea, we retrieve a topology not previously recovered by any study, but all relationships are strongly supported by our data (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, S1.4). We support Ectobius as sister to all other Blaberoidea [16]. Blattellinae and Nyctiborinae (see [7] and references therein) form the sister-group to Blaberidae [1,2] (morphological arguments provided in [2]). Our study corroborates the hypotheses of [9] that Blattellinae is polyphyletic with respect to Anallacta. This is in contrast to [40] in which Anallacta was placed within Blattellinae based on morphological characters. While Blattellinae and Anallacta both have hooked genital phallomere on the left side, other genital morphological characters (shape of L3d and R3d) support our results of Anallacta with Pseudophyllodromiinae (see electronic supplementary material, S1.3 for further details). Our topology within Corydioidea (figure 1) is congruent with previous studies [9,11,12,16].

Within Blattoidea, our phylogenomic analysis agrees with the topology of Legendre et al. [12] in showing that the neotropical genus Lamproblatta is sister to Cryptocercus + Isoptera and forms the sister-group to Tryonicus + Blattidae. AU and FcLM tests provide further strong support for these relationships (see electronic supplementary material, S1.4). We formally give the name Kittrickea to the clade (Lamproblattidae + (Cryptocercus + Isoptera)), honouring Frances Ann McKittrick who first proposed this relationship [41] (see electronic supplementary material, S4 for full systematic treatment and synapomorphies).

The sister-group relationship between Cryptocercus and Isoptera is well supported (e.g. [1,2]). Our comprehensive phylogenomic dataset, independent from previous ones, confirms Cryptocercus + Isoptera with unambiguous support. We thus propose the name Tutricablattae (i.e. cockroaches with childcare; electronic supplementary material, S4) for this clade.

The only disagreement between the trees inferred from the decisive aa and full nt datasets is the sister relationship of Mastotermes to all other termites in contrast to Zootermopsis as sister to all other termites (latter inferred from the nt dataset). Both relationships were not rejected by an AU test (electronic supplementary material, S1.4 and table S7). Still, we consider the tree inferred from the decisive aa dataset and the inferred sister relationship of Mastotermes to all other termites as more reliable because of the decisive aa datasets lower proportion of missing data and greater sequence overlap among taxa of interest (see rationale in electronic supplementary material, S1.1 section ‘optimizing datasets’). Furthermore, the position of Mastotermes as sister to all remaining termites (figure 1) is widely accepted and supported by many lines of evidence (e.g. [1,2,9]).

Within Blattidae, we support monophyletic Polyzosteriinae and (Blattinae + Catara rugosicollis) [9,14], thus contradicting the hypothesis of Legendre et al. [12] whose topology is more congruent with biogeographic distribution. Under the latter scenario [12], neotropical Polyzosteriinae are monophyletic while old-world Archiblattinae and Blattinae are closely related to Polyzosteriinae from Oceania. Future studies with larger taxon sampling (i.e. Duchailluiinae, Pelmatosilpha, Angusticonicus s.l., other Polyzosteriinae) would be required to finally resolve this question.

(b). Evolutionary history of Blattodea

(i). The timing of Blattodea's origins (electronic supplementary material, S1.6)

In agreement with [12] we vetted fossils according to the criteria of [34]. Additionally, we provide the first approach to divergence time inference of Blattodea that applies (i) a large selection of outgroup fossil calibrations, (ii) considers evolutionary rates inferred from transcriptome-scale sampling of nuclear loci (electronic supplementary material, S1.5), and (iii) accounts for the effect of missing data on inferred ages. Our analyses showed that excluding sites with less than 95% of terminal taxa resulted in slightly older mean inferred ages (about 5–10 Myr; electronic supplementary material, table S9). This discrepancy is within our margin of error (95% confidence ranges) and similar to discrepancies in other studies [42]. Consequently, missing data inherent in our datasets had a trivial effect on our estimated divergence times.

Inferred from the reduced decisive aa dataset, Blattodea and Mantodea split 263 (±30) million years ago (MYA) and crown-Blattodea originated 205 (±21.5) MYA (figure 1). These ages are congruent with all other dated phylogenies except Legendre et al. [12] who estimated these nodes as 30–70 Myr older. This is not unexpected given that Legendre et al. [12] allowed age estimates to be as old as possible to conservatively test controversial fossils, using a very old maximal root age. The comparatively young ages we obtained for stem- and crown-Blattodea are in contrast to the wide-held assumption that these insects have existed since the Carboniferous (approx. 304 MYA). Cockroach-like insects with long ovipositors, so-called ‘roachoids’, occurred in the Carboniferous and Permian (figure 2; e.g. [8,18]). Some of them are likely representatives of stem-Dictyoptera (electronic supplementary material, S2), while the precise phylogenetic position of others remain unresolved. Our divergence time estimates clearly show that modern cockroaches evolved after these ‘roachoids’ with long ovipositors, thus further confirmation that these roachoids are not crown-Dictyoptera (figure 2; further discussed in [7,8]).

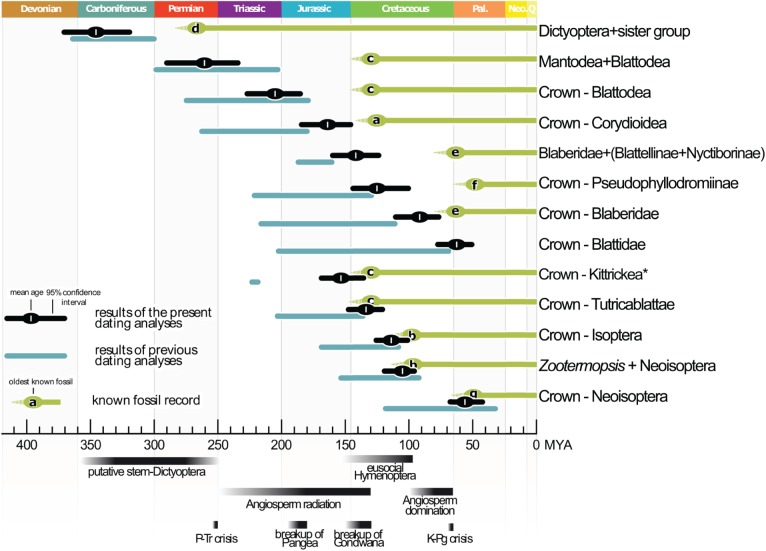

Figure 2.

Comparison of divergence times for selected Blattodea lineages retrieved in our study (black bars) with the fossil record (green bars), selected previous studies (blue bars: [9,11,12,16]) and important historical events as mentioned in the text. a: Cretaholocompsa montsecana, b: Archeorhinotermes rossi, c: Valditermes brenanae, d: Qilianiblatta namurensis, e: Morphna paleo, f: Cariblattoides labandeirai, g: Parastylotermes krishnai. *: Kittrickea was previously only recovered by [12]. Colour gradient bars represent historical events that are fully achieved when the colour is black.

Within crown-Blattodea, our results more sharply contrast other divergence time studies [9,11,12,16] and show that most subgroups are much younger than previously thought. We retrieve a Cretaceous origin for most major splits within Blattodea, as opposed to a Jurassic or Triassic origin (figure 2). The only exceptions are Corydioidea and Kittrickea (Middle or Late Jurassic) and crown-Blattidae (Paleogene). Our divergence time results also strongly decrease, or even bridge, the gaps between the oldest described fossils and molecular age estimates for various subgroups of Blattodea (figure 2).

During the Cretaceous, soil nitrogen levels are thought to have significantly increased [43] as a result of angiosperms dominating the global flora in replacement of Gymnosperms (figure 2) [43]. Blattodea would have both benefited from (through increased available dietary nitrogen) and contributed to (as detritus processors [4]) this macro-ecological shift.

We found that the last common ancestor of the xylophagous taxon Tutricablattae originated 134 (±13.5) MYA on the remnants of Gondwana (figure 2; [9]). Some previous studies gave purported records of fossil termite nests from 181 to 235 MYA, see [44]. However, both the age and attribution of these putative nests to termites has been challenged (e.g. [12]). A Cretaceous origin of termites might correspond with the origin of crown-angiosperms (figure 2), potentially relating to many factors (e.g. increased food availability for termites, opportunity for adaptation, shifts in soil ecology). However, vast uncertainties in their age [45] leave correlations up for debate.

Our analyses clearly date the origin of Neoisoptera, which include the vast majority of termite species, to the beginning of the Palaeogene (53 ± 13 MYA). Our data thus provide strong additional support [16] that this key evolutionary radiation could be correlated with the rise of flowering plants to global dominance, which was completed by the end of the Cretaceous [43] or a competitive release after the K-Pg mass extinction event (figure 2).

Prior to the rise of angiosperms and the associated abundance of available nitrogen, Blattodea evolved unique evolutionary strategies for maintaining internal nitrogen economy by symbiosis with microbes. Most cockroaches are thought to have endocellular symbiotic bacteroids, i.e. Blattabacterium, that provide their hosts with amino acids and recycle nitrogenous waste products into usable nitrogen [10]. We corroborate previous accounts [10,23] in showing that Blattabacterium is absent in Mantodea and present in almost all groups of Blattodea except Euisoptera and Nocticola (see electronic supplementary material, S1.6 for more details). Additionally, we could not determine the presence of Blattabacterium in Diploptera, Tivia, and Lamproblatta—the latter two species with key positions in the tree (i.e. they influence the ancestrally inferred state of Blattabacterium presence; see electronic supplementary material, S3), for which the occurrence of Blattabacterium has not yet been studied. For now, we assume that the symbioses with Blattabacterium evolved once during Blattodea's evolutionary history [23] and that it was lost twice: in Nocticola and again in Euisoptera (electronic supplementary material, S1.6). Further potential losses should be investigated by future studies.

(ii). Sociality and parental care (electronic supplementary material, S3)

Cockroaches and termites show a wide spectrum of social behaviour, ranging from simple brood aggregation to full eusociality in termites. Our divergence time analyses indicate that eusociality, along with the origin of stem-Isoptera, evolved less than 134 (±13.5) MYA. Isoptera may have been the only eusocial organisms for approximately 39 Myr [18] or similar social structures could have evolved earlier in ants and bees (figure 2; [17]). Less complex social structures evolved in the common ancestor of termites and Cryptocercus, and later on in Blaberidae (e.g. [9]). Almost all cockroaches show some form of maternal care [4,14], but this behaviour includes various forms such as protecting eggs, nursing offspring, or nest building. These behaviours strongly differ and are difficult to homologize. Additionally, forms of maternal care are also found in some mantises [46]. Therefore, we refrain from making any statement about the evolutionary origin of maternal care in general and instead discuss specific forms.

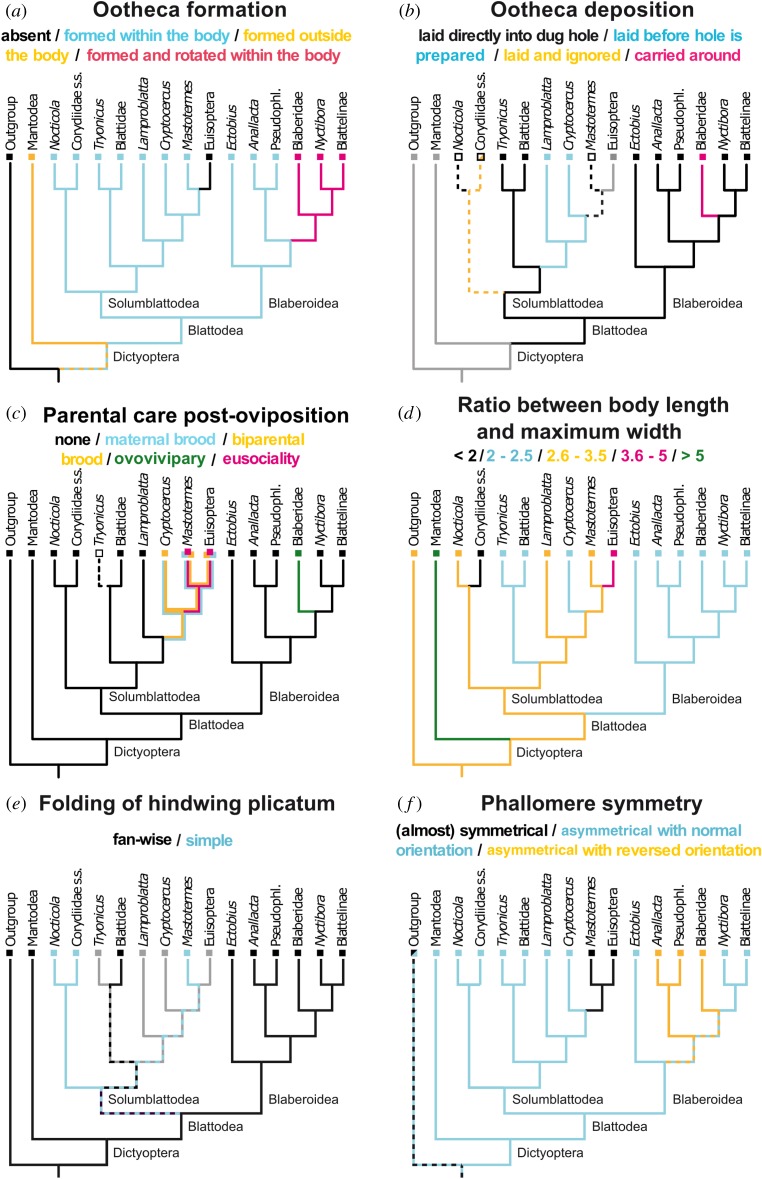

One aspect of maternal care in cockroaches relates to the egg package, i.e. ootheca, which occur in all Dictyoptera except Euisoptera. According to our analyses, this feature was present in the last common ancestor of Dictyoptera and originated between 346 (±25) MYA and 263 (±30) MYA. However, in contrast to mantises, which create oothecae outside their bodies and attach them to substrate (figure 3a), our results suggest that early species of Blattodea produced them internally (figure 3a; and see [8] for discussion). Our ancestral state reconstruction suggests that laying an ootheca in a pre-dug hole is an ancestral trait in Blattodea (figure 3b). This procedure is still found in many Blattidae and Blaberoidea, while it is secondarily modified in others. Corydioidea simply drop their egg case without further care while Kittrickea lay the ootheca before they start to dig the hole [14]. In extant Lamproblatta, the ootheca is left unprotected while the adult digs its cradle but in Tutricablattae, who perform the whole procedure in a woody gallery, this danger is alleviated. The observation of these changes in oothecal care led [14] suggest that these groups might be closely related, which our study strongly supports (electronic supplementary material, S1.4 and figure S4).

Figure 3.

Ancestral state reconstructions of selected traits in the evolutionary history of Blattodea, represented by a simplified tree. Reconstructions of: (a) mode of ootheca formation, (b) ootheca laying behavioural sequence, (c) type of parental care post-oviposition, (d) body shape (length to width ratio), (e) hindwing folding type, and (f) phallomere symmetry. Solidly coloured branches represent the state for that lineage or tip. Dashed branches or no colouration represent uncertain states. States not applicable to the taxon are in grey. Full reconstructions of all traits are given in electronic supplementary material, S3.

Female Solumblattodea can produce oothecae without drastically deforming their bodies due to a valvate subgenital plate. This trait was likely present in the ancestral Blattodea [8] but it was lost among Blaberoidea, which have a simple, unarticulated subgenital plate. Thus, Blaberoidea must deal with the ootheca in other ways. As supported by our ancestral state reconstruction (figure 3a), one novelty in the ancestor of Blaberidae and (Blattellinae + Nyctibora) was the 90° rotation of the laterally flattened ootheca, which better fits in their dorsoventrally flattened bodies. Our retrieved monophyly of this group (figure 1) implies that this trait evolved only once and no reversal occurred in Pseudophyllodromiinae or Ectobiinae, as would be implied with other topologies (e.g. [11,12,16]); although data for Anallacta is lacking). The novelty of rotating the ootheca arose before ovovivipary, i.e. permanent carriage of the ootheca within the brood sac of the female. We found ovovivipary to be plesiomorphic for Blaberidae (figure 3b). These were all a precedent to true vivipary, seen to recently evolve in one genus of Blaberidae (electronic supplementary material, S3).

Post-ovipositional maternal care can manifest as maternal brood care or ovovivipary. Our results indicate that these were not present in the last common ancestor of Blattodea. Instead brood care, including long-lasting biparental brood care, evolved in the last common ancestor of Cryptocercus and Isoptera (figure 3c). In the latter, it occurs among dealates during the early stages of colony foundation [47,48]. A similar form of social behaviour is also reported for some Blaberid cockroaches [4] such as Salganea or Parasphaeria. However, the situation in Cryptocercus + Isoptera differs strikingly from all others by involving proctodeal feeding (figure 3c) [49]. Ovovivipary is only found in Blaberidae cockroaches and possibly Blattella [14].

(iii). Morphological evolution (electronic supplementary material, S3)

Body length-width ratios have been greatly conserved within Blattodea (figure 3d). We reconstructed the ground-plan of Blattodea with a length-width ratio between 2.6 and 3.5, a situation retained in ancestral Solumblattodea (figure 3d). According to our data, Corydiidae sensu stricto became moderately round (ratio < 2 : 1), which was retained in most extant species. Representatives of this group are known to live in xeric habitats [4] in which a round body shape, i.e. a low surface-area volume ratio, would assist with water retention. Among Euisoptera the body shape is even more strongly elongated (ratio 3.6–5.0). This is almost certainly an adaptation to living in enclosed tunnels, a situation found in other wood-eating lineages of Blattodea (e.g. Cyrtotria, Compsagis, Paramuzoa), but possibly has additional biological implications [50].

Two different types of hindwing folding occur among Blattodea: Corydioidea and Mastotermes show a simple folding, while all others have additional fan-wise folds in their anal area (plicatum). Once deployed, a folded plicatum typically has more surface area and is more easily deformed, thus providing more efficient aerofoil. This is perhaps why Rehn [51] assumed that the simple folding observed in Corydioidea, a presumably less functionally efficient configuration, represents the ancestral condition for all Blattodea. However, our analysis contradicts this and shows that the ancestral blattodean folded the plicatum of its hindwing fan-wise (figure 3e).

There were also multiple changes in male-genital phallomere symmetry during the evolution of Blattodea (figure 3f). For instance, we show that Isoptera likely secondarily gained bilateral symmetry in male genitalia and within Blaberoidea two major subgroups exhibit reversed male-genital asymmetry (electronic supplementary material, S3). Additionally, some Ectobiinae and Pseudophyllodromiinae not included in our study exhibit similar changes in symmetry [2]. We therefore cannot clarify the polarity of this character (electronic supplementary material, S3).

We corroborate previous studies [6,18] in showing that the reduction of the median ocellus is an apomorphy of Blattodea (electronic supplementary material S3 and table S12). This challenges the placement of some purported crown-group fossils with three ocelli [7].

4. Conclusion

Our analyses allow for the most comprehensive integrative study of the evolution of Blattodea. Our dataset of nuclear single-copy protein-coding genes provide strong support for many disputed relationships earlier questioned in the phylogeny of Blattodea. Our approach to assessing topological support resolves issues of ambiguous support discussed in other studies [11,12,52], while bringing a new issue to light in the case of Mastotermes and Zootermopsis. Notably, our data strongly supports: Blaberoidea as sister-group to the remaining Blattodea; Lamproblatta being the closest relative to the wood-feeding and social clade Cryptocercus + termites; and Tryonicus forming a clade with Blattidae. Using highly vetted fossil calibrations and genome-scale nuclear data to estimate divergence times, we show that most major groups of Blattodea originated during the Cretaceous (147–66 Myr) and thus arose much later than previously thought. These younger ages narrow the gap between molecular divergence time estimates and the fossil record. Finally, our robust phylogeny also affords us the opportunity to make strong conclusions about phenotypic modifications in Blattodea associated with morphology, and behaviour. We found—among the various forms of social behaviour occurring within Blattodea—that maternal brood care is not part of the Blattodea ground-plan but evolved independently in different subgroups. The ancestral Blattodea protected its egg package by burying it in a pre-dug hole. Modifications of this ground-plan (including ovivivipary and vivipary) occurred within various subgroups. We suggest that the transition from a free-living ancestor to living within wood (in Cryptocercus and termites) could have been partially driven by advantages gained in protection of the ootheca.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to all those who assisted with any aspect of this project, from specimen collection, to molecular laboratory work, to bioinformatics, divergence time estimates, and all our analyses. Specifically we would like to thank Judith Korb, Robert M. Waterhouse, Lars S. Jermiin, Michael Ott, Jörg Bernhardt, Ian Biazzo, Reinhard Predel, Rene Koehler, Philipp Erkeling, Rüdiger Plarre, Geoff Monteith, Apisit Thipaksorn, Akito Kawahara, Hans Pohl, Sven Bradler, Janice Edgerly-Rooks, Makiko Fukui, Dieter Schulten, Shota Shimizu, Romolo Fochetti, Guanliang Meng, Chentao Yang, Klaus Klass, Donald Mullins, Tristan Shanahan, David Hasselhoff, Ekaterina Sidorchuk, Alexander P. Rasnitsyn, Dimitri Shcherbakov, and Peter Vršanský, Mario Dos Reis, Lena Waidele, Manuela Sann, Ondrej Hlinka, the CSIRO HPC team and other colleagues from BGI-Shenzhen contributed to sample and data curation and management. Thanks to BGI-Shenzhen for supporting and funding this study, through the 1KITE initiative.

Data accessibility

Transcriptome sequences: Genbank Umbrella Bioproject ID PRJNA183205, see Supplementary Table S1 for single Bioprojects included in this study. Supplementary data files are available in the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.p5t5gh1 [53].

Authors' contributions

D.A.E., B.W., and S.S. conceived the study. D.A.E., B.W., M.F., J.K., R.M., K.S., and J.L.W. collected or provided samples. A.D., R.S.P., S.L., L.P., X.Z., K.M., and S.S. assembled and processed the transcriptomes. W.T., K.M., and S.S. phylogenetically analysed the transcriptomes and performed topology tests. D.B., A.D., B.M, L.P., M.P., R.S.P., K.M., and S.S. developed scripts, datasets, and programs. D.A.E., B.W., O.B., J.R., T.W., and J.L.W. contributed to compiling fossil calibration choices, with O.B. taking the lead. D.A.E., M.K.K., R.S.P., J.L.W., K.M., and S.S. contributed to dating analyses with M.K.K. and J.L.W. taking the lead. The morphological data matrix was compiled and analysed by D.A.E. and B.W. D.A.E. analysed the transcriptomes for the presence of Blattabacterium. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, with D.A.E., B.W., K.M., and S.S. taking the lead and F.L. providing major revisions.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

D.A.E.: National Science Foundation (award no. 1608559), Rutgers University; B.W.: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (WI 4324/1-1); M.F.: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (JP15J00776); M.K.K.: NSF Career grant no. 1453157; R.M.: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (JP25440201); J.L.W.: NSF Career grant no. 1453157.

References

- 1.Inward D, Beccaloni G, Eggleton P. 2007. Death of an order: a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study confirms that termites are eusocial cockroaches. Biol. Lett. 3, 331–335. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klass K-D, Meier R. 2006. A phylogenetic analysis of Dictyoptera (Insecta) based on morphological characters. Entomologische Abhandlungen 63, 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beccaloni G, Eggleton P. 2013. Order: Blattodea. Zootaxa 3703, 46 ( 10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.10) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell WJ, Roth LM, Nalepa C. 2007. Cockroaches: ecology, behavior and natural history. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bignell DE, Eggleton P. 2000. Termites in ecosystems. In Termites: evolution, sociality, symbioses, ecology (eds Abe T, Bignell DE, Higashi M), pp. 363–387. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wipfler B, Weissing K, Klass KD, Weihmann T. 2016. The cephalic morphology of the American cockroach Periplaneta americana (Blattodea). Arthropod. Syst. Phylogeny 74, 267–297. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evangelista DA, Djernæs M, Kohli MK. 2017. Fossil calibrations for the cockroach phylogeny (Insecta, Dictyoptera, Blattodea), comments on the use of wings for their identification, and a redescription of the oldest Blaberidae. Palaeontol. Electron. 20.3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hörnig MK, Haug C, Schneider JW, Haug JT. 2018. Evolution of reproductive strategies in Dictyopteran insects—clues from ovipositor morphology of extinct roachoids. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 63, 1–24. ( 10.4202/app.00324.2016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourguignon T, et al. 2018. Transoceanic dispersal and plate tectonics shaped global cockroach distributions: evidence from mitochondrial phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1–14. ( 10.1093/molbev/msy013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patino-Navarrete R, Moya A, Latorre A, Pereto J. 2013. Comparative genomics of Blattabacterium cuenoti: the frozen legacy of an ancient endosymbiont genome. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 351–361. ( 10.1093/gbe/evt011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djernæs M, Klass KD, Eggleton P. 2015. Identifying possible sister groups of Cryptocercidae + Isoptera: a combined molecular and morphological phylogeny of Dictyoptera. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 84, 284–303. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legendre F, Nel A, Svenson GJ, Robillard T, Pellens R, Grandcolas P. 2015. Phylogeny of Dictyoptera: dating the origin of cockroaches, praying mantises and termites with molecular data and controlled fossil evidence. PLoS ONE 10, e0130127 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0130127) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murienne J. 2009. Molecular data confirm family status for the Tryonicus–Lauraesilpha group (Insecta: Blattodea: Tryonicidae). Org. Divers. Evol. 9, 44–51. ( 10.1016/j.ode.2008.10.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKittrick FA. 1964. Evolutionary studies of cockroaches. Mem. Cornell Univ. Agric. Exper Station 389, 1–197. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautier J-Y, Deleporte P. 1986. Behavioural ecology of a forest living cockroach, Lamproblatta albipalpus in French Guyana. In Behavioral ecology and population biology (ed. Drickamer L.), pp. 17–22. Toulouse Privat, IEC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Shi Y, Qiu Z, Che Y, Lo N. 2017. Reconstructing the phylogeny of Blattodea: robust support for interfamilial relationships and major clades. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–8. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-04243-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters RS, et al. 2017. Evolutionary history of the Hymenoptera. Curr. Biol. 27, 1013–1018. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimaldi D, Engel MS. 2005. Evolution of the insects, p. 772 New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui Y, Evangelista DA, Béthoux O. 2018. Prayers for fossil mantis unfulfilled: Prochaeradodis enigmaticus Piton, 1940 is a cockroach (Blattodea). Geodiversitas 40, 355–362. ( 10.5252/geodiversitas2018v40a15) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misof B, et al. 2014. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 346, 763–767. ( 10.1126/science.1257570) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korb J, Thorne B. 2017. Sociality in termites. In Comparative social evolution (eds Rubenstein D, Abbot P), pp. 124–152. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokuda G, et al. 2013. Maintenance of essential amino acid synthesis pathways in the Blattabacterium cuenoti symbiont of a wood-feeding cockroach. Biol. Lett. 9, 20121153 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2012.1153) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo N, Bandi C, Watanabe H, Nalepa C, Beninati T. 2003. Evidence for cocladogenesis between diverse Dictyopteran lineages and their intracellular endosymbionts. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 907–913. ( 10.1093/molbev/msg097) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wipfler B, et al. 2019. Evolutionary history of Polyneoptera and its implications for our understanding of early winged insects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. ( 10.1073/pnas.1817794116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dell'Ampio E, et al. 2014. Decisive data sets in phylogenomics: lessons from studies on the phylogenetic relationships of primarily wingless insects. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 239–249. ( 10.1093/molbev/mst196) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ.. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. ( 10.1093/molbev/msu300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TK, Haeseler AV, Jermiin ALS. 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589. ( 10.1038/nmeth.4285) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. 2009. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? In Research in computational molecular biology RECOMB 2009 lecture notes in computer science (eds R Fueda, L Kruuk) Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aberer AJ, Krompass D, Stamatakis A. 2013. Pruning rogue taxa improves phylogenetic accuracy: an efficient algorithm and Webservice. Syst. Biol. 62, 162–166. ( 10.1093/sysbio/sys078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimodaira H. 2002. An approximately unbiased test of phylogenetic tree selection. Syst. Biol. 51, 492–508. ( 10.1080/10635150290069913) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strimmer K, Haeseler AV. 1997. Likelihood-mapping: a simple method to visualize phylogenetic content of a sequence alignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6815–6819. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6815) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sann M, et al. 2018. Phylogenomic analysis of Apoidea sheds new light on the sister group of bees. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 71 ( 10.1186/s12862-018-1155-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parham JF, et al. 2012. Best practices for justifying fossil calibrations. Syst. Biol. 61, 346–359. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syr107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Z. 2007. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591. ( 10.1093/molbev/msm088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 10, 421 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djernæs M, Klass K-D, Picker MD, Damgaard J. 2012. Phylogeny of cockroaches (Insecta, Dictyoptera, Blattodea), with placement of aberrant taxa and exploration of out-group sampling. Syst. Entomol. 37, 65–83. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2011.00598.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. 2017. Mesquite: A modular system for evolutionary analysis.

- 39.Bollback JP. 2006. SIMMAP: stochastic character mapping of discrete traits on phylogenies. BMC Bioinf. 7, 88 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-7-88) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grandcolas P. 1996. The phylogeny of cockroach families: a cladistic appraisal of morpho-anatomical data. Can. J. Zool. 74, 508–527. ( 10.1139/z96-059) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKittrick FA. 1965. A contribution to the understanding of cockroach-termite affinities. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 58, 18–22. ( 10.1093/aesa/58.1.18) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng Y, Wiens JJ. 2015. Do missing data influence the accuracy of divergence-time estimation with BEAST? Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 85, 41–49. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berendse F, Scheffer M. 2009. The Angiosperm radiation revisited, an ecological explanation for Darwin's ‘abominable mystery’. Ecol. Lett. 12, 865–872. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01342.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Genise JF. 2005. Comment–Advanced early Jurassic termite (Insecta: Isoptera) nests: evidence from the Clarens Formation in the Tuli Basin, Southern Africa (Bordy et al. 2004). Palaios 20, 303–308. ( 10.2110/palo.2004.p05-C01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barba-Montoya J, Reis MD, Schneider H, Donoghue PCJ, Yang Z. 2018. Constraining uncertainty in the timescale of Angiosperm evolution and the veracity of a Cretaceous terrestrial revolution. New Phytol. 218, 819–834. ( 10.1111/nph.15011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilbert JD, Manica A. 2015. The evolution of parental care in insects: a test of current hypotheses. Evolution 69, 1255–1270. ( 10.1111/evo.12656) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson JAL, Okot-Kotber BM, Noirot C. 1985. Caste differentiation in social insects. Oxford, UK: Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nutting W. 1969. Flight and colony foundation. In Biology of termites I (eds Krishna K, Weesner FM), pp. 233–282. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nalepa CA. 1994. Nourishment and the origin of termite eusociality. In Nourishment and evolution in insect societies (eds Hunt J, Nalepa CA), pp. 57–104. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nalepa CA. 2011. Body size and termite evolution. Evolutionary Biology 38, 243–257. ( 10.1007/s11692-011-9121-z). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rehn JWH. 1951. Classification of the Blattaria as indicated by their wings (Orthoptera). Mem. Am. Entomol. Soc. 14, 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evangelista D, Thouzé F, Kohli MK, Lopez P, Legendre F. 2018. Topological support and data quality can only be assessed through multiple tests in reviewing Blattodea phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 128, 112–122. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evangelista DA, et al. 2019. Data from: An integrative phylogenomic approach illuminates the evolutionary history of cockroaches and termites (Blattodea) Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.p5t5gh1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Evangelista DA, et al. 2019. Data from: An integrative phylogenomic approach illuminates the evolutionary history of cockroaches and termites (Blattodea) Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.p5t5gh1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Transcriptome sequences: Genbank Umbrella Bioproject ID PRJNA183205, see Supplementary Table S1 for single Bioprojects included in this study. Supplementary data files are available in the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.p5t5gh1 [53].