Abstract

When sitting and walking, the feet of wandering spiders reversibly attach to many surfaces without the use of gluey secretions. Responsible for the spiders' dry adhesion are the hairy attachment pads that are built of specially shaped cuticular hairs (setae) equipped with approximately 1 µm wide and 20 nm thick plate-like contact elements (spatulae) facing the substrate. Using synchrotron-based scanning nanofocus X-ray diffraction methods, combining wide-angle X-ray diffraction/scattering and small-angle X-ray scattering, allowed substantial quantitative information to be gained about the structure and materials of these fibrous adhesive structures with 200 nm resolution. The fibre diffraction patterns showed the crystalline chitin chains oriented along the long axis of the attachment setae and increased intensity of the chitin signal dorsally within the seta shaft. The small-angle scattering signals clearly indicated an angular shift by approximately 80° of the microtrich structures that branch off the bulk hair shaft and end as the adhesive contact elements in the tip region of the seta. The results reveal the specific structural arrangement and distribution of the chitin fibres within the attachment hair's cuticle preventing material failure by tensile reinforcement and proper distribution of stresses that arise upon attachment and detachment.

Keywords: chitin, cuticle, hair, fibre diffraction, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), wide-angle X-ray diffraction/scattering (XRD/WAXS)

1. Introduction

Wandering spiders, such as the large Central American spider Cupiennius salei, are able to climb vertically and walk upside down on smooth and rough surfaces [1–4]. They share this capability with many insects such as flies and beetles. However, some mechanisms underlying the strong adhesion between the animals' feet and a substrate are different in insects and spiders. Insect adhesion relies on capillary forces caused by fluid secretions between their attachment structures and the substrate [5–9]. Wandering spiders are assumed to adhere due to van der Waals forces between their attachment setae and the substrate without additional fluid involved. This mechanism is generally termed dry adhesion and well-studied in the gecko [10–16] and spider [2,17,18] attachment systems. These dry adhesive systems recently have also been the model for many biomimetic structural adhesives [19–29].

However, although some of the artificial adhesive hair-like structures can reach higher adhesive strength than the natural models, particularly on smooth surfaces, the artificial structured adhesives do not reach the performance of their biological prototypes in regard to their durability and their adaptedness to substrates with a wide range of surface properties, such as different roughness or surface energies. One of the reasons might be inhomogeneously distributed materials within the biological models, as previously shown in the wet fibrous attachment system of beetles [30]. For dry fibrous attachment systems, the possible distribution of materials with different mechanical properties has not been examined previously. This is why in this paper the spider attachment hairs were selected as a model system for synchrotron-based X-ray diffraction studies of the materials involved. Since additional fluid interactions can be excluded, the spider setae are also attractive for X-ray in situ examination of the attachment process.

The spider C. salei is a widely studied spider species and has been a model organism for neurobiology, mechanoreception, sensory physiology, biomechanics and its exoskeleton's structure, function and mechanical properties (e.g. [31–34]). During its eight-legged locomotion, C. salei moves the diagonally opposing legs simultaneously. In quickly walking spiders (10 cm s−1), the most prominent ipsilateral (one-sided) sequence of the legs contacting the ground is 4–2–1–3. However, dependent on the actual substrate and velocity, a wide variety of leg movement patterns can be found. Also, the spiders are able to very quickly compensate the loss of legs by adaptation of their gait pattern [31]. It was shown that every single foot of C. salei can provide 12 mN adhesion force in intact eight-legged animals and approximately 35 mN friction force [35].

Apart from attachment hairs, many other, mostly sensory, hair-shaped cuticular structures such as tactile, wind-sensing and proprioreceptive setae of the spider C. salei were previously studied in detail [36–39], pointing to the great diversity and versatility of the apparently simple building principle of an arthropod cuticular hair. Since the real hairs of mammals are made of keratin and evolved completely differently from the cuticular hairs of arthropods, the correct anatomical term for a cuticular hair-like structure in zoology is seta (pl. setae). However, we use both terms synonymously in this study.

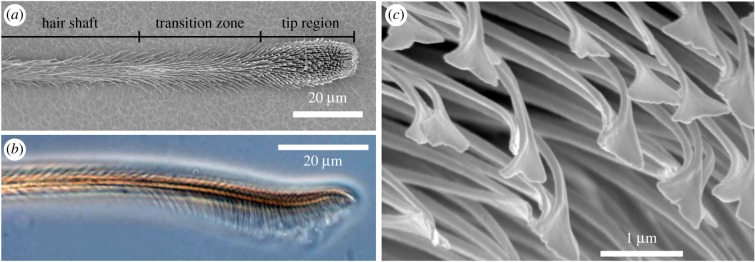

The pretarsal hairy attachment structures of the spider C. salei are called the claw tuft or pretarsal scopula [4,40], which comprises approximately 1000 setae located at the distal end of each leg in between two claws that are used for clamping on rough surfaces. The attachment setae are 200–800 µm long, dependent on the exact location in the claw tuft. The surface of the attachment hairs is covered with thousands of cuticular protuberances, the so-called microtrichs, branching off the shaft of each seta. In the adhesive tip region of the seta, these microtrichs are highly ordered in up to 20 parallel rows and point away from the shaft backbone at an angle of about 80° (figure 1a,b). Here, the microtrichs consist of narrowing stalks that emerge from the shaft backbone and terminate in approximately 1 µm wide and 20 nm thin spatula-shaped plates, which are the contact elements responsible for the formation of intimate contact with the surface of a substrate and the enhancement of adhesion [3,41] (figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Morphology of the distal part of an attachment hair of the spider Cupiennius salei. (a) Scanning electron micrograph, ventral view. The terminology for the different sections corresponds to the presence of differently shaped microtrichs branching off the shaft of the seta. (b) Phase-contrast transmitted light micrograph, lateral view. In the tip region, the elongated microtrichs are oriented approximately perpendicular to the long axis of the seta and form a brush-like structure. (c) Scanning electron micrograph in the tip region. The spatula-shaped terminal elements of the microtrichs are the contact elements responsible for the spider's adhesion. (Online version in colour.)

The exoskeleton of spiders and thus the attachment setae are made of cuticle, a compound material that consists mainly of proteins and reinforcing polymeric chitin fibres [42]. Chitin is a polysaccharide of (1,4) linked 2-deoxy-2-acetamido-β-d-glucose units [43] and arranged in crystalline chains [44]. It is detectable using wide-angle X-ray diffraction by its characteristic fibre diffraction pattern. Among several chitin subtypes, the one found in arthropods is α-chitin, which is identified by two antiparallel polymer chains arranged helicoidally and an orthorhombic unit cell. Previous studies confirmed the presence of α-chitin in the cuticle of the spider C. salei [45–47]. In the exoskeleton of arthropods, chitin molecules are arranged in nanofibrils, each consisting of 18–25 single chitin chains. These nanofibrils are approximately 2–5 nm thick and 300 nm long. They are embedded in a matrix of structural proteins forming chitin-protein fibres with typical diameters of 50–350 nm [48,49].

In order to obtain more information about the distribution of chitin in the spider attachment hairs and to characterize the structures responsible for the remarkable attachment capabilities of the spider, we mapped the information gained by using synchrotron-based scanning nanofocus X-ray diffraction on distal sections of single attachment setae including the adhesive tip. Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) patterns allowed us to specifically map the distribution of chitin in the different structures of the adhesive seta. Additionally, we obtained data about the orientation of the chitin fibrils. The analysis of the small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) signals gave us insights into the distribution and orientation of mesoscopic structures with size of approximately 100 nm. The main advantage of the methods used over light and electron microscopic techniques was that no further chemical or mechanical sample treatment potentially introducing artefacts was necessary, except mounting of the samples on sample holders suitable for the scanning nanofocus X-ray diffraction set-ups.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

Single attachment hairs (setae) were picked from second and third walking legs of specimens of the spider C. salei (Ctenidae) in the middle of the pretarsal claw tuft. The animals were obtained from the breeding stock of the Department of Neurobiology of the University of Vienna, Austria. Most results were gained from hairs of legs separated from the spider not longer than 5 days prior to the experiment and kept in a fridge whenever possible. In this case, the legs were sealed at their autotomy site on the trochanter using a slightly heated mixture of beeswax and colophony. Single hairs were glued free-standing onto the tip of a sharpened glass capillary using two-component polysiloxane (Coltene light body, Coltène/Whaledent AG, Altstätten, Switzerland) prior to exposure. Some other samples were taken from legs frozen at −20°C for one month and mounted on 200 µm thick frames of Si3N4 sample windows (Norcada Inc., Edmonton, Canada; without membrane) 3 days before the experiments.

2.2. Scanning nanofocus X-ray diffraction

The experiments were performed at the nanofocus extension EH III of the beamline ID13 at the European Synchrotron Research Facility ESRF (Grenoble, France) and the Nanofocus Endstation (operated by Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht and Kiel University) of the MiNaXS-beamline P03 [50] of PETRA III at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY (Hamburg, Germany). At the ESRF, an Eiger X 4M detector (Dectris Ltd., Baden-Daetwill, Switzerland) was set up at a distance of 203.5 mm to the sample. The distance between the 400 µm thick cylindrical beamstop downstream from the sample and the detector was bridged by a helium-filled flight-tube. The wavelength of the X-ray beam focused to a size of 150 × 150 nm2 was 0.847 Å. The maximum lateral resolution of the scanning set-up was set to 200 nm, and data were acquired with exposure times of 1 s. At PETRA III, a Pilatus 1M detector (Dectris Ltd., Baden-Daetwill, Switzerland) was placed at a distance to the sample of 184.2 mm. The wavelength of the X-ray beam sized approximately 400 × 400 nm2 was 0.950 Å. Lateral resolution of the scanning set-up was set to 1 µm at exposure times of 35 s per step. The intensity of the X-ray beam on the sample at PETRA III at the time of the experiments was supposed to be 10–20 times lower that at the ESRF. Data were evaluated using the software package FIT2D (A. P. Hammersley, ESRF, Grenoble, France) and the Python library pyFAI (Data analysis unit, ESRF, Grenoble, France). For quantitative analyses of both the signal intensity and orientation, the two-dimensional diffraction data were converted by azimuthal integration into one-dimensional profiles as a function of the scattering vector q. In total, data were recorded from 17 setae from seven legs of seven different animals, and the most representative examples were selected for presentation.

3. Results

3.1. X-ray diffraction patterns

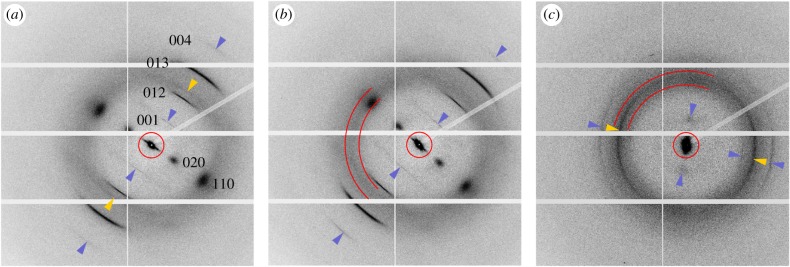

The fibre diffraction pattern of α-chitin and a circular halo with a maximum intensity in the range of q between 13 and 16 nm−1 were the two prominent features of the wide-angle X-ray diffraction signals (figure 2). Except for a slight angular shift of orientation caused by the slight curvature of the sample, the averaged chitin diffraction patterns of the hair shaft and the transition zone located between the shaft and the tip region (figure 1a) were very similar and showed the same reflections (figure 2a,b). There were two broad 020 and 110 reflections on the equator of the diffraction patterns. Of the four reflections off the equator, the 012 and 013 were the most intensive ones. The sharp 001 and 004 meridional reflections were the results of the tilt of the chitin crystals with respect to the X-ray beam. In the tip region, only the 012, 013 and the equatorial 020 reflections could be clearly identified. However, there was an additional, intense and azimuthally widened reflection at q = 14.83 nm−1 in the tip, and a weaker one at q = 13.90 nm−1 in the shaft. No such distinct additional reflection was found in the transition zone (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Averaged X-ray diffraction patterns from different regions of the attachment hair (data from beamtime at the ESRF). (a) Hair shaft, (b) transition zone, (c) tip region. The sharper wide-angle scattering signals correspond to the equatorial 020, and 110, the meridional 001, and 004, and the 012 and 013 reflections of fibrous α-chitin. The circles (a,b,c) indicate the range of small-angle scattering signals. The sector lines (b,c) delimit the range of q-values between 13 and 16 nm−1 that was used for integration of the halo. Dark (blue) arrowheads point to weaker chitin signals as a guide for the eye. Light (yellow) arrowheads (a,c) point to the yet unidentified non-chitin reflections. Note that the longitudinal orientation of the crystalline chitin chains is perpendicular to the equator of the XRD/WAXS signals, and the longitudinal orientation of larger mesoscopic structures is perpendicular to the long axis of the SAXS signals. (Online version in colour.)

The origin of the diffuse halo in between q of approximately 12–20 nm−1 could not be determined with absolute certainty. For further quantitative analysis and intensity mapping, the integration range for the halo was limited from 13 to 16 nm−1. This range clearly excluded the 012 and 013 chitin reflections, however included most of the equatorial 110 chitin reflection and the additional non-chitin signals (figure 2b,c). Consequently, these integration results were addressed to be a mixed signal of yet unidentified amorphous material and chitin. A similar superposition of signals of different origin applied to the chitin 012 and 013 peaks that were superimposed by the boundaries of the halo, and the 110 reflection which widely overlapped with the most intense region of the halo. In the case of the 013 reflection, the peak-to-halo relation was largest, and this is why it was used as an indicator for the presence of chitin further in this study.

Significant differences of the equatorial 020 chitin peak were found in the different regions of the seta. Compared to the shaft and transition zone, the peak from the tip region was broader and shifted to smaller q-values (figure 3). Estimating crystal diameter using the Scherrer equation [51] on the positions and widths of the Lorentz fits of the 020 reflections yielded minimum crystal sizes of 2.59 nm ± 0.02 nm for the tip region, larger values of 2.71 nm ± 0.03 nm for the transition zone and 2.66 nm ± 0.03 nm for the hair shaft, where the uncertainties originated from the Gaussian error distributions of the fits. The position of the equatorial 020 reflection also deviated most from the reference values of purified α-chitin (table 1).

Figure 3.

Peak of the wide-angle 020 diffraction signal of chitin in different functional regions of the attachment seta. The thicker lines are Lorentz peaks fitted to measured data (thinner lines). (Online version in colour.)

Table 1.

Peaks of the diffraction vector q of the α-chitin fibre diffraction pattern of the attachment hairs and reference values.

| reflection peak | 020 (nm−1) | 110 (nm−1) | 001 (nm−1) | 012 (nm−1) | 013 (nm−1) | 004 (nm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shafta | 5.90 ± 0.02 | 13.57 ± 0.01 | 6.23 ± 0.01 | 12.35 ± 0.01 | 18.63 ± 0.01 | 24.52 ± 0.01 |

| tip regionb | 6.39 ± 0.23 | 13.78 ± 0.15 | — | 12.32 ± 0.07 | 18.59 ± 0.04 | 24.52 ± 0.08 |

| lobster tendonc [43] | 6.62 | 13.54 | 6.14 | 12.27 | 18.59 | 24.54 |

| crab tendonc [52] | 6.65 | 13.68 | 12.57 | 18.51 | 24.35 |

aFresh sample (data from beamtime at the ESRF); values from average diffraction pattern based on 1853 single diffraction patterns ± error of the fit (N = 1).

bPreviously frozen sample (data from beamtime at PETRA III); number of diffraction patterns n used for calculation of the mean values ± standard deviations (s.d.): 020: n = 17, 110: n = 38, 012: n = 41, 013: n = 41, 004: n = 22 (N = 1).

cDeproteinized.

No significant differences were found between the different sample preparations and set-ups. The reflection patterns were the same with only slight differences of the chitin q-values (table 1), and the exception that the 001 reflection was not observed in the previously frozen samples examined at the MiNaXS-beamline P03 at PETRA III. In these samples, the additional non-chitin peak in the tip region was found at q = 15.16 nm−1, compared to q = 14.83 nm−1 in the fresh samples examined at the ESRF. With the lower spatial resolution used at PETRA III, the 013 reflections of chitin fibres were detectable up to 1 µm from the very tip of the attachment seta.

The chitin structures suffered severe damage from continuous and long-term exposure to the intense and focused X-rays as indicated by a clear decrease of the wide-angle diffraction signal intensity over time. Half-life of signal intensity measured on data from the ESRF for the 110 reflection was 6.9 s (electronic supplementary material, figure S1a), and 6.5 s for the 020 reflection of the same hair. After 10 s of continuous exposure, the signal-to-noise ratio had already decreased to levels no longer suited for easy and proper analysis. Interestingly, the SAXS intensity slowly rose up to approximately 20 s exposure time and increased quickly to approximately fivefold the initial intensity value at 40 s exposure time of the same spot (electronic supplementary material, figure S1b).

3.2. Mapping microtrich orientation using SAXS

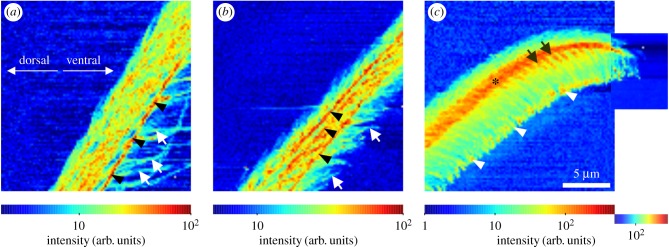

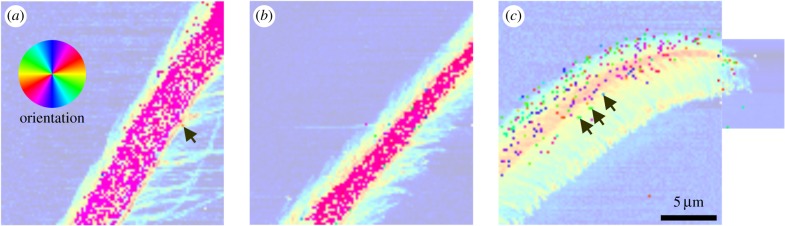

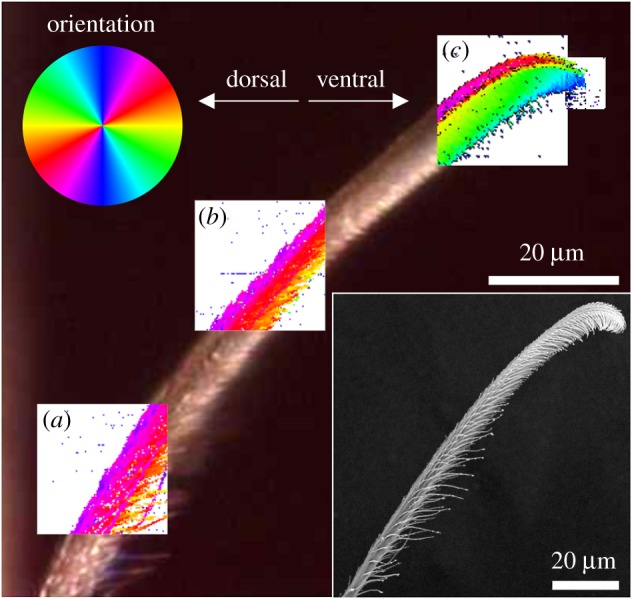

Three areas sized 20 × 20 µm2 and a smaller patch at the very tip were selected in the three different functional regions of the distal part of the attachment hair (figure 4). These areas were scanned with a resolution of 200 nm resulting in 10 201 diffraction patterns each. Orientation of the mesoscopic structures identified by SAXS coincided with the longitudinal orientation of the microtrichs branching off the bulk hair shaft in all examined regions of the seta.

Figure 4.

Maps of orientation of mesoscopic structures (sized ∼100 nm) based on the SAXS signal's main orientation in different regions of the attachment seta. The angle of the mesoscopic structures corresponds to the orientation of the colours of the colour circle. (a) Hair shaft, (b) transition zone, (c) tip region. The background image for the overlaid maps is an optical micrograph of the actual position of the seta in the experimental set-up. The inset shows a scanning electron micrograph of the seta long after the X-ray experiments. In the living spider, a substrate surface to attach to would be oriented vertically on the right side of the images. (Online version in colour.)

In the hair shaft region, fibre orientation determined using the SAXS signals clearly matched the physical orientation of single microtrichs on the ventral side of the seta. Dorsally single microtrichs could not be resolved. However, the orientation of the SAXS signals indicated the orientation of the overlapping microtrich rows that were simultaneously exposed to the X-ray beam at each pixel of the map (figure 4a).

In the transition zone, the number of microtrichs per area increased and made identification of single structures more difficult, especially in the middle of the seta. On the dorsal side, the angular orientation of the microtrichs was approximately 20° off the long axis of the whole seta, and 30° to 40° to the opposite direction on the ventral side (figure 4b).

In the tip region, the SAXS signal orientation clearly differentiated between the dorsal and ventral microtrichs (figure 4c). Dorsally, the microtrichs pointed towards the dorsal side and were shifted to the seta long axis by an angle of approximately 10°. The stalks of the ventral microtrichs were oriented between 70° and 90° towards the ventral aspect of the hair. At the ventral boundary of the SAXS signal, a strip oriented approximately 10° to 20° different from the microtrich stalks likely showed the main orientation of the spatula-shaped adhesive contact elements in the tip region of the microtrichs (figure 4c).

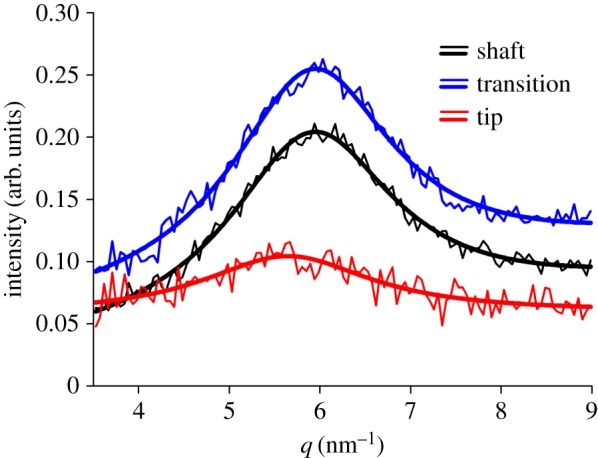

3.3. Mapping of SAXS intensity

The full dimensions of the structures of the setae were best resolved by mapping the intensity distribution of the small-angle scattering signals (figure 5). In the shaft region, single long microtrichs could be resolved best on the ventral side of the hair. On the bulk hair shaft, several separated line-shaped structures with a high intensity most likely corresponded to the branching sites of single long microtrichs. A single line of maximum intensity was located exactly at the boundary surface of the bulk shaft of the seta with air (figures 5a and 6a). In the bulk hair shaft of the transition zone, three lines with increased signal intensity were observed (figure 5b). They coincide with the two boundaries of the longitudinally oriented chitin-rich area of the bulk hair shaft of the transition zone, and the boundary of the bulk hair shaft with air as observed in the WAXS intensity maps (figure 6b).

Figure 5.

Small-angle X-ray scattering intensity maps. (a) Shaft region, (b) transition zone, (c) tip region, as shown in figure 4. In each map, the intensity range was adjusted for the maximum contrast as indicated by the colour bars. The arrows in (a) point to clearly visible single microtrichs, and the arrowheads to a line with increased intensity at the edge of the bulk hair shaft. In the transition zone (b), the arrows indicate single microtrichs. Arrowheads point to several lines with increased intensity oriented along the hair's long axis. In the tip region (c), the most intense scattering signal was measured in a backbone-like structure (asterisk), from which the rows of microtrichs branch off (arrows). Arrowheads point to the intense scattering in the spatula region of the microtrichs. (Online version in colour.)

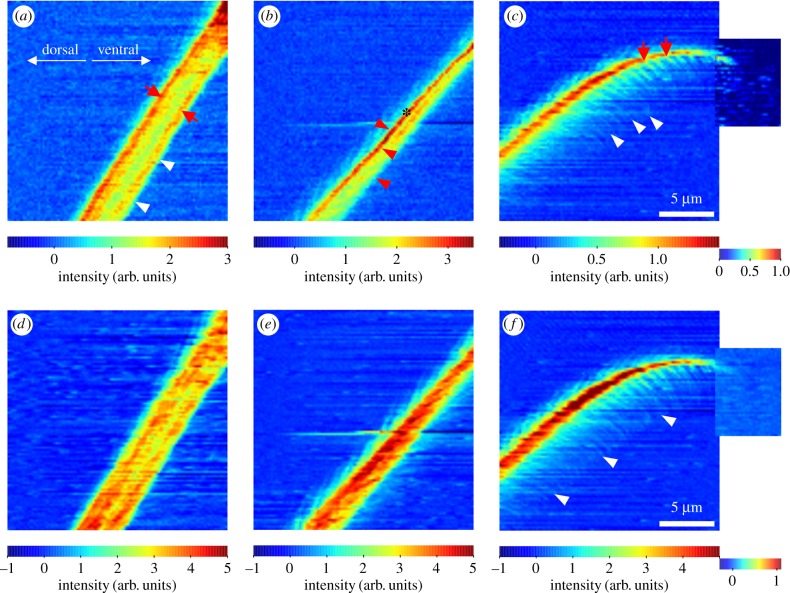

Figure 6.

Wide-angle X-ray diffraction/scattering intensity maps. In each map, the intensity range was adjusted for maximum contrast as indicated by the colour bars. Upper line: Intensity of the 013 chitin reflection. (a) Hair shaft; the arrows point to the walls of the probably hollow shaft, and the arrowheads point to the edge of the seta at the same position as the line of increased small-angle scattering in figure 5a. (b) Transition zone; arrowheads correspond to the positions of the lines of increased small-angle scattering in figure 5b. The asterisk marks the line of the most intense chitin signal. (c) Tip region; arrows indicate rows of microtrichs branching off the backbone. Arrowheads indicate the outreach of the 013 signal following the microtrichs. Lower line: intensity of the WAXS signal integrated between q-values of 13 and 16 nm−1 (halo including parts of the 110 reflection of chitin and the yet unidentified non-chitin signals). (d) Hair shaft, (e) transition zone, (f) tip region. The arrowheads in (f) are at the same position as in figure 5c and illustrate the length of the microtrichs. (Online version in colour.)

Maximum SAXS intensities in the tip region (figure 5c) overlap with the area of the change in orientation of the mesoscopic structures, from along the seta's main axis to perpendicular to it (figure 4c), indicating that it most likely represents the bulk hair shaft and the area of branching of the microtrich rows in the broadest section of the brush-like hair tip structure (compare figure 1a). Interestingly, increased SAXS intensity was also found in the region of the spatula-shaped structures at the tips of the microtrichs and likely indicated strong scattering of the X-ray beam by the thin and flat spatulae (figure 5c).

3.4. Chitin distribution and orientation

The intensity map of the wide-angle 013 chitin reflection of the hair shaft region clearly revealed the dimension of the bulk shaft of the seta with practically no diffraction signal from the microtrichs. The two walls of the bulk shaft of the seta pointed to a tube-shaped arrangement of this section. Interestingly, the diffraction intensity of the dorsal wall was higher than that of the ventral one, indicating higher chitin density and therefore stronger material of the dorsal wall compared with the ventral wall (figure 6a). In the transition zone, there was an approximately 500 nm thick line with high intensity of the 013 reflection located dorsally in the bulk shaft of the seta, too. Additionally, some 013 signal could be located in the region of branching microtrichs dorsal and ventral of the bulk shaft of the seta (figure 6b). In the tip region, the most intense 013 diffraction signal was measured in the core backbone structure narrowing towards the very tip. The signal intensity was clearly increased in the zone of microtrichs branching off the backbone. A slight chitin signal could be detected up to the tips of the microtrichs (figure 6c).

Mapping the intensity of the reflections in the q-range between 13 and 16 nm−1 including the 110 chitin and the yet unidentified non-chitin signals was less selective in terms of identification of specific structures. In the shaft region, the intensity of this mixed signal was more evenly distributed in the bulk material, and maximum intensity areas overlapped with those of the 013 chitin peaks in the wall region. Close to the bulk shaft of the seta, weak signals of the microtrich structures could be observed (figure 6a,d). In the transition zone, the area with the highest intensity of the mixed signal was found in the bulk hair shaft matching the backbone structure with increased SAXS intensity. Signals of branching microtrichs were observed dorsally and ventrally (figures 5b and 6e). In the tip region, the area of high intensity of the mixed wide-angle X-ray diffraction signal was larger than that of the 013 chitin peak. It was centred in the highest intensity region of the SAXS intensity maps and clearly showed the dimension of the bulk material backbone in the brush region of the seta. Branching of microtrich rows and weak signals along the long axis of the microtrichs could be mapped up to the spatula region (figure 6f).

Orientation of the azimuthal 013 chitin reflection was mapped for the data points with sufficient signal intensity. In the hair shaft region and the transition zone, the orientation of the crystalline chitin chains strictly followed the long orientation of the seta. Orientation along microtrichs was only found in single data points close to the bulk hair shaft (figure 7a,b). Orientation mapping in the tip region was difficult, most likely because of the three-dimensional overlap of many different structures and low signal-to-noise ratio. However, quite several single data points in the backbone region showed orientation along the long axis of the seta, and some in the microtrich branching region along the proposed long axis of the microtrichs (figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Orientation maps of the 013 wide-angle X-ray diffraction/scattering reflection showing the orientation of crystalline chitin as indicated by the colour circle. The SAXS intensity maps are plotted in the background. (a) Note the strict orientation of the signal along the long axis of the hair shaft. The arrow points to a single position, where the orientation follows a branching microtrich. (b) Transition zone. (c) Multiply oriented chitin crystals in the tip region. The arrows point to positions, where the orientation appears to match the longitudinal axis of the microtrichs. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

The lattice parameters indicating the physical dimensions of the orthorhombic unit cell were calculated from the positions of the chitin wide-angle reflections and are listed and compared with those of other chitin samples in table 2. The size of the crystalline unit cell, i.e. repeating distance, along the long axis of the polymer determined by parameter c was slightly larger than that of purified chitin and in the range found for chitin of the spider's fang. Parameter a quantifying the distance between two nearest sheets of the same direction in one specific cross-section of the polymer's long axis very well matched the values of deproteinized and purified α-chitin. Parameter b indicates the repeating distance between two chains with the same orientation (each consisting of a pair of antiparallel chains running in the opposite direction along the c axis) in the direction of the hydrogen bonds and showed the largest deviation from the reference values of purified α-chitin. Similar large values were also found in the spider's fang [46]. For the determination of parameter b, the position of the equatorial 020 reflection, which differed strongest from the α-chitin reference value (table 1), was most important. The position and width of the 020 reflection varied in different sections of the seta (figure 3). According to the Scherrer equation, the widened peak in the tip region pointed to smaller crystal sizes. Compared with the 020 peaks of the hair shaft region and the transition zone at q = 5.94 nm−1 it was found shifted by −0.30 nm−1 to the smaller value of q = 5.64 nm−1 in the tip region.

Table 2.

Lattice parameters a, b and c of the orthorhombic unit cell of chitin in the attachment hair, a leg tendon, and the fang of Cupiennius salei, and reference values from purified chitin samples.

Similar changes of reflection peaks were reported for cellulose and explained by an increased influence of crystal surface effects and distortions by surrounding materials, such as hemicelluloses, on the lattice of smaller crystals, leading to an increase of the lattice parameter in the weakest direction [53]. In chitin, only four hydroxyl groups in each repeating unit are responsible for the b-directed hydrogen bonds between the single chains [54]. These hydrogen bonds of the unit cell are most susceptible to interactions with other molecules in the surroundings, such as water and cuticular proteins. Consequently, apart from possible size-effects as in cellulose, the adsorption of water and cuticular proteins to the chitin chains could additionally explain the shift of the 020 peak and the deviation of b from purified chitin as discussed previously [47].

Minimum chitin crystal sizes of the different regions of the attachment seta were 2.59 nm ± 0.02 nm (error of the fit) in the tip, 2.71 nm ± 0.03 nm in the transition zone and 2.66 nm ± 0.03 nm in the hair shaft (calculated from position and width of the reflection peaks using the Scherrer equation). These values were well within the range of the diameters between 2.5 nm and 3.0 nm found in the literature for the molecular chitin chains that are typically bundled to nanofibrils and wrapped by proteins [44,49].

Functionally different crystal sizes in the different sections of the attachment seta can be explained as follows. Smaller crystals in the tip region likely result in increased flexibility promoting contact formation with a surface and eventually adhesion. Similar mechanical effects, based on the transition from stiff to soft material in the tip, were previously reported for the attachment setae of coccinellid beetles [31]. When compared with the shaft region of the spider seta, which is mechanically reinforced against buckling by its tube-shaped hollow structure (figure 6a), the mechanically more stable larger cell size in the transition zone of the spider hair can be explained as adaptation to a proposed stress concentration in the narrowed backbone (figure 6b) upon contact of the seta with the substrate surface.

The origin of the reflection at q = 13.90 nm−1 in the shaft region (figure 2a) and the azimuthally widened reflection at q = 14.83 nm−1 in the tip region (figure 2c) finally remained unidentified. However, these reflections were likely caused by the protein matrix surrounding the chitin fibrils. Valverde Serrano et al. [47] found a similar peak at q = 13.89 nm−1 in the cuticle of dry intact leg tendons of C. salei, which disappeared upon deproteinization, strongly pointing to its origin in the proteinaceous β-sheet motif. The high intensity of the proposed protein reflection in the tip region of the attachment seta can be explained by an increased amount of structural proteins making up the shapes of the many and highly ordered microtrichs.

The strict orientation of the chitin fibrils in parallel along the longitudinal axis of the attachment seta is remarkable (figure 7), especially in comparison with the arrangement of chitin fibres in other body parts, such as the leg cuticle, where the chitin fibrils are mostly arranged in a plywood manner of helicoidally rotating layers in parallel with the surface [42,46,55]. Alignment of chitinous fibres perpendicular to the surface was shown for the soft adhesive pads of grasshoppers and locusts [56,57]. It was attributed to enhanced flexibility of the material under compression load, necessary for contact formation especially with uneven surfaces. For an animal, sitting on a vertical surface or upside down, the perpendicular orientation of the fibres can also be interpreted as an adaptation to the tensile forces that arise upon attachment. Most likely, the same is true for the fibrils in the spider's attachment hair, and the longitudinal orientation of the fibres reinforces the structure in the direction of the tensile forces that act when the animal sits on a vertical surface, which is the preferred resting position of C. salei.

The intensity of the identified chitin reflections in figure 7a–c corresponds to the density of chitin in the cuticle material. The chitin fibres reinforcing the cuticle can be interpreted as specifically distributed to maintain and reinforce the mechanical stability of the attachment setae. The larger chitin density in the dorsal wall of the hair shaft likely reinforces it against buckling, when the seta is pushed onto a surface. The less stiff ventral wall allows sufficient structural compliance, when the seta is pulled off. A similar mechanical behaviour can be proposed for the asymmetrically reinforced transition zone that by its shape is supposed to be more flexible. In the tip region, the backbone serves as the structure to hold several hundred microtrichs in place and showed the highest chitin content. In the region of the microtrichs, the wide-angle diffraction signal of chitin was weak, but was however, present up to the tip indicating that the stalk and likely also the spatula-shaped adhesive contact elements were chitin-reinforced. To sum up, it seems very likely that the strains and stresses that arise from the forces that act on the adhesive tip during attachment, adhesion in contact and detachment at every step of the spider, are most evenly distributed by the arrangement pattern of the reinforcing chitin fibres to avoid material failure.

Using scanning nanofocus X-ray diffraction on a microscopic level allowed us to find yet unknown structures of the spider attachment hairs. Unique to X-ray diffraction was the possibility to specifically identify and localize the chitin fibres and their orientation within the cuticle of the attachment hair. In future experiments, it would be interesting to attach and detach attachment hairs to a surface in situ in the scanning nanofocus X-ray diffraction set-up, in order to quantify changes in fibre orientation in the adhesive tip and other regions of the seta. This will allow for further extraction of structure-function relationships for further improvement of novel biologically inspired artificial structured adhesives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities at beamline ID13. Parts of this research were carried out at MiNaXS-beamline P03 of PETRA III at DESY, a member of the Helmholtz Association (H.G.F.). We thank Emanuela Di Cola for assistance during a previous beamtime at the ESRF that led to the experimental set-up of the present study, and Prof. Dr Friedrich G. Barth and Wolfgang Kallina from the Department of Neurobiology of the University of Vienna, Austria, for supply with living spiders.

Data accessibility

All relevant data are included in the text, figures, tables, and electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

C.F.S., M.M., and S.N.G. conceived of the study. C.F.S., A.G., M.B., M.R. and C.K. designed the experiments. C.F.S. and S.F. prepared the samples. C.F.S., S.F., A.G., I.K., M.B., M.R., H.S., C.K. and M.M. carried out the beamtime work. S.F., C.F.S., I.K., A.G. and M.B. evaluated the raw data. C.F.S., S.F. and M.M. interpreted the data. C.F.S. drafted the manuscript. S.F. contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. S.F., M.M. and S.N.G. commented on the draft of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The allocation of beamtime and travel grants from ESRF to C.F.S., M.M., S.F., I.K., A.G. and H.S. and Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht to C.F.S. and A.G. are greatly acknowledged. The work of I.K. and A.G. was funded within the Helmholtz Virtual Institute ‘New X-ray analytic methods in materials science (VI-NXMM)’ of the Helmholtz Association (H.G.F.).

References

- 1.Homann H. 1957. Haften Spinnen an einer Wasserhaut? Naturwissenschaften 44, 318–319. ( 10.1007/BF00630926) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roscoe DT, Walker G. 1991. The adhesion of spiders to smooth surfaces. Bull. Brit. Arachnol. Soc. 9, 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederegger S, Gorb SN. 2006. Friction and adhesion in the tarsal and metatarsal scopulae of spiders. J. Comp. Physiol. A 192, 1223–1232. ( 10.1007/s00359-006-0157-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolff JO, Gorb SN. 2013. Radial arrangement of Janus-like setae permits friction control in spiders. Sci. Rep. 3, 1101 ( 10.1038/srep01101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorb SN. 1998. The design of the fly adhesive pad: distal tenent setae are adapted to the delivery of an adhesive secretion. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 747–752. ( 10.1098/rspb.1998.0356) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geiselhardt SF, Lamm S, Gack C, Peschke K. 2010. Interaction of liquid epicuticular hydrocarbons and tarsal adhesive secretion in Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Comp. Physiol. A 196, 369–378. ( 10.1007/s00359-010-0522-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dirks J-H, Federle W. 2011. Fluid-based adhesion in insects – principles and challenges. Soft Matter 7, 11047 ( 10.1039/c1sm06269g) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovalev AE, Filippov AE, Gorb SN. 2013. Insect wet steps: loss of fluid from insect feet adhering to a substrate. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 201206939 ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.0639) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gernay S, Federle W, Lambert P, Gilet T. 2018. Elasto-capillarity in insect fibrillar adhesion. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160371 ( 10.1098/rsif.2016.0371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maderson PFA. 1964. Keratinized epidermal derivatives as an aid to climbing in gekkonid lizards. Nature 203, 780–781. ( 10.1038/203780a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Autumn K, Liang YA, Hsieh ST, Zesch W, Chan WP, Kenny TW, Fearing R, Full RJ. 2000. Adhesive force of a single gecko foot-hair. Nature 405, 681–685. ( 10.1038/35015073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Autumn K, et al. 2002. Evidence for van der Waals adhesion in gecko setae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12 252–12 256. ( 10.1073/pnas.192252799) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber G, Gorb SN, Spolenak R, Arzt E. 2005. Resolving the nanoscale adhesion of individual gecko spatulae by atomic force microscopy. Biol. Lett. 1, 2–4. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0254) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzo NW, Gardner KH, Walls DJ, Keiper-Hrynko NM, Ganzke TS, Hallahan DL. 2006. Characterization of the structure and composition of gecko adhesive setae. J. R. Soc. Interface 3, 441–451. ( 10.1098/rsif.2005.0097) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber G, Orso S, Spolenak R, Wegst UGK, Enders S, Gorb SN, Arzt E. 2008. Mechanical properties of a single gecko seta. Int. J. Mater. Res. 99, 1113–1118. ( 10.3139/146.101750) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alibardi L. 2018. Review: mapping proteins localized in adhesive setae of the tokay gecko and their possible influence on the mechanism of adhesion. Protoplasma 255, 1785–1797. ( 10.1007/s00709-018-1270-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kesel AB, Martin A, Seidl T. 2003. Adhesion measurements on the attachment devices of the jumping spider Evarcha arcuata. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 2733–2738. ( 10.1242/jeb.00478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kesel AB, Martin A, Seidl T. 2004. Getting a grip on spider attachment: an AFM approach to microstructure adhesion in arthropods. Smart Mater. Struct. 13, 512–518. ( 10.1088/0964-1726/13/3/009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geim AK, Dubonos SV, Grigorieva KS, Novoselov KS, Zhukov AA, Shapoval SY. 2003. Microfabricated adhesive mimicking gecko foot hair. Nat. Mater. 2, 461–463. ( 10.1038/nmat917) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sitti M, Fearing RS. 2003. Synthetic gecko foot-hair micro/nano-structures as dry adhesives. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 18, 1055–1073. ( 10.1163/156856103322113788) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yurdumakan B, Raravikar NR, Ajayan PM, Dhinojwala A. 2005. Synthetic gecko foot-hairs from multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3799–3801. ( 10.1039/B506047H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge L, Sethi S, Ci L, Ajayan PM, Dhinojwala A. 2007. Carbon nanotube-based synthetic gecko tapes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10 792–10 795. ( 10.1073/pnas.0703505104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee H, Lee BP, Messersmith PB. 2007. A reversible wet/dry adhesive inspired by mussels and geckos. Nature 448, 338–341. ( 10.1038/nature05968) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahdavi A, et al. 2008. A biodegradable and biocompatible gecko-inspired tissue adhesive. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2307–2312. ( 10.1073/pnas.0712117105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qu L, Dai L, Stone M, Xia Z, Wang ZL. 2008. Carbon nanotube arrays with strong shear binding-on and easy normal lift-off. Science 322, 238–242. ( 10.1126/science.1159503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boesel LF, Greiner C, Arzt E, del Campo A. 2010. Gecko-inspired surfaces: a path to strong and reversible dry adhesives. Adv. Mater. 22, 2125–2137. ( 10.1002/adma.200903200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen B, Goldberg Oppenheimer P, Shean TAV, Wirth CT, Hofmann S, Robertson J. 2012. Adhesive properties of gecko-inspired mimetic via micropatterned carbon nanotube forests. J. Phys. Chem. 116, 20 047–20 053. ( 10.1021/jp304650s) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaber CF, Heinlein T, Keeley G, Schneider JJ, Gorb SN. 2015. Tribological properties of vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays. Carbon 94, 396–404. ( 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.07.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frost SJ, Mawad D, Higgins MJ, Ruprai H, Kuchel R, Tilley RD, Myers S, Hook JM, Lauto A. 2016. Gecko-inspired chitosan adhesive for tissue repair. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e280 ( 10.1038/am.2016.73) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peisker H, Michels J, Gorb SN. 2013. Evidence for a material gradient in the adhesive tarsal setae of the ladybird beetle Coccinella septempunctata. Nat. Commun. 4, 1661 ( 10.1038/ncomms2576) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barth FG. 2002. A spider's world: senses and behavior. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConney ME, Schaber CF, Julian MD, Barth FG, Tsukruk VV. 2007. Viscoelastic nanoscale properties of cuticle contribute to the high-pass properties of spider vibration receptor (Cupiennius salei Keys). J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 1135–1143. ( 10.1098/rsif.2007.1000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fratzl P, Barth FG. 2009. Biomaterial systems for mechanosensing and actuation. Nature 462, 442–448. ( 10.1038/nature08603) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Politi Y, Pippel E, Licuco-Massouh ACJ, Bertinetti L, Blumtritt H, Barth FG, Fratzl P. 2017. Nano-channels in the spider fang for the transport of Zn ions to cross-link His-rich proteins pre-deposited in the cuticle matrix. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 46, 30–38. ( 10.1016/j.asd.2016.06.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohlfart E, Wolff JO, Arzt E, Gorb SN. 2014. The whole is more than the sum of all its parts: collective effect of spider attachment organs. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 222–224. ( 10.1242/jeb.093468) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albert JT, Friedrich OC, Dechant H-E, Barth FG. 2001. Arthropod touch reception: spider hair sensilla as rapid touch detectors. J. Comp. Physiol. A 187, 303–312. ( 10.1007/s003590100202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McConney ME, Schaber CF, Julian MD, Eberhardt WC, Humphrey JAC, Barth FG, Tsukrukl VV. 2009. Surface force spectroscopic point load measurements and viscoelastic modelling of the micromechanical properties of air flow sensitive hairs of a spider (Cupiennius salei). J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 681–694. ( 10.1098/rsif.2008.0463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaber CF, Barth FG. 2015. Spider joint hair sensilla: adaptation to proprioreceptive stimulation. J. Comp. Physiol. A 201, 235–248. ( 10.1007/s00359-014-0965-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barth FG. 2016. A spider's sense of touch: what to do with myriads of tactile hairs? In The ecology of animal senses (eds von der Emde G, Warrant E), pp. 27–58. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorb SN. 2001. Attachment devices of insect cuticle. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolff JO, Gorb SN. 2012. Surface roughness effects on attachment ability of the spider Philodromus dispar (Araneae, Philodromidae). J. Exp. Biol. 215, 179–184. ( 10.1242/jeb.061507) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barth FG. 1973. Microfiber reinforcement of an arthropod cuticle. Z. Zellforsch. 144, 409–433. ( 10.1007/BF00307585) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minke R, Blackwell J. 1978. The structure of α-chitin. J. Mol. Biol. 120, 167–181. ( 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90063-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neville AC, Parry DAS, Woodhead-Galloway J. 1976. The chitin crystallite in arthropod cuticle . J. Cell. Sci. 21, 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Politi Y, Priewasser M, Pippel E, Zaslansky P, Hartmann J, Siegel S, Li C, Barth FG, Fratzl P. 2012. A spider's fang: how to design an injection needle using chitin-based composite materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 2519–2528. ( 10.1002/adfm.201200063) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erko M, Hartmann MA, Zlotnikov I, Valverde Serrano C, Fratzl P, Politi Y. 2013. Structural and mechanical properties of the arthropod cuticle: comparison between the fang of the spider Cupiennius salei and the carapace of American lobster Homarus americanus. J. Struct. Biol. 183, 172–179. ( 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.06.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valverde Serrano C, Leemreize H, Bar-On B, Barth FG, Fratzl P, Zolotoyabko E, Politi Y. 2016. Ordering of protein and water molecules at their interfaces with chitin nano-crystal. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 124–131. ( 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.12.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vincent JFV, Wegst UGK. 2004. Design and mechanical properties of insect cuticle. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 33, 187–199. ( 10.1016/j.asd.2004.05.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raabe D, Al-Sawalmih A, Yi SB, Fabritius H. 2007. Preferred crystallographic texture of α-chitin as a microscopic and macroscopic design principle of the exoskeleton of the lobster Homarus americanus. Acta Biomater. 3, 882–895. ( 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krywka C, Neubauer H, Priebe M, Salditt T, Keckes J, Buffet A, Roth SV, Doehrmann R, Mueller M. 2012. A two-dimensional waveguide beam for X-ray nanodiffraction. J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 85–92. ( 10.1107/S0021889811049132) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azaroff LV. 1968. Elements of X-ray crystallography. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikorski P, Hori R, Wada M. 2009. Revisit of a-chitin crystal structure using high resolution X-ray diffraction data. Biomacromolecules 10, 1100–1105. ( 10.1021/bm801251e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Müller M, Murphy B, Burghammer M, Riekel C, Pantos E, Gunneweg J. 2007. Ageing of native cellulose fibres under archaeological conditions: textiles from the Dead Sea region studied using synchrotron X-ray microdiffraction. Appl. Phys. A 89, 877–881. ( 10.1007/s00339-007-4219-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friák M, Fabritius H-O, Nikolov S, Petrov M, Lymperakis L, Sachs C, Elstnerová P, Neugebauer J, Raabe D. 2013. Multi-scale modelling of a biological material: the arthropod exoskeleton In Materials design inspired by nature: function through inner architecture (eds Fratzl P, Dunlop JWC, Weinkamer R), pp. 197–218. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hößl B, Böhm HJ, Schaber CF, Rammerstorfer FG, Barth FG. 2009. Finite element modeling of arachnid slit sensilla: II. Actual lyriform organs and the face deformations of the individual slits. J. Comp. Physiol. A 195, 881–894. ( 10.1007/s00359-009-0467-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gorb S, Jiao Y, Scherge M. 2000. Ultrastructural architecture and mechanical properties of attachment pads in Tettigonia viridissima (Orthoptera Tettigoniidae). J. Comp. Physiol. A 186, 821–831. ( 10.1007/s003590000135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez Goodwyn P, Peressadko A, Schwarz H, Kastner V, Gorb S. 2006. Material structure, stiffness, and adhesion: why attachment pads of the grasshopper (Tettigonia viridissima) adhere more strongly than those of the locust (Locusta migratoria) (Insecta: Orthoptera). J. Comp. Physiol. A 192, 1233–1243. ( 10.1007/s00359-006-0156-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the text, figures, tables, and electronic supplementary material.