Abstract

Molecular imaging of prostate cancer is in a dynamic phase of development. Currently approved techniques are limited and researchers have been working on novel agents to improve accuracy in targeting and detecting prostate tumors. In addition, the complexity of various prostate cancer states also contributes to the challenges in evaluating suitable radiotracer candidates. We have highlighted nuclear medicine tracers that focus on mechanisms involved in bone metastasis, prostate cancer cell membrane synthesis, amino acid analogs, androgen analogs, and the prostate specific membrane antigen. Encouraging results with many of these innovative radiotracer compounds will not only advance diagnostic capabilities for prostate cancer but open opportunities for theranostic applications to treat this worldwide malignancy.

Keywords: 18F NaF, 11C acetate, 11C/18F choline, 18F DHT, 18F FACBC, 18F DCFBC, 68Ga PSMA

Introduction

With over one million men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer and over 300,000 deaths per year worldwide in 2012 [1], there is great interest in better imaging tools for detecting prostate cancer both to aid in patient management and also to improve understanding of the disease. As a biomarker, imaging is a non-invasive, whole body method with immense potential to provide insight regarding tumor burden, assess response to therapeutic intervention, and characterize disease activity. Such knowledge could assist the development of personalized treatment strategies directed at yielding maximum benefit while minimizing adverse side effects. Prostate cancer management, in particular, can be greatly influenced by imaging. Evidence of distant metastases in a patient with presumed localized primary cancer completely changes management.

Current imaging methods are limited. The conventional bone scan is a projection image based on a single photon emitting radionuclide and 30-year-old technology. Moreover, it is both insensitive for early metastases, non-specific with regard to other coexisting benign bone disorders and is slow to respond when successful therapies are applied. Computed tomography, the other mainstay of conventional imaging, is insensitive for small nodal metastases and does not adequately depict bone disease. MRI has proven useful in localizing prostate cancer when combined with image-guided biopsy although it has a significant false negative rate. Its use is growing in monitoring metastatic disease but MRI is not yet routine for this. Thus, there are large opportunities for sensitive and specific imaging methods, especially those based on positron emission tomography (PET) technology.

It should be noted that the imaging of prostate cancer is made complicated by the complexity of the disease itself. At initial diagnosis, prostate cancers demonstrate a wide range of biologic activity, the majority of which are low grade and not clinically significant. Thus, it is not sufficient to simply visualize a cancer but also differentiate biologically aggressive types warranting life-altering therapies. When a patient recurs after definitive therapy (surgery or radiation), prostate specific antigen (PSA) starts to rise and in the absence of a known source, this is known as a biochemical recurrence (BCR). Identifying significant recurrences through imaging would be valuable. Finally, in the metastatic state, imaging must be sensitive to both nodal and bony disease, since these represent the most common sites of advanced disease. Nodal involvement may be minimal and bone disease tends to remain positive on bone scan even after the disease is suppressed with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Isolating sites of escape from androgen control, the castration resistant phenotype of prostate cancer, is also an important objective for imaging. Researchers have been studying many novel agents in hopes of reaching some of these goals. Here, we review the current state-of-the-art in PET imaging of prostate cancer.

Sodium Fluoride PET/CT (NaF)

Currently, the workhorse tracer for PET nuclear medicine, 18F FDG (FDG), has unreliable specificity for prostate cancer. Another veteran agent, 18F NaF (NaF) recently became available again for use as a PET tracer. Confined to evaluating only bone metastases, it has better sensitivity compared with traditional bone scintigraphy. However, NaF scans suffer from the same lack of specificity. Nonetheless, the sensitivity of NaF PET can be valuable. Results of the National Oncologic PET Registry (NOPR) revealed that NaF bone scans impacted management and replaced intended use of other advanced imaging in approximately 50 % of the 3531 prostate cancer patients recorded [2]. This included patients who were upstaged from M0 to M1 by NaF. In a group of 2217 mixed cancer patients, when NaF was used to monitor response to therapy, there was a 40 % change in treatment plan [3].

Combining 18F NaF and 18F FDG to improve detection of osseous metastases has been considered. Sampath et al. [4] studied 75 mixed cancer patients (39 with prostate cancer) who underwent combined 18F NaF and 18F FDG PET/CT and a separate diagnostic CT and found the combined PET scan was better at detecting bone metastasis than CT alone with a sensitivity of 97 % compared to 67 % for CT. Specificities were comparable at 86 % for PET and 78 % for CT. A small trial of six prostate cancer patients with castrate resistant bone metastasis evaluated combined NaF and FDG activity and observed some correlations in uptake and spatially dislocated lesion foci [5]. However, given the overall low sensitivity of FDG PET for prostate cancer metastases, the incremental value of adding this second PET scan (with added expense and radiation) is not justified at this time.

The benefit of NaF over traditional 99mTc bone scan (TcBS) for routine use has been questioned. Its higher sensitivity means that more lesions are detected but this added information often does not alter treatment. Greater interest has centered on its ability to measure disease activity in response to treatment. Etchebehere et al. [6••] recently conducted a study of 42 castration resistant prostate cancer patients undergoing 223Ra therapy. They found that quantitative tumor burden indices (total lesion uptake and volume) on baseline NaF scan were highly correlated and both parameters were significant independent predictors of overall survival. Visual analysis alone was not correlated with overall or progression-free survival. The average standardized uptake value (SUV) was, however, a significant risk predictor for skeletal-related events in these patients. This study concluded that NaF is an instrumental tool to assist in decisions regarding therapy with 223Ra. In a smaller study, Yu et al. [7] evaluated NaF in castration resistant patients undergoing dasatinib treatment and noted that SUV changed as a result of therapy, but only 12 patients were studied. Correlations with progression-free survival were borderline in significance.

Evaluating NaF against other tracers, Poulsen et al. [8] studied detection of spine metastasis with NaF, 18F choline (FCH) and TcBS and found NaF superior in sensitivity to FCH (93 vs 85 %) but conversely, FCH superior to NaF in specificity (81 vs 91 %). Both NaF and FCH were better than TcBS in hormone naïve patients.

Thus, NaF PET is most useful in high-risk patients to confidently detect or eliminate bone disease and potentially monitor the effects of therapy on bone metastases.

11C Acetate

11C acetate is a first generation PET tracer exploiting the upregulation of fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer. Acetate is taken up by cells, converted into acetyl-CoA and then oxidized in the mitochondria by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for energy production or, transformed into fatty acids and integrated into the cell membrane. Prostate tumor cells have an overabundance of fatty acid synthase enzyme, predominantly favoring the conversion of acetate to fatty acids used to produce phosphatidylcholine found in cell membranes. Thus, fatty acid synthesis promotes survival and growth of the cancer [9]. Increased fatty acid synthase activity in cell nuclei has been shown to correlate with aggressive prostate tumors [10].

While 11C acetate has shown some promise in detecting advanced prostate cancer, it has not proven helpful in evaluating localized disease. Mena et al. [11] studied 39 patients with localized disease and found uptake in tumor was higher than normal prostate tissue, but similar to benign prostatic hyperplasia. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies [12], 11C acetate had a sensitivity of 75 % and specificity of 76 % for detecting primary tumor. For this reason, it is not likely to be used as an independent imaging agent for primary cancer; however, it could be beneficial for monitoring recurrence after focal therapy when anatomical distortions from intervention may be difficult to assess with conventional imaging. For intermediate and high-risk patients (tumor grade T2b/c or T3, Gleason score >7 or PSA >10), Haseebuddin et al. [13] found 11C acetate to be helpful in pelvic nodal staging and treatment planning prior to prostatectomy. In biochemical recurrence, the meta-analysis from Mohsen et al. [12] found 11C acetate sensitivity was low (64 %) while specificity was good (93 %). Recently, Leisser et al. [14] retrospectively studied 11C acetate in 123 prostate cancer patients with suspected biochemical relapse. 11C acetate identified recurrence in 82 patients and SUV correlated with initial Gleason score. Higher tumor uptake ratios in PET positive patients were associated with higher PSA velocities, but no correlation was seen with SUV. Another study of 11C acetate in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer was done by Dusing et al. [15]. They retrospectively looked at 120 patients after definitive therapy and found PSA values greater than 1.24 ng/mL or PSA velocity greater than 1.32 ng/mL/year demonstrated a higher percentage of positive findings on PET with a sensitivity of 86.6 % and specificity of 65.8 % for elevated PSA levels and sensitivity of 74 % and specificity of 75 % for PSA velocity. Thus, 11C acetate, as a marker for fatty acid synthase overexpression, could be a useful prognostic indicator for tumor aggressiveness in recurrent disease. However, the performance of 11C acetate in biochemical recurrence is only fair and may be supplanted by other, newer methods. In addition, the half-life of 11C is short at 20 min, limiting its availability to large centers with an on-site cyclotron.

11C/18F Choline

11C/18F choline are two first generation agents tied to the increased cell membrane synthesis of prostate cancer cells. Choline kinase is overexpressed in prostate cancer and the cells use choline to synthesize phosphatidylcholine. Physiologic uptake of the radiotracer is noted in the salivary glands, liver, adrenals, gastrointestinal tract, and urinary tract. Similar to 11C acetate, distinguishing tumor uptake from benign prostatic hyperplasia is usually not possible with 11C/18F choline. Thus, these agents have a limited role in primary disease. Although in the following discussion we lump 11C/18F choline together, there are chemical differences. 11C choline is excreted through the pancreas with little urinary tract activity but a short 20 min half-life. 18F Choline demonstrates more renal excretion and urinary tract activity, but the longer half-life of 110 min makes it more practical.

11C/18F choline are mainly used to detect disease in biochemically recurrent (BCR) patients. Umbehr et al. [16] demonstrated a high sensitivity of 85 % and specificity of 88 % in a meta-analysis of patients with biochemical recurrence. Evangelista et al. [17] performed another meta-analysis with 1555 BCR patients and found the sensitivity and specificity of 86 and 93 % respectively for all sites (prostate fossa, lymph nodes and bone.) Detecting recurrent disease in the prostatectomy fossa had a lower sensitivity of 75 % and specificity of 82 %. Identifying metastatic disease in lymph nodes revealed a sensitivity of 100 % and specificity of 82 %. These results are clearly very promising. However, when Beheshti et al. [18•] prospectively evaluated FCH in 250 patients with bio-chemical relapse, disease was correctly identified in only 74 % of patients. Positive PET findings were significantly predicted by PSA level and administration of ADT. The FDA approved the use of 11C choline for evaluating BCR in September 2012. However, Castellucci et al. [19] studied 11C choline in early BCR after radical prostatectomy (RP) in 605 patients and only detected disease in 28 %. PSA and PSA doubling time were significant predictors for a positive PET with a PSA level of 1.05 ng/mL and doubling time of 5.95 months determined to be critical values for positive PET studies. It is clear that the mix of patients in a series defines the outcomes necessitating multi-institutional studies with fixed entry criteria. False positives are also a problem. For instance, Suardi et al. [21] demonstrated a 20 % false positive rate for lymph nodes in the preoperative setting with FCH.

An interesting phenomenon observed with choline PET is that hormonal therapy may cause bone marrow activation throughout the skeleton causing widespread heterogeneous tracer uptake which may obscure bone metastasis. Despite this, most studies show that choline PET can detect malignant bone disease. Wondergem et al. [20] found choline PET to have better specificity than NaF for bone metastases. On a lesion-based analysis, sensitivity was 84 % and specificity was 97.7 %. Patient-based analysis was similar with sensitivity of 85.2 % and specificity of 96.5 %. Piccardo et al. [21] evaluated 11C choline PET/MR, 11C choline PET/CT, NaF, multiparametric MR, and contrast enhanced CT in 21 patients with suspected prostate cancer recurrence after external beam radiation therapy. 11C choline PET/MR, 11C choline PET/CT, and multiparametric MR were comparable in detection rates at 86, 76, and 81 %, respectively. NaF had the highest sensitivity for bone metastases.

Another way to assess the influence of a radiotracer is to note its effect on patient management or survival. Ceci et al. [22] retrospectively looked at the impact of 11C choline imaging in 150 patients with recurrent prostate cancer. An overall change in therapy because of 11C choline PET occurred in almost 47 % of patients. They also noted that PSA level, doubling time, and ADT were significant predictors for positive scans. 11C choline PET also may have prognostic value. Giovacchini et al. [23] retrospectively looked at 11C choline in 195 radical prostatectomy (RP) patients who developed BCR during ADT and evaluated how it related to their survival. PET was positive in 112 patients. PSA, pathologic stage, and PSA doubling time were worse in patients with positive 11C choline. Skeletal uptake was associated with shorter survival. Patients with positive 11C choline PET/CT scans had median survival of 4.1 years compared to 7.9 years in patients with negative scans. 11C choline PET/CT was fairly accurate in predicting prostate cancer specific survival in this subset of patients.

Thus, 11C/18F choline has been used to detect recurrences in BCR. It has a good sensitivity and specificity for disease. Unfortunately, there is a 20 % false positive rate in nodes which poses a challenge. 11C choline benefits from the relative absence of renal excretion and prior FDA approval whereas 18F choline benefits from a longer half-life but more renal excretion obscuring the pelvis. The primary role of these agents is in BCR where it is limited in detecting cancer in the prostatic fossa but is most useful for detecting nodal and bony disease.

Amino Acid Analogs

A number of amino acid analogs have been proposed as imaging agents for prostate cancer. The most notable of these is 18F FACBC, a leucine analog. Prostate cancers upregulate certain amino acid transporters and this analog is taken up in cancer cells. In primary disease, 18F FACBC shares the problem of non-specificity of uptake that is seen with other first generation agents [24]. For BCR and advanced disease, it appears to perform comparably to 11C acetate and the cholines, although recently, Nanni et al. [25] reported in a small study of 28 patients that 18F FACBC outperformed 11C choline. In general, 18F FACBC has higher sensitivity but lower specificity. For instance, in a trial of 93 patients, Schuster et al. [26] demonstrated a 90 % sensitivity but only a 40 % specificity indicating many false positives. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 251 patients showed a pooled sensitivity of 87 % with a pooled specificity of 66 % [27]. Thus, 18F FACBC appears to be a highly sensitive technique for detecting recurrent disease but suffers from a relatively high false positive rate. Since this could result in false upstaging of disease, the clinical utility of this agent needs to be considered in the context of newer PET agents.

Dihydrotestosterone Analogs (18F DHT)

Prostate cancer is driven by the androgen receptor (AR) so it makes sense that AR-targeted imaging might be useful in depicting cancer. This is especially true in advanced “androgen independent” cancers where high binding may suggest the need for second generation anti-androgen therapies. The PET agent 18 F fluoro-5a-dihydrotestoterone (FDHT) binds to the androgen receptor with high affinity thus demonstrating the location of prostate cancer cells with high expression of wild-type AR. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a derivative of testosterone, is the natural ligand for the androgen receptor. When bound to the androgen receptor, DHT causes normal and malignant prostate cells to proliferate. In theory, the FDHT scan would be most useful in identifying cells with high AR expression. However, mutations in the AR are known to occur but have unknown impact on DHT binding. Beattie et al. [28] demonstrated the potential of FDHT to estimate androgen receptor expression changes in prostate cancer patients during treatment with second generation antiandrogens. Comparing FDHT with FDG, Larson et al. [29] found FDG detected 57/59 lesions and FDHT found 46/59 lesions, establishing the feasibility of FDHT to recognize disease. Further studies in 38 castration resistant patients by Vargas et al. [30] revealed that patients with higher FDHT uptake in bone lesions were more likely to have a shorter survival time. The usefulness of DHT imaging is still uncertain. A novel antiandrogen clinical trial conducted by Rathkopf et al. [31] utilized FDHT imaging to measure effective targeting of the drug, ARN-509, to the androgen receptor. Recent work has been done [32] to construct radiotracers specific to mutated androgen receptors which are exclusive to prostate cancer. To date, only a limited number of sites have produced FDHT and its major role appears limited to acting as a pharmacodynamics marker in clinical trials of antiandrogen therapy.

Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)-Targeted Agents

Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is overexpressed on prostate cancers, especially those with more aggressive histologic features. PSMA is a transmembrane receptor. The function of its external domain is enzymatic including folate hydrolase and NAALDase enzymes while the function of the internal domain is uncertain. PSMA itself does not have any obvious function in prostate cancer cells as its absence or inhibition does not prevent growth. Nonetheless, its overabundance in prostate cancer makes it a target for imaging and therapy agents.

The first generation of PSMA-targeted molecules was antibodies. 111In-capromab pendetide was FDA approved in the 1990s but did not have much impact because it targeted the internal domain of PSMA. The antibody, J591, was developed to target the external domain. 89Zr J591 has prominent liver and cortical renal uptake but no significant urinary activity. Osborne et al. [33] studied 11 patients with localized prostate cancer using 89Zr J591. This agent detected 8/11 index lesions, but uptake was also seen in benign prostatic hyperplasia and imaging needed a delay of 5–7 days after injection to minimize background activity. Pandit-Taskar et al. [34] evaluated 89Zr J591 in 50 castration resistant prostate cancer patients with progressive metastatic disease and also found delayed imaging at 6–8 days was needed to best see lesions. They reported 95 % accuracy for detecting bone lesions, but only 60 % accuracy for visualizing soft tissue disease. One advantage of using the antibody scaffold is that it is relatively straightforward to attach therapeutic radionuclides as well. For instance, Vallabhajosula et al. [35] conducted five clinical phase I and II studies on prostate cancer patients with 177Lu J591 radiotherapy, primarily a beta-emitter. They demonstrated accurate targeting of known metastasis in >90 % of patients and PSA declines in >60 %. Antibodies clearly have the advantage of high affinity but have limitations in tissue penetration and require delayed imaging. Thus, small molecule agents targeting PSMA are of great interest.

In the early 2000s, small molecule PSMA antagonists began to be developed. An early trial using 124I MIP 1095, a small molecule PSMA inhibitor showed promising results and could be converted to a therapeutic agent by exchanging the 124I for 131I. Zechmann et al. [36] treated 28 patients with a single cycle with a mean dose of 4.8 GBq. PSA values decreased greater than 50 % in 17 patients and in the 13 patients with bone pain, 11 improved or resolved. However, there was concern about the possibility of de-iodination which would limit the specificity of the agent both for imaging and therapy.

68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PSMA (68Ga PSMA) ligand is a related small molecule PSMA antagonist that has quickly developed in Europe. Afshar-Oromeih et al. [37•] studied 319 prostate cancer patients with this agent. The study included primary, biochemical recurrence and metastatic cancers. Validation was not rigorous and confirmation was often clinically based. According to these standards, 68Ga PSMA detected 83 % of lesions and uptake correlated with PSA level and androgen deprivation therapy. Lesion-based analysis demonstrated a sensitivity of 76.6 %, specificity of 100 %, negative predictive value of 91.4 %, and positive predictive value of 100 %. Sensitivity went up to 88.1 % on patient-based analysis. Among 416 histologically confirmed lesions, there were 30 false negatives with 68Ga PSMA. Eiber et al. [38] retrospectively studied 248 men with BCR using 68Ga PSMA and detected a malignant lesion in 90 %. Detection rates improved with higher PSA levels and higher PSA velocity, but no significant association was seen with PSA doubling time or the use of antiandrogen therapy. 68Ga PSMA was more sensitive than conventional CT in detecting lymph node recurrences less than 8 mm in size. [39] 68Ga PSMA detected lesions not diagnosed on CT in 33 % of patients. A limitation of this study, like many others of this type, is that confirmatory data was only available in 37 % of cases. When rigorous histologic data is obtained, there is a considerable false negative rate for 68Ga PSMA. For instance, in high-risk prostate cancer patients scheduled for RP, Budaus et al. [40] studied 30 patients with presurgical 68Ga PSMA PET/CT and found only a 33 % sensitivity for metastatic lymph node detection confirmed by histopathology. It performed better at correctly identifying intraprostratic lesions in 93 % of patients. However, 68Ga PSMA consistently demonstrates very low false positive rates which is extremely important in patient management.

A natural question is whether 68Ga PSMA is superior to other PET agents. Only a limited amount of data is available. In a comparison of 18F choline and 68Ga PSMA, the latter detected more prostate cancer lesions, especially at lower PSA levels in biochemically recurrent patients. Afshar-Oromieh et al. [41] evaluated 37 patients with biochemical recurrence (mean PSA 11.1 ± 24.1) and found five patients without uptake on both methods, but 68Ga PSMA detected 78 lesions in 32 patients whereas FCH detected only 56 lesions in 26 patients. These lesions were also seen on 68Ga PSMA. Positive histological confirmation of 68Ga PSMA was obtained in seven patients. Metastatic lesions were seen in lymph nodes, bone, locally in the pelvis and in the soft tissue. FCH had a lower sensitivity for lymph node metastasis. Morigi et al. [42••] prospectively studied 38 BCR patients with both 68Ga PSMA and FCH and found 68Ga PSMA detected more disease at lower PSA levels and influenced clinical management more frequently. At PSA levels below 0.5 ng/mL, 68Ga PSMA had a detection rate of 50 % compared to 13 % for FCH. At PSA levels of 0.5–20 ng/mL, it showed detection rates of 69 vs 31 % for FCH. With PSA levels over 2 ng/mL, 68Ga PSMA detection improved to 86 % detection while FCH went up to 57 %. Ceci et al. [43] demonstrated that 68Ga PSMA detected sites of relapse in 74 % of patients and found a PSA level of 0.83 ng/mL or higher and a PSA doubling time of 6.5 months or shorter to be correlated with a higher likelihood of positive PET findings.

The possibility of using PSMA imaging to guide surgery has received attention. Maurer et al. [44] published a feasibility study on PSMA-radioguided surgery to find metastatic lymph nodes in five prostate cancer patients who had been imaged with 68Ga PSMA PET. Using an111In-labeled PSMA investigational compound, the intraoperative gamma probe found the lymph nodes seen on PET as well as additional nodes not captured on imaging, all with histologic confirmation. Hijazi et al. [45] studied 17 men with BCR or high-risk primary prostate cancer who underwent extended pelvic lymph node dissection after positive findings on 68Ga PSMA PET/CT. A median number of 10–12 lymph nodes were removed per patient. On histopathological examination, an overall total of two lymph nodes were false positive and one lymph node was false negative on PET.

A modified version of PSMA-HBED-CC, PSMA-617 has recently emerged as a potential therapeutic and diagnostic agent. Afshar-Oromieh et al. [46] published the first diagnostic experience of 68Ga PSMA-617 in humans. This agent requires a delay of 2–3 h post-injection compared to 1 h post-injection for the original agent. This scaffold enables the conjugation of a chelate that can hold a therapeutic radio-isotope. Ahmadzadehfar et al. [47] described treating 10 progressive, castration resistant metastatic prostate cancer patients with 177Lu PSMA-617. Follow-up after 8 weeks showed a PSA decline in seven patients and only mild side effects.

One question surrounding the use of 68Ga PSMA PET is its practicality. 68Ga is produced in a generator that must be purchased annually and then the agent is synthesized locally. This is of course possible for tertiary academic centers with the existing radiochemistry infrastructure but may not yet be feasible at the community hospital level. The 68 min half-life of 68Ga makes it difficult to ship from a central source. Therefore, an alternative 18F-based compound, 18F DCFBC, has been developed by Martin Pomper’s group (Fig. 1). Preliminary experience with this tracer is promising. In localized disease, there is no uptake in benign prostatic hyperplasia. In evaluating localized prostate cancer, Rowe et al. [48] studied 13 patients scheduled for prostatectomy who were imaged with 18F DCFBC. Dedicated prostate MR was also obtained in 12 patients and proved to be more sensitive in primary cancer detection than 18F DCFBC. The radiotracer was more specific for high grade, larger volume tumors than MRI with notable decreased activity in benign prostatic hypertrophy.

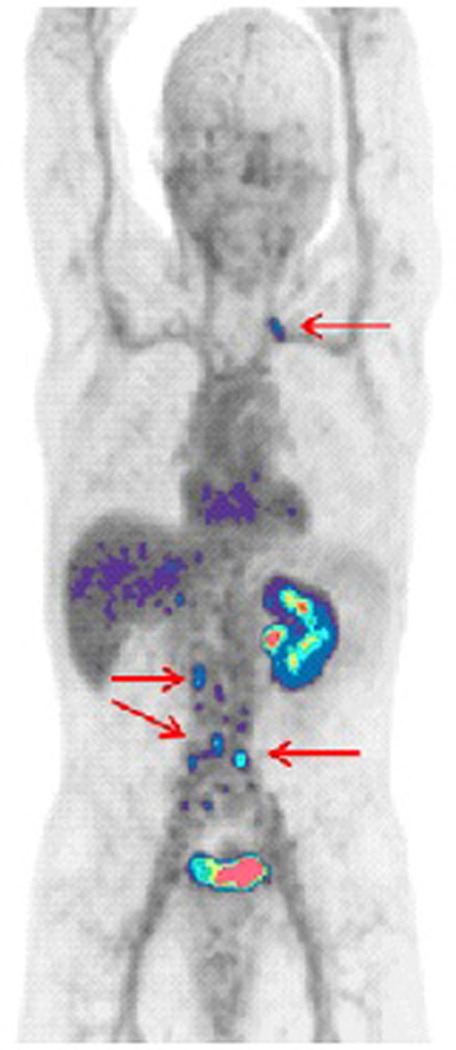

Fig. 1.

62-year-old patient with high-risk prostate cancer and no evidence of disease outside the prostate by radionuclide bone scan or CT, with PSA 14.06. 18F DCFBC demonstrates focal uptake in left supraclavicular and multiple retroperitoneal lymph nodes highly suggestive for metastatic disease

A second generation 18F agent, 18F DCFPyL, has recently been developed. This agent has improved characteristics over its predecessor, including a binding affinity five times stronger than18F DCFBC, significantly less blood pool activity and a reduced radiation exposure [49]. Dietlein et al. [50•] compared 18F DCFPyL to 68Ga PSMA in 14 prostate cancer patients with biochemical relapse and noted comparability in detecting lesions. 18F DCFPyL demonstrated higher SUVs and actually localized more lesions in three patients.

Thus, the PSMA-based agents appear to have excellent sensitivity and outstanding specificity for prostate cancer. Among all the agents discussed here, these properties make this agent most likely to become widely available in the clinic.

Opinion Statement

Prostate cancer is a prevalent malignancy for which current imaging methods underperform. Important gains could be made if reliable imaging were available for detecting localized disease, recurrent disease after therapy and accurately monitoring metastatic disease on therapy. Nuclear medicine research has developed many innovative agents to help address these issues by exploring unique targets such as cancer’s proliferative phospholipid cell membrane, amino acid uptake, and distinctive antigens and receptors. Novel tracers facilitate improved imaging of prostate cancer, but also usher in new compounds that could be useful for directing treatment as well. The current generation of PSMA-targeted PET agents clearly provides the most encouraging results. Further, theranostic imaging, whereby cancer could be both seen and treated, could transform the clinical landscape of prostate cancer management and provide more precise and curative treatment for a disease affecting many patients worldwide.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Prostate Cancer

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Liza Lindenberg, Peter Choyke, and William Dahut each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

Of importance

Of major importance

References

- 1.Ferlay JSI, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr 3/20/2014].

- 2.Hillner BE et al. Impact of F-18-fluoride PET in patients with known prostate cancer: initial results from the National Oncologic PET Registry. J Nucl Med 2014;55(4):574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillner BE et al. 18F-fluoride PET used for treatment monitoring of systemic cancer therapy: results from the National Oncologic PET Registry. J Nucl Med 2015;56(2):222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampath SC et al. Detection of osseous metastasis by F-18-NaF/F-18-FDG PET/CT versus CT alone. Clin Nucl Med 2015;40(3): E173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simoncic U et al. Comparison of NaF and FDG PET/CT for assessment of treatment response in castration-resistant prostate cancers with osseous metastases. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2015;13(1):E7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.••.Etchebehere E et al. Prognostic factors in patients treated with radium-223: the role of skeletal tumor burden on baseline 18F-fluoride-PET/CT in predicting overall survival. J Nucl Med 2015.This paper describes how NaF can be a predictive biomarker for overall survival and skeletal related events in patients treated with Ra.

- 7.Yu EY et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer bone metastasis response measured by 18F-fluoride PET after treatment with dasatinib and correlation with progression-free survival: results from American College of Radiology Imaging Network 6687. J Nucl Med 2015;56(3):354–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulsen MH et al. Spine metastases in prostate cancer: comparison of technetium-99m-MDP whole-body bone scintigraphy, F-18 choline positron emission tomography(PET)/computed tomography (CT) and F-18 NaF PET/CT. BJU Int 2014;114(6):818–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swinnen JV et al. Fatty acid synthase drives the synthesis of phospholipids partitioning into detergent-resistant membrane microdomains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003;302(4):898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madigan AA et al. Novel nuclear localization of fatty acid synthase correlates with prostate cancer aggressiveness. Am J Pathol 2014;184(8):2156–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mena E et al. 11C-Acetate PET/CT in localized prostate cancer: a study with MRI and histopathologic correlation. J Nucl Med 2012;53(4):538–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohsen B et al. Application of C-11-acetate positron-emission tomography (PET) imaging in prostate cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. BJU Int 2013;112(8):1062–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haseebuddin M et al. 11C-acetate PET/CT before radical prostatectomy: nodal staging and treatment failure prediction. J Nucl Med 2013;54(5):699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leisser A et al. Evaluation of fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer recurrence: SUVof [C]acetate PET as a prognostic marker. Prostate 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Dusing RW et al. Prostate-specific antigen and prostate-specific antigen velocity as threshold indicators in 11C-acetate PET/CTAC scanning for prostate cancer recurrence. Clin Nucl Med 2014;39(9):777–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umbehr MH et al. The role of 11C-choline and 18F-fluorocholine positron emission tomography (PET) and PET/CT in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2013;64(1): 106–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evangelista L et al. Choline PET or PET/CT and biochemical relapse of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med 2013;38(5):305–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.•.Beheshti M et al. Impact of 18F-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence: influence of androgen deprivation therapy and correlation with PSA kinetics. J Nucl Med 2013;54(6):833–40.This large prospective trial looked at FCH in BCR patients and examined its relationship to PSA and ADT.

- 19.Castellucci P et al. Early biochemical relapse after radical prostatectomy: which prostate cancer patients may benefit from a restaging 11C-Choline PET/CT scan before salvage radiation therapy? J Nucl Med 2014;55(9):1424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wondergem M et al. A literature review of 18F-fluoride PET/CT and 18F-choline or 11C-choline PET/CT for detection of bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer. Nucl Med Commun 2013;34(10):935–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccardo A et al. Value of fused 18F-Choline-PET/MRI to evaluate prostate cancer relapse in patients showing biochemical recurrence after EBRT: preliminary results. BioMed Res Int 2014;2014: 103718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceci F et al. Impact of 11C-choline PET/CT on clinical decision making in recurrent prostate cancer: results from a retrospective two-centre trial (vol 41, pg 2222, 2014). Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014;41(12):2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovacchini G et al. C-11-Choline PET/CT predicts prostate cancer-specific survival in patients with biochemical failure during androgen-deprivation therapy. J Nucl Med 2014;55(2):233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turkbey B et al. Localized prostate cancer detection with F-18 FACBC PET/CT: comparison with MR imaging and histopathologic analysis. Radiology 2014;270(3):849–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanni C et al. 18F-FACBC compared with 11C-choline PET/CT in patients with biochemical relapse after radical prostatectomy: a prospective study in 28 patients. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2014;12(2): 106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuster DM et al. Anti-3-F-18 FACBC positron emission tomography-computerized tomography and In-111-capromab pendetide single photon emission computerized tomography-computerized tomography for recurrent prostate carcinoma: results of a prospective clinical trial. J Urol 2014;191(5):1446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren J et al. The value of anti-1-amino-3–18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid PET/CT in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Acta Radiol 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beattie BJ et al. Pharmacokinetic assessment of the uptake of 16 beta-F-18-fluoro-5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone (FDHT) in prostate tumors as measured by PET. J Nucl Med 2010;51(2):183–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larson SM et al. Tumor localization of 16 beta-F-18-fluoro-5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone versus F-18-FDG in patients with progressive, metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2004;45(3):366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vargas HA et al. Bone metastases in castration-resistant prostate cancer: associations between morphologic CT patterns, glycolytic activity, and androgen receptor expression on PET and overall survival. Radiology 2014;271(1):220–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rathkopf DE et al. Phase I study of ARN-509, a novel antiandrogen, in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(28):3525–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertolini R et al. 18F-RB390: innovative ligand for imaging the T877A androgen receptor mutant in prostate cancer via positron emission tomography (PET). Prostate 2015;75(4):348–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osborne JR et al. A prospective pilot study of (89)Zr-J591/prostate specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography in men with localized prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2014;191(5):1439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandit-Taskar N et al. A phase I/II study for analytic validation of 89Zr-J591 immunoPET as a molecular imaging agent for metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallabhajosula S et al. Radioimmunotherapy of metastatic prostate cancer with 177Lu-DOTA-huJ591 anti prostate specific membrane antigen specific monoclonal antibody. Curr Radiopharm 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zechmann CM et al. Radiation dosimetry and first therapy results with a I-124/I-131-labeled small molecule (MIP-1095) targeting PSMA for prostate cancer therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014;41(7):1280–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.•.Afshar-Oromieh A et al. The diagnostic value of PET/CT imaging with the (68)Ga-labelled PSMA ligand HBED-CC in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015;42(2):197–209.This study included a large cohort of patients undergoing 68Ga to detect recurrent cancer with histologic corroboration in 42 patients.

- 38.Eiber M et al. Evaluation of hybrid (6)(8)Ga-PSMA ligand PET/CT in 248 patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Nucl Med 2015;56(5):668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giesel FL. et al. PSMA PET/CT with Glu-urea-Lys-(Ahx)-[Ga(HBED-CC)] versus 3D CT volumetric lymph node assessment in recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Budaus L et al. Initial Experience of Ga-PSMA PET/CT Imaging in high-risk prostate cancer patients prior to radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afshar-Oromieh A et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a Ga-68-labelled PSMA ligand and F-18-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014;41(1):11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.••.Morigi JJ et al. Prospective comparison of 18F-fluoromethylcholine versus 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT in prostate cancer patients who have rising PSA after curative treatment and are being considered for targeted therapy. J Nucl Med 2015;56(8):1185–90.This is a prospective study comparing the two tracers in patients with BCR and how they affected management.

- 43.Ceci F et al. (68)Ga-PSMA PET/CT for restaging recurrent prostate cancer: which factors are associated with PET/CT detection rate? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015;42(8):1284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maurer T et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-radioguided surgery for metastatic lymph nodes in prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015;68(3):530–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hijazi S et al. Pelvic lymph node dissection for nodal oligometastatic prostate cancer detected by Ga-PSMA-positron emission tomography/computerized tomography. Prostate 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afshar-Oromieh A et al. The novel theranostic PSMA-ligand PSMA-617 in the diagnosis of prostate cancer by PET/CT: biodistribution in humans, radiation dosimetry and first evaluation of tumor lesions. J Nucl Med 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmadzadehfar H et al. Early side effects and first results of radioligand therapy with (177)Lu-DKFZ-617 PSMA of castrate-resistant metastatic prostate cancer: a two-centre study. EJNMMI Res 2015;5(1):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rowe SP et al. (1)(8)F-DCFBC PET/CT for PSMA-based detection and characterization of primary prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2015;56(7):1003–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szabo Z et al. Initial evaluation of [(18)F]DCFPyL for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted PET imaging of prostate cancer. Mol Imaging Biol 2015;17(4):565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.•.Dietlein M et al. Comparison of [(18)F]DCFPyL and [(68)Ga]Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC for PSMA-PET imaging in patients with relapsed prostate cancer. Mol Imaging Biol 2015;17(4):575–84.This prospective trial evaluated the leading PSMA agents in detecting BCR and found them to be comparable.