Abstract

For some women, the experience of being sexually assaulted leads to increases in externalizing behaviors, such as problem drinking and drug use; for other women, the experience of being assaulted leads to increases in internalizing distress like depression or anxiety. It is possible that pre-assault personality traits interact with sexual assault to predict externalizing or internalizing distress. We tested whether concurrent relationships among personality, sexual assault, and distress were consistent with such a model. We surveyed 750 women just prior to their freshman year at a large public university. Consistent with our hypotheses, at low levels of negative urgency (the tendency to act rashly when distressed), sexual assault exposure had little relationship to problem drinking and drug use. At high levels of negative urgency, being sexually assaulted was highly associated with those externalizing behaviors. At low levels of internalizing personality traits, being assaulted had little relationship to depression and anxiety symptoms; at high levels of the traits, assault experience was highly related to those symptoms. Personality assessment could lead to more person-specific post-assault interventions.

Keywords: sexual trauma, alcohol, substance use, personality

This study addresses the significant impact that sexual assault victimization has on the mental health of college-aged women, integrating personality factors and trauma to understand maladaptive behavioral consequences. One important and unexplained phenomenon is that some women respond to the trauma of sexual assault with symptoms of externalizing disorders, most notably heavy alcohol consumption and illicit drug use, but others respond to the trauma with increases in internalizing dysfunction, such as major depression and generalized anxiety disorder (Kilpatrick, Ruggiero, Acierno, Saunders, Resnick, & Best, 2003; Ullman & Nadjowski, 2009). It is crucial to identify which women are likely to respond to the trauma in which way, given that (a) heavy alcohol consumption and drug use is associated with many problems, including increased risk of re-victimization (Ullman, Nadjowski, and Filipas, 2009); and (b) there are different empirically supported treatments for the two different kinds of dysfunction (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Linehan, 1993; Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, 2010).

Sexual Assault in Pre-College Samples

Sexual assault is a considerable source of concern for researchers and clinicians. The highest estimates of sexual assault are found in women aged 16–24, who are four times as likely to be sexually assaulted as any other age group (Danielson & Holmes, 2004). A recent study in pre-college girls found a staggering 51% of 7th-12th graders reporting some form of sexual abuse (unwanted kissing, touching, hugging, or other sexual contact; Young, Grey, & Boyd, 2009). A full 12% of adolescents reported rape, 6% reported forced oral sex, and 1% reported attempted rape. The repercussions of sexual assault are severe and can differ vastly depending on a number of factors; thus, the prevalence of assault in this group of women is particularly concerning. Major notable maladaptive outcomes of sexual assault are drinking problems, drug use, clinical anxiety, and clinical depression. These outcomes can be understood to reflect externalizing dysfunction (drinking problems, drug use) and internalizing dysfunction (clinical anxiety, clinical depression: Krueger & Markon, 2006; Miller, Greif & Smith, 2003; Miller, Kaloupek, Dillon, & Keane, 2004).

Outcomes Following Sexual Assault: Externalizing and Internalizing

Sexual assault is consistently associated with maladaptive drinking and drug abuse. Reports of alcohol dependence in women post-assault range from 13–49% while reports of use of illegal drug use range from 28–61% (Frank & Stewart, 1984; Frank, Turner, Stewart, Jacob, & West, 1981; Kilpatrick, Best, Veronen, Amick, Villeponteaux, et al., 1985; Petrak, Doyle, Williams, Buchan, & Forster, 1997). There is evidence that drinking is increased after assault at many different age ranges: childhood sexual abuse tends to lead to problem drinking, and alcohol initiation is more common in those who report sexual abuse (Combs, Smith, & Simmons, 2011; Wu, Bird, Liu, Duarte, Fuller, Fan, et al., 2010). Adult sexual abuse survivors report more overall drinking as well as more drinking problems than other women (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; Koss & Dinero, 1989; Ullman & Nadjowksi, 2009).

This, along with longitudinal evidence showing that women who abused alcohol and drugs or drugs alone were significantly more likely to be sexually assaulted, suggests a reciprocal relationship between the use of alcohol and drugs and sexual assault (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; Testa and Livingston, 2000). Though the single most consistent predictor of adult sexual assault is childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse is a close second (Gidycz, Coble, Latham, & Layman, 1993; Ullman, Nadjowski and Fillipas, 2009; White & Humphrey, 1997). This suggests that on top of the direct problems caused by substance abuse after sexual assault, there is significant risk of revictimization due to the combination of prior assault and substance abuse.

These forms of dysfunction are examples of what has been called “externalizing” dysfunction, which is often marked by impulsivity, high negative emotionality and aggression. It has been described as a subtype of post-trauma pathology in combat veterans as well as a major subtype of dysfunction in adolescents, normal adults, and alcoholic women (Miller et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2004; Settles, Fischer, Combs, Gunn, & Smith, 2012).

Internalizing dysfunction, on the other hand, is marked by low positive emotionality and high negative emotionality, and is often expressed as anxiety or depressive disorders (Krueger & Markon, 2006; Miller & Resick, 2007; Settles et al., 2012). Sexual abuse is highly associated with subsequent anxiety and depressive disorders (Breslau, 2002, Frazier, Anders, Perera, Tomich, Tennen, Park, et al., 2009; Petter & Whitehill, 1998). Reportedly, 13–51% of women develop depression after an assault, while 73–82% develop fear and/or anxiety (Acierno et al., 2002; Clum, Calhoun, & Kimerling, 2000; Dickinson, deGruy, Dickinson, & Candib, 1999; Frank & Anderson, 1987; Ullman & Siegel, 1993).

As shown here, there have been numerous studies relating sexual assault to both externalizing and internalizing maladaptive outcomes longitudinally; however, these studies have not yet explored the role of personality in the prediction of these outcomes (Campbell, Dworkin, & Cabral, 2009). There is a wealth of evidence for the influence of personality factors on the differentiation of internalizing and externalizing subtypes, however, and this will be summarized next.

Personality Correlates of Maladaptive Outcomes

The facts that only a portion of women who have experienced a sexual trauma go on to develop dysfunction and that the dysfunction varies in nature suggests the possibility that there are important individual differences contributing to risk for those negative sequelae to sexual trauma exposure. In particular, researchers have distinguished between traits that dispose individuals to externalizing dysfunction and those that dispose individuals to internalizing dysfunction (Settles et al., 2012).

Negative urgency is a personality trait that is understood not to just reflect dysregulated emotion, but to reflect the tendency to act rashly in response to distress (Combs & Smith, 2009; Cyders & Smith, 2008). There is increasing evidence that this trait predicts problem drinking and other externalizing behavioral dysfunction (Combs, Spillane & Smith, 2011; Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2009; Dick, Smith, Olausso, Mitchell, Leeman, O’Malley, et al., 2010; Fink, Anestis, Selby, & Joiner, 2010, Murphy & Murphy, 2011; Pryor, Miller, Hoffman, & Harding, 2009; Settles et al., 2012).

Other traits within the Neuroticism domain, including trait depression and trait anxiety, have been shown to relate to various forms of internalizing dysfunction, including major depression (Settles et al., 2012). This association between these two traits and internalizing dysfunction has been shown in 5th grade children, college students, and adult women diagnosed with major depression (Settles et al., 2012).

The Current Study

Our model holds that individual differences in negative urgency and trait depression/anxiety predict whether assaulted women are more likely to respond to trauma with engagement in externalizing or internalizing behaviors, respectively. To date, research has not investigated whether negative urgency, trait anxiety, or trait depression interact with a specific traumatic event to predict dysfunction.

The current study is the first test of this model; it involved a cross-sectional test of the relationships implied by the model. We tested two hypotheses. First, that negative urgency would interact with assault victimization to concurrently predict higher levels of drinking problems and illicit drug use, but that trait anxiety and trait depression would not. Second, that trait anxiety and trait depression would interact with assault victimization to predict higher levels of clinical anxiety and depression, but that trait negative urgency would not. Success of this cross-sectional test would provide a good rationale to test this model using a longitudinal design in which personality was assessed prior to victimization, to determine if pre-morbid personality interacts with assault victimization to predict subsequent dysfunctional behavior.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of women who participated in the study during the summer before they began college: all had been admitted to the University of Kentucky. In July, all incoming freshman women (1,800) received an e-mail with instructions for completing the web-based study. Of the 1,800 approached via email, 750 or 42% agreed to participate. All participants were at least 18-years-old. Almost 90% of participants identified as Caucasian, 7.7% identified as African-American, 2.8% identified as Asian, 0.4% identified as Native American, and 0.3% identified as Pacific Islander. When asked about estimated household income, 39.5% reported their household income as over $80,000 per year, 24.7% reported a household income of $40,000 to $80,000 per year, 15.2% reported an income of $10,000 to $40,000, 3.5% reported less than $10,000 per year, and 17.0% reported that they did not know.

Procedure

The study was available online and was administered in the summer of 2011 prior to the participants’ first day of move-in to the University. Eligibility was determined by questions regarding age (only students 18-years-old and older were included so as to ensure active consent), gender (only women), nature of enrollment (only what was termed traditional enrollment, defined as within three years of completing high school), and English-speaking ability. After indicating active consent, each participant was given access to the questionnaire, which took 1–2 hours to complete. Upon completion, participants were entered in a raffle to win one of 8 $250 gift cards to a local store. The University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board approved this procedure.

Measures

Demographic Information.

The participants filled out a demographic questionnaire obtaining information on estimated household income, age, ethnicity, parents’ education, and sexual orientation.

Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss & Oros, 1982).

The SES is a 14-item measure of different dimensions of sexual assault and rape. The experiences asked about range from unwanted touching to rape with a foreign object, and the questions reflect the participant’s age at which the experience occurred and number of times the experience has occurred. The SES is consistent with verbal reports of victimization at r= .73 (Koss & Gidycz, 1985); in this sample, internal consistency was strong with 〈=.81. A revised version of the SES was published in 2007 (Koss, Abbey, Campbell, Cook, Norris, et al., 2007), but we used the original version because, to date, it rests on a more extensive body of validity evidence. The wording was adjusted on some items to reduce the level of responsibility placed on the potential victims; for example, the phrase “sex play” was removed in favor of strict behavioral descriptions (“fondling, touching, petting”) and questions referring to intoxication were edited to reflect the possibility that the respondent was intoxicated prior to initially encountering an assailant (rather than mandating that the assailant provided alcohol/drugs to the respondent in order to qualify as assault).

Sexual assault was defined as an affirmative answer to any question on the SES; when dichotomizing the sexual assault variable, a 1 was assigned to any instance of unwanted touching, coerced/forced attempted intercourse and coerced/forced intercourse and a 0 was assigned to those who reported no instances of any behavior assessed on the SES. Dichotomizing responses to the measure of sexual assault exposure avoided the problem of zero inflation (more than half of the respondents reported no unwanted incidents) and positive skew. All participants received information about various ways to receive help from community or university clinics; those who disclosed a history of sexual assault received additional reminders about community resources.

Drinking Styles Questionnaire, Alcohol-Related Problems subscale (DSQ; Smith, McCarthy, & Goldman, 1995).

The Alcohol-Related Problems subscale of the DSQ includes problems related to arrests, vandalism, and fights with friends and family. Cronbach’s alpha in that sample was .84, and scores correlated .40 with collateral reports (Smith et al., 1995). In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Risky Behaviors Scale, Drug Use Items (RBS: Fischer & Smith, 2004).

The RBS is an 83 item Likert-type scale designed to assess frequency of engagement in risky behaviors. Seven items from the RBS were used that assess the target behavior of illegal drug use: used marijuana, cocaine, LSD, heroin, ecstasy, misused prescriptions, or other illegal drugs. To create a drug use score, responses for each drug were summed. Because this scale represents a summation of separate behaviors, internal consistency is not relevant and not reported.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996).

The BDI-II is a self-report measure that consists of 21 items used to assess depressive symptoms. The reliability and stability of the BDI have been reviewed extensively (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). In this sample, reliability of the scale was 〈=.93.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990).

The BAI is a 21-item measure of different symptoms of anxiety. Each item describes a somatic, panic-related, or subjective symptom. In this sample, reliability of the scale was 〈=.94.

UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale (Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2007).

The UPPS-P is a 44 item Likert type scale designed to assess five distinct personality traits that are related to impulsive behavior: negative urgency, positive urgency, lack of perseverance, lack of planning, and sensation seeking. In this study, we used the negative urgency scale only, which has been shown to have good internal consistency (in this study, 〈= .89). Negative urgency can be understood as the tendency to perform rash acts while in a negative mood. Example items include “When I feel bad, I will often do things I later regret in order to make myself feel better now,” and “I often make matters worse because I act without thinking when I am upset.”

Revised NEO Personality Inventory, Neuroticism domain (NEO-PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992).

The NEO-PI-R is a 240-item measure assessing the personality traits in the FFM. The NEO-PI-R has demonstrated good internal and external validity (Costa & McCrae, 1992). In the present study, we used the Depression and Anxiety facets of the Neuroticism domain (〈= .82 and .75 respectively; when combined, 〈= .87).

Data Analysis

After calculating frequencies of reported sexual assault experiences, drinking problems, drug use, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms, we computed correlation coefficients among all study variables. In order to test whether different personality traits provide differential concurrent prediction of adverse outcomes, we performed three primary multiple regressions, each with a different criterion variable: alcohol use, illegal drug use, and anxiety/depression symptom level. Predictors were the same for each regression: in the first step we entered negative urgency and trait anxiety/trait depression (the two were combined because they correlated r = .70). At step 2, we entered a dichotomous indicator of whether sexual assault has occurred since age 14. At step 3, we entered the interaction of time 1 negative urgency (centered) and the dichotomous sexual assault exposure variable, and also the interaction of time 1 trait anxiety/trait depression (centered) and the dichotomous sexual assault exposure variable.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

When asked to report mood disorder symptoms, 76.7% of participants endorsed at least one symptom of depression while 72.2% of participants endorsed at least one symptom of anxiety. In this sample, clinical anxiety and depression were significantly correlated at r=.68. When asked to report drinking problems, 49.7% of participants reported having experienced at least one problem due to drinking. When asked to report illegal drug use, 21.1% of participants reported engaging in at least one type of illegal substance use.

Sexual assault history was also reported: 58.9% of participants reported no sexual assault history, 17.6% of participants reported having experienced unwanted touching, 7.1% reported attempted unwanted intercourse, 5.8% of participants reported being pressured into unwanted intercourse, and 10.6% of participants reported having been forced by physical means into unwanted intercourse. These prevalence rates are consistent with past estimates of sexual assault history in pre-college women; frequencies and percentages are provided in Table 1 (Young et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Frequency and Percentage Rates of Sexual Assault in Study Sample.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| None | 355 | 58.9 |

| Unwanted Touching | 106 | 17.6 |

| Attempted Intercourse | 43 | 7.1 |

| Pressured Sex | 35 | 5.8 |

| Forced Sex/Rape | 64 | 10.6 |

N=759. Frequency adds up to 603 as 156 participants declined to answer.

All study variables were significantly associated with each other, excluding the relationship between trait anxiety/depression and drinking problems. All correlation coefficients describing the magnitude of the relationships between the variables are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations between Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Negative Urgency | -- | .57* | .29* | .28* | .23* | .44* |

| 2. Trait Anxiety/Depression | -- | .22* | .08 | .14* | .62* | |

| 3. Sexual Assault | -- | .34* | .23* | .29* | ||

| 4. Drinking Problems | -- | .33* | .15* | |||

| 5. Drug Use | -- | .26* | ||||

| 6. Clinical Anxiety/Depression | -- | |||||

Note. N = 750

p<.01.

Prediction of Alcohol Problems from Personality

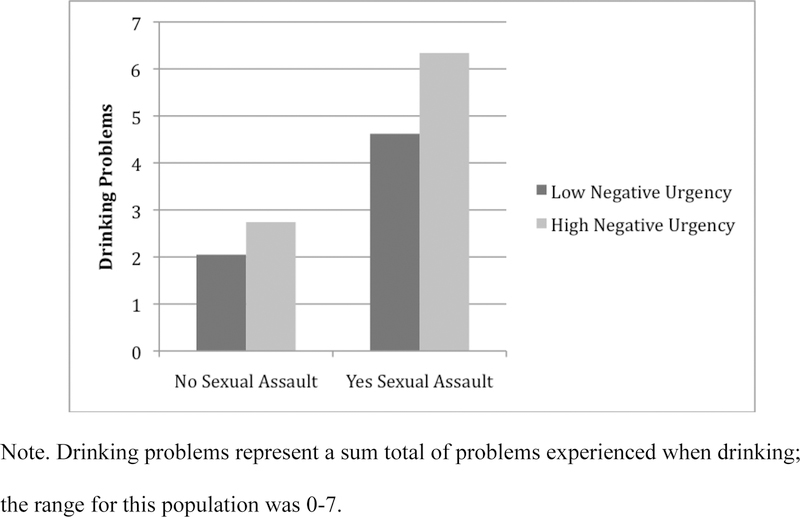

A full description of all multiple regression results can be found in Table 3. As seen in the table, both negative urgency and sexual assault exposure directly predicted drinking problems. The next step of the regression model tested two interaction effects simultaneously (negative urgency by sexual assault and trait anxiety/depression by sexual assault). Because that step produced significant incremental prediction (as seen in Table 3), we clarified the roles of the two interaction terms by performing two more separate regressions for each interaction term. The interaction between negative urgency and sexual assault explained significant additional variance (p < .01, unstandardized ß= .082) and provided an R2 change of .01. The nature of the interaction between negative urgency and sexual assault is such that at low levels of negative urgency (one standard deviation below the mean), presence or absence of sexual assault had some impact on the mean levels of drinking problems (unstandardized ß= .60, t=2.60, p =.01). At high levels of negative urgency (one standard deviation above the mean), having been assaulted was associated with significantly greater risk for drinking problems (unstandardized ß= 1.49, t = 5.89, p <.001; see Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the interaction).

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Predicting Outcomes From Traits, Sexual Assault, and the Interaction between Sexual Assault and Traits.

| β | R2 | R2 Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking Problems | |||

| Step 1. | .088 | -- | |

| Negative Urgency | .35* | ||

| Trait Anxiety/Depression | −.13 | ||

| Step 2. | .163 | .075* | |

| Sexual Assault | .28* | ||

| Step 3. | .175 | .013* | |

| Sexual Assault x Negative Urgency | .54* | ||

| Sexual Assault x Trait Anxiety/Depression | −.09 | ||

| Drug Use | |||

| Step 1. | .058 | -- | |

| Negative Urgency | .24* | ||

| Trait Anxiety/Depression | .01 | ||

| Step 2. | .081 | .024* | |

| Sexual Assault | .16* | ||

| Step 3. | .112 | .026* | |

| Sexual Assault x Negative Urgency | .76* | ||

| Sexual Assault x Trait Anxiety/Depression | −.08 | ||

| Clinical Anxiety/Depression | |||

| Step 1. | .403 | -- | |

| Negative Urgency | .12* | ||

| Trait Anxiety/Depression | .56* | ||

| Step 2. | .424 | .021* | |

| Sexual Assault | .15* | ||

| Step 3. | .442 | .018* | |

| Sexual Assault x Negative Urgency | .19 | ||

| Sexual Assault x Trait Anxiety/Depression | .51* | ||

Note. N=750.

p<.01.

Figure 1.

Interaction between Negative Urgency and Sexual Assault in the Prediction of Mean Levels of Drinking Problems.

In terms of the specific drinking problems most frequently endorsed, we found that in the absence of sexual assault, low levels of negative urgency were most commonly associated with feeling nauseated or vomiting after drinking, experiencing a hangover after drinking, and having blacked out while drinking. In the presence of sexual assault, those low in negative urgency reported similar problems, with the most commonly reported additional problems including getting in trouble with parents and not remembering events of the night while drinking. For those high on negative urgency in the absence of sexual assault, the most common drinking problems included nausea, vomiting, and experiencing a hangover. In the presence of sexual assault, those high on negative urgency reported experiencing the same problems; in addition, they also reported trouble with parents, blacking out, trouble with friends, and getting into physical fights.

Prediction of Drug Use from Personality

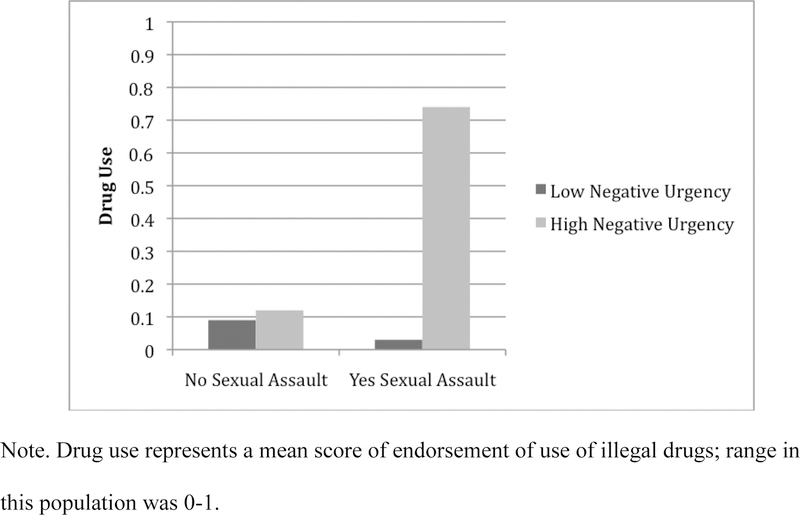

Similar results were found for the drug use outcome variable with the interaction step being highly predictive with an R2 change of .03 (p=.001). The interaction between negative urgency and sexual assault again accounted for the significant change and for the full R2 change (p=.001, unstandardized ß=.18). The nature of the interaction between negative urgency and sexual assault is such that at low levels of negative urgency, presence or absence of sexual assault was not associated with mean levels of substance abuse (unstandardized ß= .024, t = .05, p =.57). At high levels of negative urgency, having been assaulted was associated with significantly greater risk for substance abuse (unstandardized ß= .214, t = 5.28, p <.001; see Figure 2 for a visual depiction of the interaction). The interaction between trait anxiety/depression and sexual assault did not significantly predict substance abuse.

Figure 2.

Interaction between Negative Urgency and Sexual Assault in the Prediction of Mean Levels of Drug Use.

With respect to the nature of the drug use reported, we found that at low levels of negative urgency, whether or not assault occurred, there was almost no drug use. If drug use was reported, marijuana was used primarily. For those at high levels of negative urgency, in the absence of assault marijuana was also the only drug reported being used. In the presence of sexual assault, for those high on negative urgency, use of the following drugs was reported: marijuana, cocaine, LSD, heroin, ecstasy, other illegal drugs, and misuse of prescription drugs.

Prediction of Depression and Anxiety from Personality

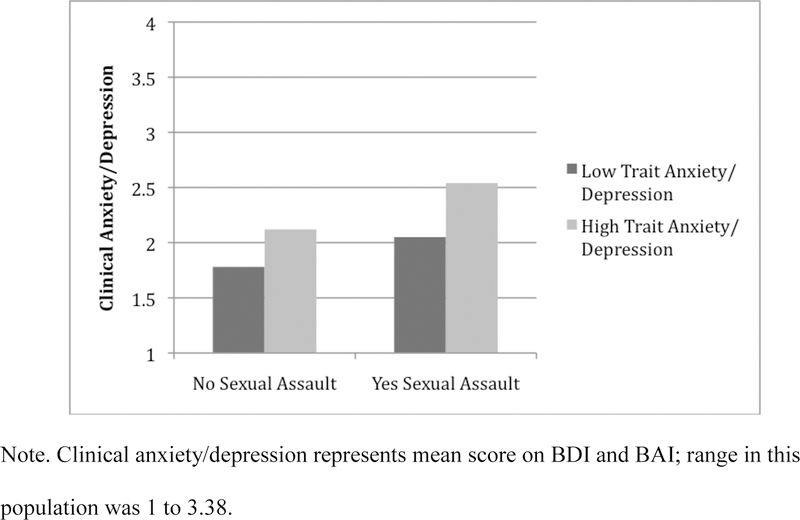

Regression analyses were performed with BDI and BAI scores separately, and results were virtually unchanged, so the internalizing outcomes were combined for ease of interpretation. In the regression equation, the interaction step was highly predictive of internalizing problems with an R2 change of .02 (p=.001). The interaction between sexual assault and trait anxiety/depression provided the significant increase in R2 and the R2 change of .02 (p=.001; unstandardized ß=.13). The nature of the interaction between trait anxiety/depression and sexual assault is such that at low levels of trait anxiety/depression, presence or absence of sexual assault had some impact on the mean levels of clinical anxiety/depression (unstandardized ß= .27, t = 8.22, p <.001). At high levels of trait anxiety/depression, having been assaulted was associated with significantly higher clinical anxiety/depression (unstandardized ß= .39, t = 10.63; p <.001; see Figure 3 for a visual depiction of the interaction). The interaction between negative urgency and sexual assault did not significantly predict clinical anxiety and depression.

Figure 3.

Interaction between Trait Anxiety/Depression and Sexual Assault in the Prediction of Mean Levels of Clinical Anxiety/Depression.

We explored the interactions in the different groups in order to better understand their clinical relevance. For those low on trait anxiety/depression and who were not sexually assaulted, the most common reports were of less energy, more sleeping, more fatigue, feeling nervous, and feeling dizzy or lightheaded. The presence of sexual assault was associated with each of the same symptoms, with additional reports of finding it hard to relax. For those high on trait anxiety/depression, the absence of sexual assault was associated with feeling scared, fear of dying, difficulty breathing, loss of control, feeling shaky, feeling nervous, fear of the worst, trouble with concentration, changes in appetite, irritability, worthlessness and thoughts of suicide. For those high on trait anxiety/depression, the presence of sexual assault was associated with each of the above symptoms, as well as frequent reports of the following: hot/cold sweats, face flushed, feeling faint or lightheaded, hands trembling, feeling terrified, heart pounding/racing, feeling unsteady, feeling unable to relax, loss of interest in sex, fatigue, sleep more, less energy, feeling restless, crying a lot feeling self-critical, loss of confidence, feeling guilty, loss of pleasure, feelings of failure, feeling sad and feeling down about the future.

Discussion

The impact of sexual assault can be long lasting and lead to further distress; in some cases, certain outcomes are heavily correlated with revictimization. Thus, having the ability to predict different sequelae of assault based on person-specific traits may have important implications for treatment and prevention. This cross-sectional study suggests the value of studying transactions between personality characteristics and assault victimization to understand maladaptive post-assault behaviors. We intend to conduct such a study using a prospective design with these participants.

Women who were high on negative urgency and who were assaulted were significantly higher on drinking problems as well as on reports of illegal drug use than were other women. The finding of an interaction between negative urgency and victimization is quite important: to understand externalizing behavior in assaulted women it is important to consider both the fact of the assault and the personality make-up of the victim. The negative urgency – assault interaction was specific to externalizing dysfunction: it did not predict clinical anxiety/depression scores. In contrast, the interaction of trait anxiety/trait depression and assault victimization concurrently predicted depression and anxiety symptom level, but did not predict externalizing behaviors. To understand internalizing behavior in assaulted women one must again consider both the fact of the assault and the personality structure of the victim.

The acquired preparedness model (Combs & Smith, 2009; Corbin, Iwamoto, & Fromme, 2011; Settles et al., 2010; Smith & Anderson, 2001) holds that personality traits lead individuals to be predisposed to react in specific ways to learning events and then to develop learning-specific dysfunction according to person-environment transactions. For example, people who are high on negative urgency who also hold positive expectancies about alcohol use tend to binge drink, those who hold positive expectancies about the mood-altering benefits of eating tend to binge eat, and those who hold positive expectancies about smoking tend to smoke (Combs et al., 2010; Combs et al., 2012; Pearson et al., 2012; Settles et al., 2010). It is possible that the experience of sexual assault acts as an acute traumatic learning experience, predisposing women to develop symptomatology related to their personality traits (internalizing or externalizing). Thus, it is possible that women who are high in negative urgency already typically act in rash ways when they are upset while women who are high in trait anxiety and depression already withdraw or display high arousal when they are upset, and that these dispositions combine with the experience of sexual assault to lead to maladaptive levels of externalizing or internalizing behaviors. This set of possibilities should be investigated with longitudinal designs.

Clinically, there appear to be severe ramifications for those high on our studied traits who experience assault. In all three groups, outcomes are similar for those low on the traits who have and have not experienced assault and those high on the traits who have not experienced assault; however, for those who have experienced assault and are high on our studied traits, we see more types of problems as well as higher prevalence of problems in general. For example, while use of marijuana alone was seen in those low on negative urgency and in the presence and absence of assault as well as high on negative urgency in the absence of assault, those high on negative urgency who were assaulted reported use of marijuana as well as every other type of substance. In this set of women, sexual assault was not only related to higher levels of overall drug use, but increased variability in drug use. These data also provide an interesting look into the problem of revictimization. As described before, substance use is the second strongest predictor of victimization after prior victimization; the current results suggest that there may be a cyclical process occurring for women with high levels of certain personality traits. If victimization indeed leads to higher levels of substance use, the implications for potential revictimization are clear. Also, many, if not all, interventions for women after trauma focus on the trauma itself without addressing personality and its role in the development of maladaptive outcomes; treatment approaches that also consider personality may well be beneficial. There currently are well-validated treatments for emotion-driven externalizing dysfunction (Linehan, 1993) and for internalizing dysfunction (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001) that could be incorporated into existing post-assault treatments as a function of victim personality. In the long run, provision of personality-specific post-assault interventions could reduce maladaptive outcomes, perhaps even reducing the rate of revictimization (Angelo, Miller, Zoellner, & Feeny, 2008).

There are, of course, limitations to this study. First, the model we described involves hypotheses concerning prospective prediction; however, this study is cross-sectional. This initial cross-sectional test is valuable, because the findings (a) indicate the merit of investigating the model using more expensive longitudinal designs and (b) suggest new avenues for intervention development. However, the current data do not reflect a temporal prediction of relationships between the variables. Clearly, more rigorous longitudinal tests will prove useful. Second, all data were collected by self-report questionnaire using a web-based format; there was thus no opportunity to clarify questions or responses. However, confidential self-report is likely the most effective way to get valid and valuable data for several reasons: 1) Women are more likely to underreport sexual assaults in a face-to-face or interview situation (Ongena & Wil Dijsktra, 2007); 2) Questionnaire data is highly reliable and often more so than interview data (Testa, Livingston, & VanZile-Tamsen, 2005); 3) As this is a difficult topic for many women, being able to answer the questions and receive information on therapeutic services in their own home may have provided stronger feelings of security and safety than if they had been asked to come in, either for questionnaire data collection or for an interview. Third, the sample is a predominantly white pre-college (and largely middle to upper middle class) population of women. These results are thus generalizable to a specific subset of young women, and it would be helpful to explore these relationships in a more diverse sample.

Sexual assault is an issue that creates significant acute and lasting harm for women of all ages, but particularly for young women. The women in this study were about to enter college, an environment in which maladaptive externalizing behavior like substance abuse is common, perhaps even nurtured rather than extinguished, and maladaptive internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression often go unnoticed. By better understanding the mechanisms through which different women develop these different dysfunctions after assault, we can hopefully work toward preventing such outcomes. Though the best-case scenario would be to prevent assault in the first place, we can also target predicted behaviors and personality traits to reduce post-assault distress as much as possible.

Acknowledgments

Funding: In part, this research was supported by NIAAA grant RO1AA016166 to Gregory T. Smith and the Mary Byron Fellowship funded by the Center for Research on Violence Against Women at the University of Kentucky.

References

- Acierno R, Brady K, Gray M, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, & Best CL (2002). Psychopathology following interpersonal violence: A comparison of risk factors in older and younger adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 8, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Angelo FN, Miller HE, Zoellner LA, & Feeny. (2008). “I need to talk about it:” A qualitative analysis of trauma-exposed women’s reasons for treatment choice. Behavior Therapy, 39, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Steer RA (1990). Beck Anxiety Inventory manual San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). BDI-II manual (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Garbin MG (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-25 years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N (2002). Epidemiologic studies of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other psychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 923–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Dworkin E, & Cabral G (2009). An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10, 225–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, & Ollendick TH (2001). Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 685–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum GA, Calhoun KS, & Kimerling R (2000). Associations among symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and self-reported health in sexually assaulted women. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188, 671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, & Smith GT (2009). The acquired preparedness model of risk for Binge Eating Disorder: Integrating nonspecific and specific risk processes. In Chambers N (Ed.), Binge Eating: Psychological Factors, Symptoms, and Treatment (55–86). New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Smith GT, & Simmons JR (2011). Distinctions between two expectancies in the prediction of maladaptive eating behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Spillane NS, & Smith GT (2011). Core dimensions of dysfunction: Toward a diagnostic system based on advances in clinical science. In Columbus F (Ed.), Advances in Psychology Research (141–164). New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Spillane NS, Stark B, Caudill L, & Smith GT (2012). The Acquired Preparedness risk model applied to smoking in 5th grade children. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 331–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Iwamoto DK, & Fromme K (2011). A comprehensive longitudinal test of the acquired preparedness model for alcohol use and related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72, 602–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). NEO PI-R. Professional manual Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 807–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K Rainer S, & Smith GT (2009). The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction, 104, 193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson CK, & Holmes MM (2004). Adolescent sexual assault: an update of the literature. Current Opinion Obstetrics and Gynecology, 16, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith GT, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, & Sher K (2010). Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology, 15, 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson LM, deGruy FV, Dickinson WP, & Candib LM (1999). Health-related quality of life and symptom profiles of female survivors of sexual abuse in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine, 8, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink EL, Anestis MD, Selby EA, & Joiner TD (2010). Negative urgency fully mediates the relationship between alexithymia and dysregulated behaviors. Personality and Mental Health, 4, 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, & Smith GT (2004). Deliberation affects risk taking beyond sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, & Anderson BP (1987). Psychiatric disorders in rape victims: Past psychiatric history and current symptomatology. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28, 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, & Stewart BD (1984). Depressive symptoms in rape victims: A revisit. Journal of Affective Disorders, 7, 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Turner SM, Stewart BD, Jacob M, & West D (1981). Past psychiatric symptoms and the response to sexual assault. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 22, 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Anders S, Perera S Tomich P, Tennen H, Park C, & Tashiro T (2009). Traumatic events among undergraduate students: Prevalence and associated symptoms. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Coble CN, Latham L, & Layman MJ (1993). Sexual assault experience in adulthood and prior victimization experiences: a prospective analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 17, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, & Wilson KG (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, & Best CL (1997). A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 834–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D, Ruggiero K, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick H, and Best C (2003). Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Best CL, Veronen LJ, Amick AE, Villeponteaux LA, & Ruff GA (1985). Mental health correlates of criminal victimization: A random community survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 866–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S; Norris J, Testa C, Ullman S, West C, & White J (2007). Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, & Dinero TE (1989). Discriminant analysis of risk factors for sexual victimization among a national sample of college women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, & Gidycz CA (1985). Sexual Experiences Survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 422–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, & Oros CJ (1982). Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 455–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, & Markon KE (2006). Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 111–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, & Cyders MA (2006). The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior (Technical Report) West Lafayette: Purdue University. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, & Resick PA (2007). Internalizing and externalizing subtypes in female sexual assault survivors: Implications for the understanding of complex PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 38, 58–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Greif JL & Smith AA (2003). Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire profiles of veterans with traumatic combat exposure: Internalizing and externalizing subtypes. Psychological Assessment, 15, 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Kaloupek DG, Dillon AL, & Keane TM (2004). Externalizing and internalizing subtypes of combat-related PTSD: A replication and extension using the PSY-5 Scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, & Murphy J (2011). Living in the here and now: interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology, 219, 527–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongena YP, & Dijkstra W (2007). A model of cognitive processes and conversational principles in survey interview interaction. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CM, Combs JL, Zapolski TCB, & Smith GT (2012). A longitudinal transactional risk model for early eating disorder onset. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 707–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrak J, Doyle A, Williams L, Buchan L, & Forster G (1997). The psychological impact of sexual assault: A study of female attenders of a sexual health psychology service. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 12, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Petter LM, & Whitehill DL (1998). Management of female sexual assault. American Family Physician, 58, 920–926, 929–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor LR, Miller JD, Hoffman BJ, & Harding HG (2009). Pathological personality traits and externalizing behavior. Personality and Mental Health, 3, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Combs JL, Gunn RL, & Smith GT (2012). Clarifying the role of negative affect in externalizing disorder: The differential roles of emotional distress and negative urgency in depression and alcoholism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121 160–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, & Smith GT (2010). Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT & Anderson KG (2001). Adolescent risk for alcohol problems as acquired preparedness: A model and suggestions for intervention. In Monti PM, Colby SM, and O’Leary TA (Eds.) Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, & Goldman MS (1995). Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Livingston JA (2000). Alcohol and sexual aggression: reciprocal relationships over time in a sample of high-risk women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, & VanZile-Tamsen C (2005). The impact of questionnaire administration mode on response rate and reporting of consensual and nonconsensual sexual behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, & Nadjowski CJ (200a). Correlates of serious suicidal ideation and attempts in female adult sexual assault survivors. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 39, 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Nadjowski CJ, & Filipas HH (2009). Child sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use: Predictors of revictimization in adult sexual assault survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 18, 367–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, & Siegal JM (1993). Victim-offender relationship and sexual assault. Violence and Victims, 8, 121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JW, and Humphrey JA (1997). A longitudinal approach to the study of sexual assault.” In Schwartz M (Ed.), Researching Sexual Violence Against Women (2–42). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Bird HR, Liu X, Duarte CS, Fuller C, Fan B, Shen S, & Canino GJ (2010). Trauma, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol-use initiation in children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 326–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Grey M, & Boyd CJ (2009). Adolescents’ experiences of sexual assault by peers: prevalence and nature of victimization occurring within and outside of school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1072–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, & Smith GT (2010). The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment, 17, 116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]