Abstract

During Herbert Tabor's tenure as Editor-in-Chief from 1971 to 2010, JBC has published many seminal papers in the fields of chromatin structure, epigenetics, and regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. As of this writing, more than 21,000 studies on gene transcription at the molecular level have been published in JBC since 1971. This brief review will attempt to highlight some of these ground-breaking discoveries and show how early studies published in JBC have influenced current research. Papers published in the Journal have reported the initial discovery of multiple forms of RNA polymerase in eukaryotes, identification and purification of essential components of the transcription machinery, and identification and mechanistic characterization of various transcriptional activators and repressors and include studies on chromatin structure and post-translational modifications of the histone proteins. The large body of literature published in the Journal has inspired current research on how chromatin organization and epigenetics impact regulation of gene expression.

Keywords: RNA polymerase, transcription, chromatin, nucleosome, epigenetics, transcription factor, histone acetyltransferase, nucleoprotein, TATA-binding protein

Introduction

The fields of transcription and chromatin structure were largely separate in 1971 when Herbert Tabor became Editor-in-Chief of JBC. During the ensuing years, studies on gene regulation in eukaryotes have focused on the fact that our genes are packaged into a nucleoprotein complex called chromatin, a complex of DNA with histone proteins and a multitude of structural proteins and enzyme complexes involved in transcription (as well as DNA synthesis, DNA repair, and recombination). The interplay between chromatin structure and how the transcription apparatus accesses genes for the productive synthesis of mRNA and various noncoding RNAs has proved to be central to the regulation of gene expression. Studies on transcription at the molecular level have been the subject of more than 21,000 publications in JBC since 1971, and searching for “transcription” and “chromatin” reveals more than 2300 JBC publications during this time (according to Web of Science). It is impossible to do justice to such a large collection of papers, so this review will reflect the author's bias toward the application of biochemical methods to understand transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Molecular characterization of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes began with the identification of the three forms of RNA polymerase and the accessory factors required for basal transcription, ultimately leading to current studies on the interplay between chromatin, epigenetic mechanisms, and transcriptional regulation. This review will attempt to highlight some of the milestones in the field that have occurred under Herbert Tabor's tenure at JBC and point out how earlier studies have impacted current research being reported in JBC.

Multiple forms of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in eukaryotes

Prokaryotes have a single species of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase that can be regulated by its association with various accessory factors, such as σ factors (1). In contrast, there are three major nuclear RNA polymerases (pol)2 in eukaryotic cells known to be responsible for the synthesis of rRNA (RNA pol I), mRNAs and various noncoding RNAs (RNA pol II), and 5S rRNA and tRNAs, among other small noncoding RNAs (RNA pol III), respectively. Two groups, one headed by Robert Roeder (Rockefeller University, New York) and the other headed by Pierre Chambon (Strasbourg, France), made the seminal discovery that DNA-dependent RNA synthesis activity in cell-free extracts from eukaryotic cells could be chromatographically separated into three peaks, which differ in their protein subunit compositions and sensitivity to the inhibitor α-amanitin (for an early review, see Ref. 2). Although these initial findings were published in other journals (2, 3), the majority of Roeder's contributions describing the isolation of the three enzyme classes from various organisms and cell types, their biochemical and enzymatic properties, abundance (4, 5), as well as subunit compositions (6–8) were published in JBC. These ground-breaking papers set the stage for further understanding of the biochemical basis for RNA synthesis in eukaryotic cells.

Accessory factors are needed for accurate transcription

Although the biochemically isolated RNA pol species were highly active in vitro using either genomic DNA (4) or the synthetic polymer poly[d(A-T)] (5) as templates, these assays only measured incorporation of radioactive precursors into random RNA species. When researchers tried to use protein-free DNA and purified RNA polymerases to transcribe discrete RNAs, the experiments failed. Specific genes could be transcribed from isolated nuclei or chromatin templates, suggesting the cell-free experiments were missing accessory factors in addition to the RNA pols that are necessary for promoter recognition, initiation, and perhaps termination of transcription by each of the RNA polymerases. One landmark paper published in JBC described the specific and accurate transcription of adenovirus VA-RNA in chromatin or nuclei isolated from virus-infected cells by both endogenous and exogenous RNA pol III (9). Accurate transcription from cloned gene templates (5S rRNA genes and adenovirus VA genes) was also obtained with RNA pol III supplemented with cell-free extracts (10), strongly suggesting the requirement for cellular factors in addition to RNA pol III for accurate transcription. Such extracts were then fractionated by chromatographic methods, and distinct cellular factors were identified for both RNA pol III (11) and RNA pol II (12), but at this point these factors were simply chromatographic fractions, and further biochemical studies were needed to identify the actual protein species that comprised these factors. Similar studies on RNA pol I began with transcription of cloned rRNA genes in extracts from Xenopus oocyte nuclei (13) and yeast (14) and lead to the identification of distinct factors necessary for RNA pol I transcription in vitro in mammalian cells (15) and in yeast (16).

RNA pol II core transcription machinery

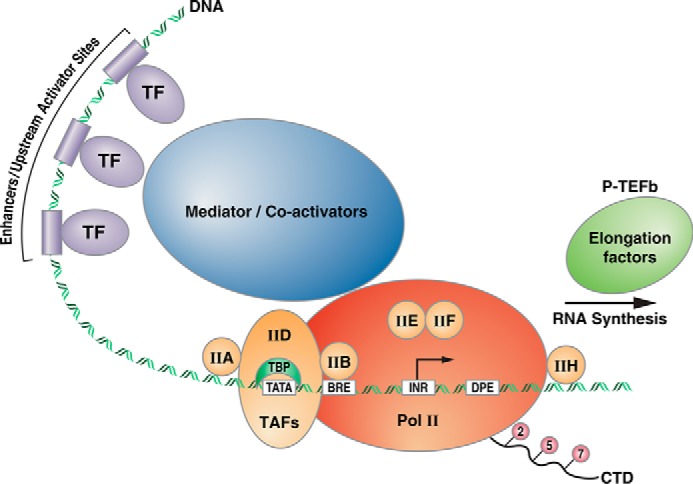

In a remarkable series of papers, Roeder, Reinberg, and co-workers identified the core components of the mammalian RNA pol II transcription machinery (transcription factors TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, and TFIIF, known as general TFs or GTFs) and documented the order in which each of these GTFs bind an RNA pol II core promoter element (i.e. the DNA sequences immediately adjacent to the transcription start-sites of an mRNA-coding gene) to recruit RNA pol II and initiate transcription (17). Studies in other organisms, such as yeast by Kornberg and co-workers (18, 19) and Drosophila by Kadonaga and co-workers (20), lead to broadly similar conclusions but with subtle differences between species. Subsequently, additional factors were identified, such as the multisubunit factor TFIIH (21, 22). A number of studies published in JBC reported the identification of the polypeptide subunits of these TFs (23, 24), and other studies documented the interactions between the various GTFs and roles of the GTFs in assembly of the RNA pol II preinitiation complex (PIC) (25, 26). Fig. 1 provides a simplistic overview of the DNA sequence elements and protein factors involved in RNA pol II transcription. In the first-generation model for assembly of the PIC, the TATA box–binding protein (TBP) subunit of the GTF TFIID binds TATA elements located ∼30 bp upstream of the transcription start-site (Fig. 1) and leads to the recruitment of the other GTFs. However, this is an idealized model that only applies to a limited number of genes because most promoters lack TATA elements, and the details of PIC assembly therefore depend upon the sequence composition of the particular promoter/gene under investigation (17). In support of this view, early studies with multiple promoter elements pointed out the different GTF requirements for basal levels of transcription (27). Investigations into the roles played by the various subunits of the GTFs in assembly of the PIC continue to be a subject of interest in the JBC. For example, JBC papers have investigated the roles played by the TBP-associated subunits of TFIID (the TAFs) in recruitment of RNA pol II and communication with other TFs (28, 29). Although core promoter elements and the GTFs (Fig. 1) were largely identified and characterized over a decade ago, recent studies reported in JBC describe new features of core promoters, such as a TFIIA recognition element (IIARE (30)). The IIARE was reported to enhance TFIIA binding and recruitment of GTFs and pol II and to enhance transcription in vitro, at least for TATA-containing promoters. Early studies also established that there was an energy requirement for transcription initiation by RNA pol II (31). Identification of the various steps in the transcription cycle that utilize the energy of ATP hydrolysis continues to be an active area of investigation reported in JBC (Ref. 32 and references therein).

Figure 1.

Schematic of a hypothetical RNA polymerase II promoter. Upstream activator sites and enhancers are bound by a variety of transcription factors, composed of DNA-binding domains (shown as cylinders on the DNA) and activation domains (shown as circles). These proteins serve to recruit co-activators, which can act on chromatin to facilitate transcription complex assembly (see below) or mediator, a large multisubunit complex that communicates with and is part of the core transcription machinery. The first step in assembly of the PIC is the association of the TBP subunit of TFIID with a TATA element, located ∼30 bp upstream of the transcription start site (arrow). TFIID also contains TAFs that communicate with and respond to upstream activators. Other core components of the PIC are depicted (TFs IIA, IIB, etc.). BRE refers to a TFIIB-response element, and INR refers to the initiator element, which are DNA sequences found in various RNA pol II promoters. DPE is a downstream promoter element. TFIIH and the P-TEFb elongation factor both contain kinase activities that act on the CTD of RNA pol II at serine residues within heptad repeats. These phosphorylation events are associated with initiation and elongation phases of the transcription cycle (see text).

In addition to the GTFs, another multisubunit complex was identified and shown to mediate communication between activating TFs (at enhancer and upstream activator sequences) and the GTFs and RNA pol II, hence the name “Mediator” for this complex (Fig. 1). Although Mediator was first identified in yeast by Kornberg and co-workers (33, 34), other studies in JBC have probed the role of Mediator in higher organisms and shown that Mediator facilitates recruitment of RNA pol II through the general TFs, such as TFIIB (35). Originally thought to be separate from the GTFs and RNA pol II, Mediator is now considered to be an integral component of the PIC. Structural insights into Mediator function have recently been reviewed in JBC (36).

Preinitiation complex formation for RNA pol I- and RNA pol III-transcribed genes

Similar to findings for RNA pol II, fractionation of cell-free extracts led to the identification of TFs required for accurate transcription of rRNA by RNA pol I (15, 37) and 5S rRNA and tRNAs by RNA pol III (11). For RNA pol I, two TFs are involved, SL1 and UBF, whereas for RNA pol III, tRNA genes require TFIIIB and TFIIIC and additionally the zinc-finger protein TFIIIA for the 5S rRNA genes. Mechanistic studies on assembly of the preinitiation complexes for both RNA pol I (15, 37) and RNA pol III (38–40) were published in JBC. One of the major surprises in studies of the basal transcription machinery was the requirement for TBP for transcription by each of the RNA pols. However, TBP is localized within different multisubunit complexes for each polymerase (41). TBP is found in TFIID (for RNA pol II, Fig. 1; and the SAGA complex (42)), TFIIIB (for RNA pol III (43)), and SL1 (for RNA pol I), along with different sets of TAFs. Polymerase-specific TAFs were found to interact with other components of the transcription machinery for genes transcribed by each RNA polymerase (43–45). Another common feature of the transcription complexes for genes transcribed by each RNA pol is the stability of the TBP-containing complex (TFIID, SL1, or TFIIIB), which persists at promoter DNA (at least in vitro) through multiple rounds of transcription. This is likely due to the stability of TBP on both TATA-containing and TATA-less promoter elements (46) but also to the associated factors, including the TAFs and other GTFs ((47) for pol III/TFIIIB).

Phosphorylation of the largest subunit of RNA pol II as a major regulatory event in transcription

The largest subunit of RNA pol II contains at its C terminus tandem repeats of the consensus sequence Tyr–Ser–Pro–Thr–Ser–Pro–Ser, first identified by Corden et al. (48) in a seminal paper published in another journal. Following this, a series of papers from Dahmus and co-workers published in the JBC established that mammalian mRNA synthesis is carried out by a phosphorylated form of RNA pol II (49) and that the transition from initiation to elongation is mediated by differential phosphorylation events (50). Phosphorylation within this C-terminal domain (CTD) at Ser-2, Ser-5, and Ser-7 has been associated with different stages of the transcription cycle, and numerous papers in JBC have reported identification of both the kinases and phosphatases involved (51–54). Unphosphorylated RNA pol II is recruited to the PIC; Ser-5 phosphorylation is associated with initiation of transcription, mediated by the CDK7 subunit of TFIIH (in both yeast (22, 55) and mammalian cells (54, 56)), and Ser-2 phosphorylation is associated with elongation, mediated by the positive elongation factor P-TEFb (52). Early studies in yeast suggested that Ser-7 phosphorylation was similar to Ser-5 phosphorylation both in terms of the kinase involved and its role in transcription initiation (55), but more recent work suggests that all three phosphorylation events may be required for transcription elongation (57). Recent studies have also focused on the accessory proteins that interact with P-TEFb, such as the bromodomain-containing protein BRD4 that is also involved in Ser-2 phosphorylation and transcription elongation (see below and Ref. 58). Besides RNA pol II, phosphorylation of many transcription factors has been shown to be key regulatory events (for example, cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) (59) and NF-κB (60) among many similar studies).

In addition to phosphorylation, the RNA pol II CTD is subject to glycosylation by O-GlcNAc (61), and it is reasonable to speculate that interplay between CTD modification states could be involved in transcriptional regulation (61, 62). In support of this, the O-GlcNAc transferase OGT has been found associated with the RNA pol II CTD as part of the PIC, and reducing OGT levels with shRNA blocks transcription (63, 64). Several transcriptional activators have also been found to be glycosylated (62); for example, O-GlcNAc regulates the FoxO1 transcription factor in response to glucose (65), providing insights into nutrient control of transcription (63).

Activators and repressors

Numerous studies published in JBC have identified DNA sequence elements upstream and downstream from core promoters that are required for “activated” transcription, as well as the protein factors that bind such elements. A search of Web of Science with the terms “transcription” and “activator” yields nearly 2800 such citations in the JBC since 1971, so a comprehensive review of this literature is beyond the scope of this historical perspective. Nevertheless, two highly cited examples of such studies are worth mentioning: these are the identification of antioxidant response elements that respond to the transcription factor NRF2 (NF-E2-related factor 2) (66) and the identification of the pluripotency factors OCT4 and SOX2 as regulators of the homeodomain pluripotency factor Nanog (67). These and numerous similar studies show binding of regulatory factors to their cognate DNA elements both in vitro and in cells, and they usually use RNA-silencing methods to demonstrate the critical role of these factors in target gene regulation. Similar to gene activation, mechanisms involved in gene repression have also been a hot topic in JBC, with more than 1400 papers since 1971. For example, Kouzarides and co-workers (68) described the methyl-CpG–binding protein 2 (MeCP2) as a link between DNA methylation and gene repression through recruitment of co-repressor complexes containing histone-modifying enzymes.

Chromatin, central to our understanding of transcriptional regulation

As noted earlier, the genetic material in eukaryotic cells is packaged with histone and nonhistone chromosomal proteins, and studies in JBC have probed virtually all aspects of chromatin organization, histone post-translational modifications, and the role of chromatin in transcriptional regulation. The basic subunit of chromatin organization is the nucleosome, consisting of 147 bp of DNA, wrapped around an octamer of the core histones, consisting of two dimers of H2A and H2B, and a tetramer of two copies of H3 and H4 (Fig. 2). Nucleosomes are joined together via linker DNA of variable length (generally 40–60 bp, with variations between tissues within an organism and differences between species) along with histone H1. Early studies focused on the nucleosome and chromatin higher-order structures. Questions that were addressed in numerous JBC papers included whether (and how) DNA sequence determines nucleosome positioning (69), how histones are deposited on DNA during nucleosome assembly (70), the structure of particular genetic loci in chromatin, and the relationship between transcription and accessibility to nuclease digestion (see Ref. 71 among many others).

Figure 2.

Histone post-translational modifications control chromatin accessibility and transcription. A, transcriptionally active euchromatin is associated with acetylation of the core histones, whereas transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin is associated with other histone marks, such as methylation at histone H3 lysine 9 and 27. Various HDACs, HATs, histone methylases (HMTs), and demethylases control the transitions between euchromatin and heterochromatin. B, atomic structure of the nucleosome core particle with N-terminal tails of the core histones indicated by dashed lines (not seen in the X-ray structure). Nucleosome core particle is shown with histone H3 in blue, H4 in green, H2A in yellow, and H2B in red. The histone tails are involved in inter-nucleosome interactions, where the N-terminal tail of histone H3 contacts the histone octamer of an adjacent nucleosome. Histone tails also provide binding sites for the readers, writers, and erasers of the histone code, involved in both gene activation and repression. The blue and magenta structures are two HATs, modeled interacting with histone tails. Adjacent nucleosomes connected by linker DNA are modeled. Images generously provided by Dr. E. Soragni (Scripps Research) and Dr. K. Luger (University of Colorado, Boulder).

An important area of investigation in chromatin research has been histone post-translational modifications and the effects of such modifications on nucleosome and chromatin organization and gene expression, topics that have received considerable attention in the pages of JBC. These modifications include acetylation and methylation of the ϵ-amino groups of lysine residues, particularly within the ∼20–30 amino acids of the N termini of histones H3 and H4, phosphorylation of serine residues, ubiquitinylation and glycosylation (Fig. 2A). These modifications have been proposed to constitute a “histone code” for gene activity (hypothesized by Allis and co-workers and reviewed in Ref. 72), where the enzymes responsible for modification are the “writers” of the code; proteins that bind these modified histones are the “readers,” and enzymes that remove the modifications are the “erasers.”

Acetylation

An early study from Allfrey and co-workers (73) documented that sodium butyrate caused histones to become highly acetylated through inhibition of histone deacetylation. Numerous subsequent studies identified the histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes in various organisms (the erasers of the acetylation code (74)), and inhibitors of their activity (75, 76), as well as efforts to identify the histone acetyltransferases (HATs, the writers of the acetylation code) and their substrate specificities (77–80). The identification of trichostatin A (75) and valproic acid (76) as HDAC inhibitors are two highly cited papers in the Journal, with over 1500 and over 1100 citations, respectively, as of this writing (according to Web of Science). Mechanistic studies of the HDACs have also revealed links between these enzymes and gene regulation (81, 82). Transcriptional coactivator complexes possess intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity, providing a direct link between chromatin acetylation and transcriptional activation (83, 84). Various signaling molecules also impact histone acetylation (85). Readers of the acetyl histone code include BRD4, a protein that recognizes acetylated lysine residues and communicates with P-TEFb and RNA pol II to facilitate productive transcription elongation (for recent JBC papers, see Refs. 58, 86).

Just how chromatin structure is affected by acetylation has been intensely investigated. Biophysical studies showed that acetylation has no major effect on nucleosome structure (87); however, other studies showed that chromatin fiber solubility and sensitivity to nuclease digestion are greatly increased on histone acetylation (88). Many of these studies relied on simple methods, such as salt gradient dialysis, to reconstitute either single nucleosomes on short DNA fragments or utilized arrays of well-positioned nucleosomes. Robert Simpson's discovery that a sea urchin 5S rRNA gene contained a strong nucleosome positioning sequence provided a DNA substrate for many such studies (69, 70, 89). Acetylation has been proposed to weaken histone–DNA interactions, but studies with these defined arrays of nucleosomes showed that acetylation has more pronounced effects outside of the nucleosome core particle (90) and largely on inter-nucleosome contacts resulting in a more extended chromatin conformation (89). Recent studies have examined the roles of particular histone acetylation events in the transcription cycle. For example, O'Malley and co-workers (86) reported that H3K9 acetylation is involved in the switch between transcription initiation to elongation. Understanding just how the “histone code” regulates gene expression continues to be an active area of investigation in JBC.

Acetyl-lysine reader proteins, such as BRD4 and TRIM24, have received considerable attention due to their involvement in expression of MYC and other cancer-promoting oncogenes (91, 92). BRD4 is a member of the bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) family and, as noted above, plays an important role in transcriptional elongation. Because of its association with cancer, BET inhibitors have been widely investigated as potential therapeutics. In one JBC study, Jung et al. (91) mapped the regions of the BRD4 responsible for interactions with acetylated peptides derived from histone H4 and showed that similar amino acid residues in the protein were responsible for binding the potent BRD4 inhibitor JQ1. Studies such as this will certainly facilitate the development of BET inhibitors. Similarly, TRIM24 (tripartite motif-containing protein 24) is a reader of H3K23ac, and inhibitors are also being developed as anti-cancer agents (92).

Histone methylation is linked to both gene activation and repression

Methylation of histone lysine residues is associated with either gene activation (for example, H3K4me3 (trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4) at or near transcription start sites) or gene repression (H3K9 and K27 di- and trimethylation). Studies published in JBC have focused on both the enzymes responsible for these methylation events (the methyltransferases) and the activators and repressors that recognize histone methylation states to effect gene activation or repression (93–97). In the case of H3K4me3 at active promoter elements, this mark serves to recruit the nucleosome remodeling factor NURF (see below and Ref. 98). Methylated H3K9(me2/3) is recognized by heterochromatin proteins, such as HP1, leading to recruitment of co-repressor complexes (97). Components of PRC2 (polycomb-repressive complex 2) recognize methylated H3K27 leading to transcriptional repression (99). Methylation at other residues of the core histones, such as H3K36 and H3K79, is linked to the elongation phase of the transcription cycle (100). Thus, “readers” of the histone code discriminate between repressive and activating histone methylation marks to either repress transcription or to recruit co-activators or chromatin remodeling factors. Understanding the cross-talk between the various histone modification states and their role in the transcription cycle continues to be a subject of great interest in the Journal. For example, Gates et al. (86) showed that although H3K4me3 is involved in transcription initiation, H3K9ac mediates the switch from the initiation to elongation phases by promoting release of paused pol II by recruitment of an elongation complex.

Similar to studies with inhibitors of acetyl-lysine readers (91, 92), both the histone lysine methyltransferases (KMT) and methylated histone readers have been the subject of anti-cancer drug development efforts (101, 102). In one recent study, Coussens et al. (101) used nucleosome substrates to screen compound libraries for inhibitors of the KMT NSD2, which is overexpressed or mutated in a variety of human cancers. Active molecules were found to bind the KMT nuclear receptor-binding SET domain. This assay platform will enable future oncology drug development efforts where either chromatin-modifying enzymes or the readers of such modifications are the targets. As for the KMTs, readers of methylated histone marks are often mutated or overexpressed in cancer and other diseases. One such class of readers of H3K4me3 is the plant homeodomain (PHD) zinc finger proteins (such as Ing2 and the mix lineage leukemia proteins), and a study in JBC identified macrocyclic calixarenes as potent inhibitors to disrupt binding of PHD fingers to H3K4me3 in vitro and in vivo (102). Such studies will also facilitate future oncology drug development efforts.

Phosphorylation, glycosylation, and ubiquitinylation of histones

A paper describing phosphorylation of a particular subtype of histone H2A (encoded by the H2A gene family member X, H2AX), at serine 139 upon DNA damage, is one of the highest cited JBC papers of all time, with 3095 citations as of this writing (according to Web of Science). This modification, called γ-H2AX, has been linked to various cellular processes, including apoptosis (103), and a kinase responsible for this modification has been identified as ATM (for ataxia telangiectasia mutate, (104)). Regions of chromatin containing γ-H2AX are likely more open to the DNA repair machinery thus providing a link between this histone modification and chromatin structure. In addition to γ-H2AX, another important histone phosphorylation event is H3S10p, which is coupled to mitotic chromosome condensation (105). The kinases and phosphatases that regulate this modification have also been identified (106). In addition, histone H3 can be phosphorylated at tyrosine 41 as well as threonine 45, and a recent study in JBC reported that these modifications regulate DNA accessibility in the nucleosome (107). Another modification of histone H3 is O-GlcNAc glycosylation at Thr-28, which is cell cycle-regulated. This modification also regulates mitotic phosphorylation at Ser-10, providing another example of cross-talk between histone modification states (63, 108).

Histone H2B can be modified by conjugation of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to lysine residues. Whereas most cellular functions of ubiquitin are involved in protein stability and turnover through the proteasome (109), H2B ubiquitinylation is required for cell cycle progression, telomere gene silencing, and transcriptional repression (109). An important JBC paper showed that ubiquitinylation of H2B at lysine 123 is the signal for H3 methylation, leading to gene silencing at yeast telomeres (110). Another small protein modification of histones is sumoylation (by the small ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO), where this modification of histone H4 regulates chromatin compaction (111). H4 sumoylation weakens internucleosome interactions leading to more open chromatin, and hence it may be involved in transcriptional activation. Sumoylation can also occur on other chromatin-associated proteins, and a recent study from Barton and co-workers (92) described the cross-talk between histone acetylation and sumoylation of the acetyl/methyl reader protein TRIM24. As noted above, TRIM24 is aberrantly expressed in many cancers, so the link between TRIM24 sumoylation and chromatin association may be vital to understand the role of TRIM24 in oncogenesis.

Chromatin remodeling complexes

Numerous studies published in JBC have concerned chromatin-remodeling complexes, multisubunit complexes, some of which utilize the energy of ATP hydrolysis to catalyze the movement or displacement of nucleosomes. Chromatin remodeling is an essential process for both preinitiation complex assembly and transcription initiation and elongation (112, 113). Although these complexes were first identified in yeast, mammalian remodeling complexes have been identified (113–115), and their mechanisms of action have been intensively investigated (115, 116). For example, the NURF complex has been shown to slide the histone octamer along the DNA in steps of 10 bp or one helical turn of the DNA on the surface of the octamer (116). ATP-dependent chromatin assembly factors such as Asf1 (anti-silencing factor 1) in yeast (117) and RSF (remodeling and spacing factor) in higher organisms (115) have been shown to evict nucleosomes from gene promoters allowing active transcription complexes to form. One other important aspect of chromatin remodeling is the incorporation of histone variants into nucleosomes. For example, the ATP-dependent remodeler SWR1 is responsible for the exchange of canonical H2A–H2B dimers with dimers containing the H2A variant H2A.Z. Studies have shown that histone acetylation facilitates SWR1-mediated histone dimer exchange (118). Nucleosomes containing H2A.Z are located at promoters, which are susceptible to eviction on transcriptional activation. Structural studies have indeed shown that oligonucleosomes containing H2A.Z are destabilized compared with canonical nucleosomes (119), likely allowing for eviction by other remodeling complexes. Mechanistic studies of chromatin-remodeling complexes continue to be of interest to the JBC. A recent study by Formosa and co-workers (120) described the role of the high-mobility group B (HMGB) domain in nucleosome assembly and reorganization by FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription), which is an ATP-independent chromatin remodeler. High-mobility group domains are minor-groove DNA-binding domains that bend DNA, and this study showed that both histone and DNA binding are involved in chromatin remodeling.

In vitro reconstitution of active chromatin templates

Various viral, yeast, and mammalian promoter elements have been reconstituted in defined systems to analyze the requirements for active transcription by RNA pol II (115, 121). In these systems, chromatin assembly on a defined DNA sequence is mediated by one of the ATP-dependent chromatin assembly complexes containing a histone chaperone, the core histones, a transcriptional activator (such as the artificial activator Gal4–VP16), and the basal transcription factors discussed above (or unfractionated cell-free extracts). One finding of importance is that acetyl-CoA is required for preinitiation complex assembly in these in vitro systems (122, 123), providing further evidence that protein acetylation is required for active transcription. Mass spectrometry was used in one study to identify histone H3K9, H3K27, H3K36, and H3K37 as sites of p300-catalyzed acetylation in promoter-proximal nucleosomes in such a reconstituted system (123). Chromatin reconstitution from defined components continues to be an area of active investigation, and a recent report from Kadonaga and co-workers (124) described the refinement of such a system for ATP-dependent assembly of chromatin using a histone chaperone (Drosophila nucleoplasmin–like protein (dNLP)), an ATP-remodeling enzyme (imitation switch (ISWI)), core histones, and various DNA substrates. This experimental resource will benefit future detailed mechanistic studies on the relationship between chromatin and transcription. While studies on the role of chromatin in transcriptional regulation have been ongoing for nearly 5 decades, this remains an area of great interest to the readers of JBC. Stay tuned for more!

Acknowledgments

I thank E. Soragni and K. Luger for images in Fig. 2 and C. Goodman for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 5R01-NS062856, 5R01-EY026490, and 1R01-EY029166 and by BioMarin Pharmaceutical. This JBC Review is part of a collection honoring Herbert Tabor on the occasion of his 100th birthday. The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- pol

- polymerase

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- PIC

- preinitiation complex

- TBP

- TATA box–binding protein

- TF

- transcription factor

- GTF

- general transcription factor

- TAF

- TBP-associated subunit of TFIID

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- BET

- bromodomain and extra-terminal domain

- KMT

- histone lysine methyltransferase

- PHD

- plant homeodomain

- HAT

- histone acetyltransferase.

References

- 1. Sekine S., Tagami S., and Yokoyama S. (2012) Structural basis of transcription by bacterial and eukaryotic RNA polymerases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 22, 110–118 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chambon P. (1975) Eukaryotic nuclear RNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 44, 613–638 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.003145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roeder R. G., and Rutter W. J. (1969) Multiple forms of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in eukaryotic organisms. Nature 224, 234–237 10.1038/224234a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roeder R. G. (1974) Multiple forms of deoxyribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleic acid polymerase in Xenopus laevis. Isolation and partial characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 241–248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schwartz L. B., Sklar V. E., Jaehning J. A., Weinmann R., and Roeder R. G. (1974) Isolation and partial characterization of the multiple forms of deoxyribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleic acid polymerase in the mouse myeloma, MOPC 315. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 5889–5897 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwartz L. B., and Roeder R. G. (1974) Purification and subunit structure of deoxyribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleic acid polymerase I from the mouse myeloma, MOPC 315. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 5898–5906 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwartz L. B., and Roeder R. G. (1975) Purification and subunit structure of deoxyribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleic acid polymerase II from the mouse plasmacytoma, MOPC 315. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 3221–3228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sklar V. E., and Roeder R. G. (1976) Purification and subunit structure of deoxyribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleic acid polymerase III from the mouse plasmacytoma, MOPC 315. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1064–1073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jaehning J. A., and Roeder R. G. (1977) Transcription of specific adenovirus genes in isolated nuclei by exogenous RNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 8753–8761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weil P. A., Segall J., Harris B., Ng S. Y., and Roeder R. G. (1979) Faithful transcription of eukaryotic genes by RNA polymerase III in systems reconstituted with purified DNA templates. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 6163–6173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Segall J., Matsui T., and Roeder R. G. (1980) Multiple factors are required for the accurate transcription of purified genes by RNA polymerase III. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11986–11991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matsui T., Segall J., Weil P. A., and Roeder R. G. (1980) Multiple factors required for accurate initiation of transcription by purified RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11992–11996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkinson J. K., and Sollner-Webb B. (1982) Transcription of Xenopus ribosomal RNA genes by RNA polymerase I in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 14375–14383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swanson M. E., and Holland M. J. (1983) RNA polymerase I-dependent selective transcription of yeast ribosomal DNA. Identification of a new cellular ribosomal RNA precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 3242–3250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schnapp A., and Grummt I. (1991) Transcription complex formation at the mouse rDNA promoter involves the stepwise association of four transcription factors and RNA polymerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 24588–24595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riggs D. L., Peterson C. L., Wickham J. Q., Miller L. M., Clarke E. M., Crowell J. A., and Sergere J. C. (1995) Characterization of the components of reconstituted Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase I transcription complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6205–6210 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Müller F., Demény M. A., and Tora L. (2007) New problems in RNA polymerase II transcription initiation: matching the diversity of core promoters with a variety of promoter recognition factors. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14685–14689 10.1074/jbc.R700012200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flanagan P. M., Kelleher R. J., Feaver W. J., Lue N. F., LaPointe J. W., and Kornberg R. D. (1990) Resolution of factors required for the initiation of transcription by yeast RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 11105–11107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sayre M. H., Tschochner H., and Kornberg R. D. (1992) Reconstitution of transcription with five purified initiation factors and RNA polymerase II from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 23376–23382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wampler S. L., Tyree C. M., and Kadonaga J. T. (1990) Fractionation of the general RNA polymerase II transcription factors from Drosophila embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 21223–21231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flores O., Lu H., and Reinberg D. (1992) Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II. Identification and characterization of factor IIH. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 2786–2793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svejstrup J. Q., Feaver W. J., LaPointe J., and Kornberg R. D. (1994) RNA polymerase transcription factor IIH holoenzyme from yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28044–28048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ranish J. A., and Hahn S. (1991) The yeast general transcription factor TFIIA is composed of two polypeptide subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19320–19327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takagi Y., Komori H., Chang W. H., Hudmon A., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., and Kornberg R. D. (2003) Revised subunit structure of yeast transcription factor IIH (TFIIH) and reconciliation with human TFIIH. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43897–43900 10.1074/jbc.C300417200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Imbalzano A. N., Zaret K. S., and Kingston R. E. (1994) Transcription factor (TF) IIB and TFIIA can independently increase the affinity of the TATA-binding protein for DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 8280–8286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Killeen M., Coulombe B., and Greenblatt J. (1992) Recombinant TBP, transcription factor IIB, and RAP30 are sufficient for promoter recognition by mammalian RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 9463–9466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parvin J. D., Shykind B. M., Meyers R. E., Kim J., and Sharp P. A. (1994) Multiple sets of basal factors initiate transcription by RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18414–18421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu S. Y., and Chiang C. M. (2001) TATA-binding protein-associated factors enhance the recruitment of RNA polymerase II by transcriptional activators. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34235–34243 10.1074/jbc.M102463200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feigerle J. T., and Weil P. A. (2016) The C terminus of the RNA polymerase II transcription factor IID (TFIID) subunit Taf2 mediates stable association of subunit Taf14 into the yeast TFIID complex. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 22721–22740 10.1074/jbc.M116.751107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang J., Zhao S., He W., Wei Y., Zhang Y., Pegg H., Shore P., Roberts S. G. E., and Deng W. (2017) A transcription factor IIA-binding site differentially regulates RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription in a promoter context-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 11873–11885 10.1074/jbc.M116.770412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sawadogo M., and Roeder R. G. (1984) Energy requirement for specific transcription initiation by the human RNA polymerase II system. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 5321–5326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fishburn J., Galburt E., and Hahn S. (2016) Transcription start site scanning and the requirement for ATP during transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 13040–13047 10.1074/jbc.M116.724583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gustafsson C. M., Myers L. C., Beve J., Spåhr H., Lui M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., and Kornberg R. D. (1998) Identification of new mediator subunits in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30851–30854 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takagi Y., and Kornberg R. D. (2006) Mediator as a general transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 80–89 10.1074/jbc.M508253200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baek H. J., Kang Y. K., and Roeder R. G. (2006) Human mediator enhances basal transcription by facilitating recruitment of transcription factor IIB during preinitiation complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15172–15181 10.1074/jbc.M601983200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harper T. M., and Taatjes D. J. (2018) The complex structure and function of mediator. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 13778–13785 10.1074/jbc.R117.794438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keener J., Josaitis C. A., Dodd J. A., and Nomura M. (1998) Reconstitution of yeast RNA polymerase I transcription in vitro from purified components. TATA-binding protein is not required for basal transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33795–33802 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carey M. F., Gerrard S. P., and Cozzarelli N. R. (1986) Analysis of RNA polymerase III transcription complexes by gel filtration. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 4309–4317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bieker J. J., Martin P. L., and Roeder R. G. (1985) Formation of a rate-limiting intermediate in 5S RNA gene transcription. Cell 40, 119–127 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90315-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bieker J. J., and Roeder R. G. (1986) Characterization of the nucleotide requirement for elimination of the rate-limiting step in 5 S RNA gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9732–9738 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. White R. J., and Jackson S. P. (1992) The TATA-binding protein: a central role in transcription by RNA polymerases I, II and III. Trends Genet. 8, 284–288 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90255-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martinez E., Kundu T. K., Fu J., and Roeder R. G. (1998) A human SPT3-TAFII31-GCN5-L acetylase complex distinct from transcription factor IID. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23781–23785 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Poon D., and Weil P. A. (1993) Immunopurification of yeast TATA-binding protein and associated factors. Presence of transcription factor IIIB transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 15325–15328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Friedrich J. K., Panov K. I., Cabart P., Russell J., and Zomerdijk J. C. (2005) TBP-TAF complex SL1 directs RNA polymerase I pre-initiation complex formation and stabilizes upstream binding factor at the rDNA promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29551–29558 10.1074/jbc.M501595200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Furukawa T., and Tanese N. (2000) Assembly of partial TFIID complexes in mammalian cells reveals distinct activities associated with individual TATA box-binding protein-associated factors. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29847–29856 10.1074/jbc.M002989200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Coleman R. A., and Pugh B. F. (1995) Evidence for functional binding and stable sliding of the TATA binding protein on nonspecific DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13850–13859 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Librizzi M. D., Brenowitz M., and Willis I. M. (1998) The TATA element and its context affect the cooperative interaction of TATA-binding protein with the TFIIB-related factor, TFIIIB70. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 4563–4568 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Corden J. L., Cadena D. L., Ahearn J. M. Jr., and Dahmus M. E. (1985) A unique structure at the carboxyl terminus of the largest subunit of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 7934–7938 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cadena D. L., and Dahmus M. E. (1987) Messenger RNA synthesis in mammalian cells is catalyzed by the phosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 12468–12474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Payne J. M., Laybourn P. J., and Dahmus M. E. (1989) The transition of RNA polymerase II from initiation to elongation is associated with phosphorylation of the carboxyl-terminal domain of subunit IIa. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 19621–19629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Payne J. M., and Dahmus M. E. (1993) Partial purification and characterization of two distinct protein kinases that differentially phosphorylate the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase subunit IIa. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 80–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marshall N. F., Peng J., Xie Z., and Price D. H. (1996) Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27176–27183 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chambers R. S., and Dahmus M. E. (1994) Purification and characterization of a phosphatase from HeLa cells which dephosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26243–26248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trigon S., Serizawa H., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C., Jackson S. P., and Morange M. (1998) Characterization of the residues phosphorylated in vitro by different C-terminal domain kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6769–6775 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim M., Suh H., Cho E. J., and Buratowski S. (2009) Phosphorylation of the yeast Rpb1 C-terminal domain at serines 2, 5, and 7. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26421–26426 10.1074/jbc.M109.028993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Serizawa H., Conaway J. W., and Conaway R. C. (1994) An oligomeric form of the large subunit of transcription factor (TF) IIE activates phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain by TFIIH. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20750–20756 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu J., Fan S., Lee C. J., Greenleaf A. L., and Zhou P. (2013) Specific interaction of the transcription elongation regulator TCERG1 with RNA polymerase II requires simultaneous phosphorylation at Ser-2, Ser-5, and Ser-7 within the carboxyl-terminal domain repeat. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10890–10901 10.1074/jbc.M113.460238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang W., Prakash C., Sum C., Gong Y., Li Y., Kwok J. J., Thiessen N., Pettersson S., Jones S. J., Knapp S., Yang H., and Chin K. C. (2012) Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) regulates RNA polymerase II serine 2 phosphorylation in human CD4+ T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 43137–43155 10.1074/jbc.M112.413047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Du K., and Montminy M. (1998) CREB is a regulatory target for the protein kinase Akt/PKB. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32377–32379 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sakurai H., Chiba H., Miyoshi H., Sugita T., and Toriumi W. (1999) IκB kinases phosphorylate NF-κB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30353–30356 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kelly W. G., Dahmus M. E., and Hart G. W. (1993) RNA polymerase II is a glycoprotein. Modification of the COOH-terminal domain by O-GlcNAc. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10416–10424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Comer F. I., and Hart G. W. (2000) O-Glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Dynamic interplay between O-GlcNAc and O-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29179–29182 10.1074/jbc.R000010200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lewis B. A., and Hanover J. A. (2014) O-GlcNAc and the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34440–34448 10.1074/jbc.R114.595439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ranuncolo S. M., Ghosh S., Hanover J. A., Hart G. W., and Lewis B. A. (2012) Evidence of the involvement of O-GlcNAc-modified human RNA polymerase II CTD in transcription in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23549–23561 10.1074/jbc.M111.330910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Housley M. P., Rodgers J. T., Udeshi N. D., Kelly T. J., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Puigserver P., and Hart G. W. (2008) O-GlcNAc regulates FoxO activation in response to glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16283–16292 10.1074/jbc.M802240200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jain A., Lamark T., Sjøttem E., Larsen K. B., Awuh J. A., Øvervatn A., McMahon M., Hayes J. D., and Johansen T. (2010) p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22576–22591 10.1074/jbc.M110.118976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rodda D. J., Chew J. L., Lim L. H., Loh Y. H., Wang B., Ng H. H., and Robson P. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24731–24737 10.1074/jbc.M502573200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fuks F., Hurd P. J., Wolf D., Nan X., Bird A. P., and Kouzarides T. (2003) The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4035–4040 10.1074/jbc.M210256200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. FitzGerald P. C., and Simpson R. T. (1985) Effects of sequence alterations in a DNA segment containing the 5 S RNA gene from Lytechinus variegatus on positioning of a nucleosome core particle in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 15318–15324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hansen J. C., van Holde K. E., and Lohr D. (1991) The mechanism of nucleosome assembly onto oligomers of the sea urchin 5 S DNA positioning sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 4276–4282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wood W. I., and Felsenfeld G. (1982) Chromatin structure of the chicken β-globin gene region. Sensitivity to DNase I, micrococcal nuclease, and DNase II. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 7730–7736 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Allis C. D. (2015) “Modifying” my career toward chromatin biology. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15904–15908 10.1074/jbc.X115.663229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Boffa L. C., Vidali G., Mann R. S., and Allfrey V. G. (1978) Suppression of histone deacetylation in vivo and in vitro by sodium butyrate. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 3364–3366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Carmen A. A., Rundlett S. E., and Grunstein M. (1996) HDA1 and HDA3 are components of a yeast histone deacetylase (HDA) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15837–15844 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yoshida M., Kijima M., Akita M., and Beppu T. (1990) Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 17174–17179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Phiel C. J., Zhang F., Huang E. Y., Guenther M. G., Lazar M. A., and Klein P. S. (2001) Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer, and teratogen. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36734–36741 10.1074/jbc.M101287200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wiktorowicz J. E., and Bonner J. (1982) Studies on histone acetyltransferase. Partial purification and basic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 12893–12900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Travis G. H., Colavito-Shepanski M., and Grunstein M. (1984) Extensive purification and characterization of chromatin-bound histone acetyltransferase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 14406–14412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sobel R. E., Cook R. G., and Allis C. D. (1994) Non-random acetylation of histone H4 by a cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase as determined by novel methodology. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18576–18582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. An W., and Roeder R. G. (2003) Direct association of p300 with unmodified H3 and H4 N termini modulates p300-dependent acetylation and transcription of nucleosomal templates. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1504–1510 10.1074/jbc.M209355200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chou C. J., Herman D., and Gottesfeld J. M. (2008) Pimelic diphenylamide 106 is a slow, tight-binding inhibitor of class I histone deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35402–35409 10.1074/jbc.M807045200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lauffer B. E., Mintzer R., Fong R., Mukund S., Tam C., Zilberleyb I., Flicke B., Ritscher A., Fedorowicz G., Vallero R., Ortwine D. F., Gunzner J., Modrusan Z., Neumann L., Koth C. M., et al. (2013) Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor kinetic rate constants correlate with cellular histone acetylation but not transcription and cell viability. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26926–26943 10.1074/jbc.M113.490706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schiltz R. L., Mizzen C. A., Vassilev A., Cook R. G., Allis C. D., and Nakatani Y. (1999) Overlapping but distinct patterns of histone acetylation by the human coactivators p300 and PCAF within nucleosomal substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1189–1192 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Grant P. A., Eberharter A., John S., Cook R. G., Turner B. M., and Workman J. L. (1999) Expanded lysine acetylation specificity of Gcn5 in native complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5895–5900 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Urvalek A. M., and Gudas L. J. (2014) Retinoic acid and histone deacetylases regulate epigenetic changes in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19519–19530 10.1074/jbc.M114.556555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gates L. A., Shi J., Rohira A. D., Feng Q., Zhu B., Bedford M. T., Sagum C. A., Jung S. Y., Qin J., Tsai M. J., Tsai S. Y., Li W., Foulds C. E., and O'Malley B. W. (2017) Acetylation on histone H3 lysine 9 mediates a switch from transcription initiation to elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 14456–14472 10.1074/jbc.M117.802074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Imai B. S., Yau P., Baldwin J. P., Ibel K., May R. P., and Bradbury E. M. (1986) Hyperacetylation of core histones does not cause unfolding of nucleosomes. Neutron scatter data accords with disc shape of the nucleosome. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8784–8792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Perry M., and Chalkley R. (1981) The effect of histone hyperacetylation on the nuclease sensitivity and the solubility of chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 3313–3318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Garcia-Ramirez M., Rocchini C., and Ausio J. (1995) Modulation of chromatin folding by histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17923–17928 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Marvin K. W., Yau P., and Bradbury E. M. (1990) Isolation and characterization of acetylated histones H3 and H4 and their assembly into nucleosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 19839–19847 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Jung M., Philpott M., Müller S., Schulze J., Badock V., Eberspächer U., Moosmayer D., Bader B., Schmees N., Fernández-Montalván A., and Haendler B. (2014) Affinity map of bromodomain protein 4 (BRD4) interactions with the histone H4 tail and the small molecule inhibitor JQ1. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 9304–9319 10.1074/jbc.M113.523019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Appikonda S., Thakkar K. N., Shah P. K., Dent S. Y. R., Andersen J. N., and Barton M. C. (2018) Cross-talk between chromatin acetylation and SUMOylation of tripartite motif-containing protein 24 (TRIM24) impacts cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 7476–7485 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Krogan N. J., Dover J., Khorrami S., Greenblatt J. F., Schneider J., Johnston M., and Shilatifard A. (2002) COMPASS, a histone H3 (lysine 4) methyltransferase required for telomeric silencing of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10753–10755 10.1074/jbc.C200023200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tachibana M., Sugimoto K., Fukushima T., and Shinkai Y. (2001) Set domain-containing protein, G9a, is a novel lysine-preferring mammalian histone methyltransferase with hyperactivity and specific selectivity to lysines 9 and 27 of histone H3. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25309–25317 10.1074/jbc.M101914200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Patel A., Dharmarajan V., Vought V. E., and Cosgrove M. S. (2009) On the mechanism of multiple lysine methylation by the human mixed lineage leukemia protein-1 (MLL1) core complex. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24242–24256 10.1074/jbc.M109.014498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nightingale K. P., Gendreizig S., White D. A., Bradbury C., Hollfelder F., and Turner B. M. (2007) Cross-talk between histone modifications in response to histone deacetylase inhibitors: MLL4 links histone H3 acetylation and histone H3K4 methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4408–4416 10.1074/jbc.M606773200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Lomberk G., Mathison A. J., Grzenda A., Seo S., DeMars C. J., Rizvi S., Bonilla-Velez J., Calvo E., Fernandez-Zapico M. E., Iovanna J., Buttar N. S., and Urrutia R. (2012) Sequence-specific recruitment of heterochromatin protein 1 via interaction with Kruppel-like factor 11, a human transcription factor involved in tumor suppression and metabolic diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13026–13039 10.1074/jbc.M112.342634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mizuguchi G., Vassilev A., Tsukiyama T., Nakatani Y., and Wu C. (2001) ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling and histone hyperacetylation synergistically facilitate transcription of chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14773–14783 10.1074/jbc.M100125200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Moritz L. E., and Trievel R. C. (2018) Structure, mechanism, and regulation of polycomb repressive complex 2. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 13805–13814 10.1074/jbc.R117.800367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Gerber M., and Shilatifard A. (2003) Transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II and histone methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26303–26306 10.1074/jbc.R300014200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Coussens N. P., Kales S. C., Henderson M. J., Lee O. W., Horiuchi K. Y., Wang Y., Chen Q., Kuznetsova E., Wu J., Chakka S., Cheff D. M., Cheng K. C., Shinn P., Brimacombe K. R., Shen M., et al. (2018) High-throughput screening with nucleosome substrate identifies small-molecule inhibitors of the human histone lysine methyltransferase NSD2. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 13750–13765 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ali M., Daze K. D., Strongin D. E., Rothbart S. B., Rincon-Arano H., Allen H. F., Li J., Strahl B. D., Hof F., and Kutateladze T. G. (2015) Molecular insights into inhibition of the methylated histone-plant homeodomain complexes by calixarenes. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 22919–22930 10.1074/jbc.M115.669333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Rogakou E. P., Nieves-Neira W., Boon C., Pommier Y., and Bonner W. M. (2000) Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9390–9395 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Burma S., Chen B. P., Murphy M., Kurimasa A., and Chen D. J. (2001) ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42462–42467 10.1074/jbc.C100466200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Goto H., Tomono Y., Ajiro K., Kosako H., Fujita M., Sakurai M., Okawa K., Iwamatsu A., Okigaki T., Takahashi T., and Inagaki M. (1999) Identification of a novel phosphorylation site on histone H3 coupled with mitotic chromosome condensation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25543–25549 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Murnion M. E., Adams R. R., Callister D. M., Allis C. D., Earnshaw W. C., and Swedlow J. R. (2001) Chromatin-associated protein phosphatase 1 regulates aurora-B and histone H3 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26656–26665 10.1074/jbc.M102288200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Brehove M., Wang T., North J., Luo Y., Dreher S. J., Shimko J. C., Ottesen J. J., Luger K., and Poirier M. G. (2015) Histone core phosphorylation regulates DNA accessibility. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 22612–22621 10.1074/jbc.M115.661363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Fong J. J., Nguyen B. L., Bridger R., Medrano E. E., Wells L., Pan S., and Sifers R. N. (2012) β-N-Acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is a novel regulator of mitosis-specific phosphorylations on histone H3. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 12195–12203 10.1074/jbc.M111.315804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Schnell J. D., and Hicke L. (2003) Non-traditional functions of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35857–35860 10.1074/jbc.R300018200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Dover J., Schneider J., Tawiah-Boateng M. A., Wood A., Dean K., Johnston M., and Shilatifard A. (2002) Methylation of histone H3 by COMPASS requires ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28368–28371 10.1074/jbc.C200348200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Dhall A., Wei S., Fierz B., Woodcock C. L., Lee T. H., and Chatterjee C. (2014) Sumoylated human histone H4 prevents chromatin compaction by inhibiting long-range internucleosomal interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 33827–33837 10.1074/jbc.M114.591644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Wu C. (1997) Chromatin remodeling and the control of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28171–28174 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Euskirchen G., Auerbach R. K., and Snyder M. (2012) SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling factors: multiscale analyses and diverse functions. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30897–30905 10.1074/jbc.R111.309302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Chen L., Cai Y., Jin J., Florens L., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., Conaway J. W., and Conaway R. C. (2011) Subunit organization of the human INO80 chromatin remodeling complex: an evolutionarily conserved core complex catalyzes ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11283–11289 10.1074/jbc.M111.222505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. LeRoy G., Loyola A., Lane W. S., and Reinberg D. (2000) Purification and characterization of a human factor that assembles and remodels chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14787–14790 10.1074/jbc.C000093200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Schwanbeck R., Xiao H., and Wu C. (2004) Spatial contacts and nucleosome step movements induced by the NURF chromatin remodeling complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39933–39941 10.1074/jbc.M406060200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Korber P., Barbaric S., Luckenbach T., Schmid A., Schermer U. J., Blaschke D., and Hörz W. (2006) The histone chaperone Asf1 increases the rate of histone eviction at the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5539–5545 10.1074/jbc.M513340200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Altaf M., Auger A., Monnet-Saksouk J., Brodeur J., Piquet S., Cramet M., Bouchard N., Lacoste N., Utley R. T., Gaudreau L., and Côté J. (2010) NuA4-dependent acetylation of nucleosomal histones H4 and H2A directly stimulates incorporation of H2A.Z by the SWR1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15966–15977 10.1074/jbc.M110.117069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Abbott D. W., Ivanova V. S., Wang X., Bonner W. M., and Ausió J. (2001) Characterization of the stability and folding of H2A.Z chromatin particles: implications for transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41945–41949 10.1074/jbc.M108217200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. McCullough L. L., Connell Z., Xin H., Studitsky V. M., Feofanov A. V., Valieva M. E., and Formosa T. (2018) Functional roles of the DNA-binding HMGB domain in the histone chaperone FACT in nucleosome reorganization. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 6121–6133 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Pazin M. J., Hermann J. W., and Kadonaga J. T. (1998) Promoter structure and transcriptional activation with chromatin templates assembled in vitro. A single Gal4-VP16 dimer binds to chromatin or to DNA with comparable affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34653–34660 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Jiang W., Nordeen S. K., and Kadonaga J. T. (2000) Transcriptional analysis of chromatin assembled with purified ACF and dNAP1 reveals that acetyl-CoA is required for preinitiation complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39819–39822 10.1074/jbc.C000713200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Szerlong H. J., Prenni J. E., Nyborg J. K., and Hansen J. C. (2010) Activator-dependent p300 acetylation of chromatin in vitro: enhancement of transcription by disruption of repressive nucleosome-nucleosome interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31954–31964 10.1074/jbc.M110.148718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Khuong M. T., Fei J., Cruz-Becerra G., and Kadonaga J. T. (2017) A simple and versatile system for the ATP-dependent assembly of chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 19478–19490 10.1074/jbc.M117.815365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]