Abstract

In honor of the 100th birthday of Dr. Herbert Tabor, JBC's Editor-in-Chief for 40 years, I will review here JBC's extensive coverage of the field of cytochrome P450 (P450) research. Research on the reactions catalyzed by these enzymes was published in JBC before it was even realized that they were P450s, i.e. they have a “pigment” with an absorption maximum at 450 nm. After the P450 pigment discovery, reported in JBC in 1962, the journal proceeded to publish the methods for measuring P450 activities and many seminal findings. Since then, the P450 field has grown extensively, with significant progress in characterizing these enzymes, including structural features, catalytic mechanisms, regulation, and many other aspects of P450 biochemistry. JBC has been the most influential journal in the P450 field. As with many other research areas, Dr. Tabor deserves a great deal of the credit for significantly advancing this burgeoning and important topic of research.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, steroid, eicosanoid, retinoid, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria

Introduction

It is a pleasure to contribute this article on the occasion of Dr. Herbert Tabor's 100th birthday. I have indeed counted it as a special privilege to work with him for a number of years at The Journal of Biological Chemistry. His leadership at JBC has benefited many research communities, including that of cytochrome P450 (P450), a field that I have worked in since 1973. I have tried to highlight some of the more seminal advances in the P450 field that were published in JBC. In my opinion, P450 is a classic example of how good biochemistry moved a field to its current place, with all of the translational applications it now has.

With limitation of space and number of references, it is impossible to mention all of the P450 research published in JBC. A Clarivate “topic” search yielded 1437 “P450” or “P-450” papers in JBC, but many were probably missed if they did not actually use this term. In 2009, a Special Meeting Collection on P450 was done, and it includes 63 “classic” JBC papers published since 1962 (available at http://www.jbc.org/site/collections/p450/classics/60s70s.xhtml). In addition to a number of Minireviews on P450, the reader is also referred to several Classics and Reflections (1–7) and a Thematic Series that appeared in 2013 (8). I apologize for not being able to include more papers and authors, but we have had a historic limit of ∼100 for JBC Minireviews, the model for this Collection. There is no question that JBC has been the single most influential journal in P450 research.

Early work and the discovery of P450

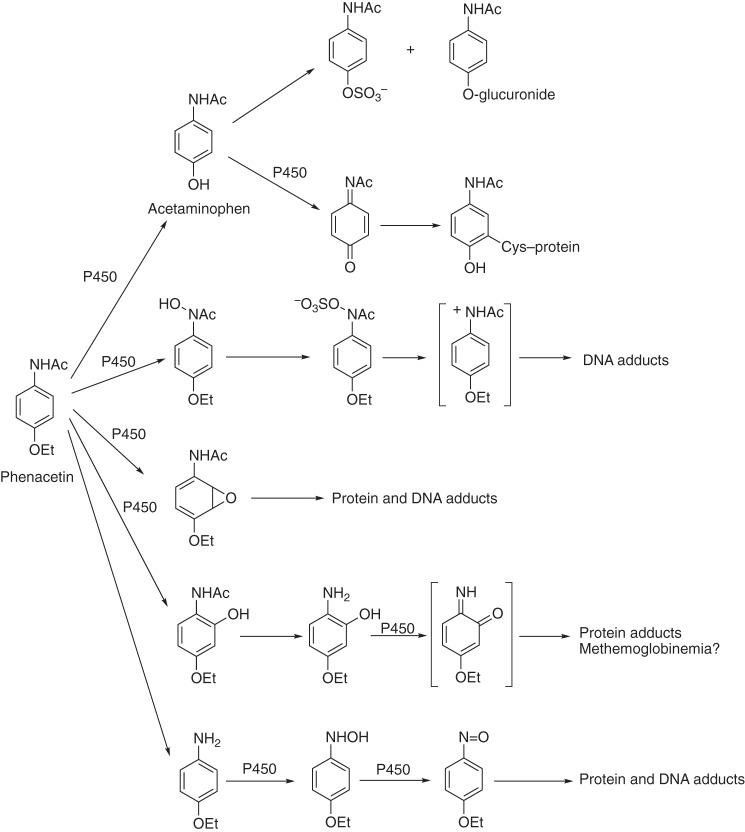

P450 research was published in JBC before anyone realized it was P450. The field had its roots in the studies of the metabolism of drugs (9), steroids (10, 11), and chemical carcinogens (Fig. 1) (12, 13). These studies were done when pyridine nucleotide–dependent activation of molecular oxygen (O2) was a new concept (16).

Figure 1.

Roles of P450s in the bioactivation and detoxication of chemicals: The complex example of phenacetin. Acetaminophen (paracetamol, Tylenol®) is widely used as an analgesic, safe at low doses and hepatotoxic at high levels (15). Phenacetin has been classified as a carcinogen and withdrawn from use. Only in a few cases are the structures of the protein and DNA adducts known. Some of the indicated P450s have been identified in different species, including humans (14, 15).

The term “P450” was used to describe a “pigment” with an absorption maximum at 450 nm seen with the ferrous–carbon monoxide complex of P450 in rat liver microsomes, published in JBC in 1962 (17). Tsuneo Omura and Ryo Sato published two more classic papers in 1964 (1, 18, 19), the first of which describes the spectrophotometric assay of P450 still ubiquitously used today.

An independent line of investigation by Irwin Gunsalus on a bacterial system that oxidized camphor also led to a P450, termed P450cam (now named P450 101A1) (2, 20, 21). Because of its soluble nature and ease of large-scale purification, P450cam has served as a very useful model in structural and biophysical studies for many years (22–24).

The mammalian P450s are all membrane-bound (mostly in the endoplasmic reticulum, some in mitochondria) and were difficult to work with in the 1960s. However, Minor Coon and Anthony Lu were able to use detergents and glycerol to successfully separate the P450, NADPH-P450 reductase, and phospholipid components from rabbit liver microsomes and then reconstitute fatty acid ω-hydroxylation activity by recombining the three components. Two classic papers published in 1968 and 1969 reported these milestones (3, 25, 26).

Purification of mammalian P450s

In today's world of recombinant heterologous expression systems and artificial affinity tags, it is sometimes hard to convey to students the difficulties of (i) purifying enzymes from tissues and (ii) evaluating criteria to determine whether a purified protein is homogeneous. However, there were several notable successes of purification of P450s from rabbit and rat liver microsomes in the 1970s (27–30). The significance of these purifications should be appreciated, because work beginning in the 1960s suggested that there were at least two forms of P450 in liver microsomes, although this proposal was not accepted by all. The 1970s saw a shift to biochemistry as a means of answering many of the fundamental questions about P450s. Indeed, proposals that there were as many as four or five P450s were met with skepticism. Today, we know, from genomic analysis, that there are 57 human P450 genes plus 88 in rats and 103 in mice.

Other important developments involved the accessory flavoprotein, NADPH-P450 reductase. One JBC paper by Bettie Sue Masters described an affinity column–based purification (31), still used today in my own laboratory. Another pair of papers by Janice Vermilion, working with Minor Coon and Vincent Massey, characterized electron flow through NADPH-P450 reductase (32, 33) and it is still generally accepted following more work by others.

Mitochondrial and microsomal P450s involved in steroid metabolism, including bile acids

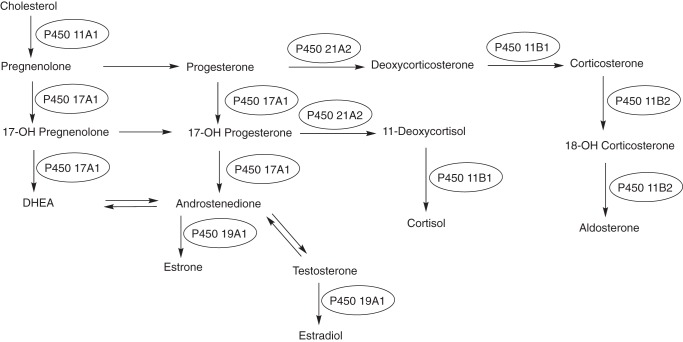

Most of the mammalian work described thus far was with the microsomal P450s (now known to be 50 of the 57 human P450s). However, it was already recognized that several important steroid oxidations occur in mitochondria, including those catalyzed by the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (now known as P450 11A1), which begins the whole process of steroidogenesis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

P450s involved in steroid metabolism. The pathways are dominated by P450s, with the only other major players being dehydrogenases.

The (seven) mitochondrial P450s are synthesized on ribosomes and then enter mitochondria following proteolytic processing. Instead of the microsomal NADPH-P450 reductase, these P450s receive electrons from a mitochondrial electron transport system consisting of a flavoprotein and a ferredoxin, NADPH-adrenodoxin reductase and adrenodoxin, respectively. Seminal early contributions toward understanding these systems were made by the groups of David Cooper, Ronald Estabrook, Otto Rosenthal, Michael Waterman, Henry Kamin, Peter Hall, and others (34–37). Other work by Narayan Avadhani has shown that fractions of some microsomal P450s are also partially localized in mitochondria (38) due to processing and other phenomena. I would be remiss not to mention the seminal work that David Russell (a former JBC Associate Editor) did by applying techniques of recombinant DNA technology to solving problems with several P450s involved in the metabolism of sterols and vitamins (39–41). A number of other seminal papers in this area were published in JBC (42–51).

Human P450s

Experimental animals are used extensively in many areas of research, including drug discovery and development. In our early work with rabbit and rat liver P450s, we (and others) noted a number of differences, and we realized that ultimately the biochemistry of the human P450s would have to be studied directly in order to understand them. However, obtaining human tissue samples needed for purification and other studies was not easy.

Important observations about the influence of genetic variation by Robert Smith led me to the view that a single P450 could have a dominant role in the metabolism of a drug and that using such assays could guide productive purification. In the 1980s, we were successful in purifying what we now recognize to be several of the major human P450s (4, 14, 52, 53); other laboratories also contributed (54). One could argue that this work would have been done eventually by cloning and recombinant expression studies, but this early work shaped several concepts and was applied in the pharmaceutical industry. For instance, a limited number of P450s (∼5) dominate drug metabolism. Induction and inhibition of these are major issues in drug–drug interactions. Genetic deficiencies are important. Today, it is possible to use in vitro methods to predict not only drug clearance for new compounds but also drug–drug interactions, pharmacogenetic issues, and other drug effects before proceeding with clinical trials; attrition of drug candidates due to human pharmacokinetic problems is no longer the major issue.

Metabolism of vitamins and eicosanoids

Although much of the interest in P450 came from studies on drugs, steroids, and carcinogens, these enzymes make major contributions in the metabolism of a number of other physiological compounds. Hector DeLuca had demonstrated that P450-catalyzed hydroxylation of vitamin D3 was important in generating the most active forms (49, 50), and subsequent work has shown the importance of several P450s in the activation and catabolism of vitamin D (55–57). Deficiency in P450 27B1 is a cause of rickets disease (58, 59).

Retinoid metabolism involves several P450s, and maintaining the appropriate balance of proper levels of the signal retinoic acid is important. Several P450s oxidize retinoic acid (60, 61). More recent work from our own laboratory (in collaboration with Joseph Corbo) has shown the role of P450 27C1-catalyzed 3,4-desaturation of retinol in the eye of fish and amphibians, adjusting their visual spectra; however, in humans it is a skin enzyme (62) whose desaturation function is not yet known.

Prostaglandin H2 is converted to thromboxane and prostacyclin by two P450s (5A1 and 8A1), as shown by Volker Ullrich and co-workers (63, 64). These are unusual P450 reactions in that they do not need electrons or O2; they rearrange the endoperoxide function of prostaglandin H2 (65). The balance between their two reactions has important health consequences in several disease contexts. Leukotrienes are also substrates for P450 hydroxylation (66).

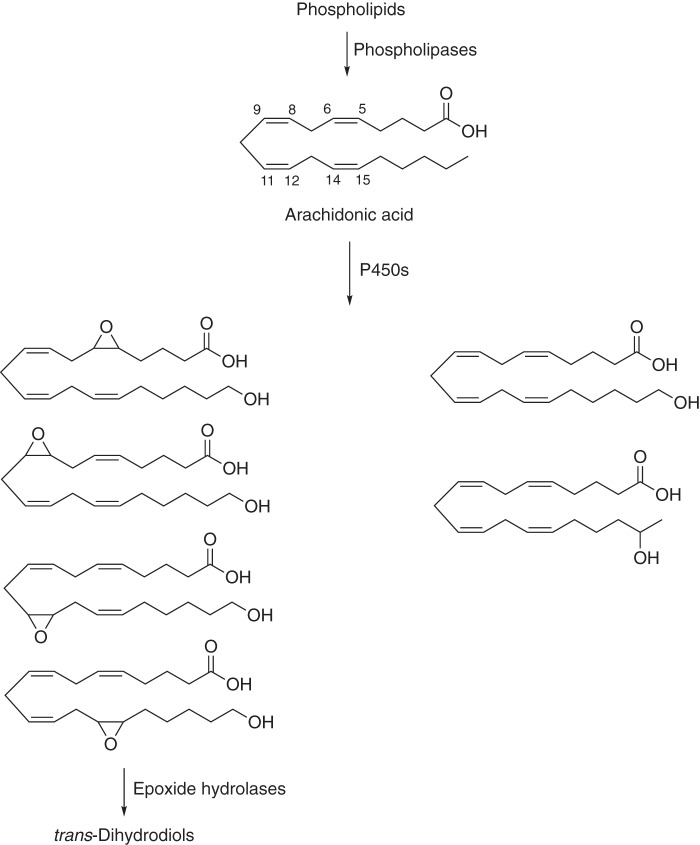

Even some simple oxidation products of arachidonic acid have surprisingly potent biological activities (Fig. 3), as reported in a number of papers published in JBC by Jorge Capdevila and others (67–72). The epoxides and ω-hydroxy products of arachidonic acid have vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive activities, respectively, and are being considered in the context of cardiovascular and renal diseases.

Figure 3.

Oxidations of arachidonic acid catalyzed by P450s (67–72). The four epoxides (epoxytrienoic acids or EETs) are formed primarily by P450 Family 2C and 2J enzymes, and the ω-hydroxylation product (20-hydroxyeicosatetrenoic acid or 20-HETE) is formed primarily by human Family 4A and 4F enzymes. The epoxides have roles as vasodilators. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetrenoic acid can exert both pro-hypertensive (vasoconstriction) and anti-hypertensive (natriuresis) effects, depending on its site of synthesis.

Catalytic mechanisms of P450 catalysis

A number of the most important publications in this area have appeared in JBC. Paul Hollenberg and Lowell Hager's discovery (73) that chloroperoxidase is spectrally like P450s was a major driver in terms of “Compound I” chemistry, which was originally described in peroxidases and is now widely accepted in the P450 field. Paul Ortiz de Montellano and associates demonstrated the 1-electron oxidation of amines (74). Other important papers in a variety of areas include many kinetic and other mechanistic studies (23, 24, 75–77).

Regulation of P450s

The development of recombinant DNA methods in the 1980s greatly facilitated the study of the regulation of P450 genes, as with all other systems, and many of the pioneering studies were published in JBC. Although demonstrating enhanced mRNA transcription, isolating cDNAs, and obtaining nucleotide sequences (on home-made gels!) may seem trivial today, it was not 30 years ago. Many of the studies on both P450s involved in the metabolism of both drugs and endogenous compounds were first published in JBC (78–85). Some of the first complete nucleotide sequences of cDNAs encoding P450s (an important milestone at the time) were first published by Yoshiaki Fujii-Kuriyama in JBC (86, 87). It is also noteworthy that the seminal papers by Alan Poland and Christopher Bradfield on the biochemistry of the Ah receptor were published in JBC (88–90).

P450 structure and function

The first P450 X-ray crystal structure was of bacterial P450cam (91). For several years, this was the only P450 structure available. An early effort at modeling, based on this structure, was made by Osamu Gotoh (92) in a JBC paper. The model has actually proven to have held up well.

One of the challenges in P450 research had been the ability to achieve high yields of heterologously expressed proteins. Work in 1991 from the laboratories of Minor Coon (93) and John Chiang (94) showed that expression of active enzymes was possible in Escherichia coli. The 1990s saw the publication of many site-directed mutagenesis studies on P450s in JBC, which are too numerous to discuss (95, 96).

The membrane-bound P450s had been difficult to crystallize, and work at the turn of the millennium by Eric Johnson paved the way. Many of these structures were published in JBC (97, 98), and JBC has been a leader in demanding rigor for crystal structures (i.e. Protein Data Bank validation requirements). A recent count in the Protein Data Bank showed at least 850 P450 X-ray crystal structures, 179 of which are human P450s. JBC continues to publish many P450 structures. At this time, crystal structures of 21 of the 57 human P450s have been reported, plus two animal orthologs. Several of these structures have revealed important mechanistic inferences, e.g. the recent work of Eric Johnson and Allan Rettie on P450 4B1 (99).

More microbial P450s

P450cam was the first but by no means the last bacterial P450 of interest. Armand Fulco's work on P450BM-3 (now termed P450 102A1) was first published in JBC (100). P450BM-3 was the second P450 X-ray structure to be determined and became a popular platform for biotechnology applications.

Microbial P450s are not only useful models but have important metabolic roles (e.g. in antibiotic synthesis) and are also drug targets in some diseases (e.g. tuberculosis). A few of the many microbial P450 papers in JBC include studies on the enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (101, 102), Streptomyces coelicolor (103), and Candida albicans (104).

Plant P450s

Plants have far more P450-encoding genes than mammals, and Arabidopsis thaliana has 249 and wheat has 1476 (drnelson.uthsc.edu/cytochromeP450.html). Plant P450s are configured in complex metabolic pathways, and a number of studies on plant P450s have been published in JBC (105, 106).

P450s and disease

With more knowledge about P450s, there is now an enhanced appreciation of their contributions to disease (59). The role of P450 2E1, an ethanol-inducible enzyme, in acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity was convincingly demonstrated by Frank Gonzalez in a transgenic mouse model (Fig. 1) (15). The molecular basis for deficiencies of several P450s has been demonstrated in several inherited diseases, particularly in endocrine dysfunction (107, 108). JBC has also published many of the studies on the relationship of arachidonic acid oxidation products and hypertension (Fig. 3) (67–71), including a transgenic mouse study demonstrating a role for P450 4A11 (72). Interesting transgenic models with P450s having potential implications in understanding other human diseases have also been published in JBC (109, 110).

Relevance of P450 research

Today, the P450 field can be considered to be mature. That does not mean that all questions have been answered. However, 56 years after the “discovery” of this protein superfamily (17), it is reasonable to ask what benefits have accrued from the investment in its study. Indeed, there have been many practical outcomes, mainly in human medicine but now also in other areas.

We now understand the molecular basis of many diseases, perhaps most notably in endocrine diseases (59). For instance, many clinical cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia are now understood to result from amino acid substitutions in the CYP21A2 gene (108).

Knowledge about the human P450s involved in drug metabolism has led to the rapid characterization of substrates, inhibitors, and inducers with new drug candidates and has enabled rapid in vitro prediction of human (in vivo) pharmacokinetics and drug–drug interactions. Concepts developed from our knowledge of human P450s have led to better design by medicinal chemists, directing chemical synthesis to avoid rapid metabolism and bioactivation to toxic products (15). In the realm of drug development, it is now possible to understand metabolism and sometimes the toxicity of drugs in animal models through their interactions with P450s, in terms of similarities and differences with human models. Furthermore, it is possible to avoid many issues with genetic polymorphisms in drug metabolism and extreme pharmacokinetic variations. Moreover, potential inhibitors (e.g. drugs such as ritonavir for P450 3A4) can be managed effectively.

Future research needs for the P450 field

Basic research

Every aspect of basic P450 research would benefit from deeper knowledge. The following list is driven in part by some of my own interests and is not intended to be comprehensive.

One area of need is more information about the “orphan” P450s, not only in plants and microorganisms (i.e. comprising most P450s) but also humans. There are true orphans (e.g. P450 20A1), about which almost nothing is known, and also the “xenobiotic-metabolizing” enzymes. Is the role of the xenobiotic-metabolizing P450s (e.g. human P450 Families 1–3) limited to protection from foreign chemicals, or are their demonstrated interactions with endogenous substrates (e.g. fatty acids, steroids) relevant?

We have more to learn about three-dimensional structures and their relationships to P450 function. Currently, 21 of the human P450s have structures in addition to two animal orthologs (4B1 and 24A1). This leaves 36 human P450s that need structural characterization.

Although much has been written about allosteric regulation, we have few details beyond some X-ray crystal structures with multiple ligands bound. The matter of the auxiliary accessory protein cytochrome b5 is still devoid of many details. There are only two crystal structures of P450s with auxiliary partners (ferredoxins) but none for microsomal P450s with NADPH-P450 reductase or cytochrome b5.

Finally, are we finished with learning about the chemistry or is there more to learn? Are there really alternatives to the Compound I mechanism or not? There are also kinetic questions about the degree of processivity of multistep P450 oxidations (111), and there is very limited information about the kinetics of individual steps in the reactions involving the mitochondrial P450s (62, 112).

Applied research

Although we have a considerable amount of structural information about P450s (at least 850 Protein Data Bank entries, including 179 for humans), the question can be raised as to how we can better use it. For instance, can we really understand inherited P450 deficiencies seen in the clinic at a molecular level? Are WT structures really that predictive of problems due to a single base change (108, 113)?

Chemical carcinogenesis had long been a driver in the P450 field, but now we need to learn more about the roles of P450s (and their variants) in diseases, particularly nonendocrine diseases. What does the association between P450 4A11 variants and hypertension mean (114)? What are the prospects for gaining more insight into the association between P450 differences in humans and the incidence of certain cancers?

Although we have a large and developing database on single nucleotide variations (SNVs) in P450s, are we really getting any closer to applying it in clinical practice? Despite the excitement 20 years ago, can P450 research drive “personalized medicine” more than in a few cases as with P450s 2C9 and 2D6 (e.g. warfarin and iloperidone)?

Lastly, there are new research applications that are not discussed above such as the targeting of human P450s with drugs. For instance, inhibition of P450 19A1, the steroid aromatase, is now a popular strategy for treating breast cancer, and research is in progress to inhibit several other P450s in diseases, e.g. P450s 11B2, and 17A1. Another area of opportunity is to target fungal and bacterial P450s that are critical to membrane synthesis and viability (101, 102, 104, 115).

Finally, there are many opportunities for practical applications of P450 knowledge to veterinary and agricultural problems. Many of the applications described in human medicine can also be applied in the veterinary arena. There is great unrealized opportunity for understanding the plant P450s and their interactions with the P450s in insects and other plants. This information can in turn be used for the effective application of genetic modifications and pesticides in agriculture.

My role at JBC and relationship with Dr. Tabor

I began doing research on P450s in 1973, as a postdoctoral fellow with Minor Coon at the University of Michigan. In 1975, I started my own laboratory as a Biochemistry Faculty Member at Vanderbilt University. I have continued working with P450 since then, which means that I have spent 45 years in the field. My first P450 paper was published in JBC in 1975, and I have continued to publish much of my own research in the journal. By my count, I have authored or co-authored 117 primary articles in JBC (not all on P450), plus a number of reviews, and JBC remains a favorite journal for our papers.

In 1984, I was asked to join the JBC Editorial Board. When I was in the middle of my fourth term, I was invited to become an Associate Editor in 2006. Since that time, I have worked with Herb Tabor in several aspects of JBC work, and I have come to truly admire him as a person and appreciate what he has done for JBC (Fig. 4). Herb Tabor was Editor-in-Chief for 40 years. After I served in that capacity for 1 year (2015–2016) I can better appreciate all that he did, particularly in the pre-electronic era when paper manuscripts arrived at his home doorstep every evening for assignment. I also understand the effort required in dealing with problem manuscripts, author complaints, and the other issues that come with the job. Herb Tabor managed JBC very effectively during his long tenure as Editor-in-Chief, allowing Associate Editors to drive the journal activities and making critical decisions based on their input. He also reviewed manuscripts himself and has a genuine appreciation of what Associate Editors and Editorial Board Members do.

Figure 4.

Dr. Herbert Tabor (left) and the author at lunch at Dr. Tabor's home in 2016.

Dr. Tabor is an amazing man—he graduated from Harvard University at the age of 18 and from Harvard Medical School at 22. To this day he still assigns some of the new manuscripts and has gladly filled in when I am unavailable for this task. He is really a brilliant man but is also one of the most humble people I know. His focus was always on what was good for JBC and what was good for science, not for himself.

I rank being able to interact with Herb Tabor among the true privileges of my career. It has been a pleasure to work with him. I wish there were more people like Herb Tabor in science, but I think we can all benefit from trying to emulate him.

Finally, Herb, I wish you all the best on this occasion of your 100th birthday. Thanks for the things you taught me about being an editor and a person.

Acknowledgments

I thank Prof. Michael Waterman for reviewing this article and adding some historical points. I also thank my long-time helper and JBC Editorial Assistant Kathy Trisler for her assistance in preparing the article and Barbara Gordon for the photograph (Fig. 4). Finally, I thank the many individual scientists in the P450 field who have served on the JBC Editorial Board over the years. Without their efforts, none of this would be possible.

Footnotes

This JBC Review is part of a collection honoring Herbert Tabor on the occasion of his 100th birthday. The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- 1. Kresge N., Simoni R. D., and Hill R. L. (2006) The characterization of cytochrome P-450 by Ryo Sato. J. Biol. Chem. 281, e15 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kresge N., Simoni R. D., and Hill R. L. (2007) Classics: The bacterial cytochrome P-450 and Irwin C. Gunsalus. J. Biol. Chem. 282, e4–e5 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kresge N., Simoni R. D., and Hill R. L. (2006) The purification of cytochrome P-450 and its isozymes: The work of Minor J. Coon. J. Biol. Chem. 281, e38 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mukhopadhyay R. (2012) Human cytochrome P450s: the work of Frederick Peter Guengerich. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15798–15800 10.1074/jbc.O112.000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coon M. J. (2002) Enzyme ingenuity in biological oxidations: a trail leading to cytochrome P450. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28351–28363 10.1074/jbc.R200015200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Masters B. S. S. (2009) A professional and personal odyssey. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19765–19780 10.1074/jbc.X109.007518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2015) Heme and I. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 21833–21844 10.1074/jbc.X115.680066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guengerich F. P. (2013) New trends in cytochrome P450 research at the half-century mark. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17063–17064 10.1074/jbc.R113.466821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Axelrod J. (1955) The enzymatic deamination of amphetamine. J. Biol. Chem. 214, 753–763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan K. J. (1959) Biological aromatization of steroids. J. Biol. Chem. 234, 268–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson E. A. Jr., and Siiteri P. K. (1974) The involvement of human placental microsomal cytochrome P-450 in aromatization. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 5373–5378 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mueller G. C., and Miller J. A. (1948) The metabolism of 4-dimethylaminoazobenzene by rat liver homogenates. J. Biol. Chem. 176, 535–544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown R. R., Miller J. A., and Miller E. C. (1954) The metabolism of methylated aminoazo dyes. IV. Dietary factors enhancing demethylation in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 209, 211–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Distlerath L. M., Reilly P. E., Martin M. V., Davis G. G., Wilkinson G. R., and Guengerich F. P. (1985) Purification and characterization of the human liver cytochromes P-450 involved in debrisoquine 4-hydroxylation and phenacetin O-deethylation, two prototypes for genetic polymorphism in oxidative drug metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 9057–9067 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee S. S., Buters J. T., Pineau T., Fernandez-Salguero P., and Gonzalez F. J. (1996) Role of CYP2E1 in the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12063–12067 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mason H. S. (1957) Mechanisms of oxygen metabolism. Science 125, 1185–1188 10.1126/science.125.3259.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Omura T., and Sato R. (1962) A new cytochrome in liver microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 237, 1375–1376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Omura T., and Sato R. (1964) The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. I. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J. Biol. Chem. 239, 2370–2378 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Omura T., and Sato R. (1964) The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. II. Solubilization, purification, and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 239, 2379–2385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hedegaard J., and Gunsalus I. C. (1965) Mixed function oxidation. IV. An induced methylene hydroxylase in camphor oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 240, 4038–4043 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katagiri M., Ganguli B. N., and Gunsalus I. C. (1968) A soluble cytochrome P450 functional in methylene hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 3543–3546 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tyson C. A., Lipscomb J. D., and Gunsalus I. C. (1972) The roles of putidaredoxin and P450cam in methylene hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 5777–5784 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lipscomb J. D., Sligar S. G., Namtvedt M. J., and Gunsalus I. C. (1976) Autooxidation and hydroxylation reactions of oxygenated cytochrome P-450cam. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1116–1124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brewer C. B., and Peterson J. A. (1988) Single turnover kinetics of the reaction between oxycytochrome P-450cam and reduced putidaredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 791–798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu A. Y., and Coon M. J. (1968) Role of hemoprotein P-450 in fatty acid ω-hydroxylation in a soluble enzyme system from liver microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 1331–1332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu A. Y., Junk K. W., and Coon M. J. (1969) Resolution of the cytochrome P-450-containing ω-hydroxylation system of liver microsomes into three components. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 3714–3721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haugen D. A., van der Hoeven T. A., and Coon M. J. (1975) Purified liver microsomal cytochrome P-450: separation and characterization of multiple forms. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 3567–3570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu A. Y., Kuntzman R., West S., Jacobson M., and Conney A. H. (1972) Reconstituted liver microsomal enzyme system that hydroxylates drugs, other foreign compounds, and endogenous substrates: II. Role of the cytochrome P-450 and P-448 fractions in drug and steroid hydroxylations. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 1727–1734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ryan D., Lu A. Y., West S., and Levin W. (1975) Multiple forms of cytochrome P-450 in phenobarbital- and 3-methylcholanthrene-treated rats. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 2157–2163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guengerich F. P. (1978) Separation and purification of multiple forms of microsomal cytochrome P-450. Partial characterization of three apparently homogeneous cytochromes P-450 prepared from livers of phenobarbital- and 3-methylcholanthrene-treated rats. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 7931–7939 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yasukochi Y., and Masters B. S. S. (1976) Some properties of a detergent-solubilized NADPH-cytochrome c (cytochrome P-450) reductase purified by biospecific affinity chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 5337–5344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vermilion J. L., and Coon M. J. (1978) Purified liver microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase: spectral characterization of oxidation-reduction states. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 2694–2704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vermilion J. L., Ballou D. P., Massey V., and Coon M. J. (1981) Separate roles for FMN and FAD in catalysis by liver microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 266–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cooper D. Y., Estabrook R. W., and Rosenthal O. (1963) The stoichiometry of C21 hydroxylation of steroids by adrenocortical microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 1320–1323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schleyer H., Cooper D. Y., and Rosenthal O. (1972) Preparation of the heme protein P-450 from the adrenal cortex and some of its properties. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 6103–6110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lambeth J. D., Kitchen S. E., Farooqui A. A., Tuckey R., and Kamin H. (1982) Cytochrome P-450scc-substrate interactions: studies of binding and catalytic activity using hydroxycholesterols. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 1876–1884 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DuBois R. N., Simpson E. R., Kramer R. E., and Waterman M. R. (1981) Induction of synthesis of cholesterol side chain cleavage cytochrome P-450 by adrenocorticotropin in cultured bovine adrenocortical cells. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 7000–7005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Niranjan B. G., Wilson N. M., Jefcoate C. R., and Avadhani N. G. (1984) Hepatic mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 system: distinctive features of cytochrome P-450 involved in the activation of aflatoxin B1 and benzo(a)pyrene. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 12495–12501 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jelinek D. F., Andersson S., Slaughter C. A., and Russell D. W. (1990) Cloning and regulation of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in bile acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 8190–8197 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cali J. J., and Russell D. W. (1991) Characterization of human sterol 27-hydroxylase: a mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 that catalyzes multiple oxidation reactions in bile acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 7774–7778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cheng J. B., Motola D. L., Mangelsdorf D. J., and Russell D. W. (2003) De-orphanization of cytochrome P450 2R1: a microsomal vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38084–38093 10.1074/jbc.M307028200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Momoi K., Okamoto M., Fujii S., Kim C. Y., Miyake Y., and Yamano T. (1983) 19-Hydroxylation of 18-hydroxy-11-deoxycorticosterone catalyzed by cytochrome P-45011β of bovine adrenocortex. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 8855–8860 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chu J.-W., and Kimura T. (1973) Studies on adrenal steroid hydroxylases: molecular and catalytic properties of adrenodoxin reductase (a flavoprotein). J. Biol. Chem. 248, 2089–2094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Matocha M. F., and Waterman M. R. (1984) Discriminatory processing of the precursor forms of cytochrome P-450scc and adrenodoxin by adrenocortical and heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 8672–8678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kashiwagi K., Dafeldecker W. P., and Salhanick H. A. (1980) Purification and characterization of mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 associated with cholesterol side chain cleavage from bovine corpus luteum. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 2606–2611 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shikita M., and Hall P. F. (1973) Cytochrome P-450 from bovine adrenocortical mitochondria: An enzyme for the side chain cleavage of cholesterol: I. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 248, 5598–5604 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bryson M. J., and Sweat M. L. (1968) Cleavage of cholesterol side chain associated with cytochrome P-450, flavoprotein, and nonheme iron-protein derived from the bovine adrenal cortex. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 2799–2804 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Björkhem I., Holmberg I., Oftebro H., and Pedersen J. I. (1980) Properties of a reconstituted vitamin D3 25-hydroxylase from rat liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 5244–5249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ghazarian J. G., Jefcoate C. R., Knutson J. C., Orme-Johnson W. H., and DeLuca H. F. (1974) Mitochondrial cytochrome P450. A component of chick kidney 25-hydrocholecalciferol-1α-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 3026–3033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gray R. W., Omdahl J. L., Ghazarian J. G., and DeLuca H. F. (1972) 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol-1-hydroxylase. Subcellular location and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 7528–7532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mornet E., Dupont J., Vitek A., and White P. C. (1989) Characterization of two genes encoding human steroid 11β-hydroxylase (P-45011β). J. Biol. Chem. 264, 20961–20967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shimada T., Misono K. S., and Guengerich F. P. (1986) Human liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 mephenytoin 4-hydroxylase, a prototype of genetic polymorphism in oxidative drug metabolism. Purification and characterization of two similar forms involved in the reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 909–921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guengerich F. P., Martin M. V., Beaune P. H., Kremers P., Wolff T., and Waxman D. J. (1986) Characterization of rat and human liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 forms involved in nifedipine oxidation, a prototype for genetic polymorphism in oxidative drug metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 5051–5060 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gut J., Catin T., Dayer P., Kronbach T., Zanger U., and Meyer U. A. (1986) Debrisoquine/sparteine-type polymorphism of drug oxidation: purification and characterization of two functionally different human liver cytochrome P-450 isozymes involved in impaired hydroxylation of the prototype substrate bufuralol. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 11734–11743 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Andersson S., Holmberg I., and Wikvall K. (1983) 25-Hydroxylation of C27-steroids and vitamin D3 by a constitutive cytochrome P-450 from rat liver microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 6777–6781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pedersen J. I., Shobaki H. H., Holmberg I., Bergseth S., and Björkhem I. (1983) 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase in rat kidney mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 742–746 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Masumoto O., Ohyama Y., and Okuda K. (1988) Purification and characterization of vitamin D 25-hydroxylase from rat liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 14256–14260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kitanaka S., Takeyama K., Murayama A., Sato T., Okumura K., Nogami M., Hasegawa Y., Niimi H., Yanagisawa J., Tanaka T., and Kato S. (1998) Inactivating mutations in the 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-hydroxylase gene in patients with pseudovitamin D-deficiency rickets. New Engl. J. Med. 338, 653–661 10.1056/NEJM199803053381004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nebert D. W., and Russell D. W. (2002) Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet 360, 1155–1162 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11203-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. White J. A., Guo Y. D., Baetz K., Beckett-Jones B., Bonasoro J., Hsu K. E., Dilworth F. J., Jones G., and Petkovich M. (1996) Identification of the retinoic acid-inducible all-trans-retinoic acid 4-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 29922–29927 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Taimi M., Helvig C., Wisniewski J., Ramshaw H., White J., Amad M., Korczak B., and Petkovich M. (2004) A novel human cytochrome P450, CYP26C1, involved in metabolism of 9-cis and all-trans isomers of retinoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 77–85 10.1074/jbc.M308337200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Johnson K. M., Phan T. T. N., Albertolle M. E., and Guengerich F. P. (2017) Human mitochondrial cytochrome P450 27C1 is localized in skin and preferentially desaturates trans-retinol to 3,4-dehydroretinol. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 13672–13687 10.1074/jbc.M116.773937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Haurand M., and Ullrich V. (1985) Isolation and characterization of thromboxane synthase from human platelets as a cytochrome P-450 enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 15059–15067 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hara S., Miyata A., Yokoyama C., Inoue H., Brugger R., Lottspeich F., Ullrich V., and Tanabe T. (1994) Isolation and molecular cloning of prostacyclin synthase from bovine endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19897–19903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hecker M., and Ullrich V. (1989) On the mechanism of prostacyclin and thromboxane A2 biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 141–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Soberman R. J., Okita R. T., Fitzsimmons B., Rokach J., Spur B., and Austen K. F. (1987) Stereochemical requirements for substrate specificity of LTB4 20-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 12421–12427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Capdevila J. H., Karara A., Waxman D. J., Martin M. V., Falck J. R., and Guengerich F. P. (1990) Cytochrome P-450 isoenzyme control of the regio- and enantiofacial selectivity of microsomal arachidonic acid epoxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10865–10871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Capdevila J. H., Wei S., Yan J., Karara A., Jacobson H. R., Falck J. R., Guengerich F. P., and DuBois R. N. (1992) Cytochrome P-450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase. Regulatory control of the renal epoxygenase by dietary salt loading. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 21720–21726 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wu S., Moomaw C. R., Tomer K. B., Falck J. R., and Zeldin D. C. (1996) Molecular cloning and expression of CYP2J2, a human cytochrome P450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase highly expressed in heart. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 3460–3468 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lasker J. M., Chen W. B., Wolf I., Bloswick B. P., Wilson P. D., and Powell P. K. (2000) Formation of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, a vasoactive and natriuretic eicosanoid, in human kidney. Role of CYP4F2 and CYP4A11. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4118–4126 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zeldin D. C. (2001) Epoxygenase pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36059–36062 10.1074/jbc.R100030200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Savas Ü., Wei S., Hsu M. H., Falck J. R., Guengerich F. P., Capdevila J. H., and Johnson E. F. (2016) 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE)-dependent hypertension in human cytochrome P450 (CYP) 4A11 transgenic mice: normalization of blood pressure by sodium restriction, hydrochlorothiazide, or blockade of the type 1 angiotensin II receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 16904–16919 10.1074/jbc.M116.732297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hollenberg P. F., and Hager L. P. (1973) The P-450 nature of the carbon monoxide complex of ferrous chloroperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 248, 2630–2633 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Augusto O., Beilan H. S., and Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (1982) The catalytic mechanism of cytochrome P-450: Spin-trapping evidence for one-electron substrate oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11288–11295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Harada N., Miwa G. T., Walsh J. S., and Lu A. Y. (1984) Kinetic isotope effects on cytochrome P-450-catalyzed oxidation reactions: evidence for the irreversible formation of an activated oxygen intermediate of cytochrome P-448. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3005–3010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gorsky L. D., Koop D. R., and Coon M. J. (1984) On the stoichiometry of the oxidase and monooxygenase reactions catalyzed by liver microsomal cytochrome P-450: products of oxygen reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 6812–6817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shiro Y., Fujii M., Iizuka T., Adachi S., Tsukamoto K., Nakahara K., and Shoun H. (1995) Spectroscopic and kinetic studies on reaction of cytochrome P450nor with nitric oxide: implication for its nitric oxide reduction mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1617–1623 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zuber M. X., John M. E., Okamura T., Simpson E. R., and Waterman M. R. (1986) Bovine adrenocortical cytochrome P-45017α: regulation of gene expression by ACTH and elucidation of primary sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2475–2482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nebert D. W., and Gelboin H. V. (1968) Substrate-inducible microsomal aryl hydroxylase in mammalian cell culture. II. Cellular responses during enzyme induction. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 6250–6261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Burkhart B. A., Harada N., and Negishi M. (1985) Sexual dimorphism of testosterone 15α-hydroxylase mRNA levels in mouse liver. cDNA cloning and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 15357–15361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Morgan E. T., MacGeoch C., and Gustafsson J. A. (1985) Hormonal and developmental regulation of expression of the hepatic microsomal steroid 16α-hydroxylase cytochrome P-450 apoprotein in the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 11895–11898 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hardwick J. P., Song B. J., Huberman E., and Gonzalez F. J. (1987) Isolation, complementary DNA sequence, and regulation of rat hepatic lauric acid 2-hydroxylase (cytochrome P-450LAω): identification of a new cytochrome P-450 gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 801–810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Muerhoff A. S., Griffin K. J., and Johnson E. F. (1992) The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor mediates the induction of CYP4A6, a cytochrome P450 fatty acid ω-hydroxylase, by clofibric acid. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 19051–19053 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sutter T. R., Tang Y. M., Hayes C. L., Wo Y. Y., Jabs E. W., Li X., Yin H., Cody C. W., and Greenlee W. F. (1994) Complete cDNA sequence of a human dioxin-inducible mRNA identifies a new gene subfamily of cytochrome P450 that maps to chromosome 2. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13092–13099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Honda S., Morohashi K., Nomura M., Takeya H., Kitajima M., and Omura T. (1993) Ad4BP regulating steroidogenic P-450 gene is a member of steroid hormone receptor superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 7494–7502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sogawa K., Gotoh O., Kawajiri K., Harada T., and Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1985) Complete nucleotide sequence of a methylcholanthrene-inducible cytochrome P-450 (P-450d) gene in the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 5026–5032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Suwa Y., Mizukami Y., Sogawa K., and Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1985) Gene structure of a major form of phenobarbital-inducible cytochrome P-450 in rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 7980–7984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Poland A., Glover E., and Kende A. S. (1976) Stereospecific, high affinity binding of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by hepatic cytosol. Evidence that the binding species is a receptor for induction of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 4936–4946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Perdew G. H., and Poland A. (1988) Purification of the Ah receptor from C57BL/6J mouse liver. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 9848–9852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chan W. K., Yao G., Gu Y. Z., and Bradfield C. A. (1999) Cross-talk between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hypoxia inducible factor signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12115–12123 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Poulos T. L., Finzel B. C., Gunsalus I. C., Wagner G. C., and Kraut J. (1985) The 2.6-Å crystal structure of Pseudomonas putida cytochrome P-450. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 16122–16130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gotoh O. (1992) Substrate recognition sites in cytochrome P450 family 2 (CYP2) proteins inferred from comparative analysis of amino acid and coding nucleotide sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 83–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Larson J. R., Coon M. J., and Porter T. D. (1991) Alcohol-inducible cytochrome P-450 IIE1 lacking the hydrophobic NH2-terminal segment retains catalytic activity and is membrane-bound when expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 7321–7324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li Y. C., and Chiang J. Y. (1991) The expression of a catalytically active cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase cytochrome P-450 in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19186–19191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shimizu T., Tateishi T., Hatano M., and Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1991) Probing the role of lysines and arginines in the catalytic function of cytochrome P450d by site-directed mutagenesis. Interaction with NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 3372–3375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Halpert J. R., and He Y. (1993) Engineering of cytochrome P450 2B1 specificity: conversion of an androgen 16β-hydroxylase to a 15α-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4453–4457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yano J. K., Wester M. R., Schoch G. A., Griffin K. J., Stout C. D., and Johnson E. F. (2004) The structure of human microsomal cytochrome P450 3A4 determined by X-ray crystallography to 2.05 Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38091–38094 10.1074/jbc.C400293200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Porubsky P. R., Battaile K. P., and Scott E. E. (2010) Human cytochrome P450 2E1 structures with fatty acid analogs reveal a previously unobserved binding mode. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22282–22290 10.1074/jbc.M110.109017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hsu M. H., Baer B. R., Rettie A. E., and Johnson E. F. (2017) The crystal structure of cytochrome P450 4B1 (CYP4B1) monooxygenase complexed with octane discloses several structural adaptations for ω-hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 5610–5621 10.1074/jbc.M117.775494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Narhi L. O., and Fulco A. J. (1986) Characterization of a catalytically self-sufficient 119,000-dalton cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase induced by barbiturates in Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 7160–7169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lepesheva G. I., Podust L. M., Bellamine A., and Waterman M. R. (2001) Folding requirements are different between sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and human or fungal orthologs. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28413–28420 10.1074/jbc.M102767200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Leys D., Mowat C. G., McLean K. J., Richmond A., Chapman S. K., Walkinshaw M. D., and Munro A. W. (2003) Atomic structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP121 to 1.06 Å reveals novel features of cytochrome P450. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5141–5147 10.1074/jbc.M209928200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Lamb D. C., Skaug T., Song H.-L., Jackson C. J., Podust L. M., Waterman M. R., Kell D. B., Kelly D. E., and Kelly S. L. (2002) The cytochrome P450 complement (CYPome) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24000–24005 10.1074/jbc.M111109200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hargrove T. Y., Friggeri L., Wawrzak Z., Qi A., Hoekstra W. J., Schotzinger R. J., York J. D., Guengerich F. P., and Lepesheva G. I. (2017) Structural analyses of Candida albicans sterol 14α-demethylase complexed with azole drugs address the molecular basis of azole-mediated inhibition of fungal sterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 6728–6743 10.1074/jbc.M117.778308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sibbesen O., Koch B., Halkier B. A., and Møller B. L. (1995) Cytochrome P-450TYR is a multifunctional heme-thiolate enzyme catalyzing the conversion of l-tyrosine to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde oxime in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3506–3511 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Pan Z., Durst F., Werck-Reichhart D., Gardner H. W., Camara B., Cornish K., and Backhaus R. A. (1995) The major protein of guayule rubber particles is a cytochrome P450: characterization based on cDNA cloning and spectroscopic analysis of the solubilized enzyme and its reaction products. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 8487–8494 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Sherbet D. P., Tiosano D., Kwist K. M., Hochberg Z., and Auchus R. J. (2003) CYP17 mutation E305G causes isolated 17,20-lyase deficiency by selectively altering substrate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48563–48569 10.1074/jbc.M307586200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Wang C., Pallan P. S., Zhang W., Lei L., Yoshimoto F. K., Waterman M. R., Egli M., and Guengerich F. P. (2017) Functional analysis of human cytochrome P450 21A2 variants involved in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 10767–10778 10.1074/jbc.M117.792465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Keber R., Motaln H., Wagner K. D., Debeljak N., Rassoulzadegan M., Ačimovic J., Rozman D., and Horvat S. (2011) Mouse knockout of the cholesterogenic cytochrome P450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase (Cyp51) resembles Antley-Bixler syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29086–29097 10.1074/jbc.M111.253245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Stiles A. R., McDonald J. G., Bauman D. R., and Russell D. W. (2009) CYP7B1: one cytochrome P450, two human genetic diseases, and multiple physiological functions. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28485–28489 10.1074/jbc.R109.042168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Gonzalez E., and Guengerich F. P. (2017) Kinetic processivity of the two-step oxidations of progesterone and pregnenolone to androgens by human cytochrome P450 17A1. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 13168–13185 10.1074/jbc.M117.794917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Lambeth J. D., and Pember S. O. (1983) Cytochrome P-450scc-adrenodoxin complex: reduction properties of the substrate-associated cytochrome and relation of the reduction states of heme and iron-sulfur centers to association of the proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 5596–5602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Guengerich F. P., Waterman M. R., and Egli M. (2016) Recent structural insights into cytochrome P450 function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 37, 625–640 10.1016/j.tips.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Gainer J. V., Bellamine A., Dawson E. P., Womble K. E., Grant S. W., Wang Y., Cupples L. A., Guo C. Y., Demissie S., O'Donnell C. J., Brown N. J., Waterman M. R., and Capdevila J. H. (2005) Functional variant of CYP4A11 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthase is associated with essential hypertension. Circulation 111, 63–69 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151309.82473.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Frank D. J., Madrona Y., and Oritz de Montellano P. R. (2014) Cholesterol ester oxidation by mycobacterial cytochrome P450. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 30417–30425 10.1074/jbc.M114.602771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]