Abstract

Interventions can enhance students’ motivation for reading, but few researchers have assessed the effects of the specific motivation-enhancing practices that comprise these interventions. Even fewer have evaluated how students’ perceptions of different intervention practices impact their later motivation and academic outcomes. In this study, we utilized data from a study of Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction, a program designed to enhance seventh-grade students’ reading comprehension and motivation. We examined the effects of students perceiving one practice from this intervention, emphasizing the importance of reading, which was designed to enhance their task values for reading (Eccles-Parsons et al, 1983). Unexpectedly, structural equation modeling analyses showed that students’ perceptions of importance support predicted their later competence-related beliefs, but not their task values. Students’ competence-related beliefs predicted their reading comprehension and behavioral engagement, whereas students’ task values predicted reading engagement. However, there were no significant indirect effects of perceiving importance support on students’ reading outcomes.

Keywords: expectancy-value theory, Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction, motivation intervention, reading motivation, reading engagement

Students often describe non-fiction information texts as difficult, boring, and unimportant to them (Alvermann, 2002; Guthrie, Klauda, & Morrison, 2012; Guthrie, Wigfield, & Klauda, 2012). Such beliefs can impact negatively students’ motivation for reading and their performance in the subject areas that use the information texts (see Wigfield, Tonks, & Klauda, 2016, for review). Because many secondary schools still use information texts as a primary source of course material (O’Brien, Stewart, & Beach, 2009) it is critical to ensure that students are sufficiently motivated to engage with and comprehend these texts.

One way to address this is through changing reading instructional practices to enhance students’ motivation. Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) is an instructional program that has been successful in enhancing different-aged students’ motivation for reading and comprehension of information texts (Guthrie, Wigfield, & Klauda, 2012; Guthrie, Klauda, & Ho, 2013). However, in CORI, teachers implement several motivation-enhancing practices and so we do not know how each of the practices impacts student outcomes. One of the CORI practices asks teachers to emphasize to students the importance of reading in order to enhance students’ valuing of reading. In this paper we examine data from a study of CORI conducted in middle school to examine the effects of the practice of importance support on seventh-grade students’ motivational beliefs and values, reading engagement, and reading comprehension. We also build on prior literature to focus on students’ perceptions of their teachers’ implementation of importance support, in order to examine whether students who perceived more of this practice being implemented in their classrooms benefitted more from it.

The CORI practice of importance support is grounded in Eccles and colleagues’ expectancy-value theory (EVT; Eccles-Parsons et al., 1983; see Wigfield et al., 2016 for review). EVT theorists posit that the two most proximal beliefs that determine students’ motivation for a given academic task are their expectancies for how well they will do on the task, and the extent to which they value the task. Students’ expectancies are highly related to their beliefs about their current ability in a domain (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995), so as other researchers have done we combine these constructs into a broader variable called “competence-related beliefs” in this article. EVT researchers posit that students’ task values are mainly determined by three factors: how useful they think the task is (i.e., utility value), the task’s importance to their sense of identity (i.e., attainment value), and how interesting they think the task is (i.e., intrinsic value) (Eccles-Parsons et al., 1983; Wigfield et al., 2016). Researchers have demonstrated that students’ competence-related beliefs and task values relate positively to each other and both predict positively students’ outcomes in different academic subject areas, including reading (e.g., Durik, Vida, & Eccles, 2006; Eccles & Wigfield, 1995). Students’ competence-related beliefs tend to be a stronger direct predictor of grades and test scores than task values (see Wigfield et al., 2016 for review).

Along with motivation, Guthrie, Wigfield and their colleagues focused on students’ engagement in reading and posited that a key goal of CORI is enhancing reading engagement (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Guthrie, Wigfield, & You, 2012). They defined engaged readers as motivated, strategic, knowledgeable, and actively involved in reading (see Christenson, Reschly, & Wylie, 2012; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004, for further discussion). Students’ competence-related beliefs and task values both predict positively their engagement in reading and other subject areas. (e.g., Guthrie, Wigfield, & You, 2012; Wang & Eccles, 2013). Fredricks et al. (2004) proposed that engagement has behavioral, cognitive, and emotional components. We focus on students’ behavioral engagement in this paper because it is a critical predictor of reading comprehension (Guthrie, Wigfield, & You, 2012).

We examine the practice of importance support in the present study because it was designed to enhance students’ utility value and attainment value for reading (Guthrie & Klauda, 2014). Over the last decade many researchers conducting EVT-based motivation interventions in math and science have shown that intervention practices designed to enhance students’ valuing have improved students’ subsequent motivational beliefs and values, and achievement. Most of these interventions ask students to think about how what they are learning in a course relates to their lives, so that they come to perceive the course material as more useful (e.g., Gaspard et al., 2015; Harackiewicz, Canning, Tibbetts, Priniski, & Hyde, 2016; Hulleman, Godes, Hendricks, & Harackiewicz, 2010). There is a need to understand how similar intervention practices would affect students in reading. To our knowledge only one value-targeting intervention has been done in reading: Its purpose was to educate students about career relevance of course material across several academic subjects, but it failed to improve students’ reading grades (Woolley, Rose, Orthner, Akos, & Jones-Sanpei, 2013).

Another contribution of the present study is that by using data from a study of CORI, we are examining a teacher-implemented rather than a researcher-implemented motivation intervention. To date researchers have implemented all value-targeting motivation interventions, either by sending students outside-of-class assignments (e.g., Harackiewcz et al., 2016) or by administering the intervention themselves in class (e.g., Gaspard et al., 2015). As important as the results of extant value-targeting interventions are, it also is important to examine teacher-implemented interventions. Researchers may not be able to implement interventions in many different classrooms at once, so if teachers can do so effectively then a successful intervention practice perhaps could be scaled up more readily.

To examine how students responded to importance support in the present study, we examined students’ perceptions of their teachers’ implementation of importance support in reading, and how those perceptions related to students’ subsequent reading motivation, engagement in reading and comprehension. Consistent with a long tradition of research in social psychology suggesting that beliefs can define reality (see Jussim, 1991, for review), it is often the case that teachers implement a given intervention practice with fidelity, but students do not perceive the practice in a way that engages them in the psychological processes that it was designed to impact (O’Donnell, 2008). Some students might perceive more or less of a given practice compared to their peers, which in turn may cause the practice to affect students’ outcomes more or less strongly. To understand directly how teacher-delivered intervention practices affect students, researchers can examine how students’ perceptions of a particular practice being implemented in a classroom impact their later motivation and reading outcomes. To the best of our knowledge only Guthrie and Klauda (2014), using the same data we are using, have examined perceptions of instructional practices during a reading-focused motivation intervention. Furthermore, they primarily used the student perception data as an alternative way to measure implementation fidelity, rather than examining how students’ perceptions of intervention implementation related to their outcomes.

As noted earlier we addressed the effects of perceiving importance support during CORI using data from a study of CORI’s effectiveness in improving seventh grade middle school students’ reading motivation, engagement, and comprehension of history information texts (see Guthrie et al., 2013; Guthrie, Wigfield, & Klauda 2012, for detailed descriptions of CORI). Consistent with prior CORI studies, Guthrie and Klauda (2014) found (utilizing a “switching replication” design) that students’ reading comprehension and motivation were higher during CORI than when the same students received the district’s traditional reading instruction program. In this study of CORI teachers implemented four different motivation-targeting intervention practices, one of which was importance support (see below for more information). Guthrie and colleagues (e.g., Guthrie & Humenick, 2004; Guthrie, Wigfield, & Klauda, 2012) devised the practices from principles in several motivation theories, and from interviewing adolescent students.

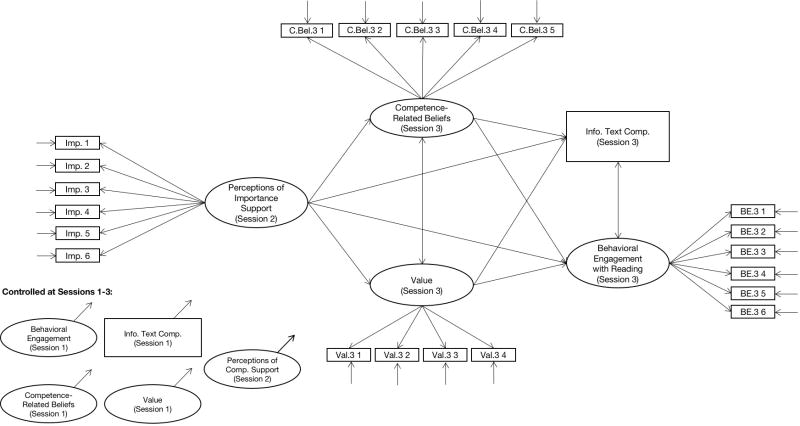

We used structural equation modeling to examine within-group variation in CORI students’ perceptions of importance support, modeling how these perceptions related to students’ later motivational beliefs and values, reading engagement, and reading achievement. We controlled for students’ prior competence-related beliefs, task values, behavioral engagement, and reading comprehension in the model, in order to have a clearer sense of how perceiving importance support during CORI affected each outcome. Additionally, we controlled for students’ perceptions of another CORI practice based in EVT that was designed to provide support for students’ competence-related beliefs in reading. Controlling for perceptions of competence support helped isolate the effects of students’ perceptions of importance support, versus their perceptions of EVT-related motivation support in CORI more broadly.

Our study had the following specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Students’ perceptions of importance support will predict positively their task values, but not their competence-related beliefs.

Hypothesis 2: Students’ competence-related beliefs will directly (and positively) predict their reading comprehension, and both competence-related beliefs and task values will directly and positively predict their reading engagement. We did not make specific hypotheses about whether students’ task values would directly impact reading comprehension, because this relation is found in some prior EVT-based studies (e.g., Durik et al., 2006) but not others (e.g., Solheim, 2011).

Hypothesis 3: Students’ perceptions of importance support will not predict their later reading comprehension and reading engagement directly. Guthrie and Wigfield’s (2000) engagement model of reading, which provides the overarching framework for CORI, states that the CORI practices should only change students’ reading outcomes as a function of changing their motivation. Consistent with this, we did not expect to find these significant direct relations.

Hypothesis 4: Students’ perceptions of importance support will predict their reading comprehension and reading engagement indirectly, through their competence-related beliefs and/or task values. Based on Guthrie and Wigfield (2000) and Hypotheses 1 and 2, we expected to find a significant indirect effect by which importance support perceptions predicted students’ reading engagement via their task values.

Method

Participants

Participants were 527 seventh-grade students from the Mid-Atlantic United States (28 language arts class sections; 10 teachers; 56.4% female; 74.3% European American, 21.1% African American, 4.0% Asian or Asian American, 0.6% other ethnicities; 25.4% qualified for free or reduced-price lunch). As part of a project called Reading Engagement for Adolescent Learning, 1200 students were assigned to receive the CORI intervention as part of a switching replication experimental design. Half of the teachers in the project provided CORI for the first four weeks of a set instructional period, while the other half of teachers administered traditional reading instruction. After four weeks, the two groups switched (see Guthrie & Klauda, 2014). In this study, we analyzed data only from students whose teachers implemented CORI during the first half of the project (n = 628) in order to assess longitudinal changes in their outcomes. Consistent with Guthrie and Klauda (2014), we excluded from this group 65 students who had individualized education programs, 17 students whose parents did not provide consent, two students who missed school during much of the intervention, 15 students with unusual patterns of self-report data, and two students with no data on classroom membership. This resulted in the sample of 527. Guthrie and Klauda (2014) also excluded students of five teachers whom they perceived did not implement CORI with sufficient fidelity or who were new to the school district. We retained data from these students in order to capture variability in teachers’ implementation of importance support.

Measures

Data were collected at three time points: One week before CORI began (Session 1), one week after CORI ended (Session 2), and five weeks after CORI ended (Session 3). All self-report items were developed by Guthrie and Klauda (2014) and are reported in the appendix.

Perceptions of importance support during CORI

Students’ perceptions of their teachers’ implementation of reading importance support were measured at Session 2 with six items. Students responded on 4-point response scales ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree (α = .84).

Competence-related beliefs and task values

Students’ competence-related beliefs and task values regarding reading information books for school were measured at Session 3 with six items each. Students responded on four-point response scales ranging from Not at All True of Me to Very True of Me (for competence-related beliefs, α = .78; for task values, α = .80; scores are based on less than six items per measure, see Results section).

Behavioral engagement with reading

Students’ behavioral engagement with reading was measured at Session 3 using a measure of “dedication to reading” which is defined as a disposition towards and willingness to put forth time, effort, and persistence on reading activities (Guthrie, Wigfield, & Klauda, 2012). This construct overlaps conceptually with behavioral engagement so we describe it as behavioral engagement throughout this article. This scale included six items with 4-point response scales ranging from Not at All True of Me to Very True of Me (α = .81).

Information text comprehension

Students’ ability to understand history information texts at Session 3 was assessed with a test that consisted of two easier (60-100 words, 5th-7th grade reading level) and three harder (250-300 words, 8th grade–college reading level) passages about historical topics. Students answered five multiple-choice questions about each passage, which assessed understanding of words, phrases, or concepts, word meanings, relational understanding, or synopsis of the text. Students received a different form of the test at each session, with form administration counterbalanced across the time points. A linking process was used to adjust raw scores across the forms, based on linear equating (see Guthrie and Klauda, 2014, for more discussion of this measure). We analyze scores in terms of percentage correct on students’ adjusted test scores (for students’ raw test scores, reliability statistics were as follows for the three test forms: .59 ≤ αs ≤ .69 at Session 1; .58 ≤ αs ≤ .69 at Session 3).

Control variables

Measures of baseline competence-related beliefs (α = .62), task values (α = .60), reading engagement (α =.70), and information text comprehension were collected at Session 1. Additionally, we used five items to measure students’ perceptions of teacher’s engaging in support for their competence in reading during CORI (α = .77).

Demographic characteristics

Demographic information (e.g., gender, ethnicity, free and reduced price lunch status) was collected from administrative records.

Procedure

Teachers in this study implemented CORI for four weeks, then implemented the district’s traditional reading instruction for four weeks. At each measurement time point, assessments were given to students by their reading/language arts teachers, with research assistants present.

CORI focused on students’ reading of texts regarding the U.S. Civil War (see Guthrie & Klauda, 2014, for full description). Teachers received two half-days of professional development and a teachers’ guide to learn about implementing CORI, although they were not required to use the guide verbatim. During the intervention, teachers focused on one sub-topic relevant to the Civil War each day (e.g., How do you explain different views of slavery in the North and the South?). They led their class in group instruction regarding this topic, then engaged students in activities such as guided or independent reading, or text-based writing (see Guthrie & Klauda, 2014 for full description). The texts utilized by teachers included books about Civil War topics (e.g., trade) and biographies (e.g., Harriet Tubman), which ranged in difficulty.

Teachers implemented reading strategy instructional practices each day to improve students’ reading comprehension. They also engaged in four practices designed to enhance students’ motivational beliefs and values, focusing on one practice each week. The focus on importance support was in Week 3. As noted above, another CORI practice that was based in EVT was helping students build competence in reading. The other two CORI practices were based in self-determination theory and theories of social motivation: providing choice to foster students’ intrinsic motivation, and offering opportunities for students to collaborate to foster social motivation (see Guthrie & Klauda, 2014, for full discussion).

To emphasize the importance of reading, teachers asked students to explain why texts helped them think of new ideas or support their arguments, and to relate information from the texts to their own experiences. These activities were designed to promote students’ task values for reading (Guthrie & Klauda, 2014). In CORI, students reflected on the importance of specific pieces of the texts that they read for accomplishing specific classroom activities. This differed from prior value-targeting intervention studies, in which the intervention prompts asked students to relate any topic from their course material to any aspect of their lives (e.g., Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009). The rationale for using text-specific importance support practices in CORI was that it would be easier for middle school students to grasp the concept of value for daily literacy activities than to think about the abstract value of reading skills in their lives.

Assessing implementation fidelity of CORI was not critical for addressing the goals of the present study, which focused on within-group variation in students’ perceptions of importance support during CORI. However, we did confirm that the students in our sample, who received CORI, perceived more importance support at Session 2 (M = 2.87; SD = 0.70) compared to students who had received traditional instruction during that time period (M = 2.59; SD = 0.71), β = 0.15, t (899) = 5.40, p < .001.

Data Analytic Strategy

We used structural equation modeling to assess relations among: (a) students’ perceptions of importance support during CORI (measured at Session 2), (b) students’ competence-related beliefs and task values for information text reading (measured at Session 3), and (c) students’ behavioral engagement with reading and information text comprehension (measured at Session 3). We controlled for students’ perceptions of the other EVT-related instructional practice in CORI - supporting students’ competence in reading (measured at Session 2) - to ensure that we were isolating the effects of perceiving importance support. We also controlled for students’ prior competence-related beliefs, task values, behavioral engagement with reading, and information text comprehension scores (measured at Session 1). Reading competence-related beliefs and values were measured at the same time point as engagement and information text comprehension (Session 3), but we treated the motivational constructs as predictors of reading engagement and comprehension based on theoretical arguments regarding their relations (e.g., Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000).

We used a two-phase modeling process in MPlus Version 7, with full information maximum likelihood estimation, to address missing data (Graham, 2009). We first estimated a measurement model for all variables, to ensure that each item loaded onto its respective latent construct, and that the latent constructs formed distinct factors. We then estimated the structural relations among variables. All constructs were modeled as latent variables except information text comprehension, which was not scored as a function of students’ reports on individual items. We set the variance of each latent factor equal to 1 to provide scale. Students were nested within 10 teachers and 28 classrooms, so we used a robust maximum likelihood estimator with cluster-robust standard errors (MLR estimation), using class section as a cluster variable and teacher as a stratification variable. Therefore MPlus adjusted the fit statistics and standard errors of all estimates in order to account for nonnormality of any indicator variables and dependency of observations as a function of nesting (Muthen & Muthen, 2012). We assessed model fit using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values greater than 0.90 and 0.95 are typically considered to reflect acceptable and excellent fits to the data, respectively (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh, Wen, & Hau, 2004). RMSEA values of less than 0.06 and SRMR values of less than 0.08 are considered to reflect good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Analysis of the Data with Structural Equation Modeling

Descriptive statistics for manifest variables are reported in Table 1. Missing data was low (3.9% - 9.2%).

Table 1.

Manifest Descriptive Statistics for Scales Included in Structural Equation Models

| N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | |||

| Competence-Related Beliefs | 502 | 3.17 | 0.41 |

| Task Values | 482 | 3.07 | 0.49 |

| Behavioral Engagement with Reading | 506 | 3.11 | 0.56 |

| Information Text Comprehension | 501 | 51.95 | 16.08 |

| Session 2 | |||

| Perceptions of Importance Support | 499 | 2.87 | 0.70 |

| Perceptions of Competence Support | 501 | 2.59 | 0.64 |

| Session 3 | |||

| Competence-Related Beliefs | 497 | 3.07 | 0.58 |

| Task Values | 495 | 2.80 | 0.69 |

| Behavioral Engagement with Reading | 502 | 3.02 | 0.61 |

| Information Text Comprehension | 505 | 53.18 | 17.66 |

Note. Scores on Information Text Comprehension Measure are reported in terms of percentage correct out of 25. The range of scores was 1 - 4 for all self-report variables.

Measurement phase

The initial measurement model showed acceptable fit, χ2 (1084) = 1646.66, p < .001; RMSEA = .03; CFI = .91; TLI = .91; SRMR = .05. We then omitted from both sessions one value item that had a low standardized loading at Session 1 (< .40). We also examined suggested modification indices and eliminated two items (one value item and one competence-related belief item) that cross-loaded onto multiple factors. Finally, we added an error covariance term between the same self-efficacy item at Session 1 and Session 3 (see appendix for specific items). This improved fit, χ2 (816) = 1146.43, p < .001; RMSEA = .03; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05. Correlations among latent variables from the final measurement model are reported in Table 2. We moved forward with this model for the structural phase of analyses; see Figure 1 for depiction.

Table 2.

Latent Correlations Among Scales From Final Measurement Model

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | ||||||||||

| 1. | Competence-Related Beliefs | |||||||||

| 2. | Task Values | .48** | ||||||||

| 3. | Behavioral Engagement with Reading | .36** | .40** | |||||||

| 4. | Information Text Comprehension | .30** | −.17** | .07 | ||||||

| Session 2 | ||||||||||

| 5. | Perceptions of Importance Support | .06 | .49** | .25** | −.14* | |||||

| 6. | Perceptions of Competence Support | .16* | .38** | .22* | −.06 | .79** | ||||

| Session 3 | ||||||||||

| 7. | Competence-Related Beliefs | .72** | .24** | .17* | .32** | .09 | .11 | |||

| 8. | Task Values | .18** | .60** | .34** | −.06 | .53** | .42** | .40** | ||

| 9. | Behavioral Engagement with Reading | .32* | .35** | .66** | .16** | .28** | .26** | .45** | .68** | |

| 10. | Information Text Comprehension | .28** | −.11† | .16* | .63** | −.15** | −.10 | .55** | −.01 | .21** |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01

Figure 1.

Final structural equation model tested in the study.

Structural phase

Coefficients for the paths included in the structural model are presented in Figure 2. Results did not support the first hypothesis that students’ perceptions of importance support would predict their reading task values but not their competence-related beliefs. Instead, students’ Session 2 perceptions of importance support predicted their Session 3 competence-related beliefs, but not their task values. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, students’ Session 3 competence-related beliefs and task values both predicted behavioral engagement with reading, and Session 3 competence-related beliefs (but not task values) predicted reading comprehension. Results also supported Hypothesis 3, in that students’ perceptions of importance support did not predict directly any reading outcomes. However, we did not find the predicted relations from Hypotheses 1 and 2 that would result in the indirect effect we had expected for Hypothesis 4. We did find that students’ perceptions of importance support predicted their competence-related beliefs positively, which in turn predicted both their reading engagement and comprehension positively. However, the tests of indirect effects from perceiving importance support to either reading outcome via competence-related beliefs were not significant.

Figure 2.

Structural model results. Standardized path coefficients are depicted; *p < .05; **p < .01. Paths between each covariate and the constructs in the model, and covariances among all covariates, are included in the model but were not depicted here.

Discussion

This study contributes to the literature on motivation-targeting interventions because it is one of the first to examine the specific impact of a motivation-targeting intervention practice (in this case importance support) that is part of a multi-faceted reading intervention. This also extends the value-targeting intervention literature to the domain of reading. Additionally, the intervention study that provided the data for this article was implemented by teachers; most prior value-targeting motivation interventions were implemented by researchers. Finally, this is one of the first studies to explore how students’ perceptions of specific motivation intervention practices relate to their outcomes. This provides a novel way to assess how intervention practices are perceived by students and illustrates the psychological mechanisms by which perceiving intervention practices can affect students’ motivational beliefs and values. We discuss each major finding from this study and its implications in turn.

The first finding was that students who perceived more importance support at Session 2 reported higher competence-related beliefs at Session 3, but not higher task values. We had predicted the opposite pattern: that perceiving importance support would predict students’ task values but not competence-related beliefs. One explanation for these seemingly counterintuitive findings comes from considering the activities students were working on when teachers were providing importance support. During these activities, students were prompted to use texts to help them with classroom discussions and assignments, with a goal that students would perceive the texts as useful for helping them succeed on these tasks. Bandura (1997) and others posit that success experiences are critical determinants of competence-related beliefs; given that the tasks related to importance support were designed to help students succeed, they likely influenced their competence-related beliefs. Furthermore, perceived competence is central to students’ sense of self-worth (Marsh, Martin, Yeung, & Craven, 2017), so students may be highly sensitive to clues regarding their competence in academic context. As a result, students may interpret teacher practices as being competence-related even if they were not intended to affect perceived competence. Together, these factors could have helped students perceive themselves as being more competent to read the texts in addition to, or instead of, perceiving that reading was valuable.

The results observed here might have differed from the results of prior studies because CORI was done in reading and/or was a teacher-delivered intervention, but we do not believe this is likely. Other prior task-value-focused interventions, implemented by researchers in science and math, also have increased students’ competence-related beliefs (Brisson et al., 2017; Canning & Harackiewicz, 2015; Hulleman et al., 2017). Those researchers discussed how students’ competence beliefs and task values are positively related, and so an intervention designed to enhance one might actually affect the other in some circumstances. Researchers in all academic domains should explore the possibility that sometimes value-focused interventions might be interpreted as cues relevant to students’ competence-related beliefs.

It was also unexpected in that importance support did not predict students’ task values, and this finding differs from the design of the importance support practice and from findings of prior value-targeting intervention studies (e.g., Gaspard et al., 2015; Hulleman et al., 2010). One likely explanation for this difference was that the importance support practices in CORI were more specific than prior studies’ intervention practices. In CORI, teachers focused on particular student-text interactions. For example, teachers asked students to use texts to support their ideas in discussions with peers, and to think about what parts of specific texts were most relevant to their lives. The task-specific focus was designed to help students see the importance of reading for their classroom activities. It is possible that middle school students did not make the connection between perceiving that a text was useful for a specific class activity to the broader understanding that reading would be useful in their lives. Prior value-targeting interventions asked students to think about the value of coursework more broadly, and also included older students as participants who likely were more capable of thinking about the utility value of their course material in an abstract way (e.g., Gaspard et al., 2015; Harackiewicz et al., 2016; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009). Future researchers may want to test whether practices that help students reflect more broadly, versus more specifically, about the importance of reading skills are more successful at boosting perceptions of value.

It is also possible that the CORI importance support practice would impact students’ task values in other circumstances. Students’ competence-related beliefs and task values are correlated, and both Bandura (1997) and Jacobs et al. (2002) have posited that students’ competence-related beliefs predict increases in their valuing of activities. Thus students’ perceptions of importance support in CORI may eventually improve their task values through improving their competence-related beliefs. Additionally, Guthrie and Klauda (2014), in correlational analyses that controlled for students’ perceptions of the other CORI practices, reported that students’ perceptions of importance support correlated significantly and positively with their task values; perhaps with our somewhat different sample and modeling strategy, the relation was present but was not large enough to be significant. Finally, our measure of task values included few items; it is possible that we did not capture the nuances of task values well enough to capture changes in it as a result of perceiving importance support.

Our second major finding was that students’ competence-related beliefs predicted their Session 3 reading comprehension and behavioral reading engagement, and task values predicted their reading engagement. These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 2 and with prior EVT research and theory (e.g., Durik et al., 2006; Wang & Eccles, 2013). Importantly, they extend these findings to the intervention setting.

Our third major finding was that there were no significant direct relations between perceiving importance support and students’ reading engagement and comprehension, after accounting for the relation between these perceptions and motivational beliefs and values. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 3 and with the engagement model of reading underlying CORI, which states that instructional practices impact reading outcomes indirectly through students’ motivational beliefs and values (e.g., Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Guthrie et al., 2013). However, we did not find support for Hypothesis 4, that perceiving importance support would impact students’ reading engagement indirectly via task values, and more broadly we found no evidence for any indirect effects of perceiving importance support on students’ reading outcomes. Although it is worthwhile for an intervention to improve students’ motivational beliefs and values, many researchers hope that their intervention practices will also promote students’ academic outcomes. It will be critical for researchers to test whether perceiving importance support would produce significant indirect effects via students’ competence-related beliefs or task values in other studies, before using this practice to boost students’ reading outcomes.

Limitations and Next Steps

The main conclusion of the present study is that importance support in CORI may be most beneficial to students in its ability to improve their perceived competence for reading information texts. Future researchers should address the limitations of the present study to explore this finding more thoroughly. First, researchers should test the generality of this model across different age groups, subject areas, kinds of reading material, and ways of assessing students’ reading comprehension and/or reading engagement. Second, the motivational constructs, behavioral engagement, and reading comprehension measures were all administered at the same time point (Session 3). Researchers should assess these relations in more long-term longitudinal studies. Third, we examined relations overall for the group of students experiencing CORI. A critical next step in this work is to examine whether these relations are similar across subgroups of students, such as those with high or low prior competence-related beliefs and/or values in reading, or male and female students.

As more work is done that extends the present study’s findings, we will gain a clearer understanding of how students respond to value-targeting intervention practices in reading. Results of this new work will shed further light on when and how different classroom instructional practices designed to enhance students’ motivation, engagement, and achievement indeed do so.

Highlights.

- What is already known about this topic

- Interventions targeting students’ task values have improved their academic outcomes in science and math.

- Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) is a successful multi-faceted reading comprehension intervention program, implemented by classroom teachers. It includes a variety of theoretically-based practices to enhance students’ reading motivation, including the practice of importance support to increase students’ task values.

- What this paper adds

- Structural equation modeling analyses showed that students who perceived more importance support during CORI reported higher competence-related beliefs, but not task values.

- This study is one of very few that have measured students’ perceptions of individual teacher-delivered motivation-enhancing practices in the reading classroom.

- Implications for theory, policy, or practice

- The findings show that students who perceive more of the practice of importance support show higher motivation to learn.

- However, results suggest that value-targeting intervention practices might affect students’ competence-related beliefs more strongly than their task values in some circumstances.

Acknowledgments

The writing of this article was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Postdoctoral Research Fellowship 1714481 and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship DGE 1322106 to the first author. The work on the REAL project was supported by Grant R01HD052590 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to the fourth author. The work of the third author was supported by the Postdoc Academy of the Hector Research Institute of Education Sciences and Psychology at the University of Tübingen, funded by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Emily Rosenzweig, 1202 West Johnson Street, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Appendix: All items included in measurement phase of study

| Construct | Standardized Loading of Item on Factor in Final Measurement Model | Item Wording |

|---|---|---|

| Competence-Related Beliefs | S1: .51; S3: .61 | 1. I could understand all the readings |

| S1: .61; S3: .65 | 2. I could correctly answer questions about the readings | |

| S1: .48; S3: .72 | 3. The key points in the text were clear to me | |

| S1: .41; S3: .71 | 4. The main ideas of the readings were easy to find | |

| S1: .49; S3: .56 | 5. I could figure out what unfamiliar words meant *Allowed for error covariance on this item between S1 and S3 |

|

| Excluded due to cross loadings | 6. I figured out how different chapters fit together in the readings | |

|

| ||

| Task Values | S1: .43; S3: .66 | 1. The readings gave me useful knowledge |

| S1: .50; S3: .72 | 2. Studying the materials was beneficial to me | |

| S1: .58; S3: .70 | 3. Understanding the reading materials will help me next year | |

| S1: .54; S3: .76 | 4. I learned something valuable from the reading assignments | |

| Excluded due to low loading on target factor | 5. I could relate the readings to my life | |

| Excluded due to cross loadings | 6. It was very important to me to do my reading | |

|

| ||

| Perceptions of Competence Support | My teacher… | |

| .52 | 1. Said I did well when I read aloud | |

| .55 | 2. Usually knew when I needed help | |

| .69 | 3. Showed me how to improve in reading | |

| .62 | 4. Almost always let me know when I did something right in class | |

| .67 | 5. Helped me meet challenges in reading | |

|

| ||

| Perceptions of Importance Support | My teacher… | |

| .70 | 1. Discussed how our class readings are important for my future | |

| .77 | 2. Showed me that reading is valuable | |

| .62 | 3. Did not show how class reading is important for me (reverse-coded) | |

| .79 | 4. Taught me that reading our materials is important for me | |

| .70 | 5. Explained that reading gives me useful information | |

| .49 | 6. Emphasized how I can benefit from reading a variety of topics in social studies | |

|

| ||

| Behavioral Engagement with Reading Information Texts | S1: .51; S3: .64 | 1. I spent as much time as needed to complete my reading homework |

| S1: .65; S3: .74 | 2. For every assignment, I worked hard | |

| S1: .58; S3: .62 | 3. I made sure I had enough time to complete my reading assignments | |

| S1: .43; S3: .46 | 4. Even if the reading assignments were difficult, I completed them | |

| S1: .42; S3: .63 | 5. I went above and beyond what was expected of me in reading | |

| S1: .62; S3: .77 | 6. I put a lot of effort into reading | |

Contributor Information

Emily Q. Rosenzweig, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Allan Wigfield, University of Maryland.

Hanna Gaspard, Hector Research Institute of Education Sciences and Psychology, University of Tübingen, Germany.

John T. Guthrie, University of Maryland

References

- Alvermann DE. Effective literacy instruction for adolescents. Journal of Literacy Research. 2002;34(2):189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brisson BM, Dicke AL, Gaspard H, Häfner I, Flunger B, Nagengast B, Trautwein U. Short intervention, lasting effects: Promoting students’ competence beliefs, effort, and achievement in mathematics. American Educational Research Journal. 2017 doi: 10.3102/0002831217716084. Online advance publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canning EA, Harackiewicz JM. Teach it, don’t preach it: The differential effects of directly-communicated and self-generated utility–value information. Motivation Science. 2015;1(1):47. doi: 10.1037/mot0000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C. The handbook of research on student engagement. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Durik AM, Vida M, Eccles JS. Task values and ability beliefs as predictors of high school literacy choices: A developmental analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:382–393. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles-Parsons JS, Adler TF, Futterman R, Goff SB, Kaczala CM, Meece JL, Midgley C. Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In: Spence JT, editor. Achievement and achievement motivation. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman; 1983. pp. 75–146. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Wigfield A. In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21(3):215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74(1):59–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspard H, Dicke A, Flunger B, Brisson B, Hafner I, Nagengast B, Trautwein U. Fostering adolescents’ value beliefs for mathematics with a relevance intervention in the classroom. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51(9):1226–1240. doi: 10.1037/dev0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60(1):549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Humenick NM. Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase reading motivation and achievement. In: McCardle P, Chhabra V, editors. The voice of evidence in reading research. Baltimore: Brookes; 2004. pp. 329–354. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Klauda SL. Effects of classroom practices on reading comprehension, engagement, and motivations for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly. 2014;49:387–416. doi: 10.1002/rrq.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Wigfield A. Engagement and motivation in reading. In: Kamil ML, Mosenthal PB, Pearson PD, Barr R, editors. Handbook of reading research. III. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Klauda SL, Ho A. Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly. 2013;48:9–26. doi: 10.1002/rrq.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Klauda S, Morrison D. Motivation, achievement, and classroom contexts for information book reading. In: Guthrie JT, Wigfield A, Klauda SL, editors. Adolescents’ engagement in academic literacy. University of Maryland; College Park: 2012. Jan, pp. 1–51. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Wigfield A, Klauda SL, editors. Adolescents’ engagement in academic literacy. University of Maryland; College Park: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.corilearning.com/research-publications. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JT, Wigfield A, You W. Instructional contexts for engagement and achievement in reading. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 601–634. [Google Scholar]

- Harackiewicz JM, Canning EA, Tibbetts Y, Priniski SJ, Hyde JS. Closing achievement gaps with a utility-value intervention: Disentangling race and social class. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2016;111(5):745–765. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hulleman CS, Kosovich JJ, Barron KE, Daniel DB. Making connections: Replicating and extending the utility value intervention in the classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2017;109(3):387. [Google Scholar]

- Hulleman CS, Godes O, Hendricks BL, Harackiewicz JM. Enhancing interest and performance with a utility value intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102:880–895. [Google Scholar]

- Hulleman CS, Harackiewicz JM. Promoting interest and performance in high school science classes. Science. 2009;326(5958):1410–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.1177067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Lanza S, Osgood DW, Eccles JS, Wigfield A. Ontogeny of children’s self-beliefs: Gender and domain differences across grades one through 12. Child Development. 2002;73:509–527. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Social perception and social reality: A reflection-construction model. Psychological Review. 1991;98(1):54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Martin AJ, Yeung A, Craven R. Competence self-perceptions. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck C, Yeager D, editors. Handbook of Competence and Motivation. New York: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Wen Z, Hau KT. Structural equation models of latent interactions: evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods. 2004;9(3):275. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien D, Stewart R, Beach R. Proficient reading in school: Traditional paradigms and new textual landscapes. In: Christenbury L, Bomer R, Smagorinsky P, editors. Handbook of adolescent literacy research. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CL. Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring fidelity of implementation and its relationship to outcomes in K–12 curriculum intervention research. Review of Educational Research. 2008;78(1):33–84. [Google Scholar]

- Solheim OJ. The impact of reading self-efficacy and task value on reading comprehension scores in different item formats. Reading Psychology. 2011;32(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang MT, Eccles JS. School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction. 2013;28:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Tonks SM, Klauda SL. Expectancy-value theory. In: Wentzel K, Miele D, editors. Handbook of motivation in school. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley ME, Rose RA, Orthner DK, Akos PT, Jones-Sanpei H. Advancing academic achievement through career relevance in the middle grades: A longitudinal evaluation of CareerStart. American Educational Research Journal. 2013;50(6):1309–1335. [Google Scholar]