Abstract

BACKGROUND

There are conflicting data on the effects of antipsychotic medications on delirium in patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).

METHODS

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we assigned patients with acute respiratory failure or shock and hypoactive or hyperactive delirium to receive intravenous boluses of haloperidol (maximum dose, 20 mg daily), ziprasidone (maximum dose, 40 mg daily), or placebo. The volume and dose of a trial drug or placebo was halved or doubled at 12-hour intervals on the basis of the presence or absence of delirium, as detected with the use of the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU, and of side effects of the intervention. The primary end point was the number of days alive without delirium or coma during the 14-day intervention period. Secondary end points included 30-day and 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, and time to ICU and hospital discharge. Safety end points included extrapyramidal symptoms and excessive sedation.

RESULTS

Written informed consent was obtained from 1183 patients or their authorized representatives. Delirium developed in 566 patients (48%), of whom 89% had hypoactive delirium and 11% had hyperactive delirium. Of the 566 patients, 184 were randomly assigned to receive placebo, 192 to receive haloperidol, and 190 to receive ziprasidone. The median duration of exposure to a trial drug or placebo was 4 days (interquartile range, 3 to 7). The median number of days alive without delirium or coma was 8.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.6 to 9.9) in the placebo group, 7.9 (95% CI, 4.4 to 9.6) in the haloperidol group, and 8.7 (95% CI, 5.9 to 10.0) in the ziprasidone group (P=0.26 for overall effect across trial groups). The use of haloperidol or ziprasidone, as compared with placebo, had no significant effect on the primary end point (odds ratios, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.64 to 1.21] and 1.04 [95% CI, 0.73 to 1.48], respectively). There were no significant between-group differences with respect to the secondary end points or the frequency of extrapyramidal symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of haloperidol or ziprasidone, as compared with placebo, in patients with acute respiratory failure or shock and hypoactive or hyperactive delirium in the ICU did not significantly alter the duration of delirium. (Funded by the National Institutes of Health and the VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center; MIND-USA ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01211522.)

DELIRIUM IS THE MOST COMMON MANIfestation of acute brain dysfunction during critical illness, affecting 50 to 75% of patients who receive mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit (ICU).1,2 Patients with delirium have higher mortality,3-5 longer periods of mechanical ventilation and hospital stays,6,7 higher costs,8 and a higher risk of long-term cognitive impairment9-11 than patients who do not have delirium. Delirium also interferes with medical care. Hyperactive delirium can lead to unplanned removal of devices,12 whereas hypoactive delirium prevents participation in nursing interventions, physical therapy, and occupational therapy.13

Haloperidol, a typical antipsychotic medication, is often used to treat hyperactive delirium in the ICU, and surveys suggest that the drug is also used to treat hypoactive delirium14-17 despite two small randomized trials that showed no evidence that haloperidol results in a shorter duration of delirium in the ICU than placebo.18,19 Atypical antipsychotic medications, such as olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone, are also used for this purpose, and one placebo-controlled trial has suggested a benefit,20 whereas another18 showed no evidence of benefit. Therefore, there is conflicting information from small trials, meta-analyses, and practice guidelines on the management of delirium in the ICU.1,21

We conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to examine the effects of haloperidol or ziprasidone on delirium during critical illness. We hypothesized that typical and atypical antipsychotic medications would result in a shorter duration of delirium and coma than placebo and would improve other outcomes.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN AND POPULATION

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial was conducted at 16 medical centers in the United States. Before we randomly assigned the patients to receive a trial drug or placebo, we obtained written informed consent from the patients or their authorized representatives. The institutional review board at each participating center approved the protocol, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The Food and Drug Administration approved an Investigational New Drug application, which was obtained because the intravenous route of administration and the indication for delirium that were used in this trial are not approved for antipsychotic medications (see the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on September 29, 2010, before the first patient was enrolled. The statistical analysis plan was registered at Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mq38r) on March 22, 2018, before the trial-group assignments were unmasked. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

Patients who had been admitted to the participating hospitals were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years of age or older and were receiving treatment in a medical or surgical ICU with invasive or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, vasopressors, or an intraaortic balloon pump, and they were eligible for random assignment to a trial group if they had delirium. We excluded patients who, at baseline, had severe cognitive impairment, as determined by medical record review and the short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE; scores range from 1.0 to 5.0, with higher scores indicating more severe cognitive impairment [a score of ≥4.5 resulted in exclusion because of severe dementia])22; were at high risk for medication side effects because of pregnancy, breast-feeding, a history of torsades de pointes, QT prolongation, a history of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, or allergy to haloperidol or ziprasidone; were receiving ongoing treatment with an antipsychotic medication; were in a moribund state; had rapidly resolving organ failure; were blind, deaf, or unable to speak or understand English; were incarcerated; or were enrolled in another study or trial that prohibited coenrollment. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. Noncomatose patients were excluded if informed consent could not be obtained within 72 hours after inclusion criteria had been met, and comatose patients were excluded if informed consent could not be obtained within 120 hours after inclusion criteria had been met.

TRIAL-GROUP ASSIGNMENT

To minimize the time between the onset of delirium and randomization, we obtained informed consent, when possible, before the onset of delirium; delirium was detected with the use of the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU),23,24 a validated tool that identifies delirium on the basis of an acute change or fluctuating course of mental status plus inattention and either altered level of consciousness or disorganized thinking. If delirium was not present at the time that informed consent was obtained, trained research personnel evaluated patients twice daily until delirium was present or until death, discharge from the ICU, development of an exclusion criterion, or a maximum of 5 days.

When delirium was present at the time of informed consent or during the 5 days after informed consent was obtained and the corrected QT interval was less than 550 msec on a 12-lead electrocardiogram (see the Supplementary Appendix), we randomly assigned the patients, in a 1:1:1 ratio, to receive placebo, haloperidol, or ziprasidone using a computer-generated, permuted-block randomization scheme, with stratification according to trial site. The research personnel, managing clinicians, patients, and their families were not aware of the trial-group assignments.

The trial drugs or placebo were administered intravenously with the use of colorless preparations delivered in identical bags. Immediately after the trial-group assignment, the first dose of a trial drug or placebo was administered: patients younger than 70 years of age received 0.5 ml of placebo (0.9% saline) or 2.5 mg of haloperidol per 0.5 ml or 5 mg of ziprasidone per 0.5 ml, whereas those who were 70 years of age or older received 0.25 ml of placebo or 1.25 mg of haloperidol per 0.25 ml or 2.5 mg of ziprasidone per 0.25 ml. Subsequent doses were administered every 12 hours at approximately 10 a.m. and 10 p.m. Research personnel doubled the volume and dose of the trial drug or placebo if a patient had delirium, was not yet receiving the maximum dose, and had not met criteria that required the trial drug or placebo to be withheld. Patients in the haloperidol group received a dose of up to 10 mg per administration and up to 20 mg per day, and those in the ziprasidone group received a dose of up to 20 mg per administration and up to 40 mg per day.

We halved the volume and dose of a trial drug or placebo if a patient did not have delirium (i.e., had a negative CAM-ICU assessment) for two consecutive assessments and was not yet receiving the minimum dose. We temporarily withheld a trial drug or placebo if a patient did not have delirium for four consecutive assessments or for safety reasons. We permanently discontinued a trial drug or placebo when any of the following occurred: torsades de pointes, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome, new-onset coma due to structural brain disease, or any life-threatening, serious adverse event that was related to the intervention, as determined by an independent data and safety monitoring board. We discontinued a trial drug or placebo after the 14-day intervention period or at ICU discharge, whichever occurred first.

To evaluate the efficacy and to guide volume and dose adjustments of trial drug or placebo, patients were assessed twice daily while they were receiving the intervention by trained research personnel using the CAM-ICU23,24 and the Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS),25,26 a validated, 10-level scale that rates the level of consciousness from unresponsive to physical stimuli (score of −5) to combative (score of +4). We considered any day during which at least one CAM-ICU assessment was positive to be a day with delirium; a positive assessment was considered to indicate hyperactive delirium if the RASS score was higher than 0 and hypoactive delirium if the RASS score was 0 or lower.27

During the period when the patients were receiving a trial drug or placebo and for 4 days after discontinuation, we assessed the patients for side effects. Twice a day, before each administration of the intervention, we assessed the patients for a corrected QT prolongation of 550 msec using telemetry and, if telemetry indicated a corrected QT prolongation of 550 msec, we used 12-lead electrocardiography. Once daily, we assessed extrapyramidal symptoms using a modified Simpson–Angus Scale, a 5-item scale on which each item is scored from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse extrapyramidal symptoms28; akathisia using a 10-point visual-analogue scale; and dystonia using a standardized definition.18

Treating clinicians were educated about the “ABCDE” treatment bundle (assess, prevent, and manage pain; both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials; choice of analgesia and sedation; assess, prevent, and manage delirium; and early mobility and exercise) and were encouraged to perform the treatment bundle to mitigate delirium among the patients in the ICU.29-33 Throughout the trial, we monitored its use and recorded adherence to each component of the bundle daily among the patients for whom informed consent was obtained.

END POINTS

The primary end point was days alive without delirium or coma (defined as the number of days that a patient was alive and free from both delirium and coma during the 14-day intervention period). Secondary efficacy end points included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation (defined as extubation that was followed by at least a 48-hour period during which the patient was alive and free from mechanical ventilation), time to final successful ICU discharge (defined as the last ICU discharge during the index hospitalization that was followed by at least a 48-hour period during which the patient was alive and outside the ICU), time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge (defined as discharge that was followed by at least a 48-hour period during which the patient was alive and outside the hospital), and 30-day and 90-day survival. Safety end points included the incidence of torsades de pointes and neuroleptic malignant syndrome and the severity of extrapyramidal symptoms, as measured on the modified Simpson–Angus Scale.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptions of sample-size calculations and statistical methods are included in the Supplementary Appendix. We sought to randomly assign 561 patients (187 per trial group), which would provide the trial with at least 80% power to detect a 2-day difference between groups in days alive without delirium or coma, at a twosided significance level of 2.5% (after Bonferroni adjustment for two pairwise comparisons).

We analyzed all data using an intention-to-treat approach and compared the effects of haloperidol, ziprasidone, and placebo with respect to the primary end point using the Kruskal–Wallis test in unadjusted analyses and proportional-odds logistic regression in adjusted analyses. The primary analysis was performed with the use of an adjusted proportional-odds logistic-regression model that examined the effects of an intervention on days alive without delirium or coma, with a two-sided significance level of 2.5% to account for two pairwise comparisons, which were to be analyzed only if the P value for the overall effect across trial groups was significant. There was no plan for adjustment for multiple comparisons of secondary end points, and those results are reported without P values as point estimates with 95% confidence intervals that have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons. A total of 300 of 6100 (5%) potential assessments for delirium or coma were missing; we imputed these individual assessments using polytomous logistic regression that included multiple covariates. After calculating days alive without delirium or coma, we then used complete case analysis for all outcomes (see the Supplementary Appendix). We collected and managed data using REDCap electronic data-capture tools and used R software, version 3.4.4,34 for data management and statistical analyses. R code is available through Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mq38r).

RESULTS

PATIENTS

From December 2011 through August 2017, we screened 20,914 patients, of whom 16,306 (78%) met one or more exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 4608 patients, 3425 (74%) patients or their authorized representatives declined to participate, and 1183 (26%) consented to be assessed further to determine whether they met eligibility criteria. Among those, 46 (4%) met exclusion criteria, and 571 (48%) never had delirium before ICU discharge, leaving 566 patients (48%) who had delirium and met the criteria for random assignment to a trial group. At the time of randomization, 89% of the patients had hypoactive delirium, and 11% had hyperactive delirium. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the trial groups (Table 1).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, Follow-up, and Analysis.

The numbers of patients excluded for each criterion sum to more than the total excluded because some patients met more than one exclusion criterion. ICU denotes intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Trial Population.*

| Characteristic | Placebo (N = 184) |

Haloperidol (N = 192) |

Ziprasidone (N = 190) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 59 (52–67) | 61 (51–69) | 61 (50–69) |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 77 (42) | 84 (44) | 82 (43) |

| Race — no. (%)† | |||

| White | 153 (83) | 163 (85) | 151 (79) |

| Black | 26 (14) | 23 (12) | 27 (14) |

| Multiple races or other race | 5 (3) | 6 (3) | 12 (6) |

| Median short-form IQCODE score (IQR)‡ | 3.1 (3.0–3.3) | 3.0 (3.0–3.2) | 3.1 (3.0–3.3) |

| Median Charlson Comorbidity Index score (IQR)§ | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) |

| Received antipsychotic treatment — no. (%) | |||

| Before admission | 6 (3) | 8 (4) | 11 (6) |

| Between admission and randomization | 18 (10) | 20 (10) | 22 (12) |

| Hyperactive delirium at randomization — no. (%) | 22 (12) | 19 (10) | 16 (8) |

| Hypoactive delirium at randomization — no. (%) | 161 (88) | 172 (90) | 172 (91) |

| Diagnosis at admission — no. (%) | |||

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | 39 (21) | 44 (23) | 35 (18) |

| Sepsis | 35 (19) | 43 (22) | 33 (17) |

| Airway protection | 53 (29) | 46 (24) | 44 (23) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or other pulmonary disorder | 23 (12) | 20 (10) | 28 (15) |

| Surgery | 13 (7) | 13 (7) | 23 (12) |

| Chronic heart failure, myocardial infarction, or arrhythmia | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) |

| Cirrhosis or liver failure | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Seizures or neurologic disease | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 8 (4) | 13 (7) | 17 (9) |

| Admitted to surgical ICU — no. (%) | 52 (28) | 51 (27) | 55 (29) |

| Median APACHE II score at ICU admission (IQR)¶ | 30 (24–34) | 28.5 (23–34) | 28 (23–34) |

| Median SOFA score at randomization (IQR)‖ | 11 (8–14) | 11 (8–13) | 10 (8–13) |

| Received assisted ventilation before randomization — no. (%) | |||

| Invasive | 170 (92) | 178 (93) | 180 (95) |

| Noninvasive | 5 (3) | 7 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Shock before randomization — no. (%)** | 65 (35) | 58 (30) | 64 (34) |

| Median no. of days from ICU admission to randomization (IQR) | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) | 2.4 (1.5–3.4) | 2.5 (1.5–3.4) |

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the trial groups. ICU denotes intensive care unit, and IQR interquartile range. Percentages may not total to 100 because of rounding.

Race was reported by the patients or determined by the treating physicians.

The short-form Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) was used to determine preexisting dementia; scores range from 1.0 to 5.0, with higher scores indicating more severe cognitive impairment.

Scores on the Charlson Comorbidity Index range from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of death from a coexisting illness.

The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II is a prediction tool for death and measures severity of disease in the ICU; scores range from 0 to 71, with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness.

The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) is a tool to track organ failure in the ICU; scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness.

Shock was defined as treatment of hypotension with vasopressors or an intraaortic balloon pump.

INTERVENTIONS AND CONCURRENT SEDATING MEDICATIONS

The duration and number of doses of a trial drug or placebo received by the patients during the 14-day intervention period were similar in the three groups (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). All but two patients received at least one dose of a trial drug or placebo. The median duration of exposure to a trial drug or placebo was 4 days (interquartile range, 3 to 7), and the mean (±SD) daily doses of haloperidol and ziprasidone administered were 11.0±4.8 mg and 20.0±9.4 mg, respectively.

Approximately half the patients had a trial drug or placebo temporarily withheld at least once during the trial (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix); the frequency of withholding an intervention did not differ significantly between the trial groups. A trial drug or placebo was permanently discontinued at a similar frequency and for similar reasons in the three trial groups.

A total of 118 patients (21%) received an open-label antipsychotic medication during the trial; the frequency of use and doses administered were similar in the three trial groups (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The median cumulative dose of a nontrial, open-label antipsychotic medication in haloperidol equivalents was 5 mg (interquartile range, 2 to 12) over a median of 2 days (interquartile range, 1 to 5). Approximately 90% of patients received one or more doses of analgesics or sedatives, and the duration of exposure to these agents was similar in the three trial groups (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The daily rate of adherence to each of the five components of the ABCDE bundle was greater than 88% in all three trial groups (see the Supplementary Appendix).

EFFICACY END POINTS

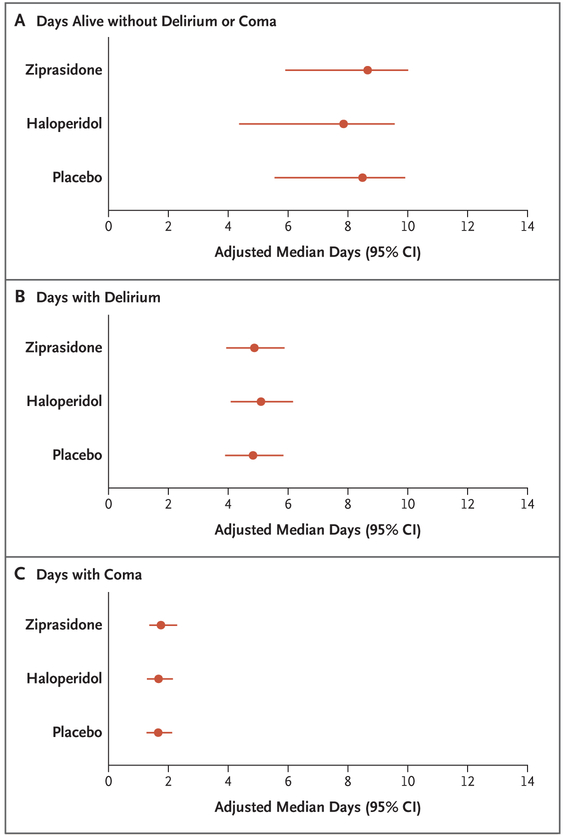

The adjusted median number of days alive without delirium or coma was 8.5 (95% CI, 5.6 to 9.9) in the placebo group, as compared with 7.9 (95% CI, 4.4 to 9.6) in the haloperidol group and 8.7 (95% CI, 5.9 to 10.0) in the ziprasidone group (Fig. 2). The P value for the overall effect across trial groups was 0.26, and therefore, as prespecified in the protocol, no P values were calculated for pairwise comparisons. In adjusted and unadjusted analyses of the active trial-drug groups, as compared with the placebo group, the 95% confidence intervals for the odds ratios included unity for days with delirium and for days with coma during the 14-day intervention period (Fig. 2 and Table 2). In analyses of 30-day and 90-day survival as well as time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, and hospital discharge, the 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratios of the effects of haloperidol and ziprasidone, as compared with placebo, included unity (Table 2 and Fig. 3; and see the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 2. Effects of Haloperidol, Ziprasidone, and Placebo on Days Alive without Delirium or Coma, Days with Delirium, and Days with Coma.

In analyses that were adjusted for age, preexisting cognitive impairment, Clinical Frailty Score and Charlson Comorbidity Index score at baseline, and modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score and Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale score at randomization, there were no significant differences between the trial groups with respect to the primary end point (days alive without delirium or coma) and with respect to the secondary end points of mental status (durations of delirium and coma).

Table 2.

Efficacy End Points.*

| End Point | Placebo (N = 184) |

Haloperidol (N = 192) |

Ziprasidone (N = 190) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days alive without delirium or coma | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 7 (0–11) | 8 (0–11) | 8 (2–11) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 1.04 (0.73–1.48) |

| Days with delirium | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–6) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) | 1.02 (0.69–1.51) |

| Days with hyperactive delirium | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 1.18 (0.86–1.61) | 1.09 (0.70–1.70) |

| Days with hypoactive delirium | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 3 (2–8) | 4 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) |

| Adjusted odds ratio | Reference | 1.10 (0.81–1.48) | 1.00 (0.68–1.47) |

| Days with coma | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 1.01 (0.74–1.39) | 1.11 (0.77–1.61) |

| Days to freedom from mechanical ventilation | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–6) | 3 (2–5) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) |

| Days to ICU discharge | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 5 (3–14) | 5 (3–13) | 6 (3–10) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) | 1.02 (0.88–1.17) |

| ICU readmission | |||

| Unadjusted no. of patients (%) | 23 (12) | 27 (14) | 18 (9) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 1.13 (0.62–2.09) | 0.73 (0.49–1.10) |

| Days to hospital discharge | |||

| Unadjusted median no. of days (IQR) | 13 (8–23) | 13 (8–22) | 12 (8–21) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio | Reference | 1.03 (0.85–1.23) | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) |

| Death at 30 days | |||

| Unadjusted no. of patients (%) | 50 (27) | 50 (26) | 53 (28) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 1.03 (0.73–1.46) | 1.07 (0.77–1.47) |

| Death at 90 days | |||

| Unadjusted no. of patients (%) | 63 (34) | 73 (38) | 65 (34) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference | 1.17 (0.99–1.40) | 1.02 (0.79–1.30) |

The P value for the overall effect across groups was 0.26; therefore, no pairwise P values were calculated. All time-to-event results are reported for the patients who had the outcome of interest. Results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons of secondary end points but were adjusted for age, baseline Charlson Comorbidity Index score, baseline Clinical Frailty Score, baseline cognitive impairment (as determined according to the short form of the IQCODE), modified SOFA score at randomization, and Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale score at randomization.

Figure 3. Effects of Haloperidol, Ziprasidone, and Placebo on 90-Day Survival.

Shown are Kaplan–Meier curves of the probability of survival. In analyses that were adjusted for age, preexisting cognitive impairment, Clinical Frailty Score and Charlson Comorbidity Index score at baseline, and modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score and Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale score at randomization, there were no significant differences in 90-day survival between the trial groups. Results have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons. The shading indicates the 95% confidence intervals.

The results regarding the heterogeneity of effect across interventions are available in the Supplementary Appendix. The effects of antipsychotic medications on durations of delirium, coma, and hypoactive delirium, as well as on 90-day survival, differed according to age, but the trial may not have been adequately powered to draw conclusions about these subgroups. There were no significant interactions between the severity of illness at randomization and the effects of antipsychotic medications on outcomes of mental status.

SAFETY END POINTS

The frequency of excessive sedation, the most common safety end point, did not differ significantly between the trial groups (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Prolongation of the corrected QT interval was more common in the ziprasidone group than in the haloperidol group or placebo group. Torsades de pointes developed in two patients in the haloperidol group during the intervention period, but neither patient had received haloperidol during the 4 days immediately preceding the arrhythmia. One patient in the haloperidol group had the trial drug withheld because of suspected neuroleptic malignant syndrome, but this diagnosis was subsequently ruled out. Three patients (one in each group) had a trial drug or placebo withheld because of extrapyramidal symptoms, and one patient in the haloperidol group had the trial drug withheld specifically because of dystonia.

DISCUSSION

For more than 40 years, intravenous antipsychotic medications have been used to treat delirium in hospitalized patients.16,35-39 In an international survey of 1521 intensivists, 65% reported that they treat delirium in the ICU with haloperidol and 53% reported that they treat delirium with atypical antipsychotic medications.16 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous antipsychotic medications for the treatment of delirium in the ICU, there was no evidence that either haloperidol or ziprasidone led to a shorter duration of delirium and coma. Patients who received treatment with up to 20 mg of haloperidol per day or up to 40 mg of ziprasidone per day and those who received placebo had similar outcomes, including survival and lengths of stay in the ICU and hospital.

The results of our trial were similar to those of two earlier placebo-controlled trials that examined haloperidol for delirium in smaller numbers of patients in the ICU. In the Modifying the Incidence of Delirium (MIND) trial,18 101 patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the ICU were randomly assigned to receive enteral haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo; the results showed no significant differences in days alive without delirium or coma. In the Haloperidol Effectiveness in ICU Delirium (Hope-ICU) trial,19 142 patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the ICU were randomly assigned to receive intravenous haloperidol or placebo; the results also showed no effect on days alive without delirium or coma, although there were fewer days with agitated delirium in patients who received haloperidol.

One possible reason that we found no evidence that the use of haloperidol or ziprasidone resulted in a fewer days with delirium or coma than placebo is that the mechanism of brain dysfunction that is considered to be targeted by antipsychotic medications — increased dopamine signaling — may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of delirium during critical illness. Another possible reason is that heterogeneous mechanisms may be responsible for delirium in critically ill patients. Sedation with γ-aminobutyric acid agonists, for example, is a common risk factor for delirium during critical illness.40 In the current trial, approximately 90% of the patients received one or more doses of sedatives or analgesics, and the doses of sedatives and off-trial antipsychotic medications and the durations of exposures to those agents were similar in all trial groups. Most patients in the trial had hypoactive delirium, which made it difficult to estimate the effect of antipsychotic medications on hyperactive delirium. Nevertheless, the delirium-assessment tool that was used to determine the trial outcomes takes into account integrated aspects of the delirium syndrome and supports the conclusion that the trial drugs had no effect on the duration of delirium as compared with placebo.

Strengths of this trial include a large sample size, broad inclusion criteria to enhance generalizability, delivery of the trial drug or placebo in a double-blinded fashion, and use of validated instruments administered by trained personnel. Limitations of this investigation should also be considered. The possibility of an effect size of less than a 2-day difference in days alive without delirium or coma cannot be excluded, because the trial was powered to detect a 2-day difference between groups with respect to the primary end point. We studied two specific antipsychotic medications, and our results do not exclude the possibility that other antipsychotic medications could reduce the duration of delirium.20 We did not limit our enrollment to a homogeneous group of patients who had delirium in the ICU, and our findings allow for the possibility that some patients (e.g., nonintubated patients with hyperactive delirium describing delusions and hallucinations, those with alcohol withdrawal, or those with another delirium phenotype2) may benefit from antipsychotic treatment. The 20-mg dose of haloperidol that we used in the trial is considered to be high,36-38 and yet we cannot exclude a potential benefit from higher doses.39 In keeping with the literature on haloperidol use,41 which indicates that a dose of haloperidol higher than 25 mg per day has a deleterious effect on cognition, we chose a dose that would avoid these adverse effects. Finally, although this trial was powered to detect clinically meaningful between-group differences with respect to the primary end point, it lacked sufficient power to assess whether haloperidol and ziprasidone would significantly increase the risk of infrequent complications such as torsades de pointes.42

In conclusion, in this large, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, we found no evidence that the use of haloperidol (up to 20 mg daily) or ziprasidone (up 40 mg daily) had an effect on the duration of delirium among patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in the ICU.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (AG035117 and TR000445) from the National Institutes of Health and by the Department of Veterans Affairs Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center.

Footnotes

A complete list of the Modifying the Impact of ICU-Associated Neurological Dysfunction-USA (MIND-USA) Investigators is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

T.D. Girard, Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness Center, Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh

M.C. Exline, Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine Division, Department of Medicine, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio

S.S. Carson, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

C.L. Hough, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle

P. Rock, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore

M.N. Gong, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, New York

I.S. Douglas, Division of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver

A. Malhotra, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Diego, San Diego

R.L. Owens, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Diego, San Diego

D.J. Feinstein, Cone Health System, Greensboro, North Carolina

B. Khan, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Sleep, and Occupational Medicine, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis

M.A. Pisani, Section of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

R.C. Hyzy, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor

G.A. Schmidt, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Occupational Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City

W.D. Schweickert, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia

R.D. Hite, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio

D.L. Bowton, Section on Critical Care, Department of Anesthesiology, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

A.L. Masica, Center for Clinical Effectiveness, Baylor Scott and White Health, Dallas

J.L. Thompson, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Department of Medicine, the Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

R. Chandrasekhar, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Center for Health Services Research; Department of Medicine, the Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

B.T. Pun, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

C. Strength, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Center for Health Services Research; Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

L.M. Boehm, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

J.C. Jackson, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Center for Health Services Research; Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine; Department of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville; Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville

P.P. Pandharipande, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Division of Anesthesiology Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville; Anesthesia Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville

N.E. Brummel, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Center for Health Services Research; Center for Quality Aging; Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

C.G. Hughes, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Division of Anesthesiology Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville; Anesthesia Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville

M.B. Patel, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, Department of Surgery, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville; Surgical Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville

J.L. Stollings, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Department of Pharmaceutical Services, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

G.R. Bernard, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville

R.S. Dittus, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Center for Health Services Research; Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville; Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville

E.W. Ely, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center; Center for Health Services Research; Center for Quality Aging; Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville; Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville.

REFERENCES

- 1.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018;46(9):e825–e873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girard TD, Thompson JL, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:213–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2004;291:1753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180: 1092–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein Klouwenberg PM, Zaal IJ, Spitoni C, et al. The attributable mortality of delirium in critically ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2014;349:g6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:1892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shehabi Y, Riker RR, Bokesch PM, Wisemandle W, Shintani A, Ely EW. Delirium duration and mortality in lightly sedated, mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care Med 2010;38: 2311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasilevskis EE, Chandrasekhar R, Holtze CH, et al. The cost of ICU delirium and coma in the intensive care unit patient. Med Care 2018;56:890–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1306–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:30–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolters AE, van Dijk D, Pasma W, et al. Long-term outcome of delirium during intensive care unit stay in survivors of critical illness: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2014;18:R125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:1297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, et al. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40:370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ely EW, Stephens RK, Jackson JC, et al. Current opinions regarding the importance, diagnosis, and management of delirium in the intensive care unit: a survey of 912 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med 2004;32:106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel RP, Gambrell M, Speroff T, et al. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med 2009;37:825–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morandi A, Piva S, Ely EW, et al. Worldwide survey of the “Assessing pain, Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, Choice of drugs, Delirium monitoring/management, Early exercise/mobility, and Family empowerment” (ABCDEF) bundle. Crit Care Med 2017;45(11):e1111–e1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mac Sweeney R, Barber V, Page V, et al. A national survey of the management of delirium in UK intensive care units. QJM 2010;103:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2010;38: 428–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page VJ, Ely EW, Gates S, et al. Effect of intravenous haloperidol on the duration of delirium and coma in critically ill patients (Hope-ICU): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devlin JW, Roberts RJ, Fong JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med 2010;38:419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;6:CD005594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med 1994;24: 145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA 2001; 286:2703–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001;29:1370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA 2003;289:2983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson JF, Pun BT, Dittus RS, et al. Delirium and its motoric subtypes: a study of 614 critically ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970;212:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med 2017;45:321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balas MC, Burke WJ, Gannon D, et al. Implementing the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle into everyday care: opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned for implementing the ICU Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Guidelines. Crit Care Med 2013;41: Suppl 1:S116–S127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnes-Daly MA, Phillips G, Ely EW. Improving hospital survival and reducing brain dysfunction at seven California community hospitals: implementing PAD guidelines via the ABCDEF bundle in 6,064 patients. Crit Care Med 2017;45:171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med 2018. October 19 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dudley DL, Rowlett DB, Loebel PJ. Emergency use of intravenous haloperidol. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1979;1:240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Settle EC Jr, Ayd FJ Jr. Haloperidol: a quarter century of experience. J Clin Psychiatry 1983;44:440–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tesar GE, Stern TA. Evaluation and treatment of agitation in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 1986;1:137–48. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tesar GE, Murray GB, Cassem NH. Use of high-dose intravenous haloperidol in the treatment of agitated cardiac patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1985;5: 344–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riker RR, Fraser GL, Cox PM. Continuous infusion of haloperidol controls agitation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1994;22:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shehabi Y, Bellomo R, Kadiman S, et al. Sedation intensity in the first 48 hours of mechanical ventilation and 180-day mortality: a multinational prospective longitudinal cohort study. Crit Care Med 2018;46:850–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodward ND, Purdon SE, Meltzer HY, Zald DH. A meta-analysis of cognitive change with haloperidol in clinical trials of atypical antipsychotics: dose effects and comparison to practice effects. Schizophr Res 2007;89:211–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 2009;360:225–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.