Abstract

Purpose:

To assess treatment outcomes in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)-associated uveitis and relapse rates upon discontinuation of immunomodulatory therapy (IMT).

Methods:

Medical records of patients with JIA-associated uveitis seen at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the F.I. Proctor Foundation uveitis clinics from 9/14/88 to 1/5/11 were reviewed. The main outcome was time to relapse after attempting to discontinue IMT.

Results:

Of 66 patients with JIA-associated uveitis, 51(77%) received IMT either as sole or combination therapy. 41/51 (80%) of patients achieved corticosteroid-sparing control. Attempts were made to discontinue treatment in 19/51 (37%) patients. 13/19 (68%) of those attempting to discontinue IMT relapsed, with a median time to relapse of 288 days from the time of attempted taper/discontinuation (IQR: 108–338).

Conclusions:

Corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation was achieved in the majority of patients; however, attempts to stop IMT were often unsuccessful. Close follow-up of patients after discontinuation of therapy is warranted.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an arthritis of unknown etiology, which begins before 16 years of age and persists at least 6 weeks.1 It is a major cause of ocular inflammation in children, with an incidence of 4.9 to 6.9 per 100,000 person-years, and a prevalence of 13 to 30 per 100,000 people.2 JIA-associated uveitis is associated with ocular complications such as cataract, band keratopathy, ocular hypertension, hypotony, macular edema, optic nerve edema, and vision loss.3

Although topical and oral corticosteroids are still the mainstay of initial treatment for JIA-associated uveitis, the chronic nature of inflammation combined with the detrimental effects of long-term corticosteroid use often require that alternative treatments be considered.4,5 Corticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapies (IMT) such as antimetabolites or TNF-α inhibitors are commonly used.6,7 However, limited data are available regarding the ability to successfully discontinue treatment when remission of JIA-associated uveitis is presumed. One study showed that 8/13 (69%) of patients with JIA-associated uveitis relapsed after discontinuation of methotrexate.8 Studies of TNF-α inhibitors are lacking and are of particular interest given the uncertainty about the long-term safety of these drugs in the pediatric population.9,10 We therefore assessed treatment outcomes in JIA-associated uveitis, relapse rates upon discontinuation of therapy, and predictors of relapse in patients attempting to discontinue TNF-α inhibitors.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of medical records of patients with JIA-associated uveitis seen at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Francis I. Proctor Foundation at the University of California, San Francisco uveitis clinics from September 14, 1988 to January 5, 2011. JIA diagnoses were made by pediatric rheumatologists, and uveitis diagnoses were made by ophthalmologists specializing in uveitis. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of California, San Francisco for all aspects of this study involving retrospective review of patient data. All work was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Information collected from the medical records included patient demographics, clinical characteristics, level of ocular inflammation throughout the treatment course, IMT and doses prescribed, and relapse after withdrawal of IMT. In both uveitis practices, duration of treatment with IMT was determined in collaboration with the pediatric rheumatologist. Treatment was withdrawn after presumed remission following a period of inactive uveitis or due to other reasons including adverse events, lack of systemic efficacy, pregnancy, and cost. Corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation was defined as ≤0.5+ anterior chamber cells, ≤0.5+ vitreous haze, a prednisone dose ≤10 mg daily, and prednisolone acetate dose ≤ 3 times/day. Relapse of uveitis after IMT withdrawal was defined as the presence of 1+ or more cells in the anterior chamber or 1+ or more vitreous haze in patients who had inactive uveitis at the time discontinuation was attempted.

The main outcome was time to relapse, defined as the time from the date of initiation of the treatment taper or treatment discontinuation (if no taper) until the date of relapse. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to analyze relapse over time and the log-rank test was applied to test the differences in relapse among individuals discontinuing TNF-α inhibitors due to presumed remission and individuals stopping due to other reasons. Bivariable Cox regression models were applied to evaluate the association between various predictors of relapse and time to relapse among individuals stopping TNF- α inhibitors. Predictors evaluated include age at withdrawal, sex, time on biologic treatment, duration of corticosteroid-sparing control, and time from uveitis diagnosis to start of biologic treatment. All statistical tests utilized a 0.05 level of significance. Due to a small sample size, all statistically significant predictors were tested further using permutation tests. Statistical analyses were performed by using Stata 10.1 (Stata Corp College Station, TX).

Results

Sixty-six patients were identified with JIA-associated uveitis from the two centers. Median follow-up time was 854 days (interquartile range (IQR) 189–2280 days). The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with JIA-associated uveitis (n=66) are described in Table 1. Of note, 59 (89%) were female, and 63 (95%) had a chronic uveitis course. At presentation, 24 (36%) complained of reduced vision, but a significant minority, 17 (26%), had no symptoms. Reasons for referral to an ophthalmologist included being referred by another health care provider (24, 36%), having a diagnosis of JIA (16, 24%), and eye symptoms (11, 17%). Anterior chamber inflammation at presentation is described in Table 2. Prior to or at presentation, patients had been on various therapies, including 52 (79%) on topical corticosteroids, 24 (36%) on methotrexate, 14 (21%) on oral corticosteroid, and 14 (21%) on oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Fewer than 10% had been treated with TNF-α inhibitors prior to or at presentation. The most common complications at presentation, which may have occurred in either eye, included cataract in 35 patients (53%), posterior synechiae in 33 (50%), band keratopathy in 26 (39%), keratic precipitates in 19 (29%), and glaucoma in 10 (15%).

Table 1:

Characteristics of Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) Associated Uveitis (n=66 patients)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Female | 59 (89%) |

| Median age at JIA onset | 2 years (IQRa: 1–6.25 years) |

| Median age at uveitis onset | 4 years (IQRa: 2–6 years) |

| Race | |

| White | 53 (80%) |

| Black | 6 (9%) |

| Indian Subcontinent | 3 (5%) |

| Asian | 1 (2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 14 (21%) |

| Type of JIA | |

| Oligoarticular | 44 (67%) |

| Polyarticular | 9 (14%) |

| Type of uveitis | |

| Anterior | 57 (86%) |

| Anterior and intermediate | 6 (9%) |

| Bilateral uveitis | 53 (80%) |

| Chronic uveitis course | 63 (95%) |

| Median visual acuity at presentation | |

| Right eye | 20/30 (IQRa: 20/20 – 20/50) |

| Left eye | 20/25 (IQRa: 20/20 – 20/40) |

IQR = interquartile range

Table 2:

Anterior Chamber Inflammation Activity Grade at Presentation

| Left eye n (%) | Right eye n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 (15) | 11 (18) |

| 0.5+ | 14 (26) | 13 (21) |

| 1+ | 11 (21) | 10 (16) |

| 2+ | 10 (19) | 7 (12) |

| 3+ | 7 (13) | 14 (23) |

| 4+ | 1 (2) | 5 (8) |

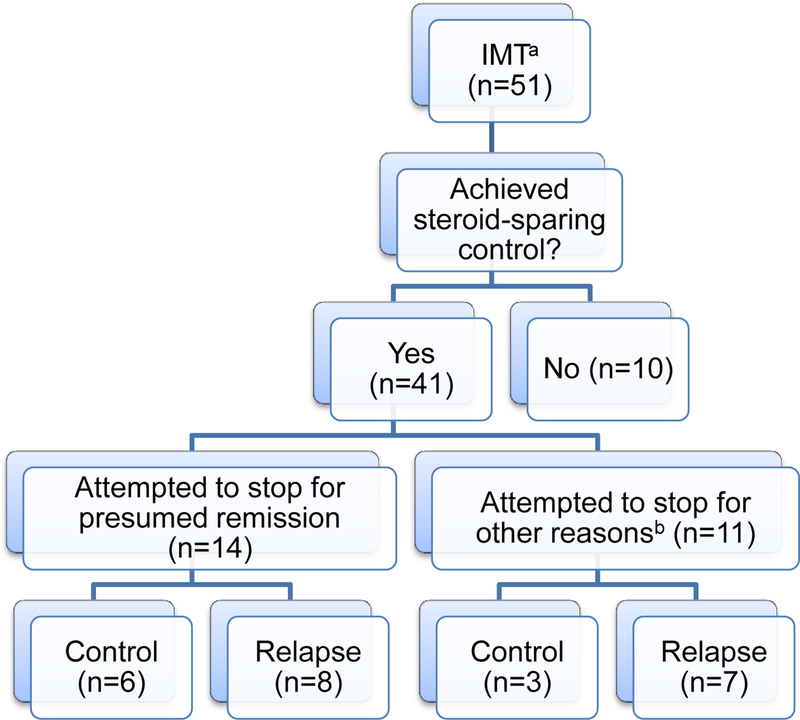

During follow-up at our uveitis clinics, 51 patients (77%) received corticosteroid-sparing IMT either as sole or part of combination therapy. The most common therapies received were methotrexate in 44 patients (86%), adalimumab in 13 (25%), infliximab in 12 (24%), mycophenolate mofetil in 8 (16%), cyclosporine in 6 (12%), and etanercept in 5 (10%). As shown in Figure 1, 41/51 (80%) of patients on corticosteroid-sparing IMT achieved corticosteroid-sparing control. Of note, of the 41 patients achieving corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation, 34 did so while on no oral prednisone. The remaining 7 were on a median dose of 8.75 mg oral prednisone daily (IQR: 3–10). 35 were on topical corticosteroids, with a median dose frequency of 2 drops/day (IQR: 2–3) of prednisolone acetate 1%.

Figure 1: Treatment Overview.

aImmunomodulatory therapy

bOther reasons for stopping include: adverse events (n=6), lack of systemic efficacy (n=2), pregnancy (n=1), cost (n=1), and unknown (n=1).

Table 3 shows the proportion of patients achieving corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation by treatment regimen. A majority of patients achieved corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation. Generally, the proportion of patients achieving corticosteroid-sparing control was higher in those receiving IMT in combination rather than as sole therapy.

Table 3:

Proportion of Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Associated Uveitis Achieving Corticosteroid-sparing Control of Inflammation

| Proportion achieving corticosteroid-sparing control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | IMT alone | % | IMT in combination | % | |

| Methotrexate | 33/42 | 79 | 19/25 | 76 | 14/17 | 82 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 4/7 | 57 | 1/2 | 50 | 3/5 | 60 |

| Cyclosporine | 5/6 | 83 | 1/1 | 100 | 4/5 | 80 |

| Adalimumab (Humira) | 6/14 | 43 | 1/6 | 17 | 5/8 | 63 |

| Etanercept (Enbrel) | 2/3 | 67 | 2/2 | 100 | 0/1 | 0 |

| Infliximab (Remicade) | 10/11 | 91 | 3/3 | 100 | 7/8 | 88 |

Attempts were made to discontinue treatment in 19/51 (37%) patients on IMT. The median doses of IMT at the start of attempted taper were: 20 mg/week for methotrexate, 2 g/day for mycophenolate mofetil, 200 mg/day for cyclosporine, 5 mg/kg/6weeks for infliximab, and 40 mg/2weeks for adalimumab. 14/19 (74%) discontinued treatment due to presumed remission; 11/19 (58%) discontinued treatment after achieving corticosteroid-sparing control, but for reasons other than presumed remission. Other reasons for stopping included adverse events (n=6), lack of systemic efficacy (n=2), pregnancy (n=1), cost (n=1), and unknown (n=1). The total number of reasons for stopping treatment is greater than the number of patients since patients on combination therapy could stop each drug for different reasons. Table 4 shows the relapse rates among those attempting to discontinue treatment. Of note, 13/19 (68%) of those attempting to discontinue IMT relapsed, with a median time to relapse of 288 days from the time of start of attempted taper (IQR: 108–338). 9/11 (82%) of those attempting to discontinue TNF-α inhibitors relapsed. Of note, 5/13 (38%) of those who relapsed after attempting to discontinue IMT were in the process of tapering when they relapsed and had not completely stopped therapy. For those on TNF-α inhibitors, the median time on therapy was 497 days and the median time of corticosteroid-sparing control was 300 days. However, this varied depending on the reason for stopping therapy, such that patients stopping for presumed remission had a median time on therapy of 396 days versus 512 days for those stopping for other reasons. Similarly, the time of corticosteroid-sparing control was 300 days for those tapering for presumed remission versus 276 days for those stopping for other reasons.

Table 4:

Relapse of Inflammation in Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Associated Uveitis Attempting to Stop Immunomodulatory Therapy

| IMT | No. attempting stop | No. relapsing | % relapse | Median time to relapse, (days) | Time to relapse, (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 19 | 13 | 68 | 288 | 108–338 |

| Methotrexate | 12a | 7 | 58 | 336 | 329–636 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2b | 0 | 0 | --- | --- |

| Cyclosporine | 4c | 1 | 25 | 213 | --- |

| Etanercept (Enbrel) | 1d | 0 | 0 | --- | --- |

| Adalimumab (Humira) | 2e | 1 | 50 | 344 | --- |

| Infliximab (Remicade) | 8f | 7 | 88 | 91 | 59–118 |

3 were combination therapies with mycophenolate, adalimumab, and cyclosporine

1 was on combination with infliximab.

3 were on combination with mycophenolate; methotrexate; and methotrexate and infliximab

0 were on combination therapy

1 was on combination with methotrexate

6 were on combination with methotrexate (4) and mycophenolate (2)

None of the patients had any ocular surgeries in the time period between attempting to taper or discontinue immunosuppressive therapy and when uveitis relapse occurred. Some patients did have surgeries while on immunosuppressive therapy, but they achieved uveitis quiescence prior to attempting to stop therapy.

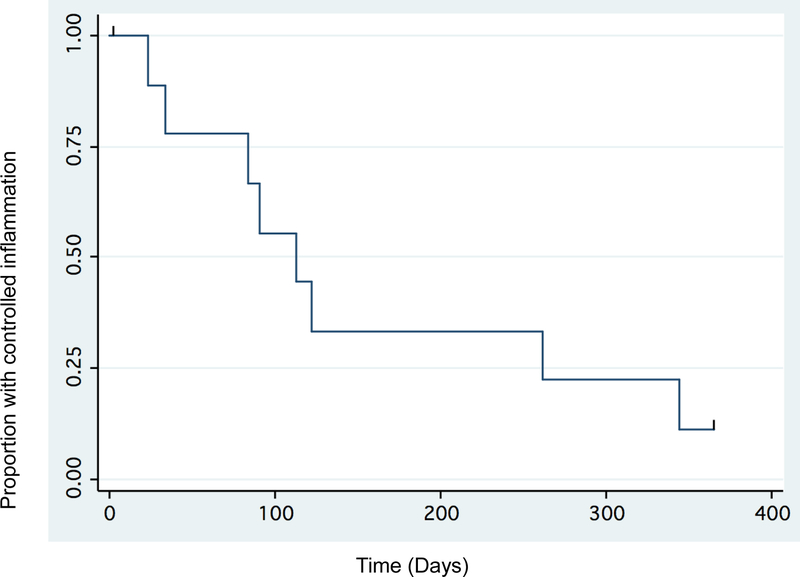

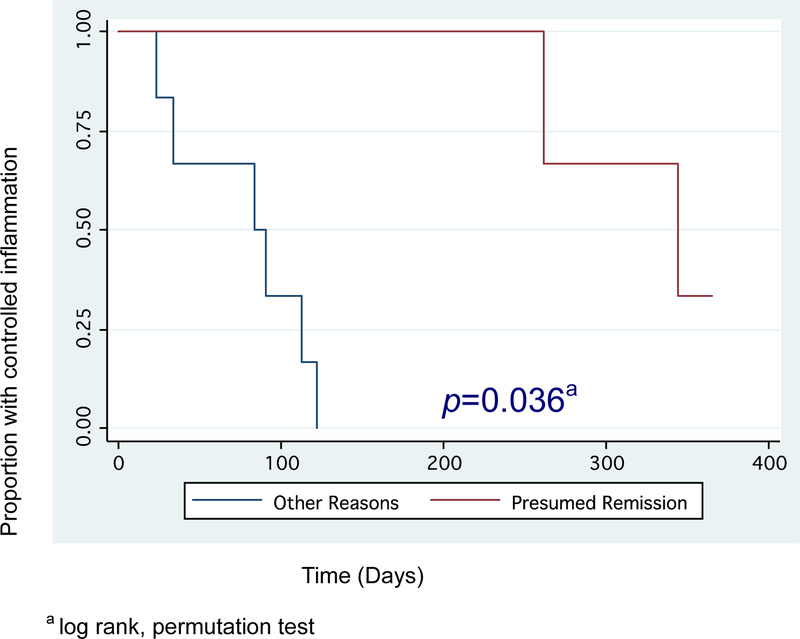

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for the discontinuation of TNF-α inhibitors, and Figure 3 shows the analysis with a log rank permutation test used to compare relapse rates in those tapering TNF-α inhibitors due to presumed remission and those stopping due to other reasons. Those who attempted to taper for presumed remission had a longer time to relapse and a lower proportion of relapse compared to those who stopped for other reasons (p=0.036).

Figure 2:

Time to relapse after attempting to taper/discontinue TNF-α inhibitors

Figure 3:

A comparison of time to relapse after tapering/stopping TNF-α inhibitors for presumed remission versus other reasons

As shown in Table 5, Cox proportional hazard regression used to identify possible predictors of relapse in those attempting to stop TNF-α inhibitors did not reveal significant differences in age at withdrawal, sex, time on biologic treatment, duration of corticosteroid-sparing control, and time from uveitis diagnosis to start of biologic treatment.

Table 5:

Predictors of Relapse after Attempting to Stop TNF-α inhibitors

| Predictor | Hazard Ratio | CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at withdrawal | 1.06 | 0.97, 1.15 | 0.19 |

| Female | 1.42 | 0.17, 12.18 | 0.75 |

| Time on biologic ≥ 486 daysa | 1.63 | 0.40, 6.63 | 0.50 |

| Time from corticosteroid-sparing control to taper or stop date (per 30-day increment) | 1.01 | 0.94, 1.09 | 0.71 |

| Time from uveitis diagnosis to start of biologic ≥ 1765 daysa | 0.63 | 0.14, 2.91 | 0.56 |

These predictors were evaluated in a dichotomous manner based on their median values in our study population.

Discussion

In this multicenter, retrospective cohort study we found that, despite initial success in achieving corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation in JIA-associated uveitis, the discontinuation of IMT, especially of TNF-α inhibitors, was often unsuccessful. Relapse rates upon discontinuation of therapy were found to be high, and the only statistically significant predictor of relapse after discontinuation of TNF-α inhibitors was the reason for discontinuation of therapy.

Although corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation was defined as ≤0.5+ anterior chamber cells, ≤0.5+ vitreous haze, and a prednisone dose ≤10 mg and prednisolone acetate dose ≤ 3 times/day, in reality, most patients were not taking oral prednisone and the median frequency of topical corticosteroids was 2 times a day.

Prior studies of uveitis patients attempting to discontinue TNF-α inhibitors are limited, especially for JIA-associated uveitis. A retrospective cohort study showed that of 18 uveitis patients attempting to discontinue infliximab, 11 (61%) relapsed after a median of 603 days; however, the subset of 4 JIA-associated uveitis patients had a shorter time to relapse of 77 days (p = 0.002).11 By comparison, the observed time to relapse after the start of tapering of therapy in our study seems high. However, this may be attributable to the gradual tapering of IMT which was the norm in patients in this study. Both of the uveitis centers participating in this study generally taper infliximab over several months when attempting to discontinue rather than stopping abruptly. This is done by lowering the dose and/or increasing the duration between infusions. Given the high rate of relapse and the high percentage of those relapsing during taper, we recommend tapering rather than abrupt discontinuation so that recurrence of inflammation can be caught early. In fact, 38% of patients who relapsed did so during the taper rather than after the IMT was completely stopped.

Retrospective studies have also explored the discontinuation of TNF-α inhibitors in other types of uveitis, as well as for systemic diseases such as JIA, and rheumatoid arthritis. A retrospective case series showed that 13/23 (57%) of patients with recurrent Behçet’s uveoretinitis treated with infliximab experienced relapse while still on therapy, most commonly after 6 months of treatment when infusions were less frequently administered.12 Another retrospective study found a relapse rate of 2/4 (50%) among patients with posterior uveitis associated with Behçet’s disease who achieved remission of ocular inflammation on infliximab for a minimum of six months and subsequently stopped therapy.13 Additionally, a large retrospective study found that 56/171 (33%) of JIA patients maintained clinical remission of joint disease after 12 months off anti-TNF-α therapy,14 and a large prospective study evaluating relapse rates after discontinuation of TNF-α therapy in rheumatoid arthritis found that 56/102 (55%) of patients maintained remission at 24 months.15 More research is needed to characterize the potential for treatment withdrawal of TNF-α inhibitors in patients with JIA-associated uveitis.

The issue of discontinuing TNF-α inhibitors is particularly relevant given FDA warnings concerning a potentially increased risk of lymphoma among children taking TNF-α inhibitors,10 and some studies suggesting a possible increased risk of cancer as well as increased overall- and cancer-related mortality.16–18 Furthermore, anti-TNF-α therapy is associated with significant expense, inconvenient administration, and risk of opportunistic infection. Prospective evaluation of the effect of discontinuing anti-TNF-α therapy in JIA-associated uveitis patients and determining risk factors for relapse is a crucial step towards minimizing childhood exposure to the potentially dangerous long-term effects of these treatments.

Although not a study of TNF-α inhibitors, one retrospective case series of 22 patients with JIA-associated uveitis treated with methotrexate found that 8/13 (69%) relapsed after discontinuation of IMT. This high relapse rate is similar to ours. However, in contrast to our study, these authors found statistically significant predictors of relapse-free survival after withdrawal of methotrexate, including treatment duration longer than 3 years prior to withdrawal, age greater than 8 years at the time of withdrawal, and inactivity of uveitis of longer than 2 years prior to withdrawal.8

There are limitations to acknowledge. Despite being a multicenter study over a 24-year period, our sample size limits our power to identify significant predictors of relapse in patients with JIA-associated uveitis attempting to discontinue IMT, and specifically, anti-TNF-α therapy. We hope that our study will lead to additional studies, both larger retrospective studies and prospective studies, designed to clarify treatment dilemmas such as whether to discontinue treatment in cases of presumed remission or to accept the risks of continuing therapy. An additional limitation of our study is that reasons for withdrawal of IMT are not standardized, and there is variability in dosing and tapering practices based on physician and patient preferences. Many of the patients in this study were on concomitant low dose topical corticosteroids. Our general practice is to keep the steroid dose stable while the immunosuppressive therapy is being tapered or discontinued, but it is possible that any change in concomitant therapy could affect outcomes. Selection bias is an unavoidable limitation of this retrospective methodology. Greater disease severity could explain why patients who stopped for reasons other than presumed remission had higher relapse rates. This underscores the need for tapering guidelines and a prospective randomized clinical trial to clarify treatment outcomes and identify predictors of relapse upon discontinuation of IMT in patients with JIA-associated uveitis.

In conclusion, corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation was achieved in the majority of our patients; however, attempts to stop IMT were often unsuccessful despite controlled inflammation for over a year. This study points to the need for continued follow-up of patients during attempts to taper and after discontinuation of therapy for presumed remission and the need for further research into predictors for successful discontinuation of systemic IMT in patients with JIA-associated uveitis.

Acknowledgements

Funding/support:. This work was partly supported by a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to UCSF to fund Clinical Research Fellow Dr. Homayounfar. Dr. Enanoria was supported for statistical consulting by That Man May See Foundation, UCSF. The UCSF Department of Ophthalmology is supported by National Eye Institute grant EY06190 and an unrestricted grant from the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation. Dr. Goldstein is supported by unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. The sponsors or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: NRA reports being a consultant for Abbvie and Santen. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The authors have no proprietary interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 2004;31(2):390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory AC, Kempen JH, Daniel E, et al. Risk factors for loss of visual acuity among patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Study. Ophthalmology 2013;120(1):186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorne JE, Woreta F, Kedhar SR, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: incidence of ocular complications and visual acuity loss. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143(5):840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131(5):679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonini G, Cantarini L, Bresci C, et al. Current therapeutic approaches to autoimmune chronic uveitis in children. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9(10):674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rifkin LM, Birnbaum AD, Goldstein DA. TNF Inhibition for Ophthalmic Indications: Current Status and Outlook. BioDrugs 2013;27(4):347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martel JN, Esterberg E, Nagpal A, et al. Infliximab and adalimumab for uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2012;20(1):18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayuso VK, van de Winkel EL, Rothova A, et al. Relapse rate of uveitis post-methotrexate treatment in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151(2):217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) blockers, Azathioprine and/or Mercaptopurine: Update on Reports of Hepatosplenic T-Cell Lymphoma in Adolescents and Young Adults 2011; Available at http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm251443.htm. Accessed November 30, 2013.

- 10.FDA. Cancer Warnings Required for TNF-Alpha Inhibitors 2009; Available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm175803.htm. Accessed November 30, 2013.

- 11.Shakoor A, Esterberg E, Acharya NR. Recurrence of Uveitis after Discontinuation of Infliximab. Ocul Immunol Inflamm doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.812222.2013.07.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada Y, Sugita S, Tanaka H, et al. Timing of recurrent uveitis in patients with Behcet’s disease receiving infliximab treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95(2):205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adan A, Hernandez V, Ortiz S, et al. Effects of infliximab in the treatment of refractory posterior uveitis of Behcet’s disease after withdrawal of infusions. Int Ophthalmol 2010;30(5):577–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baszis K, Garbutt J, Toib D, et al. Clinical outcomes after withdrawal of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a twelve-year experience. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63(10):3163–3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Mimori T, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab after attaining low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: RRR (remission induction by Remicade in RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69(7):1286–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006;295(19):2275–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempen JH, Gangaputra S, Daniel E, et al. Long-term risk of malignancy among patients treated with immunosuppressive agents for ocular inflammation: a critical assessment of the evidence. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146(6):802–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Dunn JP, et al. Overall and cancer related mortality among patients with ocular inflammation treated with immunosuppressive drugs: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]