Abstract

Background: Pressurized aerosol chemotherapy (PAC) is a novel approach to the treatment of surface malignancies. This study aimed to investigate whether PAC is a feasible treatment of early-stage bladder cancer. Materials and Methods: PAC via inserted microcatheter was performed on a fresh urinary bladder in a post-mortem swine model (n=3), creating a pressurized doxorubicin chemoaerosol. Drug penetration of aerosolized doxorubicin at different concentrations (3 mg/50 ml, 9 mg/50 ml and 15 mg/50 ml) and different locations on the mucosa was measured via fluorescence microscopy. Results: Mean endoluminal penetration rates for the urothelium following PAC reached 149±61 μm (using 15 mg/50 ml). Doxorubicin penetration was significantly increased with higher drug concentration (15 vs. 3 mg/50 ml: p<0.01). This study demonstrated the feasibility of PAC for intravesical use. Conclusion: PAC is a feasible minimally-invasive approach to the treatment of early-stage bladder cancer.

Keywords: Pressurized aerosol chemotherapy, PAC, urinary bladder carcinoma, penetration, early-stage cancer, intravesical chemotherapy, PIPAC

Early-stage cancer of the urinary bladder is a common oncological entity and often requires for surgical intervention. Intravesical chemotherapy (IVC) is most commonly applied following local transurethral resection procedures in early-stage urinary bladder carcinoma (1). Previous studies have shown that patients receiving IVC benefit from this combined therapy with mitomycin C (2). Locally applied chemotherapy can penetrate resected areas and eliminate remaining cancer cells following subtotal resection. The principle of locally-applied postoperative chemotherapeutic installations in the bladder has been thoroughly studied (3-5).

New application options are under particular focus as drug penetration into the urothelium barrier remains a major challenge of liquid installations (6). Pressurized aerosol chemotherapy (PAC) is a possible new clinical approach in the treatment of surface carcinomas. PAC is assumed to possess superior qualities in comparison to liquid intraperitoneal chemotherapy applied with conventional catheters (7,8). PAC applications, such as pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) in peritoneal cancer have already shown promising clinical results (9,10). Technical aspects (11), distribution pattern (12-14) and local penetration rates (15,16) of PAC have been analyzed in the setting of intra-abdominal applications. However, to our knowledge, the concept of treating bladder cancer with a chemoaerosol has never been described before.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were performed at the veterinarian surgical laboratories at Wroclaw University, Wroclaw, Poland. PAC was performed on three postmortem swine 10 minutes after death. Experiments were conducted following a previous cardiovascular study on the swine. The consent of the Local Board on Animal Welfare was given (Nr 11/2018/P1). The fresh post-mortem swine cadavers were placed in a supine position and fixed in a stable position at all four extremities. An Olympus PW-205V microcatheter (MC) (Olympus Surgical Technologies Europe, Hamburg, Germany) was used to generate a polydisperse aerosol. The MC consisted of a connecting device, and a high-pressure line connecting the shaft to the nozzle. The nozzle head had a small central opening. PIPAC via MC has been previously described (17).

The MC extended to an injection line which was inserted into the bladder and residual urine was retrieved. For the entire PAC experiment, a constant inflation of the bladder was established at 8 mmHg using an insufflator (Olympus UHI-3 insufflator; Olympus Australia, Notting Hill, Australia) through the inserted MC. About 200-300 ml of air was pumped into the bladder before a leakage was detected at the point of the external urethral orifice (1). PAC as a total of 50 ml doxorubicin solution was manually delivered into the bladder (1) at 23˚C with a 10 ml syringe at a constant flow. A refill syringe was connected to the side of the injecting syringe allowing application of the entire dose without the need to readapt to a new syringe. Swine A was treated with 3 mg doxorubicin dissolved in 50 ml saline solution, swine B with 9 mg doxorubicin dissolved in 50 ml saline solution and swine C with 15 mg doxorubicin dissolved in 50 ml saline solution. After 5 minutes, air and residual liquid were evacuated using the pressure injection line. The MC was then pulled back. All swine were dissected and the urinary bladders were retrieved. Tissue samples from different locations of the bladder were taken. Additionally, samples from the proximal urethra and both ureters were retrieved (at 1 cm from the orifice).

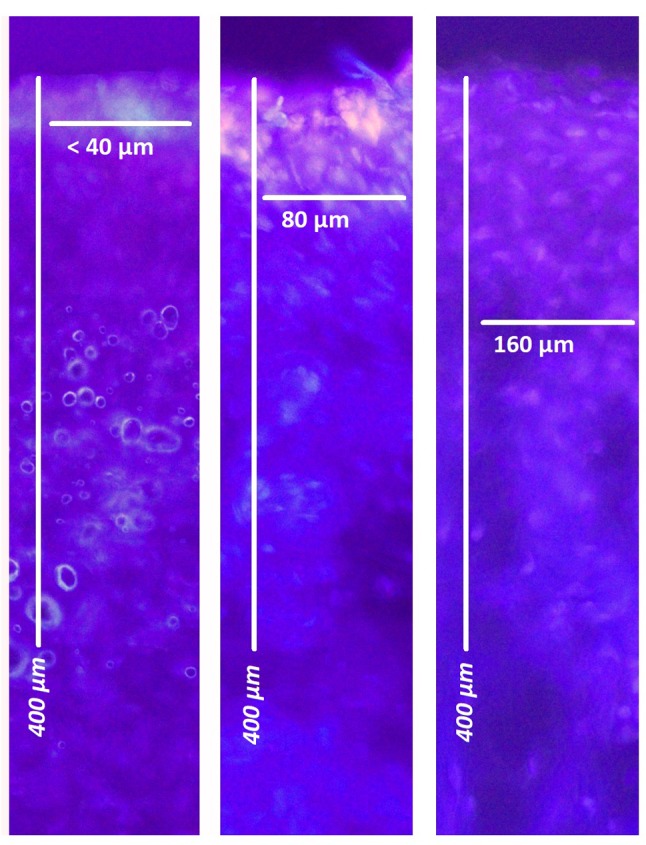

Microscopic analysis. After treatments, tissue samples were rinsed with sterile 0.9% NaCl solution in order to eliminate superficial cytostatics and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections (7 μm) were prepared from the bladder, urethra and ureter samples. Sections were mounted with VectaShield containing 1.5 μg/ml 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Life Technologies Corporation, Eugene, ORUSA) to stain nuclei. The penetration depth of doxorubicin was determined using a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments Europe B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands). The distance between the luminal surface and the innermost positive staining for doxorubicin accumulation was measured and reported in micrometers (2).

Results

In all cases, PAC was performed without complications. MC was easily inserted into the bladder. Residual fluid was removed and air was installed into the bladder. Minor technical problems were caused when inserting the MC into the urethral orifice as the urethral orifice showed little air leakage at higher volumes (>300 ml). No problems were observed during the actual procedure. No air leakage was observed during the injection and the subsequent aerosol phase. No doxorubicin was detected in the ureters or urethra using fluorescence microscopy. However, doxorubicin penetration was detected in the bladder via fluorescence microscopy. Doxorubicin tissue penetration reached 38±13 μm for PAC with 3 mg/50 ml, 54±23 μm for 9 mg/50 ml and 149±61 μm for 15 mg/50 ml. Penetration within the urinary bladder was significantly increased with higher drug dosage (15 mg/50 ml vs. 3 mg/50 ml, p<0.01). No significant inhomogeneity regarding penetration was observed within the bladder tissues.

Discussion

IVC is often applied following local resection procedures in patients with early stages of urinary bladder carcinoma (1,2). The search for less invasive, yet effective bladder cancer therapies has attracted researchers to develop a new drug delivery system whereby drugs may be applied using a urinary catheter (6). The research on IVC systems continues in the treatment of bladder cancer. PAC offers a possible alternative for standard IVC. The antitumor effect currently shown in local applications and fluid installations in bladder cancer is strongly limited by poor penetration (<1 mm) (5). The restricted diffusion of chemoinstallation is attributed to the urothelial layer (4), a high interstitial tumor pressure (18) and the effect of the capillary network, which drains drugs out of the tumor. In contrast to the peritoneal surface, the urothelium is a formidable barrier to chemotherapeutic drugs. Thus, this might explain why penetration is much lower in the urinary bladder than described in standard PIPAC where, at concentrations of doxorubicin at around 3 mg/ml, penetration is up to 600 μm (14). Similar findings regarding the barrier effect for chemosolutions have been observed in experiments with dogs using mitomycin C in liquid installations (4).

These findings underline the importance of the urothelium as a barrier to drug absorption. Yet the function of the urothelial barrier seems to be partially lost in the presence of tumor-bearing tissue. The average mitomycin C concentration in tumor-bearing tissue has been reported to be around 40% higher than the concentration in adjacent normal tissues (p=0.01) (5). Aerosolized chemotherapeutic applications claim superior physical features when compared to liquid installations applied with conventional catheters (7). PAC offers the possibility to treat the remaining malignant tumor cells with higher drug concentrations than those usually applied via IVC. The same overall drug amount for the procedure can be used more effectively as it is applied at a higher concentration. This is achieved by using a smaller application volume with a better distribution than for any liquid installation. Since penetration depth and in-tissue drug concentration directly correlate with the concentration of the applied chemotherapy (19,20), a higher tumor toxicity might be achieved with PAC than in IVC with liquid installations. As the surgical approach of PAC is similar to the placement of a urinary catheter, no severe surgery-related complications or risks are expected. Thus, PAC offers a minimally invasive approach with the option of repetitive treatment, and its possible clinical use should therefore be considered. Furthermore, no reflux of chemo-therapeutic drugs into the ureters was detected.

This study has introduced first data on technical feasibility for PAC in the bladder. However, more experimental studies with regard to safety, optimal volumes, concentrations and in vivo cytotoxic effects should be performed to further investigate this novel approach.

Conclusion

Systemic chemotherapeutic instillation is associated with poor response and drug penetration in the bladder. PAC is a promising new treatment approach for concentrated chemotherapeutic application following local bladder resection. Further studies need to be conducted to optimize PAC for the bladder and evaluate whether PAC can reduce long-term mortality or morbidity.

Conflicts of Interest

This study was funded by institutional funds. The Authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose in regard to this study.

Ethical Approval

All applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local board on animal welfare (Nr 11/2018/P1) where this study was conducted.

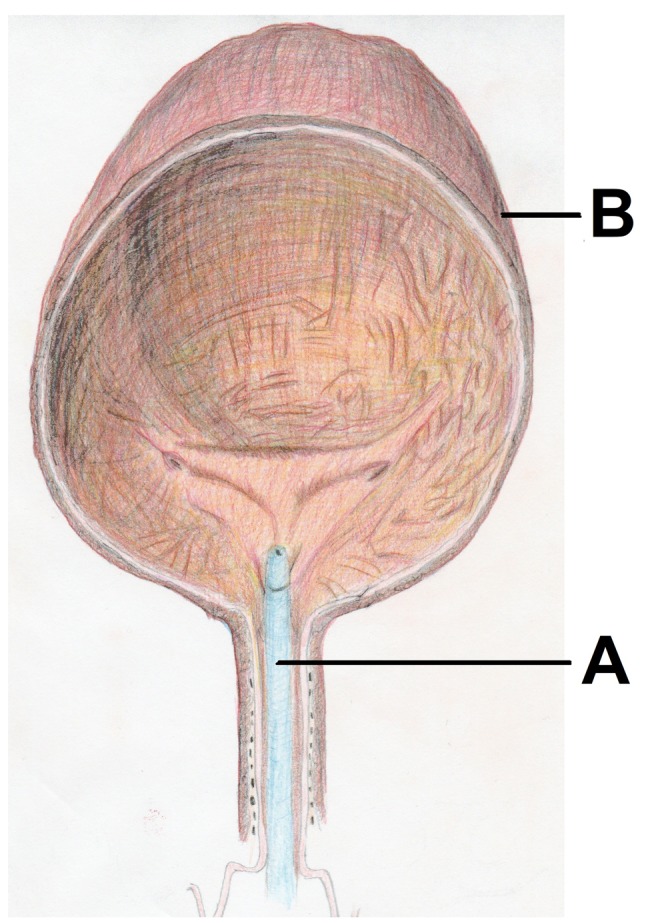

Figure 1. Model of pressurized aerosol chemotherapy with a spray catheter (A) in the urinary bladder (B) of a swine filled with air and receiving aerosolized doxorubicin at 8 mmHg for 30 min.

Figure 2. Fluorescence microscopy: Doxorubicin penetration into the urothelium (red) next to nuclei stained blue with 4’,6-diamidino-2- phenylindole. From left to right: Swine A (3 mg/50 ml), swine B (9 mg/50 ml), swine C (15 mg/50 ml).

References

- 1.Lu DD, Boorjian SA, Raman JD. Intravesical chemotherapy use after radical nephroureterectomy: A national survey of urologic oncologists. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(3):113. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palou-Redorta J, Rouprêt M, Gallagher JR, Heap K, Corbell C, Schwartz B. The use of immediate postoperative instillations of intravesical chemotherapy after TURBT of NMI bladder cancer among European countries. World J Urol. 2014;32(2):525–530. doi: 10.1007/s00345-013-1142-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao X1, Au JL, Badalament RA, Wientjes MG. Bladder tissue uptake of mitomycin C during intravesical therapy is linear with drug concentration in urine. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(1):139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wientjes MG, Dalton JT, Badalament RA, Drago JR, Au JL. Bladder wall penetration of intravesical mitomycin C in dogs. Cancer Res. 1991;51(16):4347–4354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wientjes MG, Badalament RA, Wang RC, Hassan F, Au JL. Penetration of mitomycin C in human bladder. Cancer Res. 1993;53(14):3314–3320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zacchè MM, Srikrishna S, Cardozo L. Novel targeted bladder drug-delivery systems: A review. Res Rep Urol. 2015;23(7):169–178. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S56168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reymond MA, Solass W. Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy Cancer Under Pressure. Boston, DeGruyter. 2014;1:114–127. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solaß W, Kerb R, Mürdter T, Giger-Pabst U, Strumber D, Tempfer C, Zieren J, Schwab M, Reymond MA. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy of peritoneal carcinomatosis using pressurized aerosol as an alternative to liquid solution: First evidence for efficacy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(2):553–559. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3213-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khosrawipour T, Khosrawipour V, Giger-Pabst U. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy in patients suffering from peritoneal carcinomatosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadiradze G, Giger-Pabst U, Zieren J, Strumberg D, Solass W, Reymond MA. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) with low-dose cisplatin and doxorubicin in gastric peritoneal metastasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(2):367–373. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Göhler D, Khosrawipour V, Khosrawipour T, Diaz-Carballo D, Falkenstein TA, Zieren J, Stintz M, Giger-Pabst U. Technical description of the microinjection pump (MIP®) and granulometric characterization of the aerosol applied for pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) Surg Endosc. 2017;31(4):1778–1784. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khosrawipour V, Khosrawipour T, Diaz-Carballo D, Förster E, Zieren J, Giger-Pabst U. Exploring the spatial drug distribution pattern during pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(4):1220–1224. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4954-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khosrawipour V, Mikolajczyk A, Schubert J, Khosrawipour T. Pressurized intra-peritoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) via endoscopical microcatheter system. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(6):3447–3452. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosrawipour V, Khosrawipour T, Falkenstein TA, Diaz-Carballo D, Förster E, Osma A, Adamietz IA, Zieren J, Fakhrian K. Evaluating the effect of Micropump© position, internal pressure and doxorubicin dosage on efficacy of pressurized intra-peritoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) in an ex vivo model. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(9):4595–4600. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khosrawipour V, Bellendorf A, Khosrawipour C, Hedayat-Pour Y, Diaz-Carballo D, Förster E, Mücke R, Kabakci B, Adamietz IA, Fakhrian K. Irradiation does not increase the penetration depth of doxorubicin in normal tissue after pressurized intra-peritoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) in an ex vivo model. In Vivo. 2016;30(5):593–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khosrawipour V, Giger-Pabst U, Khosrawipour T, Pour YH, Diaz-Carballo D, Förster E, Böse-Ribeiro H, Adamietz IA, Zieren J, Fakhrian K. Effect of irradiation on tissue penetration depth of doxorubicin after pressurized intra-peritoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) in a novel ex vivo model. J Cancer. 2016;7(8):910–914. doi: 10.7150/jca.14714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikolajczyk A, Khosrawipour V, Schubert J, Chaudhry H, Pigazzi A, Khosrawipour T. Particle stability during pressurized intra-peritoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) Anticancer Res. 2018;38(8):4645–4649. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain RK. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Sci Am. 1994;271(1):58–65. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0794-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dedrick RL, Myers CE, Bungay PM, DeVita VT Jr. Pharmacokinetic rational for the peritoneal drug administration in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62(1):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flessner MF. The transport barrier in intraperitoneal therapy (review) Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288(3):433–442. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00313.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]