Abstract

Wheat is one of the world’s most important sources of food. However, due to its evolution its genetic base has narrowed, which is severely limiting the ability of breeders to develop new higher yielding varieties that can adapt to the changing environment. In contrast to wheat, its wild relatives provide a vast reservoir of genetic variability for most, if not all, agronomically important traits. Genetic variation has previously been transferred to wheat from one of its wild relatives, Ambylopyrum muticum (previously known as Aegilops mutica). However, before the genetic variation available in this species can be assessed and exploited in breeding and for research, the transmission of the chromosome segments introgressed into wheat must first be stabilized. In this paper we describe the generation of 66 stably inherited homozygous wheat/Am. muticum introgression lines using a doubled haploid procedure. The characterisation and stability of each of these lines was determined via genomic in situ hybridization and SNP analysis. While most of the doubled haploid lines were found to carry only single introgressions, six lines carried two. Three lines carried only complete Am. muticum chromosomes, 43 carried only small or very small introgressions and the remainder carried either only large introgressions or a large plus a small introgression. The strategy that we are employing for the distribution and exploitation of the genetic variation from Am. muticum and a range of other species is discussed.

Keywords: wheat, introgression, Amblyopyrum muticum, doubled haploid, SNP markers, genomic in situ hybridization

Introduction

Wheat is one of the world’s leading sources of food providing circa 20% of the world’s daily intake (Reynolds et al., 2012). Following a history of continued yield improvements by breeders, wheat yields are now plateauing at a time when the world’s population is rapidly increasing (Charmet, 2011). The reason for this plateauing is a lack of genetic variation within modern day wheat varieties compounded by environmental change, i.e., hexaploid wheat only evolved once or twice circa 10,000 years ago and thus it has been through a significant genetic bottle-neck. In contrast to wheat its wild relatives provide a vast reservoir of genetic variation for potentially most, if not all, traits of agronomic importance. In the past there have been several examples of the exploitation of genetic variation from wild relatives for wheat improvement. For example, the transfer of a segment of Aegilops umbellulata to wheat conferring resistance to leaf rust (Sears, 1955), the transfer of a segment of Aegilops ventricosa carrying resistance to eyespot (Doussinault et al., 1983) and its subsequent release as the variety Rendevouz.

Even though there have been a number of successes in the past, the genetic variation available within the wild relatives remains largely untapped with regard to its exploitation in breeding programs. The main reason for this has been the lack of high throughput technological screens to identify when genetic variation has been introgressed into wheat. A direct result is that where in the 1970s and 1980s there were many hundreds of scientists working in the field there are now very few. However, the advances in technology, e.g., gene and genome sequencing, comparative mapping, molecular marker development etc., over the last 10–15 years has now resulted in the development of systems that can be utilized for the high throughput detection and high-resolution characterisation of wheat/wild relative introgressions. King et al. (2017, 2018) and Iefimenko et al. (2015) used an Axiom array in combination with a specific crossing strategy to generate and identify introgressions from Ambylopyrum muticum, Aegilops speltoides and Thinopyrum bessarabicum. Many hundreds of new introgressions were generated and detected in these works. The frequency of introgression between wheat and Am. muticum and Ae. speltoides was high enough to generate linkage maps of these species, with over 500 new introgressions developed from Am. muticum and Ae. speltoides (King et al., 2017, 2018).

In the past much of the work undertaken had been aimed at transferring genetic variation from a wild relative to wheat for a single trait. This strategy normally required the production of an interspecific hybrid followed by the generation of wheat/wild relative addition and substitution lines (King et al., 2016). A chromosome manipulation program was then undertaken to introgress a small chromosome segment, from the chromosome of the wild relative (that carried the gene(s) controlling the target trait) into wheat. The work undertaken by King et al. (2017, 2018) and Iefimenko et al. (2015) used a different strategy. Although Am. muticum Ae. speltoides and Th. bessarabicum all carry genetic variation for a range of traits such as disease resistance, salt tolerance, etc., the main aim of these works was to introgress the entire genome of these species into wheat in small chromosome segments, i.e., transfer all of the genetic variation in these species into wheat. In the future each of the introgression lines carrying a chromosome segment from these three wild relatives will be screened phenotypically for a range of traits. This strategy will allow the phenotypic analysis of the entire genomes of each of the wild relatives for a wide range of traits (the limiting factor being the number of traits screened for) rather than a single trait.

In order for each of the introgression lines to be analyzed phenotypically they need to be multiplied and stably inherited. All of the introgressions initially produced byKing et al. (2017, 2018) and Iefimenko et al. (2015) are in the heterozygous state with the result that the progeny produced from plants carrying them will segregate for lines with and without the introgression. In contrast, lines homozygous for introgressions are expected to be stably inherited and thus can be multiplied and distributed for large scale trait analysis.

In this work, however, we focused on the development of homozygous Am. muticum introgression lines a species that has been shown with limited previous trait analysis to contain genetic variation for environmental stresses (Iefimenko et al., 2015) and powdery mildew (Eser, 1998) and their characterisation via SNP analysis and genomic in situ hybridization (GISH). The strategy for exploitation of introgressions is discussed, i.e., all stable homozygous introgressions that are generated will be subjected to a wide range of trait analyses via our collaborators both in the United Kingdom and globally, in order to determine the agronomic and scientifically important genetic variation carried by the Am. muticum introgressions.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

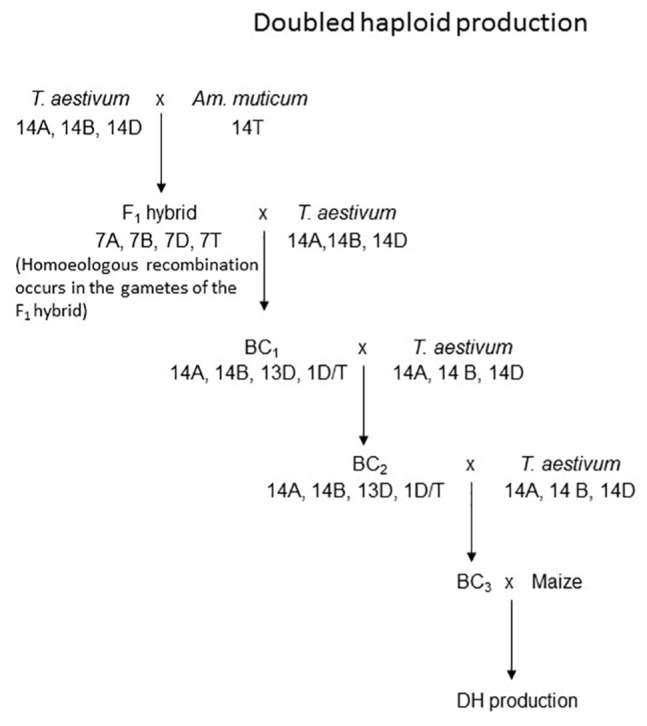

Wheat/Am. muticum introgressions were generated as described by King et al. (2017). In summary T. aestivum, vars. Chinese Spring and Pavon 76, were pollinated with Am. muticum (which carries suppressors of Ph1/promoters of homoeologous recombination). Accessions 2130004 and 2130012 of Am. muticum were obtained from the Germplasm Resource Unit at the JIC, United Kingdom. The F1 interspecific hybrids produced were then backcrossed to T. aestivum vars. Paragon or Pavon 76 to recover introgressions in a wheat background. The BC1 population and its subsequent progeny were also backcrossed to Paragon to produce a BC3 populations which were themselves crossed to maize to initiate doubled haploid (DH) production (Figure 1). When the work described in this paper was initially undertaken the Axiom® Wheat-Relative Genotyping Array described by King et al., 2017 was not available. Thus, selection of BC3 plants for DH production was based upon the identification of plants carrying introgressions in the BC2 individuals via GISH analysis. However, leaf material was taken from each of the BC3 plants used for DH production for SNP analysis when the genotyping array became available.

FIGURE 1.

Derivation of the material used to develop DH homozygous introgression lines. This example shows an ideogram of an Am. muticum/T. aestivum D genome recombinant and the subsequent development of a DH line from it.

Doubled Haploid Production

The DH production procedure used was as described by Laurie and Reymondie (1991). In summary 1 day after pollination with maize (cultivars Northern Extra Sweet, Prelude and Sundance), internodes below pollinated spikes were filled with 10 mg l-1 of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D solution) with a syringe and the holes sealed with petroleum jelly. The 2,4-D solution was also injected into each floret. After 14–21 days embryos were excised and cultured. Colchicine treatment was carried out as described in Nemeth et al. (2015).

Detection of Wheat/Am. muticum Introgressions

Marker Analysis

A 35K Axiom® Wheat-Relative Genotyping Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, United States) was used to genotype a set of BC1, BC2 and BC3 wheat/Am. muticum introgression lines by King et al. (2017). The genetic map generated for Am. muticum by King et al. (2017) was used in conjunction with the 35K Axiom® Wheat-Relative Genotyping Array to detect and characterize Am. muticum segments in the DH lines and in the BC3 lines they originated from as described in King et al. (2017). [All the SNPs incorporated in the array formed part of the Axiom® 820K SNP array (Winfield et al., 2016) with the dataset for the Axiom® 820K SNP Array available at www.cerealsdb.uk.net (Wilkinson et al., 2012, 2016)]. The SNPs used were polymorphic between Am. muticum and the three wheat cultivars used in the generation of the DH lines (Chinese Spring, Paragon and Pavon 76). Also, most SNPs were not genome-specific in wheat, i.e., they had copies on more than one genome of wheat and thus, were unable to distinguish between a heterozygous and a homozygous segment since presence of either type of segment produced a heterozygous call.

Cytogenetic Analysis

The protocol for genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) was as described in Zhang et al. (2013); Kato et al. (2004), and King et al. (2017). Genomic DNAs was isolated from Am. muticum and the three putative diploid progenitors of bread wheat, i.e., T. urartu (A genome), Ae. speltoides (B genome) and Ae. tauschii (D genome). Genomic DNAs of Am. muticum, T. urartu and Ae tauschii were labeled by nick translation with ChromaTide Alexa Fluor 546-14-dUTP, ChromaTide Alexa Fluor 488-5-dUTP [Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen), Waltham, MA, United States] and Alexa Fluor 594-5-dUTP [Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen), Waltham, MA, United States], respectively. Genomic DNA of Ae. speltoides was fragmented to 300–500 bp at 100°C.

Preparation of chromosome spreads was as described in Kato et al. (2004) and King et al. (2017). Slides were probed using labeled genomic DNAs of Am. muticum (100 ng), T. urartu (100 ng), Ae. tauschii (200 ng) and fragmented genomic DNA of Ae. speltoides (5000 ng) as blocker in a ratio of 1:1:2:50 per slide to detect the Am. muticum introgressions and the AABBDD genomes of wheat. Slides were counterstained with Vectashield mounting medium with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole,dihydrochloride (DAPI) and analyzed using a Zeiss Axio ImagerZ2 upright epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Ltd, Oberkochen, Germany) with filters for DAPI (Ex/Em 358/461 nm, blue), Alexa Fluor 488 (Ex/Em 490/520 nm, green), Alexa Fluor 594 (Ex/Em 590/615 nm, red) and Alexa Fluor 546 (Ex/Em 555/570 nm, yellow). Photographs were taken using a MetaSystems Coolcube 1 m CCD camera. Further slide analysis was carried out using Meta Systems ISIS and Metafer software (Metasystems GmbH, Altlussheim, Germany).

Results

Sixty-nine BC3 plants derived from BC2 lines (characterized by GISH and identified as carrying Am. muticum chromosomes and introgressions) were pollinated with maize in order to generate DH lines. Subsequent SNP analysis of the 69 BC3 plants using the newly developed Axiom® Wheat-Relative Genotyping Array indicated that 57 of the 69 BC3 individuals selected carried Am. muticum chromosomes and/or wheat/Am. muticum introgressions. Of the 12 BC3 plants that did not carry Am. muticum chromosomes and wheat/Am. muticum introgressions 11 (92%) produced DHs (Supplementary Table S1).

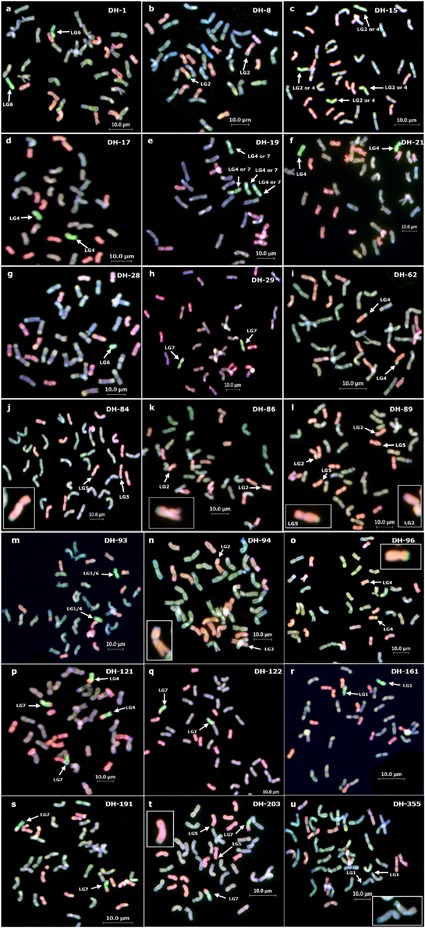

Of the 57 BC3 plants carrying Am. muticum chromosomes and/or wheat/Am. muticum introgressions 32 (56%) produced DHs. In total 220 DH plants were produced of which 161 (73%) grew and produced seed. The remaining 59 (27%) DHs either died or were sterile. SNP analysis indicated that of the 161 DH plants that set seed, 93 (58%) did not carry any Am. muticum chromosomes and/or wheat/Am. muticum introgressions (Supplementary Table S1). SNP analysis revealed that the remaining 68 DH plants that set seed all carried one or two wheat/Am. muticum introgressions or chromosomes (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Table 1 gives the genome information for one DH plant for each different segment - each of these selected plants is also shown with GISH in Figure 2. Full genome information for all BC3 plants used and all DH plants produced is given in Supplementary Table S1. DH-4 was subsequently lost due to very low seed set and germination. Fifty seven of the lines were analyzed using multi-color GISH (mcGISH; Figure 2 shows the GISH for one DH plant for each different segment) and the linkage group of the Am. muticum and/or wheat/Am. muticum introgression that each DH derived line was determined via SNP analysis (Table 1). SNP analysis revealed that one of the lines, DH-93, carried linkage group 1L and linkage group 6S markers. However, cytogenetic analysis indicated the presence of a single pair of chromosomes. Since previous work has shown that Am. muticum linkage group 6 and group 1 chromosomes are not translocated relative to wheat (King et al., 2017) this observation indicates the presence of a translocated Am. muticum 6S.1L chromosome potentially derived from mis-division of complete chromosomes followed by centric fusion.

Table 1.

Genome information for BC3 and DH plants showing the number, linkage groups and size of Am. muticum segments present, the wheat genome involved in the recombination (where known) and the number of A, B, and D genome chromosomes.

| BC3 code | No. of segments in BC3 | No. of DH plants produced with segment(s) | DH plant with GISH validation | No. of segments in DH plants | Linkage group of DH segments | Segment size | Wheat genome recombined with | No. of A chromosomes | No. of B chromosomes | No. of D chromosomes | Total No. of chromosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 165D | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Whole | 14/16 | 14 | 12 | 42/44 | |

| 174D | 1 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | Very small | D | 14 | 14 | 14 | 42 |

| 177A | 2 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 2, 4 | Large, Large | B, B | 12 | 14 | 14 | 42 |

| 17 | 1 | 4 | Large | B | 14 | 12 | 14 | 42 | |||

| 177B | 2 | 3 | 19 | 2 | 4, 7 | Large, Large | B, B | 14 | 12 | 14 | 42 |

| 21 | 1 | 4 | Large | B | 14 | 12 | 14 | 42 | |||

| 182B | 2 | 2 | 28 | 1 | 6 | Telo | 14/15 | 13/14 | 14 | 41/42/43 + /-T | |

| 29 | 1 | 7 | Whole | 14 | 14 | 11 | 41 | ||||

| 185A | 1 | 11 | 62 | 1 | 4 | Small | D | 14 | 14 | 13/14 | 41/42 |

| 186A | 4 | 7 | 84 | 1 | 5 | Very small | D | 14 | 14 | 14 | 42 |

| 86 | 1 | 2 | Very small | D | 12 | 14 | 16 | 42 | |||

| 89 | 2 | 2, 5 | Very small, Very small | D, D | 12 | 14 | 16 | 42 | |||

| 187A | 4 | 2 | 93 | 1 | 1/6cf | Whole | Centric fusion | 12 | 14 | 12 | 40 |

| 94 | 1 | 2 | Small | D | 12 | 14/15 | 16 | 42/43 | |||

| 187B | 3 | 2 | 96 | 1 | 4 | Small | D | 14 | 14 | 14 | 42 |

| 189B | 2 | 3 | 121 | 2 | 4, 7 | Large, Large | D, D | 14 | 14 | 10 | 42 |

| 122 | 1 | 7 | Large | D | 14 | 14 | 12 | 42 | |||

| 190A | 1 | 15 | 355 | 1 | 1 | Very small | A | 16 | 12 | 14 | 42 |

| 194A | 2 | 1 | 161 | 1 | 1 | Large | B | 12 | 14 | 12 | 40 |

| 197B | 1 | 8 | 191 | 1 | 7 | Large | D | 14 | 14 | 12 | 42 |

| 197E | 2 | 1 | 203 | 1 | 7 | Very small, Large | D, D | 14 | 14 | 12 | 42 |

Of the 68 DH lines with segment(s) only GISH validated DH lines (represented in Figure 2) have detailed information shown above. For complete genome information on all DH lines produced, including those with no segments, see supplemental data (Supplementary Table S1).

FIGURE 2.

GISH analysis of DH lines showing the different segments present. (a) DH-1 (b) DH-8 (c) DH-15 (d) DH-17 (e) DH-19 (f) DH-21 (g) DH-28 (h) DH-29 (i) DH-62 (j) DH-84 (k) DH-86 (l) DH-89 (m) DH-93 (n) DH-94 (o) DH-96 (p) DH-121 (q) DH-122 (r) DH-161 (s) DH-191 (t) DH-203 (u) DH-355. All GISH was carried out using four colors as indicated in Materials and Methods, but all photos shown were taken using three colors with a green filter for Alexa Fluor 546 for best visualization of the Am. muticum segments (bright green segment indicated with white arrows). The A and B genome chromosomes are colored the same (blue/light green) under this color capture. The D genome is shown in red. Small segments are also shown as enlargements.

McGISH analysis of the progeny derived from the 67 fertile DH individuals indicated that the wheat/Am. muticum introgressions and complete chromosomes were stably transmitted to the next generation with one exception. DH-28 was found to be heterozygous for a telosome derived from Am. muticum linkage group 6 (Figure 2g). As a result, the progeny derived from this DH segregated for the presence or absence of this chromosome.

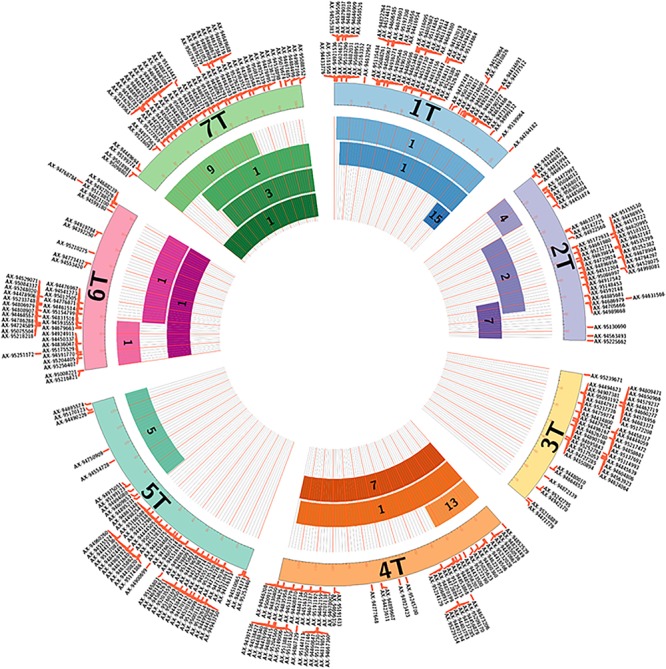

The DH plants produced carried segments from linkage groups 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (Figure 3) although the introgressed segments did not cover the whole of these linkage groups. Only one DH plant (DH-4) was found to contain a segment from linkage group 3. However, this plant was subsequently lost as the pollen fertility was very low and thus the line produced very few seed which were shriveled and failed to germinate.

FIGURE 3.

Size of the Am. muticum segments within the DH lines and their coverage of the Am. muticum genome visualized using Circos v. 0.67 (Krzywinski et al., 2009). The numbers within each segment shows the number of lines containing that segment. The sizes of the chromosomes and the markers on them are obtained from the genetic map of Am. muticum (King et al., 2017).

McGISH also revealed that while the introgressions/ chromosomes were largely stably inherited, the number of chromosomes of each wheat genome varied in some of the DH lines (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1 and Figure 2). For example, DH-1 carried a pair of Am. muticum group 6 chromosomes but the number of A genome chromosomes varied, i.e., two plants carried 14 A genome chromosomes, 14 B chromosomes and 12 D chromosomes, while a third plant carried 16 A genome chromosomes, 14 B genome chromosomes and 12 D genome chromosomes. In addition to wheat/Am. muticum introgressions, several lines also carried intergenomic wheat recombinants, e.g., A/B, A/D recombinants.

Discussion

In the past, attempts to introduce genetic variation from a wild relative have generally focused on introgressing a single chromosome segment carrying genetic variation for a single trait [frequently using substitution lines/addition lines as a starting point (King et al., 2016)]. In contrast the objective of the work described here is not focused on just single traits, i.e., we are attempting to identify useful genetic variation for a wide range of traits from Am. muticum for future exploitation. In order to do this, we aim to generate very large numbers of introgressions in wheat from Am. muticum (ideally, we would like to introgress the entire genome of Am. muticum into wheat). In order to identify as much genetic variation as possible, a wide range of trait analyses will be performed on each introgression line generated (by ourselves and collaborators in both the public and private sectors globally). In addition, all lines derived from the (BBSRC funded) Wheat Research Centre at the University of Nottingham will be made available upon request (subject to handling charges, e.g., phytosanitary certificates).

A key factor in this strategy is the bulking and distribution of seed for trait analysis. However, before seed can be bulked each individual introgression must first be in a homozygous state to ensure that it is stably inherited to the next generation (all the introgressions we generate are initially in a heterozygous state and thus, any progeny derived from them will segregate for their presence and absence). The generation of DH lines in the work described in this paper represents one of the methods we are employing to generate homozygous introgression lines. In this work, 56% (32) of BC3 plants carrying an Am. muticum chromosome or introgression produced DHs as compared to 92% (11) of BC3 plants which did not carry Am. muticum chromosomes or introgressions. From the 32 BC3 plants a total of 220 DH plants were produced, but only 68 of those that produced seed carried Am. muticum introgressions or chromosomes (with one of these lines being subsequently lost). These results indicate that the DH technique has resulted in the successful generation of homozygous introgressions albeit at a relatively low frequency. However, further work is required to optimize the protocols used to increase the frequency of DH generation from lines carrying introgressions and chromosome segments from the wild relatives of wheat, e.g., 2,4-D concentration, timing of embryo excision, colchicine concentration, etc.

One of the key objectives of the work outlined above is to introgress the entire genome of Am. muticum into wheat. The lines described here do not cover the entire genome as shown in Figure 3. In particular, the stable lines produced do not contain any segments from linkage group 3 of Am. muticum. However, it is difficult to establish at this stage if the regions not represented point to regions of the genome that are recalcitrant to transmission or are simply not represented due to the relatively small sample size. We also did not observe any examples of where an introgression was detected by SNP analysis that was not detected by GISH analysis (cryptic introgressions). However, again due to the relatively small sample size, it was not possible to determine if cryptic introgressions do or do not occur.

Initially, lines homozygous for large introgressions are being generated, distributed, e.g., Australia, United States, commercial breeding companies, and are being used for preliminary trait analyses. This initial analysis will enable the determination of which regions of the genome of Am. muticum carry genetic variation for target traits. The second stage of analysis will focus on the analysis of small introgressions derived from the large regions that have been found to carry target genetic variation (homozygous lines will need to be generated for each of the small introgression lines prior to the distribution for trait analysis). In this way we will identify the smallest introgression that carries the gene(s) controlling the target trait (the smaller the introgression the less likely it will be that it will carry deleterious genes in addition to the target gene). If small introgressions are not available, then overlapping introgressions will be intercrossed to produce smaller ones as described by Sears (1955) or further introgressions will be generated.

A further requirement of the strategy being undertaken is that once homozygous, each introgression must be stably inherited. Out of the viable 67 DH lines generated only one, DH-28 (1.5%), was not stably inherited. The remaining 66 DH (98.5%) were found to be stably inherited.

A number of abnormalities were observed within the wheat genome, e.g., the number of chromosomes of the three wheat genomes was occasionally found to vary from the euploid condition (i.e., 14 A, 14 B and 14D chromosomes). In addition, intergenomic recombinants were observed between the three genomes of wheat. The reason for these abnormalities may result from the strategy that was employed to generate introgressions, i.e., euploid wheat was pollinated with Am. muticum to produce an interspecific F1 hybrid which was then backcrossed to euploid wheat to produce a BC1 population. The F1 hybrids generated were haploid for each of the three wheat genomes and the Am. muticum genome and thus the only recombination that could occur was between homoeologous chromosomes (King et al., 2017, 2018). However, while this strategy resulted in the generation of a high frequency of wheat/Am. muticum recombination and hence introgressions it also appears to have led to the generation of homoeologous recombination between the three genomes of wheat.

The variable aneuploid number of A, B and D genome chromosomes was probably also derived from the interspecific F1s, i.e., the haploid genome complement of the F1 would have resulted in the production of unbalanced gametes and thus variable numbers of A, B and D genome chromosomes in the BC1 generation. In order to restore the diploid chromosome complement of the wheat genome and to remove any wheat/wheat intergenomic recombinants, further backcrossing will be required.

Of the 66 stable DHs generated, 23 that carry large segments, and upon request from our collaborators a further five carrying small introgressions, have now been released. The remaining DHs will be made available in the near future. In this program, we have demonstrated that DH procedures can be used to generate homozygous introgression lines. However, in addition to using DH procedures we are also generating homozygous introgression lines via self-fertilization of heterozygous lines and progeny testing. To assist us in identifying homozygous introgression lines (produced either by DH technology or by self-fertilization) we are developing circa 1000 KASP markers to facilitate selection.

In this paper, we have only described work on one wild relative, i.e., Am. muticum. However, we are working on a number of other species and we aim to use DH techniques and self-fertilization to initially produce large homozygous introgressions that span the genomes of these relatives (and smaller homozygous introgressions as required). Thus, over the coming years, many hundreds of homozygous introgression lines will be made available for trait analysis. In this way we intend to facilitate the large-scale exploitation of genetic variation from the wild relatives of wheat for wheat improvement.

In the past, there has been some reticence in using genetic variation from the wild relatives of wheat, mainly stemming from the fact that target genes may also be associated with deleterious genes. However, the development of new technologies provides the means by which this problem can now be overcome. We believe the biggest threat to the exploitation of genetic variation from wheat’s wild relatives, lies in the fact that whereas there were hundreds of active scientists in the field in the 1970s and 1980s, very few with the requisite expertise now remain.

Author Contributions

JK, SG, C-yY, SH-E, DS, SA, and IK carried out the crossing program. CN and AS carried out the doubled haploid production. SG analyzed the genotyping data. C-yY carried out the genomic in situ hybridization. IK wrote the manuscript with assistance from JK. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Keith Edwards, Dr. Alexandra Allen, and Dr. Amanda Burridge for their technical assistance in the genotyping.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [grant number BB/P016855/1] as part of the Designing Future Wheat Programme (DFW). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.00034/full#supplementary-material

References

- Charmet G. (2011). Wheat domestication: lessons for the future. C. R. Biol. 334 212–220. 10.1016/j.crvi.2010.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doussinault G., Delibes A., Sanchezmonge R., Garcia-Olmedo F. (1983). Transfer of a dominant gene for resistance to eyespot disease from a wild grass to hexaploid wheat. Nature 303 698–700. 10.1038/303698a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eser V. (1998). Characterisation of powdery mildew resistant lines derived from crosses between Triticum aestivum and Aegilops speltoides and Ae. mutica. Euphytica 100 269–272. 10.1023/A:1018372726968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal S., Yang C., Hubbart Edwards S., Scholefield D., Ashling S., Burridge A. J., et al. (2018). Characterisation of Thinopyrum bessarabicum chromosomes through genome-wide introgressions into wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131 389–406. 10.1007/s0012-017-3009-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iefimenko T. S., Fedak Y. G., Antonyuk M. Z., Ternovska T. K. (2015). Microsatellite analysis of chromosomes from the fifth homoeologous group in the introgressive Triticum aestivum/Amblyopyrum muticum wheat lines. Cytol. genet. 49 183–191. 10.3103/S0095452715030056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A., Lamb J. C., Birchler J. A. (2004). Chromosome painting using repetitive DNA sequences as probes for somatic chromosome identification in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 13554–13559. 10.1073/pnas.0403659101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J., Grewal S., Yang C., Hubbart-Edwards S., Scholefield D., Ashling S., et al. (2017). A step change in the exploitation of interspecific variation into wheat from Amblyopyrum muticum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15 217–226. 10.1111/pbi.12606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J., Grewal S., Yang C., Hubbart-Edwards S., Scholefield D., Ashling S., et al. (2018). Introgression of Aegilops speltoides segments in Triticum aestivum and the effect of the gametocidal genes. Ann. Bot. 121 229–240. 10.1093/aob/mcx149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J., Gustafson P., Allen A., King I. (2016). “Exploitation of interspecific diversity in wheat,” in The World Wheat Book: A History of Wheat Breeding Vol. Vol. 3 eds Bonjean A. P., Angus W. J., van Ginkel M. (Paris: Lavoisier; ), 1125–1139. 10.1111/pbi.12606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19 1639–1645. 10.1101/gr.092759.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie D. A., Reymondie S. (1991). High frequencies of fertilization and haploid seedling production in crosses between commercial hexaploidy wheat varieties and maize. Plant Breed. 106 182–189. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1991.tb00499.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth C., Yang C., Kasprzak P., Hubbart S., Scholefield D., Mehra S., et al. (2015). Generation of amphidiploids from hybrids of wheat and related species from the genera Aegilops, Secale, Thinopyrum and Triticum as a source of genetic variation for wheat improvement. Genome 58 71–79. 10.1139/gen-2015-0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M., Foulkes J., Furbank R., Griffiths S., King J., Murchie E., et al. (2012). Achieving yield gains in wheat. Plant, Cell Environ. 35 1799–1823. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02588.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears E. R. (1955). An induced gene transfer from Aegilops to Triticum. Genetics 40:595. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P. A., Winfield M. O., Barker G. L. A., Allen A. M., Burridge A., Coghill J. A., et al. (2012). CerealsDB 2.0: an integrated resource for plant breeders and scientists. BMC Bioinform. 13:219. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P. A., Winfield M. O., Barker G. L. A., Tyrell S., Bian X., Allen A. M., et al. (2016). CerealsDB 3.0: expansion of resources and data integration. BMC Bioinform. 17:256. 10.1186/s12859-016-1139-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield P. A., Winfield M. O., Barker G. L. A., Tyrrell S., Bian X., Allen A. M., et al. (2016). High-density SNP genotyping array for hexaploidy wheat and its secondary and tertiary gene pool. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14 1195–1206. 10.1186/s12859-016-1139-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Bian Y., Gou X., Zhu B., Xu C., Qi B., et al. (2013). Persistent whole chromosome aneuploidy is usually associated with nascent allohexaploid wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 3447–3452. 10.1073/pnas.1300153110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.