Abstract

Background

This study evaluated the hemoglobin dose response, other efficacy measures and safety of daprodustat, an orally administered, hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor in development for anemia of chronic kidney disease.

Methods

Participants (n = 216) with baseline hemoglobin levels of 9–11.5 g/dL on hemodialysis (HD) previously receiving stable doses of recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO) were randomized in a 24-week dose-range, efficacy and safety study. Participants discontinued rhEPO and then were randomized to receive daily daprodustat (4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 mg) or control (placebo for 4 weeks then open-label rhEPO as required). After 4 weeks, doses were titrated to achieve a hemoglobin target of 10–11.5 g/dL. The primary outcome was characterization of the dose–response relationship between daprodustat and hemoglobin at 4 weeks; additionally, the efficacy and safety of daprodustat were assessed over 24 weeks.

Results

Over the first 4 weeks, the mean hemoglobin change from baseline increased dose-dependently from −0.29 (daprodustat 4 mg) to 0.69 g/dL (daprodustat 10 and 12 mg). The mean change from baseline hemoglobin (10.4 g/dL) at 24 weeks was 0.03 and −0.11 g/dL for the combined daprodustat and control groups, respectively. The median maximum observed plasma EPO levels in the control group were ∼14-fold higher than in the combined daprodustat group. Daprodustat demonstrated an adverse event profile consistent with the HD population.

Conclusions

Daprodustat produced dose-dependent changes in hemoglobin over the first 4 weeks after switching from a stable dose of rhEPO as well as maintained hemoglobin target levels over 24 weeks.

Keywords: anemia, chronic kidney disease, daprodustat, hemodialysis, recombinant human erythropoietin

INTRODUCTION

Anemia is a common complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who receive maintenance hemodialysis (HD) [1, 2]. The standard of care for treating this anemia uses recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO) and its analogs, supplemented with intravenous (IV) iron administration [3]. Well-controlled clinical outcomes trials have demonstrated that rhEPO and its analogs increase the risk of cardiovascular events, stroke and death when targeting higher hemoglobin levels (>13 g/dL) [4–7]. These findings led the US Food and Drug Administration to modify safety language in labeling for rhEPO and its analogs in 2007 and 2011 to limit their initiation in HD patients until the hemoglobin level is <10 g/dL and to reduce or interrupt treatment if the hemoglobin level approaches or exceeds 11 g/dL [8, 9].

Given the safety concerns with rhEPO and its analogs, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (PHIs) including daprodustat (previously GSK1278863) are being developed to treat anemia of CKD [10–14]. These agents stimulate erythropoiesis by inhibiting the HIF-prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) enzymes PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3. This leads to stabilization of HIF-α transcription factors and induction of HIF-responsive genes involved in adaptation to hypoxia—including erythropoietin (EPO), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and genes that regulate iron uptake, mobilization and transport—resulting in decreased hepcidin production [15, 16]. Potential advantages of HIF-PHI agents over rhEPO and its analogs, which are being tested in long-term studies, include increasing hemoglobin without exposing the patient to the supraphysiologic EPO levels associated with rhEPO and its analogs, improving iron availability for erythropoiesis and correction of anemia in patients who do not respond to rhEPO and its analogs and treating anemia without producing hypertension. It is postulated, for these reasons, that daprodustat may be associated with fewer cardiovascular events than rhEPO and its analogs.

A previous 4-week study with daprodustat demonstrated its ability to maintain hemoglobin levels in HD patients who switched from rhEPO [13]. The effects of daprodustat on hemoglobin were achieved with small increases in circulating EPO levels that averaged 17-fold lower than in the rhEPO control group [17]. We report the results of a trial designed to further evaluate the dose–response relationship between daprodustat and hemoglobin levels over the first 4 weeks of treatment (primary endpoint) and to evaluate the safety and efficacy of daprodustat over 24 weeks in achieving and maintaining hemoglobin levels within a prespecified target range (10–11.5 g/dL) in HD participants switched to daprodustat from a stable dose of rhEPO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Eligible participants were on adequate HD three to five times weekly, on stable rhEPO doses for 8 weeks before randomization and had stable hemoglobin levels between 9 and 11.5 g/dL based on the average of three values obtained during the screening phase. Maintenance oral or IV iron supplementation was allowed, but participants were excluded if ferritin was <100 ng/mL and/or transferrin saturation (TSAT) was <12% or >57%. The complete inclusion, exclusion and study medication stopping criteria and prohibited drugs can be found in the Supplementary data, Item S1, and the iron protocol is shown in Supplementary data, Table S1 in Item S2.

Study design

This global study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01977482; EudraCT number 2013-002682-19) was conducted from 15 November 2013 to 18 March 2015 at 107 sites in 16 countries (67 sites in 15 countries randomized participants), performed in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by relevant institutional review boards or ethics committees. The investigators or study site staff were responsible for detecting, documenting and reporting adverse events (AEs). An internal GlaxoSmithKline Safety Review Team reviewed blinded safety data in stream and an independent data monitoring committee periodically reviewed the same safety data but unblinded.

The study consisted of a 4-week screening phase, 24-week treatment phase and a follow-up visit ∼4 weeks after completing treatment. Participants who discontinued study medication or withdrew early from the study attended an early withdrawal (EW) visit, a follow-up visit after 4 weeks, phone assessments aligned with the remaining key study visits as required and an EW final visit at Week 24. Study investigators or staff were responsible for monitoring and recording AEs. AEs were collected from the start of study treatment and until the follow-up contact. (Additional information regarding the study design is included in the Supplementary data, Item S3 and Figure S1.) Eligible participants were stratified by region (Japan versus non-Japan) and prior rhEPO dose and then randomized 2:2:2:2:1:2 to receive blinded daprodustat tablets once daily at starting doses of 4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 mg or placebo tablets (control group).

At Week 4, the daprodustat and control groups were to have doses adjusted in order to achieve and maintain hemoglobin within the prespecified target range (10–11.5 g/dL). Participants randomized to daprodustat had automatic dose adjustments through an interactive voice/web response system based on a prespecified dose-adjustment algorithm, with the dose of daprodustat continually being blinded. Control participants received open-label rhEPO (epoetins or their biosimilars, or darbepoetin), with the rhEPO type, dose and route of administration being determined by the investigator. Study medications were permanently discontinued if hemoglobin levels were <7.5 g/dL, and participants were managed per standard of care (e.g. rhEPO and its analogs and/or iron). (A complete description of the primary and secondary endpoints and associated study assessments are listed in Table 1.) Details of the study assessments performed, including laboratory assessments, AE reporting, echocardiology and ophthalmology exams, are listed in Supplementary data, Item S4.

Table 1.

Study objectives and endpoints

| Objectives | Endpoints | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Characterize the dose–response relationship between daprodustat and hemoglobin at Week 4 |

|

| Secondary | Characterize the ability of daprodustat to achieve hemoglobin within the target range (10.0–11.5 g/dL) |

|

| Characterize the effect of daprodustat on measures of iron metabolism and utilization, on indices of hematopoiesis and EPO and on VEGF |

|

|

| Safety | Assess the safety and tolerability of daprodustat following QD administration for 24 weeks |

|

AE, adverse event; CHr, reticulocyte hemoglobin content; CV, cardiovascular; EPO, erythropoietin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; QD, once daily; RBC, red blood cell; SAE, severe adverse event; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; TIBC, total iron-binding capacity; TSAT, transferrin saturation; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. All analyses were estimation based; no formal hypothesis testing was planned. Results are expressed using descriptive statistics.

For the primary analysis, a Bayesian approach was used to characterize the relationship between daprodustat dose and hemoglobin using an Emax model (details are described in the Supplementary data, Item S5). For the secondary analysis, time (days) spent with hemoglobin within the target range while on treatment between Weeks 20 and 24 was calculated using the method of Rosendaal et al. [18] and percentage of time within, above, and below hemoglobin target range between Weeks 20 and 24 was reported. The number of participants within, above and below the hemoglobin target range was determined at Week 24. Safety data were summarized by treatment group. This study was designed as a dose-ranging study and, as such, was not designed to make any formal comparisons between the daprodustat and control arms.

The sample size for daprodustat was sufficient to estimate the dose–response relationship and to provide data on at least 100 participants exposed to daprodustat for 24 weeks (see Supplementary data, Item S5 for complete justification).

RESULTS

Participant disposition and baseline characteristics

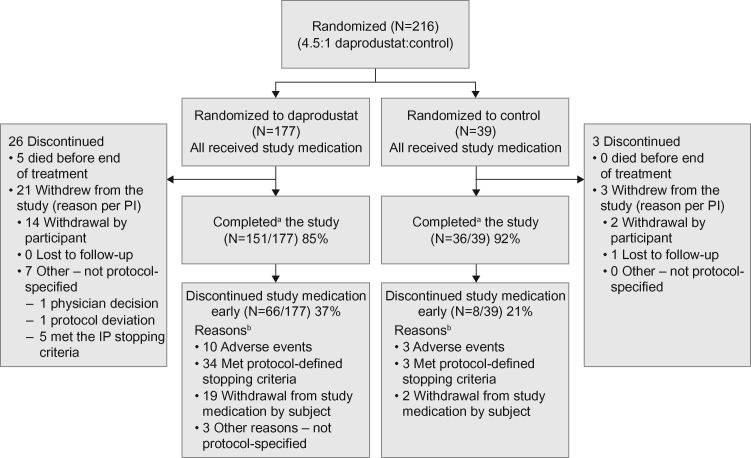

The study included 177 participants randomized to one of the daprodustat dose groups and 39 participants randomized to the control group. Of those randomized, all were included in the safety population and 171 (97%) in the ITT population. The overall study completion rate was 87%, with 85% of participants in the daprodustat and 92% in the control groups completing the study, i.e. the participant completed all study visits or the abbreviated schedule if study medication was discontinued (Figure 1). The predominant reason in both groups for participants not completing the study was withdrawal by the participant (withdrew consent): 8% in the combined daprodustat group and 5% in the control group. For those randomized to daprodustat, the highest rates of noncompleters were in groups with a starting dose of daprodustat of 4 or 12 mg.

FIGURE 1:

Study flow diagram.aCompleted all study visits or abbreviated schedule if study medication was discontinued. bTwenty-two participants discontinued study medication because of AEs; however, 12 of these participants had AEs that were actually protocol-defined stopping criteria and are presented here in the stopping criteria category rather than the AE category. Protocol-defined stopping criteria are detailed in the Supplementary data, Item S1. IP, investigational product; PI, principal investigator.

Baseline and demographic characteristics are shown for the daprodustat and control groups (Table 2). In the ITT population, mean age (57.9 and 61.6 years), percentage of males (65% and 60%), mean weight (80.3 and 84.8 kg) and mean body mass index (28.2 and 30.1 kg/m2) were well balanced in the combined daprodustat and control groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Baseline and demographic characteristics (ITT population and safety population where indicated)

| Combined daprodustat | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 171) | (n = 39) | |

| Agea, years | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| mean (SD) | 59.6 (13.3) | 59.7 (18.7) |

| Sexa | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| male, n (%) | 108 (63) | 26 (67) |

| Weighta (kg) | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| mean (SD) | 77.8 (23.0) | 76.3 (19.8) |

| BMIa (kg/m2) | ||

| n | 170 | 39 |

| mean (SD) | 27.7 (7.5) | 27.2 (5.8) |

| Racea, n (%) | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| White | 124 (73) | 23 (59) |

| African American | 18 (11) | 7 (18) |

| Asian | 27 (16) | 7 (18) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 2 (5) |

| Geographical regiona, n (%) | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| Japan | 19 (11) | 5 (13) |

| North America | 44 (26) | 13 (33) |

| Russia | 37 (22) | 9 (23) |

| Rest of the world | 71 (42) | 12 (31) |

| Mode of dialysisb, n (%) | ||

| n | 177 | 39 |

| Hemodiafiltration | 51 (29) | 5 (13) |

| HD | 120 (68) | 33 (85) |

| Hemofiltration | 6 (3) | 2 (5) |

| Prior rhEPO dose stratificationa,c, n (%) | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| Low rhEPO dose | 143 (84) | 33 (85) |

| High rhEPO dose | 28 (16) | 6 (15) |

| Baseline hemoglobin levela (g/dL) | ||

| n | 171 | 39 |

| mean (SD) | 10.4 (0.66) | 10.6 (0.94) |

| CV risk factorsb, n (%) | ||

| n | 177 | 39 |

| Any CV risk factor | 166 (94) | 38 (97) |

| Hypertension | 160 (90) | 37 (95) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 85 (48) | 20 (51) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 62 (35) | 18 (46) |

| Angina pectoris | 13 (7) | 2 (5) |

Intent-to-treat population.

Safety population.

Low rhEPO dose: <100 IU/kg/week epoetin or <0.5 μg/kg/week darbepoetin; high rhEPO dose: ≥100 IU/kg/week epoetin or ≥0.5 μg/kg/week darbepoetin.

BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; ITT, intent-to-treat; IU, international unit; rhEPO, recombinant human erythropoietin; SD, standard deviation.

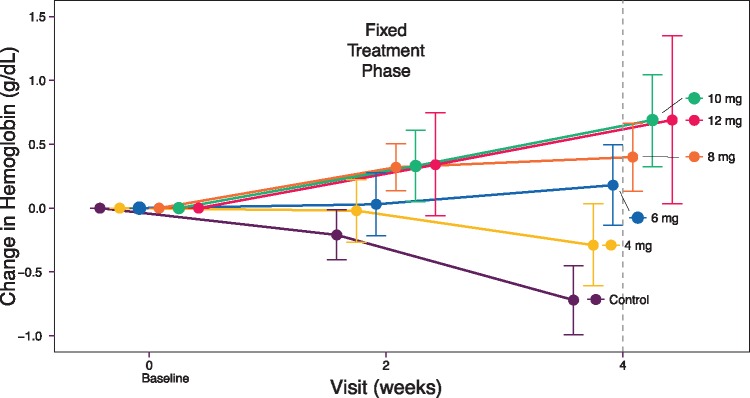

Hemoglobin dose–response

At baseline, mean hemoglobin across the daprodustat and control groups was 10.4 g/dL (individual group means ranged from 10.3 to 10.6 g/dL). Over the 4-week fixed-dose treatment phase, daprodustat doses up to 10 mg once daily produced a dose-dependent change in hemoglobin from baseline (12 mg produced similar responses to 10 mg), with changes evident at Week 2; hemoglobin decreased in the control group receiving placebo (Figure 2, Supplementary data, Table S2, Item S6).

FIGURE 2:

Mean change in hemoglobin levels from baseline to Week 4 by treatment group [intent-to-treat (ITT) population].

The dose–response model-based analysis estimated that a dose of 4.4 mg of daprodustat would produce a 0 mg/dL change in hemoglobin over 4 weeks after switching from rhEPO and that a dose of 0.42 mg would be the minimally effective dose (i.e. −0.5 g/dL change from baseline). (Additional outputs of the model are provided in the Supplementary data, Item S6.)

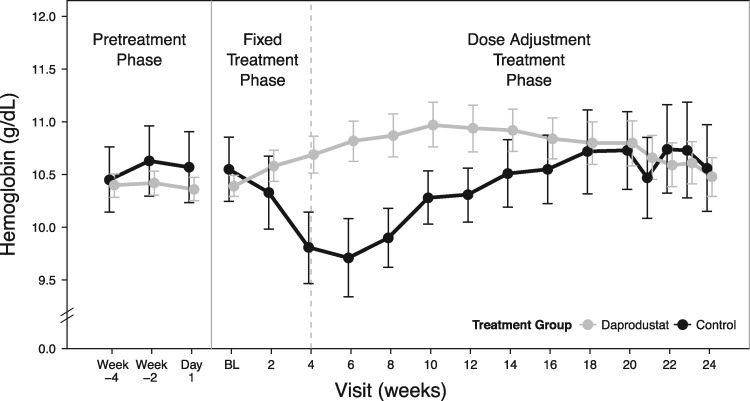

Change in hemoglobin levels over time

After the fixed-dosing phase, when doses were titrated to achieve the hemoglobin target range (10–11.5 g/dL), hemoglobin levels for those receiving daprodustat (combining all starting doses) converged toward the hemoglobin target. In the control group, hemoglobin levels returned to baseline by Week 14 after restarting rhEPO at Week 4 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3:

Mean hemoglobin levels over 24 weeks by combined daprodustat groups versus controls [intent-to-treat (ITT) population]. BL, baseline.

At Week 24, the mean ± standard deviation (SD) hemoglobin change from baseline was 0.03 ± 1.05 g/dL for the daprodustat group and −0.11 ± 1.43 g/dL for the control group, with 58% of participants in each group having hemoglobin values within the target range. The median percentage of time within the hemoglobin target range over the last 4 study weeks was 60% for the daprodustat group and 66% for the control group. A sensitivity analysis of the percentage of time within, above and below the hemoglobin target range between Weeks 20 and 24 is shown in Supplementary data, Table S3, Item S6. The median final dose of daprodustat was 6 mg and the median final rhEPO dose, standardized to IV epoetin, was 55.8 U/kg/week.

Two (1%) participants in the combined daprodustat group met protocol-defined hemoglobin stopping criteria (<7.5 g/dL). Hemoglobin levels ≥13 g/dL were observed in 17 (10%) participants in the combined daprodustat group, with 82% occurring in those randomized to starting doses ≥8 mg. Hemoglobin levels ≥13 g/dL were observed in one (3%) participant in the control group. Few participants in either group received red blood cell (RBC) transfusions during the study [7 (4%) combined daprodustat; 2 (5%) control], with acute bleeding being the most common reason.

The changes in hemoglobin were associated with expected changes in hematocrit, RBC count and absolute reticulocyte count (Supplementary data, Table S4, Item S7).

Erythropoietin and VEGF levels

Baseline plasma EPO levels were similar across the daprodustat and control groups. The median maximum observed EPO level was 36.5 IU/L for the combined daprodustat group and 522.9 IU/L for the control group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Levels and change from baseline for EPO and VEGF (ITT population)

| Combined daprodustat | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 171) | (n = 39) | |

| EPO levels (IU/L) | ||

| Baselinea | ||

| n | 163 | 36 |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 9.2 (2.5, 755.8) | 9.3 (2.6, 54.6) |

| Maximum observed EPO levelb, median (minimum, maximum) | 36.5 (5.2, 1379.3) | 522.9 (19.0, 51 200.0) |

| Maximum observed CFB in EPO levelb, median (minimum, maximum) | 27.1 (−724.5, 1371.6) | 512.9 (5.3, 51 195.4) |

| VEGF levels (ng/L) | ||

| Baselinea | ||

| n | 163 | 36 |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 186.9 (64.3, 1142.6) | 220.0 (78.2, 595.7) |

| Maximum observed VEGFb median (minimum, maximum) | 270.0 (81.8, 808.3) | 269.4 (98.7, 924.0) |

Baseline is the last predose value.

Measurements in the daprodustat group were done predose and postdose 6–15 h after dosing; measurement in the control group was performed ∼5–15 min after dosing with rhEPO.

CFB, change from baseline; EPO, erythropoietin; ITT, intent-to-treat; IU, international units; rhEPO, recombinant human erythropoietin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Across the treatment and control groups, plasma VEGF levels were similar at baseline (Table 3). VEGF levels were highly variable at all time points, with no clear signal for a change in any treatment group (Table 3).

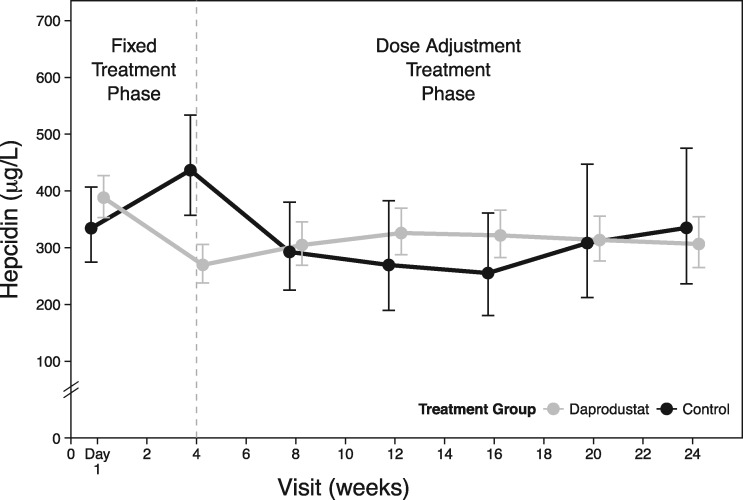

Measures of iron metabolism and IV iron use

Mean baseline levels in hepcidin and other iron parameters were similar across the treatment and control groups (Table 4). Hepcidin levels decreased for participants in the daprodustat group over the first 4 weeks and remained below baseline for the combined daprodustat group throughout the treatment phase (Figure 4, Table 4). Participants in the control group had an initial increase in hepcidin while on placebo, and once rhEPO was restarted at Week 4, mean hepcidin levels decreased over time and approached baseline by the end of treatment. (Results for other iron parameters are provided in Table 4 and Supplementary data, Figure S2, Item S8.)

Table 4.

Changes from baseline for markers of iron metabolism (ITT population)

| Combined daprodustat (n = 171) |

Control (n = 39) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | % CFB at Week 24 | Baseline | % CFB at Week 24 | |

| Hepcidin (µg/L) | ||||

| n | 171 | 114 | 38 | 32 |

| Geometric mean | 388.2 | –20.6 | 334.4 | 3.6 |

| 95% CI | 352.9, 427.1 | –29.9, –10.0 | 274.7, 407.1 | –20.4, 34.9 |

| TSAT (%) | ||||

| n | 171 | 115 | 39 | 32 |

| Geometric mean | 29.6 | –4.4 | 30.7 | –9.0 |

| 95% CI | 27.9, 31.5 | –11.2, 2.8 | 27.0, 35.0 | –27.3, 13.9 |

| Baseline | CFB at Week 24 | Baseline | CFB at Week 24 | |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | ||||

| n | 171 | 115 | 39 | 33 |

| Mean | 585.1 | −59.9 | 459.0 | 56.8 |

| SD | 429.7 | 331.8 | 261.0 | 214.3 |

| TIBC (µmol/L) | ||||

| n | 171 | 115 | 39 | 32 |

| Mean | 41.6 | 5.5 | 41.2 | −2.0 |

| SD | 6.6 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 4.5 |

| Total iron (µmol/L) | ||||

| n | 171 | 115 | 39 | 33 |

| Mean | 13.4 | 0.9 | 13.4 | −0.8 |

| SD | 6.1 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 7.6 |

CFB, change from baseline; CI, confidence interval; TIBC, total iron-binding capacity; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

FIGURE 4:

Mean hepcidin levels over 24 weeks by combined daprodustat groups versus controls [intent-to-treat (ITT) population].

Approximately 67% of participants in both the treatment and control groups were receiving IV iron at baseline. During the treatment phase, the median IV iron dose, adjusted by exposure, was similar (44.1 versus 42.7 mg/week) for the daprodustat and control groups, respectively.

Safety

The overall incidence of any AEs through the 24-week treatment phase was similar in the combined daprodustat and control groups (Table 5). Of the AEs most frequently reported, diarrhea, nausea, hypertension and hyperkalemia were reported more often in the combined daprodustat group, while nasopharyngitis and back pain were reported more often in the control group. While hyperkalemia was reported as an AE more frequently in the daprodustat group than in the control group (Table 5), the proportion of hyperkalemia events of potential clinical importance (potassium >6.3 mmol/L) was slightly higher in the control group (17%) than in the daprodustat group (14%).

Table 5.

AEs and frequency of MACE and component end points in the combined daprodustat and control groups (safety population)

| Combined daprodustat | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 177) | (n = 39) | |

| AEs occurring in ≥5% of participants | ||

| Any event, n (%) | 129 (73) | 31 (79) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (9) | 2 (5) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 15 (8) | 5 (13) |

| Nausea | 13 (7) | 0 |

| Headache | 9 (5) | 2 (5) |

| Hypertension | 9 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Hyperkalemia | 8 (5) | 0 |

| Back pain | 7 (4) | 4 (10) |

| MACE composite endpointsa, n (%) | ||

| Any MACEb | 7 (4) | 0 |

| Any MACE+c | 10 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Components of composite endpointsd, n (%) | ||

| All-cause mortality | 5 (3) | 0 |

| MI (fatal or nonfatal) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Stroke (fatal or nonfatal) | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalization due to heart failure | 5 (3) | 1 (3) |

Cardiovascular events, including MACEs, defined as MI, stroke or death, were collected but were not formally adjudicated.

A MACE is defined as a first occurrence of all-cause mortality, a nonfatal MI or a nonfatal stroke.

A MACE+ is defined as a first occurrence of a MACE or hospitalization due to heart failure.

Includes all events.

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MI, myocardial infarction.

Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported in 31 (18%) participants in the combined daprodustat group and in 10 (26%) participants in the control group. The most common SAEs in the combined daprodustat group were acute myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac arrest, in three participants each, followed by unstable angina, cardiac failure, hypertensive crisis, lobar pneumonia and pulmonary edema in two participants each. All other SAEs were reported in one participant each. In the control group, no specific SAE was reported in more than one participant. A summary of cardiovascular events, including major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and component endpoints, are summarized in Table 5. Other preidentified AEs of interest are described in the Supplementary data, Item S9.

Mean baseline and absolute changes in left ventricular ejection fraction and estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) were similar for the daprodustat and control groups (Supplementary data, Table S5, Item S9). An increase of >20 mmHg from baseline in estimated sPAP was observed in eight (7%) participants in the combined daprodustat group and in no participants in the control group.

Mean changes from baseline in blood pressure (BP) for the combined daprodustat and control groups are presented in Table 6. Although the mean change from baseline in systolic BP was greater in the control group than the combined daprodustat group by ∼5 mmHg, more participants in the combined daprodustat group [22 (12%)] had an increase in the number of antihypertensive medications relative to the control group [2 (5%)].

Table 6.

Summary of SBP and DBP at Week 24 (ITT population)

| Combined daprodustat | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 171) | (n = 39) | |

| SBP (mmHg) | ||

| Baselinea | ||

| n | 163 | 36 |

| Mean (SD) | 141.5 (17.4) | 139.5 (18.7) |

| Change from baseline at Week 24 | ||

| n | 112 | 31 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (18.0) | 5.6 (19.3) |

| DBP (mmHg) | ||

| Baselinea | ||

| n | 163 | 36 |

| Mean (SD) | 74.9 (12.6) | 75.5 (11.9) |

| Change from baseline at Week 24 | ||

| n | 112 | 31 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.3 (9.7) | 1.3 (11.5) |

Baseline is the last predose value.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

No adverse trends were noted for clinical laboratory values and electrocardiogram parameters. Furthermore, no changes were seen in visual acuity or intraocular pressure based on the protocol-specified ophthalmology exams (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study is the largest and longest completed to date in the HD population switched from rhEPO to treatment with the HIF-PHI, daprodustat. Over the first 4 weeks, daprodustat produced dose-dependent changes in hemoglobin up to the 10-mg dose, with dose separation noted as early as the first assessment at 2 weeks. These increases in hemoglobin were associated with the expected increase in absolute reticulocyte count, thus supporting increased erythropoiesis as the main driver for daprodustat’s effect on hemoglobin.

Over the 24-week treatment phase, daprodustat maintained hemoglobin levels, with 2 (1%) participants requiring permanent discontinuation of study medication (hemoglobin <7.5 g/dL). Although 17 (10%) participants on daprodustat required a dose interruption for hemoglobin ≥13 g/dL, this was influenced by the random starting dose allocation, as most excursions occurred with starting doses ≥8 mg. The proportion of participants on daprodustat who were within the hemoglobin target range (58%) at Week 24 is lower than that observed in a recently conducted 24-week study in participants with CKD and could be due to participants in this study being assigned to random starting doses (2–12 mg). In the CKD study, starting doses were assigned based on salient baseline parameters (74% in the target range at Week 24; [31]).

In the daprodustat group, hemoglobin was maintained with postdose plasma EPO levels similar to those observed during acclimatization to high altitude [19]. In contrast, maximum observed postdose EPO levels in the control group were 14-fold higher than in the daprodustat group, a finding consistent with prior daprodustat clinical studies [13]. If higher EPO levels contribute to the cardiovascular risk associated with rhEPO [20], then daprodustat may provide a safer cardiovascular risk profile.

Consistent with findings from prior trials with daprodustat and vadadustat [13, 14, 21], in this 24-week study, daprodustat, as well as the control, had minimal if any effect on VEGF, a known target gene of HIF [22–24]. This is consistent with preclinical work demonstrating that VEGF expression is less sensitive to HIF activation than is EPO expression (GlaxoSmithKline, unpublished data) [25].

Participants were iron replete at baseline and an iron protocol provided thresholds for IV iron use to ensure participants remained replete. Decreases in hepcidin, ferritin and TSAT and increases in total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) during the initial 4-week, fixed-dose phase corresponded with the increases in hemoglobin observed across the daprodustat doses studied, which is similar to findings reported with other HIF-PHIs [10, 26]. The decrease in ferritin and TSAT and increase in TIBC are consistent with iron utilization due to increased erythropoiesis, and the decreased hepcidin could be an effect of the resultant decreased iron availability. The continued suppression of hepcidin and ferritin observed for the remainder of the trial in participants on daprodustat may reflect iron stores that remained lower than baseline with daprodustat [27]. Although no difference in IV iron administration between treatment groups was observed, the interpretation of data is confounded since many participants continued IV iron despite exceeding the prespecified iron protocol stopping thresholds, and the study duration may have been insufficient to deplete iron stores to the point of elucidating a difference between treatments. Further work remains to understand the effects of daprodustat on iron metabolism and the resultant effects on IV iron requirements; these are being tested in a current Phase 3 trial (NCT03029208).

Treatment with daprodustat for up to 24 weeks demonstrated an AE profile consistent with the complex medical histories and cardiovascular comorbidities typical of this patient population. MACEs occurred more frequently in the daprodustat group, but these events were underpowered and not adjudicated, so definitive conclusions cannot be made. A long-term cardiovascular outcome study is ongoing to conclusively assess these associations. No emerging safety concerns based on the collective safety data, nor safety signals for any preidentified AE of interest, were identified for daprodustat.

An imbalance was also reported for the number of participants with a >20 mmHg increase from baseline in estimated sPAP for the daprodustat group relative to controls, despite mean absolute changes from baseline in estimated sPAP being similar for both groups. This finding was not dose related. Changes in fluid status could not be ruled out as a confounder, given that the timing of echocardiograms (ECHOs) relative to dialysis day was inconsistent both within a given participant and between participants in the daprodustat and control groups. In a 24-week study in participants with CKD, who are less prone to fluid shifts as compared with participants on HD, there was no difference in estimated sPAP elevations >20 mmHg in those receiving daprodustat compared with controls [31]. Additionally, dedicated preclinical data (GlaxoSmithKline, unpublished data) and a clinical study in healthy volunteers [28] demonstrated no effect of daprodustat on peak right ventricular pressure or sPAP, respectively, even in the setting of a hypoxic challenge.

Treatment with daprodustat did not raise BP. Consistent with the known AEs of rhEPO [29], the control group had an increase in systolic BP at Week 24. Interpretation of the collective BP data is complicated by a greater proportion of participants on daprodustat reporting AEs of hypertension and having an increase in the number of antihypertensive medications relative to control. These imbalances may be due to more careful monitoring of BP in the combined daprodustat group, given it is an investigational drug, and underreporting of events in the control arm, given the known AE of hypertension with rhEPO.

Limitations of this trial include an uneven randomization ratio (4.5:1) resulting in a relatively small control group (n = 39) and the open-label design from Week 4 onward. Additionally, the tight eligibility criteria limit the generalizability of the findings, and the degree of noncompletion and large number of secondary outcomes complicates interpretation of the results. The open-label design could potentially influence how AEs are reported by participants or recorded by study staff for an investigational medication as compared with the standard of care. For example, more AEs of hyperkalemia were reported in the daprodustat group than in the control group, despite the fact that more hyperkalemia events of potential clinical importance were reported in the control group. This kind of bias may also have been true for the excess reports of nausea with daprodustat compared with controls. Nausea is common in patients on dialysis [30]. More AEs of nausea reported in the daprodustat group could have been influenced by daprodustat being an investigational medication or the oral route of daprodustat administration. Cardiovascular events were not formally adjudicated and the study was not powered for any formal assessment of cardiovascular events. Lastly, the timing of the ECHO assessment relative to HD was not standardized and specific data to determine fluid shifts and estimated dry weight were not collected.

Overall, these data demonstrate that daprodustat produced dose-dependent changes from baseline in hemoglobin over the first 4 weeks and, with the dose-adjustment rules applied in this trial, daprodustat effectively achieves and maintains hemoglobin target levels after switching from a stable dose of rhEPO. This efficacy was achieved while maintaining effective plasma EPO levels and an AE profile consistent with that of the patient population. These data support continued development of daprodustat to treat anemia of CKD in patients receiving dialysis, including an ongoing large-scale cardiovascular outcomes trial (ASCEND-D) in patients receiving maintenance dialysis who are switching from rhEPO and its analogs (NCT02879305) and a trial in patients who are initiating dialysis (NCT03029208) to assess the safety and efficacy of daprodustat.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the investigators and their staff for their contributions (see ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01977482 for the site list). The authors acknowledge the following GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) employees for their assistance with study management and critical review: Deborah Kelly, MD, and Douglas Wicks, MPH, CMPP. Authors meet the authorship criteria set forth by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Medical editorial support (Nancy Price, PhD, Gautam Bijur, PhD, and Sarah Hummasti, PhD) and graphic services were provided by AOI Communications and were funded by GSK. B.M.J. was previously affiliated with Clinical Pharmacology Modeling and Simulation, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

FUNDING

Funding for this study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01977482; EudraCT: 2013-002682-19; GSK PHI113633) was provided by GlaxoSmithKline.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The concept and study were designed by A.M.M., B.C., L.H., N.B., B.M.J., J.J.L. and A.R.C. A.K.N. and M.A. were in charge of data acquisition. Statistical analysis was conduted by N.B. and D.J. All authors reviewed the analysis and interpreted the data. A.M.M. wrote the initial draft and each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript development and revision. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A.M.M., B.C., N.B., D.J., J.J.L. and A.R.C. are employees of and hold stock in GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). L.H. and B.M.J. are former employees of GSK and hold stock options in GSK. A.K.N. received research grants from GSK and research sponsorship from Affymax. M.A. has no potential conflicts of interest to report. This manuscript is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract form. Some of the data included in the present article were presented at the American Society of Nephrology meeting in Chicago, IL, USA, 15–20 November 2016.

REFERENCES

- 1. United States Renal Data System. 2013 Atlas of CKD and ESRD. Clinical indicators and preventive care https://www.usrds.org/2013/pdf/v2_ch2_13.pdf (3 February 2017, date last accessed)

- 2. Babitt JL, Lin HY.. Mechanisms of anemia in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 1631–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Locatelli F, Del Vecchio L.. New strategies for anaemia management in chronic kidney disease. Contrib Nephrol 2017; 189: 184–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK. et al. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 584–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N. et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2071–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen C-Y. et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 2019–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL. et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2085–2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jenkins J. Statement regarding erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) before the Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Health, US House of Respresentatives. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg49981/pdf/CHRG-110hhrg49981.pdf. Published 26 June 2007. (20 December 2017, date last accessed)

- 9. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: modified dosing recommendations to improve the safe use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) in chronic kidney disease. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm259639.htm. Published 24 June 2011 (21 March 2017, date last accessed)

- 10. Besarab A, Chernyavskaya E, Motylev I. et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592): correction of anemia in incident dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 1225–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Provenzano R, Besarab A, Sun CH. et al. Oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor roxadustat (FG-4592) for the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11: 982–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brigandi RA, Johnson B, Oei C. et al. PHI: a novel hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (GSK1278863) for anemia in CKD: a 28-day, phase 2A randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67: 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holdstock L, Meadowcroft AM, Maier R. et al. Four-week studies of oral hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor GSK1278863 for treatment of anemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 1234–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pergola PE, Spinowitz BS, Hartman CS. et al. Vadadustat, a novel oral HIF stabilizer, provides effective anemia treatment in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016; 90: 1115–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Keith B. et al. HIF-2α, but not HIF-1α, promotes iron absorption in mice. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 1159–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu Q, Davidoff O, Niss K. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates hepcidin via erythropoietin-induced erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 4635–4644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mason-Garcia M, Beckman BS, Brookins JW. et al. Development of a new radioimmunoassay for erythropoietin using recombinant erythropoietin. Kidney Int 1990; 38: 969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ. et al. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 1993; 69: 236–239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Milledge JS, Cotes PM.. Serum erythropoietin in humans at high altitude and its relation to plasma renin. J Appl Physiol 1985; 59: 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK. et al. Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin-α dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int 2008; 74: 791–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akizawa T, Tsubakihara Y, Nangaku M. et al. Effects of daprodustat, a novel hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor on anemia management in Japanese hemodialysis subjects. Am J Nephrol 2017; 45: 127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goel HL, Mercurio AM.. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 871–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karuppagounder SS, Ratan RR.. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibition: robust new target or another big bust for stroke therapeutics? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1347–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nitta K, Uchida K, Kimata N. et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor release by glomerular endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 1999; 373: 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flamme I, Oehme F, Ellinghaus P. et al. Mimicking hypoxia to treat anemia: HIF-stabilizer BAY 85-3934 (Molidustat) stimulates erythropoietin production without hypertensive effects. PLoS One 2014; 9: e111838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Provenzano R, Besarab A, Wright S. et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592) versus epoetin alfa for anemia in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a phase 2, randomized, 6- to 19-week, open-label, active-comparator, dose-ranging, safety and exploratory efficacy study. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67: 912–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ashby DR, Gale DP, Busbridge M. et al. Plasma hepcidin levels are elevated but responsive to erythropoietin therapy in renal disease. Kidney Int 2009; 75: 976–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Demopoulos L, Haws T, Mahar K. et al. Lack of correlation between PK and changes in pulmonary artery systolic pressure in healthy volunteers following administration of the HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor, GSK1278863. Pharmacotherapy 2014; 34: e222 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krapf R, Hulter HN.. Arterial hypertension induced by erythropoietin and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4: 470–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Asgari MR, Asghari F, Ghods AA. et al. Incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting in a group of maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Renal Inj Prev 2017; 6: 49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holdstock L, Cizman B, Meadowcroft AM. et al. Daprodustat for anemia: a 24-week, open-label, randomized controlled trial in participants with chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J 2019; 12: 129–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.