Abstract

Purpose:

The number of targeted oral anticancer medications (TOAMs) has grown rapidly in the past decade. The high cost of TOAMs raises concerns about the financial aspect of treatment, especially for patients enrolled in Medicare Part D plans because of the coverage gap.

Methods:

We identified patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who were new TOAM users from the SEER registry data linked with Medicare Part D data, from years 2007 to 2012. We followed these patients throughout the calendar year when they started taking the TOAMs and examined their out-of-pocket (OOP) payments and gross drug costs, taking into account their benefit phase, plan type, and cost share group.

Results:

We found that 726 (81%) of the 898 patients with CML who received TOAMs had reached the catastrophic phase of their Medicare Part D benefit within the year of medication initiation, with a large majority of patients reaching this phase in less than a month. Patients without subsidies showed a clear pattern of a spike in OOP payments when they began treatment with TOAMs. The OOP payment for patients with subsidies was substantially lower. The monthly gross drug costs were similar between patients with and without subsidies.

Conclusion:

Patients experience quick entry and exit from the coverage gap (also called the donut hole) as a result of the high price of TOAMs. Closing the donut hole will provide financial relief during the initial month(s) of treatment but will not completely eliminate the financial burden.

INTRODUCTION

The Medicare prescription drug benefit program (also known as Medicare Part D) was launched in 2006 and has a complex insurance design. The original standard Part D plan includes the following four phases: a deductible phase, an initial coverage phase with copayment and coinsurance, a coverage gap phase (commonly known as the donut hole) in which patients pay 100% of the drug cost, and a catastrophic coverage phase with coinsurance substantially reduced to approximately 5%. The lack of insurance coverage during the donut hole phase has triggered substantial concern in the health care community, especially for patients who are taking expensive prescription drugs.1 Consequently, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act includes a provision to gradually close the coverage gap by 2020.2

For Part D beneficiaries, a wide variation in their out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses for prescription drugs occurs throughout the year during the various plan phases. This variation in the price of prescription drugs has sparked abundant research in the literature, because the coverage gap phase complicates patients’ drug purchase decisions. To make financially optimal decisions, forward-looking patients will take future drug spending into consideration when making decisions regarding whether and when to fill or refill medications. Several studies have shown that patients tend to use fewer medications in the later months of a plan year or when they are close to the donut hole of Medicare Part D plans.3-5 Of note, these studies tended to focus on Part D beneficiaries who were taking medications that were substantially less expensive than targeted oral anticancer medications (TOAMs).

The number of targeted therapies for cancer has grown rapidly in the past decade.6 The growth in the development and use of TOAMs has been especially striking; the proportion of patients with cancer treated with TOAMs had grown from less than 2% in 2001 to 14% in 2011.7 In addition, the monthly cost of TOAMs more than doubled in the last decade, increasing from approximately $3,400 per month in 2001 to about $7,400 in 2011. With rapid developments in the design and production of novel TOAMs, the number of patients with cancer taking these expensive medications will continue to grow.8

The objective of our study was to examine the financial burden of TOAMs for the Medicare Part D program and its beneficiaries. Using a cohort of patients with CML, our research described patient behavior with respect to the donut hole and the costs for patients and the Medicare Part D program. We focused on patients with CML because TOAMs have become the standard of care for the treatment of CML.

METHODS

Data Source

We used SEER registry data linked with 2007 to 2012 Medicare Part D data for this study. SEER-Medicare data provide detailed information on patients’ demographics, tumor characteristics, and outpatient prescription insurance coverage, utilization, and costs.

Study Cohort

We selected patients diagnosed with CML based on the SEER registry information and limited our study sample to patients who were new users of any of the three TOAMs (imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib) that were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of CML during our study period (2007 to 2012). We imposed a 6-month washout period before the first TOAM prescription date to ensure that patients were first-time TOAM users. We followed the patients’ prescriptions of TOAMs chronologically during the calendar year in which they first became TOAM users. We required patients to have continuous enrollment in Medicare Part D during the calendar year of observation, as well as the washout period, to ensure the completeness of prescription drug claims. The final study cohort consisted of 898 patients for analysis in this study.

Study Variables

The Part D claims data include information on the benefit phase associated with each Part D claim. Using that information, we characterized benefit design using the two variables; the first was a binary variable indicating whether the patients ever reached the catastrophic phase (ie, if they had at least one claim indicating catastrophic coverage during the first calendar year of TOAM therapy), and the second variable was the number of days from the first TOAM prescription until the catastrophic phase was reached. We calculated the number of days to reach catastrophic coverage as the difference between the date of the first TOAM prescription and the date of the first Part D claim demonstrating catastrophic phase entry.

We quantified costs using two measures—patients’ OOP payments and gross drug costs, which included ingredient costs, dispensing fees, and total amount attributed to sales tax. We calculated the cumulative costs of all prescription drug claims from January 1 (ie, the beginning of a new Part D benefit cycle) of the year the patient started TOAM therapy until the first drug claim indicative of reaching catastrophic coverage. We calculated OOP payments and gross drug costs for each calendar month by summing up costs associated with all drug claims prescribed in that month. Further, to understand the financial burden to patients caused specifically by TOAMs, we calculated OOP payments per 30-day supply by dividing the sum of OOP payments for all TOAM claims by the total number of days’ supply aggregated over these claims. All costs were adjusted for inflation to 2014 dollars based on the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

To better understand whether the financial burden of targeted oral therapies differ by Part D plan characteristics, we performed two subgroup analyses. First, we categorized patient plan type into the following two groups: traditional stand-alone Part D plan or managed care organization or regional preferred provider organization. Second, we subdivided patients into the following three cost share categories based on their subsidy and copayment status: heavily subsidized (100% premium subsidy with no or low copayment), moderately subsidized (some premium subsidy and copayment), and no subsidy. We then compared OOP payment per 30-day TOAM supply according to the two plan subgroups. We used χ2 tests to examine whether there were significant group differences in OOP cost quartiles.

RESULTS

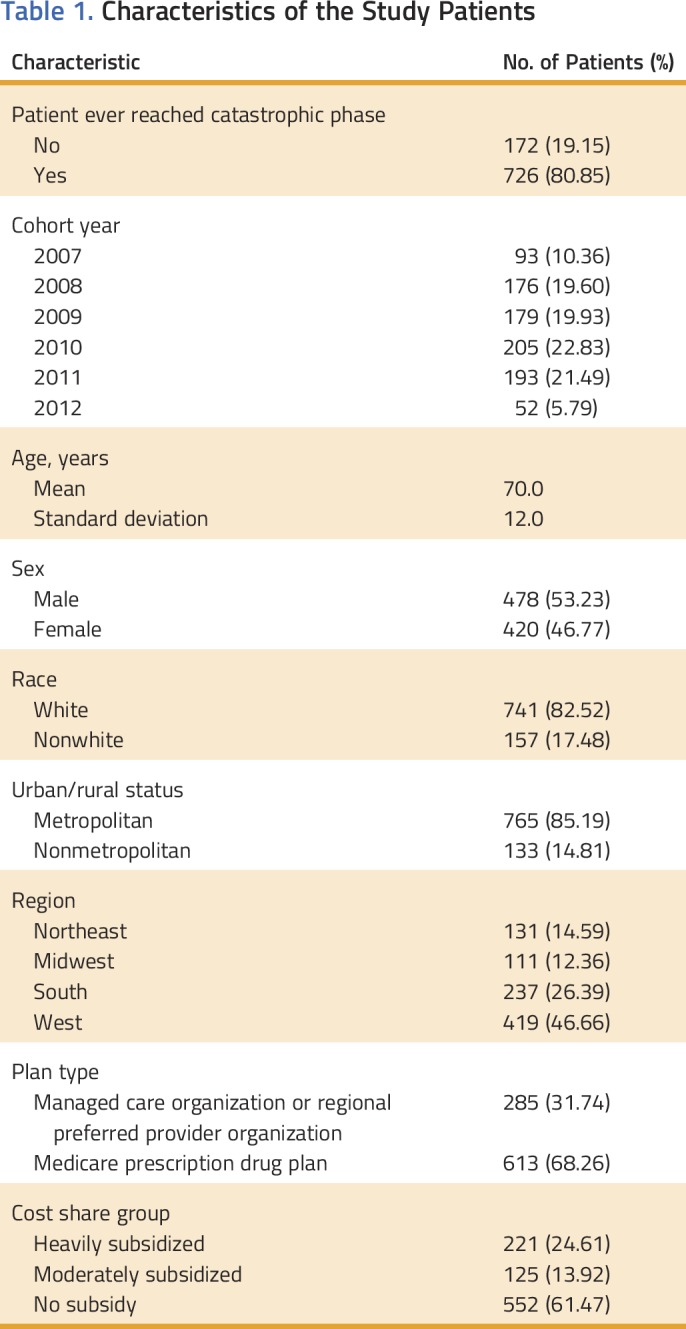

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the study cohort. Of the 898 patients with CML who received TOAMs, 726 (81%) had reached the catastrophic phase within the first year of medication initiation. The mean patient age was 70 years, approximately half of patients (47%) were women, the majority (83%) were white, and 68% of the patients had traditional stand-alone Part D prescription plans. Although many patients (61%) did not have any subsidies, a quarter of the patients were heavily subsidized.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Patients

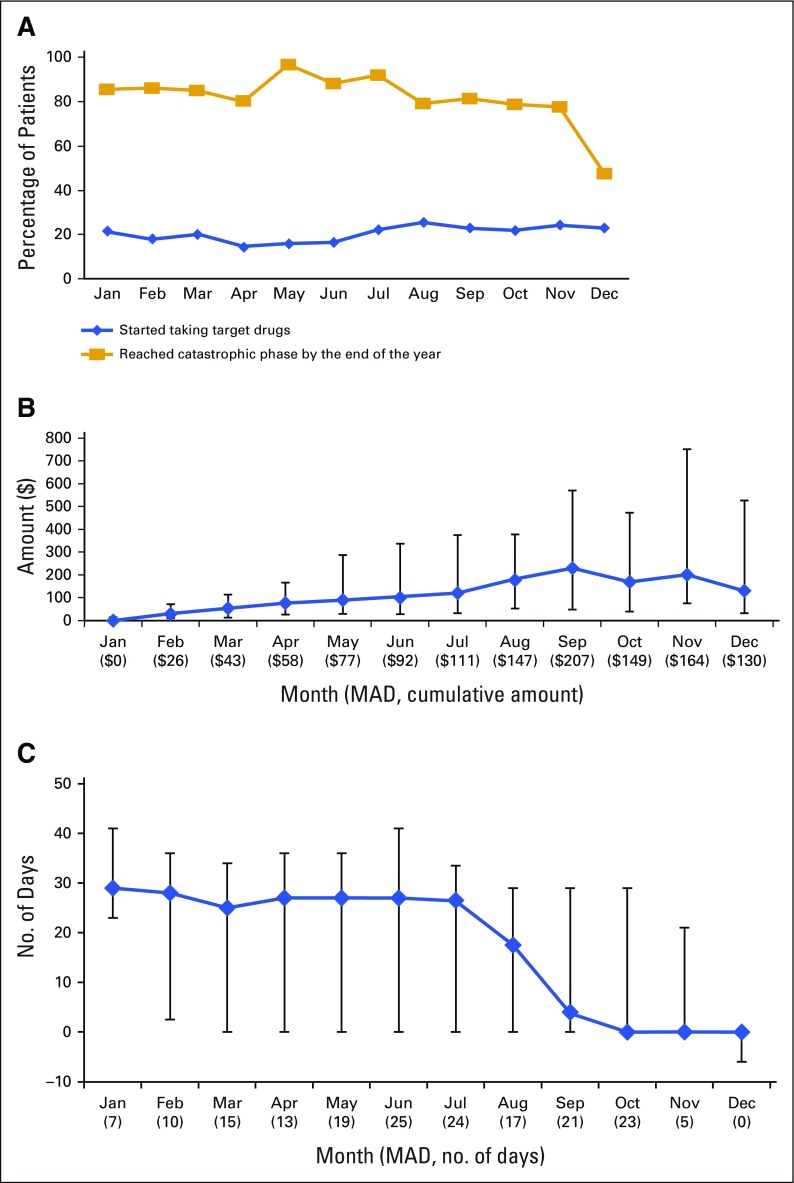

In Figure 1, we stratified patients by the calendar month of their first prescription of a TOAM (referred to as starting month of TOAM hereafter). Figure 1A presents the percentage of patients starting TOAMs generated by dividing the number of patients who started TOAMs by the number of patients with CML diagnosed in each month and the percentage of patients reaching the catastrophic phase by the end of the year. It shows that the number of patients who started taking TOAMs did not show higher uptake of the drugs in the earlier months of the year compared with later months, suggesting that the nonlinearity in the pricing design in Part D plans did not seem to affect TOAM use among patients with CML. It also illustrates that the percentage of patients reaching the catastrophic phase within the first calendar year of their treatment initiation remained at or greater than 80% throughout the year except for patients who started TOAMs in December, when the percentage decreased to 47%. Figure 1B shows that patients who started later in the year had incurred higher OOP payments before starting TOAMs. The trend was significant, with a Spearman rank-order correlation of 0.41 (P < .001). Figure 1C demonstrates a downward trend (Spearman rank-order correlation, −0.36; P < .001) in the median number of days for patients to reach the catastrophic phase depending on their starting month of TOAM. This is probably because they had already accumulated a considerable amount of OOP expenses from other prescription drugs that were consumed before starting TOAMs, as shown by Figure 1B.

FIG 1.

(A) Percentage of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who started targeted oral anticancer medications (TOAMs) by month and percentage of patients who reached the catastrophic phase by starting month of TOAMs among those who started TOAMs. (B) Median, interquartile range, and median absolute deviation (MAD) of cumulative amount patients spent on other prescription drugs before starting TOAMs by starting month of TOAMs. (C) Median number, interquartile range, and MAD of days from the start of TOAM until reaching the catastrophic phase by targeted drug starting month (among patients who reached catastrophic phase) For patients who started in October, November, and December and reached catastrophic phase by the end of the year, the median number of days was 0 and the interquartile range even reached negative numbers for December, indicating that they had already reached catastrophic phase before initiating their TOAMs as a result of spending on other prescription drugs.

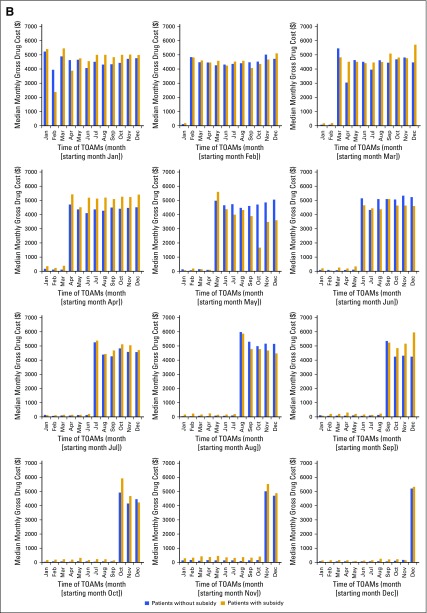

We also examined the month-by-month OOP costs and gross drug costs stratified by subsidy status and starting month of TOAM. Appendix Figure A1A (online only) showed a clear pattern of a spike in the monthly OOP payment for patients without subsidies during the month when the patients started TOAM therapy. Afterward, the OOP payment quickly decreased and, within 2 to 3 months, became stabilized at approximately $200 per month, which is approximately 10% of the spike value. In contrast, the OOP payment for patients with subsidies was substantially lower. Appendix Figure A1B (online only) shows that monthly gross drug costs increased sharply on the starting month and remained high afterward; these costs did not differ much between patients with and without subsidies.

We further examined patient OOP payments and gross drug costs for a 30-day supply of TOAMs averaged over all fills in the year. Interestingly, we observed a wide variation in OOP payments. The median OOP payment was $183 per 30-day supply of TOAMs; more than 25% of patients paid less than $2, whereas the top quartile paid more than $912. The distribution of gross drug costs per 30-day supply was not as skewed as that of the OOP payment histogram, with the majority of patients falling between $3,632 (10th percentile) and $8,429 (90th percentile).

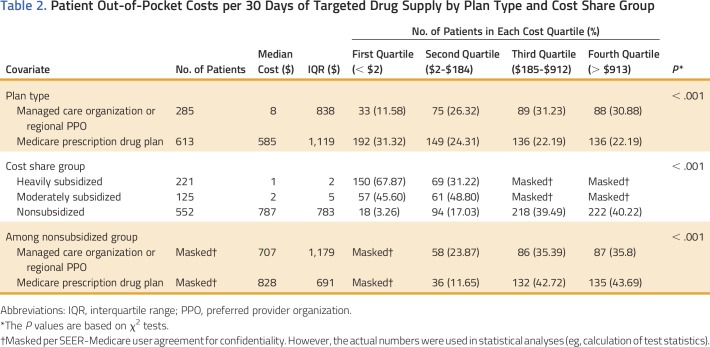

Table 2 lists the results from subgroup analyses of OOP payments per 30-day supply of TOAMs, in which significant differences were observed based on plan type and cost share group. Patients with traditional stand-alone Part D plans had higher OOP costs per 30-day supply compared with managed care organizations and regional preferred provider organizations. As expected, OOP payments for patients with subsidies were much lower, with small percentages of patients in the heavily and moderately subsidized groups paying more than $184 (the median) for a 30-day supply. In contrast, 80% of patients without subsidies incurred OOP payments higher than $184 per 30-day supply; more than 40% of patients in this group paid more than $913.

Table 2.

Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs per 30 Days of Targeted Drug Supply by Plan Type and Cost Share Group

DISCUSSION

Over the past 15 years, there has been a rapid growth in the development and approval of TOAMs for the treatment of a variety of cancers. Given the high costs of these specialty drugs, their rapid adoption in cancer treatment has imposed substantial financial burdens to the health care system and especially Medicare, because cancer prevalence is much higher among the elderly.9-13 Many studies have shown that higher OOP costs for patients negatively affect drug adherence,14-18 although the demand elasticity for specialty cancer drugs is relatively low compared with other prescription drugs.19-21

In this article, we focused on the financial burden for Medicare Part D enrollees taking TOAMs for CML, a cancer type that has benefited substantially from TOAM therapy. We found that the vast majority of patients who received TOAMs reached the catastrophic phase of the Part D program in the year of treatment initiation, except for those who started TOAMs in December. Because it is possible that patients split up the last fill to provide only the supply needed to get to the beginning of the calendar year to give credit for all fills obtained in the next year, we examined the days of supply. The median number of days of supply was 30 for all 12 months. The mean number of days of supply in December was 34.02, which is not smaller than the average over the whole year (33.45 days of supply). Therefore, it seems that physicians and patients were not splitting up the fill at the end of year. It is likely that patients who started in December did not reach the catastrophic phase because they only received one fill in that year and might have needed two fills to reach catastrophic phase. This would be consistent with Appendix Figure A1A, which shows that the OOP cost decreased in the second month after starting TOAMs and stayed reasonably stable after the third month. In addition, most patients prescribed TOAMs reached the catastrophic phase in less than 1 month after beginning treatment. This suggests that the high price of TOAMs caused patients to enter and exit the donut hole with only one prescription, subjecting patients to substantial financial burden with their first prescription of TOAMs. Subsequently, OOP payments declined substantially, whereas gross drug costs remained sizable during the TOAM treatment duration.

Studies on the financial burdens of cancer treatment have concluded that insured patients with cancer often experience a high degree of financial distress.22,23 One study found that patients had to reduce spending on food and clothing and tap into savings to defray the OOP expenses.23 We observed a wide variation in OOP payments by patients’ subsidy status. Although the majority of patients with CML (68%) with heavily subsidized Part D plans paid less than $2 for a 30-day supply of TOAMs, more than 40% of patients without subsidy incurred monthly TOAM OOP payments of greater than $900. The month-by-month pattern of OOP expenses documented in our study indicated that the financial burden was greatest for the first month of TOAM treatment, especially for patients without subsidies. The sharp spike we observed in patient OOP costs associated with initiation of TOAM therapy suggests that the first month initial OOP payment may be a substantial barrier to initiating therapy. We examined the OOP costs for the first fill and found that the median OOP costs for the first fill were $3.7 (interquartile range [IQR], $2.5), $6.9 (IQR, $0.4), and $2,309.4 (IQR, $2,503.0) among patients who were heavily subsidized, moderately subsidized, and not subsidized, respectively. This finding is in line with two recent studies24,25 on patients newly diagnosed with CML, which showed that patients with higher cost sharing had reduced initiation of therapy compared with patients with lower cost sharing. Interestingly, one of the studies25 showed that despite the differences in initiation between patients with and without subsidies, once the treatment was initiated there was no significant difference in adherence between these two groups.

It has been shown that the financial burden from cancer treatment can negatively impact the quality of life and satisfaction with care of patients with cancer.26,27 Therefore, it is important for oncologists to be aware of the subgroups of patients who have a high risk of financial distress and the juncture in their treatment continuum that is most likely to be financially stressful for patients.28,29 It is intriguing to speculate whether closing the donut hole under the Patients Protection and Affordable Care Act will provide some relief of the financial burden for patients with CML taking TOAMs. With the complete elimination of the donut hole (predicted to take place in 2020), it is expected that the sharp spike in patient monthly OOP payments will be reduced but not eliminated because patients will still need to reach a certain OOP limit to qualify for catastrophic phase coverage and will be subject to 25% coinsurance before reaching the catastrophic phase. Given the quick entry into and exit out of the donut hole as a result of the high price of TOAMs, our data revealed that patients spend the majority of their time under treatment in the catastrophic phase. Our analysis showed that, although closing the donut hole will provide some financial relief to patients during the initial month(s) of their treatment, it will not completely eliminate the financial burden to initiate treatment, and the coinsurance after reaching the catastrophic phase is still substantial, amounting to approximately $200 per month. This finding is consistent with a recent study showing that OOP costs for Medicare beneficiaries taking oral chemotherapy will remain high after the coverage gap closes.30

Despite the wide variation in patients’ OOP payments, we found that gross drug costs of TOAMs remained persistently high regardless of subsidy status. This implies that TOAMs will continue to be a huge economic burden on payers. It was reported that spending on oral oncology drugs increased from $940 million in 2006 to $1.4 billion in 2011 (in 2012 dollars).10 Meanwhile, the number of newly developed TOAMs has been growing exponentially, with FDA approval of four TOAMs in 2014 and 10 TOAMs in 2015.31 This trend is continuing at an accelerating rate, and the escalating costs present a substantial financial challenge to the health care system.32 Although a few publications have examined specialty drug cost management strategies of health care payers, no consensus plan or method of action has been formulated.33,34 Whether and how health care policies and innovative cost management strategies can help address the increasing cost challenges are important topics for future research. Some policymakers have suggested imposing a monthly OOP spending cap in Medicare Part D. The impact of such a policy change will greatly depend on the cap level. In considering the financial burden on payers, it should be taken into account that the use of TOAMs may delay or eliminate the need for transplantation, which generates cost savings. Furthermore, the use of TOAMs when patients are covered under private insurance may lead to downstream cost savings for Medicare Part A and B from avoiding transplantation when the patients become eligible for Medicare.

The FDA recently approved generic imatinib on February 1, 2016. The price difference between generic imatinib and brand name imatinib (Gleevec; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) is small; the 2016 Red Book whole acquisition annual costs are $113,650 versus $121,450, whereas the average wholesale prices are $142,000 versus $145,750 annually, respectively.35 Therefore, the availability of generic imatinib is unlikely to change the overall financial burden for 2016. It is possible that the prices may decrease further after the exclusivity period ends, but it will probably still be quite expensive for patients to initiate treatment. Further, competition for targeted cancer drugs is usually limited.36,37 It would be interesting to monitor the market and observe whether new companies join the manufacturing of generic imatinib.

This study used SEER registry data linked to Medicare Part D claims data, and therefore, it inherits some of the common limitations of observational studies. For example, unfilled prescriptions are not captured in the claims data, and therefore, we cannot identify patients who avoided initiating treatment as a result of high costs. Further studies might consider collecting information from physicians and patients on the prescription and adoption of treatment and possibly surveying patients on the potential factors that affect the initiation decision.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported in part by the Duncan Family Institute, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. R01 HS020263), and the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. R01 CA207216). This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. We acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program; National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development, and Information; the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. We thank Gary Deyter for his editorial assistance.

Appendix

FIG A1.

(A) Median monthly out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for all prescription drugs, stratified by the starting month of targeted oral anticancer medications (TOAMs). (B) Median monthly gross drug costs for all prescriptions, stratified by the starting month of TOAMs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Chan Shen, Ya-Chen Tina Shih

Collection and assembly of data: Chan Shen, Bo Zhao, Ya-Chen Tina Shih

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Financial Burden for Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Enrolled in Medicare Part D Taking Targeted Oral Anticancer Medications

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Chan Shen

Research Funding: Ipsen

Bo Zhao

No relationship to disclose

Lei Liu

Consulting or Advisory Role: Outcome Research Solutions

Ya-Chen Tina Shih

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst)

REFERENCES

- 1. Brill, JV: Trends in the prescription drug plans delivering the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. Am J Health Syst Pharm 64:S3-S6, 2007 (suppl 10) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Closing the coverage gap. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/11493.pdf [PubMed]

- 3. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00518. Aron-Dine A, Einav L, Finkelstein A, et al: Moral hazard in health insurance: Do dynamic incentives matter? Rev Econ Stat 97:725-741, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Einav L, Finkelstein A, Schrimpf P: The response of drug expenditure to non-linear contract design: Evidence from Medicare Part D. Q J Econ 130:841-899, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan C, Zhang Y. The January effect: Medication reinitiation among Medicare Part D beneficiaries. Health Econ. 2014;23:1287–1300. doi: 10.1002/hec.2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afghahi A, Sledge GW., Jr Targeted therapy for cancer in the genomic era. Cancer J. 2015;21:294–298. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shih YC, Smieliauskas F, Geynisman DM, et al. Trends in the cost and use of targeted cancer therapies for the privately insured nonelderly: 2001 to 2011. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2190–2196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felder TM, Bennett CL. Can patients afford to be adherent to expensive oral cancer drugs?: Unintended consequences of pharmaceutical development. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:(suppl 6S):64s–66s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinke JD, McGee N. Breaking the bank: Three financing models for addressing the drug innovation cost crisis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8:118–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conti RM, Fein AJ, Bhatta SS. National trends in spending on and use of oral oncologics, first quarter 2006 through third quarter 2011. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1721–1727. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch BR, Balu S, Schulman KA. The impact of specialty pharmaceuticals as drivers of health care costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1714–1720. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society of Clinical Oncology The state of cancer care in America, 2015: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:79–113. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen C, Chien CR, Geynisman DM, et al. A review of economic impact of targeted oral anticancer medications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:45–69. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.868310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Escarce JJ, et al. Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. JAMA. 2004;291:2344–2350. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huskamp HA, Deverka PA, Epstein AM, et al. The effect of incentive-based formularies on prescription-drug utilization and spending. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2224–2232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa030954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huskamp HA, Deverka PA, Epstein AM, et al. Impact of 3-tier formularies on drug treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:435–441. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2534–2542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seabury SA, Goldman DP, Maclean JR, et al. Patients value metastatic cancer therapy more highly than is typically shown through traditional estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:691–699. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: Associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298:61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman DP, Jena AB, Lakdawalla DN, et al. The value of specialty oncology drugs. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:115–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al. Patient attitudes regarding the cost of illness in cancer care. Oncologist. 2015;20:1199–1204. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, et al. High cost sharing and specialty drug initiation under Medicare Part D: A case study in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22:(suppl 4):s78–s86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4184. Winn AN, Keating NL, Dusetzina SB: Factors associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor initiation and adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 34:4323-4328, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:414–420. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:145–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: A new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:80–81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part II: How can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:253–254, 256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7736. Dusetzina SB, Keating NL: Mind the gap: Why closing the doughnut hole is insufficient for increasing Medicare beneficiary access to oral chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 34:375-380, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. CenterWatch: FDA approved drugs for oncology. https://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeutic-area/12/oncology.

- 32.Buffery D. The 2015 oncology drug pipeline: Innovation drives the race to cure cancer. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8:216–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel BN, Audet PR. A review of approaches for the management of specialty pharmaceuticals in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:1105–1114. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stern D, Reissman D. Specialty pharmacy cost management strategies of private health care payers. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12:736–744. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.9.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kantarjian H: The arrival of generic imatinib into the U.S. market: An educational event. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/may-25-2016/the-arrival-of-generic-imatinib-into-the-us-market-an-educational-event/ [Google Scholar]

- 36. Conti R: Why are cancer drugs commonly the target of schemes to extend patent exclusivity? http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/12/04/why-are-cancer-drugs-commonly-the-target-of-schemes-to-extend-patent-exclusivity/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: Origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316:858–871. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]