Abstract

Purpose:

Navigation of a complex and ever-changing health care system can be stressful and detrimental to psychosocial well-being for patients with serious illness. This study explored women’s experiences with navigating the health care system during treatment for ovarian cancer.

Methods:

Focus groups moderated by trained investigators were conducted with ovarian cancer survivors at an academic cancer center. Personal experiences with cancer treatment, provider relationships, barriers to care, and the health care system were explored. Sessions were audiotaped, transcribed, and coded by using grounded theory. Subsequently, one-on-one interviews were conducted to further evaluate common themes.

Results:

Sixteen ovarian cancer survivors with a median age of 59 years participated in the focus group study. Provider consistency, personal touch, and patient advocacy positively affected the care experience. Treatment with a known provider who was well acquainted with the individual’s medical history was deemed an invaluable aspect of care. Negative experiences that burdened patients, referred to as the “little big things,” included systems-based challenges, which were scheduling, wait times, pharmacy, transportation, parking, financial, insurance, and discharge. Consistency, a care team approach, effective communication, and efficient connection to resources were suggested as ways to improve patients’ experiences.

Conclusion:

Systems-based challenges were perceived as burdens to ovarian cancer survivors at our institution. The role of a consistent, accessible care team and efficient delivery of resources in the care of women with ovarian cancer should be explored further.

INTRODUCTION

As health care’s complexities increase, so do the challenges patients with cancer and their caregivers face as they attempt to navigate the system. These challenges are especially relevant for women with ovarian cancer, who may require a multidisciplinary team to execute a complex surgical and medical treatment plan. Feelings of social isolation, distress, depression, and anxiety are commonly reported by ovarian cancer survivors, and these emotions wax and wane during the course of illness and treatment.1-3 The profound physical and mental effects of ovarian cancer and its treatments can be exacerbated by the stress of navigating a complex plan of care, which can have a profound impact on psychosocial health; adherence; stress; quality of life; and in some cases, oncologic outcomes.4

Patient-reported outcomes are important factors in determining the quality and overall value of health care. Patient satisfaction survey results affect hospital rankings and reimbursements. Face-to-face physician interactions comprise only a small fraction of the patient’s experience. Significant efforts have been put into developing navigation systems, computer portal systems, and increased ancillary staff to assist patients with cancer as they proceed through treatment. However, evaluation of the impact of these interventions on patients’ experiences remains a challenge.5

This qualitative study explored women’s experiences with navigating the health care system as they underwent treatment for ovarian cancer at our institution. With a better understanding of the challenges these patients perceived, modifiable barriers to care, inefficiencies, and patient stressors may be identified and systems improved.

METHODS

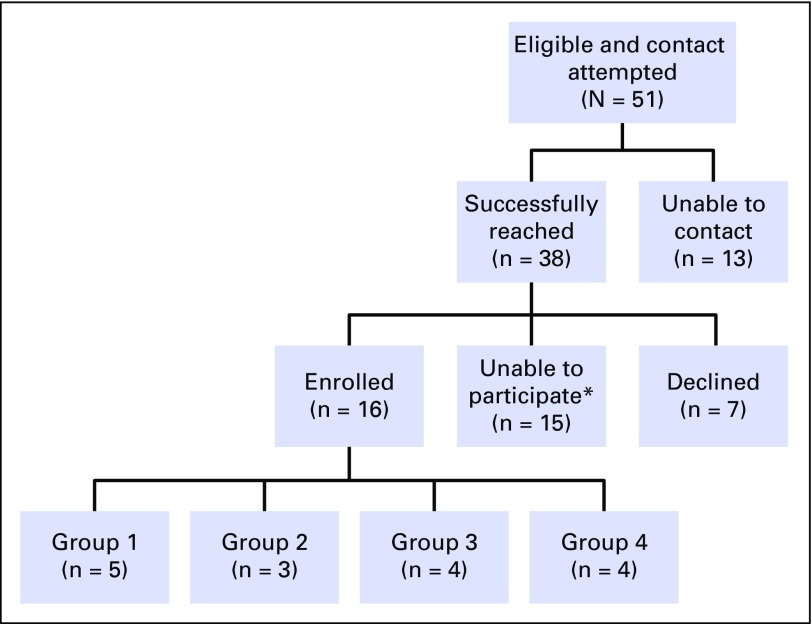

An institutional database was used to identify women older than 18 years of age treated for ovarian cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The study was approved by the institutional review board. Patient contact information and demographic data were collected. Clinical information on cancer stage, treatment, and outcomes was abstracted from the medical record. Women were excluded if < 9 months had transpired from treatment initiation, defined as initial surgery or chemotherapy cycle, to study start date. Study investigators contacted women by phone in reverse chronologic order and asked them to participate in a focus group to discuss their experiences with ovarian cancer treatment and the health care system (Fig 1). Follow-up phone calls (up to three) were made to nonresponders. A focus group session was coordinated once a sufficient number of women (defined as three or more) agreed to participate. Thus, participant were sequentially accrued. Written informed consent, including permission to audiotape, was obtained on the day of the focus group session. Focus groups comprised three to five women per session and lasted up to 2 h. The sessions were moderated by a trained facilitator who used a discussion guide with open-ended questions on possible social, communication, logistical, and financial barriers to ovarian cancer. All focus groups were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, coded, and analyzed by a qualitative research consultant.

FIG 1.

Participant recruitment flowchart. *Reasons for not participating: geographic (n = 8), in treatment (n = 2), other logistical conflict (n = 5).

Transcripts were analyzed through inductive thematic analysis to enable themes to emerge organically from the data. Transcripts were read repeatedly to obtain an overall sense of the discussion and to gauge significant themes. Transcripts were then coded with ATLAS.ti software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) in a two-step process: Line-by-line coding of all transcripts was first executed and then the generated codes were analyzed to create a codebook. This codebook was revised by the principal investigators to ensure that it captured the research aims and then used to recode of all transcripts.

Sample sizes for qualitative research studies generally are much smaller than that of quantitative studies. The purpose of qualitative research is to gain an in-depth understanding of individual experiences. Thus, data saturation is the guiding principle for sample size determination in qualitative research. A study has achieved data saturation if more data do not necessarily yield more information. Sample size is not determined a priori because the data collection phase continues until data saturation is achieved. Typically, three to five focus groups are needed for data saturation, although this number may vary on the basis of study topic and population.6,7

After completing the focus group phase, data saturation was determined to not have been met. Collaboration between the consultant and principal investigator yielded a set of research questions on the basis of both the research goals and the prominent themes from the data coding. Subsequent one-on-one follow-up interviews were conducted by phone. Interviews were conducted rather than additional focus groups due to feasibility and practicality. Sufficient overlap between themes from the initial and follow-up data indicated that all prominent themes were captured and that data saturation was achieved. Results of the qualitative analysis were then presented in themes framed by the research questions.6,7

RESULTS

Of the 51 living eligible women that were identified and called, 38 were successfully reached, and 16 women participated in four distinct focus group sessions (Fig 1). Seven follow-up interviews were conducted by phone. The median age at ovarian cancer diagnosis was 59 years (range, 27 to 71 years). Thirteen participants were white and three were African American. Participants’ insurance status was as follows: two public, nine private, and five private plus supplemental. Eleven were given a diagnosis of stage IIIC to IV disease. All participants underwent surgery, and 15 received chemotherapy. At the time of the focus groups, eight participants were still in their first clinical remission, and eight had active recurrent disease.

Barriers to Care and the “Little Big Things”

Participants emphasized situations outside the physician-patient encounter as the biggest obstacles. They almost unanimously agreed that treatment scheduling and wait time were among the most dominant issues encountered. They also identified financial, insurance, transportation, pharmacy, and discharge issues. Participants were frustrated by challenges with connecting to resources that could address their physical and psychologic adverse effects and complications. One participant verbalized how these elements negatively affected the care experience, especially during periods of physical and emotional exhaustion, as the “little big things.” There was overwhelming consensus among participants about the frustrating, time-consuming, and exhausting nature of having to self-advocate or navigate the system on one’s own. However, the participants emphasized that they intended to continue with the same provider despite negative logistical experiences. The participants conveyed that the institution’s reputation inspired trust and confidence as they underwent treatment.

So, care wise...I really am very grateful…systems wise [chuckles], that’s where I had my problem.

The big things seem to work okay. It’s...all these little things…and they’re not really little.

Consistency and the Human Element

Provider attitudes shaped the way participants perceived the quality of their care. Providers with a personal touch, those who made patients feel like they were the only patient or like they were being treated as special were lauded. Participants also spoke positively about experiences where they perceived that their providers advocated for them to access a needed resource or to connect them to another provider. Positive provider relationships were described as intimate, attentive, and collaborative, which were reported to inspire trust, comfort, optimism, and hope. The types of dissatisfaction participants expressed about providers were related to provider turnover, incomplete transmission of information to patients, difficulty with contacting physicians directly when in need of assistance, and confusion about which provider to contact. These issues increased the participants’ beliefs that they were left on their own to access the care and resources they needed. When seeking assistance over the phone or after hours, participants stated that they were rarely connected to a provider well versed in their condition. They believed that this diminished the quality of care they received and in certain instances, provoked their distrust of providers. Furthermore, if the interaction required one to repeat her medical history from the beginning, participants found this emotionally taxing and time consuming.

Another issue participants discussed was that information relevant and helpful to them did not always reach them, for example, information about a patient’s case that the physician failed to communicate. This issue also encompassed the failure to inform patients about available resources that could improve their treatment experience. During the focus groups, not all participant expressed an awareness of available resources, and some expressed that they found out about resources “after the fact.”

Participants often referenced family members and friends who helped to support and advocate for them and to coordinate their care. They expressed gratitude that this resource was available in situations where they could not have helped themselves or would have been forced to self-advocate in a time of physical and emotional exhaustion.

I just feel like there needs to be somebody who manages, who helps you manage all the administrative pieces, all...those kinds of things...that you can depend on to get the right information.

I found communications were very confusing at first. Who to talk to, you know, to call anytime. You know, “this is the number,” and then you might phone that number, you might make it a callback, and then you might get someone you don’t recognize.

Timing

Timing was a key positive and negative component of the participants’ experience with care. They appreciated when the timing of a procedure or appointment was perceived as meeting their sense of urgency. Participants reported negative experiences when the course of treatment or the provider who performed the procedure was changed unexpectedly or when the appointment or procedure occurred later than when the patient perceived it was needed. Despite their understanding that every patient’s cancer and, therefore, treatment process are slightly different, participants believed that some way should exist to better prepare patients for the steps of their treatment so that they can be better prepared psychologically.

Making Change

The aforementioned issues were not blamed on the physicians themselves but on a system that requires physicians to act outside their specialty or that spreads them too thin. Participants frequently explained that despite their knowledge that a particular need or grievance did not fall directly within the physician’s scope of responsibilities, they sought them out as a resource because of the lack of a scaffolding of other providers and resources that could address their needs throughout the treatment process.

Human contact was important to patients when they encountered psychological and physiologic adverse effects or logistical uncertainties. To address needs that were related to cancer but outside medical treatment, participants repeatedly suggested that a care team be implemented. They proposed that this team comprise nurses; financial and insurance personnel; social workers; and other personnel familiar with physical, psychological, and logistical resources who together would treat the whole person. The team should include a consistent set of providers well versed in the patient’s case who would advocate for the patient and coordinate the various components of care. The participants believed that this team would diminish the tiring and repetitious process of having to re-explain medical history, symptoms, or specific needs and to reduce the need for the patient to find appropriate resources and fight to be connected with them. This support was deemed particularly paramount because of the physical and emotional toll of cancer, which was perceived as making self-advocating or navigating the system alone particularly burdensome.

In addition to proposing that a knowledgeable team of health care providers be consistently available to patients, participants also suggested that information be compiled in written form. They believed that written information about adverse effects or resources for physical or logistical issues would reduce some of the patient reliance on providers. This would also reduce the time patients spend on researching resources on their own and would reduce the fear and uncertainty they experience throughout their treatment. In addition, participants suggested that ovarian cancer providers have a centralized list of resources with phone numbers that would allow patients to access resources for general issues related to ovarian cancer but not specific to surgery or chemotherapy. In this way, trusted ovarian cancer providers would act as a conduit to providers or resources needed for complications or adverse effects outside those of surgery.

They should give you an idea on paper who is your exact team, who you contact for different things.

[Having a care team] also allows when you do go and see the doctor, to focus on the things that need to be focused on.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this qualitative study was to explore and describe the unique experiences of women with ovarian cancer at our institution as they interact with the health care system during their treatment, with specific attention paid to perceived barriers to care and recommendations for improvements. The findings highlight aspects of a patient’s interaction with a specific institutional health care system, both those perceived as stressful and difficult and those perceived as comforting.

Communication between patients and the health care system was a prominent theme encountered throughout the focus group sessions. In a qualitative study by Frey et al8 that addressed the goals of care of ovarian cancer survivors, communication between patient and provider was consistently reported as an essential aspect of a patient’s experience. The current study findings emphasize and expand on this concept by identifying the importance of communication beyond that of the physician-patient relationship; communication must occur on multiple levels throughout the patient’s health care experience.

Previous studies have shown that patients with cancer believe that their psychosocial support needs often are unmet.9,10 Participants in the current study consistently voiced frustrations about obtaining access to institutional support resources. These findings are consistent with previous reports that a substantial number of ovarian cancer survivors experience difficulty with accessing psychosocial support resources.11 Although many patients prefer to discuss psychosocial issues with their attending physician,12 this may be insufficient. A study by Fagerlind et al13 about oncologists’ perceptions of barriers to psychosocial communication shed light on the challenges providers face as they attempt to meet patients’ psychosocial needs. Clinical providers reported insufficient consultation time, lack of methods to evaluate psychosocial needs, and lack of resources to handle reported psychosocial issues were found to be among the most common barriers. From both a patient and a provider perspective, a team approach is required to address the psychosocial needs of patients with cancer. Participants in the current study suggested the concept of a multidisciplinary care team to improve consistency of care and accessibility to providers.

Participants discussed the impact of the so-called little big things and the collective burden that a lack of care coordination had on them and their families. Patient navigation, defined as individualized and personal assistance to patients and caregivers to overcome barriers and facilitate access to multidisciplinary care, has been previously suggested as a solution to many of the challenges the participants identified.14-16 The Commission on Cancer, a program of the American College of Surgeons, has included a patient navigation process as part of its 2012 standards that starts at the time of screening and continues through diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.17 The patient navigation process, however, is not formally delineated. Institutions are advised to design their own process and to audit it regularly on the basis of community needs assessments to identify barriers to care and disparities. Although the current study focused on patient experiences during active treatment, the challenges of navigating a complex health care system extend to survivorship. Continued support, including the use of survivorship plans, has been proposed as a possible intervention to assist patients beyond active treatment.

Patient navigation has previously been shown to improve cancer-related health outcomes18,19 as well as to improve satisfaction and decrease concerns and anxiety.20,21 Participants in the current study overwhelmingly reported confusion about whom to call and when at our institution. In an ideal system, each patient would be connected with their own patient navigator who is well versed in both patient needs and the medical environment. If resources are limited, care team maps, or specific written instructions that delineate the resources within the system, can be used as an initial step. The study participants also suggested that clearly written information on the care team, complete with contact information and explicit instructions on whom to call and when, would be of great benefit and comfort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Care Team Map

The qualitative design of this study is well suited to explore the patient experience in a complex, ever-changing health care environment. By gaining a deeper understanding of patients’ lived experiences, hypotheses can be generated and interventions developed for direct application to cancer care delivery models. Addressing these challenges within the patient-system relationship may lead to improved patient satisfaction, which has become an important determinant of health care quality and has affected reimbursements. This study focused on patients with ovarian cancer, who represent a population with a long-term and multifaceted relationship with the health care system; however, the issues explored may be relevant to many other patients with a variety of medical needs. Although the solutions seem to be common sense, these systems-based burdens on patients commonly are overlooked; therefore, this study contributes to our understanding of what patients experience during their cancer care.

A potential limitation of this study design was the composition of the focus groups. Such smaller or mini–focus groups could potentially narrow the range of patient experiences explored, but when the topics of interest are highly personal and require a greater depth of discussion, smaller groups allow for greater space and time for participants to share. Because of the single-institution setting and small, relatively homogenous sample, the experiences described may not be generalizable to all settings; however, data saturation was reached, which suggests the validity of the findings within a representative academic institution. Vulnerable populations, such as the uninsured or underinsured, which may be over-represented in the women we were unable to contact, comprised only a small part of our study population. These women inevitably face even greater challenges and should be the focus of future studies.

Overall, the results of this study highlight the perceived systems-related challenges and burdens that ovarian cancer survivors face as they navigate the complex health care environment of our institution. In addition to using patient navigators during ovarian cancer care, further work is needed to assess the potential benefit of a consistent and accessible patient care team.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A.I.T. is the recipient of a fellowship (NCI R25 CA094061-11) from the National Cancer Institute.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Adil H. Haider, Janice V. Bowie, Ana I. Tergas

Collection and assembly of data: Kara Long Roche, Ana M. Angarita, Melissa Lippitt, Amanda N. Fader, Ana I. Tergas

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

“Little Big Things”: A Qualitative Study of Ovarian Cancer Survivors and Their Experiences With the Health Care System

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jop.ascopubs.org/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Kara Long Roche

No relationship to disclose

Ana M. Angarita

No relationship to disclose

Angelica Cristello

Employment: Royal DSM

Consulting or Advisory Role: Happy Vitals

Melissa Lippitt

No relationship to disclose

Adil H. Haider

Stock or Other Ownership: cofounder and equity shareholder of Patient Doctor Technologies, the company that runs the Web site www.doctella.com

Janice V. Bowie

No relationship to disclose

Amanda N. Fader

Honoraria: Genentech

Ana I. Tergas

Consulting or Advisory Role: Helomics

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferrell B, Smith SL, Cullinane CA, et al. Psychological well being and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Cancer. 2003;98:1061–1071. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodurka-Bevers D, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, et al. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:302–308. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton TR, Manne SL, Rubin S, et al. Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: The role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychol. 2005;24:143–152. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roland KB, Rodriguez JL, Patterson JR, et al. A literature review of the social and psychological needs of ovarian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2408–2418. doi: 10.1002/pon.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26269. Guadagnolo BA, Dohan D, Raich P: Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment: Crafting a policy-relevant research agenda for patient navigation in cancer care. Cancer 117:3565-3574, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruff CC, Alexander IM, McKie C. The use of focus group methodology in health disparities research. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311:299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frey MK, Philips SR, Jeffries J, et al. A qualitative study of ovarian cancer survivors’ perceptions of endpoints and goals of care. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, et al. Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: A prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6172–6179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrell BR, Smith SL, Juarez G, et al. Meaning of illness and spirituality in ovarian cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:249–257. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Söllner W, Zingg-Schir M, Rumpold G, et al. Need for supportive counselling—the professionals’ versus the patients’ perspective. A survey in a representative sample of 236 melanoma patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67:94–104. doi: 10.1159/000012266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagerlind H, Kettis Å, Glimelius B, et al. Barriers against psychosocial communication: Oncologists’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3815–3822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Percac-Lima S, Grant RW, Green AR, et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: A randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:211–217. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J, et al. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82:216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American College of Surgeons: Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care, V1.2.1. Chicago, IL, American College of Surgeons, 2012.

- 18.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science. Cancer. 2008;113:1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113:3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: A randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85:114–124. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillion L, de Serres M, Cook S, et al. Professional patient navigation in head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]