Abstract

Purpose

Alterations in DNA damage response and repair (DDR) genes are associated with increased mutation load and improved clinical outcomes in platinum-treated metastatic urothelial carcinoma. We examined the relationship between DDR alterations and response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

Methods

Detailed demographic, treatment response, and long-term outcome data were collected on patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with atezolizumab or nivolumab who had targeted exon sequencing performed on pre-immunotherapy tumor specimens. Presence of DDR alterations was correlated with best objective response per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and progression-free and overall survival.

Results

Sixty patients with urothelial cancer enrolled in prospective trials of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies met inclusion criteria. Any DDR and known or likely deleterious DDR mutations were identified in 28 (47%) and 15 (25%) patients, respectively. The presence of any DDR alteration was associated with a higher response rate (67.9% v 18.8%; P < .001). A higher response rate was observed in patients whose tumors harbored known or likely deleterious DDR alterations (80%) compared with DDR alterations of unknown significance (54%) and in those whose tumors were wild-type for DDR genes (19%; P < .001). The correlation remained significant in multivariable analysis that included presence of visceral metastases. DDR alterations also were associated with longer progression-free and overall survival.

Conclusion

DDR alterations are independently associated with response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. These observations warrant additional study, including prospective validation and exploration of the interaction between tumor DDR alteration and other tumor/host biomarkers of immunotherapy response.

INTRODUCTION

The recent approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors that target the PD-1/PD-L1 axis (atezolizumab,1 nivolumab,2,3 durvalumab,4 avelumab,5 and pembrolizumab6) has revolutionized the management of metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC). Although response rates are relatively low (15% to 24%), responders can experience durable disease control compared with prior systemic agents. The identification of clinically useful biomarkers that identify patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) remains an ongoing challenge. PD-L1 expression assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is not a robust predictive biomarker of response to ICB in mUC. Features of the host (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, T-cell receptor clonality) and tumor (molecular subtypes, mutation load [ML]) currently are being evaluated as predictive biomarkers for ICB in multiple cancer types.7-10 Higher ML has been associated with an increased objective response rate (ORR) in patients with urothelial cancer treated with atezolizumab,7,9 although high ML does not guarantee response, and low ML does not preclude response.

Urothelial carcinoma displays a complex genomic landscape,11 including defective DNA damage response and repair (DDR) at the somatic genomic level.12-15 Alterations in DDR genes are associated with an elevated ML,13,16 increased tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes,17 and enhanced platinum responsiveness, which lead to a higher likelihood of pathologic downstaging in neoadjuvantly treated bladder cancers12,14,18,19 and improved survival outcomes in the metastatic setting.13 On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that the presence of DDR gene mutations is associated with clinical benefit from anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with mUC.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

After institutional review board approval, we identified patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of mUC enrolled in prospective clinical trials of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02553642, NCT01928394, and NCT02108652) with identical eligibility criteria. Two of these studies have been reported previously.1,2 Informed consent was obtained before tumor sequencing as part of a genomic profiling protocol.

The primary objective of this analysis was to examine the effect of DDR gene alterations on ORR. The secondary objective was to assess correlations between DDR alterations and both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Two separate analyses of DDR alterations were performed: any DDR alterations and known or likely deleterious DDR alterations defined as hot spot point mutations or loss-of-function alterations in tumor suppressor genes.

Data Collection

Baseline clinical characteristics were extracted, including sex, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), hemoglobin, sites of metastatic disease at the start of anti-PD-1/PD-L1, time since last platinum-based therapy, prior systemic therapies for metastatic disease, and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agent received. The primary outcome of interest was ORR, defined as the proportion of patients who achieved a radiographically confirmed complete or partial response as their best response to anti-PD-1/PD-L by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1.

The Bellmunt risk factors (ECOG PS > 0, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, and liver metastases) were used to define subgroups on the basis of the presence of zero to three prognostic factors.20 Visceral metastasis was defined as liver, lung, bone, or non-nodal soft tissue metastasis.

Tumor Sequencing

Tumor sequencing was performed using the Memorial Sloan Kettering Integrated Molecular Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) clinical sequencing assay.21,22 MSK-IMPACT is a hybridization capture–based next-generation sequencing platform that is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved and performed in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory. Patients were analyzed using one of three versions of the assay, each of which examines all exons and selected introns within 341; 410; and most recently, 468 genes. Beginning in April 2016, a companion protocol was offered to patients at physician discretion to analyze further selected germline regions to identify potentially heritable pathogenic germline variants associated with cancer predisposition syndromes.23

DDR Genes and Determination of Deleterious Mutation Status

Thirty-four genes within the MSK-IMPACT panel were previously identified as DDR related13 according to PubMed searches and the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene and BioSystems Databases (Data Supplement). All 34 genes were covered in all three versions of MSK-IMPACT.

All loss-of-function alterations were considered deleterious, including deletions, nonsense mutations, and frameshift or splice site alterations. For missense mutations, deleterious status was determined by manual review for their documentation in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer,24 algorithmically determined recurrent hot spot mutations,25,26 and annotation of oncogenicity by OncoKB.27, 28 On the basis of previous work, all ERCC2 missense mutations within or near conserved helicase domains were considered deleterious.14

Determination of ML

ML was determined by the number of nonsynonymous protein-coding mutations identified by MSK-IMPACT divided by the total sequenced genome length in megabases. Copy number gene alterations and structural rearrangements were excluded. The number of mutations detected through MSK-IMPACT was previously shown to correlate with total ML in the urothelial The Cancer Genome Atlas data set13 and on whole-exome sequencing.22

Statistical Methods

Patients were divided into subgroups on the basis of DDR alteration status: deleterious DDR alterations, DDR alterations of unknown significance, and wild-type DDR genes. Baseline characteristics were compared by using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Response data were prospectively assessed by using RECIST version 1.1 during the conduct of the respective clinical trials and retrieved for this study. Logistic regression was used to test for associations between factors of interest and objective response, with results presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% Wald CIs.

OS was calculated from protocol registration date until the date of death or last follow-up. Patients still alive at last follow-up were censored for OS. PFS was calculated from the registration date to the date of progression, death, or last follow-up. Patients alive and without progression were censored for PFS. Both PFS and OS were estimated by Cox proportional hazards regression and graphically by Kaplan-Meier method. Comparisons of PFS and OS between groups were performed by using the log-rank test.

For multivariable analyses, variables or parameters that achieved a level of significance ≤ .05 were entered into multivariable models and removed if they were no longer significant at α = .05 in the presence of other variables. Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to compare multivariable logistic regression models for objective response. AIC assesses relative goodness of fit between models. Lower values of AIC indicate a better fit and predictive value. All tests were two-sided, and P < .05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Cohort

Seventy-eight patients with mUC were enrolled in three separate prospective anti-PD-1/PD-L1 studies between April 2014 and December 2016. Eighteen patients were excluded: 10 in whom MSK-IMPACT was not performed, seven in whom there was inadequate tissue or DNA for sequencing, and one in whom sequencing was performed on tumor tissue obtained after PD-1/PD-L1 treatment. Sixty patients, therefore, were available for analysis (Fig 1). The median age of the cohort was 67 years (range, 32 to 84 years), and the majority of patients were male (88.3%). Fifteen patients (25.0%) had an ECOG PS of 0, and the rest had an ECOG PS of 1. Most patients (76.7%) had visceral metastases. Five patients were treated with first-line anti-PD-1/PD-L1, and 17 were treated after progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Median time from the end of platinum-based chemotherapy to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 was 9.2 months (range, 0.3 to 150.0 months). Most patients (71.7%) received the anti-PD-1 nivolumab, whereas the rest were treated with the anti-PD-L1 atezolizumab (Table 1).

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of the study. CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; MSK-IMPACT, Memorial Sloan Kettering Integrated Molecular Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

DDR Gene Alteration Status

All sequenced tumors were obtained before the start of anti-PD-1/PD-L1, with a median time of 9.6 months (range, 0.1 to 104.6 months) from specimen acquisition to the start of treatment. Twenty-five patients (41.7%) also underwent analysis of germline sequences, with reporting of known and likely pathogenic germline variants in the electronic medical record.

Overall, 74 DDR gene alterations were observed in 28 patients (46.7%), with a median of one DDR alteration per patient (range, one to 34; Data Supplement). Twenty-seven deleterious DDR gene alterations were observed in 15 patients (25.0%). The most commonly altered genes were ATM (n = 7); POLE (n = 3); and BRCA2, ERCC2, FANCA, and MSH6 (n = 2 each; Data Supplement). Two patients harbored pathogenic germline DDR gene alterations (one with MSH2 and the other with both CHEK2 and BRCA1). For the patient with germline MSH2 alteration, copy neutral loss of heterozygosity was noted in the tumor. For the patient with CHEK2/BRCA1 alterations, no loss of heterozygosity was observed in the tumor. Both alterations (BRCA1 E23Vfs*17 and CHEK2 S428F) were previously shown to be deleterious.29,30

We also examined the distribution of the 27 deleterious DDR alterations by pathways or mechanisms. Genes involved in double-strand break detection (n = 8) or repair (n = 7), mismatch repair (MMR; n = 5), and nucleotide excision repair (n = 3; Data Supplement) were the most commonly involved. In summary, 16.7% of patients (10 of 60) harbored deleterious alterations in genes that involved the double-strand break detection/repair mechanisms and 5.0% (three of 60) in MMR pathways, one of which harbored three deleterious MMR gene alterations.

Association Between DDR Status and Observed Clinical Phenotypes

In a comparison of clinical characteristics among patients with deleterious DDR alterations, non-deleterious DDR alterations, and no DDR alterations, those with deleterious DDR alterations had better ECOG PS (0 v 1: 60.0% v 0.0% v 18.8%; P < .001) and lower incidence of hepatic involvement (0.0% v 30.8% v 37.5%; P = .011; Table 1). Consistent with prior observations, deleterious DDR alterations were associated with higher ML (P < .001; Data Supplement).

Association Between DDR Status and Response to ICB

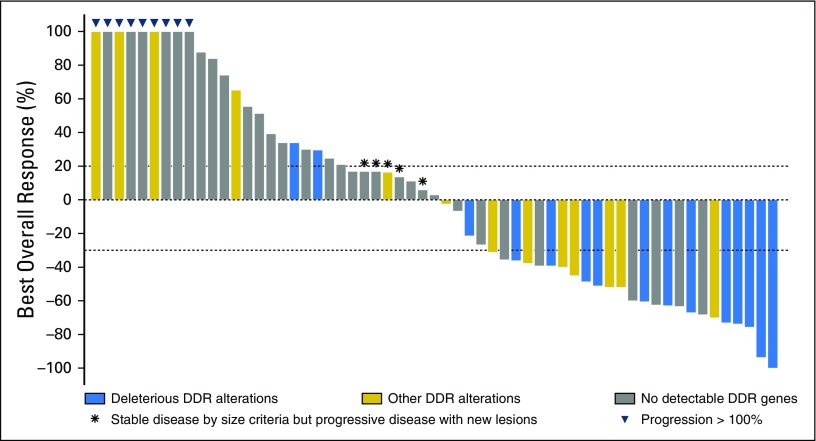

Best objective responses for all patients are depicted in Fig 2. Objective responses were observed in 25 patients during anti-PD-1/PD-L1, which corresponds to an ORR of 41.7%. The presence of DDR alterations was associated with a higher ORR than those without any DDR alterations (67.9% v 18.8%; P < .001). The finding of a known/likely deleterious DDR alteration was associated with an ORR of 80% versus 53.9% for patients with DDR alterations of unknown significance and 18.8% for those without DDR alterations (P < .001).

Fig 2.

Waterfall plot of observed best responses from anti-PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. DDR, DNA damage response and repair.

In univariable logistic regression analysis, the presence of visceral metastasis was inversely associated with ORR, whereas DDR status and ML were associated with responses from immune checkpoint inhibitors (Table 2). As a result of collinearity between DDR alteration status and ML, the latter was not entered into the final multivariable model. In this model, DDR status and visceral metastases remained independent predictors of ORR. Compared with those without DDR alterations, deleterious DDR alterations were associated with an OR of 19.02 for objective response (P < .001), whereas DDR alterations of unknown significance were associated with an OR of 5.79 (P = .024; Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of Objective Response

In alternative multivariable models where ML was included in place of DDR status, ML and visceral metastases were independent predictors for responses, with an AIC value of 70.25 versus 66.09 for the model with DDR alteration status. This finding suggests that models that incorporate DDR alterations provide more information than those that use ML. DDR status also was an independent predictor for objective response when controlled for ML (Data Supplement).

Survival Outcomes and the Effect of DDR Alteration Status

With a median follow-up of 19.6 months, 40 events were recorded, and 34 patients died. Median PFS and OS for the entire cohort were 4.5 and 15.8 months, respectively (Data Supplement).

For patients with deleterious DDR alterations, median PFS was not reached, and the 12-month PFS rate was 56.6%. Median PFS for those with DDR alterations of unknown significance and for those without DDR gene alterations was 15.7 and 2.9 months, respectively (Fig 3A). In univariable analysis, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, ML, and DDR alteration status were significantly associated with PFS. In a multivariable model, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL remained an independent poor prognostic indicator for PFS. Deleterious DDR alterations were significantly associated with improvement in PFS compared with patients without detectable alterations (hazard ratio [HR], 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.50; P < .001), whereas DDR alterations of unknown significance showed borderline improvement in PFS (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.19 to 1.04; P = .062; Table 3).

Fig 3.

(A) Progression-free survival by DNA damage response and repair (DDR) alteration status. (B) Overall survival by DDR alteration status. delDDRmt, deleterious DDR alterations; DDRmt, nondeleterious DDR alterations; DDRwt, nondetectable DDR gene alterations; NR, not reached.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of Progression-Free Survival

The median OS was not reached for patients with deleterious DDR alterations, with 71.5% alive at 12 months, whereas the median OS for those with DDR alterations of unknown significance or no detectable DDR alterations were 23.0 and 9.3 months, respectively (Fig 3B). In a univariable analysis, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, visceral metastases, and DDR status were associated with OS. In multivariable analysis, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL and visceral metastases remained independent prognostic indicators for poorer OS. Deleterious DDR alterations conferred superior OS compared with no detectable DDR gene alterations (HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10 to 0.73; P = .001). Patients with DDR alterations of unknown significance showed borderline improvement in OS compared with unaltered DDR genes (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.18 to 1.19; P = .109), which suggests that some of the alterations of unknown significance may be functional variants (Table 4). Additional multivariable analyses for PFS and OS with ML in place of DDR status, stratification by DDR status, and stratification by ML showed that DDR-containing models remained a superior predictor of outcomes compared with ML (Data Supplement; Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of Overall Survival

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that alterations in a panel of DDR genes were strongly associated with clinical benefit among patients with mUC treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1. DDR genes are frequently altered in urothelial cancers and were observed in 46.7% of tumors in the study cohort of which 25.0% were considered deleterious. Association with clinical outcomes was more pronounced in tumors with deleterious DDR alterations than in those with variants of unknown significance in DDR-associated genes. Conversely, the association was not observed with non-DDR genes (Data Supplement).

This study represents one of the first reports to examine the association between ICB response and defective DDR mechanisms beyond MMR deficiency. In MMR-deficient tumors, pembrolizumab was associated with an ORR of 50% among 12 cancer types studied (none of which were mUC), which led to FDA approval of pembrolizumab regardless of primary tumor site.31-33 However, deleterious alterations in MMR pathway occurred in 5% of the current study cohort (18.5% of all deleterious DDR alterations). In mUC, genes involved in double-strand break detection and repair mechanisms were most frequently altered, which represent two thirds of the observed deleterious DDR alterations. These tumors derived clinical benefit from ICB, which is consistent with observations from a series of 38 patients with metastatic melanoma where responders to anti-PD-1 were enriched for BRCA2 mutations (28% v 6%).34 However, whether DDR alterations beyond MMR deficiency represent a disease-agnostic phenomenon remains unknown.

To date, no validated predictive biomarkers of response to anti-PD1/PD-L1 exist in mUC. Although these agents function by interrupting PD-1/PD-L1 signaling, which increases cytotoxic T-cell–mediated antitumor responses,10,35 tumor or immune cell PD-L1 expression in mUC by IHC does not have a clearly reproducible relationship to treatment response. Despite FDA approval of two PD-L1 IHC companion diagnostics, multiple PD-L1 IHC assays have demonstrated conflicting data in mUC, and their clinical utility remains unproven.2-6,9

ML was previously shown to be associated with clinical benefit in mUC.7,9 However, ML is a continuous variable without a clearly defined cut point below which responses do not occur and above which response is guaranteed. In contrast, DDR mutations are easily detected with next-generation sequencing assays, and their presence in the current data set was strongly associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 response. In this cohort, DDR status was superior to ML at predicting responses, PFS, and OS in various multivariable models and remained significant when controlling for ML. However, because of the observed collinearity of DDR alterations and ML, mutual independence among these features could not be demonstrated.

Other non-neoantigen– and/or ML-based mechanisms have been postulated to account for the additional influence of DDR alterations on ICB treatment outcome.36 For example, the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway was initially described as a host response to viral infection and potential etiology for autoimmune diseases.37 The STING pathway induces innate host response in preclinical cancer models38-40 and is activated upon contact with cytosolic DNA fragments, which culminate in a type 1 interferon response. Accumulation of cytosolic DNA fragments that arise from defective DDR mechanisms provides triggers to prime the STING pathway for activation.41,42 In a PD-1/PD-L1 blockade-resistant mouse model, exposure to synthetic DNA fragments leads to STING-dependent antitumor activity in combination with anti-PD-1, which further supports this hypothesis43 but awaits confirmation and replication in a clinical setting.

Contrary to previous reports, hepatic metastasis was not associated with poorer outcomes in the current study likely because of sample size. We did observe an association between deleterious DDR status and an absence of hepatic metastasis, which supports our previous observation in platinum-treated mUCs (wild-type DDR, 20.0%; more than one DDR alteration, 0.0% to 7.7%)13 and suggests a biologic basis worthy of additional investigation.

This retrospective analysis of prospectively treated patients has several limitations. First, the patients had better prognostic features and extended follow-up, which likely accounts for the higher ORR observed (Data Supplement). Second, the MSK-IMPACT assay does not include all known DDR genes; thus, additional low-frequency DDR genes might also contribute to improved clinical outcomes. Moreover, many missense mutations may have little or no effect on protein function; this is likely the basis for the weaker correlation between clinical outcomes and identified DDR alterations of unknown significance. Functional defects in individual genes, pathways, or mechanisms of DDR also are not likely to have an equal effect on DDR capability, and a larger cohort size is needed to determine whether the predictive value of mutations in individual DDR genes vary. Finally, this single-center study and our cohort were identified on the basis of sequential patients who underwent tumor sequencing with MSK-IMPACT rather than all patients enrolled in anti-PD-1/PD-L1 clinical trials, which might yield selection bias.

In conclusion, this study shows that patients with DDR gene alterations are more likely to experience objective responses, longer PFS, and improved OS than patients with wild-type DDR genes. Whether the association is predictive or prognostic should be investigated further in larger data sets from randomized studies that have led to the FDA approval of several anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents. In addition, we plan to validate these findings prospectively in an upcoming randomized phase II study of atezolizumab or atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in mUC. Additional investigation is warranted to evaluate the mechanisms that link DDR alterations (beyond MMR), ML and neoantigen load, and immunotherapy response. If validated in other studies, DDR alterations may represent a useful predictive biomarker of response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 in urothelial carcinoma.

Footnotes

Supported by Roche, Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant P30 CA008748.

Presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 2-6, 2017.

Clinical trial information: NCT02553642, NCT01928394, and NCT02108652.

See accompanying article on page 1710

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Min Yuen Teo, Margaret K. Callahan, Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Financial support: David B. Solit, Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Administrative support: Ashley M. Regazzi, David B. Solit, Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Provision of study materials or patients: Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Collection and assembly of data: Min Yuen Teo, Ashley M. Regazzi, Brooke E. Kania, Meredith M. Moran, Catharine K. Cipolla, Mark J. Bluth, Joshua Chaim, Maria I. Carlo, Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Data analysis and interpretation: Min Yuen Teo, Kenneth Seier, Irina Ostrovnaya, Joshua Chaim, Hikmat Al-Ahmadie, Alexandra Snyder, Maria I. Carlo, David B. Solit, Michael F. Berger, Samuel Funt, Jedd D. Wolchok, Gopa Iyer, Dean F. Bajorin, Margaret K. Callahan, Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Alterations in DNA Damage Response and Repair Genes as Potential Marker of Clinical Benefit From PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Advanced Urothelial Cancers

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Min Yuen Teo

No relationship to disclose

Kenneth Seier

No relationship to disclose

Irina Ostrovnaya

No relationship to disclose

Ashley M. Regazzi

No relationship to disclose

Brooke E. Kania

No relationship to disclose

Meredith M. Moran

No relationship to disclose

Catharine K. Cipolla

No relationship to disclose

Mark J. Bluth

No relationship to disclose

Joshua Chaim

No relationship to disclose

Hikmat Al-Ahmadie

Consulting or Advisory Role: EMD Serono, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Alexandra Snyder

Employment: Adaptive Biotechnologies

Stock or Other Ownership: Adaptive Biotechnologies

Honoraria: Genentech

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech

Maria I. Carlo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer

David B. Solit

Honoraria: Loxo Oncology, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Loxo Oncology

Michael F. Berger

Research Funding: Illumina

Samuel Funt

Stock or Other Ownership: Kite Pharma, UroGen Pharma (I)

Research Funding: Genentech, AstraZeneca

Jedd D. Wolchok

Stock or Other Ownership: Potenza Therapeutics, Tizona Therapeutics, Serametrix, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Trieza Therapeutics, BeiGene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, MedImmune, Polynoma, Polaris Group, Genentech, F-star, BeiGene, Sellas, Eli Lilly, Potenza Therapeutics, Tizona Therapeutics, Amgen, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Adaptive Technologies, Ascentage Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Merck, Genentech, Roche, MedImmune

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Co-inventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for treatment of cancer in companion animals, co-inventor on a patent for use of oncolytic Newcastle disease virus

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Amgen

Gopa Iyer

No relationship to disclose

Dean F. Bajorin

Honoraria: Merck Sharp & Dohme, Genentech, Roche

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche, Genentech, Merck, Eli Lilly, Fidia Farmaceutici, Eisai, UroGen Pharma

Research Funding: Dendreon (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Genentech, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly

Margaret K. Callahan

Employment: Bristol-Myers Squibb (I), Celgene (I), Kleo Pharmaceuticals (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Other Relationship: Clinical Care Options, Potomac Center for Medical Education

Jonathan E. Rosenberg

Stock or Other Ownership: Merck, Illumina

Honoraria: UpToDate, AstraZeneca, Medscape, Vindico Medical Education, PeerView

Consulting or Advisory Role: OncoGenex Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Merck, Agensys, Roche, Genentech, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Seattle Genetics, Bayer AG, Inovio Biomedical

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), OncoGenex Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Mirati Therapeutics (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Viralytics (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: ERCC2 predicting cisplatin sensitivity

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. : Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 387:1909-1920, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma P, Callahan MK, Bono P, et al. : Nivolumab monotherapy in recurrent metastatic urothelial carcinoma (CheckMate 032): A multicentre, open-label, two-stage, multi-arm, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol 17:1590-1598, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P, Retz M, Siefker-Radtke A, et al. : Nivolumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum therapy (CheckMate 275): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:312-322, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Powles T, O’Donnell PH, Massard C, et al: Updated efficacy and tolerability of durvalumab in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 (suppl; abstr 286) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apolo AB, Infante JR, Balmanoukian A, et al. : Avelumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in patients with refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma: Results from a multicenter, phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol 35:2117-2124, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. : Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 376:1015-1026, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. : Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 389:67-76, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. : Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348:124-128, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosenberg JE, Petrylak DP, Van Der Heijden MS, et al: PD-L1 expression, Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) subtype, and mutational load as independent predictors of response to atezolizumab (atezo) in metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC; IMvigor210). J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr 104) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder A, Nathanson T, Funt SA, et al. : Contribution of systemic and somatic factors to clinical response and resistance to PD-L1 blockade in urothelial cancer: An exploratory multi-omic analysis. PLoS Med 14:e1002309, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network : Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 507:315-322, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iyer G, Balar AV, Milowsky MI, et al: Correlation of DNA damage response (DDR) gene alterations with response to neoadjuvant (neo) dose-dense gemcitabine and cisplatin (ddGC) in urothelial carcinoma (UC). J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr 5011) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teo MY, Bambury RM, Zabor EC, et al. : DNA damage response and repair gene alterations are associated with improved survival in patients with platinum-treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 23:3610-3618, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Allen EM, Mouw KW, Kim P, et al. : Somatic ERCC2 mutations correlate with cisplatin sensitivity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Discov 4:1140-1153, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yap KL, Kiyotani K, Tamura K, et al. : Whole-exome sequencing of muscle-invasive bladder cancer identifies recurrent mutations of UNC5C and prognostic importance of DNA repair gene mutations on survival. Clin Cancer Res 20:6605-6617, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galsky MD, Uzilov AV, McBride RB, et al: DNA damage response (DDR) gene mutations (mut), mut load, and sensitivity to chemotherapy plus immune checkpoint blockade in urothelial cancer (UC). J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 (suppl; abstr 300) [Google Scholar]

- 17. McBride RB, Patel VG, Collazo Lorduy A, et al: Prognostic significance of DNA damage repair (DDR) mutations in patients with urothelial carcinoma (UC) and associations with tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr 4538) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu D, Plimack ER, Hoffman-Censits J, et al. : Clinical validation of chemotherapy response biomarker ERCC2 in muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2:1094-1096, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plimack ER, Dunbrack RL, Brennan TA, et al. : Defects in DNA repair genes predict response to neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol 68:959-967, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, et al. : Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol 28:1850-1855, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. : Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn 17:251-264, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333. Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al: Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med, 23:703-713, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5208. Schrader KA, Cheng DT, Joseph V, et al: Germline variants in targeted tumor sequencing using matched normal DNA. JAMA Oncol 2:104-111, 2016 [Erratum: JAMA Oncol 2:279, 2016] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, et al. : COSMIC: Somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D777-D783, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang MT, Asthana S, Gao SP, et al. : Identifying recurrent mutations in cancer reveals widespread lineage diversity and mutational specificity. Nat Biotechnol 34:155-163, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center: Cancer Hotspots, 2017. http://cancerhotspots.org/#/home.

- 27.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, et al. : OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol 2017:1-16, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center: OncoKB: Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. http://oncokb.org.

- 29.Johnston JJ, Rubinstein WS, Facio FM, et al. : Secondary variants in individuals undergoing exome sequencing: Screening of 572 individuals identifies high-penetrance mutations in cancer-susceptibility genes. Am J Hum Genet 91:97-108, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaag A, Walsh T, Renbaum P, et al. : Functional and genomic approaches reveal an ancient CHEK2 allele associated with breast cancer in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Hum Mol Genet 14:555-563, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. : PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 372:2509-2520, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. : Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357:409-413, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Food and Drug Administration: FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication, 2017 https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm560040.htm.

- 34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.010. Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, et al: Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell 165:35-44, 2016 [Erratum: Cell 168:542, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. : PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515:568-571, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mouw KW, Goldberg MS, Konstantinopoulos PA, et al. : DNA damage and repair biomarkers of immunotherapy response. Cancer Discov 7:675-693, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn J, Barber GN: Self-DNA, STING-dependent signaling and the origins of autoinflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol 31:121-126, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li T, Cheng H, Yuan H, et al. : Antitumor activity of cGAMP via stimulation of cGAS-cGAMP-STING-IRF3 mediated innate immune response. Sci Rep 6:19049, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, et al. : STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor immunity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity 41:843-852, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Hu S, Chen X, et al. : cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:1637-1642, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Härtlova A, Erttmann SF, Raffi FA, et al. : DNA damage primes the type I interferon system via the cytosolic DNA sensor STING to promote anti-microbial innate immunity. Immunity 42:332-343, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parkes EE, Walker SM, Taggart LE, et al. : Activation of STING-dependent innate immune signaling by S-phase-specific DNA damage in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 109:109, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu J, Kanne DB, Leong M, et al. : STING agonist formulated cancer vaccines can cure established tumors resistant to PD-1 blockade. Sci Transl Med 7:283ra52, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]