Abstract

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common type of pain in America, and spinal instability is a primary cause. The facet capsular ligament (FCL) encloses the articulating joints of the spine and is of particular interest due to its high innervation – as instability ensues high stretch values likely are a cause of this pain. Therefore, this work investigated the facet capsular ligament’s (FCL) role in providing stability to the lumbar spine. A previously validated finite element model of the L4-L5 spinal motion segment was used to simulate pure moment bending in multiple planes. FCL failure was simulated and the following outcome measures were calculated: helical axes of motion, range of motion, bending stiffness, facet joint space, and FCL stretch. Range of motion (ROM) increased, bending stiffness decreased, and altered helical axis patterns were observed with the removal of the FCL. Additionally, a large increase in FCL stretch was measured with diminished FCL mechanical competency, providing support that the FCL plays an important role in spinal stability.

Keywords: finite element model, lumbar spine, facet joint, instability, coupled motion

1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a debilitating condition that imposes quality-of-life and financial burdens [1]. Eighty percent of adults experience LBP in their lifetime, making it the most common type of pain reported by American adults [2]. One known cause of LBP is spinal instability, defined clinically as loss of the spine’s ability to maintain its displaced patterns during physiologic loads [3]. There are several different types of spinal instability, including traumatic, neoplastic, and degenerative [4]. This work aims to identify how diminished facet capsular ligament (FCL) integrity affects lumbar spinal mechanics, which is a potential contributor to LBP.

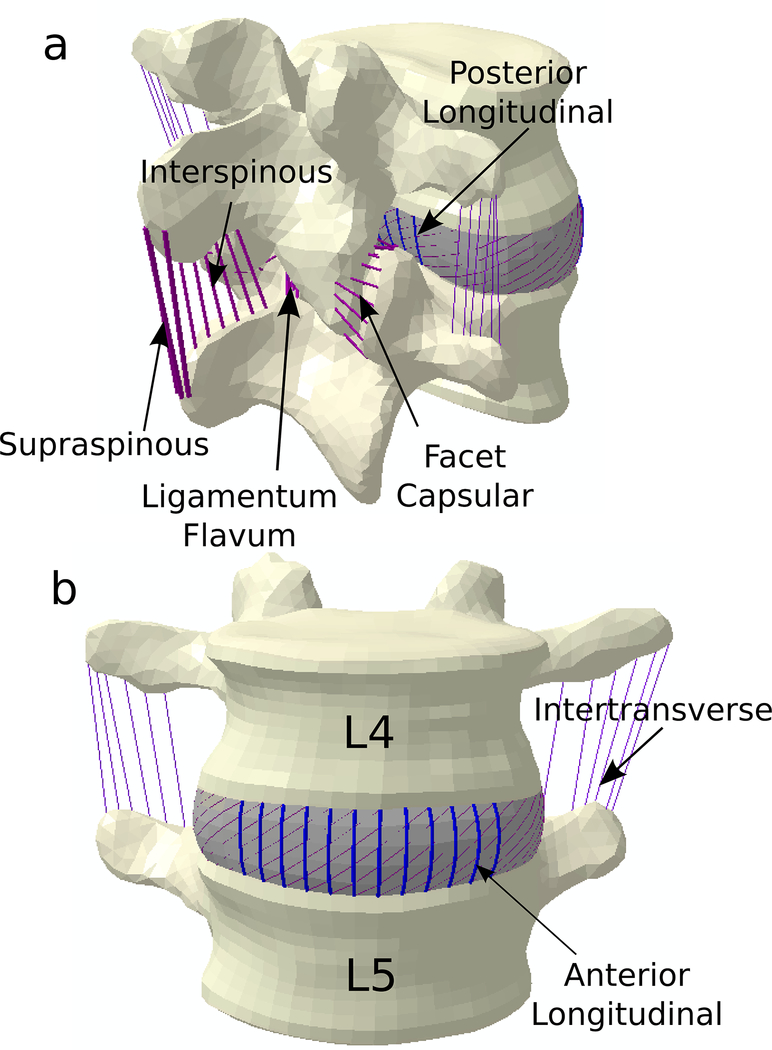

The facet joints flank the spinous processes on the posterior aspect of each vertebra along the length of the spine (Figure 1). The joint is composed of two facet surfaces from adjacent vertebrae and is encased by the ligamentum flavum and the FCL, constraining the synovial fluid and helping manage joint motion. The FCL is structurally complex and undergoes complex deformations during motion [5–7]. Nerve fibers embedded in the tissue generate proprioceptive and nociceptive signals, making the FCL a mechanosensory as well as structural tissue [8, 9]. Previous research on the stretch of the ligaments in the spine shows the FCL is stretched either the most or the second most when compared to other ligaments in the lumbar spine [10]. These results then allow the FCL to be used as a gauge for ligament damage for all bending types as opposed to looking at different ligaments for each type of motion. Degeneration of the FCL can be initiated for many reasons – notably age, weight, and trauma. FCL degeneration is hypothesized to contribute to spinal instability [4, 11]. However, few studies have aimed to define the FCL’s role in providing stability to the lumbar spine. Those that do, mainly focus on all spinal ligaments as a whole, not parsing out the role of the FCL in isolation [12–14]. These investigations showed that motion was altered by removal of ligaments – increased range of motion (ROM) and decreased bending stiffness [15–17]. Alapan et al. investigated the role of each spinal ligament, independently, on the center of rotation (COR) and found when the FCL was removed the COR shifted anteriorly during flexion, unchanged during extension and lateral bending, and a slight anterior shift during axial rotation [18]. Schmidt et al. determined how the COR was related to facet joint forces, not as a function of ligamentous integrity [15]. They concluded that when the COR was located outside the disc space, the facet joint forces increased, indicating that the facets play a role in spine stability. However, COR is a two-dimensional analysis and thus assumes that coupled motions of the spine are minimal and cannot account for complex motions that occur naturally. A helical axis approach overcomes these limitations as the complete 3D motion of the spine can be described as a unique rotation about an axis, and a translation along that axis. It is a powerful analysis that can be used to understand the coupling nature of the spine, and has been used as a measure of spinal instability [19, 20]. Complementing the aforementioned study cited above [15], Schmidt et al. found that axial rotation caused the helical axes’ location to leave the disc space and that facet joint forces drove that migration [16]. While they included facet joint forces, Schmidt did not address the effect of motion on the FCL itself, which has been postulated to play a significant role in stabilizing the spine [11].

Figure 1. FE Model of Lumbar Spine.

Lumbar spine model which includes 7 spinal ligaments: Anterior Longitudinal Ligament, Posterior Longitudinal Ligament, Facet Capsular Ligament, Intertransverse Ligament, Supraspinous Ligament, Interspinous Ligament, and Ligamentum Flavum

These studies have investigated the effect of each ligament on the quantity of segmental motion and location of the two-dimensional center of rotation, but do not adequately address the quality of motion, including the arthrokinematics of the facet joint itself. Because the FCL is highly innervated, it is important to understand the local alterations, including the FCL stretch and relative facet surface motion. This could be an important mechanism of LBP, whereas the loss of FCL mechanical competency leads to an increased stretch and nerve response, resulting in pain [21, 22]. Previous studies have investigated the effect of the removal of ligaments on spine motion [18, 23], but none investigated the effect of motion on the FCL strains or the facet joint space. Previous studies also focus on all spinal ligaments as a group [17, 18, 23, 24], the purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of the FCL alone on the mechanics of the lumbar motion segment. The FCL stretches have been considered previously [25, 26], but not the relationship of the FCL health to the motions of the spine. To quantify the impact of the FCL on spinal stability a multifaceted approach was taken that included: helical axes of motion, ROM, bending stiffness, FCL stretch, and facet joint contact patterns.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of FCL failure the mechanical behavior of the lumbar spine during different magnitudes of motion using a previously developed and validated finite element model of the L4-L5 motion segment. We hypothesized that FCL failure would result in abnormal motion profiles with altered facet joint space and FCL strain patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. FE Model

A previously developed, published, three-dimensional Finite Element (FE) model of a human lumbar spine segment was used for this study (Figure 1) [23]. Briefly, the geometry of the L4 and L5 vertebrae was extracted from a computed tomography (CT) scan of a 52-year-old male human cadaveric spine that was screened radiographically for anatomical anomalies. It is important to note that this model has subject specific geometry, and therefore a natural asymmetry and variability in anatomy is present. The vertebral bodies were segmented in Mimics (v12.3 Materialise; Ann Arbor MI), and intervertebral disc was generated using the wrap function in 3-matic (Materialise; Ann Arbor, MI) [23]. The 3-D geometry was meshed using Hypermesh (v10.0 Altair Engineering, Inc; Troy, MI), and evaluated using ABAQUS (v6.13, Dassault Systemes; Providence, RI). The nucleus pulposus was surrounded by seven annulus fibrosus lamellae, which were modeled as a solid matrix with embedded fibers oriented in concentric rings. The fibers in the disc and all fibers in the ligaments were defined using 3-D two-node truss elements. The ligaments in this model were defined as non-linear hypoelastic material, which allows the stiffness to be a function of the strain of the element. And all ligament cross sectional areas were taken from literature and can be seen in Table 1 [23]. The articular surfaces of the facets were lined with a thin layer of cartilage that was simulated in ABAQUS with a softened contact parameter, and the facet joint cartilage contact was assigned zero friction during surface slippage. The softened contact parameter adjusts the force transfer between the nodes exponentially and is dependent on the initial gap size of 0.1 mm [27]. As the gap closes the stiffness of the joint is assumed to be the same stiffness of the surrounding bone [28]. The facets were modeled as healthy and the disc was mildly degenerated [23]. The ligaments (Figure 1) were assigned non-linear hypoelastic material properties (Table 1). Of critical importance to this study is the properties of the FCL, the Young’s modulus ranged from 7.5 – 33.0 MPa [26, 29, 30], and its mechanical behavior is consistent with currently published literature investigating the properties of the FCL during uniaxial extension testing [31].

Table 1:

Material properties used to define the FE model [23].

| Element Set | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio, ν | Cross-Sectional Area (mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Bone[30, 46] | 12000 | 0.30 | |

| Cancellous Bone[30, 46] | 100 | 0.20 | |

| Bony Endplate[47, 48] | 4000 | 0.30 | |

| Posterior[30, 46] | 3500 | 0.25 | |

| Annular Layers[48–50] | Neo-Hookean C10 = 0.25 – 1.13 D1 = 0.16 – 0.78 |

||

| Annular Fibers[30, 51] | 71.5 – 110 | 0.30 | 0.0743 – 0.256 |

| Nucleus Pulposus[48–50] | 1 – 1.66 | 0.40 – 0.499 | |

| Cartilage Endplate[52] | 5 | 0.17 | |

| Facet Joints[48] | Softened, 3500 | ||

| ALL[30, 53] | 15.6 – 20.0 | 0.3 | 66 |

| PLL[30, 53] | 10.0 – 20.0 | 0.3 | 25 |

| ITL[30] | 12.0 – 58.7 | 0.3 | 2 |

| LF[30, 53] | 13.0 – 19.5 | 0.3 | 39 |

| ISL[26, 30, 53] | 9.8 – 12.0 | 0.3 | 30 |

| SSL[30, 53] | 8.8 – 15.0 | 0.3 | 30 |

| FCL[26, 29, 30] | 7.50 – 33.0 | 0.3 | 44 |

2.2. Loading Conditions

Flexion, extension, right lateral bending, and right axial rotation were simulated with a compressive follower load (1000 N) [32–34] representative of body weight [35] and bending moment applied to the superior vertebral body (L4). The inferior body (L5) was fixed in all directions. Two magnitudes of the bending moment, 10 Nm, which is within the limit of physiological motion of daily activities, and 15 Nm, which is representative of heavy lifting [32, 36, 37].

To investigate the role of the FCL on spinal motion, bilateral FCL removal was simulated by diminishing the FCL modulus from its initial range (7–33 MPa, Table 1) [23] to a negligible value (100μPa). The negligible value chosen was shown with a parameter sweep to be small enough to have an effective Young’s modulus of zero, essentially removing those truss elements from the model, but retaining the ability to measure stretch.

2.3. Analysis

To calculate the helical axes of motion the anatomical coordinate system of each vertebral body was based on the following landmarks: anterior superior, posterior superior, and the most left and right lateral points on the superior vertebral bodies. Each bending movement was broken into 50 steps and the helical axis of motion was computed between each step, thus showing the pathway of motion rather than a single averaged rotational axis [38]. The final 70% of the helical axes vectors were included in the analysis. ROM of L4 relative to L5 was defined as the angular change from the neutral position to the end of the applied moment. ROM was calculated at each step and used to generate angle-moment curves; bending stiffness was calculated from the slope of the final linear portion of the angle-moment curve [28, 39].

The facet joint space was calculated by tracking the nodes of the facet surfaces and using an in-house code to calculate the 3-D Euclidean distance between the surfaces (MATLAB 9.1.0, The MathWorks Inc.). The distances were then normalized to the facet joint space of the initial time step of the bending moment (following application of the follower-load), in order to compare percentage of distance change. The lambda value of each truss element (n=36 for the right FCL and n=34 for the left FCL) was output from ABAQUS and the Green Strain was calculated for each element. The zero-strain state was considered to be after the compression step was completed. The average and standard deviation of each FCL was calculated using MATLAB (v 9.1.0, The MathWorks Inc.).

3. Results

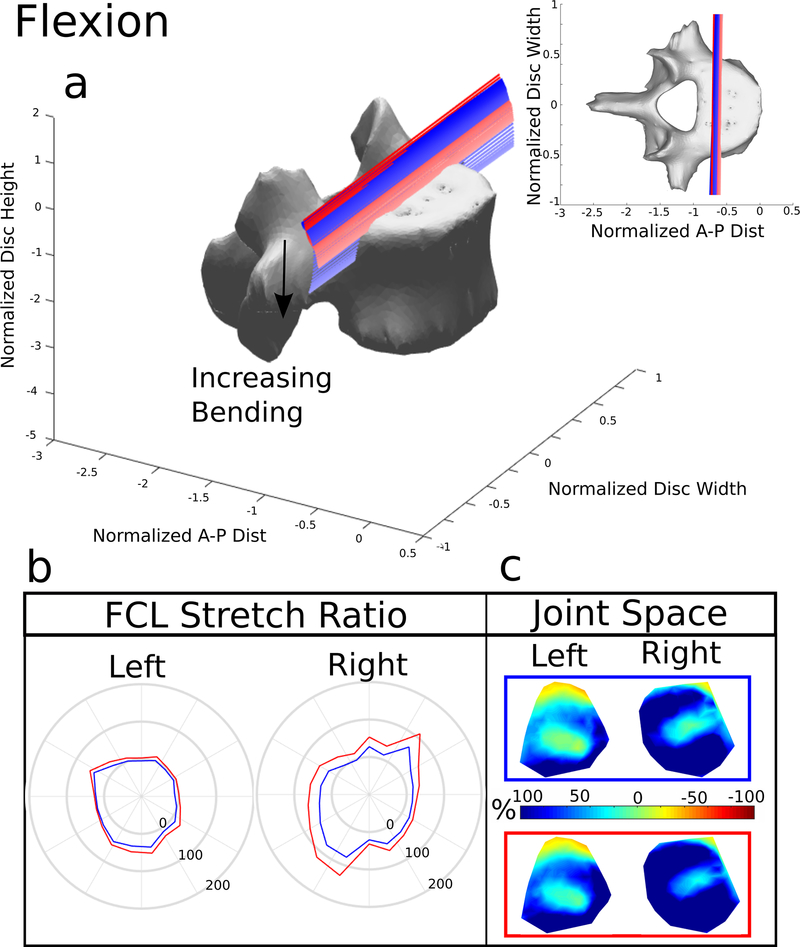

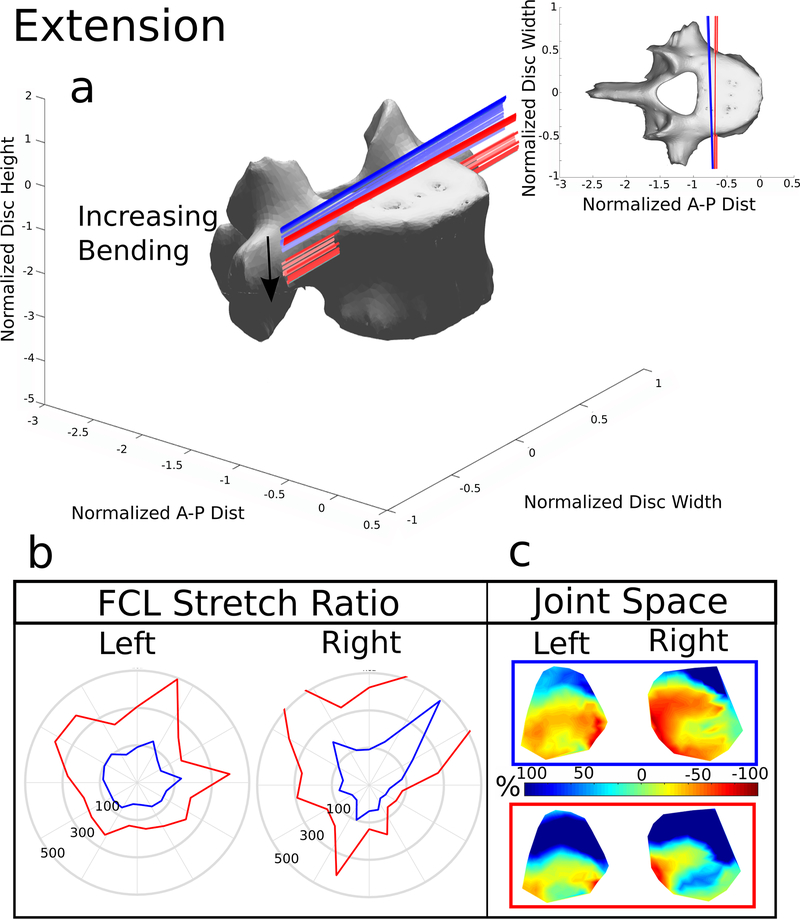

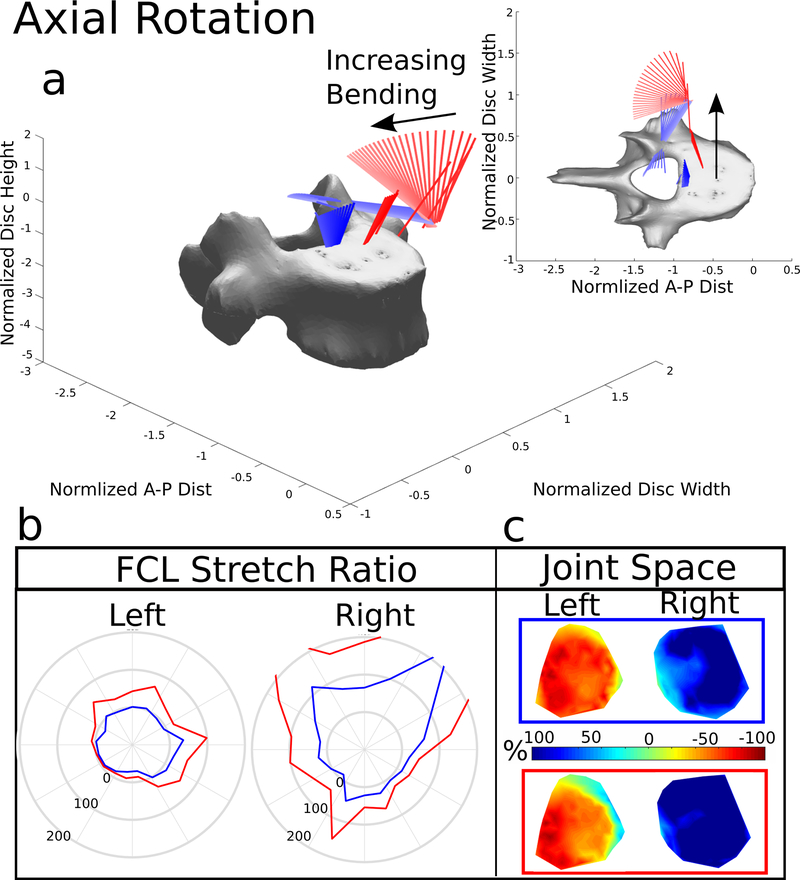

For brevity, only the 15 Nm bending models will be discussed; the 10 Nm data is available as Online Resources 1–4. Figures 2, 4–6 include the helical axes, FCL stretch with the FCL intact (blue lines) and without the FCL (red lines), and joint space minimum distance maps for the two simulations, one with the FCL present (blue boxes and helical axes) and one with the FCL removed (red boxes and helical axes). The FCL stretch is calculated for each truss element and is plotted as a function of position around the facet surface (Figures 2,4–6b). The average and standard deviation of the stretch is also reported for each FCL (Figure 7). The results discussed below all focus on the difference between the model simulations with and without the FCL present.

Figure 2. Flexion.

(a) The helical axes change in color from dark to light with increasing motion and the blue lines indicate the helical axes of motion for the model with the FCL intact, and the red lines indicate the response to the same 15 Nm bending load without the FCL present. (b) Stretch of the FCL as a function of position surrounding the facet surface. The top of the polar plot is the superior point of the facet surface and shows the value of the ligament stretch at the point. The blue line represents the model with the FCL intact and the red line indicates the model with the FCL removed. (c) Joint space calculated and normalized to the initial distance after the compression follower load. −100% (Red) indicates that the joint space is smaller and 100% (Blue) indicates that the joint space is larger. The blue box indicates the FCL was present, the red box means the FCL was removed

Figure 4. Extension.

(a) The helical axes change in color from dark to light with increasing motion and the blue lines indicate the helical axes of motion for the model with the FCL intact, and the red lines indicate the response to the same 15 Nm bending load without the FCL present. (b) Stretch of the FCL as a function of position surrounding the facet surface. The top of the polar plot is the superior point of the facet surface and shows the value of the ligament stretch at the point. The blue line represents the model with the FCL intact and the red line indicates the model with the FCL removed. (c) Joint space calculated and normalized to the initial distance after the compression follower load. −100% (Red) indicates that the joint space is smaller and 100% (Blue) indicates that the joint space is larger. The blue box indicates the FCL was present, the red box means the FCL was removed

Figure 6. Right Axial Rotation.

(a) The helical axes change in color from dark to light with increasing motion and the blue lines indicate the helical axes of motion for the model with the FCL intact, and the red lines indicate the response to the same 15 Nm bending load without the FCL present. (b) Stretch of the FCL as a function of position surrounding the facet surface. The top of the polar plot is the superior point of the facet surface and shows the value of the ligament stretch at the point. The blue line represents the model with the FCL intact and the red line indicates the model with the FCL removed. (c) Joint space calculated and normalized to the initial distance after the compression follower load. −100% (Red) indicates that the joint space is smaller and 100% (Blue) indicates that the joint space is larger. The blue box indicates the FCL was present, the red box and helical axes indicates the FCL was removed

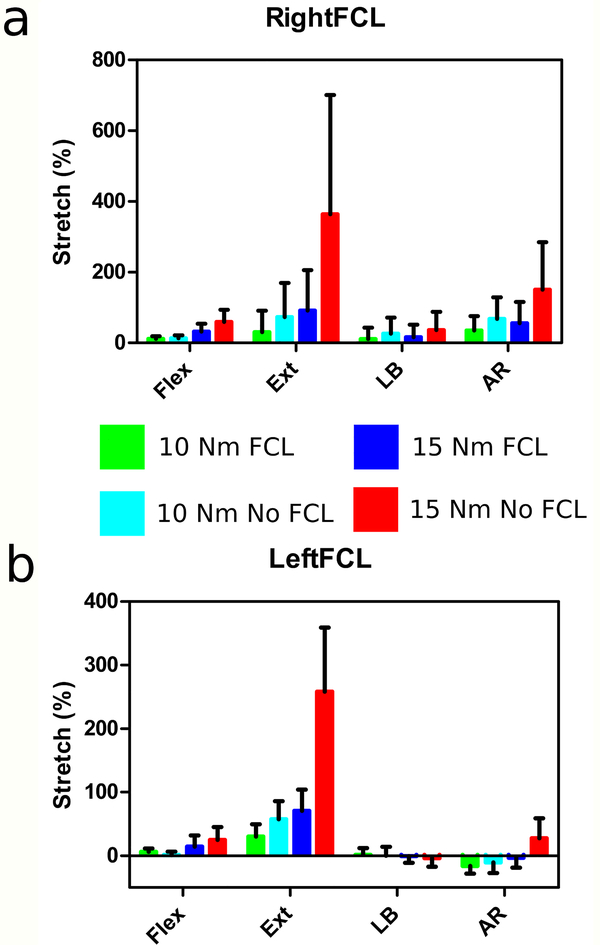

Figure 7. Average Stretch of FCLs.

(a) Right FCL the average ± std. dev. stretch of each truss element of the right FCL (n=36). (b) Left FCL the average ± std. dev. stretch of each truss element of the left FCL (n=34).

3.1. Flexion

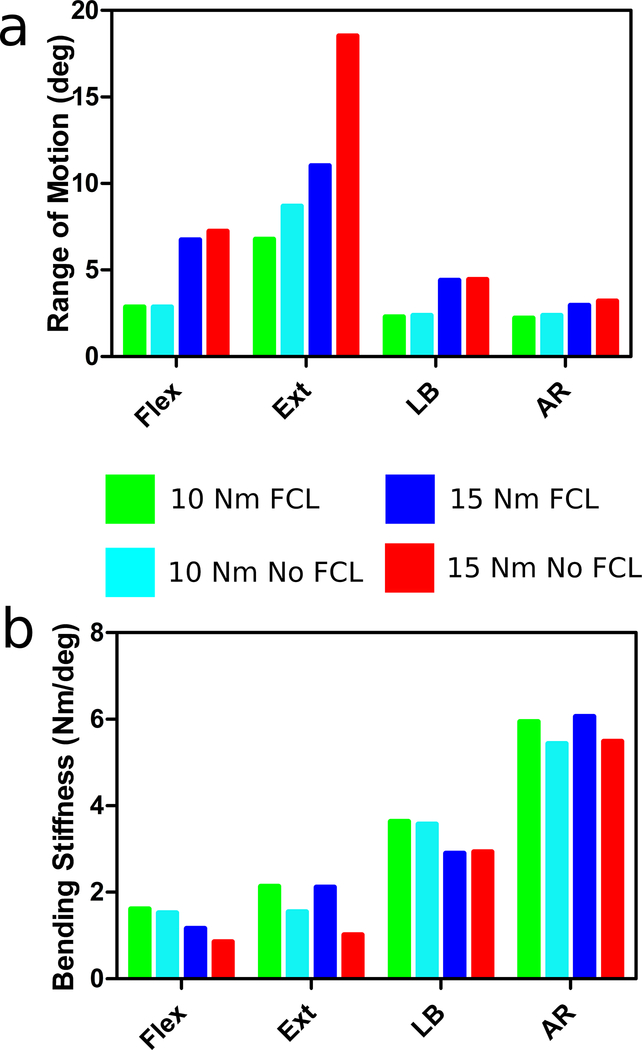

The helical axes of motion (Figure 2a) during flexion remained planar during bending. The axes moved inferiorly with the removal of the FCL because the ligament was no longer constraining the facets. Removal of the FCL resulted in a small increase in ROM of 7% and decrease in bending stiffness of 26%.

The average FCL stretch (Figure 7) was the greatest at 59.8% in the right FCL and 25% in the left FCL during15 Nm bending in the absence of the FCL. When the FCL is intact the stretches are smaller, reaching an average of 32.2% on the right and 14.3% on the left. There was asymmetry between the left and right facets and FCLs due to the anatomical asymmetry of the spine from which the FE model was generated. Based on the minimum distance maps (Figure 2c), the facets opened during flexion. As expected, the closest point was at the superior margin of each facet. The average normalized value of minimum distance when the FCL was present was 49% in the left facet and 97% on the right. The removal of the FCL increased both the left and right facet distances to 69% on the left and 121% on the right.

3.2. Extension

The helical axes during extension (Figure 4a) also remained planar. Like the flexion patterns, the removal of the FCL caused the axes to move inferiorly and anteriorly during extension. The changes caused by removal of the FCL are because no other structures in this model, such as muscles, resist the extension motion besides the anterior longitudinal ligament. The ROM approximately doubled and the bending stiffness decreased by approximately 50% (Figure 3) with removal of the FCL.

Figure 3. Range of Motion.

(a) Calculated from the rotation of the L4 relative to the L5. Bending Stiffness (b) Determined from the slope of the linear region of the ROM vs Bending Moment curves

During extension with the FCL intact the average FCL stretch was 91.9% and 70.5% on the right and left, respectively (Figure 7). Removal of the FCL increased the average stretch to 364±337% on the right and 258±100% on the left. It is important to note that the average stretches during extension also have the widest spread. The minimum distance maps of the facet joint space (Figure 4c) confirm during extension the facets close. The average normalized value from the minimum distance with the FCL present was −14% and 2% for the left and right facets. The removal of the FCL increased, because the superior facet surface slips past the inferior, to 58% and 95%, respectively.

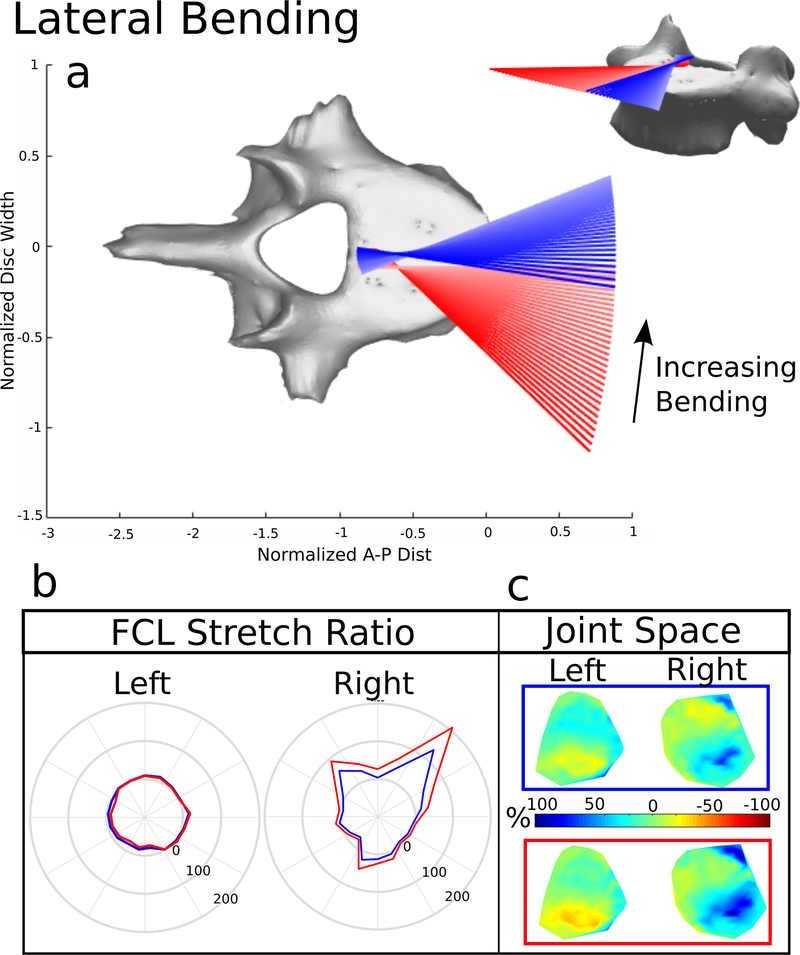

3.3. Lateral Bending

The ROM and bending stiffness for lateral bending remained unaltered with FCL removal (Figure 3). However, the helical axes were impacted (Figure 5a). For the intact segment, the axes began oriented in the anterior-posterior direction (pure lateral bending) and fan contralaterally, indicating out-of-plane or coupled motion, near the end of the ROM, When the FCL was removed, the axes shift dramatically, whereby initially there is coupled motion, followed by pure bending.

Figure 5. Right Lateral Bending.

(a) The helical axes change in color from dark to light with increasing motion and the blue lines indicate the helical axes of motion for the model with the FCL intact, and the red lines indicate the response to the same 15 Nm bending load without the FCL present. (b) Stretch of the FCL as a function of position surrounding the facet surface. The top of the polar plot is the superior point of the facet surface and shows the value of the ligament stretch at the point. The blue line represents the model with the FCL intact and the red line indicates the model with the FCL removed. (c) Joint space calculated and normalized to the initial distance after the compression follower load. −100% (Red) indicates that the joint space is smaller and 100% (Blue) indicates that the joint space is larger. The blue box and helical axes indicates the FCL was present, the red box and helical axes indicates the FCL was removed

The average FCL stretch was 16.0% in the ipsilateral facet and −0.77% on the contralateral side (Figure 7). Removal of the FCL increased the ipsilateral stretch to 36.1% and the stretch on the contralateral side to −3.79%. During the lateral bending motion the ipsilateral facet opens and the contralateral facet closes (Figure 5c). The closest point was on the inferior portion of the facet contralateral to bending. The average normalized distance with the FCL present was, on the left, 9% and 11% on the right. The removal of the FCL decreased the left facet joint space to −2% and increased the average right joint space to 23%.

3.4. Axial Rotation

Similar to lateral bending, ROM and bending stiffness were largely unaffected by the absence of the FCL (Figure 3), but the helical axes were (Figure 6a). During axial rotation, the axes originated medially near the posterior aspect of the disc space. Once the facets made contact, they became the rotational pivot point and shifted the axes laterally. With no FCL, the axes remained oriented in the inferior-superior direction but were again pushed out of the disc space when the facets made contact, but to a larger extent.

The ipsilateral FCL average stretch was 55.6%, where the contralateral facet average stretch was −3.34% (Figure 7). The removal of the FCL caused the ipsilateral FCL average stretch to increase to 150% and the contralateral FCL average stretch to increase to 27.5%. The facet joint space (Figure 6c) showed that the ipsilateral joint opens and the contralateral facet joint closes completely. The removal of the FCL again caused the facet surface to slip. With the FCL present the normalized joint space on the left was −57% and, on the right, was 88%. Removal of the FCL increased the normalized joint space to −40% on the left and 139% on the right.

4. Discussion

Previous reports have suggested the importance of FCL in flexion [40], however our data show extension ROM and stiffness was the most impacted by FCL removal (Figure 3). The quality of motion was also altered, as seen by the translation of the helical axes anteriorly and inferiorly (Figure 4a). The facet joint space maps show that the constrained the surfaces during extension; when the FCL was removed, the surfaces slipped past each other (Figure 4c), directly impacting the axis of rotation. These results indicate that the FCL is extremely important for managing spinal extension – clinically thought to be the sole role of the anterior longitudinal ligament. This role is consistent with the horizontal alignment of the collagen fibers in the FCL and their load-bearing properties [31]. Removal of the FCL did not alter motion much in flexion, likely because the interspinous, intertransverse, and supraspinous ligaments compensated for the altered mechanics. In general removal of the FCL would distribute the loads to other structures in the model. Flexion did not have a large difference in motion with the removal of the FCL so it is likely that there would be no change in load distribution. During extension, the anterior longitudinal ligament and the intervertebral disc would have been recruited.

During lateral bending, FCL removal caused noticeable changes in helical axis orientation (Figure 5a), highlighting its role in stabilization. With the FCL present, the helical axes were as previously reported (shifting to the contralateral side with an increasing rotation/flexion component during bending) [16, 20]. Without the FCL present, the axes initiated near the lateral portion of the disc and contralaterally shifted back towards the mid-line. Interestingly, there were no changes observed to ROM or bending stiffness (Figure 3). Facet joint space maps showed that the surfaces undergo asymmetric gliding when the FCL is present, and the asymmetry is more pronounced with the removal of the FCLs (Figure 5c). Removal of the FCL during lateral bending would recruit the intertransverse ligaments and the intervertebral disc and axial rotation would show a recruitment of the fibers present in the annulus fibrosis in the intervertebral disc.

Similar to lateral bending, diminishing the mechanical properties of the FCL did not affect the ROM or stiffness of axial rotation, but did have a pronounced effect on the helical axes. The facet joint space maps (Figure 6c) show that the facets on the contralateral side close completely and effectively generate a pivot point. This shifts the axes of rotation outside the joint space potentially compromising the spinal cord.

Similar to the data presented here, Alapan et al. showed minimal changes in ROM during lateral bending and axial rotation when the FCL was removed [18]. However, that was after they removed the supraspinous, intraspinous, ligamentum flavum, and intertranserse ligaments, all of which remained intact in our simulations. Heuer et al. [24] showed, for a 10Nm bending moment, a slight increase in ROM during flexion, extension, and axial rotation and no difference in ROM during lateral bending. The 10Nm ROM data (Figure 3) show slight increases in extension, and axial rotation and no changes in flexion or lateral bending. Li et al.[41] investigated the spinal mechanics of L1-L2 vertebrae both with and without the FCL present. Li et al. showed that the ROM in the flexion-extension and lateral bending increased with the removal of the FCL, and axial rotation was not affected by the removal of the FCL. Similarly, our data show that the axial rotation ROM was not as affected by the removal of the FCL, but flexion-extension was.

When comparing the results reported in this work to Schmidt et al. [15, 16] we have similar results during pure flexion, the facets remained relatively unloaded. During extension Schmidt et al. reported the location of pressure was on the inferior boarder, towards the lateral edges of the facets, our data would indicate a similar region would have the highest pressure applied [16]. Further, they showed that during axial rotation the pressure on the facet surface was localized to the lateral boarder of the contralateral facet, the data reported here suggests that the entire facet could have pressure with the highest point localized along the lateral boarder [16]. These similarities would suggest the areas of highest pressure when the FCL is removed would follow a similar pattern reported herein.

For the FCL to serve a proprioceptive role, which has been suggested by previous works [21, 22], there must be sufficiently large strains in the tissue to trigger a neuronal response. In this work, we found large stretches for loading levels in all types of bending, which may play an important physiological role - as it is known the FCL contains proprioceptive nerves [8]. Thus, the FCL has the potential to serve effectively as a proprioceptive sensor. As the mechanical integrity of the FCL diminishes, a substantial increase in FCL stretch was observed, which provides insight into the pain mechanism of spinal instability. Additionally, joint contact is an important indicator of potential pressure points on the facet surfaces caused by motions[42]. Pressure points and joint contact could be another component of the mechanosensation of the joint with feedback for the health of the bone and cartilage of the facet joint. Further research into the degeneration of the entire joint is needed to understand how all these components are interconnected and how they affect low back pain.

We note certain limitations of this computational model. First, only one L4-L5 anatomical model was used. Although we consider the use of a single model appropriate given the expense and effort required to generate multiple models, we also recognize that every individual’s vertebrae are different, so our results should be interpreted as a general example but not for exact quantitative prediction or application to a specific subject. Likewise, we considered ligaments with full mechanical function and complete loss of integrity, whereas for many individuals the reality is in between. This study was done to investigate the difference between two extreme cases, intact and FCL removed. As mentioned, degeneration of ligaments can be related to age, however depending on the individual and the original slack in each ligament, there are situations where an individual may strain or over-use the FCL in isolation – particularly in extension and axial rotation. Therefore, the authors do feel this situation is relevant and of importance to the spine field as new information regarding the importance of FCL in pain and proprioception signaling is emerging. In this context, our results should be viewed as elucidating the FCL’s role, not examining intermediate stages of tissue degeneration, which will be the focus of subsequent studies.

It is recognized that lumbar FCL damage and degeneration may not be symmetric, as was assumed in the current study. Although we focused here on symmetric changes, and a detailed study of asymmetric damage would be beyond our current scope, it would be possible to explore asymmetric changes in the future. Such changes could be particularly important in terms of load distribution between the healthy and damaged FCL under conditions, such as flexion/extension, that involve the facet joints symmetrically; an asymmetry in the FCL properties would lead to the generation of a moment, which would need to be balanced by increasing other tissue loads within the motion segment. We would also expect an asymmetry in FCL properties to lead to a pronounced difference in the motion segment’s response to a spinal rotation moment, which places much more load on one FCL than the other. Based on our model, we would expect rotation ipsilateral to the affected FCL to have a large effect because the affected would be a major load-bearer (Figure 6) but rotation contralateral to the affected FCL would have little effect since that FCL is bearing almost no load anyway (Figure 6).

Second, the FCL was modeled as a collection of truss elements (n=36 for the right and n=34 for the left), capable of supporting loads along their linear direction. Although such a model is reasonable and is consistent with the general bone-to-bone alignment of fibers in the FCL [15–18], the tissue architecture is extremely complex, and in-plane shear stresses and strains during equibiaxial loading [7, 43–45] would not be captured by bone-to-bone trusses. The average stretch (Figure 7) is reported here because this is what would have the most impact of the ligament mechanics, however there are 2 trusses that had a much shorter initial length due to the geometry of the facets and thus had much higher stretches. However, the facet surfaces of this model can be used as boundary conditions for a more detailed model of the FCL which includes fiber families in the ligament and physiologic geometries. This would be a multi-scale approach that would combine a 3D finite element model of the FCL and the motion segment model used in this study. The combination of the two models with fiber and neuron data can be used to simulate motions and show their effect on the stretch of the axons.

These data highlight the importance of the FCL in maintaining spinal stability, where diminished mechanical integrity of the FCL alone can cause a change both in the quantity as well as the quality of motion. Therefore, damage to the FCL alone may manifest as lumbar instability and the increase in FCL stretch provides support for the potential pain mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding provided through National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K12HD073945, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases T32AR050938 Musculoskeletal Training Grant, and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering U01EB016638. The authors would like to acknowledge Hugo Giambini, PhD, Miranda Shaw, PhD, and Ryan Breighner, PhD for their aid in the development of the model.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Emily A. Bermel, Department of Biomedical Engineering, 312 Church St. SE, 7-105 Nils Hasselmo Hall, Minneapolis, MN 55455, berme010@umn.edu, Phone: 612-626-9032, Fax: 612-626-6583.

Victor H. Barocas, Department of Biomedical Engineering, 312 Church St. SE, 7-105 Nils Hasselmo Hall, Minneapolis, MN 55455, baroc001@umn.edu, Phone: 612-626-5572, Fax: 612-626-6583.

Arin M. Ellingson, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, 420 Delaware St. SE, MMC 388, Minneapolis, MN 55455, ellin224@umn.edu, Phone: 612-625-1471, Fax: 612-625-4274.

References

- 1.Dagenais S, Caro J, and Haldeman S, A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J, 2008. 8(1): p. 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, and Martin BI, Back Pain Prevalence and Visit Rates: Estimates From U.S. National Surveys, 2002. Spine, 2006. 31(23): p. 2724–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panjabi MM, Clinical spinal instability and low back pain. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 2003. 13(4): p. 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izzo R, et al. , Biomechanics of the spine. Part II: spinal instability. Eur J Radiol, 2013. 82(1): p. 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varlotta GP, et al. , The lumbar facet joint: a review of current knowledge: part 1: anatomy, biomechanics, and grading. Skeletal Radiol, 2011. 40(1): p. 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claeson AA and Barocas VH, Computer simulation of lumbar flexion shows shear of the facet capsular ligament. Spine J, 2017. 17(1): p. 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ban E, et al. , Collagen Organization in Facet Capsular Ligaments Varies with Spinal Region and with Ligament Deformation. J Biomech Eng, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh J, Neural Mechanisms of Lumbar Pain. SPINE, 1995. 20(16): p. 1804–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashton IK, et al. , Morphological Basis for Back Pain: The Demonstration of Nerve Fibers and Neuropeptides in the Lumbar Facet Joint Capsule but Not in Ligamentum Flavum. J Ortho Res, 1992. 10: p. 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panjabi MM, Goel VK, and Takata K, Physiologic Strains in the Lumbar Spinal Ligaments. SPINE, 1982. 7(3): p. 192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panjabi MM, A hypothesis of chronic back pain: ligament subfailure injuries lead to muscle control dysfunction. Eur Spine J, 2006. 15(5): p. 668–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma M, Langrana NA, and Rodriguez J, Role of Ligaments and Facets in Lumbar Spinal Stability. SPINE, 1995. 20(8): p. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cusick JF, et al. , Biomechanics of sequential posterior lumbar surgical alterations. J Neurosurg, 1992. 76: p. 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillespie KA and Dickey JP, Biomechanical Role of Lumbar Spine Ligaments in Flexion and Extension: Determination Using a Parallel Linkage Robot and a Porcine Model. SPINE, 2004. 29(11): p. 1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt H, et al. , The relation between the instantaneous center of rotation and facet joint forces - A finite element analysis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2008. 23(3): p. 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt H, Heuer F, and Wilke H-J, Interaction between finite helical axes and facet joint forces under combined loading. SPINE, 2008. 33(25): p. 2741–2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alapan Y, et al. , Load sharing in lumbar spinal segment as a function of location of center of rotation. J Neurosurg Spine, 2014. 20: p. 542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alapan Y, et al. , Instantaneous center of rotation behavior of the lumbar spine with ligament failure. J Neurosurg Spine, 2013. 18: p. 617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellingson AM, et al. , Instantaneous helical axis methodology to identify aberrant neck motion. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2013. 28(7): p. 731–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellingson AM and Nuckley DJ, Altered helical axis patterns of the lumbar spine indicate increased instability with disc degeneration. J Biomech, 2015. 48(2): p. 361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarei V, et al. , Tissue loading and microstructure regulate the deformation of embedded nerve fibres: predictions from single-scale and multiscale simulations. J R Soc Interface, 2017. 14(135). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavanaugh JM, et al. , Pain Generation in Lumbar and Cerivical Facet Joints. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 2006. 88-A: p. 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellingson AM, et al. , Comparative role of disc degeneration and ligament failure on functional mechanics of the lumbar spine. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin, 2016: p. 1009–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heuer F, et al. , Stepwise reduction of functional spinal structures increase range of motion and change lordosis angle. J Biomech, 2007. 40(2): p. 271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ianuzzi A, et al. , Human lumbar facet joint capsule strains: I. During physiological motions. Spine J, 2004. 4(2): p. 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pintar FA, et al. , Biomechanical Properties of Human Lumbar Spine Ligaments. J Biomech, 1992. 25(11): p. 1351–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shirazi-Adl A, Finite-Element Evaluation of Contact Loads on Facets of an L2-L3 Lumbar Segment in Complex Loads. SPINE, 1991. 16(6): p. 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellingson AM, et al. , Disc degeneration assessed by quantitative T2* (T2 star) correlated with functional lumbar mechanics. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2013. 38(24): p. E1533–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panjabi MM, et al. , Three-dimensional quantitative morphology of lumbar spinal ligaments. Journal of spinal disorders, 1991. 4(1): p. 54–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goel VK, et al. , Interlaminar Shear Stresses and Laminae Separation in a Disc. Finite Element Analysis of the L3-L4 Motion Segment Subjected to Axial Compressive Loads. SPINE, 1995. 20(6): p. 689–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little JS and Khalsa PS, Material Properties of the Human Lumbar Facet Joint Capsule. J Biomech Eng, 2005. 127(1): p. 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naserkhaki S, et al. , Effects of eight different ligament property datasets on biomechanics of a lumbar L4-L5 finite element model. J Biomech, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izzo R, et al. , Biomechanics of the spine. Part I: spinal stability. Eur J Radiol, 2013. 82(1): p. 118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilke H-J, et al. , New In Vivo Measurements of Pressures in the Intervetebral Disc in Daily Life. SPINE, 1999. 24(8): p. 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patwardhan AG, Meade KP, and Lee B, A Frontal Plane Model of the Lumbar Spine Subjected to a Follower Load: Implications for the Role of Muscles. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 2001. 123(3): p. 212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto I, et al. , Three-Dimensional Movements of the Whole Lumbar Spine and Lubosacral Joint. SPINE, 1989. 14(11): p. 1256–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolan P and Adams MA, Repetitive lifting tasks fatigue the back muscles and increase the bending moment acting on the lumbar spine. J Biomech, 1998. 31: p. 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woltring H, et al. , Instantaneous Helical Axis Estimation from 3-D Video Data in Neck Kinematics for Whiplash Diagnostics. J Biomech, 1994. 27(12): p. 1415–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilke H, Wenger K, and Claes L, Testing criteria for spinal implants: recommendations for the standardization of in vitro stability testing of spinal implants. Eur Spine J, 1998. 7: p. 148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams M and Hutton W, The Mechanical Function of the Lumbar Apophyseal Joints. SPINE, 1983. 8(3): p. 327–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Byrne RM, et al. , Segmental Variations In Facet Joint Translations During I n Vivo Lumbar Extension. Journal of Biomechanics, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaumard NV, Welch WC, and Winkelstein BA, Spinal Facet Joint Biomechanics and Mechanotransduction in Normal, Injury and Degenerative Conditions. J Biomech Eng, 2011. 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagel TM, et al. , Combining displacement field and grip force information to determine mechanical properties of planar tissue with complicated geometry. J Biomech Eng, 2014. 136(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Claeson AA and Barocas VH, Planar biaxial extension of the lumbar facet capsular ligament reveals significant in-plane shear forces. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2016. 65: p. 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarei V, et al. , Image-based multiscale mechanical modeling shows the importance of structural heterogeneity in the human lumbar facet capsular ligament. Biomech Model Mechanobiol, 2017. 16(4): p. 1425–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirazi-Adl SA, Shirvastava SC, and Ahmed AM, Stress Analysis of the Lumbar Disc-Body Unit in Compression. A Three-Dimensional Nonlinear Finite Element Study. SPINE, 1984. 9(2): p. 120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edwards WT, et al. , Structural Features and Thickness of the Vertebral Cortex in the Thoracolumbar Spine. SPINE, 2001. 26(2): p. 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmidt H, et al. , Application of a calibration method provides more realistic results for a finite element model of a lumbar spinal segment. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2007. 22(4): p. 377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Natarajan RN, Williams JR, and Andersson GBJ, Recent Advances in Analytical Modeling of Lumbar Disc Degeneration. SPINE, 2004. 29(23): p. 2733–2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruberte LM, Natarajan RN, and Andersson GB, Influence of single-level lumbar degenerative disc disease on the behavior of the adjacent segments--a finite element model study. J Biomech, 2009. 42(3): p. 341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skaggs DL, et al. , Regional Variation in Tensile Properties and Biochemical Composition of the Human Lumbar Anulus Fibrosus. SPINE, 1994. 19(12): p. 1310–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson SJ, Ito K, and Nolte L-P, Fluid flow and convective transport of solutes within the intervertebral disc. Journal of Biomechanics, 2004. 37(2): p. 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chazal J, et al. , Biomechanical properties of spinal ligaments and a histological study of the supraspinal ligament in traction. Journal of Biomechanics, 1985. 18(3): p. 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.