Abstract

Introduction

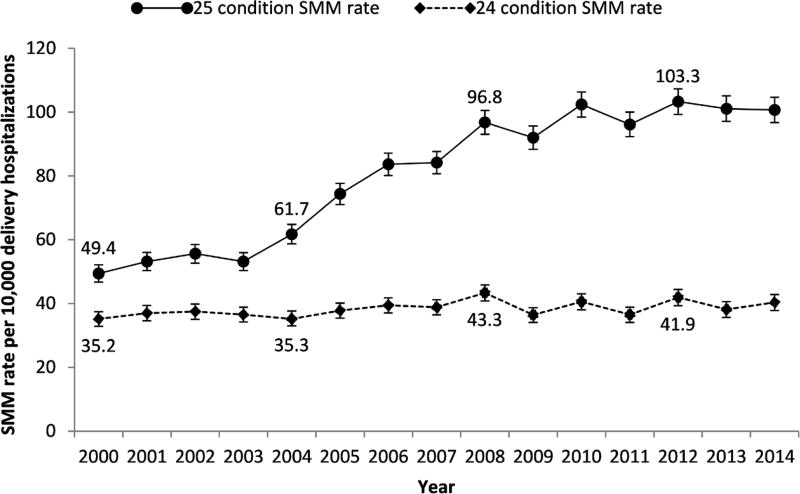

Severe maternal morbidities include 25 complications resulting from, or exacerbated by, pregnancy. Nationally, in the last decade, these rates have doubled.

Objective

This study describes trends in the rates of severe maternal morbidities at the time of hospitalization for delivery among different groups of Wisconsin women.

Methods

Hospital discharge data and ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes were used to identify delivery hospitalizations and rates of severe maternal morbidity among Wisconsin women from 2000 to 2014. Subsequent analyses focused on recent years (2010–2014). Rates of severe maternal morbidity were calculated per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations for all 25 severe maternal morbidity conditions as well as 24 conditions (excluding blood transfusions). Rates and rate ratios were calculated overall and for racial/ethnic groups, age groups, public health region of residence, and hospital payer. Median hospital length of stay and median hospital charges were compared for delivery hospitalizations with increasing severe maternal morbidities.

Results

Severe maternal morbidity rates increased 104% from 2000 to 2014 (P for trend <0.01). After excluding blood transfusions, rates increased 15% (P for trend <0.05). From 2010 to 2014, overall rates were stable over time, but varied by maternal age, race/ethnicity, payer, and public health region of residence. Median hospital charges and length of stay increased as the number of morbidities increased.

Conclusions

Monitoring severe maternal morbidities adds valuable information to understanding perinatal health and obstetric complications in order to identify opportunities for prevention of severe morbidities and improvements in the quality of maternity care.

INTRODUCTION

Considerable progress has been made in the United States to reduce pregnancy-related deaths.1 This is reflected in Wisconsin, where maternal mortality remains below the national average (16.0 per 100,000 live births) at 5.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.2 Though maternal deaths are relatively rare, it is estimated that for each death another 50 women experience serious complications related to pregnancy.3 While maternal deaths traditionally have been the key indicator for maternal outcomes, the prevalence of serious pregnancy complications—or severe maternal morbidities—can provide a more comprehensive picture of perinatal health issues when examined along with maternal deaths.3,4

Nationally, there are efforts to expand maternal health surveillance beyond maternal death to severe maternal morbidity, which may have both short- and long-term consequences for childbearing women.5 Included in these efforts is the development of a standardized measure that utilizes diagnostic codes from hospital data to identify delivery hospitalizations with at least 1 of 25 severe conditions.3–5 These conditions often are associated with long hospital stays and high medical costs at the time of delivery and, for some women, well into the postpartum period.4

In the past decade, reported severe maternal morbidity nationally has increased from 79 to 163 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations—a 106% increase—suggesting a need to improve the quality of maternal care and identify high-risk women for targeted interventions in the perinatal period.4,6 Estimating severe maternal morbidity at the state level is an important extension of this work, since state health departments are well-positioned to share the information with multiple partners who work closely with and within healthcare systems. To date, statewide surveillance of severe maternal morbidity has not been put into practice in Wisconsin, but may offer insights for identifying opportunities to prevent maternal deaths and address quality in perinatal care.3 This analysis utilizes the standardized measure for severe maternal morbidity to describe temporal trends and identify groups at increased risk in Wisconsin.

METHODS

Wisconsin’s hospital discharge data was used to identify delivery hospitalizations to Wisconsin women from 2000 to 2014. This data contains hospital admission and discharge encounters in Wisconsin facilities regardless of payer. In addition, delivery hospitalizations for Wisconsin residents in Minnesota facilities were included, as approximately 1,200 Wisconsin resident births (2%) and as many as 98% of births to women residing in some western Wisconsin counties occur in Minnesota facilities. Any hospitalizations of out-of-state residents in Wisconsin facilities were excluded from analysis. Delivery hospitalizations were identified with pregnancy-related International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes using methods previously described by Kuklina and colleagues.6

To identify delivery hospitalizations with severe maternal morbidity, 25 conditions present at the time of delivery hospitalization among Wisconsin residents were identified with ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes using methods described by Callaghan and colleagues.4 A severity recalculation was applied to account for implausibly short length of hospital stay, such that delivery hospitalizations identified by diagnosis codes were reclassified as non-severe maternal morbidity delivery hospitalizations if the length of stay was less than the 90th percentile.4

The severe maternal morbidity rate was calculated as the number of delivery hospitalizations with at least 1 condition per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations, and the Cochran-Armitage test for linear trend was used to examine changes from 2000 to 2014. To statistically test apparent stabilization in more recent years, Joinpoint software was used to identify the best fit line for trends, including detection of any changes in the slope of the trend line over time.7

To provide a more detailed look at trends and disparities in recent years, delivery hospitalizations from 2010 to 2014 were the focus of subsequent analyses. Rates were calculated separately for each condition as well as hospital stay payer (private, Medicaid, and other—eg, all other payers including Medicare, other governmental payer, self-pay, or unknown), age categories (less than 20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–39 years, and 40 or more years), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, and non-Hispanic other), delivery type (vaginal, primary cesarean, and repeat cesarean) and public health region of residence (western, northern, northeastern, southeastern, and southern). Crude rate ratios were calculated to compare rates within these categories.

Delivery hospitalizations with severe maternal morbidity were categorized as having 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more conditions. In addition, median hospital length of stay and median total hospital charges for delivery hospitalizations with no severe maternal morbidity were compared to delivery hospitalizations across these categories. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to compare median length of stay and charges for each category compared to the category with fewer severe maternal morbidities as the comparison group (eg, 1 vs 0, 2 vs 1, and 3+ vs 2).

Two severe maternal morbidity rates were calculated across all analyses: (1) a morbidity rate including all 25 conditions, and (2) a 24-condition morbidity rate excluding blood transfusion. The 25-condition rate usually is dominated by transfusion as the leading severe maternal morbidity condition, so an examination of the 24-condition rate allows for an assessment of trends and other findings independent of the impact of transfusion.5 This comparison is valuable, as hospital discharge data does not include information about the number of units of blood transfused, and transfusions of less than 4 units may inappropriately classify delivery hospitalizations as those with severe maternal morbidity. P-values of less than 0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant for all comparisons and statistical tests. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and Joinpoint version 4.3.1.0.

RESULTS

A total of 995,179 delivery hospitalizations occurred among Wisconsin women between 2000 and 2014. Of those, 7,999 were identified with severe maternal morbidity (overall rate=80.4 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations, 95% CI=78.6, 82.2), but 1,894 (19.1%) were reclassified as non-severe maternal morbidity hospitalizations due to length of stay less than the 90th percentile. The severe maternal morbidity rate increased 103.6% between 2000 and 2014 (P for trend <0.01; see Figure), and we identified 1 point where the slope of the trend line changed significantly. While the rate increased from 2000 to 2007 (P<.01), there was no significant change from 2008 to 2014 (P=0.14). After removing blood transfusions, there were 3,812 delivery hospitalizations with severe maternal morbidity from 2000 to 2014 (overall rate=38.3, 95% CI=37.1, 39.5), with a 14.7% increase during this time period (P for trend=0.04). No changes in the slope of the trend line were identified.

Figure.

Severe Maternal Morbidity Rate, Wisconsin 2000–2014

Abbreviation: SMM, severe maternal morbidities.

From 2010 to 2014, there were 320,745 delivery hospitalizations. Of those, 3,229 were identified with severe maternal morbidity (rate=100.7, 95% CI=97.2, 104.1), and 572 (15.0%) were reclassified as non-severe maternal morbidity hospitalizations due to length of stay less than the 90th percentile. This rate remained stable during the time period (P for trend=0.90). After removing blood transfusions (24-condition rate), there were 1,266 delivery hospitalizations with severe maternal morbidity (rate=39.5, 95% CI=37.3, 41.7), a rate that remained virtually stable (percent decrease=0.6%, P for trend=0.88).

Table 1 shows the number and rate of each condition, ordered by highest rate. Among delivery hospitalizations with severe maternal morbidity, 12.8% (n=414) had more than 1 condition. Both hospital charges and length of stay increased significantly with each additional severe maternal morbidity for the 25-condition analysis (P<0.01 for each comparison), and results were similar for the 24-condition analysis with the exception of 3+ vs 2 conditions (Table 2). Table 3 shows rates and rate ratios by demographic and geographic subgroups. We observed disparities by age, race, payer, mode of delivery, and region.

Table 1.

Severe Maternal Morbidity Rates by Condition for Delivery Hospitalizations, 2010–2014

| Delivery Hospitalizations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | No. | Rate Per 10,000 Delivery Hospitalizations |

95% CI |

| Blood transfusion | 2,214 | 69.0 | 66.2, 71.9 |

| Operations on heart, pericardium, and other vesselsa | 271 | 8.4 | 7.4, 9.5 |

| Hysterectomy | 245 | 7.6 | 6.7, 8.6 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 221 | 6.9 | 6.0, 7.8 |

| Heart failure during procedure or surgery | 147 | 4.6 | 3.8, 5.3 |

| Acute renal failure | 130 | 4.1 | 3.4, 4.7 |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | 122 | 3.8 | 3.1, 4.5 |

| Ventilation | 99 | 3.1 | 2.5, 3.7 |

| Eclampsia | 85 | 2.7 | 2.1, 3.2 |

| Shock | 81 | 2.5 | 2.0, 3.1 |

| Sepsis | 62 | 1.9 | 1.5, 2.4 |

| Puerperal cerebrovascular disorders | 35 | 1.1 | 0.7, 1.5 |

| Cardio monitoring | 28 | 0.9 | 0.5, 1.2 |

| Pulmonary edema | 27 | 0.8 | 0.5, 1.2 |

| Thrombotic embolism | 27 | 0.8 | 0.5, 1.2 |

| Sickle cell anemia with crisis | 18 | 0.6 | 0.3, 0.8 |

| Internal injuries of thorax, abdomen and pelvis | 14 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.7 |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 12 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 |

| Cardiac arrest or ventricular fibrillation | 12 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 |

| Conversion of cardiac rhythm | 12 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 |

| Severe anesthesia complications | 11 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 |

| Intracranial injuries | 5 | b | b |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 4 | b | b |

| Aneurysm | 1 | b | b |

| Temporary tracheostomy | 1 | b | b |

Category has been renamed to clarify the inclusion of operations on other vessels.

Rates and CIs not calculated for severe maternal morbidity with fewer than 10 events.

Table 2.

Median and Range of Length of Hospital Stay and Hospital Charges by Number of Severe Maternal Morbidities Among Delivery Hospitalizations, Wisconsin, 2010–2014

| 25-Condition SMM | 24-Condition SMM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS (Days) | Hospital Charges | LOS (Days) | Hospital Charges | |

| 0 SMM | 2 | $8,954 | 2 | $8,983 |

| 1 SMM | 3a | $18,891a | 4a | $23,619a |

| 2 SMM | 5b | $34,975b | 6b | $52,426b |

| 3+ SMM | 6c | $68,895c | 7 | $78,874c |

Abbreviations: SMM, severe maternal morbidity; LOS, length of hospital stay.

Significantly different from 0 SMM, P<0.01.

Significantly different from 1 SMM, P<0.01.

Significantly different from 2 SMM, P<0.01.

Table 3.

Severe Maternal Morbidity Rate by Demographics, Payer, and Public Health Region of Residence, Wisconsin, 2010–2014

| 25-Condition SMM | 24-Condition SMM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Delivery With SMM |

Rate Per 10,000 Delivery (Hospitalizations (95% CI) |

Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

Delivery With SMM |

Rate Per 10,000 Delivery Hospitalizations (95% CI) |

Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Age | ||||||

| < 20 | 290 | 139.6 (123.6, 155.7) | 1.6 (1.4, 1.9) | 79 | 38.0 (29.6, 46.4) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) |

| 20–24 | 670 | 98.8 (91.3, 106.2) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.3) | 190 | 28.0 (24.0, 32.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) |

| 25–29 | 866 | 85.4 (79.7, 91.1) | Reference | 332 | 32.7 (29.2, 36.3) | Reference |

| 30–34 | 833 | 93.3 (87.0, 99.7) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 366 | 41.0 (36.8, 45.2) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) |

| 35–39 | 443 | 128.4 (116.5, 140.4) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 227 | 65.8 (57.2, 74.4) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.4) |

| 40+ | 127 | 181.4 (149.8, 212.9) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.6) | 72 | 102.8 (79.1, 126.6) | 3.1 (2.4, 4.1) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,922 | 86.2 (82.3, 90.0) | Reference | 775 | 34.7 (32.3, 37.2) | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 476 | 148.0 (134.7, 161.3) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.9) | 197 | 61.3 (52.7, 69.8) | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) |

| Hispanic | 347 | 126.3 (113.0, 139.6) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.6) | 116 | 42.2 (34.5, 49.9) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander | 172 | 135.7 (115.4, 156.0) | 1.6 (1.3, 1.8) | 61 | 48.1 (36.0, 60.2) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 56 | 158.9 (117.3, 200.5) | 1.8 (1.4, 2.4) | 14 | 39.7 (18.9, 60.5) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.9) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 29 | 100.5 (63.9, 137.1) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 16 | 55.5 (28.3, 82.6) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) |

| Payer | ||||||

| Private | 1,551 | 85.1 (80.9, 89.3) | Reference | 652 | 35.8 (33.0, 38.5) | Reference |

| Medicaid | 1,548 | 120.9 (114.9, 126.9) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.5) | 543 | 42.4 (38.8, 46.0) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) |

| Other | 130 | 125.8 (104.2, 147.4) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | 71 | 68.7 (52.7, 84.7) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.5) |

| Public health region of residence | ||||||

| Western | 310 | 75.3 (66.9, 83.7) | Reference | 131 | 31.8 (26.4, 37.3) | Reference |

| Northeastern | 663 | 98.2 (90.7, 105.7) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 202 | 29.9 (25.8, 34.0) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.2) |

| Northern | 271 | 113.9 (100.3, 127.4) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) | 94 | 39.5 (31.5, 47.5) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.7) |

| Southeastern | 1,259 | 101.7 (96.1, 107.4) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.5) | 538 | 43.5 (39.8, 47.2) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) |

| Southern | 726 | 112.8 (104.6, 121.0) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 301 | 46.8 (41.5, 52.0) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) |

| Delivery type | ||||||

| Vaginal | 606 | 57.9 (54.9, 61.0) | Reference | 306 | 17.2 (15.6, 18.9) | Reference |

| Primary cesarean | 1,250 | 273.4 (258.6, 288.9) | 4.7 (4.4, 5.1) | 553 | 121.0 (111.2, 131.4) | 7.0 (6.2, 8.0) |

| Repeat cesarean | 1,373 | 159.6 (147.3, 172.7) | 2.8 (2.5, 3.0) | 407 | 80.6 (71.9, 90.0) | 4.7 (4.0, 5.4) |

Abbreviations: SMM, severe maternal morbidity.

Bold type indicates a statistically significant difference from a ratio of 1.0.

18,927 hospitalizations missing race/ethnicity (5.9%).

DISCUSSION

Our observations for the most commonly documented severe maternal morbidity conditions and increasing trend over time are consistent with other studies.3 Blood transfusions, which accounted for most of the increase in severe maternal morbidity over time, may relate to postpartum hemorrhage.3,4 It is well understood that prior cesarean delivery increases the risk for abnormal placentation in subsequent deliveries, potentially leading to hemorrhage. Further, placental abnormalities, labor induction, cesarean deliveries, and instrumental delivery have increased, which may be related to prenatal obesity and advanced maternal age.5,8–13 Increases in severe maternal morbidity nationally have been attributed to maternal factors such as obesity, cesearean delivery, and chronic health conditions.14 Publicly available data from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services indicate that the proportion of cesarean delivery births increased from 17% to 25% from 2000 to 2007 but remained stable from 2008 to 2014 (25% vs. 26%).15 Further, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a population-based survey targeting mothers with a live birth, indicates that the proportion of Wisconsin women who were obese prior to pregnancy has remained stable since 2008.16 While previous studies have identified higher risk of severe maternal morbidity for cesarean deliveries,5,14 it is unclear whether severe maternal morbidity increases the risk for cesarean delivery or vice versa. Future examination of prepregnancy maternal health may assist in understanding the relationship between severe maternal morbidity and mode of delivery.

A challenge in understanding blood transfusion trends relates to how the ICD-9-CM code is used in practice in events such as postpartum hemorrhage. This condition is often clinically defined as blood loss greater than 500 ml for a vaginal delivery and 1,000 ml for cesarean delivery,5,17 thresholds that are good predictors of the need for blood transfusion.17 However, the ICD-9-CM code for blood transfusion does not include information for important contextual details such as units of transfused blood, which may be an important indicator of severity, particularly as calls for in-hospital reviews of severe maternal morbidity suggest reviewing cases where women receive 4 or more units of blood.18 In addition, lack of detailed clinical information and changes in clinician use of blood transfusion over time further limits our ability to fully explain the increase in blood transfusions in Wisconsin.19

Our findings for median length of stay and hospital charges likely reflect that women with multiple severe maternal morbidities may tend to have more severe or complex medical complications during delivery hospitalization, which may require longer and more expensive hospital care. Of interest, median length of stay and charges were lower for 25-condition vs 24-condition severe maternal morbidity. This may reflect the predominance of blood transfusions in the 25-condition definitions such that some of those hospitalizations with only blood transfusion may be relatively minor in comparison to the other 24 conditions.

Disparities for severe maternal morbidity by demographic characteristics followed very similar patterns to those recently reported for maternal mortality in Wisconsin.2 The rare occurrence of maternal death and small population size for some racial/ethnic groups in the state prevent the ability to examine disparities in maternal mortality across all groups. Thus, severe maternal morbidity can provide a mechanism for identification of these disparities in maternal health and outcomes.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, we included only delivery hospitalizations; consequently, women hospitalized prenatally or postpartum for any of the 25 severe maternal morbidity conditions are not captured in our estimation of severe maternal morbidity burden if these conditions were not also present at delivery. Further, though we utilized a validated method for identifying severe maternal morbidity, the use of ICD-9-CM codes for the analysis may result in misclassification as coding practices can vary among medical coders by facility or over time. In addition, the severe maternal morbidity conditions described here each include multiple ICD-9-CM codes, which might obscure whether a few codes disproportionately account for the events in some categories. For example, Wisconsin’s rate for operations on the heart, pericardium, and other vessels category was substantially higher than the US rate.4 Upon examination of the ICD-9-CM codes contributing to this category, we observed that suture of artery (39.31) was the most common code within this category and very few codes were related to the heart or pericardium. Finally, hospital data does not include contextual information that could enhance the analysis. For example, there are few fields within the dataset that allow for adjustment for potential confounders beyond basic demographic information, including risk factors such as obesity, poverty status, late or no prenatal care, prior cesarean delivery, or prepregnancy medical condition.1,20–22 Consequently, differences identified by geography, demographics, and hospital payer should be interpreted cautiously, as we did not conduct analyses to adjust for confounders. Analyses utilizing hospital discharge data linked to the newborn hospitalization and birth certificate would enable a more complete exploration of contributors to differences and trends in severe maternal morbidity.1

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these limitations, our analysis of severe maternal morbidities adds to the understanding of perinatal complications in Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Maternal Mortality Review Team has been able to glean some limited information about the increased risk of chronic disease on maternal health, but continued surveillance of severe maternal morbidities would provide more in-depth understanding.2 In addition, it is important for physicians and hospitals to be aware of the trends and current distribution of severe maternal morbidities among Wisconsin mothers as they identify needs for quality improvement related to perinatal care. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that hospitals or birth facilities develop and maintain their own severe maternal morbidity review process to address opportunities for system and caregiver improvement.14 Our analyses provide important information about groups of women at risk for severe pregnancy complications, which could help identify areas for targeted intervention. Further, our use of a standard approach for identifying and tracking maternal complications provides clinicians and public health partners with a framework for exploring opportunities to improve perinatal care and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kristin Rankin, PhD, Michael Schellpfeffer, MD, and the Wisconsin Maternal Mortality Review Team for their input and assistance during preparation of this manuscript.

Funding/Support: This study was supported in part by an appointment to the Applied Epidemiology Fellowship Program administered by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement Number 1U38OT000143-03. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Author Disclosures: None declared.

Contributor Information

Crystal Gibson, Public Health Madison and Dane County, Madison, Wis.

Angela M. Rohan, Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health, Madison, Wis; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Madison, Wis.

Kate H. Gillespie, Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health, Madison, Wis.

References

- 1.Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schellpfeffer MA, Gillespie KH, Rohan AM, Blackwell SP. A review of pregnancy-related maternal mortality in Wisconsin, 2006–2010. WMJ. 2015;114(5):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan WM, Grobman WA, Kilpatrick SJ, Main EK, D'Alton M. Facility-based identification of women with severe maternal morbidity: it is time to start. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):978–981. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991–2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(2):133.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(4):469–477. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Insitute, Surveillance Research Program. [Accessed December 21, 2017];Joinpoint trend analysis software. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. Updated June 22, 2017.

- 8.Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):449.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight M, Callaghan WM, Berg C, et al. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford JB, Roberts CL, Simpson JM, Vaughan J, Cameron CA. Increased postpartum hemorrhage rates in Australia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fyfe EM, Thompson JM, Anderson NH, Groom KM, McCowan LM. Maternal obesity and postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal and caesarean delivery among nulliparous women at term: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Lieberman E, Himes KP. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes by prepregnancy body mass index: a population-based study to inform prepregnancy weight loss counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):133–143. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ovesen P, Rasmussen S, Kesmodel U. Effect of prepregnancy maternal overweight and obesity on pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):305–312. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182245d49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, et al. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: Where are we now? J Womens Health. 2014;23(1):3–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. [Accessed December 22, 2017];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://nccd.cdc.gov/pramstat/. Updated August 21, 2017.

- 16.WISH - Birth Counts Module. [Accessed December 22, 2017];Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health, Office of Health Informatics website. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/wish/birth/index.htm. Revised November 19, 2015.

- 17.Conner SN, Tuuli MG, Colvin R, Shanks AL, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Accuracy of estimated blood loss in predicting need for transfusion after delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(13):1225–1230. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1552940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilpatrick SJ, Berg C, Bernstein P, et al. Standardized severe maternal morbidity review: rationale and process. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(4):403–408. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts CL, Ford JB, Algert CS, Bell JC, Simpson JM, Morris JM. Trends in adverse maternal outcomes during childbirth: a population-based study of severe maternal morbidity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaughan DA, Cleary BJ, Murphy DJ. Delivery outcomes for nulliparous women at the extremes of maternal age – a cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121(3):261–268. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingston D, Heaman M, Fell D, Chalmers B. Comparison of adolescent, young adult, and adult women’s maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1228–37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pacheco AJ, Katz L, Souza AS, de Amorim MM. Factors associated with severe maternal morbidity and near miss in the São Francisco Valley, Brazil: a retrospective, cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]