Abstract

Context:Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & Perry (Myrtaceae), commonly known as clove, originally found in the Muluku Islands in East Indonesia, is widely used as a spice and has numerous medicinal properties.

Objective: This study investigated the antioxidant potential of S. aromaticum aqueous extract (SAAE) in vitro and its protective effects on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung inflammation in mice.

Material and methods: Neutrophils were isolated from healthy donors and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was measured by luminol-amplified chemiluminescence. Superoxide anion generation was detected by cytochrome c reduction assay. H2O2 was detected by DCFH fluorescence assay. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was mesured by tetramethyl benzidine oxidation method. To study the anti-inflammatory activity of SAAE, lung inflammation was induced in mice (BALB/c) by intra-tracheal instillation of lypopolysaccharide (5 µg/mouse), and SAAE (200 mg/kg body weight) was injected intraperitoneally prior to LPS administration. Bronchoalveolar lavage and lung tissue were collected to assess inflammatory cells count and total protein content. Metalloproteinases activity was detected by zymography technique.

Results: SAAE inhibited luminol-amplified chemiluminescence of resting neutrophils and N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine- or phorbol myristate acetate-stimulated neutrophils, with an inhibitory effect starting at a concentration as low as 0.5 µg/mL. Moreover, SAAE reduced significantly MPO activity and it exhibits a dose-dependent action (IC50 = 0.5 µg/mL). In vivo results showed that SAAE decreased markedly neutrophil count (From 61% to 15%) and proteins leakage into bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Gelatin zymography assay showed that S. aromaticum inhibited MMP-2 (15%) and MMP-9 (18%) activity in lung homogenates.

Discussion and conclusion: Our results suggest that the anti-inflammatory activity of SAAE, in vivo, is due to the inhibition of ROS production and metalloproteinases activity via its action on MPO. According to these findings, SAAE could be a potential source of new compounds with anti-inflammatory activity.

Keywords: Clove, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, reactive oxygen species, myeloperoxidase

Introduction

Inflammatory diseases are mostly the result of uncontrolled inflammation leading to damage and destruction of healthy tissue (Minihane et al. 2015). These processes involve major cells of the immune system, including macrophages, lymphocytes and especially polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Activated neutrophils release a variety of inflammatory mediators such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), proteolytic enzymes and cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF, etc), which promote severe damage in the site of inflammation (Punchard et al. 2004). Several inflammatory disorders including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphesyma, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis and cancer are considered as major health care problem. The pathophysiology of these diseases is due to inflammatory/anti-inflammatory and oxidant/antioxidant imbalance. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils play a key role in host defenses against invading microorganisms (Hampton et al. 1998), but excessive neutrophil activation participates in tissue damage associated with inflammatory disorders (Babior 1984, 2000). In response to a variety of agents, neutrophils migrate to inflammatory sites, where they release proteases, bactericidal peptides, and large quantities of ROS in a process known as the respiratory burst (Babior 1984). Oxygen reduction by neutrophil NADPH oxidase, a multicomponent enzyme system, yields superoxide anion (O2−) (El-Benna et al. 2005), while myeloperoxidase (MPO) produces hypochloric acid from hydrogen peroxide (Klebanoff 2005).

The matrix metalloproteinases especially MMP-2 and MMP-9 play an important role in these disorders notably in airway obstruction (Cataldo et al. 2003). Some inflammatory diseases notably COPD and emphysema exhibited glucocorticoid resistance, till today no specific medicine to control such disorders is available. Thus, searching for new therapies and specific targets are the main goal of scientific research (Barnes and Adcock 2009).

Since ancient times, plants have been used for therapeutic, cosmetic and nutritional purposes. In the last decades, researchers have investigated and characterized the proprieties and composition of several species herbs plants and demonstrated the rational of their use as a remedy of many health problems and disorders (Fabricant and Farnsworth 2001).

Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & Perry (Myrtaceae) commonly called clove, is an aromatic medicinal plant. Dried flower buds have been used as a spice and flavour in food but it is also used in traditional East Asian medicines especially in dental care (Milind and Deepa 2011; Cortés-Rojas et al. 2014). In addition, cloves exhibit antibacterial (Nuñez and Aquino 2012), antiviral (Hussein et al. 2000) and antifungal activities (Hamini-Kadar et al. 2014; Zore et al. 2011). Various other pharmacological properties, such as antioxidant (Lee and Shibamoto 2001), anti-inflammatory (Ahmad et al. 2012) and antitumor effects, have also been reported (Banerjee et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2014).

This work examines the effect of S. aromaticum aqueous extract (SAAE) on ROS production by human neutrophils, and its effect on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung inflammation in mice.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Ficoll and Dextran T500 were purchased from GE Healthcare. Luminol, cytochrome c, N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and Escherichia coli (O55:B6) LPS were from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France). Stock solutions of fMLF (10−2 mol/L) and PMA (1 mg/mL) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20 °C. The different solutions were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) immediately before use.

Aqueous extract of clove flower buds

Clove buds purchased from a local market of Gabes, were identified and voucher specimens are maintained in our laboratory. Aliquots of these buds were dried at 37 °C for 24 h, blended and the powder obtained was suspended in sterile saline solution (NaCl 0.9%) to have 0.1, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 µg/mL concentrations, then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 3 min. From each batch, the supernatants of different preparations of SAAE were used for the experiments. The results that were obtained with different preparations from different batches are reproducible.

Ethics statement and isolation of human neutrophils

Neutrophils were isolated from the venous blood of healthy volunteers with their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All experiments were approved by the INSERM Institutional Review Board and ethics committee. Data collection and analyses were performed anonymously. Neutrophils were isolated by Dextran sedimentation and density gradient centrifugation as previously described (El-Benna and Dang 2007). Erythrocytes were removed by hypotonic lysis. Following isolation, the cells were resuspended in an appropriate medium, such as Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). The cells were counted and their viability was determined with the Trypan blue exclusion method.

Measurement of ROS production by chemiluminescence

Isolated cells were resuspended in HBSS at a concentration of 1 million per mL. Cell suspensions (5 × 105) in 0.5 mL of HBSS containing 10 µM of luminol in the presence or absence of SAAE were preheated to 37 °C in the thermostated chamber of a luminometer (Berthold-Biolumat LB937) and allowed to stabilize. After a baseline reading, cells were stimulated with 10−6 M fMLF or 100 ng/mL PMA. Changes in chemiluminescence were measured over a 30-min period.

Measurement of superoxide production

Isolated cells were resuspended in HBSS at a concentration of 1 million per mL. Cell suspensions in 1 ml of HBSS containing 1 mg/mL cytochrome c in the presence or absence of SAAE were preheated to 37 °C in the thermostated chamber of a spectrophotometer (Uvikon) and allowed to stabilize. After a baseline reading, cells were stimulated with 10−6 M fMLF or 100 ng/mL PMA. Changes in absorbance were measured at 550 nm over a 15-min period.

Detection of H2O2

In order to investigate whether SAAE reacts directly with H2O2, SAAE was incubated in PBS with H2O2 (80 µM) during 15 min in the presence of luminol (10 µM) and the reaction was initiated by adding horseradish peroxidase (HRPO) (5U). Changes in chemiluminescence were measured over a 15-min period.

Effect of SAAE on MPO degranulation

Neutrophils were pre-incubated with 5 µg/mL cytochalasin B for 5 min, then with SAAE for 15 min at 37 °C. Immediately tubes were centrifuged, and the cell-free supernatants were stored at −80 °C. Western blot analysis was used to quantify the degranulation of MPO in resting neutrophils and after stimulation with PMA at 100 ng/mL.

Preparation of azurophilic granules and measurement of MPO activity

Neutrophils were lysed by nitrogen cavitation and the granule fraction was purified by Percol gradient centrifugation (Udby and Borregaard 2007). The granules were sonicated in 0.2% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and MPO activity was assessed by using the H2O2-dependent tetramethyl-benzedine (TMB) oxidation assay at 650 nm.

Measurement of cytochrome C oxidase and xanthine oxidase activities

To study the effect of SAAE on cytochrome C oxidase and xanthine oxidase activity, the test of reduction of cytochrome C was used. Neutrophils were incubated in presence of SAAE, then stimulated with PMA or fMLF and the activity of the enzyme was detected at 550 nm. Xanthine oxidase was also preincubated with SAAE and xanthine as enzyme substrate. The activity was measured using a spectrophotometer at 550 nm.

Animals

BALB/c mice aged 7 weeks and weighing 22–26 g were purchased from the animal facility of Faculty of sciences of Gabes. Animals were housed in standard wire-topped cages and the temperature-controlled units. Food and water were supplied ad libitum. The experiments were approved by our Institutional Committee on Animal Care and use and the experimental protocol complied with Tunisian legal requirements for animal’s studies.

Induction of lung inflammation

LPS of Escherichia coli O55: B6 (Sigma) was used to induce lung inflammation. Animals were divided randomly into four groups with 8–10 mice in each group. (1) Control group, received saline (NaCl 0.9%), (2) SAAE group, received 200 mg/kg of clove extract by intraperitoneal route (IP) and saline by intratracheal route (IT). (3) LPS group, received saline by IP route and LPS (5 µg/mouse) by IT route. (4) SAAE + LPS group, received 200 mg/kg of clove extract by IP route and LPS (5 µg/mouse) by IT route.

According to group, the mice received a first IP injection [Saline (group 1; and 3) or 200 mg/kg SAAE (group 2 and 4)] on day 0 (D0). On D1, they received a second IP injection [Saline (group 1; and 3) or 200 mg/kg SAAE (group 2 and 4)]. Three hours after the second IP injection, the mice received a cocktail of anaesthetics [75 mg/kg ketamin (Virbac Santé Animale, Carros, France) plus 1 mg/kg medetomidine (Pfizer, Paris, France)], before IT instillation [Saline (groups 1 and 3) or 5 µg LPS/mouse (groups 2 and 4)]. The mice were aroused by an IP injection of 1 mg/kg atipamezol (Pfizer), a medetomidine antagonist, and were sacraficed 24 h later.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and lung sampling

The mice were anesthetized by an IP injection of 50 mg of pentothal (Sigma) and killed by exsanguination. The lungs were lavaged twice with 1 mL of physiological saline, removed rapidly and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. The lavage fluid (2 mL) was immediately placed on ice. Free alveolar cells were recovered from the lavage fluid by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The total protein concentration in the supernatant and in the grinded lung was measured with the Quick-Start Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). The cell pellet was suspended in 150 µL of physiological saline and an aliquot was used to determine the total white cell count with a hemocytometer. For differential counts, the cell suspension was cytospun (Cytospin-2, Shandon Products Ltd, Levallois-Perret, France), fixed in methanol, and stained with Diff Quick solution (Medion Diagnostics, Plaisir, France). Three hundred cells were counted with an oil immersion lens (1000).

Zymography

Samples of total proteins, lung grinded, were separated under non-reducing conditions on 12% polyacrylamide gels containing 1 mg/mL gelatin, as described previously (Ciccocioppo et al. 2005). Gels were loaded with 4–10 µg of total proteins sample and run under Laemmli standard conditions. After electrophoresis, gels were washed twice in 100 mL of 2.5% Triton X-100 (30 min each) under constant mechanical agitation and incubated in activation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 µL Zn Cl2, 0.1 mM NaN3) at 37 °C for 72 h. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue. Visualization of MMP-2 and -9 activities was obtained by incubation of the gels in acetic acid 45% and methanol 10%, H2O and were quantified with Image J software.

Effect of SAAE on MPO activity in vivo

Clove buds were dried at 37 °C for 24 h, blended and the powder obtained was suspended in sterile saline solution (NaCl 0.9%), then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 3 min. From each batch, the supernatants of different preparations of SAAE were used for the experiments. Animals were divided into two groups (four mice in each group). Control group, received saline (NaCl 0.9%), SAAE group, received 200 mg/kg of clove extract by IP injection. Twenty-four hours later, 0.5 mL blood was withdrawn from mice, red cells were lyzed by ammonium chloride, neutrophils were counted, sonicated in PBS +0.2% CTAB and MPO activity was measured as described above using the H2O2-dependent TMB oxidation assay at 655 nm.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard error. The Newman–Keuls multiple comparisons test was used, and p values <0.05 were considered to denote significant differences.

Results

SAAE inhibits luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in human neutrophils

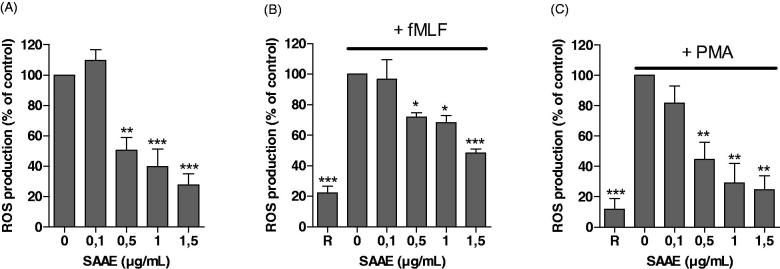

To investigate the effect of SAAE on neutrophils ROS production, human neutrophils were incubated with different SAAE concentrations and ROS were detected by luminol-amplified chemiluminescence. Results show that SAAE inhibited luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in resting neutrophils (Figure 1(A)), in neutrophils stimulated with fMLF (Figure 1(B)) and PMA (Figure 1(C)) with IC50 values of 0.5, 1.5 and 0.5 µg/mL respectively. In latter conditions, the effect of SAAE was concentration-dependent, with an inhibitory effect starting at a concentration as low as 0.5 µg/mL. As fMLF and PMA activate neutrophils through different transduction pathways, these results suggested that SAAE inhibits neutrophils ROS production by inhibiting a final common target such as the NADPH oxidase, MPO or that it scavenges ROS.

Figure 1.

Effect of SAAE on luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in human neutrophils. Human neutrophils (5 × 105) were incubated in the presence or absence of different SAAE concentrations in resting conditions (A) and stimulated with fMLF (10−6 M) (B) or PMA (100 ng/mL) (C). Luminol-amplified chemiluminescence was measured for 30 min (mean ± SEM of three experiments, *p < 0.05).

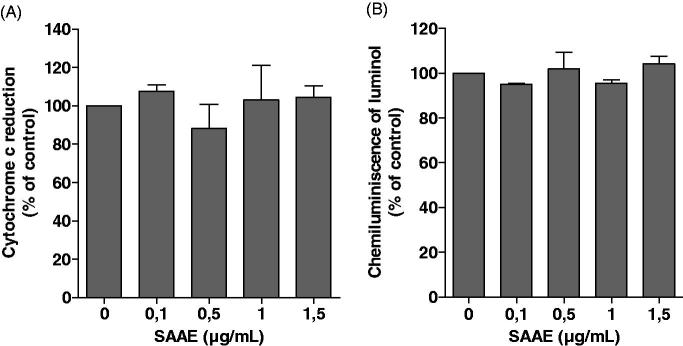

SAAE has no effect on neutrophil superoxide production

To investigate the effect of SAAE on NADPH oxidase activity, we studied its effect on superoxide anion production by using the cytochrome c reduction assay, a specific technique to assess the activity of NADPH oxidase. As shown in Figure 2, SAAE had no effect on cytochrome c reduction by human neutrophils stimulated with fMLF (Figure 2(A)) or PMA (Figure 2(B)), suggesting that it does not affect NADPH oxidase activity nor scavenge superoxide anions.

Figure 2.

Effect of SAAE on superoxide anion production by neutrophils. Human neutrophils (106) were incubated in the presence or absence of SAAE, and stimulated with fMLF (10−6 M) (A) or PMA (100 ng/mL) (B). Cytochrome c reduction was measured at 550 nm in a spectrophotometer for 15 min (mean ± SEM of three experiments, *p < 0.05).

SAAE does scavenge superoxide anion nor H2O2

Firstly, to investigate whether SAAE scavenges superoxide anions, xanthine/xanthine oxidase was used to produce superoxide anions, which were then detected by the cytochrome c reduction assay. Results show (Figure 3(A)) that SAAE had no effect on superoxide anions production by this system. Secondly, to investigate whether SAAE scavenges H2O2, SAAE was incubated in the presence of commercial H2O2 for 10 min, the reaction was started by the addition of HRP and luminol-amplified chemiluminescence was measured. Results show (Figure 3(B)) that SAAE had no effect on H2O2.

Figure 3.

Effect of SAAE on superoxide anions and H2O2in vitro. (A) Xanthine oxidase was incubated in the presence or absence of SAAE, xanthine was added and superoxide anions were detected by the cytochrome c reduction assay. (B) H2O2 was incubated in the presence or absence of SAAE and detected using HRP-amplified chemiluminescence (mean ± SEM of three experiments, *p < 0.05).

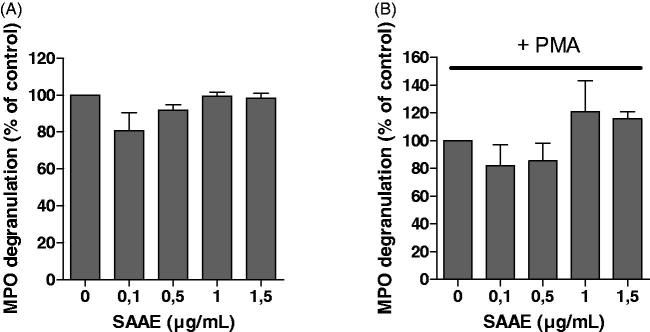

Effect of SAAE on MPO activity from azurophilic granules

As luminol-amplified chemiluminescence is dependent on MPO activity, the effect of SAAE on MPO activity was tested. Azurophilic granules extracts were incubated with different concentrations of SAAE, and MPO activity was measured using H2O2-TMB oxidation assay. As shown in Figure 4, SAAE inhibited MPO activity in a concentration-dependent manner with IC50 of 0.5 µg/mL. These results suggest that SAAE inhibits luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in neutrophils by inhibiting MPO activity.

Figure 4.

Effect of SAAE on MPO activity. MPO was incubated with or without SAAE and its activity was measured in terms of tetra-methylbenzidine oxidation at 655 nm (mean ± SEM of three experiments, *p < 0.05).

Effect of SAAE on MPO degranulation

MPO is an important indicator of polymorphonuclear leukocytes activation. It is released from azurophil granules of activated neutrophils. We evaluated the effect of SAAE on MPO degranulation. Results show that SAAE had no effect on MPO degranulation in resting neutrophils (Figure 5(A)) and also in neutrophils stimulated with PMA (Figure 5(B)).

Figure 5.

Effect of SAAE on MPO degranulation. Isolated human neutrophils (5 × 105) were incubated in the presence or absence of different SAAE concentrations in resting conditions (A), and stimulated with PMA (100 ng/mL) (B). MPO dégranulation was detected using western blot, MPO bands were quantified and expressed as % of control (mean ± SEM of three experiments, *p < 0.05).

Effect of SAAE on BALF protein content and cellularity in LPS-treated mice

IT administration of 5 µg of LPS to mice induced a significant increase in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) protein content after 24 h, compared with animals treated with either the vehicle or SAAE alone (Figure 6). The BALF protein content after IT LPS challenge was significantly lower when animals were pretreated with 200 mg/kg SAAE (Figure 6). IT LPS administration also induced a significant increase in both the BALF total cell count (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle or SAAE alone; Figure 7(A)) and the BALF neutrophil count after 24 h (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle or SAAE alone; Figure 7(B,C)). Neither the vehicle nor SAAE at 200 mg/kg modified the BALF cell count. However, intra-peritoneal SAAE injection at 200 mg/kg significantly reduced the BALF total cell count after IT administration of LPS (p < 0.05 vs. LPS alone). Simultaneous administration of LPS and SAAE significantly reduced neutrophils recruitment compared to LPS alone (p < 0.05 vs. LPS; Figure 7(B,C)).

Figure 6.

Effect of SAAE on the protein concentration of mouse bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Protein was measured in BALF 24 h after intra-tracheal instillation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS 5 µg/mouse) or in controls. LPS induced a massive increase in the protein content, which was significantly attenuated by SAAE (200 mg/kg) (n = 8, mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effect of SAAE on BALF cell content. BALB/c mice were treated with vehicle (NaCl 0.9%), SAAE (200 mg/kg), LPS (5 µg/mouse) or SAAE (200 mg/kg) plus LPS (5 µg/mouse), and cells were counted in BALF. (A), Total cell counts; (B) and (C), Neutrophils counts (n = 8, mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05).

SAAE inhibits MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity in lung tissues

To investigate the effect of SAAE on matrix metalloproteases (MMP-2, MMP-9) activity, the technique of zymography was used. Results (Figure 8) showed that the activity of these enzymes increased following LPS IT instillation compared to animals treated either with saline or SAAE alone. However, this increase was suppressed when mice were pretreated with 200 mg/kg of SAAE. A decrease of both MMP-2 (Figure 8(A)) and MMP-9 (Figure 8(B)) activities, 15% and 18%, respectively, were observed. However, neither the saline or SAAE at 200 mg/kg modified the MMPs activity in lung homogenate.

Figure 8.

Effect of SAAE on MMP-2 (A) and MMP-9 (B) activities in lung homogenates. BALB/c mice were treated with vehicle (NaCl 0.9%), SAAE (200 mg/kg), LPS (5 µg/mouse) or SAAE (200 mg/kg) plus LPS (5 µg/mouse), lungs were homogenate and centrifuged. MMPs activity was detected in supernatants using Gelatin zymography technique. Results were expressed as a percentage relative to control (n = 8, mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05).

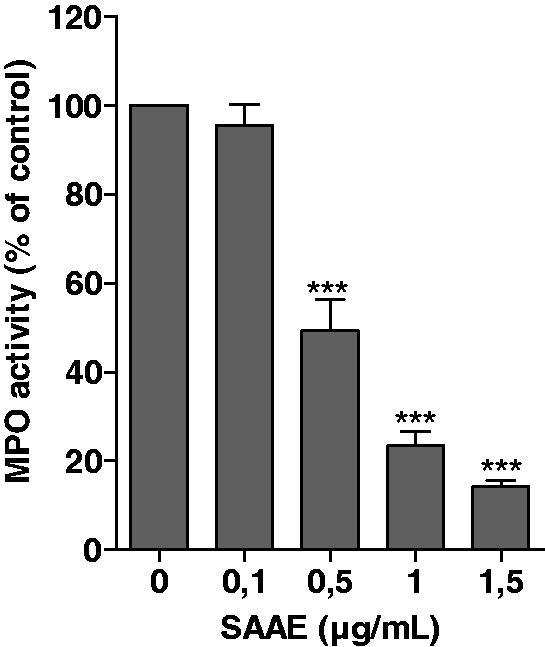

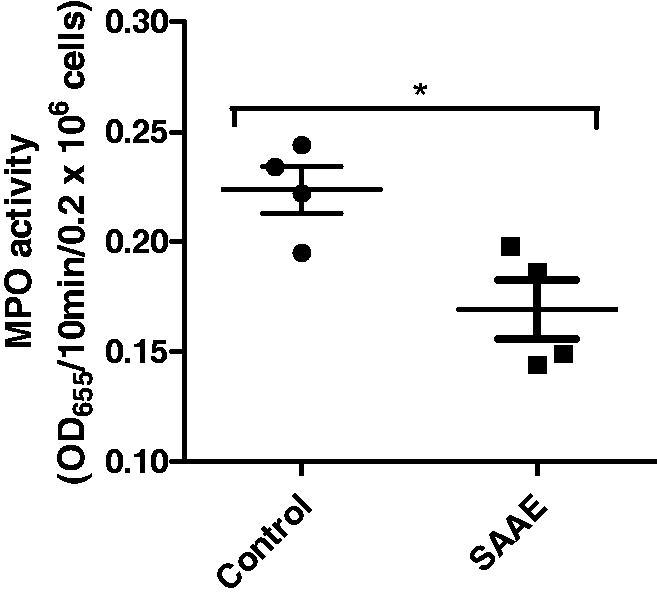

SAAE inhibits MPO activity in vivo

Treatment of animals with 200 mg/kg of SAAE decreased significantly the activity of MPO, in vivo, as compared to control group (p < 0.05). Figure 9 showed that the extract inhibited about 25% of the enzyme activity.

Figure 9.

Effect of SAAE on MPO activity in vivo. Mice were treated with vehicle (NaCl 0.9%) or SAAE (200 mg/kg), after 24 h, MPO activity was measured in circulating neutrophils using tetra-methylbenzidine oxidation at 655 nm (mean ± SEM of n = 4, *p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we show that SAAE inhibits ROS-dependent luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in resting, fMLF and PMA stimulated neutrophils. However, SAAE had no direct effect on superoxide anion or H2O2 levels but markedly inhibited MPO activity. In addition, SAAE attenuated LPS-induced lung inflammation in mice and reduces the activity of MMP-2 and -9.

SAAE inhibited luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in human neutrophils stimulated with the chemotactic peptide fMLF or the protein kinase C activator PMA. As fMLF and PMA induce NADPH oxidase activation through different transduction pathways, these results suggest that SAAE does not affect a specific transduction pathway but directly inhibits a final common biochemical target such as NADPH oxidase or MPO, or that it scavenges ROS. Our results showed that SAAE had no effect on cytochrome c reduction, a specific technique for superoxide anion detection, suggesting that SAAE does not affect NADPH oxidase activity or scavenge superoxide anions.

Luminol-amplified chemiluminescence can be used to assay both released and retained neutrophils ROS, as luminol is a membrane-permeable molecule. Luminol-amplified chemiluminescence is dependent on H2O2 and on peroxidases such as cytosolic peroxidases and MPO (Dahlgren and Karlsson 1999). To determine whether SAAE reacts with H2O2, we used a more specific technique to detect H2O2 in intact cells, based on DCFH oxidation. SAAE did not affect the amount of H2O2, suggesting that SAAE does not react with intracellular H2O2. However, SAAE inhibited MPO activity in vitro and exerted a potent anti-inflammatory effect in the lungs of mice exposed to LPS, reducing the BALF protein content, total cell number and neutrophil count.

BALF from mice exposed to LPS contained a large amount of protein, reflecting high-permeability pulmonary edema. The BALF protein concentration was significantly reduced by SAAE treatment, suggesting that SAAE reduces lung vascular permeability and edema, and might, therefore, protect the integrity of the alveolocapillary membrane. The reduction in neutrophils infiltration could explain these beneficial effects, as neutrophils are considered as primary cellular effector of alveolocapillary damage in COPD and asthma (Pesci et al. 1998, Fabbri et al. 2003).

Expression and activity of various MMPs have been reported in pathological conditions, such as COPD, emphysema, allergic lung inflammation and arthritis, but they are also implicated in cancer. They regulate recruitment, influx and transmigration of inflammatory cells from vasculature to the site of inflammation in tissue (Fanjul-Fernández et al. 2010). MMPs regulate the availability and activity of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines and they are implicated in creating chemokine gradients in tissue to recruit inflammatory cells to the site of injury or inflammation and can also regulate survival of inflammatory cells (Butler and Overall 2013). In this work, we found that SAAE exhibited an inhibitory effect against MMP-2 and -9, two metalloproteases known with their involvement in chronic lung inflammatory diseases.

Using allergic lung inflammation model, Corry et al. (2004), reported a reduction in the influx of inflammatory cells to the alveolar space in MMP-9-null mice. In the same model, the role of MMP-2 in leukocyte migration to the inflammation site was also demonstrated (Corry et al. 2002, 2004). In fact, MMP-9 exhibited more potent effect on inflammation than MMP-2 since various chemokines are affected by lack of MMP-9 resulting in disturbed influx of both neutrophils and eosinophils (Corry et al. 2004). MMP-9 plays an important role in reepithelization in tissue repair in the lung. Activated neutrophils released MMP-9 which cleaves and inactivates the serine protease inhibitor α1-antitrypsin known for its potent inhibition of neutrophil elastase. Thus, MMP-9 can this way indirectly promote the activity of neutrophil elastase also implicated in lung injury.

A previous in vitro study (Nam and Kim 2013) reported that eugenol the most representative compound of clove exhibited antioxidant activity and inhibits MMP-9 related to metastasis in human fibrosarcoma cells. This team showed that eugenol at 50 µM exhibited about 20% of inhibitory effect on MMP-9 activation in HT1080 cells compared to with PMA treatment group. Our results are consistent with these finding. In fact, the activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the lungs of animals pretreated with SAAE and challenged with LPS were significantly decreased to 15% and 18%, respectively. However, neither the saline nor SAAE at 200 mg/kg modified the MMPs activity.

MPO, an enzyme generating chlorinated oxidants, is not only implicated in antimicrobial defence but also in activating MMP, through the formation of ROS, playing an important role in the activation and induction of inflammation (Robert et al. 2016). MPO activity likely reflects an inflammatory infiltrate consisting partly of neutrophils, and neutrophil-derived elastase but also activating some chemokine (Meijer et al. 2007). The activation of MMP-9 potentiates pro-inflammatory interleukin-8 (Van den Steen et al. 2000) and processes IL-1β into an active form (Schonbeck et al. 1998). MPO stimulates murine peritoneal macrophages to produce ROS (Lincoln et al. 1995; Gelderman et al. 1998). Secreted ROS is known to enhance the secretion of alveolar macrophage-derived TNFα and IL-8, potent proinflammatory cytokines involved in recruitment of PMN to sites of inflammation (Nelson and Summer 1998; Gibson et al. 2001). Our results show that SAAE inhibited MPO activity in vitro and in vivo. Also, it reduced MMP-2 and -9 activities in lung homogenate, an effect possibly explaining the anti-inflammatory action observed in vivo.

Fruits, vegetables and spices, such as clove, oregano, mint, thyme and cinnamon, are important sources of antioxidants, including ascorbic acid, carotenoids, flavonoids and hydrolyzable tannins. Epidemiological studies indicate that populations that consume products rich in specific polyphenols have a lower incidence of inflammatory disorders such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, as well as certain cancers (Huxley and Neil 2003; Temple and Gladwin 2003). Clove represents one of the major vegetal sources of phenolic compounds as flavonoids, hidroxibenzoic acids, hidroxicinamic acids and hidroxiphenylpropens. With regard to the phenolic acids, eugenol is the main bioactive compound of clove is found in higher concentration (Shan et al. 2005). Roughly, 89% of the clove essential oil is eugenol and 5–15% is eugenol acetate and β-cariofileno (Jirovetz et al. 2006). Other phenolic acids found in clove are the caffeic, ferulic, elagic and salicylic acids but also some flavonoids such as kaempferol, quercetin and its derivates.

Thus, the beneficial effects of cloves are attributed to phenolic compounds including phenolic acids (gallic acid), flavonolglucosides, phenolic volatile oils (eugenol, acetyl eugenol) and tannins (Cortés-Rojas et al. 2014). These compounds scavenge free radicals and inhibit lipid oxidation in vitro (Gil et al. 2000; Noda et al. 2002). A comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD and ORAC assays showed that clove and plants as pine, cinnamon and mate proved its enormous potential as food preservative among the 30 plants analyzed (Dudonne et al. 2009). Further studies are needed to identify the precise compounds responsible for the MPO and MMP-2 and -9 activities inhibition observed in this work.

Conclusions

In conclusion, SAAE inhibited neutrophil luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in vitro, by inhibiting MPO. SAAE attenuated inflammation induced by IT endotoxin instillation in mice, leading to a decrease in the BALF protein concentration, total cellularity and neutrophils content but it also inhibits MMP-2 and -9, two metalloproteinases involved in many inflammatory and destructive tissue diseases.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad T, Shinkafi TS, Routray I, Mahmood A, Ali S. 2012. Aqueous extract of dried flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum inhibits inflammation and oxidative stress. J Basic Clin Pharm. 3:323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior BM. 1984. Oxidants from phagocytes: agents of defense and destruction. Blood. 64:959–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior BM. 2000. Phagocytes and oxidative stress. Am J Med. 109:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Panda CK, Das S. 2006. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum L.), a potential chemopreventive agent for lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 27:1645–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. 2009. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory diseases. Lancet. 373:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler GS, Overall CM. 2013. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of signaling molecules to regulate inflammation. Periodontol 2000. 63:123–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo DD, Gueders MM, Rocks N, Sounni NE, Evrard B, Bartsch P, Louis R, Noel A, Foidart JM. 2003. Pathogenic role of matrix metalloproteases and their inhibitors in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and therapeutic relevance of matrix metalloproteases inhibitors. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand). 49:875–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Di Sabatino A, Bauer M, Della Riccia DN, Bizzini F, Biagi F, Cifone MG, Corazza GR, Schuppan D. 2005. Matrix metalloproteinase pattern in celiac duodenal mucosa. Lab Invest. 85:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry DB, Rishi K, Kanellis J, Kiss A, Song LZ, Xu J, Feng Z, Werb L, Kheradmand F. 2002. Decreased allergic lung inflammatory cell egression and increased susceptibility to asphyxiation in MMP2-deficiency. Nat Immunol. 3:347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry DB, Kiss A, Song LZ, Song L, Xu J, Lee SH, Werb Z, Kheradmand F. 2004. Overlapping and independent contributions of MMP2 and MMP9 to lung allergic inflammatory cell egression through decreased CC chemokines. FASEB J. 18:995–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Rojas DF, De Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. 2014. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 4:90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. 1999. Respiratory burst in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Meth. 232:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudonne S, Vitrac X, Coutiere P, Woillez M, Merillon JM. 2009. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J Agric Food Chem. 57:1768–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Benna J, Dang PM, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Elbim C. 2005. Phagocyte NADPH oxidase: a multicomponent enzyme essential for host defenses. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 53:199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Benna J, Dang PM. 2007. Analysis of protein phosphorylation in human neutrophils. Methods Mol Biol. 412:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri LM, Romagnoli M, Corbetta L, Casoni G, Busljetic K, Turato G, Ligabue G, Ciaccia A, Saetta M, Papi A. 2003. Differences in airway inflammation in patients with fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 167:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR. 2001. The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery. Environ Health Perspect. 109:69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanjul-Fernandez M, Folgueras AR, Cabrera S, Lopez OC. 2010. Matrix metalloproteinases: evolution, gene regulation and functional analysis in mouse models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1803:3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelderman MP, Lefkowitz DL, Lefkowitz SS, Bollen A, Moguilevsky N. 1998. Exposure of macrophages to an enzymatically inactive macrophage mannose receptor ligand augments killing of Candida albicans. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 217:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson PG, Simpson JL, Saltos N. 2001. Heterogeneity of airway inflammation in persistent asthma: evidence of neutrophilic inflammation and increased sputum interleukin-8. Chest. 119:1329–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MI, Tomas-Barberan FA, Hess-Pierce B, Holcroft DM, Kader AA. 2000. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. J Agric Food Chem. 48:4581–4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamini-Kadar N, Hamdane F, Boutoutaou R, Kihal M, Henni JE. 2014. Antifungal activity of clove (Syzygium aromaticum L.) essential oil against phytopathogenic fungi of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in Algeria. JEBAS. 2:447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. 1998. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood. 92:3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein G, Miyashiro H, Nakamura N, Hattori M, Kakiuchi N, Shimotohno K. 2000. Inhibitory effects of Sudanese medicinal plant extracts on hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease. Phytother Res . 14:510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley RR, Neil H. 2003. The relation between dietary flavonol intake and coronary heart disease mortality: a metaanalysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 57:904–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirovetz L, Buchbauer G, Stoilova I, Stoyanova A, Krastanov A, Schmidt E. 2006. Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of clove leaf essential oil. J Agric Food Chem. 54:6303–6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff SJ. 2005. Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J Leukoc Biol. 77:598–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PS, Febriyanti RM, Sofyan FF, Luftimas DE, Abdulah R. 2014. Anticancer potential of Syzygium aromaticum L. in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell lines. Pharmacognosy Res. 6:350–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KG, Shibamoto T. 2001. Antioxidant property of aroma extract isolated from clove buds [Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. et Perry]. Food Chem. 74:443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln JA, Lefkowitz DL, Cain T, Castro A, Mills KC, Lefkowitz SS, Moguilevsky N, Bollen A. 1995. Exogenous myeloperoxidase enhances bacterial phagocytosis and intracellular killing by macrophages. Infect Immun. 63:3042–3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer MJW, Mieremet-Ooms MAC, van der Zon AM, van Duijn W, van Hogezand RA, Sier CFM, Hommes DW, Lamers CBHW, Verspaget HW. 2007. Increased mucosal matrix metalloproteinase-1, -2, -3 and -9 activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and the relation with Crohn’s disease phenotype. Dig Liver Dis. 39:733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milind P, Deepa K. 2011. Clove: a champion spice. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Minihane AM, Vinoy S, Russell WR, Baka A, Roche HM, Tuohy KM, Teeling JL, Blaak EE, Fenech M, Vauzour D. 2015. Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. Br J Nutr. 114:999–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam H, Kim MM. 2013. Eugenol with antioxidant activity inhibits MMP-9 related to metastasis in human fibrosarcoma cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 55:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S, Summer WR. 1998. Innate immunity, cytokines, and pulmonary host defense. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 12:555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Kaneyuki T, Mori A, Packer L. 2002. Antioxidant activities of pomegranate fruit extract and its anthocyanidins: delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin. J Agric Food Chem. 50:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez L, Aquino MD. 2012. Microbicide activity of clove essential oil (Eugenia caryophyllata). Braz J Microbiol. 43:1255–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesci A, Balbi B, Majori M, Cacciani G, Bertacco S, Alciato P, Donner CF. 1998. Inflammatory cells and mediators in bronchial lavage of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 12:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punchard NA, Whelan CJ, Adcock I. 2004. Editorial: The journal of inflammation. J Inflamm. 1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert MC, Arafat SN, Spurr-Michaud S, Chodosh J, Dohlman CH, Gipson IK. 2016. Tear matrix metalloproteinases and myeloperoxidase levels in patients with boston keratoprosthesis type I. Cornea. 35:1008–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonbeck U, Mach F, Libby P. 1998. Generation of biologically active IL-1 beta by matrix metalloproteinases: a novel caspase-1-independent pathway of IL-1 beta processing. J Immunol. 161:3340–3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B, Cai YZ, Sun M, Corke H. 2005. Antioxidant capacity of 26 spice extracts and characterization of their phenolic constituents. J Agric Food Chem. 53:7749–7759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple NJ, Gladwin KK. 2003. Fruit, vegetables, and the prevention of cancer: research challenges. Nutrition. 19:467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Steen PE, Proost P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. 2000. Neutrophil gelatinase B potentiates interleukin-8 tenfold by amino terminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alphaand leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood. 96:2673–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udby L, Borregaard N. 2007. Subcellular fractionation of human neutrophils and analysis of subcellular markers. Methods Mol Biol. 412:35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zore GB, Thakre AD, Jadhav S, Karuppayil SM. 2011. Terpenoids inhibit Candida albicans growth by affecting membrane integrity and arrest of cell cycle. Phytomedicine. 18:1181–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]