Abstract

Objectives. To quantify the effect of the upsurge of violence on life expectancy and life span inequality in Mexico after 2005.

Methods. We calculated age- and cause-specific contributions to changes in life expectancy and life span inequality conditional on surviving to age 15 years between 1995 and 2015. We analyzed homicides, medically amenable conditions, diabetes, ischemic heart diseases, and traffic accidents by state and sex.

Results. Male life expectancy at age 15 years increased by more than twice in 1995 to 2005 (1.17 years) than in 2005 to 2015 (0.55 years). Life span inequality decreased by more than half a year for males in 1995 to 2005, whereas in 2005 to 2015 the reduction was about 4 times smaller. Homicides for those aged between 15 and 49 years had the largest effect in slowing down male life expectancy and life span inequality. Between 2005 and 2015, three states in the north experienced life expectancy losses while 5 states experienced increased life span inequality.

Conclusions. Ten years into the upsurge of violence, Mexico has not been able to reduce the homicide levels to those before 2005. Life expectancy and life span inequality stagnated since 2005 for young men at the national level. In some states, males live shorter lives than in 2005, on average, and experience higher uncertainty in their eventual death.

Violence has become a major public health issue in Latin America.1 This region experiences the highest homicide rate in the world (more than 16.3 per 100 000 people), with some countries in Central America undergoing a recent upsurge in homicides.2 In Mexico, homicide rates declined from 1995 to 2006, but these trends were reversed and homicides more than doubled between 2007 and 2012 (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). This increase has been associated with more enforcement operations trying to mitigate drug cartel activities, increased territorial competition, and higher profitability in the drug-trade flow with the United States.3–5 This led to a cycle of violence—the so-called War on Drugs—and the spillover onto civilians,6 which, along with an increasing burden of diabetes, led to stagnating male life expectancy in the period 2000 to 2010.7 At the subnational level, gains in life expectancy attributable to medically amenable causes, such as infectious diseases, respiratory diseases, and birth conditions, were wiped out by the increase of homicides after 2005 in each of the 32 states in Mexico, with large regional variation.8

Trends in life expectancy are important and have been studied in Mexico and its states.7–9 However, life expectancy masks inequality of life spans or life span variation.10 Variability in age at death (life span) is important because it addresses the growing interest in health inequalities11 and because larger variation in life spans implies greater uncertainty in the timing of death at the individual level and has implications for the planning of life’s events.12,13 From a public health perspective, larger life span variation implies increasing vulnerability at the societal level, which suggests ineffectiveness of policies aiming to protect individuals against life’s vicissitudes.12 In the context of rising violence, it implies a failure of social protection policies aiming at decreasing homicide and crime rates and increasing vulnerability at the population level. Previous studies have found a negative association between life expectancy and life span variation, suggesting that as life expectancy increases, inequality in life spans decreases.12,14 However, at the subnational level and during periods of life expectancy fluctuation, increases in life span variation may simultaneously occur with increases in life expectancy, mostly attributable to a slowdown in mortality improvements over ages 20 to 65 years.13,15 This is particularly relevant for countries that have experienced an upsurge in homicides because this increase has mainly affected young individuals.

In Mexico, homicides are concentrated between ages 15 and 50 years, affecting mainly males.8 It is unclear what their net effect is on life span inequality, but they certainly had an effect on premature mortality. We thus hypothesize that Mexican males may be experiencing increases in life span inequality in tandem with declines in life expectancy. We also expect uneven variability across states in the country attributable to the changing dynamics of violence and homicides in Mexico.16 For instance, states in the northern part of Mexico (e.g., Chihuahua, Durango, and Sinaloa) experienced the largest losses in life expectancy between 2005 and 2010,8 and it is likely they also exhibited large life span variation during that period, although this impact may now be larger in other states as homicides spread throughout the country in recent years.17 On the other hand, medically amenable mortality improvements, which have been Mexico’s priority since the 1990s,18 could have had a substantial effect on reducing variation in life spans, particularly in the poorer states, which are mostly concentrated in the south.

This article makes 3 main contributions. First, it contributes to the literature on life span variation and inequalities in health in the context of rising homicides. Most literature in this area focuses on the social determinants of health such as socioeconomic status or educational attainment as proximate determinants of life span variation and health inequality.12,13 Our article highlights the role of violence, and its ultimate consequence in the form of homicides, among young adults, on increasing life span inequality. We describe the observed changes in homicide mortality and their link with life span variation and life expectancy by sex and by region in Mexico. A second contribution is its focus on Mexico with the growing violence associated with the War on Drugs making it a serious health policy concern.7,8 Understanding the consequences of violence on population health is important for policymakers in Mexico and other countries experiencing similar increases in homicides such as Honduras in Central America and Venezuela in South America.2 Finally, this analysis contributes to our knowledge of regional inequality in life spans.

We analyzed how life expectancy and life span inequality for the young population changed over the period from 1990 to 2015 for females and males in Mexico. This framework allows us to thoroughly analyze premature mortality and to determine the ages and causes of death that contributed the most to the observed changes.

METHODS

We used data on deaths from vital statistics files available through the Mexican Institute of Statistics19 that includes information on cause of death by age, sex, and place of occurrence from 1995 to 2015. In addition, we used population estimates corrected for completeness, age misstatement, and international migration from the Mexican Population Council to construct age-specific death rates by age, sex, and state.20

Cause-of-Death Classification

We classified deaths into 8 categories representing the main causes of death in Mexico by using the concept of “amenable/avoidable” mortality (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).21,22 This concept assumes that some conditions should not cause death in the presence of timely and effective medical care and is used as a proxy for the performance of health care systems.21 To mitigate biases attributable to misclassification of causes of death, we focused on deaths occurring before age 85 years as cause-specific coding practices for older ages are less reliable because of the presence of comorbidities,23 and about 99% of homicides occurred at younger ages in the study period.

We studied 2 comparable 10-year periods—from 1995 to 2005, and from 2005 to 2015—that represent periods of major changes in homicides (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The first period corresponds to mortality improvements (1995–2005) in which life expectancy increased by 2.1 and 4.3 years for males and females, respectively,20 and homicide rates declined among young adults,19 and the second period (2005–2015) was characterized by the upsurge of violence and homicides in Mexico.8

Life Span Inequality Indicator

We used “years of life lost” as a dispersion indicator and refer to it as “life span inequality” or “life span variation” from age 15 years. It is defined as the average remaining life expectancy at death, or life years lost because of death (see summary, section A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).14 For example, if a cohort of newborns all die at the same age, then the value of life span inequality is zero; to the extent that death occurs at different ages, those who die “prematurely” will contribute years to life span variation. We condition on surviving to age 15 years because more than 95% of homicides occur at that age and older and because including infant mortality conceals dynamics of mortality at adult ages.10

This indicator is easy to understand, to interpret, and to decompose thereby allowing us to quantify the impact of age- and cause-specific mortality on changes in life span variation over time.14 Moreover, the high correlation between our preferred indicator and other measures of variability in life spans (e.g., variance, Gini coefficient) suggests that our main results would be consistent with those obtained with any of these additional measures.14

Demographic Methods

To mitigate random variation in cause-of-death classification, we smoothed cause-specific death rates over age by using a 1-dimension P-spline separately by year, sex, and state, and rescaled them to all-cause death rates to maintain the overall mortality level.24 Using these mortality rates, we computed period life tables for each year (1995–2015), state, and sex following standard demographic methods.25 Finally, we computed life expectancies and life span variation conditioned on surviving to age 15 years and estimated the age- and cause-specific contributions to yearly differences between the study periods by using standard decomposition techniques (see section B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).26 All analyses were carried out by using R27 and are reproducible (see section C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org; in addition, we created an interactive app to perform sensitivity analyses available here: https://demographs.shinyapps.io/LVMx_15_App).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows cause-specific contributions to changes in life expectancy and life span inequality at age 15 years between 1995 and 2015 and between 2005 and 2015. Among males, life expectancy increased more than twice as fast in 1995 to 2005 (1.17 years) than in 2005 to 2015 (0.55 years). Most causes of death contributed to life expectancy’s improvement in 1995 to 2005 (except for diabetes and accidents). Importantly, homicides declined in 1995 to 2005, which accounted for about 38.5% (0.45 years) of the overall gain in life expectancy in this period. About 80% (0.36 years) of the homicide reduction was concentrated between the ages of 15 and 49 years (Figure B, panel a, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). By contrast, the slowed-down improvement in life expectancy in 2005 to 2015 was mainly the result of rising homicides and heart diseases—hence, their negative contributions. Female life expectancy increased by 0.58 years in 1995 to 2005 and 0.57 years in 2005 to 2015. These gains resulted from mortality improvements in most causes of death with a negative impact of diabetes and a negligible impact of homicides, traffic accidents, and heart diseases.

TABLE 1—

Contribution to the Change in Life Expectancy and Life Span Inequality at Age 15 Years in the Periods 1995–2005 and 2005–2015 at the National Level by Cause of Death When Younger Than 85 Years: Mexico

| Contribution to Life Expectancy, Years |

Contribution to Life Span Inequality, Years |

|||

| Cause of Death | 1995–2005 | 2005–2015 | 1995–2005 | 2005–2015 |

| Males | ||||

| Amenable to medical service | 0.508 | 0.169 | −0.073 | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | −0.572 | −0.076 | 0.028 | −0.029 |

| IHD | 0.007 | −0.116 | −0.023 | 0.003 |

| Lung cancer | 0.048 | 0.099 | −0.004 | −0.003 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.041 | 0.280 | −0.026 | −0.105 |

| Homicide | 0.447 | −0.290 | −0.265 | 0.186 |

| Traffic accidents | −0.069 | 0.180 | 0.048 | −0.097 |

| Other | 0.767 | 0.303 | −0.193 | −0.107 |

| Total change | 1.17 (57.08 to 58.25) | 0.55 (58.25 to 58.80) | −0.54 (14.31 to 13.77) | −0.15 (13.77 to 13.62) |

| Females | ||||

| Amenable to medical service | 0.630 | 0.393 | −0.236 | −0.144 |

| Diabetes | −0.612 | 0.106 | 0.100 | −0.060 |

| IHD | 0.074 | −0.048 | −0.023 | −0.012 |

| Lung cancer | 0.017 | 0.021 | −0.005 | −0.002 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.032 | 0.060 | −0.017 | −0.028 |

| Homicide | 0.023 | −0.039 | −0.014 | 0.029 |

| Traffic accidents | −0.021 | 0.044 | 0.015 | −0.024 |

| Other | 0.443 | 0.030 | −0.156 | 0.030 |

| Total change | 0.58 (62.75 to 63.33) | 0.57 (63.33 to 63.90) | −0.34 (12.40 to 12.06) | −0.21 (12.06 to 11.85) |

Note. IHD = ischemic heart disease.

Life span inequality declined by more than half a year between 1995 (14.31) and 2005 (13.77) for males. This means that, on average, Mexican males were losing 6 months of life less at their time of death in 2005 than in 1995. Although life span inequality also declined between 2005 and 2015 (–0.15), the reduction in 1995 to 2005 was about 4 times larger. In other words, male life span inequality was stagnant in recent times. Nonetheless, improvements in other causes of death contributed to a reduction in life span inequality in both periods; for example, mortality declines in accidents and cirrhosis at younger ages (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Importantly, homicides (about 0.19 years) had the largest effect on increasing life span variation in 2005 to 2015 (i.e., positive contribution). For females, life span variation decreased since 1995 because of improvements in most causes of death. However, in 1995 to 2005, increased mortality from diabetes and traffic accidents increased life span inequality, and in 2005 to 2015, homicides were the major contributor to slowing down improvements in variation of life spans. These results underscore the major role of rising homicide rates among young adults in recent times and the consequent slow improvement in reducing life span inequality.

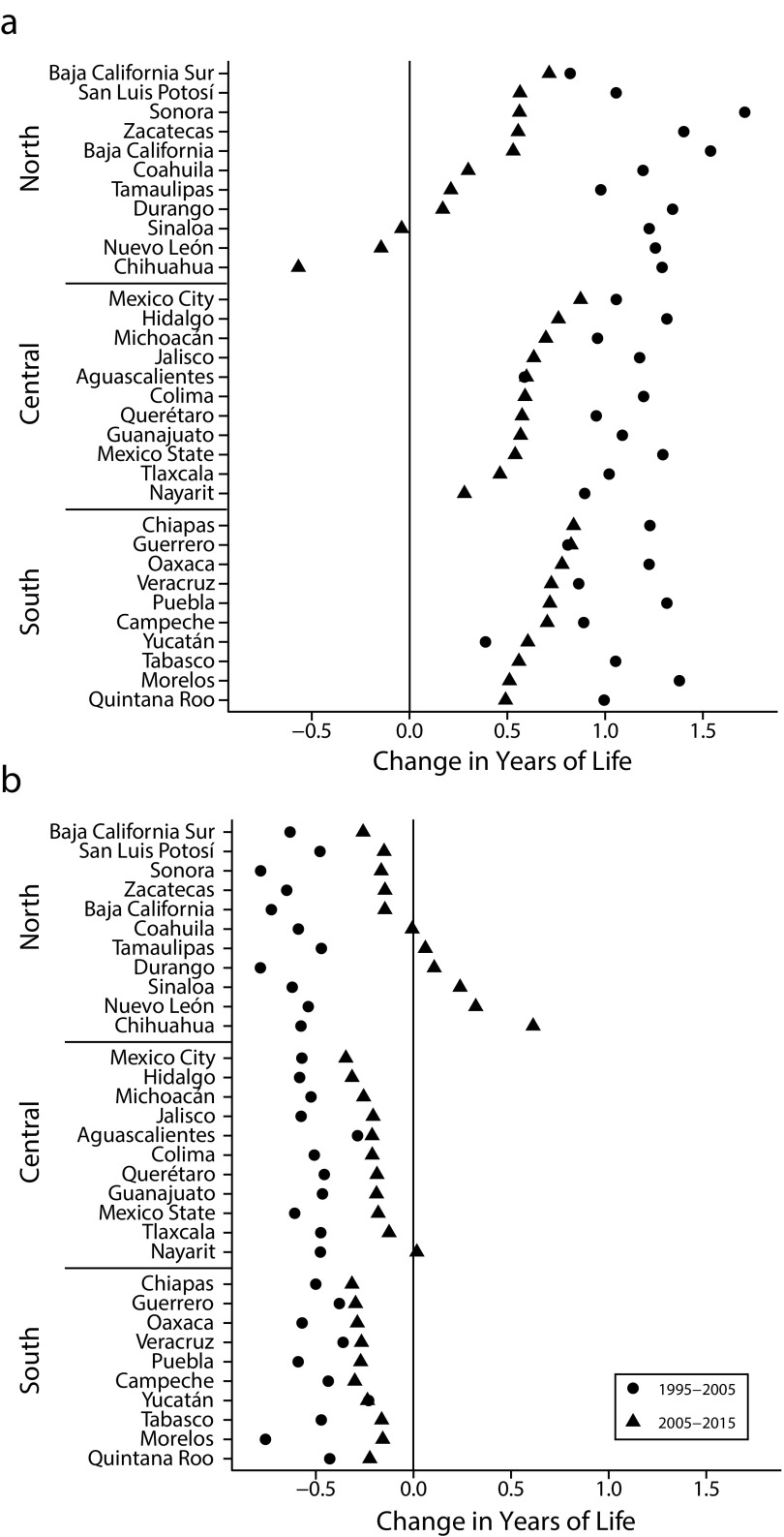

In Figures 1 and 2, we focus on results for males because the impact of homicides is larger among them; results for females are in Figures C and D (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Figure 1 shows changes in life expectancy (panel a) and in life span inequality (panel b) for males in each of the 32 states in Mexico between 1995 and 2005 and between 2005 and 2015. We grouped states into 3 broad regions: north, central, and south.

FIGURE 1—

Changes by State and Period in (a) Male Life Expectancy at Age 15 Years and (b) Male Life Span Inequality at Age 15 Years: Mexico, 1995–2005 and 2005–2015

Note. Life span inequality refers to life years lost because of death, which indicates heterogeneity in ages at death. A value of zero in life span inequality indicates that all cohort members die at the same age (i.e., no inequality in ages at death). This figure shows how life span inequality changed in 2 periods: positive values suggest increases in years of life lost and negative values correspond to reductions in life years lost because of death. Hence, the desirable association would be that, as life expectancy increases, life span inequality decreases. This figure shows each of the 32 Mexican states grouped in broad regions: north, central, and south. Within each region, states are ordered according to the magnitude in changes in life expectancy at age 15 years in the period 2005–2015.

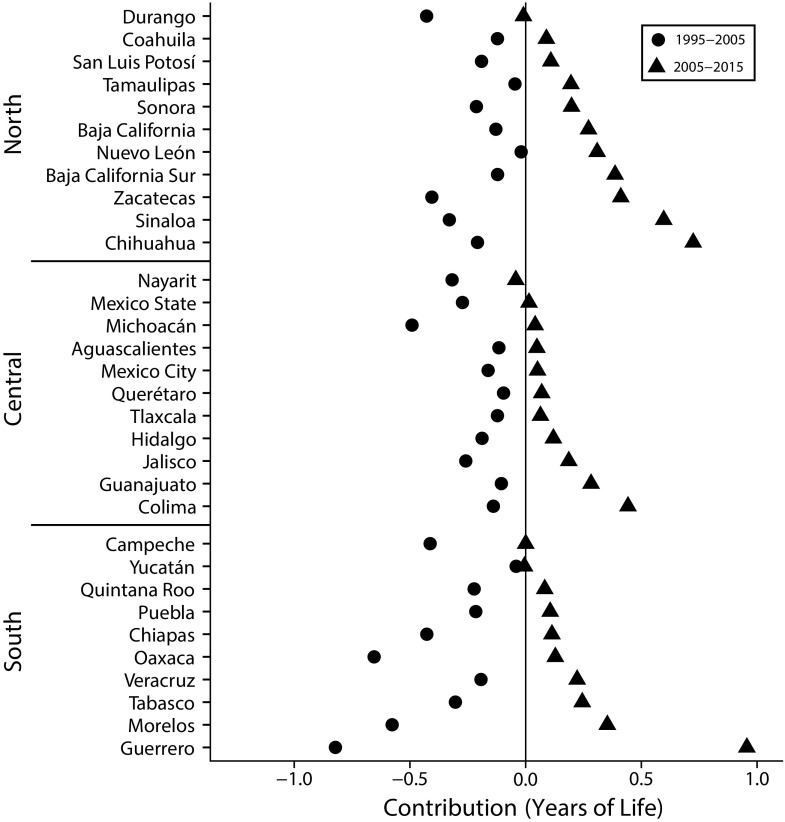

FIGURE 2—

Contribution of Homicide Mortality to Changes in Male Life Span Inequality by State and Period: Mexico, 1995–2005 and 2005–2015

Note. This figure shows how homicides contributed to changes in life span inequality (i.e., panel b of Figure 1) in 2 periods: positive values suggest increases in years of life lost because of homicides and negative values correspond to reductions in life years lost because of death. This figure shows each of the 32 Mexican states grouped in broad regions: north, central, and south. Within each region, states are ordered according to the magnitude of the impact of homicides to life span inequality at age 15 years in the period 2005 to 2015.

Life expectancy among males had a larger increase in 1995 to 2005 than in 2005 to 2015 across all states (panel a) except for Yucatán; some states even experienced reductions in life expectancy in 2005 to 2015, particularly in the north (e.g., Chihuahua, Nuevo León, and Sinaloa). Life span inequality (panel b) was reduced in most states over the 2 decades, 1995 to 2015, except for those in the north and Nayarit. For example, almost every state between 1995 and 2005 had major reductions in life span inequality of at least 0.4 years, but between 2005 and 2015, all states in the north had negligible reductions in life span inequality with 5 states having a large increase (Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas [all bordering Texas in the United States], Sinaloa, and Durango).

Figure 2 shows the contribution of homicides to changes in life span inequality between 1995 and 2005 and between 2005 and 2015 by state. For contributions from all cause-of-death categories and for females, see Figures E and F (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Every state experienced decreased life span inequality because of reductions in homicide mortality between 1995 and 2005. In the same period, all but 2 states for males, Baja California Sur in the north and Tlaxcala in the central region, showed decreased life span variation attributed to improvements in medically amenable conditions (Figures E and F). As we hypothesized, the states showing the larger reductions were mostly concentrated in the southern region of Mexico (e.g., Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero, and Morelos).

A decade later (2005–2015), however, there was more heterogeneity in the contribution of causes of death to life span inequality. For example, conditions amenable to medical service contributed to reductions in life span inequality in some states but small increases in 9 states for males distributed across the country, while cirrhosis decreased variation in life spans in the central and northern regions. Homicides increased variation in life spans. Although the increase in homicides affected life span inequality in all states after 2005, 1 state in the south was affected the most (about a 1-year increase for males and about 2 months for females in Guerrero), followed by some states in the north (increase of about 0.75 and 0.5 years in Chihuahua and Sinaloa, respectively) and in the central part of the country (e.g., Colima). Mortality associated with diabetes showed negligible contributions to life span inequality in both periods. Results for females indicate substantial reductions in life span inequality from medically amenable conditions and diabetes in the period 1995 to 2015.

DISCUSSION

Ten years after the beginning of the War on Drugs, Mexico has not been able to reduce homicides and their effect on longevity, at least to the levels observed back in 2005. As violence spread throughout the country,17 life expectancy gains slowed down between 2005 and 2015, with a temporary reversal in average life span in 2005 to 2010.7,8 Despite recent efforts from the Mexican government to contain the upsurge of violence in the country,5,28 data up to 2015 show that life circumstances among young adults have not improved and are actually deteriorating. For example, almost every state experienced a reduction in male life expectancy at age 15 years across all regions in Mexico because of homicides (Figure G, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The strongest effect occurred in Guerrero, a state in the southern region, where life expectancy was reduced by almost 2 years between 2005 and 2015, followed by Chihuahua and Sinaloa in the north, with life expectancy losses of 1 year each. Other states also experienced reductions in life expectancy albeit of lower magnitude; 3 states in the north (Zacatecas, Baja California Sur, and Nuevo León), 1 in the central region (Colima), and 1 in the south (Morelos) experienced losses of half a year. These detrimental consequences offset increases in life expectancy attributable to ongoing public health interventions such as the enactment of a universal health insurance program (Seguro Popular).8,9,18

Furthermore, homicides have slowed down the progress in reducing life span inequality among young adults in Mexico. Although life span inequality declined by more than half a year between 1995 and 2005, a decade later, this progress was stagnant and barely reached a reduction of less than 2 months. Increase in homicide mortality, concentrated in the young population (between the ages of 15 and 50 years), accounted for most of this outcome. Thus, males in Mexico not only live less on average, as shown by life expectancy, but they also face more uncertainty in their time of death attributable to the increase in homicides. Larger variation of life spans underlies greater vulnerability at the population level. For example, in Mexico, the expected years lived vulnerable to becoming victim of violence increased by 30.5 million person-years between 2005 and 2014.29 Moreover, increasing inequality of life spans means larger heterogeneity in population health, which translates into the need for more resources to optimize health over the life course.13

At the subnational level, the states that experienced reductions in life expectancy after 2005 also showed increases in life span inequality attributable to homicides. These results are consistent with the upsurge in violence in these parts of the country. Although homicides have spread across Mexico,16 they are not evenly shared among states and over time. By 2010, the north of Mexico was the region most affected by homicide mortality.8 By contrast, by 2015, all regions showed similar patterns of the effects of homicides on life span inequality. Moreover, although in 2010 Chihuahua (northern region) was the state affected the most by homicides relative to the 2005 level, in 2015, Guerrero (southern region) had overtaken this place.

The impact of violence in the population in these states is staggering. For instance, in 2010, males aged 15 to 50 years in Chihuahua had 3 times higher mortality than the US troops in Iraq between 2003 and 2006.8 Recent evidence suggests that the second- and fifth-most dangerous cities in the world are located in the state of Guerrero, ranked along with cities in countries with higher homicide rates than Mexico.30 As a result, young males in Guerrero experienced an increase in life span inequality of almost an additional year. These results complement previous evidence on adult health inequalities among states9,22 by identifying homicides as a direct contributor to inequalities in population health between and within states. Moreover, homicides are the ultimate form of violence, but they do not fully represent its burden on population health. As a social determinant of health, exposure to violence can increase the likelihood that young people will perpetrate gun violence31 and increases the risk of depression, alcohol abuse, suicidal behavior, and psychological problems, among other detrimental consequences over the life course.32 Even witnessing violence can affect the well-being of the population by increasing rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression.33

Here, we quantified the effect of rising homicides on longevity and on life span inequality. However, our understanding of the consequences of violence would benefit from future research examining if indeed individuals living in states with increases in life span inequality do perceive higher vulnerability and how this might affect their long-term decisions. These studies should also focus on women as they are less likely to experience a crime, but they perceive greater vulnerability.29 Moreover, often women are placed in caregiving roles for victims or experience the loss of close relatives because of violence that affects their lives and psychological well-being.29 In addition, more research is needed to quantify the long-lasting consequences of rising violence in the context of the War on Drugs to anticipate and intervene in the pathways through which the current violence might affect future health outcomes. For example, the health system might need to be prepared for mental health issues such as depression, suicidal behavior, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

In an international context, Mexico’s level of violence is not even the highest in the region. Countries in Central America, such as El Salvador and Honduras, and Venezuela, Colombia, and Brazil in South America have higher homicide rates.1,2 It is likely that these countries experience higher variation in life spans, which, along with the existence of high levels of homicides, points to possible failure of policies to reduce the burden of violence. These policies should pay more attention to social determinants of premature mortality and psychosocial factors and get to the root of violence to prevent its diffusion toward the young population.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, inaccuracies in cause-of-death practices are likely to be present in the data that we used.8 To reduce these inaccuracies, we used broad causes of death and adjusted them with a smoothing process over age to have reliable cause-of-death distributions.24 Second, our estimated effects of homicides could be a lower bound because of undercounting, underreporting, and the large number of missing individuals.8 Third, we were not able to disentangle whether a homicide was drug-related (e.g., a homicide resulting from altercations between drug cartels and army operations).Thus, our results provide an upper bound for the possible impact of the War on Drugs at the population level. Finally, we were not able to disaggregate deaths by socioeconomic status and other social factors that are closely linked with homicides given that the data are at the aggregate national level. Future research should try to shed light into the individual-level pathways of violence and its effects on life expectancy and life span inequality.31 This illustrates the need for reliable estimates of mortality by cause of death and population by socioeconomic status and other social factors in Mexico.

Conclusion

Mexico has failed to recognize and correct the detrimental consequences in health and human rights that suppressive and drug-prohibition policies have had on the population.34 There is an urgent need to replace current policies with policies that are less focused on military actions against drug cartels. For example, other countries that underwent a similar upsurge of violence associated with drug cartels successfully implemented programs on improving schooling outcomes and educational and community programs to reduce the risk factors of violence (e.g., alcohol consumption).35 This will prevent homicides and contribute significantly to increases in life expectancy as well as greater equality of individual life spans in Mexico.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

H. Beltrán-Sánchez acknowledges support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2C-HD041022) to the California Center for Population Research at UCLA. J. M. Aburto acknowledges support from University of Southern Denmark and the Lifespan Inequalities Group at Max-Planck Institute for Demographic Research, European Research Council grant 716323.

J. M. Aburto thanks Jim Vaupel for his support on doing research. Both authors are grateful to Jim Oeppen and Alyson van Raalte for comments on a previous version of the article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors have completed the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study involved secondary data analysis of public sources, which did not have any individual identifiers. As such, ethical approval for human participant research from the institutional review board of the respective institutions was exempted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briceño-León R, Villaveces A, Concha-Eastman A. Understanding the uneven distribution of the incidence of homicide in Latin America. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(4):751–757. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global study on homicide 2013: trends, contexts, data. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2013.

- 3.Castillo J, Mejía D, Restrepo P. Scarcity without Leviathan: the violent effects of cocaine supply shortages in the Mexican drug war. Center for Global Development Working Papers. 2014. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/scarcity-leviathan-effects-cocaine-supply-shortages_1.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 4.Dell M. Trafficking networks and the Mexican drug war. Am Econ Rev. 2015;105(6):1738–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ríos V. Why did Mexico become so violent? A self-reinforcing violent equilibrium caused by competition and enforcement. Trends Organ Crime. 2013;16(2):138–155. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinle K, Rodríguez Ferreira O, Shirk DA. Drug violence in Mexico: data and analysis through 2016. San Diego, CA: University of San Diego; 2017.

- 7.Canudas-Romo V, García-Guerrero VM, Echarri-Cánovas CJ. The stagnation of the Mexican male life expectancy in the first decade of the 21st century: the impact of homicides and diabetes mellitus. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(1):28–34. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aburto JM, Beltrán-Sánchez H, García-Guerrero VM, Canudas-Romo V. Homicides in Mexico reversed life expectancy gains for men and slowed them for women, 2000–10. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(1):88–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gómez-Dantés H, Fullman N, Lamadrid-Figueroa H et al. Dissonant health transition in the states of Mexico, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388(10058):2386–2402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31773-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards RD, Tuljapurkar S. Inequality in life spans and a new perspective on mortality convergence across industrialized countries. Popul Dev Rev. 2005;31(4):645–674. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmot M. Inequalities in health. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):134–136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Raalte AA, Kunst AE, Deboosere P et al. More variation in lifespan in lower educated groups: evidence from 10 European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(6):1703–1714. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasson I. Trends in life expectancy and lifespan variation by educational attainment: United States, 1990–2010. Demography. 2016;53(2):269–293. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0453-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaupel JW, Zhang Z, van Raalte AA. Life expectancy and disparity: an international comparison of life table data. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1):e000128. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aburto JM, van Raalte A. Lifespan dispersion in times of life expectancy fluctuation: the case of Central and Eastern Europe. Demography. 2018;55(6):2071–2096. doi: 10.1007/s13524-018-0729-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flores M, Villarreal A. Exploring the spatial diffusion of homicides in Mexican municipalities through exploratory spatial data analysis. Cityscape. 2015;17(1):35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinal-Enríquez J, Larralde H. Analysis of México’s Narco-War Network (2007–2011) PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González-Pier E, Barraza-Lloréns M, Beyeler N et al. Mexico’s path towards the Sustainable Development Goal for health: an assessment of the feasibility of reducing premature mortality by 40% by 2030. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(10):e714–e725. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografí. Micro-data files on mortality data 1995–2015. 2017. Available at: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/mortalidad. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 20. Consejo Nacional de Población. Population estimates. 2017. Available at: https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/proyecciones-de-la-poblacion-de-mexico-y-de-las-entidades-federativas-2016-2050. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 21.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(1):58–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aburto JM, Riffe T, Canudas-Romo V. Trends in avoidable mortality over the life course in Mexico, 1990–2015: a cross-sectional demographic analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e022350. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg HM. Cause of death as a contemporary problem. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1999;54(2):133–153. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/54.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camarda CG. MortalitySmooth: an R package for smoothing Poisson counts with P-splines. J Stat Softw. 2012;50(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston SH, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography. Measuring and Modeling Population Processes. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horiuchi S, Wilmoth JR, Pletcher SD. A decomposition method based on a model of continuous change. Demography. 2008;45(4):785–801. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Team R Core. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. Available at: https://www.r-project.org. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 28.Astorga L, Shirk DA. Drug trafficking organizations and counter-drug strategies in the US–Mexican context. 2010. Available at: https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt8j647429/qt8j647429.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 29.Canudas-Romo V, Aburto JM, García-Guerrero VM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mexico’s epidemic of violence and its public health significance on average length of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(2):188–193. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-207015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Igarapé Institute. The world’s most dangerous cities. 2017. Available at: https://igarape.org.br/en/the-worlds-most-dangerous-cities. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 31.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1 suppl 2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson JR, Hughes DC, George LK, Blazer DG. The association of sexual assault and attempted suicide within the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):550–555. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060096013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buka SL, Stichick TL, Birdthistle I, Earls FJ. Youth exposure to violence: prevalence, risks, and consequences. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(3):298–310. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Csete J, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M et al. Public health and international drug policy. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1427–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00619-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffman JS, Knox LM, Cohen R. Beyond Suppression: Global Perspectives on Youth Violence. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2011. [Google Scholar]