Abstract

In July 1973, a study at the University of Chicago linked radiation treatment during childhood to a variety of diseases, including thyroid cancer. A few months later, a worker at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois found a registry of 5266 former patients who had been treated with radiation during the 1950s and 1960s. Hospital officials decided to contact these patients and arrange for follow-up medical examinations. Media coverage of the hospital’s campaign had a snowball effect that prompted more medical institutions to follow suit, resulting in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) launching a nationwide campaign to warn the public and medical community about the late health effects of ionizing radiation. This study describes how the single action of a hospital in Chicago and the media attention it attracted led to a national campaign to warn those who underwent radiation treatment during childhood.

In 1952, three-year-old Rachel Warshaw-Dadon, who suffered from repeated bouts of tonsillitis, was given radiation therapy at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. In December 1973, she received an urgent notice from Michael Reese Hospital: “Attention, you might have thyroid cancer and we are responsible for it. We ask your forgiveness.”1 The letter directed her to go to the nearest reputable hospital to be tested for untoward results of the radiation therapy, with the expectation that she might have thyroid cancer. Rachel underwent several examinations and Michael Reese Hospital paid the expenses.

Michael Reese Hospital contacted Rachel as part of its campaign to examine its former patients with a record of radiation therapy. We describe the Michael Reese campaign, the media attention it attracted, and the snowball effect leading to other medical centers following suit and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) launching a nationwide campaign to warn the public and medical community of the late health effects of radiation treatment during childhood. We also present the history of the usage of radiation treatments for various benign diseases and review the first studies linking the treatments to serious late health effects, including cancer, discussing the uncertainties and controversies surrounding low-dose radiation and the role of the media, medical community, and national health authorities in raising awareness of radiation hazards.

USE OF X-RAYS FOR BENIGN DISEASES

The practice of using x-rays for the medical treatment of benign diseases began in 1910, peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, and then gradually became less frequent by the 1960s. Radiation therapy was considered to be good medical practice and a very effective treatment of benign illnesses, such as cervical adenitis, hemangiomas of the head and neck, tinea capitis (ringworm), birthmarks, infertility, pertussis, hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids, deafness, enlargement of the thymus gland (which was incorrectly believed to cause crib death), acne, and more.2 The immediate results were often promising. For example, acne scarring was reduced, some forms of deafness improved,3 and radiation treatment was very effective in eliminating ringworm.4

Head and neck radiation was a common practice worldwide.5 In the United States, more than two million people are estimated to have been treated with radiation for benign conditions.6 X-ray treatments gradually came to an end during the 1960s, after other effective treatments had been developed (e.g., griseofulvin for ringworm).7 At this time, studies started to report benign and malignant tumors of the thyroid gland, as well as leukemia, in individuals exposed to radiation during childhood, atomic bomb radiation, or fallout five or more years after the exposure.8

LONG-TERM ADVERSE EFFECTS OF RADIATION TREATMENT

Among the many risk factors for cancer, exposure to ionizing radiation is one of the most studied and measured epidemiologically. The primary reason is the exposure of large populations to radiation from the explosion of atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. These two events constituted one-time high external exposures to ionizing radiation (i.e., the entire dosage was absorbed by the entire body in a single incident).9

One of the first studies to show a link between brain tumors and therapeutic radiation to the head and neck following treatment of ringworm was published in 1968 by Albert and Omran10 from New York University. The study was an extension of earlier work by Albert et al.11 on patients who had undergone radiation treatment in the United States, which demonstrated a greater incidence of brain tumors among people who had been exposed to radiation to treat ringworm of the scalp as children. Following that study, numerous epidemiological articles were published on the link between childhood head and neck radiation and late health effects. The most influential study was published in 1973 by DeGroot and Paloyan from the University of Chicago, who found that 20 of 50 patients who had developed thyroid cancer as adults had received head and neck radiation during childhood 20 years or more prior.12 They concluded that many individuals in the United States who were treated with radiation as children had still not received follow-up medical care, and that an effort must be made to alert the public and physicians.13

Campaign to Locate Former Radiation Patients

Searching for the irradiated population.

A few months after DeGroot and Paloyan’s 1973 publication,14 a worker at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago found a box containing a registry of 5266 former patients who had been treated with radiation for benign diseases. The hospital had to make a decision about what to do with the registry and whether to contact the people and inform them that they were at greater risk of developing cancer. Although the x-ray therapy given at the time was considered effective and safe, the hospital feared that many patients would sue for medical damages.15 After much deliberation, and recognizing that radiation-associated thyroid carcinoma was an urgent problem, hospital officials decided to contact the patients and arrange for follow-up medical examinations.16

Ivan Dee, director of public relations at Michael Reese Hospital, described the situation to the Chicago Tribune:

There was a great dispute among the medical staff as to whether we should recall these patients and warn them of the danger. . . . The decision to go ahead was made on responsible ethical grounds. . . . We had a duty to our former patients to call them back for checkups.17

Efforts to contact former patients who were considered part of the population at risk began in December 1973, and in January 1974 Michael Reese Hospital began to examine those who had been contacted. To facilitate the program, letters were sent and phone calls made to all patients who may have undergone x-ray treatment and were at higher risk of developing thyroid cancer.18

Media coverage.

In early 1974, Michael Reese Hospital’s attempts to track down former patients for medical examinations started to appear in the media, especially newspapers.19 As a result, many additional former patients, or those who believed they underwent the treatment, began to contact the hospital for appointments and more information.20 Hospital officials realized that there were many more patients who were unaware of the late health effects of radiation and that a follow-up program was needed. Thus, efforts to contact former patients were renewed in July 1974.21 Medical malpractice suits that were submitted to the courts against the hospital were later dismissed. The courts accepted the hospital’s defense that, at the time, treating children with radiation was standard and considered an effective procedure, meaning that no malpractice was involved.22

Locating former patients was a complex task, as most had changed their original address, many did not remember or did not know that they or their relatives had undergone radiation treatment in childhood, and records were not always available.23 Despite these difficulties, Michael Reese Hospital made great efforts to locate its patients, often making many phone calls before giving up.24

The hospital’s campaign and the media coverage it attracted led other hospitals throughout Illinois, where the treatment was prevalent, to launch campaigns similar to those at Michael Reese. For example, in March 1974, Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago announced its attempt to locate former patients who were treated with radiation at the hospital more than 20 years prior.25 In Evanston in February 1975, an attempt was made to contact former patients at Evanston Hospital and a “recall clinic” was established to examine former patients.26 At this stage, national news channels started to cover the situation in Illinois. Programs describing the problem were broadcast, emphasizing the positive role of the media coverage that prompted more health institutions to search for their former patients. Media reports advised those who knew that they (or their children) had been exposed to radiation to contact their family doctor and arrange for an immediate thyroid examination.27

Expanding the Effort to Locate Former Patients

Because hospitals ran into difficulties locating former patients, Illinois state health authorities (e.g., Illinois Hospital Association, Illinois State Medical Society, and allied groups) joined the efforts to alert the public of the late effects of radiation. They used the media (newspapers and television) to reach a greater audience. As a result, thousands of former patients across Illinois started to contact medical centers and sought medical advice and examination.28

Media coverage of Michael Reese Hospital’s campaign promoted health institutions in other parts of the country to start their own campaigns to locate and examine people who had received radiation to the head and neck, including a screening program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In 1974, the Medical College of Wisconsin began to examine people who had undergone radiation treatment at the center and identified nearly 2000 patients.29

Media coverage of the situation in Chicago also led medical centers in Detroit, Michigan, to search for their former patients who had undergone radiation treatment as children. A unique situation was created in Detroit when a television journalist from Detroit’s Channel 4, Robert Vito, who himself had been treated with radiation at Michael Reese Hospital as a child, was contacted to come in for an appointment. After a cancerous growth was detected on his thyroid gland, Vito decided to single-handedly launch a campaign to locate patients at risk in the Detroit area. He began asking medical institutions one question: “When are you starting your recall program?”30

In February 1975, Vito began a series of reports on the radiation treatment he had received as a child and the cancer he developed, likely as a result. Six hours after the first report, his station was flooded with calls from 3000 people asking for more information. A short time later, at least 16 hospitals in the Detroit area began contacting their former radiation patients.31 Vito’s reports and publication in the media of the late health effects of radiation treatment led to many screening campaigns in Detroit and other locations throughout Michigan.32

Media coverage (radio, TV, and newspapers) of the issue had led many alarmed individuals and physicians to contact the NCI and other national health institutions and ask for more information. In response to these requests, on September 24–25, 1975, the NCI, together with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other organizations,33 held a medical conference on the late health effects of radiation to the head and neck in infancy and childhood. The goal of the conference was to improve communication with physicians regarding the late effects of radiation and guide medical centers on how to respond to the situation. At the conference, local hospitals were recommended to locate and examine their former patients, and a national strategy for coping with the situation was drafted.34

By 1976, continuous media reports led health officials in western Pennsylvania to search for tens of thousands of individuals thought to have received radiation to the head and neck.35 In the greater Pittsburgh area alone, medical authorities searched for a group of approximately 10 000 former patients who were exposed to possibly cancer-causing radiation treatment during childhood.36 In early 1977, medical centers in Connecticut began their own campaigns. Windham Community Memorial Hospital in Willimantic announced the beginning of a recall campaign to contact former patients in January.37 As with previous campaigns launched in other places, local and national media covered the story.38

In January 1977, the CBS News program 60 Minutes39 devoted a program to investigating the actions being taken by medical centers and national health authorities across the country to inform former irradiated patients about the late health effects of radiation. The program began by critically showing that, in most medical centers, no effective campaign had been launched to warn and bring in former patients for medical examinations, and only a few hospitals had taken it upon themselves to alert the public and trace former patients.40 The program ended by showing that, even though the national medical organizations involved (i.e., the American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association, and the NCI) encouraged all medical centers to start recall programs, only a few had done so. 60 Minutes investigators called 20 of the largest hospitals in the United States and found that no recall program was launched.41

THE NATIONAL CAMPAIGN TO WARN THE PUBLIC

Media coverage continued to grow, describing efforts made by medical centers throughout the United States to search for former patients as well as personal stories about people who had undergone radiation treatment. At this stage, the NCI recognized that the nation was facing a public health issue and that action was needed.

The National Cancer Institute Takes the Lead

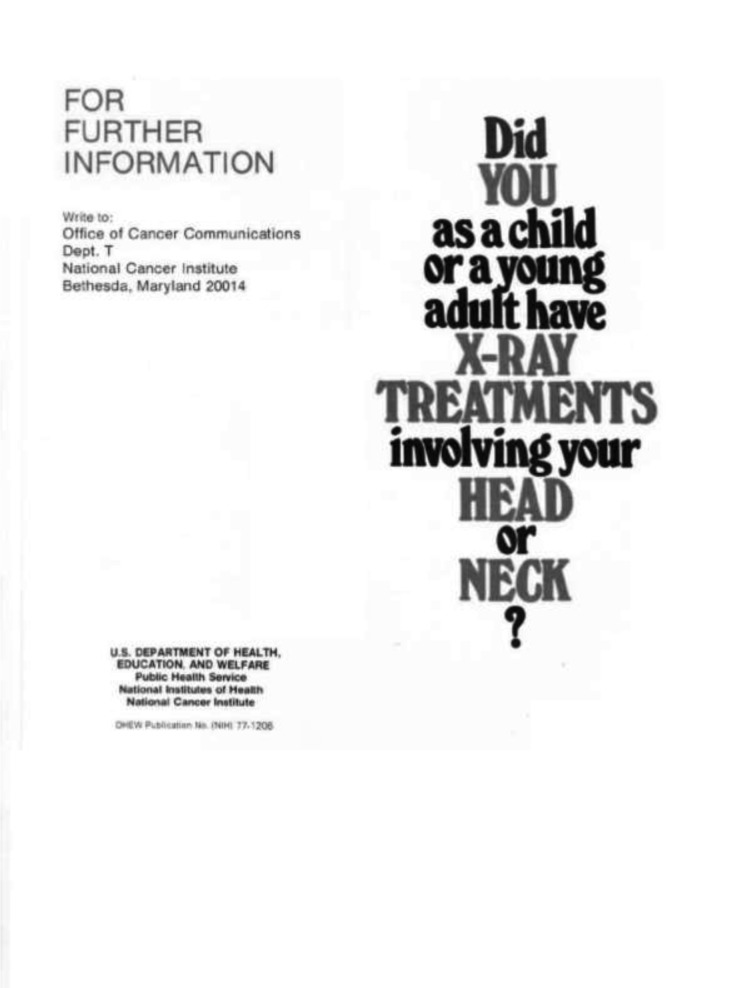

On July 13, 1977, the NCI launched a campaign about radiation-related thyroid cancer. The goal of the program was twofold. First, the NCI aimed to warn the medical community about the risk and to brief physicians on how to examine, diagnose, and treat thyroid tumors that were a consequence of past radiation treatment. To this end, the NCI published “Information for Physicians: Irradiation-Related Thyroid Cancer,” which could be ordered from the NCI’s central office in Bethesda, Maryland, at no charge. Second, they aimed to warn the public of the long-term risks of therapeutic radiation. Hundreds of thousands of pamphlets (Figure 1) were distributed in shopping centers across the United States, asking people who had undergone radiation treatment during childhood to go to their family doctor for a thyroid checkup:

Did you as a child or a young adult have x-ray treatments involving your head or neck?

If so, it is important that you have an examination by your physicians.42

FIGURE 1—

Original National Cancer Institute Pamphlet Distributed in July 1977

aFrom front page of pamphlet.50

In addition, notices were published in newspapers and television presenters opened their programs with warnings.43 The NCI’s campaign prompted more hospitals, which up to that time had not acted, to call their former patients for medical examinations.44 The campaign helped raise public awareness of the issue, prompting many individuals to contact their closest medical centers, and made the late effects of radiation known to the public. This campaign was one of the first in which national health authorities used the media to warn the public of the late effects of a standard treatment that was widely accepted.

The FDA’s Response

In June 1974, the FDA published a short article on the delayed effects of head and neck radiation45 in the FDA Drug Bulletin, a journal that aimed to improve communication between the FDA and practicing physicians.46 The Drug Bulletin quoted the studies in New York47 and Israel48 on neoplastic developments in persons who had had x-ray epilation for tinea capitis (ringworm). Casper Weinberger, secretary of the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), noted that the purpose of the article “was to alert physicians to possible delayed effects of ionizing radiation in individuals treated with x-ray for ringworm of the scalp.”49

Later, in September 1977, a few months after the NCI warned the public and the medical community, the FDA Bureau of Radiological Health published medical alerts for the professional community, summarizing the work of a committee established to investigate the health effects of ionizing radiation. “A Review of the Use of Ionizing Radiation for the Treatment of Benign Disease” included general recommendations for the medical profession regarding when and how to use the treatments, and provided information on the late effects. In both cases, the FDA communicated with physicians and not the public (Figure 2).51

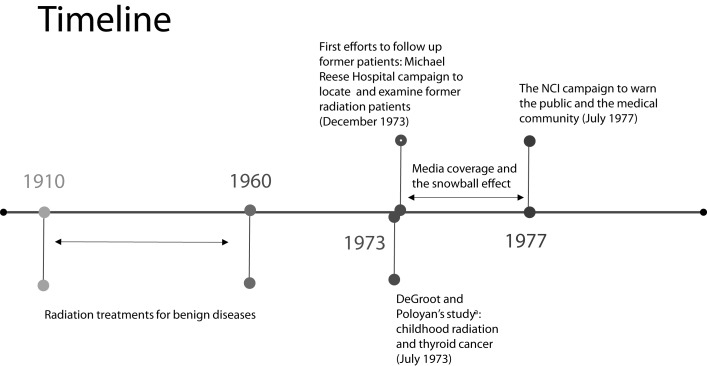

FIGURE 2—

Timeline of the History of the Radiation Treatment up to the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Campaign to Warn the Public in 1977

UNCERTAINTY, MEDIA REPORTS, AND THE NCI CAMPAIGN

The late health effects of radiation treatment appeared many years after the treatment was no longer administered; thus, ambiguity existed regarding whose role it was to assess and respond to the risks.52 The NCI acted as part of its responsibilities under the NCI Act of 1971. The agency acted during a period of transition (the late 1960s to early 1970s), from a focus on detection and treatment (i.e., control) to a focus on cancer prevention. The agency shifted its focus from educating the public and physicians about cancer and improving knowledge about the disease to preventing the further development of cancer already established in the body, giving more attention to preventable factors such as tobacco, asbestos, and radiation.53 In a way, the NCI’s campaign represented a combination of both eras: control and prevention. The campaign aimed to alert those who were at risk and to treat them (stressing that early detection of thyroid cancer saved lives), and to educate physicians and the public about the link between childhood radiation and thyroid cancer.54

The campaign was carried out during an era of uncertainty and controversy regarding the late health effects of low-dose radiation. The controversy of radiation risk mostly centered around atomic bomb radiation, atomic fallout, and exposure to nuclear plants. There was ambiguity regarding the lack of a threshold below which radiation was considered to be safe (i.e., tolerance dose) and the potential risk of radiation per year (i.e., maximum protection dose).55 In 1948, after the first data were collected from studies on atomic survivors, the US National Committee on Radiation Protection abandoned the concept of tolerance dose, realizing that even very low doses can be dangerous, replacing it with a maximum permissible dose standard.56 During the 1950s, more controversy ensued when the Atomic Energy Commission attempted to persuade the public that atomic energy was safe and did not pose a danger below a certain rate of exposure.57 This claim was criticized by critics of nuclear power and environmentalists who emphasized the danger of any exposure to radiation.58

The question of radiation safety moved beyond the strict scientific debate59 and became more politically sensitive. Considerations, such as whether the benefit of nuclear testing or nuclear plants outweighed the risk they posed, structured the debate as the public became more involved and anxious about radiation risks.60 In this context, when the treatment was no longer in use, more apparent links were established between the treatment and its late health effects.

The Michael Reese Hospital recall program, and the media attention it attracted, played an important role in informing the NCI of the severity and scope of the problem. The publicity garnered by the Michael Reese campaign prompted several health institutions to follow suit. However, most medical centers did not take action. One possible reason for their inaction was a fear of malpractice suits. As Ivan Dee, director of public relations at Michael Reese Hospital, noted: “Some [hospitals] were quite reluctant to follow our lead because they were afraid such a move would damage their reputation and cause legal problems.”61 According to Dee, the Michael Reese campaign was based on responsible ethical grounds.62

Those who decided to follow Michael Reese Hospital’s lead and start examining their former patients created more media attention and contributed to the snowball effect that led to a recognition of the link between thyroid gland tumors and radiation treatment during childhood. Although DeGroot and Paloyan’s study showed a more apparent link between radiation to the head and neck area during childhood and thyroid cancer than did previous studies, it is unlikely that a single study prompted national health authorities to launch a nationwide campaign. At that time, little was known about the size of the population at risk, and more data were required to determine the severity of the risk. As we have shown, media coverage played an important role in assisting national health authorities in obtaining this information, learning the scope of the problem, and realizing that the nation was facing a public health problem.

The relationship between the media and government is complex. Media reports can potentially inform governmental bodies about scandals, hazards, and other types of information. National health authorities care about media reports and, in some cases, they can affect their decisions.63 Media reports can assist national health agencies in discovering new sources of health hazards. For example, in his book The Cigarette Century, Brandt describes how an investigative TV program (Day One) revealed that the tobacco industry controlled the level of nicotine in the cigarettes it produced. The program prompted the FDA to try and act against the industry and to attempt to regulate nicotine under the agency’s authority.64 Media coverage can also draw attention to unethical misconduct in science. For example, it was only after national news brought the Tuskegee Syphilis Study to public attention in 1972 that HEW stopped the experiment.65 Media reports can also assist health authorities in determining the state of public knowledge of various diseases and their severity. For example, a “Report to Congressional Requesters” from the General Accounting Office argued that media reports of OxyContin misuse, addiction, and overdose deaths assisted the FDA in learning the scope and severity of the danger of opioid use.66 As a result, the FDA added a black box warning to the drug and changed the information on the package insert.67

Media coverage helped the NCI realize the severity and scope of the problem with childhood radiation in several ways. First, media reports of Michael Reese Hospital’s recall campaign prompted other medical centers to follow suit. As a result, more people with a history of radiation were examined, more research was done, and new scientific reports on radiation-induced thyroid cancer were published and a more certain link established. As mentioned in the HEW news publication on July 13, 1977,

From the experience of recall programs at several medical centers, it is estimated that a quarter to a third of the individuals irradiated develop thyroid tumors. Perhaps a third of such tumors are cancerous.68

It was the actions and new findings of various medical centers that helped the NCI realize that the nation was facing a public health issue.69

In addition, recall programs by various medical centers—a result of publicity from the Michael Reese campaign—brought to the NCI’s attention that there is a large population at risk that is hard to locate; thus, effective recalls are mostly logistically impossible and an effort should be made to alert these people.70 As an estimate of the number of irradiated people was not available, media reports of recall programs assisted the NCI in realizing that there was a very large population at risk.

Publication in the media also helped notify the NCI of the problem in a more direct way: newspapers, radio, and television publications had alarmed physicians and individuals (or parents who were aware of the radiation history of their children). This led to many requests for information and advice directed at the NCI and the National Institute of Arthritis, Metabolism, and Digestive Diseases by both physicians and individuals.71 As a result of the many requests, the NCI (and other organizations) held a medical conference on the late effects of radiation at which the recommendation to launch the campaign was discussed.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The decision of Michael Reese Hospital to recall former patients, the media attention it attracted, and the snowball effect it had played an important role in assisting national health authorities in determining the hazards of radiation treatment of benign diseases and responding to them. The sequence of events presented here emphasizes the role of the media as a tool that can possibly assist national health authorities in learning of new health risks. If the media had not picked up the story, millions of Americans who had undergone radiation treatment during childhood might not have known the dangers, as early detection of thyroid cancer saves lives.

No other country has warned the public of the adverse effects of radiation treatment of benign diseases. We find this puzzling. Further research on the existence or absence of national health institutions, such as the NCI, in other countries and the way they assess and respond to new health risks (e.g., their different levels of tolerance for uncertainty) is likely to improve our understanding of why only the United States warned the public of radiation hazards.

This report raises ethical and legal questions, such as the obligation of health authorities to warn patients of adverse effects of medical treatments, even if no malpractice was involved. It also raises the question of how effective the NCI’s nationwide campaign to warn the public was. Further research that collects data on the number of people who were examined because of the campaign is likely to shed new light on this issue and help write policy recommendations for similar instances. Finally, the case study described here can teach us how national health authorities share information with the public and physicians when a health problem is discovered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was funded by The Gertner Institute for Epidemiology and Health Policy Research, and we thank them for their generous support.

We thank Eli Shachar, Sari Levi, Sigal Samchi, and all the members of the National Center for Compensation of Scalp Ringworm Victims in Israel who contributed to this research with their helpful advice and comments. We also thank Barbara Faye Harkins and David Cantor of the National Institutes of Health, and Roger F. Robison, who assisted us in our archival work. We are grateful to Ciro Burstein and Aya Bar-Oz of The Gertner Institute for their important and generous help with this research. Special thanks to Judy Siegel-Itzkovich, The Jerusalem Post’s health and science editor, for her support and advice, which led many former patients across the world to contact us and provide valuable information. We thank political scientists Moshe Maor of the Hebrew University and Paul J. Quirk of the University of British Columbia for their invaluable suggestions, which contributed greatly to the quality of the article. Finally, we thank Susan Cox, Dan Steel, and David Silver of the W. Maurice Young Centre of Applied Ethics, University of British Columbia, for their support of this project.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See also Cantor, p. 347.

ENDNOTES

- 1. Interview with Rachel Warshaw-Dadon conducted by I. Bavli, March 1, 2012. The quote represents what she remembered as being in the letter and may be slightly different from the language as it appeared in the original letter, which she does not have. Mrs. Warshaw-Dadon provided us with written permission to quote her name in this interview.

- 2. C. Lenore Simpson, L. H. Hempelmann, and L. M. Fuller. “Neoplasia in Children Treated With X-Rays in Infancy for Thymic Enlargement,” Radiology 64, no. 6 (1955): 840–845; P. M. Crossland, “Therapy of Tinea Capitis—The Value of X-Ray Epilation,” California Medicine 84 (1956): 351–353; Y. G. Asherman, “Curative Irradiation of Menstruation and Fertility Disorders [in Hebrew],” Harefuah 50, no. 7 (1957): 163–165; W. M. Siskind and D. Richtberg. “Tinea Capitis in a City Hospital: Treatment With X-Ray,” New York State Journal of Medicine 58, no. 12 (1958): 2040; A. C. Cipollaro, A. Kallos, and J. P. Ruppe Jr, “Measurement of Gonadal Radiations During Treatment for Tinea Capitis,” New York State Journal of Medicine 59, no. 16 (1959): 3033–3040; V. B. Hocstaedt and G. Lager, “Curative Irradiation of Female and Menstrual Disorder: Setting Directives [in Hebrew],” Harefuah 56, no. 3 (1959): 70; National Cancer Program, “Special Communication: Irradiation-Related-Thyroid Cancer,” August 20, 1976; Paul G. Walfsh and Robert Volpe, “Irradiation-Related Thyroid Cancer,” Annals of Internal Medicine 88, no. 2 (1978): 261–262; Shifra Shvarts, Goran Sevo, Marija Tasic, Mordechai Shani, and Siegal Sadetzki, “The Tinea Capitis Campaign in Serbia in the 1950s,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 10, no. 8 (2010): 571–576. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. M. Sara Rosenthal, The Thyroid Cancer Book (Victoria, British Columbia: Your Health Press, 2002): 26–27; S. Sadetzki and B. Modan, “Epidemiology as a Basis for Legislation: How Far Should Epidemiology Go? The Lancet 353, no. 9171 (1999): 2238–2239. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. Alfred R. Maryanov, “Treatment of Tinea Capitis With Epilation by Means of Roentgen Rays,” Maryland State Medicine Journal 4, no. 1 (1955): 20–22; Crossland, “Therapy of Tinea Capitis”; Siskind and Richtberg, “Tinea Capitis in a City Hospital”; Cipollaro et al., “Measurement of Gonadal Radiations During Treatment for Tinea Capitis”; Shvarts et al., “The Tinea Capitis Campaign in Serbia in the 1950s”; Rosenthal, Thyroid Cancer Book, 26. [PubMed]

- 5. Rosenthal, Thyroid Cancer Book. For radiation treatment (1) in Serbia, see Shvarts et al., “The Tinea Capitis Campaign in Serbia in the 1950s”; (2) in France, see G. Tilles, Teignes et teigneux: Histoire médicale et sociale (Paris, France: Spinger Verlag France, 2009); (3) in Israel, see A. Bar-Oz, “The Truth About the Ringworm Affair [in Hebrew],” Harefuah 155 no. 10 (2016): 637–641. [PubMed]

- 6. Rosenthal, Thyroid Cancer Book, 28; “Thyroid Cancer Risk Linked to Children’s X-Rays,” The New York Times, June 24, 1977.

- 7. Y. Katzanelbugen and M. Zandbank, “Griseofulvin—A New Treatment for Fungal Diseases [in Hebrew],” Harefuah 57, no. 3 (1959): 59; H. Berlin, A. Tajer, and H. Yair, “Treatment with Griseofulvin for Ringworm and Select Cases of Fungus on the Skin and Nails [in Hebrew],” Harefuah 60, no. 4 (1960): 115–116.

- 8. B. J. Duffy Jr and P. J. Fitzgerald, “Cancer of the Thyroid in Children: A Report of 28 Cases,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 10 (1950): 1296–1308; D. E. Clark, “Association of Irradiation With Cancer of the Thyroid in Children and Adolescents,” Journal of the American Medical Association 10 (1955): 1007–1009; C. Simpson et al. “Neoplasia in Children Treated With X-Rays in Infancy for Thymic Enlargement”; J. M. Miller, R. C. Horn, and M. A. Block, “The Increasing Incidence of Carcinoma of the Thyroid in a Surgical Practice,” Journal of the American Medical Association 171 (1959): 1176–1179; E. L. Saenger, F. N. Silverman, T. D. Sterling, and M. E. Turner, “Neoplasia Following Therapeutic Irradiation for Benign Conditions in Childhood,” Radiology 74 (1960): 889–904; C. M. Riddley, “Basal Cell Carcinoma Following X-Ray Epilation of the Scalp,” British Journal of Dermatology 74 (1962): 222–224; E. L. Socolow, A. Hashizume, S. Neriishi, and R. Niitani, “Thyroid Carcinoma in Man After Exposure to Ionizing Radiation: A Summary of the Findings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” New England Journal of Medicine 268 (1963): 406–410; R. A. Conard, J. E. Rall, and W. W. Sutow, “Thyroid Nodules as a Late Sequela of Radioactive Fallout in a Marshall Island Population Exposed in 1954,” New England Journal of Medicine 274 (1966): 1391–1399; R. A. Conard, B. M. Dobyns, and W. W. Sutow, “Thyroid Neoplasia as Late Effect of Exposure to Radioactive Iodine in Fallout,” Journal of the American Medical Association 214 (1970): 316–324; National Cancer Institute, “Information for Physicians on Irradiation-Related Thyroid Cancer,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 26, no. 3 (May/June 1976).

- 9. Miron Israeli, Occupational Malignant Diseases and Compensation Schemes: A Report to the Rivlin Committee [in Hebrew] (Israel Committee of Nuclear Energy, 2013).

- 10.Albert R. E., Omran A. R. Follow-Up Study of Patients Treated by X-Ray Epilation for Tinea Capitis. Archives of Environmental Health. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1968.10665348. 17, no. 6 (1968): 899–918. The collection of data for the follow-up study began in 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert R. E., Omran A. R., Brauer E. W. et al. “Follow-Up Study of Patients Treated by X-Ray for Tinea Capitis”. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/ajph.56.12.2114. 56 (1966): 2114–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGroot L., Paloyan E. “Thyroid Carcinoma and Radiation. A Chicago Endemic”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 225, no. 5 (1973): 487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ibid, 491.

- 14. DeGroot and Paloyan, “Thyroid Carcinoma and Radiation”.

- 15.Ritter See J. “Once a Cure, Now a Threat”. Chicago Sun, March. 3, 2002, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frohman L. A., Schneider A. B., Favus M. J., Stachura M. E., Arnold J., Arnold M. “Thyroid Carcinoma After Head and Neck Irradiation: Evaluation of 1476 Patients”. In: DeGroot L., editor. in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1977. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotulak R. “Thyroid Tests; No Cover-Up,”. Chicago Tribune, March. 13, 1977, p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frohman et al., “Thyroid Carcinoma After Head and Neck Irradiation,” 5–15; L. A. Frohman, A. B. Schneider, M. J. Favus, M. E. Stachura, J. Arnold, and M. Arnold, “Risk Factors Associated With the Development of Thyroid Carcinoma and of Nodular Thyroid Disease Following Head and Neck Irradiation,” in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma, ed. L. DeGroot (New York, NY: Grune & Stratton, 1977), 231–240; J. Pearre, “X-Ray Malpractice Suit Dismissed Here,” Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1976, p.4.

- 19.Stone B. “Ex-Patients Hunted; Cancer Risk,”. Chicago Tribune, March 6, 1974, p 1. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frohman et al., “Thyroid Carcinoma After Head and Neck Irradiation,” 5.

- 21. Ibid.

- 22. See Pearre, “X-Ray Malpractice Suit Dismissed Here.”.

- 23. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, “HEW News,” July 13, 1977: 8; National Cancer Institute, “Information for Physicians on Irradiation-Related Thyroid Cancer.”.

- 24. J. Seligmann and M. Butler, “Dangerous Legacy,” Newsweek, April 14, 1975, p. 82.

- 25.Stone B. Ex-Patients Hunted: 2d Hospital Seeks Cancer-Risk Cases. Chicago Tribune , March 7, 1974, p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy E. D., Scanlon E. F., Swelstad J. A., Garces R. M., Khandekar J. D. “A Community Hospital Thyroid Recall Clinic for Irradiated Patients,”. In: DeGroot L., editor. Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton Inc; 1977. pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 27. NBC Evening News, February 14, 1975.

- 28. B. Stone, “X-Ray Treatment Patients Prove to Be Hard to Locate,” Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1975, p. A1.

- 29. J. M. Cerletty, A. R. Guansing, N. H. Engbring, et al., “Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma,” in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma, ed. L. DeGroot (New York, NY: Grune & Stratton Inc, 1977), 1–3. James Cerletty of the Endocrine Section, Department of Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, described how news coverage of Michael Reese’s campaign affected the decision to start studying the issue: “Our study [the screening program] was catapulted into action by publication in the press and by radio of a news bulletin announcing the Michael Reese thyroid recall project.” See James M. Cerletty, “The Organization, Publicity, Evaluation, Cost and Funding of a Thyroid Screening Program,” in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma, ed. L. DeGroot (New York, NY: Grune & Stratton Inc, 1977), 262.

- 30.Miller M. J. “The Metropolitan Detroit Area ‘Screening Program,’ ”. In: DeGroot L., editor. Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton Inc; 1977. p. 281. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seligmann and Butler, “Dangerous Legacy.”.

- 32. Ibid.

- 33. The other organizations were the National Institute of Arthritis, Metabolism, and Digestive Diseases; the Bureau of Radiological Health of the FDA; the American College of Radiology; and the American Thyroid Association.

- 34. National Cancer Program, “Special Communication: Irradiation-Related-Thyroid Cancer,” August 20, 1976.

- 35. R. G. Carroll, L. D. Ellis, D. Moore, et al., “Organization of Screening Program for Detection of Thyroid Cancer,” in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma, ed. L. DeGroot (New York, NY: Grune & Stratton Inc, 1977), 273. An estimated 70 000 subjects in Chicago, 10 000 in Milwaukee, and 20 000 in Pittsburgh had undergone radiation treatment; “Discussion of ‘Radiation and Thyroid Cancer Screening Programs—Summary of Experience in Current Programs,’ ” in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Carcinoma, ed. L. DeGroot (New York, NY: Grune & Stratton Inc, 1977), 42–43.

- 36. “Patients Irradiated Years Ago Sought Because of Cancer Peril,” New York Times, May 14, 1976, p. 91.

- 37. J. R. Ross, “Windham Hospital Begins ‘Recall’ of X-Ray Patients,” Hartford Courant, January 27, 1977, p. 33C.

- 38. Ibid.

- 39. “Deadly Medicine,” 60 Minutes, January 16, 1977.

- 40. Ibid.

- 41. Ibid.

- 42. These were the two sentences that appeared on the front page of the pamphlet (DHEW Publication No. [NIH] 77-1206, 1977).

- 43. Examples of such warnings: “Some Given X-Rays Told to Get Check,” Hartford Courant, July 17, 1977, p. 18A; “Tell Cancer Risk From Old X-Rays,” Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1977, p. B9; “US to Intensify Tumor Alert On X-Ray Therapy Long Ago,” Washington Post, July 7, 1977, p. A3; “US Issues Warning On Thyroid Cancer,” Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1977, p. C11; “National Cancer Institute Says Many Americans May Be at Risk of Thyroid Cancer Due to X-Rays of Neck and Head,” ABC Evening News, July 13, 1977; “National Cancer Institute Says X-Ray Treatments for Illness in Head and Neck Area May Increase Chances for Thyroid Cancer,” NBC Evening News, July 13, 1977.

- 44. For example, the state of New Jersey tried to work with hospitals and warn former patients; as a result, testing programs were launched throughout the state, including free screening for people who thought they may have been treated with radiation for benign diseases as children or young adults. See A. A. Narvaez, “Cancer Check Is Urged for Past X-Ray Care,” New York Times, August 6, 1977, p. 45.

- 45. “Head and Neck Radiation: Problem of Delayed Effects,” FDA Drug Bulletin, July 1974. Note that the bulletin concentrated on the delayed effects of radiation treatment for ringworm.

- 46.Schmidt A. M. “Letter: FDA Drug Bulletin,”. Clinical Toxicology. doi: 10.3109/15563657408988028. 7, no. 5 (1974): 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Albert and Omran, “Follow-Up Study of Patients Treated by X-Ray Epilation for Tinea Capitis.”.

- 48.Modan B., Mart H., Baidatz D., Steinitz R., Levin S. G. Radiation-Induced Head and Neck Tumours. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92592-6. 303, no. 7852 (1974): 277–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Epstein E. “Letter: FDA Drug Bulletin—Radiation”. Archives of Dermatology. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1975.01630190115020. 111 (1975): 925–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Front page of the pamphlet (DHEW Publication No. [NIH] 77-1206, 1977).

- 51. A Review of the Use of Ionizing Radiation for the Treatment of Benign Disease (Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1977), HEW Publication (FDA) 78-8043. Although public warnings are not common FDA practice, there is at least one known historical case. In 1956, the FDA launched a public campaign to warn the public about a fake cancer treatment. The treatment was offered by Harry Hoxsey’s clinic and promised hope and cure for people who had cancer. In April 1956, the FDA began distributing “public beware” posters to post offices across the United States, urging people not to go the Hoxsey clinic and inviting them to write the FDA for further information; D. Cantor, “Cancer, Quackery, and the Vernacular Meanings of Hope in 1950s America,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 6 (2006): 324–368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52. It was not clear whose role it was—the NCI’s or the FDA’s—to assess new health risks and respond to them. The FDA, the regulator whose role it is to protect the public health, monitors safety issues with drugs and treatments and has clear procedures on how to respond to safety problems that surface after approval of a drug or a treatment. The NCI is a research institute that investigates cancer risks.

- 53. D. Cantor, “Introduction: Cancer Control and Prevention in the Twentieth Century,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 81, no. 1 (2007): 1–38; see especially pp. 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54. Devra Davis challenged the view that national health institutions, such as the NCI, and regulatory bodies effectively worked to prevent cancer. She argued that hidden ties between the industry (such as chemical companies or big tobacco companies) and academic researchers and the government (among others) affected the way cancer risks were assessed. As a result, some of these risks were ignored, and actions aimed at protecting the public and preventing cancer took many years after the risks were already known (e.g., tobacco risks, workplace causes of cancer, chemicals). See D. Davis, The Secret History of the War on Cancer (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2007).

- 55. J. Samuel Walker, Permissible Dose: A History of Radiation Protection in the Twentieth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000); Robert N. Proctor, Cancer Wars: How Politics Shapes What We Know and Don’t Know About Cancer (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1996).

- 56. Walker, Permissible Dose; Proctor, Cancer Wars, 159; Sarah Dry, “The Population Is Patient,” in The Risks of Medical Innovation: Risk Perception and Assessment in Historical Context, ed. T. Schlich and U. Tröhler (New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2006), 116–132.

- 57. The US Atomic Energy Commission was established in 1946. Its main role was to protect the public health and safety from the dangers of radiation produced by nuclear fission. See Walker, Permissible Dose, 14.

- 58. Walker, Permissible Dose; Proctor, Cancer Wars.

- 59. For a more detailed explanation of the various studies and methods used to measure the effect of low-dose radiation, see Proctor, Cancer Wars, chapter 7.

- 60. Walker, Permissible Dose, 156.

- 61. Kotulak, “Thyroid Tests; No Cover-Up.”.

- 62. Malpractice suits were filed against Michael Reese after the hospital started the recall program in December 1973, but they were dismissed by the courts starting in December 1976 because radiation therapy was considered to be a safe and effective treatment at the time it was given. See Pearre, “X-Ray Malpractice Suit Dismissed Here.”.

- 63. See D. Carpenter, Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010); Moshe Maor, “Organizational Reputations and the Observability of Public Warnings in 10 Pharmaceutical Markets,” Governance 24, no. 3 (2011): 557–582; Moshe Maor and Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan, “The Effect of Salient Reputational Threats on the Pace of FDA Enforcement,” Governance 26, no. 1 (2013): 31–61.

- 64. A. M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2007), 358–361.

- 65.Brandt A. M. Racism and Research: The Case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Hastings Center Report. 8, no. 6 (1978): 21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Prescription Drugs: OxyContin Abuse and Diversion and Efforts to Address the Problem (Washington, DC: Government Accounting Office, 2003), Publication GAO-04-011, p. 9.

- 67. Ibid.

- 68. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, “HEW News,” July 13, 1977, p. 6.

- 69. Ibid.

- 70. The National Cancer Institute, “Information for Physicians on Irradiation-Related Thyroid Cancer.”. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71. Ibid, 151.