Abstract

In this article, we examine the role of nongovernmental entities (NGEs; nonprofits, religious groups, and businesses) in disaster response and recovery. Although media reports and the existing scholarly literature focus heavily on the role of governments, NGEs provide critical services related to public safety and public health after disasters. NGEs are crucial because of their ability to quickly provide services, their flexibility, and their unique capacity to reach marginalized populations.

To examine the role of NGEs, we surveyed 115 NGEs engaged in disaster response. We also conducted extensive field work, completing 44 hours of semistructured interviews with staff from NGEs and government agencies in postdisaster areas in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, Northern California, and Southern California. Finally, we compiled quantitative data on the distribution of nonprofit organizations.

We found that, in addition to high levels of variation in NGE resources across counties, NGEs face serious coordination and service delivery problems. Federal funding for expanding the capacity of local Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster groups, we suggest, would help NGEs and government to coordinate response efforts and ensure that recoveries better address underlying social and economic vulnerabilities.

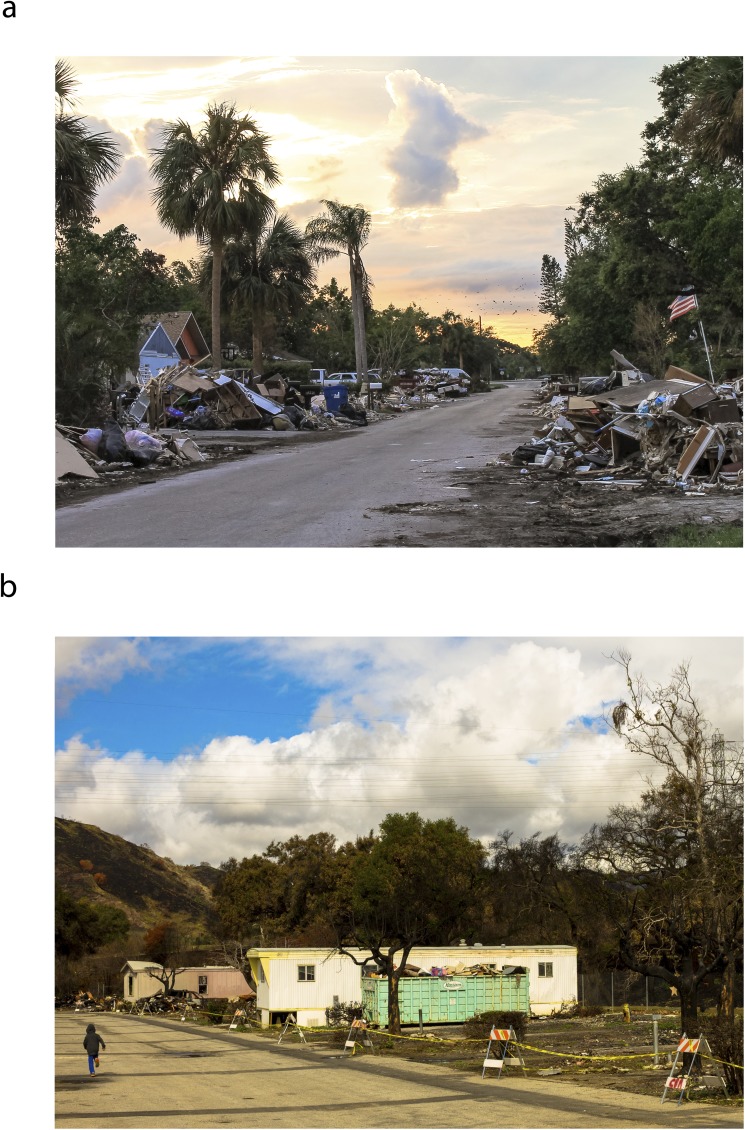

Disasters have significant implications for public health.1,2 Creating immediate risks to health and safety, events such as hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, earthquakes, and wildfires may also damage electrical grids, communications networks, and transportation infrastructure (Figures 1a and 1b). This leads to serious disruptions in patient care and in access to medical facilities and technology. In Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria, the result was a large-scale public health crisis and thousands of deaths.3,4 Over the long run, disasters may reshape local economies as well as neighborhoods and physical environments, with harmful consequences for those living on the social and economic margins.5–8

FIGURE 1—

Aftermath of (a) Hurricane Irma, Southwest Florida (October 2017), and (b) Thomas Fire, Southern California (March 2018)

Source. Photos by Daniel Sledge. Printed with permission.

Media discussions and the existing scholarly literature on disaster response and recovery focus heavily on the successes and failures of government. In this article, however, we examine the role of nongovernmental entities (NGEs) such as nonprofits, religious groups, and private businesses.9–14 Our analysis is grounded in research on the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, Hurricane Irma, and Hurricane Maria (each of which made landfall during 2017), as well as the massive 2017 wildfires in Northern and Southern California. We selected these cases because of their geographic variation, differing political and governmental contexts, and temporal proximity.15 We employed a mixed-methods research approach. First, we fielded surveys of NGEs engaged in disaster response. Second, we engaged in extensive field work, completing semistructured interviews with staff from NGEs and government agencies in postdisaster areas in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, Northern California, and Southern California. Finally, we compiled quantitative data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Census Bureau on the extent and distribution of nonprofit organizations.

We find that NGEs critically shape the path of disaster response and recovery. Formally included in the nation’s disaster response framework, NGEs are crucial because of their ability to quickly provide services that may not be provided by government, their flexibility, and their unique capacity to reach marginalized populations. Nonetheless, the prominence of NGEs in disaster response creates issues to which policymakers must be attuned.

Our analysis of IRS and Census data shows that NGE capacity varies significantly across communities. Whereas some communities possess robust nonprofit assets, others lack locally embedded capacity to provide postdisaster resources. Our surveys and in-depth interviews demonstrate that NGEs also face serious information constraints, limiting their ability to coordinate among each other and with government.16 This may lead to haphazard targeting of services and duplication of effort. Finally, our interviews suggest that NGEs are motivated by a variety of missions and strategies. Whereas some are formally committed to serving entire communities, others are focused on specific groups or categories of people.17

RESPONDING TO DISASTERS

Disasters require swift attention to public safety and health. Access to water, food, and shelter are pressing issues, as are mental health and emotional well-being.18,19 Disasters may also cause significant disruptions to health care systems, exacerbated by electricity outages, fuel shortages, and damage to transportation and communication infrastructure. For patients with chronic diseases, access to prescriptions, medical technology, and existing plans of treatment may be interrupted. Those with functional needs, residents of nursing homes, and dialysis patients also face high levels of risk.20–22

In the United States, disaster response is undertaken by local, state, and federal authorities, in conjunction with nonprofits, faith-based groups, and private businesses.12 Under the 1988 Stafford Act, presidential emergency and major disaster declarations may be made following the request of a governor, who must certify that local government is incapable of responding to a disaster on its own. Presidential declarations allow federal support to flow to US states, commonwealths, federally recognized Indian tribes, and territories.23,24

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) National Response Framework (NRF) lays out expectations about the role of different levels of government and of NGEs after a disaster.25 Under the NRF, local governments retain primary responsibility for preparing for and responding to disasters, with local first responders assisted by state and federal authorities. Along with FEMA, entities such as the National Guard, Army Corps of Engineers, and Environmental Protection Agency may take part in response efforts. Depending on the nature of the disaster, a presidential declaration may allow for the implementation of FEMA disaster programs, such as Individual Assistance, Public Assistance, and Hazard Mitigation Assistance. These programs cover an array of activities, including Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance, case management, and support for debris removal and infrastructure projects. FEMA assistance may be augmented by loans to individuals and businesses from the US Small Business Administration.

The box on page 439 outlines the roles the NRF assigns to government and NGEs. The NRF anticipates that nonprofits, religious groups, and businesses will provide key functions after a disaster. For nonprofits and religious groups, these include feeding, sheltering, case management, provision of health resources, management and coordination of volunteers and donations, and search and rescue support. For businesses, they include protecting privately owned critical infrastructure, commodity provision, and logistical support.

BOX 1— Roles of Governmental and Nongovernmental Entities Under National Response Framework.

| Government | Nongovernmental |

| Local government | Business |

| Maintains primary responsibility for preparing for and responding to man-made and natural incidents | Plans for, responds to, and recovers from incidents that impact privately owned critical infrastructure and facilities |

| State, tribal, territorial, and insular area government | Contributes to communication and information sharing during incidents |

| Supplements local efforts before, during, and after incidents | Provides commodities, services, and personnel to support response |

| When local resources are exceeded (or when this is anticipated), requests assistance from other states or from federal government via Stafford Act process | Nonprofit, voluntary, faith-based |

| Federal government | Provides emergency commodities and services including water, food, shelter, case management, clothing, health resources, and supplies |

| Following Stafford Act declaration, provides support to state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and local governments | Engages in and supports search and rescue, transportation, and logistics services |

| Coordinates response of federal agencies | Manages and coordinates volunteers |

| Takes leading role if federal jurisdiction | Identifies unmet needs |

RANGE OF NONGOVERNMENTAL ENTITIES

Under FEMA’s National Response Framework and in practice, NGEs provide crucial postdisaster services. These NGEs range from nonprofits and businesses with highly institutionalized response capabilities to groups with no previous experience. Larger organizations with extensive response and relief history, such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, often have seats in emergency operations centers during a disaster event. Local-level voluntary, civic, and religious groups are also prominent in activities such as distributing food and water and gutting water-damaged homes. Although these groups may face acute difficulties in assessing need and coordinating with each other and government, they may often be well-equipped to provide services to marginalized populations. Locally embedded groups, meanwhile, may be particularly responsive and accountable to community needs and concerns.17

The logistical capabilities of large businesses can facilitate deployment of needed goods. Wal-Mart, notably, maintains an emergency operations center with nationwide reach.27 Following Hurricane Harvey, supermarket chain HEB delivered water to the city of Beaumont, Texas, where the municipal water system was nonfunctional.28 For businesses, postdisaster work fulfills goals of community engagement and corporate responsibility along with restoring functionality to retail, office, or storage spaces. These efforts may also foster a positive public image. A 2018 Super Bowl ad, for instance, touted Budweiser’s delivery of water to disaster-impacted areas in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and California.29

EXAMINING NONGOVERNMENTAL ENTITY ROLES

To examine the role of NGEs in disasters, we engaged in a mixed-method approach, combining fieldwork and surveys with secondary data analysis. First, following disasters in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and Northern and Southern California, we conducted surveys of NGEs active in each area (n = 115). We identified NGEs through media reports, governmental and nonprofit assistance Web sites, and lists of community foundation grant recipients. Surveyed groups included nonprofit, civic, and charitable or philanthropic organizations (74.8% of respondents); faith-based groups (13.9%); and businesses (4.3%). Response rates ranged from 39.5% to 23.6% across the 5 disaster areas, with recruitment occurring in up to 3 waves of e-mails and supplemental telephone calls.

Second, we conducted in-person and telephone interviews with 57 respondents from government agencies and NGEs selected from survey lists or arranged through in-person contacts. We engaged in 2 waves of postdisaster fieldwork in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and 1 wave in both Northern and Southern California. Our fieldwork yielded 44 hours of in-depth, semistructured interviews, conducted in English and Spanish.

Finally, we compiled data on nonprofit resources from the IRS’s cumulative exempt business master files as well as county and Puerto Rican municipality-level population data from the US Census Bureau.

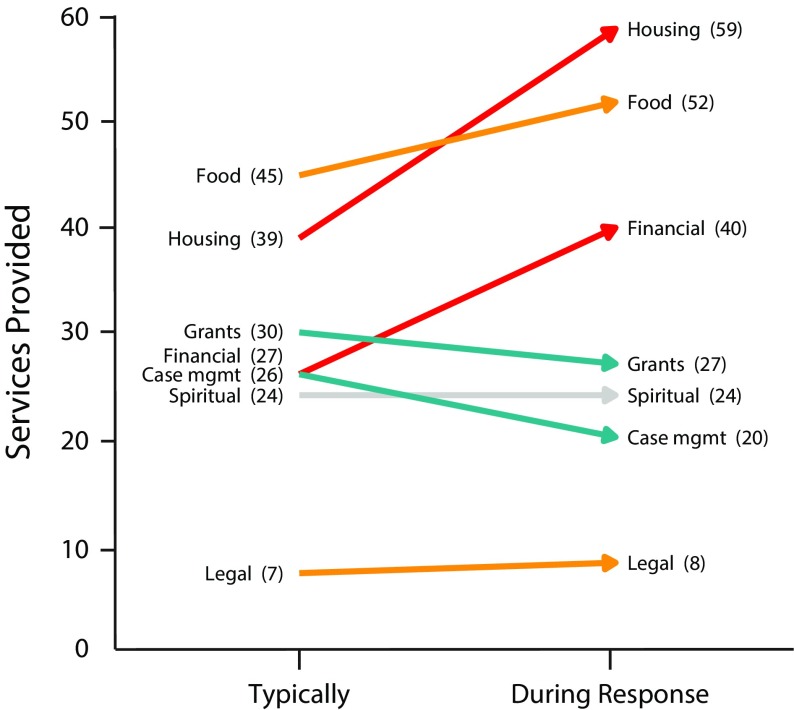

Our survey results emphasize the array of services that NGEs provide under normal conditions, as well as the shifts in their actions after disaster. As Figure 2 illustrates, the NGEs we surveyed often redirected their activities after disaster, moving toward housing-related services such as shelter, clean-up, and construction, as well as food assistance and emergency financial assistance. Following disaster, NGEs supplemented the capabilities of government by providing critical services.

FIGURE 2—

Services Provided by Nongovernmental Entities, Typically vs During Disaster Response: Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, Northern and Southern California, November—April 2018

Note. Mgmt = management. Data collected by author survey of 115 nongovernmental entities active in postdisaster areas. Housing includes shelter, clean-up, and construction; spiritual includes emotional, religious, and spiritual care.

These findings were reinforced by our postdisaster interviews, which highlighted the potential swiftness and flexibility of NGEs as well as NGE ability to engage with marginalized communities. A representative of a faith-based group active following Hurricane Harvey asserted that NGEs were critical because “government, in general, is very bad at moving quickly and immediately on a ground level.” In Puerto Rico, meanwhile, a representative from a major disease-related organization detailed her group’s shift toward providing basic necessities. Rather than focusing on facilitating treatment, as it would have before Hurricane Maria, the group recognized that its clients needed “water . . . food, gasoline for their generators—so we changed our program of work and started paying for those kind of things . . . that’s what people really needed at that time.” Adapting to developing circumstances, this organization relied on its existing client network to provide new services.

Discussing the role of government after Hurricane Irma, a member of a civic group in Southwest Florida emphasized her group’s sense of urgency: “[W]e can get the response out faster than the government can, and we’re not going to sit around and wait for somebody to do it. We need to help these people now.” This urgency was complemented by the recognition that the population her group sought to help included a number of undocumented immigrants who “might be afraid to get help from certain organizations” or “from the government.” As another member of the same group explained, “We actually made a conscious effort not to wear lanyards with name tags or anything like that—we didn’t want to look ‘official’ . . . . We didn’t want people seeing us and going into hiding. We’re there to help.” Other interview respondents routinely made similar statements about their ability, relative to that of government, to engage with marginalized communities.

To illuminate how NGEs perceived their roles relative to that of government, we asked survey respondents who would have provided the disaster-related services they rendered had they not been active. Fully 76.2% of surveyed NGEs reported that, had they not been active, their services may not have been provided (n = 101). Of these organizations, 40.3% believed that, if someone else did provide these services, it would have been another NGE that did so. Highlighting their perception of the unique nature of the services that they provided, only 16.9% of these NGEs believed government might have stepped in and provided their services had they not been active, and 13.0% believed that private contractors might have replaced NGE-provided services.

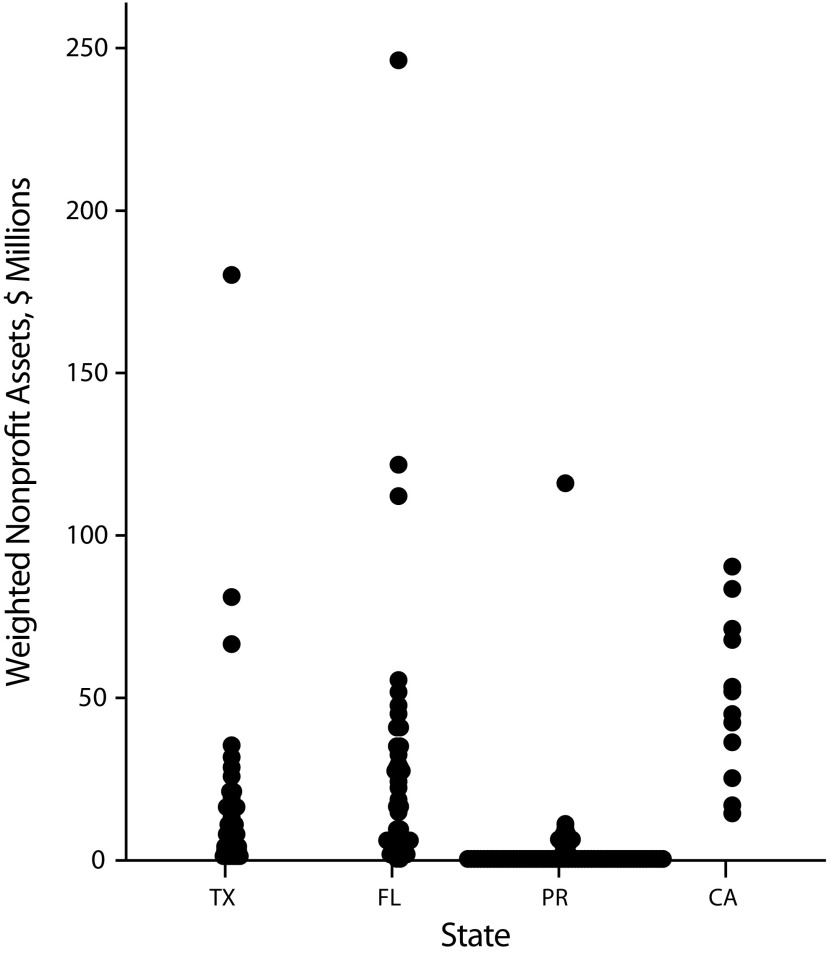

VARIATION IN NONGOVERNMENTAL ENTITY CAPACITY

Although NGEs play a critical role in the nation’s disaster response framework, substantial variation exists across communities in terms of NGE ability to deliver needed services.30,31 To measure and conceptualize NGE capacity, we compiled data on nonprofit assets in counties (in Puerto Rico, municipalities) in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and California impacted by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and by the 2017 California wildfires. Figure 3 plots nonprofit assets in disaster-declared counties in millions of US dollars, weighted per 10 000 population. Weighted assets, we observed, demonstrated high levels of dispersion. Some counties are home to robust nonprofit sectors, while others are characterized by comparatively low funding. Alachua County, Florida, for example, had the highest weighted nonprofit assets among disaster-impacted counties, at $246.3 million per 10 000 population. In Alachua County, 5414 people registered for FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program, which seeks to meet basic needs for disaster survivors.32 Four other Florida counties with comparable Individuals and Households Program registrations (ranging from 4672 to 5509) varied notably in the extent of their nonprofit assets. Our data show that Volusia County had $32.5 million in weighted assets, Orange County had $35.0 million, Lake County had $24.3 million, and Charlotte County had $6.5 million.

FIGURE 3—

Variation in Aggregated Nonprofit Assets Across Disaster-Declared Counties or Municipalities in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and California

Note. Data are nonprofit assets in millions of US dollars as reported to the Internal Revenue Service by organizations when revenues exceed $25 000 between June 2015 and June 2016 (Form 990), per 10 000 individuals residing in each county or municipality. Included counties or municipalities are those presidentially declared disaster areas receiving Federal Emergency Management Agency Individual Assistance following Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, and Northern and Southern California wildfires in 2017.

The variation in capacity identified by our analysis of IRS data emphasizes the importance of location. Whereas some communities possess significant locally embedded resources, others are relatively ill-equipped. In Puerto Rico, failures in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria stemmed in part from federal and commonwealth-level decisions and actions.33 They were also, however, the result of a national response framework that relies on NGEs, which were themselves overwhelmed by Maria or, in many areas, were not present or adequately funded. Given the assumptions of the National Response Framework, areas with large portions of the population living on the economic and social margins and relatively low nonprofit resources will face serious challenges in responding to and recovering from disasters.

COORDINATION

The NGEs that we surveyed following Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and the 2017 Northern and Southern California wildfires consistently highlighted information and coordination issues as postdisaster obstacles. Asked to rate their coordination on a 100-point scale ranging from “not effective” to “very effective,” the NGEs we surveyed reported highly varying experiences. Coordination was rated best among NGEs themselves, with a median of 79.4 (SD = 21.8). The mean response for coordination with local government was above “moderately effective,” at 61.0 (SD = 29.7). For state or commonwealth governments and the federal government, it fell just below “moderately effective,” to 49.0 (SD = 31.6) and 47.9 (SD = 29.8), respectively.

One means through which NGEs may coordinate is through an umbrella Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) group. The National VOAD organization provides a broad framework through which organizations may seek to coordinate their actions, share information, and more effectively target their efforts. Local chapters of state VOADs are sometimes known as Community Organizations Active in Disaster. The VOADs bring together NGEs active during disaster and representatives from government agencies, providing a platform for coordination. In some cases, local VOADs have seats in emergency operations centers. On Texas’s Gulf Coast, one VOAD representative who was in an emergency operations center during Hurricane Harvey described his role as “gathering information” and “distributing that out to everybody else,” so that VOAD-affiliated groups “had a situational awareness.” A representative from an international nonprofit that provided medical care following Hurricane Irma, meanwhile, noted that the “government typically relies on national and regional/local VOADs to facilitate coordination between voluntary organizations.”

The postdisaster interviews that we conducted highlighted the importance of VOADs in facilitating postdisaster coordination. In California’s wine country, a representative from the local branch of a major nonprofit described the difficulties that NGEs faced in Sonoma County, which did not have a county-level VOAD group. Community groups, he reported, had difficulty coordinating with the Red Cross, many of whose local volunteers were deployed to Texas and Florida as a result of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Although local groups began creating a VOAD after wildfires ravaged the area, “it wasn’t active prior to this, so from a volunteer perspective, people didn’t know where to donate items,” and there was no centralized information source. In neighboring Napa County, a Community Organizations Active in Disaster group (funded by a donation the local vintners’ trade association made after a 2014 earthquake) launched just before the wildfires. There, NGEs reported coordinating well with each other and with local government. As an important player in a Napa County nonprofit explained, the damage in Sonoma County differed in significant ways from that in Napa, “but the key difference here is that we had that [Community Organizations Active in Disaster] in place and they didn’t.”

For outside organizations, our postdisaster interviews made clear that coordination issues may prove acute during disaster response. From the perspective of local government officials, the influx of well-intentioned volunteers and groups may prove problematic. As an emergency management official in Southwest Florida described his experiences following Hurricane Irma, there is “never a commitment for routine communications.” Following disasters, groups may begin showing up on the scene within days, when “we’re so crazy busy, still responding, still putting out fires, still responding to 911 calls.” While groups may make contact with local officials, government is often stretched thin during the response period, and local authorities may not yet have completed situational assessments. In many cases, the official explained, groups “do their own situations assessment, and then I find out 24 hours later that they’re in the gymnasium at some church and that’s all I know.” In the official’s experience, the result was often that assistance from NGEs was not targeted at communities with the highest need. With a variety of NGEs seeking to become involved and with haphazard information sharing, disaster response may entail “enormous duplication of effort,” meaning that “a lot of money and a lot of resources” may be wasted.

SERVICE DELIVERY

The postdisaster interviews that we conducted highlighted the extent to which NGEs are motivated by differing missions and the variety of methods they employ to identify to whom they will provide services. Larger and more professionalized NGEs tend to have broad eligibility criteria and employ sophisticated demographic and mapping data. Other groups may rely on door-to-door canvassing, opportunity-based placement of service delivery, and media-driven targeting of response and relief efforts. Community embeddedness also played an important role in service delivery. As one individual involved in the response to Hurricane Irma explained, her group’s religious nature made it a beacon for the residents of an inland Florida town with a large immigrant farmworker population: “[B]ecause of our location on the church grounds . . . people in the community trust that this is a safe place for them to come. We didn’t need to advertise that we were a disaster site. People know and they show up.”

Groups with an existing client base often reported expanding from their targeted population to broader parts of the community. During a postdisaster interview in Puerto Rico, a staff member with a nonprofit that provided services for the homeless, including those with drug use disorders or HIV, described how Hurricane Maria impacted his organization’s mission. Following the hurricane, the organization sought to identify members of the homeless community with unmet needs but quickly decided that they would have to expand their reach. Though “our mission is for the homeless,” the representative explained, “we could not be blind toward the needs in the community, so we began to cook, not only for the homeless, but also for those persons in the communities.” Over the months that followed, the group pursued new funding to serve the broader community.

FROM RESPONSE TO RECOVERY

Government and NGEs play key roles in disaster response and recovery. Working together, they might pursue policies and efforts aimed at improving coordination and addressing social vulnerability to disasters.34,35 As a first step, the coordination issues that were routinely described during our postdisaster interviews might be addressed through a significant and ongoing federal commitment to helping fund state, regional, and county VOADs. This commitment should be pursued regardless of location or proximity to recent disasters. A vigorous locally embedded VOAD structure might also engage in outreach to organizations only intermittently involved in disaster response. Expanded resources for VOADs might prove particularly useful in areas where local NGE resources are comparatively limited, helping groups target their resources and providing a locally embedded structure for outside organizations to coordinate with during disaster response.

As scholars of social vulnerability have shown, susceptibility to disasters is shaped by underlying social structures, economic resources, and political relationships.5–7 Although disasters have an impact on individuals across social and economic categories, the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, and other marginalized groups are particularly susceptible to the adverse short- and long-run effects of disasters.6,36,37 Housing quality, location, and affordability, which are deeply interconnected with socioeconomic status, are key drivers of these outcomes.6

Interview respondents regularly highlighted the secondary economic impacts of disaster and government failures to address them. These impacts include displacement, unemployment, reduced wages because of decreased economic activity, and rising rental prices. Interview respondents drew attention to the long-term strain that disasters place on marginalized communities, along with a sense that these communities would likely receive little aid from government. Lack of access to safe and affordable housing was a consistent concern. They also noted that FEMA programs often appear to work most effectively for financially stable homeowners. In Puerto Rico, respondents explained that it was often difficult for homeowners to prove to FEMA that they owned their homes, given local building and land tenure practices. In one inland mountainous municipality, for instance, a government official reported (translated from Spanish) that the area’s primary long-run challenge was the “issue of home titles, which limits both federal and state help,” as residents were unable “to show that those are indeed their homes.”

While disasters often draw attention to the social and economic conditions that fuel community susceptibility, current federal policy is largely targeted toward a return to normalcy that may do little to address underlying issues of vulnerability within a community. A representative for a prominent antihomelessness nonprofit in the Houston, Texas, area was typical in expressing concern with FEMA’s underlying mission. “FEMA’s charge,” she pointed out, “is to return people to the state they were in prior to the storm.” As a result, “if you were living under a bridge prior to the storm, as long as you are living under the bridge after they leave, then they’ve done their job.”

Depending on the nature of a disaster and federal government decisions, recovery funds may be available from sources such as FEMA and the Small Business Administration. Disaster-specific federal Community Development Block Grants may also be available, although they are contingent on supplemental congressional appropriations.38 Following Hurricane Katrina, however, empirical evidence demonstrates that federal funding for permanent housing, including funding from FEMA and from Community Development Block Grants, was heavily slanted over the long run toward owner-occupied homes over rental units.39 Meanwhile, FEMA’s 2011 National Disaster Recovery Framework, which pays attention to health, housing, infrastructure, and sustainability, has only partially been implemented. State and local governments have expressed confusion about its relation to their efforts and those of federal agencies.40 Although federal money may be available for disaster unemployment insurance, this is a short-term program with strict eligibility requirements. There is no recourse for undocumented workers, though their American-born children may be eligible for some programs.

The cascading economic and social effects of disasters require recovery efforts that are flexible and attuned to local conditions. Expanded resources for locally embedded VOADs might provide a pathway toward addressing the needs of the poor, minorities, and other marginalized groups throughout the recovery process. During the period between initial disaster response and the release of federal recovery funding, NGEs are critical in responding to unmet needs related to housing, construction, clean-up, and financial strain. Effective VOADs facilitate the formation of Long-Term Recovery Groups, which bring together NGE resources to help families recover. High-quality Long-Term Recovery Groups may provide an effective means of helping government officials and NGEs to pursue recovery efforts that address underlying community vulnerabilities and rebuild in a manner that fosters resilience.

CONCLUSIONS

Relying on survey data, field research, and analysis of IRS data on nonprofits, we examined the role of NGEs during disaster response and in disaster recovery. Under FEMA’s National Response Framework and in practice, NGEs address issues of public safety, health, housing, and economic strain. Our surveys and field research show that NGEs are capable of adapting swiftly and providing services to populations that might be overlooked or wary of interacting with government. As a result, they are well-equipped to address gaps in government ability to address the needs of the marginalized populations that are particularly vulnerable to disasters.

Our analysis of IRS data, however, demonstrated high levels of variation in locally embedded nonprofit resources across counties. While some communities are well-positioned to respond to disasters and to engage in long-term recovery, others are not. In addition, our surveys and interviews highlighted the challenges that NGEs face in coordinating with each other and with government. Our research also draws attention to the differing strategies that NGEs use to identify to whom they will provide services.

As a means of better coordinating response efforts and ensuring that recoveries address underlying social and economic vulnerabilities within a community, the federal government should make an ongoing commitment to funding locally embedded VOADs, regardless of an area’s proximity to recent disasters. Expanded resources for VOADs would improve information sharing and coordination capabilities, helping NGEs to better target their actions and increasing NGE impact in areas with comparatively limited nonprofit resources. Effective VOADs, meanwhile, will facilitate the creation of long-term recovery groups that address underlying community vulnerabilities, helping to reduce local susceptibility to future disasters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant 1800302.

We thank Josué Rosales Rodriguez and Nikita Webb for their invaluable research assistance. We are also thankful to Derek Epp, Zac Greene, George Sledge, Heather Hughes, and Herschel Nachlis for their feedback on this project at various stages. We thank Maranda Spencer, Courtney Pool, and Julian Rangel for providing additional research assistance. We deeply appreciate the feedback and comments we received from anonymous reviewers and from the journal editor. This project was facilitated by the efforts of Ami Keller, Kim Bell, and Rebecca Deen. The University of Texas, Arlington, provided additional research support. We also acknowledge Andrew Caird for providing data visualization code.

Note. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The institutional review board at the University of Texas, Arlington, concluded that our study did not meet the criteria for human participant research given our focus on organizational behavior. We collected written or audio informed consent for all interviewees.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zolnikov TR. A humanitarian crisis: lessons learned from Hurricane Irma. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):27–28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtveld M. Disasters through the lens of disparities: elevate community resilience as an essential public health service. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):28–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):162–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Díaz CE. Maria in Puerto Rico: natural disaster in a colonial archipelago. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):30–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutter SL, Emrich CT. Moral hazard, social catastrophe: the changing face of vulnerability along the hurricane coasts. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2006;604(1):102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fothergill A, Peek LA. Poverty and disasters in the United States: a review of recent sociological findings. Nat Hazards. 2004;32(1):89–110. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergstrand K, Mayer B, Brumback B, Zhang Y. Assessing the relationship between social vulnerability and community resilience to hazards. Soc Indic Res. 2015;122(2):391–409. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0698-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platt Boustan L, Kahn ME, Rhode PW. The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in US counties: a century of data. NBER Working Paper 23410. National Bureau of Economic Research. May 2017. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w23410. Accessed July 4, 2018.

- 9.Murthy BP, Molinari NM, LeBlanc TT, Vagi SJ, Avchen RN. Progress in public health emergency preparedness—United States, 2001–2016. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(suppl 2):S180–S185. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz R, Attal-Juncqua A, Fischer JE. Funding public health emergency preparedness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(suppl 2):S148–S152. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes MD, Hanson CL, Novilla LM, Meacham AT, McIntyre E, Erickson BC. Analysis of media agenda setting during and after Hurricane Katrina: implications for emergency preparedness, disaster response, and disaster policy. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):604–610. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber BJ. Disaster management in the United States: examining key political and policy challenges. Policy Stud J. 2007;35(2):227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eller W, Gerber BJ, Branch LE. Voluntary nonprofit organizations and disaster management: identifying the nature of inter-sector coordination and collaboration in disaster service assistance provision. Risks Hazards Crisis Public Policy. 2015;6(2):223–238. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gajewski S, Bell H, Lein L, Angel RJ. Complexity and instability: the response of nongovernmental organizations to the recovery of Hurricane Katrina survivors in a host community. Nonprofit Volunt Sector Q. 2010;40(2):389–403. [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Government Accountability Office. hurricanes and wildfires: initial observations on the federal response and key recovery challenges. 2018. 2017. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-472. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 16.Robinson SE, Berrett B, Stone K. The development of collaboration of response to Hurricane Katrina in the Dallas area. Public Works Manag Policy. 2006;10(4):315–327. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cammett M, MacLean LM. The Politics of Non-State Social Welfare. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2014. The political consequences of non-state social welfare: an analytical framework; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills MA, Edmondson D, Park CL. Trauma and stress response among Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(suppl 1):S116–S123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neria Y, Shultz JM. Mental health effects of Hurricane Sandy: characteristics, potential aftermath, and response. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2571–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.110700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peek L, Stough LM. Children with disabilities in the context of disaster: a social vulnerability perspective. Child Dev. 2010;81(4):1260–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jan S, Lurie N. Disaster resilience and people with functional needs. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(24):2272–2273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1213492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Xirasagar S, Cornman CB, Davis CB, Richter JVE. Providing shelter to nursing home evacuees in disasters: lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1288–1293. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.107748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts PS. Disasters and the American State: How Politicians, Bureaucrats, and the Public Prepare for the Unexpected. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downton M, Pielke R. Discretion without accountability: politics, flood damage, and climate. Nat Hazards Rev. 2001;2(4):157–166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Response Framework. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Homeland Security; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Government Accountability Office. Voluntary organizations. 2008. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08823.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- 27.Horwitz S. Making Hurricane Response More Effective: Lessons From the Private Sector and the Coast Guard During Katrina. Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center, George Mason University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solomon D. How H-E-B took care of its communities during Harvey. Tex Mon. 2017;(September):7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monllos K. Budweiser highlights disaster relief efforts, real employees in 60-second Super Bowl spot. AdWeek. January 26, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allard SW. Places in Need: The Changing Geography of Poverty. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allard SW. Out of Reach: Place, Poverty, and the New American Welfare State. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Federal Emergency Management Agency. Individual assistance open disaster statistics. Available at: https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/132213. Accessed June 8, 2018.

- 33.US Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2017 hurricane season FEMA after-action report. 2018. Available at: https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1531743865541-d16794d43d3082544435e1471da07880/2017FEMAHurricaneAAR.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018.

- 34.Gerber BJ, Robinson SE. A seat at the table for nondisaster organizations. Public Manage. 2007;36(3):4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egan MJ, Tischler GH. The national voluntary organizations active in disaster relief and disaster assistance missions: an approach to better collaboration with the public sector in post-disaster operations. Risks Hazards Crisis Public Policy. 2012;1(2):63–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinn SC. Hurricane Katrina: a social and public health disaster. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):204. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodie M, Weltzien E, Altman D, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Experiences of Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston shelters: implications for future planning. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1402–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyd E. Community Development Block Grant Funds in Disaster Relief and Recovery. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Government Accountability Office. Disaster assistance: federal assistance for permanent housing primarily benefited homeowners; opportunities exist to better target rental housing needs. 2010. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/310/300098.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- 40.US Government Accountability Office. Disaster recovery: FEMA needs to assess its effectiveness in implementing the National Disaster Recovery Framework. 2016. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/677511.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018.