Purpose:

We sought to describe practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to the integration of palliative care services by gynecologic oncologists.

Methods:

Members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology were electronically surveyed regarding their practice of incorporating palliative care services and to identify barriers for consultation. Descriptive statistics were used, and two-sample z-tests of proportions were performed to compare responses to related questions.

Results:

Of the 145 respondents, 71% were attending physicians and 58% worked at an academic medical center. The vast majority (92%) had palliative care services available for consultation at their hospital; 48% thought that palliative care services were appropriately used, 51% thought they were underused, and 1% thought they were overused. Thirty percent of respondents thought that palliative care services should be incorporated at first recurrence, whereas 42% thought palliative care should be incorporated when prognosis for life expectancy is ≤ 6 months. Most participants (75%) responded that palliative care consultation is reasonable for symptom control at any stage of disease. Respondents were most likely to consult palliative care services for pain control (53%) and other symptoms (63%). Eighty-three percent of respondents thought that communicating prognosis is the primary team’s responsibility, whereas the responsibilities for pain and symptom control, resuscitation status, and goals of care discussions were split between the primary team only and both teams. The main barrier for consulting palliative care services was the concern that patients and families would feel abandoned by the primary oncologist (73%). Ninety-seven percent of respondents answered that palliative care services are useful to improve patient care.

Conclusion:

The majority of gynecologic oncologists perceived palliative care as a useful collaboration that is underused. Fear of perceived abandonment by the patient and family members was identified as a significant barrier to palliative care consult.

INTRODUCTION

Gynecologic cancers, which include cancer of the uterine corpus, uterine cervix, ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, and vulva, collectively compose the third most common cancer type and cause of cancer deaths in the United States, after breast and lung cancers.1 More than 1 million women are living with ovarian, uterine, and cervical cancer in the United States.2 A large portion of this patient population will require a multidisciplinary approach to treat the complex symptoms associated with disease, treatment, recurrence, and advanced cancer at the end of life. Specialist palliative care teams play a valuable role in the management of patients with cancer as a result of their ability to help manage difficult symptoms, assist with patient and family coping, promote illness understanding, and provide education.3 Palliative care providers may also help patients articulate their goals of care, provide psychosocial support, and assist with transition to hospice.

Palliative care has a wide range of benefits for patients with cancer, such as the improvement of symptoms, quality of life, and mood and the reduction of nonbeneficial and potentially harmful interventions and receipt of aggressive care at the end of life.4-8 Improved survival with integration of palliative care medicine is another potential benefit, as demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial in non–small-cell lung cancer.4 In response to the growing body of literature supporting the benefits of palliative care involvement in patients with cancer, both ASCO and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) released official practice guidelines in 2012 (updated in 2016) and 2015, respectively, encouraging the routine incorporation of palliative services to improve quality of care.9-11 The most recent ASCO update specifies that patients with advanced cancer should be referred to palliative care services within 8 weeks of diagnosis.10

Even though gynecologic oncologists are prepared and want to deliver palliative and end-of-life care, studies consistently show that palliative care services are underused throughout the disease trajectory, including at the end of life, in a patient with cancer. For example, in a recent study among gynecologic oncology patients who met ASCO criteria for palliative care consultation, only 53% received a palliative care consultation.12 Similarly, at a comprehensive cancer center, only 45% of patients who died of cancer had a palliative care consultation by the end of life.13 Others report that the median time from palliative care consultation to death is 6 to 7 days.14 Timing of palliative care consultation is important, because outpatient referrals tend to result in longer hospice stays with improved end-of-life care.4,7 Excess futile interventions at the end of life and the elevated proportion of patients dying in the hospital or shortly after discharge can be partially explained by late participation in hospice care.9,15

Inpatient hospitalizations for patients with cancer are often a time for patients to address goals of care, clarify treatment plans, and improve symptom control and are a common point of intersection of oncologists and palliative care providers. Several barriers to the integration of palliative care services have been identified, mostly involving misconceptions by patients, their families, and physicians about the breadth and benefits of palliative care.16-20 Given the documented underutilization of palliative care services in patients with gynecologic cancers leading to excessive use of aggressive and nonbeneficial interventions at the end of life, we sought to explore the practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to the integration of palliative care services among gynecologic oncologists.15,21-24

METHODS

A survey was created on the basis of common barriers reported in the literature to the incorporation of palliative care services in oncology. A pilot survey was administered to the attending physicians at the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at Columbia University Medical Center (New York, NY). Their feedback was used to finalize the questionnaire. The survey consisted of 27 items to evaluate practice patterns, attitudes, and barriers to the incorporation of palliative care services as identified in previous literature and was anonymously administered to SGO members.16,25 We collected demographic data and explored perceived competence with various palliative care tasks (eg, discussion of prognosis, do not resuscitate [DNR]/do not intubate [DNI] orders), perceived responsibilities as primary oncologists and as palliative care consultants, perceived benefits and barriers to the incorporation of palliative care services, and general attitudes about the collaboration between the two teams. The survey was reviewed and edited by members of the gynecologic oncology and palliative care divisions at our institution. After Institutional Review Board approval at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the survey was sent to all members of the SGO who had e-mail addresses available in the SGO directory using a Web-based, commercially available survey software program. The survey was sent a total of three times between July and August 2015. Participation was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. Descriptive statistics were calculated using the Web-based commercially available survey software program. Two-sample z-tests of proportions were performed to compare the responses regarding confidence to perform various palliative care tasks and responses regarding the likelihood to consult palliative care for those same tasks. We used STATA version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for our calculations.

RESULTS

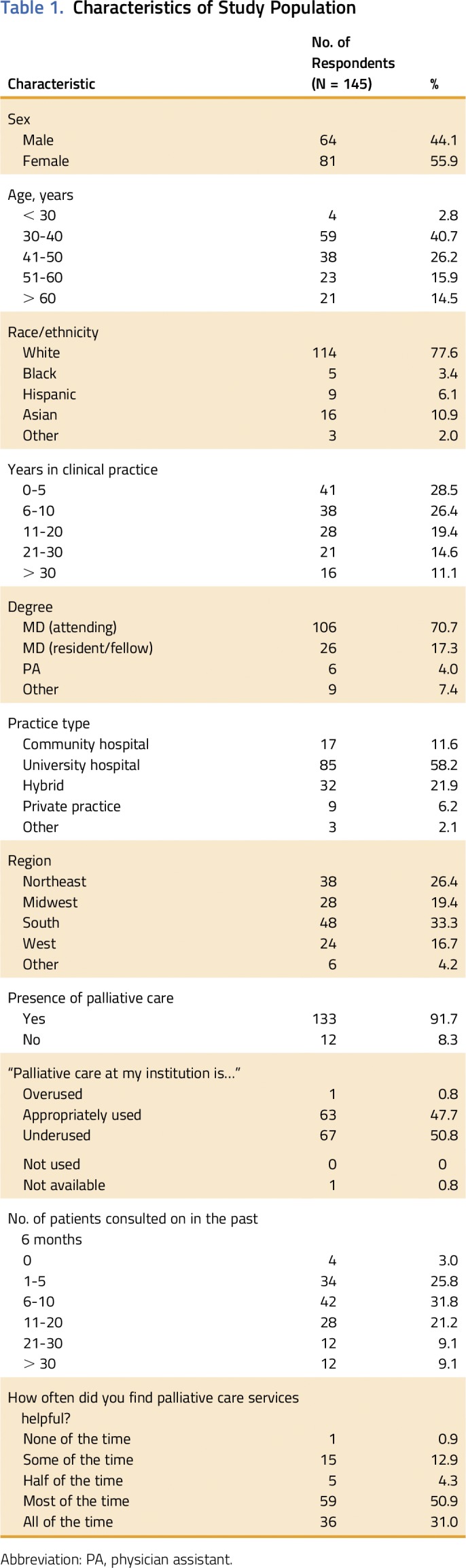

We sent the survey to 709 SGO members and received 145 responses (20% response rate). Most respondents were white (78%), women (56%), age 30 to 50 years (67%), had < 10 years of attending clinical practice (55%), and worked in a university-affiliated hospital (58%; Table 1). These demographic characteristics are similar to those of the SGO membership.26 As published in the 2015 State of the Subspecialty Report, 78% of gynecologic oncologist SGO members identified themselves as white, 61% were age 30 to 50 years, and 46% had < 10 years of clinical practice.26 The geographic distribution of our survey respondents was also remarkably similar to that of the membership. In our survey, 26%, 19%, 33%, and 17% of gynecologic oncologists practiced in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West, respectively, whereas 26%, 19%, 35%, and 20% of SGO members practice in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West, respectively.26

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population

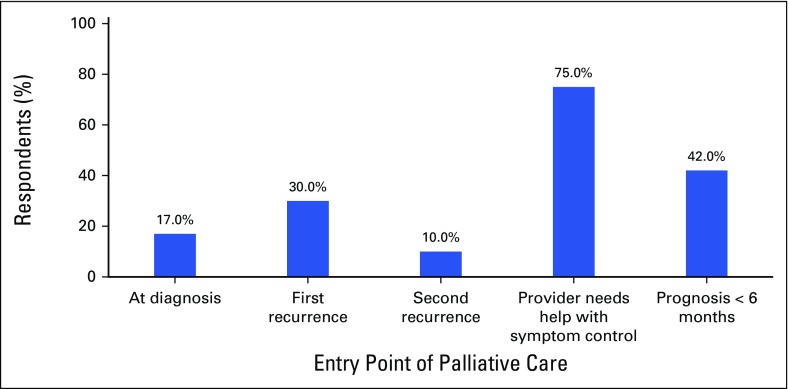

Most respondents (92%) reported having a palliative care team at their hospital, and approximately half (51%) reported that they underused palliative care services. Thirty-two percent estimated they had consulted palliative care for six to 10 patients in the previous 6 months, and 39% estimated they had consulted palliative care for > 10 patients. Most respondents (75%) feel that it is appropriate to consult palliative care at any time during the course of the disease to assist with symptom control; 42% of respondents believe that it is appropriate to consult palliative care when the patient has a life expectancy of less than 6 months, whereas only 17% think that it is appropriate to consult palliative care at the time of diagnosis (Fig 1). Few providers were “very likely” to consult palliative care providers to communicate prognosis, discuss DNR/DNI status, or discuss goals of care (9%, 10%, and 21%, respectively).

Fig 1.

Percentage of respondents favoring palliative care involvement at different points in the disease course.

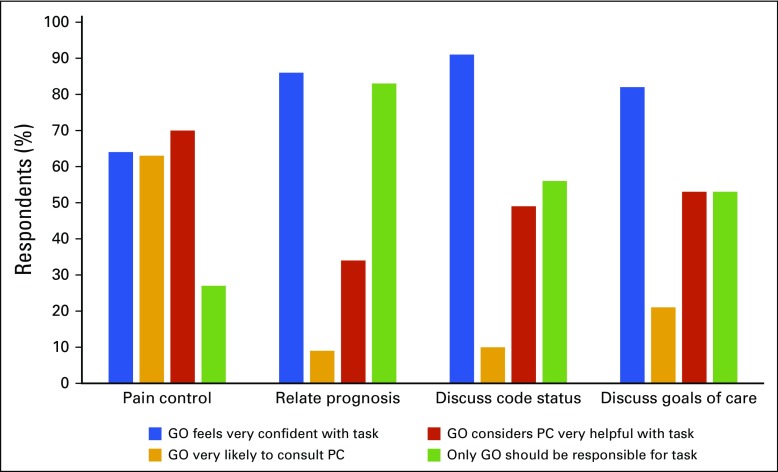

The survey also addressed self-assessment of competence in various aspects of palliative and end-of-life care and which care team should be responsible for these aspects. Respondents perceived themselves as “very competent” to communicate prognosis (86%), discuss DNR/DNI status (91%), and discuss goals of care (82%), which is consistent with not being “very likely” to consult palliative care for these tasks. When asked which team should be responsible for these tasks, 69% of respondents answered that both teams should be responsible for pain control, whereas 83%, 56%, and 46% of respondents indicated that the gynecologic oncology team should be solely responsible for communicating prognosis, discussing DNR/DNI status, and discussing goals of care, respectively (Fig 2). There was a negative association between the percentage of respondents who feel “very competent” with communicating prognosis (86%), discussing DNR/DNI status (91%), and discussing goals of care (82%) and the percentage of respondents who are “very likely” to consult the palliative care team for these tasks (9%, 10%, and 21%, respectively; P < .001 for all). The majority of providers also felt “very competent” to manage pain control (64%), but 69% perceived this task as a shared responsibility (Table 2). There were no significant differences in the percentage of respondents who reported they were “very likely” to consult palliative care for pain control or other symptom control and the percentage of respondents who reported they were “very competent” with these skills (pain control, P = 1.000; other symptom control, P = .759). Even though < 50% of respondents felt “very confident” with discussing health care proxy (46%), only 22% felt “very likely” to consult palliative care for this task (P = .001). Palliative care providers were perceived as “very helpful” for pain control, symptom control, discussing DNR/DNI status, discussing goals of care, and discussing prognosis by 70%, 63%, 49%, 53%, and 34% of respondents, respectively (Table 2).

Fig 2.

Gynecologic oncologist (GO) self-perceived confidence with palliative care (PC) tasks and attitudes toward PC consultation.

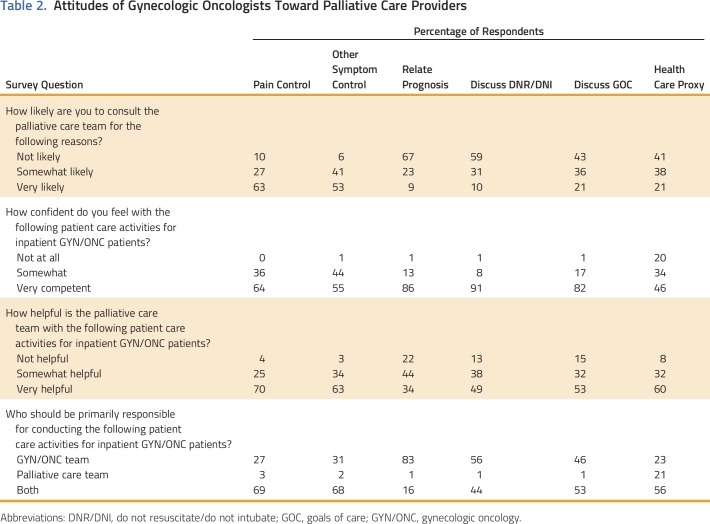

Table 2.

Attitudes of Gynecologic Oncologists Toward Palliative Care Providers

In addition, we asked participants what they think are the benefits of palliative care for patients and families and about the barriers or disadvantages in their practice setting for consulting palliative care for inpatients. The gynecologic oncologist respondents found the greatest benefit from palliative care consultation when transitioning to end-of-life care. Respondents perceived the following benefits for patients and their families: transition to end-of-life care (95%), grief counseling (87%), spiritual support (81%), reduction of futile interventions (74%), discussion of goals of care (73%), and communication of prognosis (54%). The main barriers to consulting palliative care were the concern that the patient and family would think the primary provider was giving up on the treatment of the patient (90%) and family resistance (80%). Lack of availability (22%), lack of timely access (20%), fear of increasing length of hospital stay (11%), and prior inpatient conflict with the palliative care team (11%) were not seen as significant barriers by most respondents.

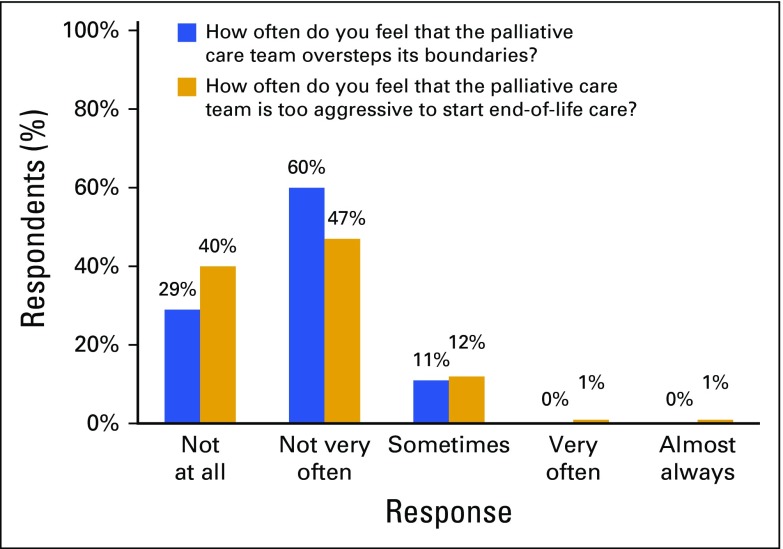

Regarding the general feelings about the collaboration between the two teams, gynecologic oncologists overwhelmingly (97%) reported that palliative care teams are a useful adjunct to patient care, with only 2% responding that the palliative care team neither adds nor detracts from patient care and 1% responding that the palliative care team interferes with patient care. However, 21% of respondents reported that they have had a negative experience with a palliative care team that has made them reluctant to consult the team in the future, and 30% reported that they either often or sometimes feel reluctant to call a palliative care consultation for a patient for whom they would have otherwise called a consultation. We asked participants to identify which aspects of care they find that the palliative care team discusses most often without request from the primary gynecologic oncology team; 69% responded goals of care, 49% responded symptom control, and 33% responded code status. Most respondents (66%) felt neither upset nor relieved when palliative care team members discussed topics outside the scope of the consult. Respondents felt that palliative care providers rarely “overstepped boundaries” or were “too aggressive” to transition to end-of-life care (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Respondents’ attitudes and perceptions regarding palliative care team involvement in the care of inpatients.

DISCUSSION

We found that the overwhelming majority of respondents believe that palliative care services are a useful adjunct to patient care, yet half of respondents thought they were underused at their institutions. The main barrier identified in our survey preventing providers from consulting with palliative care specialists is the perception of the gynecologic oncologist that patients and their families will feel abandoned; access to palliative care services was not a significant barrier. A substantial proportion of respondents often or sometimes feel reluctant to consult a palliative care team.

The latest update to the ASCO guidelines for integration of palliative care into standard oncology recommends incorporating dedicated palliative care services into the care of all patients with advanced cancer early in the disease course, concurrent with life-extending therapy.10 The majority of respondents indicated that they think it is appropriate to consult palliative care at any point of the disease trajectory for assistance with pain control and other difficult symptoms. Earlier integration of specialist-level palliative care in the context of optimizing symptom management could potentially avoid the patient perception that the primary oncologist is giving up or transferring care.17 Our findings indicate that pain and symptom control could potentially serve as the impetus for early palliative care involvement.

There is ample opportunity for collaboration between gynecologic oncology and palliative care teams other than for pain and other symptom control. Gynecologic oncologists in our survey also desired palliative care provider involvement for discussion of DNR/DNI status, discussion of goals of care, and help choosing a health care proxy. In the outpatient setting, gynecologic oncologists seem to believe palliative care specialists are better communicators who can help patients navigate difficult decisions and are competent negotiators who can resolve plan-of-care conflicts with patients and family.27 Communicating prognosis was the only task that respondents clearly felt should be the sole responsibility of the primary oncologist, without involvement of the palliative care team. This noncollaborative approach seems appropriate since patients are 2.35 times more likely to understand that they have late-stage disease when this is communicated by the primary oncologist versus another care team member.28 Despite a self-perceived competence in many of the aforementioned tasks, gynecologic oncologists still desired collaboration with palliative care providers. This trend is consistent with a previous survey of SGO members, in which the majority of respondents desired a multidisciplinary team to discuss end-of-life care with the patient; however, only 15% wanted others to lead the discussion.29 Also in this survey, conducted in 2004, 77% of respondents wanted more formal training to discuss end-of-life issues. Although our survey did not specifically inquire about the desire for more formal training, the majority of respondents felt competent with end-of-life discussions, yet still desired a multidisciplinary approach to most clinical end-of-life care tasks. Gynecologic oncologists describe the care from diagnosis to death (or cure) as a unique trait of the specialty that they do not want to give up, but fellows have reported insufficient palliative care education.27,29,30 It is interesting, then, that more respondents to our survey felt more competent with discussing prognosis, code status, and goals of care than managing pain. Furthermore, they were more willing to share pain management with the palliative care team than sharing responsibility to discuss prognosis, code status, and goals of care. It is possible that the conflicting self-reported level of competency and the insufficient training reported by fellows are the result of a sense of responsibility for the patient. Are the patients being affected by later referrals to palliative care and more futile interventions?

A number of barriers to consulting palliative care in the inpatient setting related to patient and family concerns were identified by the responding gynecologic oncology providers. These include resistance from the family of involving palliative care, as well as the self-perceived concern that the family and the patient would feel that the gynecologic oncology provider is giving up and abandoning them and the patient. This finding is consistent with other studies in the literature,17,18 such as a qualitative focus group study of 28 clinicians caring for patients with lung cancer, in which perceived patient and family reaction emerged as a major barrier.16 This concern likely stems from the persistent misconceptions, of both oncologists and patients, that palliative care is not compatible with active cancer treatment and that palliative care and hospice care are synonymous.16,17,31 In a cross-sectional survey of patients with breast, lung, or GI cancers being treated in three outpatient oncology clinics at an academic medical center, the most frequently cited barriers to receiving palliative care services were the lack of physician referral and lack of knowledge of these services.32 Because the respondents to our survey did not cite access to palliative care services as a major barrier, it seems that the primary oncologist is the rate-limited factor. In the outpatient setting, gynecologic oncologists think it is a unique characteristic of the specialty to follow the patient from diagnosis to death or cure and do not like to give that up.27 Our study and others demonstrate the need for improved physician education and patient counseling regarding the benefits of palliative care.

Our study highlights many important issues with the gynecologic oncology–palliative care partnership from the gynecologic oncologists’ perspective. However, data from the perspective of palliative care providers were not obtained. These data could have been valuable for the determination of ways to improve incorporation of palliative care services into routine oncology care. Another limitation of this study was the 20% response rate, which may introduce a selection bias. It is possible that respondents who were more positively disposed to palliative care were more likely to respond; therefore, our results may reflect more favorable views than are typical for gynecologic oncologists. It is possible that physicians affiliated with an academic practice (80% of respondents) have more access to palliative care services and are more prone to use those services. However, the demographic characteristics of the study respondents are similar to the demographic characteristics of the SGO membership as published in the 2015 State of the Subspecialty Report,26 perhaps making the selection bias less of a concern. Furthermore, this response rate is not atypical for published studies of physician surveys, and this methodology is an effective approach to studying physician beliefs, behaviors, and concerns.33 Other limitations inherent in our survey study design include categorical answer choices and inability to ask follow-up questions, because the nuances of patient care and management are difficult to capture with closed-ended survey questions. Although generalizability of our results might be limited as a result of potential selection bias and response rate, we raise interesting and novel points that grant additional investigation.

We designed our survey to describe gynecologic oncologists’ needs and expectations and improve collaboration and joint patient care with palliative care providers. Our findings can help improve the documented underutilization of palliative care services and adherence to the ASCO guidelines. Respondents demonstrated interest in palliative care collaboration for pain and control of other symptoms, which can serve as the impetus for early referral to palliative care services. End-of-life discussions (eg, DNR/DNI, goals of care, health care proxy) were also identified as areas where gynecologic oncologists desire collaboration with palliative care services. Additional studies should explore the concerns of gynecologic oncologists as to whether involvement of palliative care affects patients’ feelings of abandonment or defeat. Collaborative practices on the basis of mutual trust and optimization of patient outcomes should inform the nature and extent of palliative care in gynecologic oncology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant No. R01CA16912 (J.D.W.) and NCI Diversity Supplement Grant No. CA197730 (A.I.T.). Presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology 47th Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, San Diego, CA, March 19-22, 2016.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Alexandre Buckley de Meritens, Benjamin Margolis, Ana I. Tergas

Collection and assembly of data: Alexandre Buckley de Meritens, Benjamin Margolis

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Practice Patterns, Attitudes, and Barriers to Palliative Care Consultation by Gynecologic Oncologists

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Alexandre Buckley de Meritens

No relationship to disclose

Benjamin Margolis

No relationship to disclose

Craig Blinderman

No relationship to disclose

Holly G. Prigerson

No relationship to disclose

Paul K. Maciejewski

No relationship to disclose

Megan J. Shen

No relationship to disclose

June Y. Hou

No relationship to disclose

William M. Burke

Consulting or Advisory Role: Titan Medical

Jason D. Wright

Consulting or Advisory Role: Clovis Oncology, Tesaro

Ana I. Tergas

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1. American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute : SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/

- 3. Jackson VA, Jacobsen JC, Greer J, et al: Components of early intervention outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with incurable NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 27, 2009 (suppl; abstr e20635) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302:741-749, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. : The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 164:83-91, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rugno FC, Paiva BS, Paiva CE: Early integration of palliative care facilitates the discontinuation of anticancer treatment in women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol 135:249-254, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefkowits C, Teuteberg W, Courtney-Brooks M, et al. : Improvement in symptom burden within one day after palliative care consultation in a cohort of gynecologic oncology inpatients. Gynecol Oncol 136:424-428, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrum LM, Blank S, Chen LM, et al. : Comprehensive care in gynecologic oncology: The importance of palliative care. Gynecol Oncol 137:193-202, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al: Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 35:96-112, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 30:880-887, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefkowits C, Binstock AB, Courtney-Brooks M, et al. : Predictors of palliative care consultation on an inpatient gynecologic oncology service: Are we following ASCO recommendations? Gynecol Oncol 133:319-325, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, et al. : Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 17:1574-1580, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. : Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA 303:1054-1061, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauci J, Schneider K, Walters C, et al. : The utilization of palliative care in gynecologic oncology patients near the end of life. Gynecol Oncol 127:175-179, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le BH, Mileshkin L, Doan K, et al. : Acceptability of early integration of palliative care in patients with incurable lung cancer. J Palliat Med 17:553-558, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. : Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract 10:e37-e44, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson C, Girgis A, Paul C, et al. : Australian palliative care providers’ perceptions and experiences of the barriers and facilitators to palliative care provision. Support Care Cancer 19:343-351, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward AM, Agar M, Koczwara B: Collaborating or co-existing: A survey of attitudes of medical oncologists toward specialist palliative care. Palliat Med 23:698-707, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miyashita M, Hirai K, Morita T, et al: Barriers to referral to inpatient palliative care units in Japan: A qualitative survey with content analysis. Support Care Cancer 16:217-222, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Nevadunsky NS, Spoozak L, Gordon S, et al. : End-of-life care of women with gynecologic malignancies: A pilot study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 23:546-552, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbera L, Elit L, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : End of life care for women with gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol 118:196-201, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor JS, Brown AJ, Prescott LS, et al. : Dying well: How equal is end of life care among gynecologic oncology patients? Gynecol Oncol 140:295-300, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zakhour M, LaBrant L, Rimel BJ, et al. : Too much, too late: Aggressive measures and the timing of end of life care discussions in women with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 138:383-387, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlekar M, Collier B, Parish A, et al. : Utilization and determinants of palliative care in the trauma intensive care unit: Results of a national survey. Palliat Med 28:1062-1068, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Society of Gynecologic Oncology: Gynecologic Oncology 2015: State of the Subspecialty. Chicago, IL, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, 2015.

- 27.Hay CM, Lefkowits C, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. : Gynecologic oncologist views influencing referral to outpatient specialty palliative care. Int J Gynecol Cancer 27:588-596, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cohen SM, Maciejewski RC, Nelson JE, et al: The messenger matters: Relative influence of oncologists versus other care team members on advanced cancer patients’ illness understanding. J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (supp 15; abstr 6545) [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ramondetta LM, Tortolero-Luna G, Bodurka DC, et al: Approaches for end-of-life care in the field of gynecologic oncology: An exploratory study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14:580-588, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Eskander RN, Osann K, Dickson E, et al. : Assessment of palliative care training in gynecologic oncology: A Gynecologic Oncology Fellow Research Network study. Gynecol Oncol 134:379-384, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. doi: 10.1177/0269216316648068. Thomas T, Kuhn I, Barclay S: Inpatient transfer to a care home for end-of-life care: What are the views and experiences of patients and their relatives? A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the UK literature. Palliat Med 31:102-108, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar P, Casarett D, Corcoran A, et al. : Utilization of supportive and palliative care services among oncology outpatients at one academic cancer center: Determinants of use and barriers to access. J Palliat Med 15:923-930, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellerman SE, Herold J: Physician response to surveys: A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 20:61-67, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]